User login

What is the best nonsurgical therapy for pelvic organ prolapse?

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) and pessaries are equally effective in treating symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse (POP). PFMT transiently improves patient satisfaction and reduces urinary incontinence more than pessaries do (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, a randomized controlled trial [RCT]).

PFMT moderately improves prolapse symptoms and severity, especially following 6 months of supervised intervention (SOR: B, a systematic review of randomized trials with some methodologic flaws).

Two pessaries (ring with support and Gellhorn) reduce symptoms in as many as 60% of patients (SOR: B, a systematic review of randomized trials).

Untreated postmenopausal women with mild grades of uterine prolapse are unlikely to develop more severe prolapse; 25% to 50% improve spontaneously (SOR: C, a prospective cohort study with methodologic flaws).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2010 multicenter RCT with 445 women (mean age 49.8 years) compared PFMT, pessary use, and combined treatment.1 Investigators used the Patient Global Impression of Improvement and the stress incontinence subscale of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory to measure patient satisfaction and urinary incontinence symptoms.

At 3 months, equivalent numbers of women using PFMT and a pessary (49% and 40%, respectively; P=.09) reported they were “much better” or “very much better.” More women in the PFMT cohort than women using a pessary reported resolution of incontinence symptoms at 3 months (49% vs 33%; P=.006), and satisfaction with treatment (75% vs 63%; P=.02), but these differences disappeared at 12 months. Combination therapy wasn’t superior to PFMT alone.

Pelvic floor muscle training improves symptoms, especially with perseverance

A 2011 Cochrane review that compared women receiving PFMT with a control group (observed but not treated) found that PFMT moderately improved prolapse symptoms and severity, especially following 6 months of supervised intervention.2 Investigators evalu-ated 4 trials, (N=857), including 3 with fewer than 25 women per arm.

Three studies found that PFMT improved symptom severity and manometric measures. Although the authors couldn’t pool the data because of different symptom scoring instruments, typical improvements ranged from 20% to 30%. Two trials found that PFMT increased the chance of improvement in POP stage by 17% (pooled data, relative risk=.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], .71-.96). PFMT also improved urinary outcomes (approximately 30% reduction in urinary frequency and stress incontinence symptoms) in 2 of 3 trials and improved bowel symptoms in one trial (approximately 25% to 30% reduction).

Pessaries also relieve symptoms

A 2013 Cochrane Review seeking to determine the effectiveness of pessaries in POP, identified one RCT (crossover, 3 month, multicenter, United States) that compared symptom relief and change in life impact over baseline for 134 women (parous, mean age 61 years, range 30-89 years) with POP stage II or greater who were treated with ring with support or Gellhorn pessaries.3 Sixty percent of patients who completed the study (the dropout rate was 37%) reported symptom relief with both types of pessary. Outcomes were measured by multiple questionnaires and Likert scales.

Patients reported improved symptoms on both the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory (POPDI) and Pelvic Organ Prolapse Impact Questionnaire (POPIQ) scales (P<.05 for difference from baseline on each scale, actual scores not reported). The ring with support and Gellhorn pessaries didn’t produce different scores on either scale (POPDI, P=.99; POPIQ, P=.29).

Untreated mild prolapse postmenopause usually doesn’t progress and may regress

A cohort of 412 postmenopausal women (ages ≥50 years) with POP who were observed, but not treated, found that mild POP was unlikely to progress and sometimes improved spontaneously.4 Over a mean follow-up of 5.7 years, few women with grade 1 POP (prolapsed pelvic organs remaining within the vagina) progressed to grade 2 or 3 (probability of progression for women with cystoceles=.095, 95% CI, .07-.13; women with rectoceles=.135, 95% CI, .09-.19; and women with uterine prolapse=.019, 95% CI, .0005-.099).

Some women with grade 1 POP regressed to grade 0 (probability of regression for women with cystoceles=.235, 95% CI, .19- .28; women with rectoceles=.22, 95% CI, .16-.28; and women with uterine prolapse=.48, 95% CI, 0.34-.62). Women with grades 2 and 3 POP were less likely to regress to grade 0 (probability of regression for women with cystoceles=.093, 95% CI, .05-.14; women with rectoceles=.033, 95% CI, .011-.075; and women with uterine prolapse=0, 95% CI, 0-.37).

One flaw of this study was that the women received hormone replacement therapy, which the investigators didn’t evaluate independently. However, a 2010 Cochrane review (2 small trials, one meta-analysis) found insufficient data to determine whether hormone replacement therapy alters POP.5

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin on POP recommends the following:6

- Pessaries can be fitted in most women with prolapse, regardless of prolapse stage (equivalent to grade) or site of predominant prolapse.

- Pessary use should be considered before surgical intervention in women with symptomatic prolapse.

- Women with prolapse who are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic can be observed at regular intervals, unless new bothersome symptoms develop.

1. Richter HE, Burgio KL, Brubaker L, et al;Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Continence pessary compared with behavioral therapy or combined therapy for stress incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:609-617.

2. Hagen S, Stark D. Conservative prevention and management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:CD003882.

