User login

Agitation in children and adolescents: Diagnostic and treatment considerations

Managing agitation—verbal and/or motor restlessness that often is accompanied by irritability and a predisposition to aggression or violence—can be challenging in any patient, but particularly so in children and adolescents. In the United States, the prevalence of children and adolescents presenting to an emergency department (ED) for treatment of psychiatric symptoms, including agitation, has been on the rise.1,2

Similar to the multitude of causes of fever, agitation among children and adolescents has many possible causes.3 Because agitation can pose a risk for harm to others and/or self, it is important to manage it proactively. Other than studies that focus on agitation in pediatric anesthesia, there is a dearth of studies examining agitation and its treatment in children and adolescents. There is also a scarcity of training in the management of acute agitation in children and adolescents. In a 2017 survey of pediatric hospitalists and consultation-liaison psychiatrists at 38 academic children’s hospitals in North America, approximately 60% of respondents indicated that they had received no training in the evaluation or management of pediatric acute agitation.4 In addition, approximately 54% of participants said they did not screen for risk factors for pediatric agitation, even though 84% encountered the condition at least once a month, and as often as weekly.4

This article reviews evidence on the causes and treatments of agitation in children and adolescents. For the purposes of this review, child refers to a patient age 6 to 12, and adolescent refers to a patient age 13 to 17.

Identifying the cause

Addressing the underlying cause of agitation is essential. It’s also important to manage acute agitation while the underlying cause is being investigated in a way that does not jeopardize the patient’s emotional or physical safety.

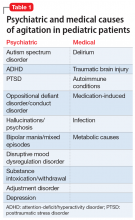

Agitation in children or teens can be due to psychiatric causes such as autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or due to medical conditions such as delirium, traumatic brain injury, or other conditions (Table 1).

In a 2005 study of 194 children with agitation in a pediatric post-anesthesia care unit, pain (27%) and anxiety (25%) were found to be the most common causes of agitation.3 Anesthesia-related agitation was a less common cause (11%). Physiologic anomalies were found to be the underlying cause of agitation in only 3 children in this study, but were undiagnosed for a prolonged period in 2 of these 3 children, which highlights the importance of a thorough differential diagnosis in the management of agitation in children.3

Assessment of an agitated child should include a comprehensive history, physical exam, and laboratory testing as indicated. When a pediatric patient comes to the ED with a chief presentation of agitation, a thorough medical and psychiatric assessment should be performed. For patients with a history of psychiatric diagnoses, do not assume that the cause of agitation is psychiatric.

Continue to: Psychiatric causes

Psychiatric causes

Autism spectrum disorder. Children and teens with autism often feel overwhelmed due to transitions, changes, and/or sensory overload. This sensory overload may be in response to relatively subtle sensory stimuli, so it may not always be apparent to parents or others around them.

Research suggests that in general, the ability to cope effectively with emotions is difficult without optimal language development. Due to cognitive/language delays and a related lack of emotional attunement and limited skills in recognizing, expressing, or coping with emotions, difficult emotions in children and adolescents with autism can manifest as agitation.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Children with ADHD may be at a higher risk for agitation, in part due to poor impulse control and limited coping skills. In addition, chronic negative feedback (from parents, teachers, or both) may contribute to low self-esteem, mood symptoms, defiance, and/or other behavioral difficulties. In addition to standard pharmacotherapy for ADHD, treatment involves parent behavior modification training. Setting firm yet empathic limits, “picking battles,” and implementing a developmentally appropriate behavioral plan to manage disruptive behavior in children or adolescents with ADHD can go a long way in helping to prevent the emergence of agitation.

Posttraumatic stress disorder. In some young children, new-onset, unexplained agitation may be the only sign of abuse or trauma. Children who have undergone trauma tend to experience confusion and distress. This may manifest as agitation or aggression, or other symptoms such as increased anxiety or nightmares.5 Trauma may be in the form of witnessing violence (domestic or other); experiencing physical, sexual, and/or emotional abuse; or witnessing/experiencing other significant threats to the safety of self and/or loved ones. Re-establishing (or establishing) a sense of psychological and physical safety is paramount in such patients.6 Psychotherapy is the first-line modality of treatment in children and adolescents with PTSD.6 In general, there is a scarcity of research on medication treatments for PTSD symptoms among children and adolescents.6

Oppositional defiant disorder/conduct disorder. Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) can be comorbid with ADHD. The diagnosis of ODD requires a pervasive pattern of anger, defiance, vindictiveness, and hostility, particularly towards authority figures. However, these symptoms need to be differentiated from the normal range of childhood behavior. Occasionally, children learn to cope maladaptively through disruptive behavior or agitation. Although a parent or caregiver may see this behavior as intentionally malevolent, in a child with limited coping skills (whether due to young age, developmental/cognitive/language/learning delays, or social communication deficits) or one who has witnessed frequent agitation or aggression in the family environment, agitation and disruptive behavior may be a maladaptive form of coping. Thus, diligence needs to be exercised in the diagnosis of ODD and in understanding the psychosocial factors affecting the child, particularly because impulsiveness and uncooperativeness on their own have been found to be linked to greater likelihood of prescription of psychotropic medications from multiple classes.7 Family-based interventions, particularly parent training, family therapy, and age-appropriate child skills training, are of prime importance in managing this condition.8 Research shows that a shortage of resources, system issues, and cultural roadblocks in implementing family-based psychosocial interventions also can contribute to the increased use of psychotropic medications for aggression in children and teens with ODD, conduct disorder, or ADHD.8 The astute clinician needs to be cognizant of this before prescribing.

Continue to: Hallucinations/psychosis

Hallucinations/psychosis. Hallucinations (whether from psychiatric or medical causes) are significantly associated with agitation.9 In particular, auditory command hallucinations have been linked to agitation. Command hallucinations in children and adolescents may be secondary to early-onset schizophrenia; however, this diagnosis is rare.10 Hallucinations can also be an adverse effect of amphetamine-based stimulant medications in children and adolescents. Visual hallucinations are most often a sign of an underlying medical disorder such as delirium, occipital lobe mass/infection, or drug intoxication or withdrawal. Hallucinations need to be distinguished from the normal, imaginative play of a young child.10

Bipolar mania. In adults, bipolar disorder is a primary psychiatric cause of agitation. In children and adolescents, the diagnosis of bipolar disorder can be complex and requires careful and nuanced history-taking. The risks of agitation are greater with bipolar disorder than with unipolar depression.11,12

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Prior to DSM-5, many children and adolescents with chronic, non-episodic irritability and severe outbursts out of proportion to the situation or stimuli were given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. These symptoms, in combination with other symptoms, are now considered part of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder when severe outbursts in a child or adolescent occur 3 to 4 times a week consistently, for at least 1 year. The diagnosis of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder requires ruling out other psychiatric and medical conditions, particularly ADHD.13

Substance intoxication/withdrawal. Intoxication or withdrawal from substances such as alcohol, stimulant medications, opioids, methamphetamines, and other agents can lead to agitation. This is more likely to occur among adolescents than children.14

Adjustment disorder. Parental divorce, especially if it is conflictual, or other life stressors, such as experiencing a move or frequent moves, may contribute to the development of agitation in children and adolescents.

Continue to: Depression

Depression. In children and adolescents, depression can manifest as anger or irritability, and occasionally as agitation.

Medical causes

Delirium. Refractory agitation is often a manifestation of delirium in children and adolescents.15 If unrecognized and untreated, delirium can be fatal.16 Therefore, it is imperative that clinicians routinely assess for delirium in any patient who presents with agitation.

Because a patient with delirium often presents with agitation and visual or auditory hallucinations, the medical team may tend to assume these symptoms are secondary to a psychiatric disorder. In this case, the role of the consultation-liaison psychiatrist is critical for guiding the medical team, particularly to continue a thorough exploration of underlying causes while avoiding polypharmacy. Noise, bright lights, frequent changes in nursing staff or caregivers, anticholinergic or benzodiazepine medications, and frequent changes in schedules should be avoided to prevent delirium from occurring or getting worse.17 A multidisciplinary team approach is key in identifying the underlying cause and managing delirium in pediatric patients.

