User login

Evaluation after a suicide attempt: What to ask

In 2021, suicide was the 11th leading cause of death in the United States.1 Suicide resulted in 49,000 US deaths during 2021; it was the second most common cause of death in individuals age 10 to 34, and the fifth leading cause among children.1,2 Women are 3 to 4 times more likely than men to attempt suicide, but men are 4 times more likely to die by suicide.2

The evaluation of patients with suicidal ideation who have not made an attempt generally involves assessing 4 factors: the specific plan, access to lethal means, any recent social stressors, and the presence of a psychiatric disorder.3 The clinician should also assess which potential deterrents, such as religious beliefs or dependent children, might be present.

Mental health clinicians are often called upon to evaluate a patient after a suicide attempt to assess intent for continued self-harm and to determine appropriate disposition. Such an evaluation must consider multiple factors, including the method used, premeditation, consequences of the attempt, the presence of severe depression and/or psychosis, and the role of substance use. Assessment after a suicide attempt differs from the examination of individuals who harbor suicidal thoughts but have not made an attempt; the latter group may be more likely to respond to interventions such as intensive outpatient care, mobilization of family support, and religious proscriptions against suicide. However, for patients who make an attempt to end their life, whatever potential safeguards or deterrents to suicide that were in place obviously did not prevent the self-harm act. The consequences of the attempt, such as disabling injuries or medical complications, and possible involuntary commitment, need to be considered. Assessment of the patient’s feelings about having survived the attempt is important because the psychological impact of the attempt on family members may serve to intensify the patient’s depression and make a subsequent attempt more likely.

Many individuals who think of suicide have communicated self-harm thoughts or intentions, but such comments are often minimized or ignored. There is a common but erroneous belief that if patients are encouraged to discuss thoughts of self-harm, they will be more likely to act upon them. Because the opposite is true,4 clinicians should ask vulnerable patients about suicidal ideation or intent. Importantly, noncompliance with life-saving medical care, risk-taking behaviors, and substance use may also signal a desire for self-harm. Passive thoughts of death, typified by comments such as “I don’t care whether I wake up or not,” should also be elicited. Many patients who think of suicide speak of being in a “bad place” where reason and logic give way to an intense desire to end their misery.

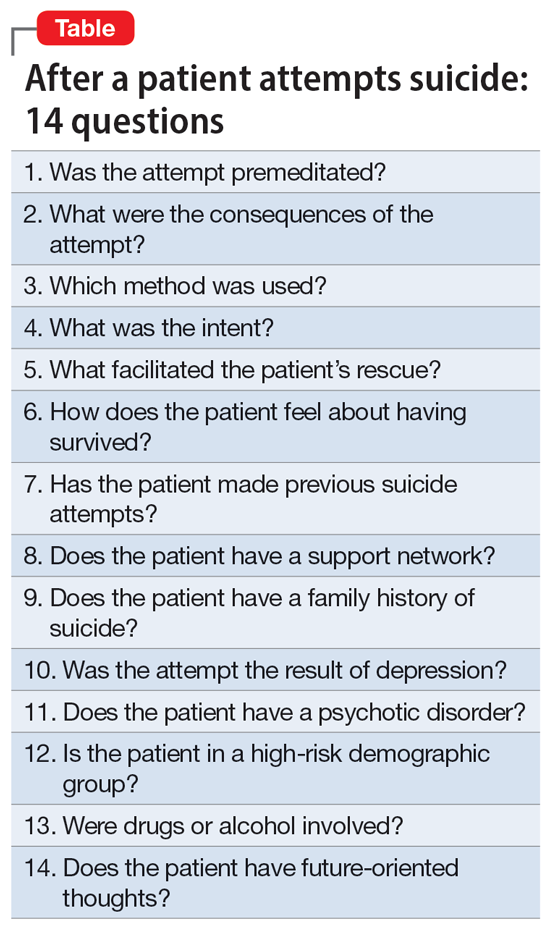

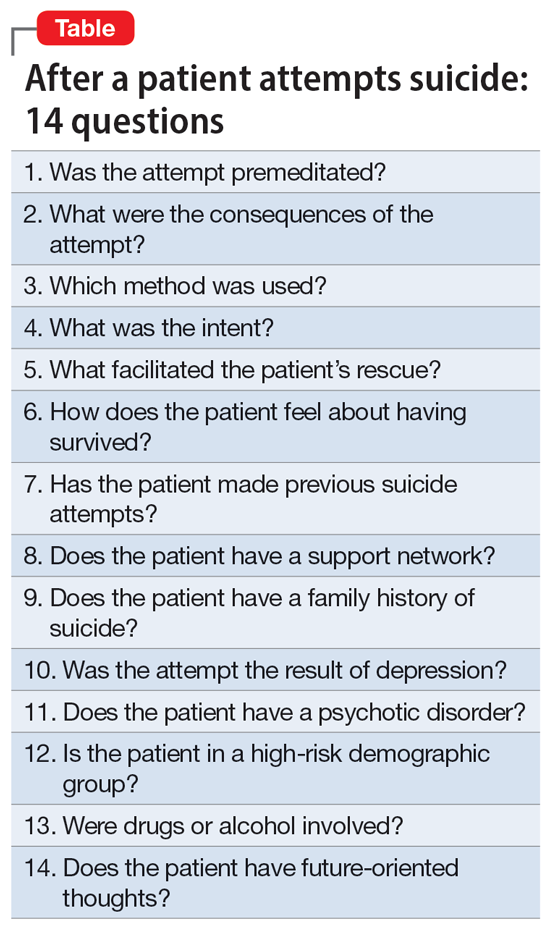

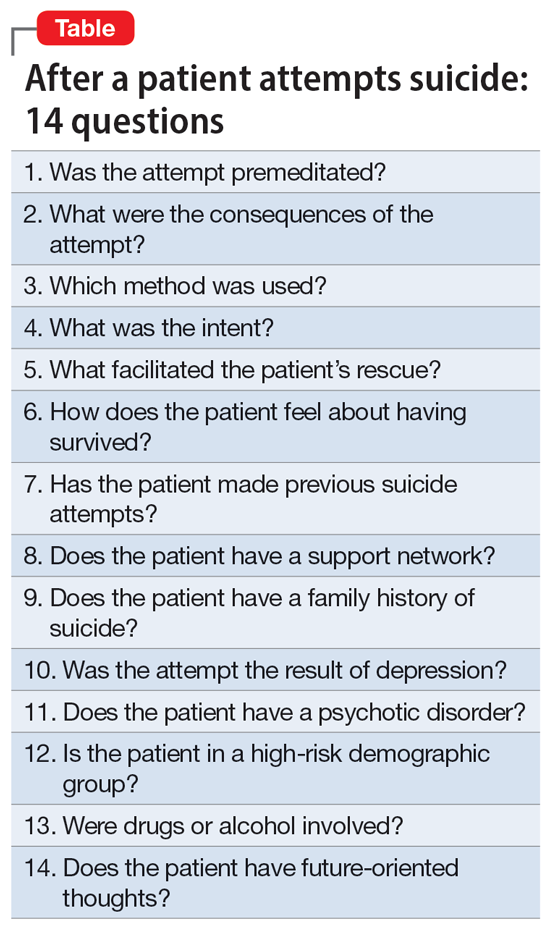

The evaluation of a patient who has attempted suicide is an important component of providing psychiatric care. This article reflects our 45 years of evaluating such patients. As such, it reflects our clinical experience and is not evidence-based. We offer a checklist of 14 questions that we have found helpful when determining if it would be best for a patient to receive inpatient psychiatric hospitalization or a discharge referral for outpatient care (Table). Questions 1 through 6 are specific for patients who have made a suicide attempt, while questions 7 through 14 are helpful for assessing global risk factors for suicide.

1. Was the attempt premeditated?

Determining premeditation vs impulsivity is an essential element of the assessment following a suicide attempt. Many such acts may occur without forethought in response to an unexpected stressor, such as an altercation between partners or family conflicts. Impulsive attempts can occur when an individual is involved in a distressing event and/or while intoxicated. Conversely, premeditation involves forethought and planning, which may increase the risk of suicide in the near future.