3. Bugge C, Adams EJ, Gopinath D, et al. Pessaries (mechanical devices) for pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD004010.

4. Handa VL, Garrett E, Hendrix S, et al. Progression and remission of pelvic organ prolapse: a longitudinal study of menopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:27-32.

5. Ismail SI, Bain C, Hagen S. Oestrogens for treatment or prevention of pelvic organ prolapse in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;9:CD007063.

6. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 85: Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:717-729.

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) and pessaries are equally effective in treating symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse (POP). PFMT transiently improves patient satisfaction and reduces urinary incontinence more than pessaries do (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, a randomized controlled trial [RCT]).

PFMT moderately improves prolapse symptoms and severity, especially following 6 months of supervised intervention (SOR: B, a systematic review of randomized trials with some methodologic flaws).

Two pessaries (ring with support and Gellhorn) reduce symptoms in as many as 60% of patients (SOR: B, a systematic review of randomized trials).

Untreated postmenopausal women with mild grades of uterine prolapse are unlikely to develop more severe prolapse; 25% to 50% improve spontaneously (SOR: C, a prospective cohort study with methodologic flaws).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2010 multicenter RCT with 445 women (mean age 49.8 years) compared PFMT, pessary use, and combined treatment.1 Investigators used the Patient Global Impression of Improvement and the stress incontinence subscale of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory to measure patient satisfaction and urinary incontinence symptoms.

At 3 months, equivalent numbers of women using PFMT and a pessary (49% and 40%, respectively; P=.09) reported they were “much better” or “very much better.” More women in the PFMT cohort than women using a pessary reported resolution of incontinence symptoms at 3 months (49% vs 33%; P=.006), and satisfaction with treatment (75% vs 63%; P=.02), but these differences disappeared at 12 months. Combination therapy wasn’t superior to PFMT alone.

Pelvic floor muscle training improves symptoms, especially with perseverance

A 2011 Cochrane review that compared women receiving PFMT with a control group (observed but not treated) found that PFMT moderately improved prolapse symptoms and severity, especially following 6 months of supervised intervention.2 Investigators evalu-ated 4 trials, (N=857), including 3 with fewer than 25 women per arm.

Three studies found that PFMT improved symptom severity and manometric measures. Although the authors couldn’t pool the data because of different symptom scoring instruments, typical improvements ranged from 20% to 30%. Two trials found that PFMT increased the chance of improvement in POP stage by 17% (pooled data, relative risk=.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], .71-.96). PFMT also improved urinary outcomes (approximately 30% reduction in urinary frequency and stress incontinence symptoms) in 2 of 3 trials and improved bowel symptoms in one trial (approximately 25% to 30% reduction).

Pessaries also relieve symptoms

A 2013 Cochrane Review seeking to determine the effectiveness of pessaries in POP, identified one RCT (crossover, 3 month, multicenter, United States) that compared symptom relief and change in life impact over baseline for 134 women (parous, mean age 61 years, range 30-89 years) with POP stage II or greater who were treated with ring with support or Gellhorn pessaries.3 Sixty percent of patients who completed the study (the dropout rate was 37%) reported symptom relief with both types of pessary. Outcomes were measured by multiple questionnaires and Likert scales.

Patients reported improved symptoms on both the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory (POPDI) and Pelvic Organ Prolapse Impact Questionnaire (POPIQ) scales (P<.05 for difference from baseline on each scale, actual scores not reported). The ring with support and Gellhorn pessaries didn’t produce different scores on either scale (POPDI, P=.99; POPIQ, P=.29).

Untreated mild prolapse postmenopause usually doesn’t progress and may regress

A cohort of 412 postmenopausal women (ages ≥50 years) with POP who were observed, but not treated, found that mild POP was unlikely to progress and sometimes improved spontaneously.4 Over a mean follow-up of 5.7 years, few women with grade 1 POP (prolapsed pelvic organs remaining within the vagina) progressed to grade 2 or 3 (probability of progression for women with cystoceles=.095, 95% CI, .07-.13; women with rectoceles=.135, 95% CI, .09-.19; and women with uterine prolapse=.019, 95% CI, .0005-.099).

Some women with grade 1 POP regressed to grade 0 (probability of regression for women with cystoceles=.235, 95% CI, .19- .28; women with rectoceles=.22, 95% CI, .16-.28; and women with uterine prolapse=.48, 95% CI, 0.34-.62). Women with grades 2 and 3 POP were less likely to regress to grade 0 (probability of regression for women with cystoceles=.093, 95% CI, .05-.14; women with rectoceles=.033, 95% CI, .011-.075; and women with uterine prolapse=0, 95% CI, 0-.37).

One flaw of this study was that the women received hormone replacement therapy, which the investigators didn’t evaluate independently. However, a 2010 Cochrane review (2 small trials, one meta-analysis) found insufficient data to determine whether hormone replacement therapy alters POP.5

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin on POP recommends the following:6

- Pessaries can be fitted in most women with prolapse, regardless of prolapse stage (equivalent to grade) or site of predominant prolapse.

- Pessary use should be considered before surgical intervention in women with symptomatic prolapse.