Traumatic brain injury. Agitation may be a presenting symptom in youth with traumatic brain injury (TBI).18 Agitation may present often in the acute recovery phase.19 There is limited evidence on the efficacy and safety of pharmacotherapy for agitation in pediatric patients with TBI.18

Autoimmune conditions. In a study of 27 patients with

Continue to: Medication-induced/iatrogenic

Medication-induced/iatrogenic. Agitation can be an adverse effect of medications such as amantadine (often used for TBI),18 atypical antipsychotics,21 selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

Infection. Agitation can be a result of encephalitis, meningitis, or other infectious processes.22

Metabolic conditions. Hepatic or renal failure, diabetic ketoacidosis, and thyroid toxicosis may cause agitation in children or adolescents.22

Start with nonpharmacologic interventions

Few studies have examined de-escalation techniques in agitated children and adolescents. However, verbal de-escalation is generally viewed as the first-line technique for managing agitation in children and adolescents. When feasible, teaching and modeling developmentally appropriate stress management skills for children and teens can be a beneficial preventative strategy to reduce the incidence and worsening of agitation.23

Clinicians should refrain from using coercion.24 Coercion could harm the therapeutic alliance, thereby impeding assessment of the underlying causes of agitation, and can be particularly harmful for patients who have a history of trauma or abuse. Even in pediatric patients with no such history, coercion is discouraged due to its punitive connotations and potential to adversely impact a vulnerable child or teen.

Continue to: Establishing a therapeutic rapport...

Establishing a therapeutic rapport with the patient, when feasible, can facilitate smoother de-escalation by offering the patient an outlet to air his/her frustrations and emotions, and by helping the patient feel understood.24 To facilitate this, ensure that the patient’s basic comforts and needs are met, such as access to a warm bed, food, and safety.25

The psychiatrist’s role is to help uncover and address the underlying reason for the patient’s agony or distress. Once the child or adolescent has calmed, explore potential triggers or causes of the agitation.

There has been a significant move away from the use of restraints for managing agitation in children and adolescents.26 Restraints have a psychologically traumatizing effect,27 and have been linked to life-threatening injuries and death in children.24

Pharmacotherapy: Proceed with caution

There are no FDA-approved medications for the treatment of agitation in the general pediatric population, and any medication use in this population is off-label. There is also a dearth of research examining the safety and efficacy of using psychotropic medications for agitation in pediatric patients. Because children and adolescents are more susceptible to adverse effects and risks associated with the use of psychotropic medications, special caution is warranted. In general, pharmacologic interventions are not recommended without the use of psychotherapy-based modalities.

In the past, the aim of using medications to treat patients with agitation was to put the patient to sleep.25 This practice did not help clinicians to assess for underlying causes, and was often accompanied by a greater risk of adverse effects and reactions.24 Therefore, the goal of medication treatment for agitation is to help calm the patient instead of inducing sleep.25

Continue to: Pharmacotherapy should...

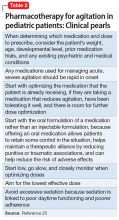

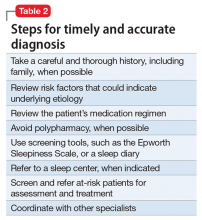

Pharmacotherapy should be used only when behavioral interventions have been unsuccessful. Key considerations for using psychotropic medications to address agitation in children and adolescents are summarized in Table 2.25

Antipsychotics, particularly second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), have been commonly used to manage acute agitation in children and adolescents, and there has been an upswing in the use of these medications in the United States in the last several years.28 Research indicates that males, children and adolescents in foster care, and those with Medicaid have been the more frequent youth recipients of SGAs.29 Of particular concern is the prevalence of antipsychotic use among children younger than age 6. In the last few decades, there has been an increase in the prescription of antipsychotics for children younger than age 6, particularly for disruptive behavior and aggression.30 In a study of preschool-age Medicaid patients in Kentucky, 70,777 prescriptions for SGAs were given to 6,915 children <6 years of age; 73% of these prescriptions were for male patients.30 Because there is a lack of controlled studies examining the safety and efficacy of SGAs among children and adolescents, especially with long-term use, further research is needed and caution is warranted.28

The FDA has approved

Externalizing disorders among children and adolescents tend to get treated with antipsychotics.28 A Canadian study examining records of 6,916 children found that most children who had been prescribed risperidone received it for ADHD or conduct disorder, and most patients had not received laboratory testing for monitoring the antipsychotic medication they were taking.31 In a 2018 study examining medical records of 120 pediatric patients who presented to an ED in British Columbia with agitation, antipsychotics were the most commonly used medications for patients with autism spectrum disorder; most patients received at least 1 dose.14

For children and adolescents with agitation or aggression who were admitted to inpatient units, IM

Continue to: In case reports...

In case reports, a combination of olanzapine with CNS-suppressing agents has resulted in death. Therefore, do not combine olanzapine with agents such as benzodiazepines.25 In a patient with a likely medical source of agitation, insufficient evidence exists to support the use of olanzapine, and additional research is needed.25

Low-dose haloperidol has been found to be effective for delirium-related agitation in pediatric studies.15 Before initiating an antipsychotic for any child or adolescent, review the patient’s family history for reports of early cardiac death and the patient’s own history of cardiac symptoms, palpitations, syncope, or prolonged QT interval. Monitor for QT prolongation. Among commonly used antipsychotics, the risk of QT prolongation is higher with IV administration of haloperidol and with ziprasidone. Studies show that compared with oral or IM

A few studies have found risperidone to be efficacious for treating ODD and conduct disorder; however, this use is off-label, and its considerable adverse effect and risk profile needs to be weighed against the potential benefit.8

Antipsychotic polypharmacy should be avoided because of the higher risk of adverse effects and interactions, and a lack of robust, controlled studies evaluating the safety of using antipsychotics for non-FDA-approved indications in children and adolescents.7 All patients who receive antipsychotics require monitoring for extrapyramidal symptoms, tardive dyskinesia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, orthostatic hypotension, sedation, metabolic syndrome, and other potential adverse effects. Patients receiving risperidone need to have their prolactin levels monitored periodically, and their parents should be made aware of the potential for hyperprolactinemia and other adverse effects. Aripiprazole and quetiapine may increase the risk of suicidality.

Antiepileptics. A meta-analysis of 7 randomized controlled trials examining the use of antiepileptic medications (

Continue to: In a retrospective case series...

In a retrospective case series of 30 pediatric patients with autism spectrum disorder who were given oxcarbazepine, Douglas et al35 found that 47% of participants experienced significant improvement in irritability/agitation. However, 23% of patients reported significant adverse effects leading to discontinuation. Insufficient evidence exists for the safety and efficacy of oxcarbazepine in this population.35

Benzodiazepines. The use of benzodiazepines in pediatric patients has been associated with paradoxical disinhibition reactions, particularly in children with autism and other developmental or cognitive disabilities or delays.21 There is a lack of data on the safety and efficacy of long-term use of benzodiazepines in children, especially in light of these patients’ developing brains, the risk of cognitive impairment, and the potential for dependence with long-term use. Despite this, some studies show that the use of benzodiazepines is fairly common among pediatric patients who present to the ED with agitation.14 In a recent retrospective study, Kendrick et al14 found that among pediatric patients with agitation who were brought to the ED, benzodiazepines were the most commonly prescribed medications.

Other medications. Clonidine and

Diphenhydramine, in both oral and IM forms, has been used to treat agitation in children,32 but has also been associated with a paradoxical disinhibition reaction in pediatric patients21 and therefore should be used only sparingly and with caution. Diphenhydramine has anticholinergic properties, and may worsen delirium.15 Stimulant medications can help aggressive behavior in children and adolescents with ADHD.37

Bottom Line

Agitation among children and adolescents has many possible causes. A combination of a comprehensive assessment and evidence-based, judicious treatment interventions can help prevent and manage agitation in this vulnerable population.