Examples of premeditated behavior include:

- Contemplating the attempt days or weeks beforehand

- Researching the effects of a medication or combination of medications in terms of potential lethality

- Engaging in behavior that would decrease the likelihood of their body being discovered after the attempt

- Obtaining weapons and/or stockpiling pills

- Canvassing potential sites such as bridges or tall buildings

- Engaging in a suicide attempt “practice run”

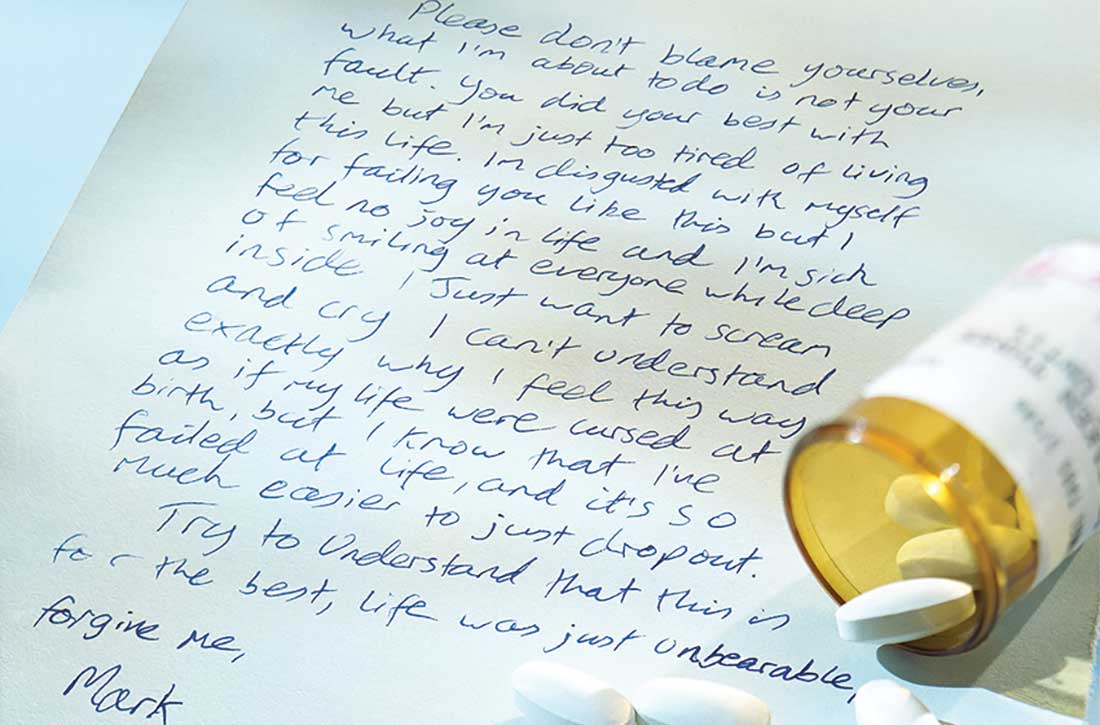

- Leaving a suicide note or message on social media

- Making funeral arrangements, such as choosing burial clothing

- Writing a will and arranging for the custody of dependent children

- Purchasing life insurance that does not deny payment of benefits in cases of death by suicide.

Continue to: Patients with a premeditated...

Patients with a premeditated suicide attempt generally do not expect to survive and are often surprised or upset that the act was not fatal. The presence of indicators that the attempt was premeditated should direct the disposition more toward hospitalization than discharge. In assessing the impact of premeditation, it is important to gauge not just the examples listed above, but also the patient’s perception of these issues (such as potential loss of child custody). Consider how much the patient is emotionally affected by such thinking.

2. What were the consequences of the attempt?

Assessing the reason for the attempt (if any) and determining whether the inciting circumstance has changed due to the suicide attempt are an important part of the evaluation. A suicide attempt may result in reconciliation with and/or renewed support from family members or partners, who might not have been aware of the patient’s emotional distress. Such unexpected support often results in the patient exhibiting improved mood and affect, and possibly temporary resolution of suicidal thoughts. This “flight into health” may be short-lived, but it also may be enough to engage the patient in a therapeutic alliance. That may permit a discharge with safe disposition to the outpatient clinic while in the custody of a family member, partner, or close friend.

Alternatively, some people experience a troubling worsening of precipitants following a suicide attempt. Preexisting medical conditions and financial, occupational, and/or social woes may be exacerbated. Child custody determinations may be affected, assuming the patient understands the possibility of this adverse consequence. Violent methods may result in disfigurement and body image issues. Individuals from small, close-knit communities may experience stigmatization and unwanted notoriety because of their suicide attempt. Such negative consequences may render some patients more likely to make another attempt to die by suicide. It is crucial to consider how a suicide attempt may have changed the original stress that led to the attempt.

3. Which method was used?

Most fatal suicides in the US are by firearms, and many individuals who survive such attempts do so because of unfamiliarity with the weapon, gun malfunction, faulty aim, or alcohol use.5-7 Some survivors report intending to shoot themselves in the heart, but instead suffered shoulder injuries. Unfortunately, for a patient who survives self-inflicted gunshot wounds, the sequelae of chronic pain, multiple surgical procedures, disability, and disfigurement may serve as constant negative reminders of the event. Some individuals with suicidal intent eschew the idea of using firearms because they hope to avoid having a family member be the first to discover them. Witnessing the aftermath of a fatal suicide by gunshot can induce symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in family members and/or partners.8

For a patient with self-inflicted gunshot wounds, always determine whether the weapon has been secured or if the patient still has access to it. Asking about weapon availability is essential during the evaluation of any patient with depression, major life crises, or other factors that may yield a desire to die; this is especially true for individuals with substance use disorders (SUDs). Whenever readily available to such individuals, weapons need to be safely removed.

Continue to: Other self-harm methods...

Other self-harm methods with a high degree of lethality include jumping from bridges or buildings, poisonings, self-immolation, cutting, and hangings. Individuals who choose these approaches generally do not intend to survive. Many of these methods also entail premeditation, as in the case of individuals who canvass bridges and note time when traffic is light so they are less likely to be interrupted. Between 1937 and 2012, there were >1,600 deaths by suicide from San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge.9 Patients who choose highly lethal methods are often irritated during the postattempt evaluation because their plans were not fatal. Usually, patients who choose such potentially lethal methods are hospitalized initially on medical and surgical floors, and receive most of their psychiatric care from consultation psychiatrists. Following discharge, these patients may be at high risk for subsequent suicide attempts.

In the US, the most common method of attempting suicide is by overdose.4 Lethality is determined by the agent or combination of substances ingested, the amount taken, the person’s health status, and the length of time before they are discovered. Many patients mistakenly assume that readily available agents such as acetaminophen and aspirin are less likely to be fatal than prescription medications. Evaluators may want to assess for suicidality in individuals with erratic, risk-taking behaviors, who are at especially high risk for death. Learning about the method the patient used can help the clinician determine the imminent risk of another suicide attempt. The more potentially fatal the patient’s method, the more serious their suicide intent, and the higher the risk they will make another suicide attempt, possibly using an even more lethal method.

4. What was the intent?

“What did you want to happen when you made this attempt?” Many patients will respond that they wanted to die, sleep, not wake up, or did not care what happened. Others say it was a gesture to evoke a certain response from another person. If this is the case, it is important to know whether the desired outcome was achieved. These so-called gestures often involve making sure the intended person is aware of the attempt, often by writing a letter, sending a text, or posting on social media. Such behaviors may be exhibited by patients with personality disorders. While such attempts often are impulsive, if the attempt fails to generate the anticipated effect, the patient may try to gain more attention by escalating their suicide actions.

Conversely, if a spouse or partner reconciles with the patient solely because of a suicide attempt, this may set a pattern for future self-harm events in which the patient hopes to achieve the same outcome. Nevertheless, it is better to err for safety because some of these patients will make another attempt, just to prove that they should have been taken more seriously. An exploration of such intent can help the evaluation because even supposed “gestures” can have dangerous consequences. Acts that do not result in the desired outcome should precipitate hospitalization rather than discharge.

5. What facilitated the patient’s rescue?

“Why is this patient still alive?” Determine if the patient did anything to save themself, such as calling an ambulance, inducing emesis, telling someone what they did, or coming to the hospital on their own. If yes, asking them what changed their mind may provide information about what exists in their lives to potentially prevent future attempts, or about wishes to stay alive. These issues can be used to guide outpatient therapy.

Continue to: How does the patient feel about having survived?

6. How does the patient feel about having survived?

When a patient is asked how they feel about having survived a suicide attempt, some will label their act “stupid” and profess embarrassment. Others exhibit future-oriented thought, which is a very good prognostic sign. More ominous is subsequent dysphoria or lamenting that “I could not even do this right.” Patients often express anger toward anyone who rescued them, especially those whose attempts were carefully planned or were discovered by accident. Some patients might also express ambivalence about having survived.