- Women with prolapse who are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic can be observed at regular intervals, unless new bothersome symptoms develop.

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) and pessaries are equally effective in treating symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse (POP). PFMT transiently improves patient satisfaction and reduces urinary incontinence more than pessaries do (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, a randomized controlled trial [RCT]).

PFMT moderately improves prolapse symptoms and severity, especially following 6 months of supervised intervention (SOR: B, a systematic review of randomized trials with some methodologic flaws).

Two pessaries (ring with support and Gellhorn) reduce symptoms in as many as 60% of patients (SOR: B, a systematic review of randomized trials).

Untreated postmenopausal women with mild grades of uterine prolapse are unlikely to develop more severe prolapse; 25% to 50% improve spontaneously (SOR: C, a prospective cohort study with methodologic flaws).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2010 multicenter RCT with 445 women (mean age 49.8 years) compared PFMT, pessary use, and combined treatment.1 Investigators used the Patient Global Impression of Improvement and the stress incontinence subscale of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory to measure patient satisfaction and urinary incontinence symptoms.

At 3 months, equivalent numbers of women using PFMT and a pessary (49% and 40%, respectively; P=.09) reported they were “much better” or “very much better.” More women in the PFMT cohort than women using a pessary reported resolution of incontinence symptoms at 3 months (49% vs 33%; P=.006), and satisfaction with treatment (75% vs 63%; P=.02), but these differences disappeared at 12 months. Combination therapy wasn’t superior to PFMT alone.

Pelvic floor muscle training improves symptoms, especially with perseverance

A 2011 Cochrane review that compared women receiving PFMT with a control group (observed but not treated) found that PFMT moderately improved prolapse symptoms and severity, especially following 6 months of supervised intervention.2 Investigators evalu-ated 4 trials, (N=857), including 3 with fewer than 25 women per arm.

Three studies found that PFMT improved symptom severity and manometric measures. Although the authors couldn’t pool the data because of different symptom scoring instruments, typical improvements ranged from 20% to 30%. Two trials found that PFMT increased the chance of improvement in POP stage by 17% (pooled data, relative risk=.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], .71-.96). PFMT also improved urinary outcomes (approximately 30% reduction in urinary frequency and stress incontinence symptoms) in 2 of 3 trials and improved bowel symptoms in one trial (approximately 25% to 30% reduction).

Pessaries also relieve symptoms

A 2013 Cochrane Review seeking to determine the effectiveness of pessaries in POP, identified one RCT (crossover, 3 month, multicenter, United States) that compared symptom relief and change in life impact over baseline for 134 women (parous, mean age 61 years, range 30-89 years) with POP stage II or greater who were treated with ring with support or Gellhorn pessaries.3 Sixty percent of patients who completed the study (the dropout rate was 37%) reported symptom relief with both types of pessary. Outcomes were measured by multiple questionnaires and Likert scales.

Patients reported improved symptoms on both the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory (POPDI) and Pelvic Organ Prolapse Impact Questionnaire (POPIQ) scales (P<.05 for difference from baseline on each scale, actual scores not reported). The ring with support and Gellhorn pessaries didn’t produce different scores on either scale (POPDI, P=.99; POPIQ, P=.29).

Untreated mild prolapse postmenopause usually doesn’t progress and may regress

A cohort of 412 postmenopausal women (ages ≥50 years) with POP who were observed, but not treated, found that mild POP was unlikely to progress and sometimes improved spontaneously.4 Over a mean follow-up of 5.7 years, few women with grade 1 POP (prolapsed pelvic organs remaining within the vagina) progressed to grade 2 or 3 (probability of progression for women with cystoceles=.095, 95% CI, .07-.13; women with rectoceles=.135, 95% CI, .09-.19; and women with uterine prolapse=.019, 95% CI, .0005-.099).

Some women with grade 1 POP regressed to grade 0 (probability of regression for women with cystoceles=.235, 95% CI, .19- .28; women with rectoceles=.22, 95% CI, .16-.28; and women with uterine prolapse=.48, 95% CI, 0.34-.62). Women with grades 2 and 3 POP were less likely to regress to grade 0 (probability of regression for women with cystoceles=.093, 95% CI, .05-.14; women with rectoceles=.033, 95% CI, .011-.075; and women with uterine prolapse=0, 95% CI, 0-.37).

One flaw of this study was that the women received hormone replacement therapy, which the investigators didn’t evaluate independently. However, a 2010 Cochrane review (2 small trials, one meta-analysis) found insufficient data to determine whether hormone replacement therapy alters POP.5

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin on POP recommends the following:6

- Pessaries can be fitted in most women with prolapse, regardless of prolapse stage (equivalent to grade) or site of predominant prolapse.

- Pessary use should be considered before surgical intervention in women with symptomatic prolapse.

- Women with prolapse who are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic can be observed at regular intervals, unless new bothersome symptoms develop.

1. Richter HE, Burgio KL, Brubaker L, et al;Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Continence pessary compared with behavioral therapy or combined therapy for stress incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:609-617.

2. Hagen S, Stark D. Conservative prevention and management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:CD003882.