Related Resources

- Baker M, Carlson GA. What do we really know about PRN use in agitated children with mental health conditions: a clinical review. Evid Based Ment Health. 2018;21(4):166-170.

- Gerson R, Malas N, Mroczkowski MM. Crisis in the emergency department: the evaluation and management of acute agitation in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2018;27(3):367-386.

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Symmetrel

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Clonidine • Catapres

Guanfacine • Intuniv, Tenex

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Levetiracetam • Keppra, Spritam

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Oxcarbazepine • Trileptal

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Topiramate • Topamax

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valproate • Depakene

Ziprasidone • Geodon

1. Frosch E, Kelly P. Issues in pediatric psychiatric emergency care. In: Emergency psychiatry. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2011:185-199.

2. American College of Emergency Physicians. Pediatric mental health emergencies in the emergency department. https://www.acep.org/patient-care/policy-statements/pediatric-mental-health-emergencies-in-the-emergency-medical-services-system/. Revised September 2018. Accessed February 23, 2019.

3. Voepel-Lewis, T, Burke C, Hadden S, et al. Nurses’ diagnoses and treatment decisions regarding care of the agitated child. J Perianesth Nurs. 2005;20(4):239-248.

4. Malas N, Spital L, Fischer J, et al. National survey on pediatric acute agitation and behavioral escalation in academic inpatient pediatric care settings. Psychosomatics. 2017;58(3):299-306.

5. Famularo R, Kinscherff R, Fenton T. Symptom differences in acute and chronic presentation of childhood post-traumatic stress disorder. Child Abuse Negl. 1990;14(3):439-444.

6. Kaminer D, Seedat S, Stein DJ. Post-traumatic stress disorder in children. World Psychiatry. 2005;4(2):121-125.

7. Ninan A, Stewart SL, Theall LA, et al. Adverse effects of psychotropic medications in children: predictive factors. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23(3):218-225.

8. Pringsheim T, Hirsch L, Gardner D, et al. The pharmacological management of oppositional behaviour, conduct problems, and aggression in children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Part 2: antipsychotics and traditional mood stabilizers. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(2):52-61.

9. Vareilles D, Bréhin C, Cortey C, et al. Hallucinations: Etiological analysis of children admitted to a pediatric emergency department. Arch Pediatr. 2017;24(5):445-452.

10. Bartlett J. Childhood-onset schizophrenia: what do we really know? Health Psychol Behav Med. 2014;2(1):735-747.

11. Diler RS, Goldstein TR, Hafeman D, et al. Distinguishing bipolar depression from unipolar depression in youth: Preliminary findings. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(4):310-319.

12. Dervic K, Garcia-Amador M, Sudol K, et al. Bipolar I and II versus unipolar depression: clinical differences and impulsivity/aggression traits. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(1):106-113.

13. Masi L, Gignac M ADHD and DMDD comorbidities, similarities and distinctions. J Child Adolesc Behav2016;4:325.

14. Kendrick JG, Goldman RD, Carr RR. Pharmacologic management of agitation and aggression in a pediatric emergency department - a retrospective cohort study. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2018;23(6):455-459.

15. Schieveld JN, Staal M, Voogd L, et al. Refractory agitation as a marker for pediatric delirium in very young infants at a pediatric intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(11):1982-1983.

16. Traube C, Silver G, Gerber LM, et al. Delirium and mortality in critically ill children: epidemiology and outcomes of pediatric delirium. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(5):891-898.

17. Bettencourt A, Mullen JE. Delirium in children: identification, prevention, and management. Crit Care Nurse. 2017;37(3):e9-e18.

18. Suskauer SJ, Trovato MK. Update on pharmaceutical intervention for disorders of consciousness and agitation after traumatic brain injury in children. PM R. 2013;5(2):142-147.

19. Nowicki M, Pearlman L, Campbell C, et al. Agitated behavior scale in pediatric traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2019. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2019.1565893.

20. Mohammad SS, Jones H, Hong M, et al. Symptomatic treatment of children with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58(4):376-384.

21. Sonnier L, Barzman D. Pharmacologic management of acutely agitated pediatric patients. Pediatr Drugs. 2011;13(1):1-10.

22. Nordstrom K, Zun LS, Wilson MP, et al. Medical evaluation and triage of the agitated patient: consensus statement of the american association for emergency psychiatry project Beta medical evaluation workgroup. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13(1):3-10.

23. Masters KJ, Bellonci C, Bernet W, et al; American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameter for the prevention and management of aggressive behavior in child and adolescent psychiatric institutions, with special reference to seclusion and restraint. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(2 suppl):4S-25S.

24. Croce ND, Mantovani C. Using de-escalation techniques to prevent violent behavior in pediatric psychiatric emergencies: It is possible. Pediatric Dimensions, 2017;2(1):1-2.

25. Marzullo LR. Pharmacologic management of the agitated child. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(4):269-275.

26. Caldwell B, Albert C, Azeem MW, et al. Successful seclusion and restraint prevention effort in child and adolescent programs. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2014;52(11):30-38.

27. De Hert M, Dirix N, Demunter H, et al. Prevalence and correlates of seclusion and restraint use in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20(5):221-230.

28. Crystal S, Olfson M, Huang C, et al. Broadened use of atypical antipsychotics: safety, effectiveness, and policy challenges. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(5):w770-w781.

29. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the use of atypical antipsychotic medication in children and adolescents. https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/docs/practice_parameters/Atypical_Antipsychotic_Medications_Web.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2019.

30. Lohr WD, Chowning RT, Stevenson MD, et al. Trends in atypical antipsychotics prescribed to children six years of age or less on Medicaid in Kentucky. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2015;25(5):440-443.

31. Chen W, Cepoiu-Martin M, Stang A, et al. Antipsychotic prescribing and safety monitoring practices in children and youth: a population-based study in Alberta, Canada. Clin Drug Investig. 2018;38(5):449-455.

32. Deshmukh P, Kulkarni G, Barzman D. Recommendations for pharmacological management of inpatient aggression in children and adolescents. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2010;7(2):32-40.

33. Haldol [package insert]. Beerse, Belgium: Janssen Pharmaceutica NV; 2005.

34. Hirota T, Veenstra-Vanderweele J, Hollander E, et al. Antiepileptic medications in autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(4):948-957.

35. Douglas JF, Sanders KB, Benneyworth MH, et al. Brief report: retrospective case series of oxcarbazepine for irritability/agitation symptoms in autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(5):1243-1247.

36. Harmon RJ, Riggs PD. Clonidine for posttraumatic stress disorder in preschool children. J Am Acad

37. Pringsheim T, Hirsch L, Gardner D, et al. The pharmacological management of oppositional behaviour, conduct problems, and aggression in children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Part 1: Psychostimulants, alpha-2 Agonists, and atomoxetine. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(2):42-51

Managing agitation—verbal and/or motor restlessness that often is accompanied by irritability and a predisposition to aggression or violence—can be challenging in any patient, but particularly so in children and adolescents. In the United States, the prevalence of children and adolescents presenting to an emergency department (ED) for treatment of psychiatric symptoms, including agitation, has been on the rise.1,2

Similar to the multitude of causes of fever, agitation among children and adolescents has many possible causes.3 Because agitation can pose a risk for harm to others and/or self, it is important to manage it proactively. Other than studies that focus on agitation in pediatric anesthesia, there is a dearth of studies examining agitation and its treatment in children and adolescents. There is also a scarcity of training in the management of acute agitation in children and adolescents. In a 2017 survey of pediatric hospitalists and consultation-liaison psychiatrists at 38 academic children’s hospitals in North America, approximately 60% of respondents indicated that they had received no training in the evaluation or management of pediatric acute agitation.4 In addition, approximately 54% of participants said they did not screen for risk factors for pediatric agitation, even though 84% encountered the condition at least once a month, and as often as weekly.4

This article reviews evidence on the causes and treatments of agitation in children and adolescents. For the purposes of this review, child refers to a patient age 6 to 12, and adolescent refers to a patient age 13 to 17.