The patient’s response to this question may be shaped by their desire to avoid hospitalization, so beyond their verbal answers, be attentive to clinical cues that may suggest the patient is not being fully transparent. Anger or ambivalence about having survived, a lack of future-oriented thought, and a restricted affect despite verbalizing joy about still being alive are features that suggest psychiatric hospitalization may be warranted.

7. Has the patient made previous suicide attempts?

Compared to individuals with no previous suicide attempts, patients with a history of suicide attempts are 30 to 40 times more likely to die by suicide.2 Many patients who present after a suicide attempt have tried to kill themselves multiple times. Exploring the number of past attempts, how recent the attempts were, and what dispositions were made can be of benefit. Reviewing the potential lethality of past attempts (eg, was hospitalization required, was the patient placed in an intensive care unit, and/or was intubation needed) is recommended. If outpatient care was suggested or medication prescribed, was the patient adherent? Consider asking about passive suicidal behavior, such as not seeking care for medical issues, discontinuing life-saving medication, or engaging in reckless behavior. While such behaviors may not have been classified as a suicide attempt, it might indicate a feeling of indifference toward staying alive. A patient with a past attempt, especially if recent, merits consideration for inpatient care. Once again, referring previously nonadherent patients to outpatient treatment is less likely to be effective.

8. Does the patient have a support network?

Before discharging a patient who has made a suicide attempt, consider the quality of their support network. Gauging the response of the family and friends to the patient’s attempt can be beneficial. Indifference or resentment on the part of loved ones is a bad sign. Some patients have access to support networks they either did not know were available or chose not to utilize. In other instances, after realizing how depressed the patient has been, the family might provide a new safety net. Strong religious affiliations can also be valuable because devout spirituality can be a deterrent to suicide behaviors.10 For an individual whose attempt was motivated by loneliness or feeling unloved or underappreciated, a newly realized support network can be an additional protective deterrent.

9. Does the patient have a family history of suicide?

There may be a familial component to suicide. Knowing about any suicide history in the family contributes to future therapeutic planning. The clinician may want to explore the patient’s family suicide history in detail because such information can have substantial impact on the patient’s motivation for attempting suicide. The evaluator may want to determine if the anniversary of a family suicide is coming. Triggers for a suicide attempt could include the anniversary of a death, birthdays, family-oriented holidays, and similar events. It is productive to understand how the patient feels about family members who have died by suicide. Some will empathize with the deceased, commenting that they did the “right thing.” Others, upon realizing how their own attempt affected others, will be remorseful and determined not to inflict more pain on their family. Such patients may need to be reminded of the misery associated with their family being left without them. These understandings are helpful at setting a safe disposition. However, a history of death by suicide in the family should always be thoroughly evaluated, regardless of the patient’s attitude about that death.

Continue to: Was the attempt the result of depression?

10. Was the attempt the result of depression?

For a patient experiencing depressive symptoms, the prognosis is less positive; they are more likely to harbor serious intent, premeditation, hopelessness, and social isolation, and less likely to express future-oriented thought. They often exhibit a temporary “flight into health.” Such progress is often transitory and may not represent recovery. Because mood disorders may still be present despite a temporary improvement, inpatient and pharmacologic treatment may be needed. If a patient’s suicide attempt occurred as a result of severe depression, it is possible they will make another suicide attempt unless their depression is addressed in a safe and secure setting, such as inpatient hospitalization, or through close family observation while the patient is receiving intensive outpatient treatment.

11. Does the patient have a psychotic disorder?

Many patients with a psychotic illness die following their first attempt without ever having contact with a mental health professional.11 Features of psychosis might include malevolent auditory hallucinations that suggest self-destruction.11 Such “voices” can be intense and self-deprecating; many patients with this type of hallucination report having made a suicide attempt “just to make the voices stop.”

Symptoms of paranoia can make it less likely for individuals with psychosis to confide in family members, friends, or medical personnel. Religious elements are often of a delusional nature and can be dangerous. Psychosis is more difficult to hide than depression and the presence of psychoses concurrent with major depressive disorder (MDD) increases the probability of suicidality.11 Psychosis secondary to substance use may diminish inhibitions and heighten impulsivity, thereby exacerbating the likelihood of self-harm. Usually, the presence of psychotic features precipitating or following a suicide attempt leads to psychiatric hospitalization.

12. Is the patient in a high-risk demographic group?

When evaluating a patient who has attempted suicide, it helps to consider not just what they did, but who they are. Specifically, does the individual belong to a demographic group that traditionally has a high rate of suicide? For example, patients who are Native American or Alaska Natives warrant extra caution.2 Older White males, especially those who are divorced, widowed, retired, and/or have chronic health problems, are also at greater risk. Compared to the general population, individuals age >80 have a massively elevated chance for self-induced death.12 Some of the reasons include:

- medical comorbidities make surviving an attempt less likely

- access to large amounts of medications

- more irreversible issues, such as chronic pain, disability, or widowhood

- living alone, which may delay discovery.

Patients who are members of any of these demographic groups may deserve serious consideration for inpatient psychiatric admission, regardless of other factors.

Continue to: Were drugs or alcohol involved?

13. Were drugs or alcohol involved?

This factor is unique in that it is both a chronic risk factor (SUDs) and a warning sign for imminent suicide, as in the case of an individual who gets intoxicated to disinhibit their fear of death so they can attempt suicide. Alcohol use disorders are associated with depression and suicide. Overdoses by fentanyl and other opiates have become more frequent.13 In many cases, fatalities are unintentional because users overestimate their tolerance or ingest contaminated substances.14 Disinhibition by alcohol and/or other drugs is a risk factor for attempting suicide and can intensify the depth of MDD. Some patients will ingest substances before an attempt just to give them the courage to act; many think of suicide only when intoxicated. Toxicology screens are indicated as part of the evaluation after a suicide attempt.

Depressive and suicidal thoughts often occur in people “coming down” from cocaine or other stimulants. These circumstances require determining whether to refer the patient for treatment for an SUD or psychiatric hospitalization.

In summary, getting intoxicated solely to diminish anxiety about suicide is a dangerous feature, whereas attempting suicide due to intoxication is less concerning. The latter patient may not consider suicide unless they become intoxicated again. When available, dual diagnosis treatment facilities can be an appropriate referral for such patients. Emergency department holding beds can allow these individuals to detoxify prior to the evaluation.

14. Does the patient have future-oriented thoughts?

When evaluating a patient who has attempted suicide, the presence of future planning and anticipation can be reassuring, but these features should be carefully assessed.14-16

After-the-fact comments may be more reliable when a patient offers them spontaneously, as opposed to in response to direct questioning.

- the specificity of the future plans

- corroboration from the family and others about the patient’s previous investment in the upcoming event

- whether the patient mentions such plans spontaneously or only in response to direct questioning

- the patient’s emotional expression or affect when discussing their future

- whether such plans are reasonable, grandiose, and/or unrealistic.

Bottom Line

When assessing a patient after a suicide attempt, both the patient’s presentation and history and the clinician’s instincts are important. Careful consideration of the method, stated intent, premeditation vs impulsivity, feelings about having survived, presence of psychiatric illness, high-risk demographic, postattempt demeanor and affect, quality of support, presence of self-rescue behaviors, future-oriented thoughts, and other factors can help in making the appropriate disposition.

Related Resources

- Kim H, Kim Y, Shin MH, et al. Early psychiatric referral after attempted suicide helps prevent suicide reattempts: a longitudinal national cohort study in South Korea. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:607892. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.607892

- Michaud L, Berva S, Ostertag L, et al. When to discharge and when to voluntary or compulsory hospitalize? Factors associated with treatment decision after self-harm. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114810. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114810

1. Ten Leading Causes of Death, United States 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention WISQARS. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://wisqars.cdc.gov/data/lcd/home

2. Norris D, Clark MS. Evaluation and treatment of suicidal patients. Am Fam Physician. 2012;15;85(6):602-605.

3. Gliatto MF, Rai AK. Evaluation and treatment patients with suicidal ideation. Am Fam Phys. 1999;59(6):1500-1506.

4. Dazzi T, Gribble R, Wessely S, et al. Does asking about suicide and related behaviors induce suicidal ideation? What is the evidence? Psychol Med. 2014;44(16):3361-3363.

5. Lewiecki EM, Miller SA. Suicide, guns and public policy. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(1):27-31.

6. Frierson RL. Women who shoot themselves. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1989;40(8):841-843.

7. Frierson RL, Lippmann SB. Psychiatric consultation for patients with self-inflicted gunshot wounds. Psychosomatics. 1990;31(1):67-74.

8. Mitchell AM, Terhorst L. PTSD symptoms in survivors bereaved by the suicide of a significant other. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2017;23(1):61-65.