3. Bugge C, Adams EJ, Gopinath D, et al. Pessaries (mechanical devices) for pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD004010.

4. Handa VL, Garrett E, Hendrix S, et al. Progression and remission of pelvic organ prolapse: a longitudinal study of menopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:27-32.

5. Ismail SI, Bain C, Hagen S. Oestrogens for treatment or prevention of pelvic organ prolapse in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;9:CD007063.

6. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 85: Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:717-729.

1. Richter HE, Burgio KL, Brubaker L, et al;Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Continence pessary compared with behavioral therapy or combined therapy for stress incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:609-617.

2. Hagen S, Stark D. Conservative prevention and management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:CD003882.

3. Bugge C, Adams EJ, Gopinath D, et al. Pessaries (mechanical devices) for pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD004010.

4. Handa VL, Garrett E, Hendrix S, et al. Progression and remission of pelvic organ prolapse: a longitudinal study of menopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:27-32.

5. Ismail SI, Bain C, Hagen S. Oestrogens for treatment or prevention of pelvic organ prolapse in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;9:CD007063.

6. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 85: Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:717-729.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Chronic urticaria: What diagnostic evaluation is best?

A DETAILED HISTORY AND 6-WEEK TRIAL of an H1 antihistamine are the best diagnostic evaluations for chronic urticaria. More extensive diagnostic work-up adds little, unless the patient’s history specifically indicates a need for further evaluation (strength of recommendation: B, inconsistent or limited-quality evidence).

Evidence summary

Chronic urticaria affects 1% of the general population and is usually defined as the presence of hives (with or without angioedema) for at least 6 weeks.1

History and physical are key, a few tests may be useful

A systematic review of 29 studies involving 6462 patients done between 1966 and 2001 found no strong evidence for laboratory testing beyond a complete history and physical. However, the authors recommended that patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria have an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) measurement, white blood cell (WBC) count, and differential cell count.2 A primarily expert-opinion-based guideline on chronic urticaria recommended a WBC count, ESR, urinalysis, and liver function tests to screen for underlying diseases.3

Is aggressive testing worth the effort?

It would appear not. A prospective study of 220 patients, representative of the studies included in the systematic review, compared 2 strategies to evaluate the cause of chronic urticaria:

- Detailed history taking and limited laboratory testing (hemoglobin, hematocrit, ESR, WBC count, and dermatographism test [hive associated with a scratch])

- Detailed history taking and extensive laboratory evaluation with 33 different tests, many of them special and invasive (radiographs, vaginal cultures, and skin biopsies).4

Detailed history taking and limited laboratory tests found a cause for urticaria in 45.9% of patients, compared with 52.7% of patients who underwent detailed history taking and extensive laboratory screening.4 This translates into testing 15 patients aggressively to diagnose one potentially reversible cause of chronic urticaria.

Among patients evaluated with a detailed history and extensive diagnostic work-up, 33.2% had physical urticaria (triggered by pressure, cold, heat, and light). Other diagnoses included adverse drug reactions (8.6%), adverse food reactions (6.8%), infection (1.8%), contact urticaria (0.9%), and internal disease (1.4%). No cause was identified in 47.3% of the patients.4

Recommendations

The British Association of Dermatologists has issued the following guidelines for evaluation and management of urticaria in adults and children:5

- The diagnosis of urticaria is primarily clinical.

- Diagnostic investigations should be guided by the history and shouldn’t be performed in all patients.

Acknowledgements

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and should not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the US Air Force Medical Service or the US Air Force at large.

1. Tedeschi A, Girolomoni G, Asero R. AAITO Committee for Chronic Urticaria and Pruritus Guidelines. AAITO position paper. Chronic urticaria: diagnostic workup and treatment. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;39:225-231.

2. Kozel MM, Bossuyt PM, Mekkes JR, et al. Laboratory tests and identified diagnosis in patients with physical and chronic urticaria and angioedema: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:409-416.

3. Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters. The diagnosis and management of urticaria: a practice parameter, part I: acute urticaria/angioedema; part II: chronic urticaria/angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:521-544.

4. Kozel MM, Mekkes JR, Bossuyt PM, et al. The effectiveness of a history-based diagnostic approach in chronic urticaria and angioedema. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1575-1580.

5. Grattan CE, Humphreys F. British Association of Dermatologists Therapy Guidelines and Audit Subcommittee. Guidelines for evaluation and management of urticaria in adults and children. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1116-1123.

A DETAILED HISTORY AND 6-WEEK TRIAL of an H1 antihistamine are the best diagnostic evaluations for chronic urticaria. More extensive diagnostic work-up adds little, unless the patient’s history specifically indicates a need for further evaluation (strength of recommendation: B, inconsistent or limited-quality evidence).

Evidence summary

Chronic urticaria affects 1% of the general population and is usually defined as the presence of hives (with or without angioedema) for at least 6 weeks.1

History and physical are key, a few tests may be useful

A systematic review of 29 studies involving 6462 patients done between 1966 and 2001 found no strong evidence for laboratory testing beyond a complete history and physical. However, the authors recommended that patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria have an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) measurement, white blood cell (WBC) count, and differential cell count.2 A primarily expert-opinion-based guideline on chronic urticaria recommended a WBC count, ESR, urinalysis, and liver function tests to screen for underlying diseases.3

Is aggressive testing worth the effort?