Identifying the cause

Addressing the underlying cause of agitation is essential. It’s also important to manage acute agitation while the underlying cause is being investigated in a way that does not jeopardize the patient’s emotional or physical safety.

Agitation in children or teens can be due to psychiatric causes such as autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or due to medical conditions such as delirium, traumatic brain injury, or other conditions (Table 1).

In a 2005 study of 194 children with agitation in a pediatric post-anesthesia care unit, pain (27%) and anxiety (25%) were found to be the most common causes of agitation.3 Anesthesia-related agitation was a less common cause (11%). Physiologic anomalies were found to be the underlying cause of agitation in only 3 children in this study, but were undiagnosed for a prolonged period in 2 of these 3 children, which highlights the importance of a thorough differential diagnosis in the management of agitation in children.3

Assessment of an agitated child should include a comprehensive history, physical exam, and laboratory testing as indicated. When a pediatric patient comes to the ED with a chief presentation of agitation, a thorough medical and psychiatric assessment should be performed. For patients with a history of psychiatric diagnoses, do not assume that the cause of agitation is psychiatric.

Continue to: Psychiatric causes

Psychiatric causes

Autism spectrum disorder. Children and teens with autism often feel overwhelmed due to transitions, changes, and/or sensory overload. This sensory overload may be in response to relatively subtle sensory stimuli, so it may not always be apparent to parents or others around them.

Research suggests that in general, the ability to cope effectively with emotions is difficult without optimal language development. Due to cognitive/language delays and a related lack of emotional attunement and limited skills in recognizing, expressing, or coping with emotions, difficult emotions in children and adolescents with autism can manifest as agitation.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Children with ADHD may be at a higher risk for agitation, in part due to poor impulse control and limited coping skills. In addition, chronic negative feedback (from parents, teachers, or both) may contribute to low self-esteem, mood symptoms, defiance, and/or other behavioral difficulties. In addition to standard pharmacotherapy for ADHD, treatment involves parent behavior modification training. Setting firm yet empathic limits, “picking battles,” and implementing a developmentally appropriate behavioral plan to manage disruptive behavior in children or adolescents with ADHD can go a long way in helping to prevent the emergence of agitation.

Posttraumatic stress disorder. In some young children, new-onset, unexplained agitation may be the only sign of abuse or trauma. Children who have undergone trauma tend to experience confusion and distress. This may manifest as agitation or aggression, or other symptoms such as increased anxiety or nightmares.5 Trauma may be in the form of witnessing violence (domestic or other); experiencing physical, sexual, and/or emotional abuse; or witnessing/experiencing other significant threats to the safety of self and/or loved ones. Re-establishing (or establishing) a sense of psychological and physical safety is paramount in such patients.6 Psychotherapy is the first-line modality of treatment in children and adolescents with PTSD.6 In general, there is a scarcity of research on medication treatments for PTSD symptoms among children and adolescents.6

Oppositional defiant disorder/conduct disorder. Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) can be comorbid with ADHD. The diagnosis of ODD requires a pervasive pattern of anger, defiance, vindictiveness, and hostility, particularly towards authority figures. However, these symptoms need to be differentiated from the normal range of childhood behavior. Occasionally, children learn to cope maladaptively through disruptive behavior or agitation. Although a parent or caregiver may see this behavior as intentionally malevolent, in a child with limited coping skills (whether due to young age, developmental/cognitive/language/learning delays, or social communication deficits) or one who has witnessed frequent agitation or aggression in the family environment, agitation and disruptive behavior may be a maladaptive form of coping. Thus, diligence needs to be exercised in the diagnosis of ODD and in understanding the psychosocial factors affecting the child, particularly because impulsiveness and uncooperativeness on their own have been found to be linked to greater likelihood of prescription of psychotropic medications from multiple classes.7 Family-based interventions, particularly parent training, family therapy, and age-appropriate child skills training, are of prime importance in managing this condition.8 Research shows that a shortage of resources, system issues, and cultural roadblocks in implementing family-based psychosocial interventions also can contribute to the increased use of psychotropic medications for aggression in children and teens with ODD, conduct disorder, or ADHD.8 The astute clinician needs to be cognizant of this before prescribing.

Continue to: Hallucinations/psychosis

Hallucinations/psychosis. Hallucinations (whether from psychiatric or medical causes) are significantly associated with agitation.9 In particular, auditory command hallucinations have been linked to agitation. Command hallucinations in children and adolescents may be secondary to early-onset schizophrenia; however, this diagnosis is rare.10 Hallucinations can also be an adverse effect of amphetamine-based stimulant medications in children and adolescents. Visual hallucinations are most often a sign of an underlying medical disorder such as delirium, occipital lobe mass/infection, or drug intoxication or withdrawal. Hallucinations need to be distinguished from the normal, imaginative play of a young child.10

Bipolar mania. In adults, bipolar disorder is a primary psychiatric cause of agitation. In children and adolescents, the diagnosis of bipolar disorder can be complex and requires careful and nuanced history-taking. The risks of agitation are greater with bipolar disorder than with unipolar depression.11,12

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Prior to DSM-5, many children and adolescents with chronic, non-episodic irritability and severe outbursts out of proportion to the situation or stimuli were given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. These symptoms, in combination with other symptoms, are now considered part of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder when severe outbursts in a child or adolescent occur 3 to 4 times a week consistently, for at least 1 year. The diagnosis of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder requires ruling out other psychiatric and medical conditions, particularly ADHD.13

Substance intoxication/withdrawal. Intoxication or withdrawal from substances such as alcohol, stimulant medications, opioids, methamphetamines, and other agents can lead to agitation. This is more likely to occur among adolescents than children.14

Adjustment disorder. Parental divorce, especially if it is conflictual, or other life stressors, such as experiencing a move or frequent moves, may contribute to the development of agitation in children and adolescents.

Continue to: Depression

Depression. In children and adolescents, depression can manifest as anger or irritability, and occasionally as agitation.

Medical causes

Delirium. Refractory agitation is often a manifestation of delirium in children and adolescents.15 If unrecognized and untreated, delirium can be fatal.16 Therefore, it is imperative that clinicians routinely assess for delirium in any patient who presents with agitation.

Because a patient with delirium often presents with agitation and visual or auditory hallucinations, the medical team may tend to assume these symptoms are secondary to a psychiatric disorder. In this case, the role of the consultation-liaison psychiatrist is critical for guiding the medical team, particularly to continue a thorough exploration of underlying causes while avoiding polypharmacy. Noise, bright lights, frequent changes in nursing staff or caregivers, anticholinergic or benzodiazepine medications, and frequent changes in schedules should be avoided to prevent delirium from occurring or getting worse.17 A multidisciplinary team approach is key in identifying the underlying cause and managing delirium in pediatric patients.

Traumatic brain injury. Agitation may be a presenting symptom in youth with traumatic brain injury (TBI).18 Agitation may present often in the acute recovery phase.19 There is limited evidence on the efficacy and safety of pharmacotherapy for agitation in pediatric patients with TBI.18

Autoimmune conditions. In a study of 27 patients with

Continue to: Medication-induced/iatrogenic

Medication-induced/iatrogenic. Agitation can be an adverse effect of medications such as amantadine (often used for TBI),18 atypical antipsychotics,21 selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

Infection. Agitation can be a result of encephalitis, meningitis, or other infectious processes.22

Metabolic conditions. Hepatic or renal failure, diabetic ketoacidosis, and thyroid toxicosis may cause agitation in children or adolescents.22

Start with nonpharmacologic interventions

Few studies have examined de-escalation techniques in agitated children and adolescents. However, verbal de-escalation is generally viewed as the first-line technique for managing agitation in children and adolescents. When feasible, teaching and modeling developmentally appropriate stress management skills for children and teens can be a beneficial preventative strategy to reduce the incidence and worsening of agitation.23

Clinicians should refrain from using coercion.24 Coercion could harm the therapeutic alliance, thereby impeding assessment of the underlying causes of agitation, and can be particularly harmful for patients who have a history of trauma or abuse. Even in pediatric patients with no such history, coercion is discouraged due to its punitive connotations and potential to adversely impact a vulnerable child or teen.