9. Bateson J. The Golden Gate Bridge’s fatal flaw. Los Angeles Times. May 25, 2012. Accessed March 2, 2022. https://www.latimes.com/opinion/la-xpm-2012-may-25-la-oe-adv-bateson-golden-gate-20120525-story.html

10. Dervic K, Oquendoma MA, Grunebaum MF, et al. Religious affiliation and suicide attempt. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2303-2308.

11. Nordentoft H, Madsen T, Fedyszyn IF. Suicidal behavior and mortality in first episode psychosis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203(5):387-392.

12. Frierson R, Lippmann S. Suicide attempts by the old and the very old. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151(1):141-144.

13. Braden JB, Edlund MJ, Sullivan MD. Suicide deaths with opiate poisonings in the United States: 1999-2014. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(3):421-426.

14. Morin KA, Acharya S, Eibl JK, et al: Evidence of increased fentanyl use during the COVID-19 pandemic among opioid agonist treated patients in Ontario, Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;90:103088.

15. Shobassy A, Abu-Mohammad AS. Assessing imminent suicide risk: what about future planning? Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(2):12-17.

16. MacLeod AK, Pankhania B, Lee M, et al. Parasuicide, depression and the anticipation of positive and negative future experiences. Psychol Med. 1997;27(4):973-977.

17. Macleod AK, Tata P, Tyrer P, et al. Hopelessness and positive and negative future thinking in parasuicide. Br J Clin Psychol. 2010;44(Pt 4):495-504.

In 2021, suicide was the 11th leading cause of death in the United States.1 Suicide resulted in 49,000 US deaths during 2021; it was the second most common cause of death in individuals age 10 to 34, and the fifth leading cause among children.1,2 Women are 3 to 4 times more likely than men to attempt suicide, but men are 4 times more likely to die by suicide.2

The evaluation of patients with suicidal ideation who have not made an attempt generally involves assessing 4 factors: the specific plan, access to lethal means, any recent social stressors, and the presence of a psychiatric disorder.3 The clinician should also assess which potential deterrents, such as religious beliefs or dependent children, might be present.

Mental health clinicians are often called upon to evaluate a patient after a suicide attempt to assess intent for continued self-harm and to determine appropriate disposition. Such an evaluation must consider multiple factors, including the method used, premeditation, consequences of the attempt, the presence of severe depression and/or psychosis, and the role of substance use. Assessment after a suicide attempt differs from the examination of individuals who harbor suicidal thoughts but have not made an attempt; the latter group may be more likely to respond to interventions such as intensive outpatient care, mobilization of family support, and religious proscriptions against suicide. However, for patients who make an attempt to end their life, whatever potential safeguards or deterrents to suicide that were in place obviously did not prevent the self-harm act. The consequences of the attempt, such as disabling injuries or medical complications, and possible involuntary commitment, need to be considered. Assessment of the patient’s feelings about having survived the attempt is important because the psychological impact of the attempt on family members may serve to intensify the patient’s depression and make a subsequent attempt more likely.

Many individuals who think of suicide have communicated self-harm thoughts or intentions, but such comments are often minimized or ignored. There is a common but erroneous belief that if patients are encouraged to discuss thoughts of self-harm, they will be more likely to act upon them. Because the opposite is true,4 clinicians should ask vulnerable patients about suicidal ideation or intent. Importantly, noncompliance with life-saving medical care, risk-taking behaviors, and substance use may also signal a desire for self-harm. Passive thoughts of death, typified by comments such as “I don’t care whether I wake up or not,” should also be elicited. Many patients who think of suicide speak of being in a “bad place” where reason and logic give way to an intense desire to end their misery.

The evaluation of a patient who has attempted suicide is an important component of providing psychiatric care. This article reflects our 45 years of evaluating such patients. As such, it reflects our clinical experience and is not evidence-based. We offer a checklist of 14 questions that we have found helpful when determining if it would be best for a patient to receive inpatient psychiatric hospitalization or a discharge referral for outpatient care (Table). Questions 1 through 6 are specific for patients who have made a suicide attempt, while questions 7 through 14 are helpful for assessing global risk factors for suicide.

1. Was the attempt premeditated?

Determining premeditation vs impulsivity is an essential element of the assessment following a suicide attempt. Many such acts may occur without forethought in response to an unexpected stressor, such as an altercation between partners or family conflicts. Impulsive attempts can occur when an individual is involved in a distressing event and/or while intoxicated. Conversely, premeditation involves forethought and planning, which may increase the risk of suicide in the near future.

Examples of premeditated behavior include:

- Contemplating the attempt days or weeks beforehand

- Researching the effects of a medication or combination of medications in terms of potential lethality

- Engaging in behavior that would decrease the likelihood of their body being discovered after the attempt

- Obtaining weapons and/or stockpiling pills

- Canvassing potential sites such as bridges or tall buildings

- Engaging in a suicide attempt “practice run”

- Leaving a suicide note or message on social media

- Making funeral arrangements, such as choosing burial clothing

- Writing a will and arranging for the custody of dependent children

- Purchasing life insurance that does not deny payment of benefits in cases of death by suicide.

Continue to: Patients with a premeditated...

Patients with a premeditated suicide attempt generally do not expect to survive and are often surprised or upset that the act was not fatal. The presence of indicators that the attempt was premeditated should direct the disposition more toward hospitalization than discharge. In assessing the impact of premeditation, it is important to gauge not just the examples listed above, but also the patient’s perception of these issues (such as potential loss of child custody). Consider how much the patient is emotionally affected by such thinking.

2. What were the consequences of the attempt?

Assessing the reason for the attempt (if any) and determining whether the inciting circumstance has changed due to the suicide attempt are an important part of the evaluation. A suicide attempt may result in reconciliation with and/or renewed support from family members or partners, who might not have been aware of the patient’s emotional distress. Such unexpected support often results in the patient exhibiting improved mood and affect, and possibly temporary resolution of suicidal thoughts. This “flight into health” may be short-lived, but it also may be enough to engage the patient in a therapeutic alliance. That may permit a discharge with safe disposition to the outpatient clinic while in the custody of a family member, partner, or close friend.

Alternatively, some people experience a troubling worsening of precipitants following a suicide attempt. Preexisting medical conditions and financial, occupational, and/or social woes may be exacerbated. Child custody determinations may be affected, assuming the patient understands the possibility of this adverse consequence. Violent methods may result in disfigurement and body image issues. Individuals from small, close-knit communities may experience stigmatization and unwanted notoriety because of their suicide attempt. Such negative consequences may render some patients more likely to make another attempt to die by suicide. It is crucial to consider how a suicide attempt may have changed the original stress that led to the attempt.

3. Which method was used?

Most fatal suicides in the US are by firearms, and many individuals who survive such attempts do so because of unfamiliarity with the weapon, gun malfunction, faulty aim, or alcohol use.5-7 Some survivors report intending to shoot themselves in the heart, but instead suffered shoulder injuries. Unfortunately, for a patient who survives self-inflicted gunshot wounds, the sequelae of chronic pain, multiple surgical procedures, disability, and disfigurement may serve as constant negative reminders of the event. Some individuals with suicidal intent eschew the idea of using firearms because they hope to avoid having a family member be the first to discover them. Witnessing the aftermath of a fatal suicide by gunshot can induce symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in family members and/or partners.8

For a patient with self-inflicted gunshot wounds, always determine whether the weapon has been secured or if the patient still has access to it. Asking about weapon availability is essential during the evaluation of any patient with depression, major life crises, or other factors that may yield a desire to die; this is especially true for individuals with substance use disorders (SUDs). Whenever readily available to such individuals, weapons need to be safely removed.

Continue to: Other self-harm methods...

Other self-harm methods with a high degree of lethality include jumping from bridges or buildings, poisonings, self-immolation, cutting, and hangings. Individuals who choose these approaches generally do not intend to survive. Many of these methods also entail premeditation, as in the case of individuals who canvass bridges and note time when traffic is light so they are less likely to be interrupted. Between 1937 and 2012, there were >1,600 deaths by suicide from San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge.9 Patients who choose highly lethal methods are often irritated during the postattempt evaluation because their plans were not fatal. Usually, patients who choose such potentially lethal methods are hospitalized initially on medical and surgical floors, and receive most of their psychiatric care from consultation psychiatrists. Following discharge, these patients may be at high risk for subsequent suicide attempts.