It would appear not. A prospective study of 220 patients, representative of the studies included in the systematic review, compared 2 strategies to evaluate the cause of chronic urticaria:

- Detailed history taking and limited laboratory testing (hemoglobin, hematocrit, ESR, WBC count, and dermatographism test [hive associated with a scratch])

- Detailed history taking and extensive laboratory evaluation with 33 different tests, many of them special and invasive (radiographs, vaginal cultures, and skin biopsies).4

Detailed history taking and limited laboratory tests found a cause for urticaria in 45.9% of patients, compared with 52.7% of patients who underwent detailed history taking and extensive laboratory screening.4 This translates into testing 15 patients aggressively to diagnose one potentially reversible cause of chronic urticaria.

Among patients evaluated with a detailed history and extensive diagnostic work-up, 33.2% had physical urticaria (triggered by pressure, cold, heat, and light). Other diagnoses included adverse drug reactions (8.6%), adverse food reactions (6.8%), infection (1.8%), contact urticaria (0.9%), and internal disease (1.4%). No cause was identified in 47.3% of the patients.4

Recommendations

The British Association of Dermatologists has issued the following guidelines for evaluation and management of urticaria in adults and children:5

- The diagnosis of urticaria is primarily clinical.

- Diagnostic investigations should be guided by the history and shouldn’t be performed in all patients.

Acknowledgements

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and should not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the US Air Force Medical Service or the US Air Force at large.

A DETAILED HISTORY AND 6-WEEK TRIAL of an H1 antihistamine are the best diagnostic evaluations for chronic urticaria. More extensive diagnostic work-up adds little, unless the patient’s history specifically indicates a need for further evaluation (strength of recommendation: B, inconsistent or limited-quality evidence).

Evidence summary

Chronic urticaria affects 1% of the general population and is usually defined as the presence of hives (with or without angioedema) for at least 6 weeks.1

History and physical are key, a few tests may be useful

A systematic review of 29 studies involving 6462 patients done between 1966 and 2001 found no strong evidence for laboratory testing beyond a complete history and physical. However, the authors recommended that patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria have an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) measurement, white blood cell (WBC) count, and differential cell count.2 A primarily expert-opinion-based guideline on chronic urticaria recommended a WBC count, ESR, urinalysis, and liver function tests to screen for underlying diseases.3

Is aggressive testing worth the effort?

It would appear not. A prospective study of 220 patients, representative of the studies included in the systematic review, compared 2 strategies to evaluate the cause of chronic urticaria:

- Detailed history taking and limited laboratory testing (hemoglobin, hematocrit, ESR, WBC count, and dermatographism test [hive associated with a scratch])

- Detailed history taking and extensive laboratory evaluation with 33 different tests, many of them special and invasive (radiographs, vaginal cultures, and skin biopsies).4

Detailed history taking and limited laboratory tests found a cause for urticaria in 45.9% of patients, compared with 52.7% of patients who underwent detailed history taking and extensive laboratory screening.4 This translates into testing 15 patients aggressively to diagnose one potentially reversible cause of chronic urticaria.

Among patients evaluated with a detailed history and extensive diagnostic work-up, 33.2% had physical urticaria (triggered by pressure, cold, heat, and light). Other diagnoses included adverse drug reactions (8.6%), adverse food reactions (6.8%), infection (1.8%), contact urticaria (0.9%), and internal disease (1.4%). No cause was identified in 47.3% of the patients.4

Recommendations

The British Association of Dermatologists has issued the following guidelines for evaluation and management of urticaria in adults and children:5

- The diagnosis of urticaria is primarily clinical.

- Diagnostic investigations should be guided by the history and shouldn’t be performed in all patients.

Acknowledgements

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and should not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the US Air Force Medical Service or the US Air Force at large.

1. Tedeschi A, Girolomoni G, Asero R. AAITO Committee for Chronic Urticaria and Pruritus Guidelines. AAITO position paper. Chronic urticaria: diagnostic workup and treatment. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;39:225-231.

2. Kozel MM, Bossuyt PM, Mekkes JR, et al. Laboratory tests and identified diagnosis in patients with physical and chronic urticaria and angioedema: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:409-416.

3. Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters. The diagnosis and management of urticaria: a practice parameter, part I: acute urticaria/angioedema; part II: chronic urticaria/angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:521-544.

4. Kozel MM, Mekkes JR, Bossuyt PM, et al. The effectiveness of a history-based diagnostic approach in chronic urticaria and angioedema. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1575-1580.

5. Grattan CE, Humphreys F. British Association of Dermatologists Therapy Guidelines and Audit Subcommittee. Guidelines for evaluation and management of urticaria in adults and children. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1116-1123.

1. Tedeschi A, Girolomoni G, Asero R. AAITO Committee for Chronic Urticaria and Pruritus Guidelines. AAITO position paper. Chronic urticaria: diagnostic workup and treatment. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;39:225-231.