Continue to: Establishing a therapeutic rapport...

Establishing a therapeutic rapport with the patient, when feasible, can facilitate smoother de-escalation by offering the patient an outlet to air his/her frustrations and emotions, and by helping the patient feel understood.24 To facilitate this, ensure that the patient’s basic comforts and needs are met, such as access to a warm bed, food, and safety.25

The psychiatrist’s role is to help uncover and address the underlying reason for the patient’s agony or distress. Once the child or adolescent has calmed, explore potential triggers or causes of the agitation.

There has been a significant move away from the use of restraints for managing agitation in children and adolescents.26 Restraints have a psychologically traumatizing effect,27 and have been linked to life-threatening injuries and death in children.24

Pharmacotherapy: Proceed with caution

There are no FDA-approved medications for the treatment of agitation in the general pediatric population, and any medication use in this population is off-label. There is also a dearth of research examining the safety and efficacy of using psychotropic medications for agitation in pediatric patients. Because children and adolescents are more susceptible to adverse effects and risks associated with the use of psychotropic medications, special caution is warranted. In general, pharmacologic interventions are not recommended without the use of psychotherapy-based modalities.

In the past, the aim of using medications to treat patients with agitation was to put the patient to sleep.25 This practice did not help clinicians to assess for underlying causes, and was often accompanied by a greater risk of adverse effects and reactions.24 Therefore, the goal of medication treatment for agitation is to help calm the patient instead of inducing sleep.25

Continue to: Pharmacotherapy should...

Pharmacotherapy should be used only when behavioral interventions have been unsuccessful. Key considerations for using psychotropic medications to address agitation in children and adolescents are summarized in Table 2.25

Antipsychotics, particularly second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), have been commonly used to manage acute agitation in children and adolescents, and there has been an upswing in the use of these medications in the United States in the last several years.28 Research indicates that males, children and adolescents in foster care, and those with Medicaid have been the more frequent youth recipients of SGAs.29 Of particular concern is the prevalence of antipsychotic use among children younger than age 6. In the last few decades, there has been an increase in the prescription of antipsychotics for children younger than age 6, particularly for disruptive behavior and aggression.30 In a study of preschool-age Medicaid patients in Kentucky, 70,777 prescriptions for SGAs were given to 6,915 children <6 years of age; 73% of these prescriptions were for male patients.30 Because there is a lack of controlled studies examining the safety and efficacy of SGAs among children and adolescents, especially with long-term use, further research is needed and caution is warranted.28

The FDA has approved

Externalizing disorders among children and adolescents tend to get treated with antipsychotics.28 A Canadian study examining records of 6,916 children found that most children who had been prescribed risperidone received it for ADHD or conduct disorder, and most patients had not received laboratory testing for monitoring the antipsychotic medication they were taking.31 In a 2018 study examining medical records of 120 pediatric patients who presented to an ED in British Columbia with agitation, antipsychotics were the most commonly used medications for patients with autism spectrum disorder; most patients received at least 1 dose.14

For children and adolescents with agitation or aggression who were admitted to inpatient units, IM

Continue to: In case reports...

In case reports, a combination of olanzapine with CNS-suppressing agents has resulted in death. Therefore, do not combine olanzapine with agents such as benzodiazepines.25 In a patient with a likely medical source of agitation, insufficient evidence exists to support the use of olanzapine, and additional research is needed.25

Low-dose haloperidol has been found to be effective for delirium-related agitation in pediatric studies.15 Before initiating an antipsychotic for any child or adolescent, review the patient’s family history for reports of early cardiac death and the patient’s own history of cardiac symptoms, palpitations, syncope, or prolonged QT interval. Monitor for QT prolongation. Among commonly used antipsychotics, the risk of QT prolongation is higher with IV administration of haloperidol and with ziprasidone. Studies show that compared with oral or IM

A few studies have found risperidone to be efficacious for treating ODD and conduct disorder; however, this use is off-label, and its considerable adverse effect and risk profile needs to be weighed against the potential benefit.8

Antipsychotic polypharmacy should be avoided because of the higher risk of adverse effects and interactions, and a lack of robust, controlled studies evaluating the safety of using antipsychotics for non-FDA-approved indications in children and adolescents.7 All patients who receive antipsychotics require monitoring for extrapyramidal symptoms, tardive dyskinesia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, orthostatic hypotension, sedation, metabolic syndrome, and other potential adverse effects. Patients receiving risperidone need to have their prolactin levels monitored periodically, and their parents should be made aware of the potential for hyperprolactinemia and other adverse effects. Aripiprazole and quetiapine may increase the risk of suicidality.

Antiepileptics. A meta-analysis of 7 randomized controlled trials examining the use of antiepileptic medications (

Continue to: In a retrospective case series...

In a retrospective case series of 30 pediatric patients with autism spectrum disorder who were given oxcarbazepine, Douglas et al35 found that 47% of participants experienced significant improvement in irritability/agitation. However, 23% of patients reported significant adverse effects leading to discontinuation. Insufficient evidence exists for the safety and efficacy of oxcarbazepine in this population.35

Benzodiazepines. The use of benzodiazepines in pediatric patients has been associated with paradoxical disinhibition reactions, particularly in children with autism and other developmental or cognitive disabilities or delays.21 There is a lack of data on the safety and efficacy of long-term use of benzodiazepines in children, especially in light of these patients’ developing brains, the risk of cognitive impairment, and the potential for dependence with long-term use. Despite this, some studies show that the use of benzodiazepines is fairly common among pediatric patients who present to the ED with agitation.14 In a recent retrospective study, Kendrick et al14 found that among pediatric patients with agitation who were brought to the ED, benzodiazepines were the most commonly prescribed medications.

Other medications. Clonidine and

Diphenhydramine, in both oral and IM forms, has been used to treat agitation in children,32 but has also been associated with a paradoxical disinhibition reaction in pediatric patients21 and therefore should be used only sparingly and with caution. Diphenhydramine has anticholinergic properties, and may worsen delirium.15 Stimulant medications can help aggressive behavior in children and adolescents with ADHD.37

Bottom Line

Agitation among children and adolescents has many possible causes. A combination of a comprehensive assessment and evidence-based, judicious treatment interventions can help prevent and manage agitation in this vulnerable population.

Related Resources

- Baker M, Carlson GA. What do we really know about PRN use in agitated children with mental health conditions: a clinical review. Evid Based Ment Health. 2018;21(4):166-170.

- Gerson R, Malas N, Mroczkowski MM. Crisis in the emergency department: the evaluation and management of acute agitation in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2018;27(3):367-386.