In the US, the most common method of attempting suicide is by overdose.4 Lethality is determined by the agent or combination of substances ingested, the amount taken, the person’s health status, and the length of time before they are discovered. Many patients mistakenly assume that readily available agents such as acetaminophen and aspirin are less likely to be fatal than prescription medications. Evaluators may want to assess for suicidality in individuals with erratic, risk-taking behaviors, who are at especially high risk for death. Learning about the method the patient used can help the clinician determine the imminent risk of another suicide attempt. The more potentially fatal the patient’s method, the more serious their suicide intent, and the higher the risk they will make another suicide attempt, possibly using an even more lethal method.

4. What was the intent?

“What did you want to happen when you made this attempt?” Many patients will respond that they wanted to die, sleep, not wake up, or did not care what happened. Others say it was a gesture to evoke a certain response from another person. If this is the case, it is important to know whether the desired outcome was achieved. These so-called gestures often involve making sure the intended person is aware of the attempt, often by writing a letter, sending a text, or posting on social media. Such behaviors may be exhibited by patients with personality disorders. While such attempts often are impulsive, if the attempt fails to generate the anticipated effect, the patient may try to gain more attention by escalating their suicide actions.

Conversely, if a spouse or partner reconciles with the patient solely because of a suicide attempt, this may set a pattern for future self-harm events in which the patient hopes to achieve the same outcome. Nevertheless, it is better to err for safety because some of these patients will make another attempt, just to prove that they should have been taken more seriously. An exploration of such intent can help the evaluation because even supposed “gestures” can have dangerous consequences. Acts that do not result in the desired outcome should precipitate hospitalization rather than discharge.

5. What facilitated the patient’s rescue?

“Why is this patient still alive?” Determine if the patient did anything to save themself, such as calling an ambulance, inducing emesis, telling someone what they did, or coming to the hospital on their own. If yes, asking them what changed their mind may provide information about what exists in their lives to potentially prevent future attempts, or about wishes to stay alive. These issues can be used to guide outpatient therapy.

Continue to: How does the patient feel about having survived?

6. How does the patient feel about having survived?

When a patient is asked how they feel about having survived a suicide attempt, some will label their act “stupid” and profess embarrassment. Others exhibit future-oriented thought, which is a very good prognostic sign. More ominous is subsequent dysphoria or lamenting that “I could not even do this right.” Patients often express anger toward anyone who rescued them, especially those whose attempts were carefully planned or were discovered by accident. Some patients might also express ambivalence about having survived.

The patient’s response to this question may be shaped by their desire to avoid hospitalization, so beyond their verbal answers, be attentive to clinical cues that may suggest the patient is not being fully transparent. Anger or ambivalence about having survived, a lack of future-oriented thought, and a restricted affect despite verbalizing joy about still being alive are features that suggest psychiatric hospitalization may be warranted.

7. Has the patient made previous suicide attempts?

Compared to individuals with no previous suicide attempts, patients with a history of suicide attempts are 30 to 40 times more likely to die by suicide.2 Many patients who present after a suicide attempt have tried to kill themselves multiple times. Exploring the number of past attempts, how recent the attempts were, and what dispositions were made can be of benefit. Reviewing the potential lethality of past attempts (eg, was hospitalization required, was the patient placed in an intensive care unit, and/or was intubation needed) is recommended. If outpatient care was suggested or medication prescribed, was the patient adherent? Consider asking about passive suicidal behavior, such as not seeking care for medical issues, discontinuing life-saving medication, or engaging in reckless behavior. While such behaviors may not have been classified as a suicide attempt, it might indicate a feeling of indifference toward staying alive. A patient with a past attempt, especially if recent, merits consideration for inpatient care. Once again, referring previously nonadherent patients to outpatient treatment is less likely to be effective.

8. Does the patient have a support network?

Before discharging a patient who has made a suicide attempt, consider the quality of their support network. Gauging the response of the family and friends to the patient’s attempt can be beneficial. Indifference or resentment on the part of loved ones is a bad sign. Some patients have access to support networks they either did not know were available or chose not to utilize. In other instances, after realizing how depressed the patient has been, the family might provide a new safety net. Strong religious affiliations can also be valuable because devout spirituality can be a deterrent to suicide behaviors.10 For an individual whose attempt was motivated by loneliness or feeling unloved or underappreciated, a newly realized support network can be an additional protective deterrent.

9. Does the patient have a family history of suicide?

There may be a familial component to suicide. Knowing about any suicide history in the family contributes to future therapeutic planning. The clinician may want to explore the patient’s family suicide history in detail because such information can have substantial impact on the patient’s motivation for attempting suicide. The evaluator may want to determine if the anniversary of a family suicide is coming. Triggers for a suicide attempt could include the anniversary of a death, birthdays, family-oriented holidays, and similar events. It is productive to understand how the patient feels about family members who have died by suicide. Some will empathize with the deceased, commenting that they did the “right thing.” Others, upon realizing how their own attempt affected others, will be remorseful and determined not to inflict more pain on their family. Such patients may need to be reminded of the misery associated with their family being left without them. These understandings are helpful at setting a safe disposition. However, a history of death by suicide in the family should always be thoroughly evaluated, regardless of the patient’s attitude about that death.

Continue to: Was the attempt the result of depression?

10. Was the attempt the result of depression?

For a patient experiencing depressive symptoms, the prognosis is less positive; they are more likely to harbor serious intent, premeditation, hopelessness, and social isolation, and less likely to express future-oriented thought. They often exhibit a temporary “flight into health.” Such progress is often transitory and may not represent recovery. Because mood disorders may still be present despite a temporary improvement, inpatient and pharmacologic treatment may be needed. If a patient’s suicide attempt occurred as a result of severe depression, it is possible they will make another suicide attempt unless their depression is addressed in a safe and secure setting, such as inpatient hospitalization, or through close family observation while the patient is receiving intensive outpatient treatment.

11. Does the patient have a psychotic disorder?

Many patients with a psychotic illness die following their first attempt without ever having contact with a mental health professional.11 Features of psychosis might include malevolent auditory hallucinations that suggest self-destruction.11 Such “voices” can be intense and self-deprecating; many patients with this type of hallucination report having made a suicide attempt “just to make the voices stop.”

Symptoms of paranoia can make it less likely for individuals with psychosis to confide in family members, friends, or medical personnel. Religious elements are often of a delusional nature and can be dangerous. Psychosis is more difficult to hide than depression and the presence of psychoses concurrent with major depressive disorder (MDD) increases the probability of suicidality.11 Psychosis secondary to substance use may diminish inhibitions and heighten impulsivity, thereby exacerbating the likelihood of self-harm. Usually, the presence of psychotic features precipitating or following a suicide attempt leads to psychiatric hospitalization.

12. Is the patient in a high-risk demographic group?

When evaluating a patient who has attempted suicide, it helps to consider not just what they did, but who they are. Specifically, does the individual belong to a demographic group that traditionally has a high rate of suicide? For example, patients who are Native American or Alaska Natives warrant extra caution.2 Older White males, especially those who are divorced, widowed, retired, and/or have chronic health problems, are also at greater risk. Compared to the general population, individuals age >80 have a massively elevated chance for self-induced death.12 Some of the reasons include:

- medical comorbidities make surviving an attempt less likely

- access to large amounts of medications

- more irreversible issues, such as chronic pain, disability, or widowhood

- living alone, which may delay discovery.

Patients who are members of any of these demographic groups may deserve serious consideration for inpatient psychiatric admission, regardless of other factors.

Continue to: Were drugs or alcohol involved?

13. Were drugs or alcohol involved?

This factor is unique in that it is both a chronic risk factor (SUDs) and a warning sign for imminent suicide, as in the case of an individual who gets intoxicated to disinhibit their fear of death so they can attempt suicide. Alcohol use disorders are associated with depression and suicide. Overdoses by fentanyl and other opiates have become more frequent.13 In many cases, fatalities are unintentional because users overestimate their tolerance or ingest contaminated substances.14 Disinhibition by alcohol and/or other drugs is a risk factor for attempting suicide and can intensify the depth of MDD. Some patients will ingest substances before an attempt just to give them the courage to act; many think of suicide only when intoxicated. Toxicology screens are indicated as part of the evaluation after a suicide attempt.

Depressive and suicidal thoughts often occur in people “coming down” from cocaine or other stimulants. These circumstances require determining whether to refer the patient for treatment for an SUD or psychiatric hospitalization.

In summary, getting intoxicated solely to diminish anxiety about suicide is a dangerous feature, whereas attempting suicide due to intoxication is less concerning. The latter patient may not consider suicide unless they become intoxicated again. When available, dual diagnosis treatment facilities can be an appropriate referral for such patients. Emergency department holding beds can allow these individuals to detoxify prior to the evaluation.

14. Does the patient have future-oriented thoughts?

When evaluating a patient who has attempted suicide, the presence of future planning and anticipation can be reassuring, but these features should be carefully assessed.14-16

After-the-fact comments may be more reliable when a patient offers them spontaneously, as opposed to in response to direct questioning.