2. Kozel MM, Bossuyt PM, Mekkes JR, et al. Laboratory tests and identified diagnosis in patients with physical and chronic urticaria and angioedema: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:409-416.

3. Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters. The diagnosis and management of urticaria: a practice parameter, part I: acute urticaria/angioedema; part II: chronic urticaria/angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:521-544.

4. Kozel MM, Mekkes JR, Bossuyt PM, et al. The effectiveness of a history-based diagnostic approach in chronic urticaria and angioedema. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1575-1580.

5. Grattan CE, Humphreys F. British Association of Dermatologists Therapy Guidelines and Audit Subcommittee. Guidelines for evaluation and management of urticaria in adults and children. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1116-1123.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

What is the best way to manage phantom limb pain?

No single best therapy for phantom limb pain (PLP) exists. Treatment requires a coordinated application of conservative, pharmacologic, and adjuvant therapies.

Evaluative management (including prosthesis adjustment, treatment of referred pain, and residual limb care) should be tried initially (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C, expert opinion). Other first-line treatments such as transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) (SOR: A, multiple high-quality randomized, control trials [RCTs]), and biofeedback (SOR: B, numerous case studies) can reduce PLP. Pharmacotherapy, including opioids, anticonvulsants (gabapentin), and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), can also relieve pain (SOR: B, initial RCTs and inconsistent findings).

Adjuvant therapies (mirror box therapy, acupuncture, calcitonin, and N-methyl d-aspartate receptor antagonists) haven’t been rigorously investigated for alleviating PLP, but can be considered for patients who have failed other treatments.

Evidence summary

An estimated 1.7 million people in the United States are living with limb loss. The number is expected to increase because of ongoing military conflicts.1 The incidence of PLP is 60% to 80% among amputees.1

A multidisciplinary approach

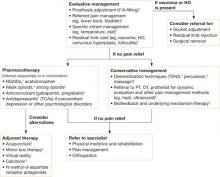

A lack of comparative clinical trials of therapies for PLP has led health-care providers to adopt a multidisciplinary approach that combines evaluative management, desensitization, psychotherapy, and pharmacotherapy (FIGURE).

Evaluative management, based largely on expert opinion, includes assessing the fit of the prosthesis, treating referred pain, and assessing aggravating factors. Because residual limb pain can exacerbate PLP, adjusting a poorly fitting prosthesis or providing the patient with NSAIDs when there is evidence of stump inflammation may adequately control pain.2,3 Anatomically distant pain syndromes, such as hip or lower back pain, can also aggravate PLP and should be managed to provide optimal pain relief.2

Desensitization, using TENS, has reduced PLP in multiple placebo-controlled trials and epidemiologic surveys.2-5 TENS is an easy-to-use, low-cost, noninvasive, first-line therapy.5 Its long-term effectiveness in alleviating PLP remains unknown.2 Some experts suggest that pain reductions after 1 year of treatment are comparable to placebo.2 Other forms of desensitization (percussion and massage) are supported only by anecdotal reports.

Psychotherapy, including biofeedback, has been found in several case studies to effectively treat chronic PLP.2,5 Psychotherapy can reportedly reveal the underlying mechanisms (muscle spasm, vascular insufficiency) and therefore direct therapeutic interventions by biofeedback or other focus techniques.2

FIGURE Management of phantom limb pain1-10

*Expert opinion.

†Case studies.

‡Randomized controlled trials or cohort studies.

Pharmacotherapy is best used as an adjunct to other treatments.2 Although PLP is typically treated as neuropathic pain, only a few medications have been critically evaluated for treating it.6 Morphine (number needed to treat [NNT]=2.5; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.9-3.4) and other opioids, including tramadol (NNT=3.9; 95% CI, 2.7-6.7 in neuropathic pain) help some patients.6,7 Despite the proven benefit of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) in other neuropathic pain conditions, a recent RCT demonstrated no benefit of TCAs over placebo in PLP.8 Anticonvulsants, including gabapentin, have documented benefit in neuropathic pain modalities and are often used for PLP.6 However, their value in reducing PLP is still under investigation.6 One 2002 RCT showed benefit regarding an improvement of the visual analog scale by an average of 3 points (on a 10-point scale) after 6 weeks of gabapentin therapy.9 A similarly designed 2006 RCT of gabapentin, however did not identify significant pain reductions.10

Promising adjuvant therapies use mirroring techniques

Of the adjuvant treatments mentioned previously, only mirror box therapy has shown promise. This technique allows the amputee to perceive the missing limb by focusing on the reflection of the remaining limb during specific movements and activities. Theoretically, this perception allows reconfiguration of the amputee’s sensory cortex.

Virtual reality therapy employs similar techniques based on the idea that the brain can be deceived. Initial case studies are promising and have prompted further research.11

Recommendations

The US Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense recently issued clinical guidelines for rehabilitating lower-limb amputees that include a segment on pain management.12 The guidelines stress the importance of an interdisciplinary team approach that addresses each pathology plaguing the amputee.