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Symmetrel

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Clonidine • Catapres

Guanfacine • Intuniv, Tenex

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Levetiracetam • Keppra, Spritam

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Oxcarbazepine • Trileptal

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Topiramate • Topamax

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valproate • Depakene

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Managing agitation—verbal and/or motor restlessness that often is accompanied by irritability and a predisposition to aggression or violence—can be challenging in any patient, but particularly so in children and adolescents. In the United States, the prevalence of children and adolescents presenting to an emergency department (ED) for treatment of psychiatric symptoms, including agitation, has been on the rise.1,2

Similar to the multitude of causes of fever, agitation among children and adolescents has many possible causes.3 Because agitation can pose a risk for harm to others and/or self, it is important to manage it proactively. Other than studies that focus on agitation in pediatric anesthesia, there is a dearth of studies examining agitation and its treatment in children and adolescents. There is also a scarcity of training in the management of acute agitation in children and adolescents. In a 2017 survey of pediatric hospitalists and consultation-liaison psychiatrists at 38 academic children’s hospitals in North America, approximately 60% of respondents indicated that they had received no training in the evaluation or management of pediatric acute agitation.4 In addition, approximately 54% of participants said they did not screen for risk factors for pediatric agitation, even though 84% encountered the condition at least once a month, and as often as weekly.4

This article reviews evidence on the causes and treatments of agitation in children and adolescents. For the purposes of this review, child refers to a patient age 6 to 12, and adolescent refers to a patient age 13 to 17.

Identifying the cause

Addressing the underlying cause of agitation is essential. It’s also important to manage acute agitation while the underlying cause is being investigated in a way that does not jeopardize the patient’s emotional or physical safety.

Agitation in children or teens can be due to psychiatric causes such as autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or due to medical conditions such as delirium, traumatic brain injury, or other conditions (Table 1).

In a 2005 study of 194 children with agitation in a pediatric post-anesthesia care unit, pain (27%) and anxiety (25%) were found to be the most common causes of agitation.3 Anesthesia-related agitation was a less common cause (11%). Physiologic anomalies were found to be the underlying cause of agitation in only 3 children in this study, but were undiagnosed for a prolonged period in 2 of these 3 children, which highlights the importance of a thorough differential diagnosis in the management of agitation in children.3

Assessment of an agitated child should include a comprehensive history, physical exam, and laboratory testing as indicated. When a pediatric patient comes to the ED with a chief presentation of agitation, a thorough medical and psychiatric assessment should be performed. For patients with a history of psychiatric diagnoses, do not assume that the cause of agitation is psychiatric.

Continue to: Psychiatric causes

Psychiatric causes

Autism spectrum disorder. Children and teens with autism often feel overwhelmed due to transitions, changes, and/or sensory overload. This sensory overload may be in response to relatively subtle sensory stimuli, so it may not always be apparent to parents or others around them.

Research suggests that in general, the ability to cope effectively with emotions is difficult without optimal language development. Due to cognitive/language delays and a related lack of emotional attunement and limited skills in recognizing, expressing, or coping with emotions, difficult emotions in children and adolescents with autism can manifest as agitation.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Children with ADHD may be at a higher risk for agitation, in part due to poor impulse control and limited coping skills. In addition, chronic negative feedback (from parents, teachers, or both) may contribute to low self-esteem, mood symptoms, defiance, and/or other behavioral difficulties. In addition to standard pharmacotherapy for ADHD, treatment involves parent behavior modification training. Setting firm yet empathic limits, “picking battles,” and implementing a developmentally appropriate behavioral plan to manage disruptive behavior in children or adolescents with ADHD can go a long way in helping to prevent the emergence of agitation.

Posttraumatic stress disorder. In some young children, new-onset, unexplained agitation may be the only sign of abuse or trauma. Children who have undergone trauma tend to experience confusion and distress. This may manifest as agitation or aggression, or other symptoms such as increased anxiety or nightmares.5 Trauma may be in the form of witnessing violence (domestic or other); experiencing physical, sexual, and/or emotional abuse; or witnessing/experiencing other significant threats to the safety of self and/or loved ones. Re-establishing (or establishing) a sense of psychological and physical safety is paramount in such patients.6 Psychotherapy is the first-line modality of treatment in children and adolescents with PTSD.6 In general, there is a scarcity of research on medication treatments for PTSD symptoms among children and adolescents.6

Oppositional defiant disorder/conduct disorder. Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) can be comorbid with ADHD. The diagnosis of ODD requires a pervasive pattern of anger, defiance, vindictiveness, and hostility, particularly towards authority figures. However, these symptoms need to be differentiated from the normal range of childhood behavior. Occasionally, children learn to cope maladaptively through disruptive behavior or agitation. Although a parent or caregiver may see this behavior as intentionally malevolent, in a child with limited coping skills (whether due to young age, developmental/cognitive/language/learning delays, or social communication deficits) or one who has witnessed frequent agitation or aggression in the family environment, agitation and disruptive behavior may be a maladaptive form of coping. Thus, diligence needs to be exercised in the diagnosis of ODD and in understanding the psychosocial factors affecting the child, particularly because impulsiveness and uncooperativeness on their own have been found to be linked to greater likelihood of prescription of psychotropic medications from multiple classes.7 Family-based interventions, particularly parent training, family therapy, and age-appropriate child skills training, are of prime importance in managing this condition.8 Research shows that a shortage of resources, system issues, and cultural roadblocks in implementing family-based psychosocial interventions also can contribute to the increased use of psychotropic medications for aggression in children and teens with ODD, conduct disorder, or ADHD.8 The astute clinician needs to be cognizant of this before prescribing.

Continue to: Hallucinations/psychosis

Hallucinations/psychosis. Hallucinations (whether from psychiatric or medical causes) are significantly associated with agitation.9 In particular, auditory command hallucinations have been linked to agitation. Command hallucinations in children and adolescents may be secondary to early-onset schizophrenia; however, this diagnosis is rare.10 Hallucinations can also be an adverse effect of amphetamine-based stimulant medications in children and adolescents. Visual hallucinations are most often a sign of an underlying medical disorder such as delirium, occipital lobe mass/infection, or drug intoxication or withdrawal. Hallucinations need to be distinguished from the normal, imaginative play of a young child.10

Bipolar mania. In adults, bipolar disorder is a primary psychiatric cause of agitation. In children and adolescents, the diagnosis of bipolar disorder can be complex and requires careful and nuanced history-taking. The risks of agitation are greater with bipolar disorder than with unipolar depression.11,12

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. Prior to DSM-5, many children and adolescents with chronic, non-episodic irritability and severe outbursts out of proportion to the situation or stimuli were given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. These symptoms, in combination with other symptoms, are now considered part of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder when severe outbursts in a child or adolescent occur 3 to 4 times a week consistently, for at least 1 year. The diagnosis of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder requires ruling out other psychiatric and medical conditions, particularly ADHD.13

Substance intoxication/withdrawal. Intoxication or withdrawal from substances such as alcohol, stimulant medications, opioids, methamphetamines, and other agents can lead to agitation. This is more likely to occur among adolescents than children.14

Adjustment disorder. Parental divorce, especially if it is conflictual, or other life stressors, such as experiencing a move or frequent moves, may contribute to the development of agitation in children and adolescents.

Continue to: Depression

Depression. In children and adolescents, depression can manifest as anger or irritability, and occasionally as agitation.

Medical causes

Delirium. Refractory agitation is often a manifestation of delirium in children and adolescents.15 If unrecognized and untreated, delirium can be fatal.16 Therefore, it is imperative that clinicians routinely assess for delirium in any patient who presents with agitation.

Because a patient with delirium often presents with agitation and visual or auditory hallucinations, the medical team may tend to assume these symptoms are secondary to a psychiatric disorder. In this case, the role of the consultation-liaison psychiatrist is critical for guiding the medical team, particularly to continue a thorough exploration of underlying causes while avoiding polypharmacy. Noise, bright lights, frequent changes in nursing staff or caregivers, anticholinergic or benzodiazepine medications, and frequent changes in schedules should be avoided to prevent delirium from occurring or getting worse.17 A multidisciplinary team approach is key in identifying the underlying cause and managing delirium in pediatric patients.