- the specificity of the future plans

- corroboration from the family and others about the patient’s previous investment in the upcoming event

- whether the patient mentions such plans spontaneously or only in response to direct questioning

- the patient’s emotional expression or affect when discussing their future

- whether such plans are reasonable, grandiose, and/or unrealistic.

Bottom Line

When assessing a patient after a suicide attempt, both the patient’s presentation and history and the clinician’s instincts are important. Careful consideration of the method, stated intent, premeditation vs impulsivity, feelings about having survived, presence of psychiatric illness, high-risk demographic, postattempt demeanor and affect, quality of support, presence of self-rescue behaviors, future-oriented thoughts, and other factors can help in making the appropriate disposition.

Related Resources

- Kim H, Kim Y, Shin MH, et al. Early psychiatric referral after attempted suicide helps prevent suicide reattempts: a longitudinal national cohort study in South Korea. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:607892. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.607892

- Michaud L, Berva S, Ostertag L, et al. When to discharge and when to voluntary or compulsory hospitalize? Factors associated with treatment decision after self-harm. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114810. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114810

In 2021, suicide was the 11th leading cause of death in the United States.1 Suicide resulted in 49,000 US deaths during 2021; it was the second most common cause of death in individuals age 10 to 34, and the fifth leading cause among children.1,2 Women are 3 to 4 times more likely than men to attempt suicide, but men are 4 times more likely to die by suicide.2

The evaluation of patients with suicidal ideation who have not made an attempt generally involves assessing 4 factors: the specific plan, access to lethal means, any recent social stressors, and the presence of a psychiatric disorder.3 The clinician should also assess which potential deterrents, such as religious beliefs or dependent children, might be present.

Mental health clinicians are often called upon to evaluate a patient after a suicide attempt to assess intent for continued self-harm and to determine appropriate disposition. Such an evaluation must consider multiple factors, including the method used, premeditation, consequences of the attempt, the presence of severe depression and/or psychosis, and the role of substance use. Assessment after a suicide attempt differs from the examination of individuals who harbor suicidal thoughts but have not made an attempt; the latter group may be more likely to respond to interventions such as intensive outpatient care, mobilization of family support, and religious proscriptions against suicide. However, for patients who make an attempt to end their life, whatever potential safeguards or deterrents to suicide that were in place obviously did not prevent the self-harm act. The consequences of the attempt, such as disabling injuries or medical complications, and possible involuntary commitment, need to be considered. Assessment of the patient’s feelings about having survived the attempt is important because the psychological impact of the attempt on family members may serve to intensify the patient’s depression and make a subsequent attempt more likely.

Many individuals who think of suicide have communicated self-harm thoughts or intentions, but such comments are often minimized or ignored. There is a common but erroneous belief that if patients are encouraged to discuss thoughts of self-harm, they will be more likely to act upon them. Because the opposite is true,4 clinicians should ask vulnerable patients about suicidal ideation or intent. Importantly, noncompliance with life-saving medical care, risk-taking behaviors, and substance use may also signal a desire for self-harm. Passive thoughts of death, typified by comments such as “I don’t care whether I wake up or not,” should also be elicited. Many patients who think of suicide speak of being in a “bad place” where reason and logic give way to an intense desire to end their misery.

The evaluation of a patient who has attempted suicide is an important component of providing psychiatric care. This article reflects our 45 years of evaluating such patients. As such, it reflects our clinical experience and is not evidence-based. We offer a checklist of 14 questions that we have found helpful when determining if it would be best for a patient to receive inpatient psychiatric hospitalization or a discharge referral for outpatient care (Table). Questions 1 through 6 are specific for patients who have made a suicide attempt, while questions 7 through 14 are helpful for assessing global risk factors for suicide.

1. Was the attempt premeditated?

Determining premeditation vs impulsivity is an essential element of the assessment following a suicide attempt. Many such acts may occur without forethought in response to an unexpected stressor, such as an altercation between partners or family conflicts. Impulsive attempts can occur when an individual is involved in a distressing event and/or while intoxicated. Conversely, premeditation involves forethought and planning, which may increase the risk of suicide in the near future.

Examples of premeditated behavior include:

- Contemplating the attempt days or weeks beforehand

- Researching the effects of a medication or combination of medications in terms of potential lethality

- Engaging in behavior that would decrease the likelihood of their body being discovered after the attempt

- Obtaining weapons and/or stockpiling pills

- Canvassing potential sites such as bridges or tall buildings

- Engaging in a suicide attempt “practice run”

- Leaving a suicide note or message on social media

- Making funeral arrangements, such as choosing burial clothing

- Writing a will and arranging for the custody of dependent children

- Purchasing life insurance that does not deny payment of benefits in cases of death by suicide.

Continue to: Patients with a premeditated...

Patients with a premeditated suicide attempt generally do not expect to survive and are often surprised or upset that the act was not fatal. The presence of indicators that the attempt was premeditated should direct the disposition more toward hospitalization than discharge. In assessing the impact of premeditation, it is important to gauge not just the examples listed above, but also the patient’s perception of these issues (such as potential loss of child custody). Consider how much the patient is emotionally affected by such thinking.

2. What were the consequences of the attempt?

Assessing the reason for the attempt (if any) and determining whether the inciting circumstance has changed due to the suicide attempt are an important part of the evaluation. A suicide attempt may result in reconciliation with and/or renewed support from family members or partners, who might not have been aware of the patient’s emotional distress. Such unexpected support often results in the patient exhibiting improved mood and affect, and possibly temporary resolution of suicidal thoughts. This “flight into health” may be short-lived, but it also may be enough to engage the patient in a therapeutic alliance. That may permit a discharge with safe disposition to the outpatient clinic while in the custody of a family member, partner, or close friend.

Alternatively, some people experience a troubling worsening of precipitants following a suicide attempt. Preexisting medical conditions and financial, occupational, and/or social woes may be exacerbated. Child custody determinations may be affected, assuming the patient understands the possibility of this adverse consequence. Violent methods may result in disfigurement and body image issues. Individuals from small, close-knit communities may experience stigmatization and unwanted notoriety because of their suicide attempt. Such negative consequences may render some patients more likely to make another attempt to die by suicide. It is crucial to consider how a suicide attempt may have changed the original stress that led to the attempt.

3. Which method was used?

Most fatal suicides in the US are by firearms, and many individuals who survive such attempts do so because of unfamiliarity with the weapon, gun malfunction, faulty aim, or alcohol use.5-7 Some survivors report intending to shoot themselves in the heart, but instead suffered shoulder injuries. Unfortunately, for a patient who survives self-inflicted gunshot wounds, the sequelae of chronic pain, multiple surgical procedures, disability, and disfigurement may serve as constant negative reminders of the event. Some individuals with suicidal intent eschew the idea of using firearms because they hope to avoid having a family member be the first to discover them. Witnessing the aftermath of a fatal suicide by gunshot can induce symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in family members and/or partners.8

For a patient with self-inflicted gunshot wounds, always determine whether the weapon has been secured or if the patient still has access to it. Asking about weapon availability is essential during the evaluation of any patient with depression, major life crises, or other factors that may yield a desire to die; this is especially true for individuals with substance use disorders (SUDs). Whenever readily available to such individuals, weapons need to be safely removed.

Continue to: Other self-harm methods...

Other self-harm methods with a high degree of lethality include jumping from bridges or buildings, poisonings, self-immolation, cutting, and hangings. Individuals who choose these approaches generally do not intend to survive. Many of these methods also entail premeditation, as in the case of individuals who canvass bridges and note time when traffic is light so they are less likely to be interrupted. Between 1937 and 2012, there were >1,600 deaths by suicide from San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge.9 Patients who choose highly lethal methods are often irritated during the postattempt evaluation because their plans were not fatal. Usually, patients who choose such potentially lethal methods are hospitalized initially on medical and surgical floors, and receive most of their psychiatric care from consultation psychiatrists. Following discharge, these patients may be at high risk for subsequent suicide attempts.

In the US, the most common method of attempting suicide is by overdose.4 Lethality is determined by the agent or combination of substances ingested, the amount taken, the person’s health status, and the length of time before they are discovered. Many patients mistakenly assume that readily available agents such as acetaminophen and aspirin are less likely to be fatal than prescription medications. Evaluators may want to assess for suicidality in individuals with erratic, risk-taking behaviors, who are at especially high risk for death. Learning about the method the patient used can help the clinician determine the imminent risk of another suicide attempt. The more potentially fatal the patient’s method, the more serious their suicide intent, and the higher the risk they will make another suicide attempt, possibly using an even more lethal method.