They recommend narcotics during the immediate postoperative period, followed by transition to a non-narcotic medical regimen during the rehabilitation process. The guidelines don’t support a single, specific pain control method over others; they recommend the following approaches to PLP:

- pharmacologic treatment, which may include antiseizure medications, tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, NSAIDs, dextromethorathane, or long-acting narcotics

- epidural analgesia, patient-controlled analgesia, or regional analgesia

- nonpharmacologic therapies, including TENS, desensitization, scar mobilization, relaxation, and biofeedback.

Acknowledgements

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and not to be construed as official, or as reflecting the views of the US Air Force Medical Service or the US Air Force at large.

1. Ziegler-Graham K, MacKenzie EI, Ephraim PL, et al. Estimating the prevalence of limb loss in the United States: 2005 to 2050. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:422-429.

2. Sherman RA. Postamputation pain. In: Jensen TS, Wilson PR, Rice AS, eds. Clinical Pain Management: Chronic Pain. London: Hodder Arnold Publishing; 2002;32:427-436.

3. Wartan SW, Hamann W, Wedley JR, et al. Phantom pain and sensation among British veteran amputees. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78:652-659.

4. Halbert J, Crotty M, Cameron ID. Evidence for the optimal management of acute and chronic phantom pain: a systematic review. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:84-92.

5. Baron R, Wasner G, Lindner V. Optimal treatment of phantom limb pain in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 1998;12:361-376.

6. Finnerup NB, Otto M, McQuay HJ, et al. Algorithm for neuropathic pain treatment: an evidence-based proposal. Pain. 2005;118:289-305.

7. Huse E, Larbig W, Flor H, et al. The effect of opioids on phantom limb pain and cortical reorganization. Pain. 2001;90:47-55.

8. Robinson LR, Czerniecki JM, Ehde DM, et al. Trial of amitriptyline for relief of pain in amputees: results of a randomized controlled study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1-6.

9. Bone M, Critchley P, Buggy DJ. Gabapentin in postamputation phantom limb pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2002;27:481-486.

10. Nikolajsen L, Finnerup NB, Kramp S, et al. A randomized study of the effects of gabapentin on post-amputation pain. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:1008-1015.

11. Chan BL, Witt R, Charrow AP, et al. Mirror therapy for phantom limb pain. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2206-2207.

12. Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for rehabilitation of lower amputation. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense; 2007:1-55. Available at: www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?doc_id=11758&nbr=006060&string=amputation. Accessed December 13, 2008.

No single best therapy for phantom limb pain (PLP) exists. Treatment requires a coordinated application of conservative, pharmacologic, and adjuvant therapies.

Evaluative management (including prosthesis adjustment, treatment of referred pain, and residual limb care) should be tried initially (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C, expert opinion). Other first-line treatments such as transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) (SOR: A, multiple high-quality randomized, control trials [RCTs]), and biofeedback (SOR: B, numerous case studies) can reduce PLP. Pharmacotherapy, including opioids, anticonvulsants (gabapentin), and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), can also relieve pain (SOR: B, initial RCTs and inconsistent findings).

Adjuvant therapies (mirror box therapy, acupuncture, calcitonin, and N-methyl d-aspartate receptor antagonists) haven’t been rigorously investigated for alleviating PLP, but can be considered for patients who have failed other treatments.

Evidence summary

An estimated 1.7 million people in the United States are living with limb loss. The number is expected to increase because of ongoing military conflicts.1 The incidence of PLP is 60% to 80% among amputees.1

A multidisciplinary approach

A lack of comparative clinical trials of therapies for PLP has led health-care providers to adopt a multidisciplinary approach that combines evaluative management, desensitization, psychotherapy, and pharmacotherapy (FIGURE).

Evaluative management, based largely on expert opinion, includes assessing the fit of the prosthesis, treating referred pain, and assessing aggravating factors. Because residual limb pain can exacerbate PLP, adjusting a poorly fitting prosthesis or providing the patient with NSAIDs when there is evidence of stump inflammation may adequately control pain.2,3 Anatomically distant pain syndromes, such as hip or lower back pain, can also aggravate PLP and should be managed to provide optimal pain relief.2

Desensitization, using TENS, has reduced PLP in multiple placebo-controlled trials and epidemiologic surveys.2-5 TENS is an easy-to-use, low-cost, noninvasive, first-line therapy.5 Its long-term effectiveness in alleviating PLP remains unknown.2 Some experts suggest that pain reductions after 1 year of treatment are comparable to placebo.2 Other forms of desensitization (percussion and massage) are supported only by anecdotal reports.

Psychotherapy, including biofeedback, has been found in several case studies to effectively treat chronic PLP.2,5 Psychotherapy can reportedly reveal the underlying mechanisms (muscle spasm, vascular insufficiency) and therefore direct therapeutic interventions by biofeedback or other focus techniques.2

FIGURE Management of phantom limb pain1-10

*Expert opinion.

†Case studies.

‡Randomized controlled trials or cohort studies.