Traumatic brain injury. Agitation may be a presenting symptom in youth with traumatic brain injury (TBI).18 Agitation may present often in the acute recovery phase.19 There is limited evidence on the efficacy and safety of pharmacotherapy for agitation in pediatric patients with TBI.18

Autoimmune conditions. In a study of 27 patients with

Continue to: Medication-induced/iatrogenic

Medication-induced/iatrogenic. Agitation can be an adverse effect of medications such as amantadine (often used for TBI),18 atypical antipsychotics,21 selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

Infection. Agitation can be a result of encephalitis, meningitis, or other infectious processes.22

Metabolic conditions. Hepatic or renal failure, diabetic ketoacidosis, and thyroid toxicosis may cause agitation in children or adolescents.22

Start with nonpharmacologic interventions

Few studies have examined de-escalation techniques in agitated children and adolescents. However, verbal de-escalation is generally viewed as the first-line technique for managing agitation in children and adolescents. When feasible, teaching and modeling developmentally appropriate stress management skills for children and teens can be a beneficial preventative strategy to reduce the incidence and worsening of agitation.23

Clinicians should refrain from using coercion.24 Coercion could harm the therapeutic alliance, thereby impeding assessment of the underlying causes of agitation, and can be particularly harmful for patients who have a history of trauma or abuse. Even in pediatric patients with no such history, coercion is discouraged due to its punitive connotations and potential to adversely impact a vulnerable child or teen.

Continue to: Establishing a therapeutic rapport...

Establishing a therapeutic rapport with the patient, when feasible, can facilitate smoother de-escalation by offering the patient an outlet to air his/her frustrations and emotions, and by helping the patient feel understood.24 To facilitate this, ensure that the patient’s basic comforts and needs are met, such as access to a warm bed, food, and safety.25

The psychiatrist’s role is to help uncover and address the underlying reason for the patient’s agony or distress. Once the child or adolescent has calmed, explore potential triggers or causes of the agitation.

There has been a significant move away from the use of restraints for managing agitation in children and adolescents.26 Restraints have a psychologically traumatizing effect,27 and have been linked to life-threatening injuries and death in children.24

Pharmacotherapy: Proceed with caution

There are no FDA-approved medications for the treatment of agitation in the general pediatric population, and any medication use in this population is off-label. There is also a dearth of research examining the safety and efficacy of using psychotropic medications for agitation in pediatric patients. Because children and adolescents are more susceptible to adverse effects and risks associated with the use of psychotropic medications, special caution is warranted. In general, pharmacologic interventions are not recommended without the use of psychotherapy-based modalities.

In the past, the aim of using medications to treat patients with agitation was to put the patient to sleep.25 This practice did not help clinicians to assess for underlying causes, and was often accompanied by a greater risk of adverse effects and reactions.24 Therefore, the goal of medication treatment for agitation is to help calm the patient instead of inducing sleep.25

Continue to: Pharmacotherapy should...

Pharmacotherapy should be used only when behavioral interventions have been unsuccessful. Key considerations for using psychotropic medications to address agitation in children and adolescents are summarized in Table 2.25

Antipsychotics, particularly second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), have been commonly used to manage acute agitation in children and adolescents, and there has been an upswing in the use of these medications in the United States in the last several years.28 Research indicates that males, children and adolescents in foster care, and those with Medicaid have been the more frequent youth recipients of SGAs.29 Of particular concern is the prevalence of antipsychotic use among children younger than age 6. In the last few decades, there has been an increase in the prescription of antipsychotics for children younger than age 6, particularly for disruptive behavior and aggression.30 In a study of preschool-age Medicaid patients in Kentucky, 70,777 prescriptions for SGAs were given to 6,915 children <6 years of age; 73% of these prescriptions were for male patients.30 Because there is a lack of controlled studies examining the safety and efficacy of SGAs among children and adolescents, especially with long-term use, further research is needed and caution is warranted.28

The FDA has approved

Externalizing disorders among children and adolescents tend to get treated with antipsychotics.28 A Canadian study examining records of 6,916 children found that most children who had been prescribed risperidone received it for ADHD or conduct disorder, and most patients had not received laboratory testing for monitoring the antipsychotic medication they were taking.31 In a 2018 study examining medical records of 120 pediatric patients who presented to an ED in British Columbia with agitation, antipsychotics were the most commonly used medications for patients with autism spectrum disorder; most patients received at least 1 dose.14

For children and adolescents with agitation or aggression who were admitted to inpatient units, IM

Continue to: In case reports...

In case reports, a combination of olanzapine with CNS-suppressing agents has resulted in death. Therefore, do not combine olanzapine with agents such as benzodiazepines.25 In a patient with a likely medical source of agitation, insufficient evidence exists to support the use of olanzapine, and additional research is needed.25

Low-dose haloperidol has been found to be effective for delirium-related agitation in pediatric studies.15 Before initiating an antipsychotic for any child or adolescent, review the patient’s family history for reports of early cardiac death and the patient’s own history of cardiac symptoms, palpitations, syncope, or prolonged QT interval. Monitor for QT prolongation. Among commonly used antipsychotics, the risk of QT prolongation is higher with IV administration of haloperidol and with ziprasidone. Studies show that compared with oral or IM

A few studies have found risperidone to be efficacious for treating ODD and conduct disorder; however, this use is off-label, and its considerable adverse effect and risk profile needs to be weighed against the potential benefit.8

Antipsychotic polypharmacy should be avoided because of the higher risk of adverse effects and interactions, and a lack of robust, controlled studies evaluating the safety of using antipsychotics for non-FDA-approved indications in children and adolescents.7 All patients who receive antipsychotics require monitoring for extrapyramidal symptoms, tardive dyskinesia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, orthostatic hypotension, sedation, metabolic syndrome, and other potential adverse effects. Patients receiving risperidone need to have their prolactin levels monitored periodically, and their parents should be made aware of the potential for hyperprolactinemia and other adverse effects. Aripiprazole and quetiapine may increase the risk of suicidality.

Antiepileptics. A meta-analysis of 7 randomized controlled trials examining the use of antiepileptic medications (

Continue to: In a retrospective case series...

In a retrospective case series of 30 pediatric patients with autism spectrum disorder who were given oxcarbazepine, Douglas et al35 found that 47% of participants experienced significant improvement in irritability/agitation. However, 23% of patients reported significant adverse effects leading to discontinuation. Insufficient evidence exists for the safety and efficacy of oxcarbazepine in this population.35

Benzodiazepines. The use of benzodiazepines in pediatric patients has been associated with paradoxical disinhibition reactions, particularly in children with autism and other developmental or cognitive disabilities or delays.21 There is a lack of data on the safety and efficacy of long-term use of benzodiazepines in children, especially in light of these patients’ developing brains, the risk of cognitive impairment, and the potential for dependence with long-term use. Despite this, some studies show that the use of benzodiazepines is fairly common among pediatric patients who present to the ED with agitation.14 In a recent retrospective study, Kendrick et al14 found that among pediatric patients with agitation who were brought to the ED, benzodiazepines were the most commonly prescribed medications.

Other medications. Clonidine and

Diphenhydramine, in both oral and IM forms, has been used to treat agitation in children,32 but has also been associated with a paradoxical disinhibition reaction in pediatric patients21 and therefore should be used only sparingly and with caution. Diphenhydramine has anticholinergic properties, and may worsen delirium.15 Stimulant medications can help aggressive behavior in children and adolescents with ADHD.37

Bottom Line

Agitation among children and adolescents has many possible causes. A combination of a comprehensive assessment and evidence-based, judicious treatment interventions can help prevent and manage agitation in this vulnerable population.

Related Resources

- Baker M, Carlson GA. What do we really know about PRN use in agitated children with mental health conditions: a clinical review. Evid Based Ment Health. 2018;21(4):166-170.

- Gerson R, Malas N, Mroczkowski MM. Crisis in the emergency department: the evaluation and management of acute agitation in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2018;27(3):367-386.

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Symmetrel

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Clonidine • Catapres

Guanfacine • Intuniv, Tenex

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Levetiracetam • Keppra, Spritam

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Oxcarbazepine • Trileptal

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Topiramate • Topamax

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valproate • Depakene

Ziprasidone • Geodon

1. Frosch E, Kelly P. Issues in pediatric psychiatric emergency care. In: Emergency psychiatry. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2011:185-199.