4. What was the intent?

“What did you want to happen when you made this attempt?” Many patients will respond that they wanted to die, sleep, not wake up, or did not care what happened. Others say it was a gesture to evoke a certain response from another person. If this is the case, it is important to know whether the desired outcome was achieved. These so-called gestures often involve making sure the intended person is aware of the attempt, often by writing a letter, sending a text, or posting on social media. Such behaviors may be exhibited by patients with personality disorders. While such attempts often are impulsive, if the attempt fails to generate the anticipated effect, the patient may try to gain more attention by escalating their suicide actions.

Conversely, if a spouse or partner reconciles with the patient solely because of a suicide attempt, this may set a pattern for future self-harm events in which the patient hopes to achieve the same outcome. Nevertheless, it is better to err for safety because some of these patients will make another attempt, just to prove that they should have been taken more seriously. An exploration of such intent can help the evaluation because even supposed “gestures” can have dangerous consequences. Acts that do not result in the desired outcome should precipitate hospitalization rather than discharge.

5. What facilitated the patient’s rescue?

“Why is this patient still alive?” Determine if the patient did anything to save themself, such as calling an ambulance, inducing emesis, telling someone what they did, or coming to the hospital on their own. If yes, asking them what changed their mind may provide information about what exists in their lives to potentially prevent future attempts, or about wishes to stay alive. These issues can be used to guide outpatient therapy.

Continue to: How does the patient feel about having survived?

6. How does the patient feel about having survived?

When a patient is asked how they feel about having survived a suicide attempt, some will label their act “stupid” and profess embarrassment. Others exhibit future-oriented thought, which is a very good prognostic sign. More ominous is subsequent dysphoria or lamenting that “I could not even do this right.” Patients often express anger toward anyone who rescued them, especially those whose attempts were carefully planned or were discovered by accident. Some patients might also express ambivalence about having survived.

The patient’s response to this question may be shaped by their desire to avoid hospitalization, so beyond their verbal answers, be attentive to clinical cues that may suggest the patient is not being fully transparent. Anger or ambivalence about having survived, a lack of future-oriented thought, and a restricted affect despite verbalizing joy about still being alive are features that suggest psychiatric hospitalization may be warranted.

7. Has the patient made previous suicide attempts?

Compared to individuals with no previous suicide attempts, patients with a history of suicide attempts are 30 to 40 times more likely to die by suicide.2 Many patients who present after a suicide attempt have tried to kill themselves multiple times. Exploring the number of past attempts, how recent the attempts were, and what dispositions were made can be of benefit. Reviewing the potential lethality of past attempts (eg, was hospitalization required, was the patient placed in an intensive care unit, and/or was intubation needed) is recommended. If outpatient care was suggested or medication prescribed, was the patient adherent? Consider asking about passive suicidal behavior, such as not seeking care for medical issues, discontinuing life-saving medication, or engaging in reckless behavior. While such behaviors may not have been classified as a suicide attempt, it might indicate a feeling of indifference toward staying alive. A patient with a past attempt, especially if recent, merits consideration for inpatient care. Once again, referring previously nonadherent patients to outpatient treatment is less likely to be effective.

8. Does the patient have a support network?

Before discharging a patient who has made a suicide attempt, consider the quality of their support network. Gauging the response of the family and friends to the patient’s attempt can be beneficial. Indifference or resentment on the part of loved ones is a bad sign. Some patients have access to support networks they either did not know were available or chose not to utilize. In other instances, after realizing how depressed the patient has been, the family might provide a new safety net. Strong religious affiliations can also be valuable because devout spirituality can be a deterrent to suicide behaviors.10 For an individual whose attempt was motivated by loneliness or feeling unloved or underappreciated, a newly realized support network can be an additional protective deterrent.

9. Does the patient have a family history of suicide?

There may be a familial component to suicide. Knowing about any suicide history in the family contributes to future therapeutic planning. The clinician may want to explore the patient’s family suicide history in detail because such information can have substantial impact on the patient’s motivation for attempting suicide. The evaluator may want to determine if the anniversary of a family suicide is coming. Triggers for a suicide attempt could include the anniversary of a death, birthdays, family-oriented holidays, and similar events. It is productive to understand how the patient feels about family members who have died by suicide. Some will empathize with the deceased, commenting that they did the “right thing.” Others, upon realizing how their own attempt affected others, will be remorseful and determined not to inflict more pain on their family. Such patients may need to be reminded of the misery associated with their family being left without them. These understandings are helpful at setting a safe disposition. However, a history of death by suicide in the family should always be thoroughly evaluated, regardless of the patient’s attitude about that death.

Continue to: Was the attempt the result of depression?

10. Was the attempt the result of depression?

For a patient experiencing depressive symptoms, the prognosis is less positive; they are more likely to harbor serious intent, premeditation, hopelessness, and social isolation, and less likely to express future-oriented thought. They often exhibit a temporary “flight into health.” Such progress is often transitory and may not represent recovery. Because mood disorders may still be present despite a temporary improvement, inpatient and pharmacologic treatment may be needed. If a patient’s suicide attempt occurred as a result of severe depression, it is possible they will make another suicide attempt unless their depression is addressed in a safe and secure setting, such as inpatient hospitalization, or through close family observation while the patient is receiving intensive outpatient treatment.

11. Does the patient have a psychotic disorder?

Many patients with a psychotic illness die following their first attempt without ever having contact with a mental health professional.11 Features of psychosis might include malevolent auditory hallucinations that suggest self-destruction.11 Such “voices” can be intense and self-deprecating; many patients with this type of hallucination report having made a suicide attempt “just to make the voices stop.”

Symptoms of paranoia can make it less likely for individuals with psychosis to confide in family members, friends, or medical personnel. Religious elements are often of a delusional nature and can be dangerous. Psychosis is more difficult to hide than depression and the presence of psychoses concurrent with major depressive disorder (MDD) increases the probability of suicidality.11 Psychosis secondary to substance use may diminish inhibitions and heighten impulsivity, thereby exacerbating the likelihood of self-harm. Usually, the presence of psychotic features precipitating or following a suicide attempt leads to psychiatric hospitalization.

12. Is the patient in a high-risk demographic group?

When evaluating a patient who has attempted suicide, it helps to consider not just what they did, but who they are. Specifically, does the individual belong to a demographic group that traditionally has a high rate of suicide? For example, patients who are Native American or Alaska Natives warrant extra caution.2 Older White males, especially those who are divorced, widowed, retired, and/or have chronic health problems, are also at greater risk. Compared to the general population, individuals age >80 have a massively elevated chance for self-induced death.12 Some of the reasons include:

- medical comorbidities make surviving an attempt less likely

- access to large amounts of medications

- more irreversible issues, such as chronic pain, disability, or widowhood

- living alone, which may delay discovery.

Patients who are members of any of these demographic groups may deserve serious consideration for inpatient psychiatric admission, regardless of other factors.

Continue to: Were drugs or alcohol involved?

13. Were drugs or alcohol involved?

This factor is unique in that it is both a chronic risk factor (SUDs) and a warning sign for imminent suicide, as in the case of an individual who gets intoxicated to disinhibit their fear of death so they can attempt suicide. Alcohol use disorders are associated with depression and suicide. Overdoses by fentanyl and other opiates have become more frequent.13 In many cases, fatalities are unintentional because users overestimate their tolerance or ingest contaminated substances.14 Disinhibition by alcohol and/or other drugs is a risk factor for attempting suicide and can intensify the depth of MDD. Some patients will ingest substances before an attempt just to give them the courage to act; many think of suicide only when intoxicated. Toxicology screens are indicated as part of the evaluation after a suicide attempt.

Depressive and suicidal thoughts often occur in people “coming down” from cocaine or other stimulants. These circumstances require determining whether to refer the patient for treatment for an SUD or psychiatric hospitalization.

In summary, getting intoxicated solely to diminish anxiety about suicide is a dangerous feature, whereas attempting suicide due to intoxication is less concerning. The latter patient may not consider suicide unless they become intoxicated again. When available, dual diagnosis treatment facilities can be an appropriate referral for such patients. Emergency department holding beds can allow these individuals to detoxify prior to the evaluation.

14. Does the patient have future-oriented thoughts?

When evaluating a patient who has attempted suicide, the presence of future planning and anticipation can be reassuring, but these features should be carefully assessed.14-16

After-the-fact comments may be more reliable when a patient offers them spontaneously, as opposed to in response to direct questioning.

- the specificity of the future plans

- corroboration from the family and others about the patient’s previous investment in the upcoming event

- whether the patient mentions such plans spontaneously or only in response to direct questioning

- the patient’s emotional expression or affect when discussing their future

- whether such plans are reasonable, grandiose, and/or unrealistic.

Bottom Line

When assessing a patient after a suicide attempt, both the patient’s presentation and history and the clinician’s instincts are important. Careful consideration of the method, stated intent, premeditation vs impulsivity, feelings about having survived, presence of psychiatric illness, high-risk demographic, postattempt demeanor and affect, quality of support, presence of self-rescue behaviors, future-oriented thoughts, and other factors can help in making the appropriate disposition.

Related Resources

- Kim H, Kim Y, Shin MH, et al. Early psychiatric referral after attempted suicide helps prevent suicide reattempts: a longitudinal national cohort study in South Korea. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:607892. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.607892

- Michaud L, Berva S, Ostertag L, et al. When to discharge and when to voluntary or compulsory hospitalize? Factors associated with treatment decision after self-harm. Psychiatry Res. 2022;317:114810. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2022.114810

1. Ten Leading Causes of Death, United States 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention WISQARS. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://wisqars.cdc.gov/data/lcd/home

2. Norris D, Clark MS. Evaluation and treatment of suicidal patients. Am Fam Physician. 2012;15;85(6):602-605.

3. Gliatto MF, Rai AK. Evaluation and treatment patients with suicidal ideation. Am Fam Phys. 1999;59(6):1500-1506.

4. Dazzi T, Gribble R, Wessely S, et al. Does asking about suicide and related behaviors induce suicidal ideation? What is the evidence? Psychol Med. 2014;44(16):3361-3363.

5. Lewiecki EM, Miller SA. Suicide, guns and public policy. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(1):27-31.

6. Frierson RL. Women who shoot themselves. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1989;40(8):841-843.

7. Frierson RL, Lippmann SB. Psychiatric consultation for patients with self-inflicted gunshot wounds. Psychosomatics. 1990;31(1):67-74.

8. Mitchell AM, Terhorst L. PTSD symptoms in survivors bereaved by the suicide of a significant other. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2017;23(1):61-65.

9. Bateson J. The Golden Gate Bridge’s fatal flaw. Los Angeles Times. May 25, 2012. Accessed March 2, 2022. https://www.latimes.com/opinion/la-xpm-2012-may-25-la-oe-adv-bateson-golden-gate-20120525-story.html

10. Dervic K, Oquendoma MA, Grunebaum MF, et al. Religious affiliation and suicide attempt. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2303-2308.

11. Nordentoft H, Madsen T, Fedyszyn IF. Suicidal behavior and mortality in first episode psychosis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203(5):387-392.

12. Frierson R, Lippmann S. Suicide attempts by the old and the very old. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151(1):141-144.

13. Braden JB, Edlund MJ, Sullivan MD. Suicide deaths with opiate poisonings in the United States: 1999-2014. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(3):421-426.

14. Morin KA, Acharya S, Eibl JK, et al: Evidence of increased fentanyl use during the COVID-19 pandemic among opioid agonist treated patients in Ontario, Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;90:103088.

15. Shobassy A, Abu-Mohammad AS. Assessing imminent suicide risk: what about future planning? Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(2):12-17.

16. MacLeod AK, Pankhania B, Lee M, et al. Parasuicide, depression and the anticipation of positive and negative future experiences. Psychol Med. 1997;27(4):973-977.

17. Macleod AK, Tata P, Tyrer P, et al. Hopelessness and positive and negative future thinking in parasuicide. Br J Clin Psychol. 2010;44(Pt 4):495-504.

1. Ten Leading Causes of Death, United States 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention WISQARS. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://wisqars.cdc.gov/data/lcd/home

2. Norris D, Clark MS. Evaluation and treatment of suicidal patients. Am Fam Physician. 2012;15;85(6):602-605.

3. Gliatto MF, Rai AK. Evaluation and treatment patients with suicidal ideation. Am Fam Phys. 1999;59(6):1500-1506.

4. Dazzi T, Gribble R, Wessely S, et al. Does asking about suicide and related behaviors induce suicidal ideation? What is the evidence? Psychol Med. 2014;44(16):3361-3363.

5. Lewiecki EM, Miller SA. Suicide, guns and public policy. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(1):27-31.

6. Frierson RL. Women who shoot themselves. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1989;40(8):841-843.

7. Frierson RL, Lippmann SB. Psychiatric consultation for patients with self-inflicted gunshot wounds. Psychosomatics. 1990;31(1):67-74.

8. Mitchell AM, Terhorst L. PTSD symptoms in survivors bereaved by the suicide of a significant other. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2017;23(1):61-65.

9. Bateson J. The Golden Gate Bridge’s fatal flaw. Los Angeles Times. May 25, 2012. Accessed March 2, 2022. https://www.latimes.com/opinion/la-xpm-2012-may-25-la-oe-adv-bateson-golden-gate-20120525-story.html

10. Dervic K, Oquendoma MA, Grunebaum MF, et al. Religious affiliation and suicide attempt. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2303-2308.

11. Nordentoft H, Madsen T, Fedyszyn IF. Suicidal behavior and mortality in first episode psychosis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203(5):387-392.

12. Frierson R, Lippmann S. Suicide attempts by the old and the very old. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151(1):141-144.

13. Braden JB, Edlund MJ, Sullivan MD. Suicide deaths with opiate poisonings in the United States: 1999-2014. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(3):421-426.

14. Morin KA, Acharya S, Eibl JK, et al: Evidence of increased fentanyl use during the COVID-19 pandemic among opioid agonist treated patients in Ontario, Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;90:103088.

15. Shobassy A, Abu-Mohammad AS. Assessing imminent suicide risk: what about future planning? Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(2):12-17.

16. MacLeod AK, Pankhania B, Lee M, et al. Parasuicide, depression and the anticipation of positive and negative future experiences. Psychol Med. 1997;27(4):973-977.

17. Macleod AK, Tata P, Tyrer P, et al. Hopelessness and positive and negative future thinking in parasuicide. Br J Clin Psychol. 2010;44(Pt 4):495-504.

Let’s apply the lessons from the AIDS crisis to the COVID-19 pandemic

In 2020, COVID-19 disrupted our medical system, and life in general. In the 1980s, the AIDS epidemic devastated communities and overwhelmed hospitals. There were lessons learned from the AIDS epidemic that can be applied to the current situation.

Patients with HIV-spectrum illness faced stigmatization and societal indifference, including rejection by family members, increased rates of suicide, fears of sexual and/or intrauterine transmission, substance abuse issues, and alterations of body image for those with wasting syndromes and disfiguring Kaposi lesions. AIDS prevention strategies such as the provision of condoms and needle exchange programs were controversial, and many caregivers exposed to contaminated fluids had to endure months of antiretroviral treatment.

Similar to the AIDS epidemic, the COVID-19 pandemic has had significant psychological implications for patients and caregivers. Patients with COVID-19 infections also face feelings of guilt over potentially exposing a family member to the virus; devastating socioeconomic issues; restrictive hospital visitation policies for family members; disease news oversaturation; and feelings of hopelessness. People with AIDS in the 1980s faced the possibility of dying alone, and there was initial skepticism about medications to treat HIV—just as some individuals are now uneasy about recently introduced coronavirus vaccines.

The similarities of both diseases allow us some foresight on how to deal with current COVID-19 issues. Looking back on the AIDS epidemic should teach us to prioritize attending to the mental health of sufferers and caregivers, creating advocacy and support groups for when a patient’s family is unavailable, instilling public confidence in treatment options, maintaining staff morale, addressing substance abuse (due to COVID-related stress), and depoliticizing prevention strategies. Addressing these issues is especially critical for minority populations.

As respected medical care leaders, we can provide and draw extra attention to the needs of patients’ family members and health care personnel during this COVID-19 pandemic. Hopefully, the distribution of vaccines will shorten some of our communal and professional distress.

Robert Frierson, MD

Steven Lippmann, MD

Louisville, KY

In 2020, COVID-19 disrupted our medical system, and life in general. In the 1980s, the AIDS epidemic devastated communities and overwhelmed hospitals. There were lessons learned from the AIDS epidemic that can be applied to the current situation.

Patients with HIV-spectrum illness faced stigmatization and societal indifference, including rejection by family members, increased rates of suicide, fears of sexual and/or intrauterine transmission, substance abuse issues, and alterations of body image for those with wasting syndromes and disfiguring Kaposi lesions. AIDS prevention strategies such as the provision of condoms and needle exchange programs were controversial, and many caregivers exposed to contaminated fluids had to endure months of antiretroviral treatment.