2. American College of Emergency Physicians. Pediatric mental health emergencies in the emergency department. https://www.acep.org/patient-care/policy-statements/pediatric-mental-health-emergencies-in-the-emergency-medical-services-system/. Revised September 2018. Accessed February 23, 2019.

3. Voepel-Lewis, T, Burke C, Hadden S, et al. Nurses’ diagnoses and treatment decisions regarding care of the agitated child. J Perianesth Nurs. 2005;20(4):239-248.

4. Malas N, Spital L, Fischer J, et al. National survey on pediatric acute agitation and behavioral escalation in academic inpatient pediatric care settings. Psychosomatics. 2017;58(3):299-306.

5. Famularo R, Kinscherff R, Fenton T. Symptom differences in acute and chronic presentation of childhood post-traumatic stress disorder. Child Abuse Negl. 1990;14(3):439-444.

6. Kaminer D, Seedat S, Stein DJ. Post-traumatic stress disorder in children. World Psychiatry. 2005;4(2):121-125.

7. Ninan A, Stewart SL, Theall LA, et al. Adverse effects of psychotropic medications in children: predictive factors. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23(3):218-225.

8. Pringsheim T, Hirsch L, Gardner D, et al. The pharmacological management of oppositional behaviour, conduct problems, and aggression in children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Part 2: antipsychotics and traditional mood stabilizers. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(2):52-61.

9. Vareilles D, Bréhin C, Cortey C, et al. Hallucinations: Etiological analysis of children admitted to a pediatric emergency department. Arch Pediatr. 2017;24(5):445-452.

10. Bartlett J. Childhood-onset schizophrenia: what do we really know? Health Psychol Behav Med. 2014;2(1):735-747.

11. Diler RS, Goldstein TR, Hafeman D, et al. Distinguishing bipolar depression from unipolar depression in youth: Preliminary findings. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(4):310-319.

12. Dervic K, Garcia-Amador M, Sudol K, et al. Bipolar I and II versus unipolar depression: clinical differences and impulsivity/aggression traits. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(1):106-113.

13. Masi L, Gignac M ADHD and DMDD comorbidities, similarities and distinctions. J Child Adolesc Behav2016;4:325.

14. Kendrick JG, Goldman RD, Carr RR. Pharmacologic management of agitation and aggression in a pediatric emergency department - a retrospective cohort study. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2018;23(6):455-459.

15. Schieveld JN, Staal M, Voogd L, et al. Refractory agitation as a marker for pediatric delirium in very young infants at a pediatric intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(11):1982-1983.

16. Traube C, Silver G, Gerber LM, et al. Delirium and mortality in critically ill children: epidemiology and outcomes of pediatric delirium. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(5):891-898.

17. Bettencourt A, Mullen JE. Delirium in children: identification, prevention, and management. Crit Care Nurse. 2017;37(3):e9-e18.

18. Suskauer SJ, Trovato MK. Update on pharmaceutical intervention for disorders of consciousness and agitation after traumatic brain injury in children. PM R. 2013;5(2):142-147.

19. Nowicki M, Pearlman L, Campbell C, et al. Agitated behavior scale in pediatric traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2019. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2019.1565893.

20. Mohammad SS, Jones H, Hong M, et al. Symptomatic treatment of children with anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58(4):376-384.

21. Sonnier L, Barzman D. Pharmacologic management of acutely agitated pediatric patients. Pediatr Drugs. 2011;13(1):1-10.

22. Nordstrom K, Zun LS, Wilson MP, et al. Medical evaluation and triage of the agitated patient: consensus statement of the american association for emergency psychiatry project Beta medical evaluation workgroup. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13(1):3-10.

23. Masters KJ, Bellonci C, Bernet W, et al; American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameter for the prevention and management of aggressive behavior in child and adolescent psychiatric institutions, with special reference to seclusion and restraint. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(2 suppl):4S-25S.

24. Croce ND, Mantovani C. Using de-escalation techniques to prevent violent behavior in pediatric psychiatric emergencies: It is possible. Pediatric Dimensions, 2017;2(1):1-2.

25. Marzullo LR. Pharmacologic management of the agitated child. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(4):269-275.

26. Caldwell B, Albert C, Azeem MW, et al. Successful seclusion and restraint prevention effort in child and adolescent programs. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2014;52(11):30-38.

27. De Hert M, Dirix N, Demunter H, et al. Prevalence and correlates of seclusion and restraint use in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20(5):221-230.

28. Crystal S, Olfson M, Huang C, et al. Broadened use of atypical antipsychotics: safety, effectiveness, and policy challenges. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(5):w770-w781.

29. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the use of atypical antipsychotic medication in children and adolescents. https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/docs/practice_parameters/Atypical_Antipsychotic_Medications_Web.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2019.

30. Lohr WD, Chowning RT, Stevenson MD, et al. Trends in atypical antipsychotics prescribed to children six years of age or less on Medicaid in Kentucky. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2015;25(5):440-443.

31. Chen W, Cepoiu-Martin M, Stang A, et al. Antipsychotic prescribing and safety monitoring practices in children and youth: a population-based study in Alberta, Canada. Clin Drug Investig. 2018;38(5):449-455.

32. Deshmukh P, Kulkarni G, Barzman D. Recommendations for pharmacological management of inpatient aggression in children and adolescents. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2010;7(2):32-40.

33. Haldol [package insert]. Beerse, Belgium: Janssen Pharmaceutica NV; 2005.

34. Hirota T, Veenstra-Vanderweele J, Hollander E, et al. Antiepileptic medications in autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(4):948-957.

35. Douglas JF, Sanders KB, Benneyworth MH, et al. Brief report: retrospective case series of oxcarbazepine for irritability/agitation symptoms in autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(5):1243-1247.

36. Harmon RJ, Riggs PD. Clonidine for posttraumatic stress disorder in preschool children. J Am Acad

37. Pringsheim T, Hirsch L, Gardner D, et al. The pharmacological management of oppositional behaviour, conduct problems, and aggression in children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Part 1: Psychostimulants, alpha-2 Agonists, and atomoxetine. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(2):42-51

1. Frosch E, Kelly P. Issues in pediatric psychiatric emergency care. In: Emergency psychiatry. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2011:185-199.

2. American College of Emergency Physicians. Pediatric mental health emergencies in the emergency department. https://www.acep.org/patient-care/policy-statements/pediatric-mental-health-emergencies-in-the-emergency-medical-services-system/. Revised September 2018. Accessed February 23, 2019.

3. Voepel-Lewis, T, Burke C, Hadden S, et al. Nurses’ diagnoses and treatment decisions regarding care of the agitated child. J Perianesth Nurs. 2005;20(4):239-248.

4. Malas N, Spital L, Fischer J, et al. National survey on pediatric acute agitation and behavioral escalation in academic inpatient pediatric care settings. Psychosomatics. 2017;58(3):299-306.

5. Famularo R, Kinscherff R, Fenton T. Symptom differences in acute and chronic presentation of childhood post-traumatic stress disorder. Child Abuse Negl. 1990;14(3):439-444.

6. Kaminer D, Seedat S, Stein DJ. Post-traumatic stress disorder in children. World Psychiatry. 2005;4(2):121-125.

7. Ninan A, Stewart SL, Theall LA, et al. Adverse effects of psychotropic medications in children: predictive factors. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23(3):218-225.

8. Pringsheim T, Hirsch L, Gardner D, et al. The pharmacological management of oppositional behaviour, conduct problems, and aggression in children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Part 2: antipsychotics and traditional mood stabilizers. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(2):52-61.

9. Vareilles D, Bréhin C, Cortey C, et al. Hallucinations: Etiological analysis of children admitted to a pediatric emergency department. Arch Pediatr. 2017;24(5):445-452.