Pharmacotherapy is best used as an adjunct to other treatments.2 Although PLP is typically treated as neuropathic pain, only a few medications have been critically evaluated for treating it.6 Morphine (number needed to treat [NNT]=2.5; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.9-3.4) and other opioids, including tramadol (NNT=3.9; 95% CI, 2.7-6.7 in neuropathic pain) help some patients.6,7 Despite the proven benefit of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) in other neuropathic pain conditions, a recent RCT demonstrated no benefit of TCAs over placebo in PLP.8 Anticonvulsants, including gabapentin, have documented benefit in neuropathic pain modalities and are often used for PLP.6 However, their value in reducing PLP is still under investigation.6 One 2002 RCT showed benefit regarding an improvement of the visual analog scale by an average of 3 points (on a 10-point scale) after 6 weeks of gabapentin therapy.9 A similarly designed 2006 RCT of gabapentin, however did not identify significant pain reductions.10

Promising adjuvant therapies use mirroring techniques

Of the adjuvant treatments mentioned previously, only mirror box therapy has shown promise. This technique allows the amputee to perceive the missing limb by focusing on the reflection of the remaining limb during specific movements and activities. Theoretically, this perception allows reconfiguration of the amputee’s sensory cortex.

Virtual reality therapy employs similar techniques based on the idea that the brain can be deceived. Initial case studies are promising and have prompted further research.11

Recommendations

The US Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense recently issued clinical guidelines for rehabilitating lower-limb amputees that include a segment on pain management.12 The guidelines stress the importance of an interdisciplinary team approach that addresses each pathology plaguing the amputee.

They recommend narcotics during the immediate postoperative period, followed by transition to a non-narcotic medical regimen during the rehabilitation process. The guidelines don’t support a single, specific pain control method over others; they recommend the following approaches to PLP:

- pharmacologic treatment, which may include antiseizure medications, tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, NSAIDs, dextromethorathane, or long-acting narcotics

- epidural analgesia, patient-controlled analgesia, or regional analgesia

- nonpharmacologic therapies, including TENS, desensitization, scar mobilization, relaxation, and biofeedback.

Acknowledgements

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and not to be construed as official, or as reflecting the views of the US Air Force Medical Service or the US Air Force at large.

No single best therapy for phantom limb pain (PLP) exists. Treatment requires a coordinated application of conservative, pharmacologic, and adjuvant therapies.

Evaluative management (including prosthesis adjustment, treatment of referred pain, and residual limb care) should be tried initially (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C, expert opinion). Other first-line treatments such as transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) (SOR: A, multiple high-quality randomized, control trials [RCTs]), and biofeedback (SOR: B, numerous case studies) can reduce PLP. Pharmacotherapy, including opioids, anticonvulsants (gabapentin), and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), can also relieve pain (SOR: B, initial RCTs and inconsistent findings).

Adjuvant therapies (mirror box therapy, acupuncture, calcitonin, and N-methyl d-aspartate receptor antagonists) haven’t been rigorously investigated for alleviating PLP, but can be considered for patients who have failed other treatments.

Evidence summary

An estimated 1.7 million people in the United States are living with limb loss. The number is expected to increase because of ongoing military conflicts.1 The incidence of PLP is 60% to 80% among amputees.1

A multidisciplinary approach

A lack of comparative clinical trials of therapies for PLP has led health-care providers to adopt a multidisciplinary approach that combines evaluative management, desensitization, psychotherapy, and pharmacotherapy (FIGURE).

Evaluative management, based largely on expert opinion, includes assessing the fit of the prosthesis, treating referred pain, and assessing aggravating factors. Because residual limb pain can exacerbate PLP, adjusting a poorly fitting prosthesis or providing the patient with NSAIDs when there is evidence of stump inflammation may adequately control pain.2,3 Anatomically distant pain syndromes, such as hip or lower back pain, can also aggravate PLP and should be managed to provide optimal pain relief.2

Desensitization, using TENS, has reduced PLP in multiple placebo-controlled trials and epidemiologic surveys.2-5 TENS is an easy-to-use, low-cost, noninvasive, first-line therapy.5 Its long-term effectiveness in alleviating PLP remains unknown.2 Some experts suggest that pain reductions after 1 year of treatment are comparable to placebo.2 Other forms of desensitization (percussion and massage) are supported only by anecdotal reports.

Psychotherapy, including biofeedback, has been found in several case studies to effectively treat chronic PLP.2,5 Psychotherapy can reportedly reveal the underlying mechanisms (muscle spasm, vascular insufficiency) and therefore direct therapeutic interventions by biofeedback or other focus techniques.2

FIGURE Management of phantom limb pain1-10

*Expert opinion.

†Case studies.

‡Randomized controlled trials or cohort studies.

Pharmacotherapy is best used as an adjunct to other treatments.2 Although PLP is typically treated as neuropathic pain, only a few medications have been critically evaluated for treating it.6 Morphine (number needed to treat [NNT]=2.5; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.9-3.4) and other opioids, including tramadol (NNT=3.9; 95% CI, 2.7-6.7 in neuropathic pain) help some patients.6,7 Despite the proven benefit of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) in other neuropathic pain conditions, a recent RCT demonstrated no benefit of TCAs over placebo in PLP.8 Anticonvulsants, including gabapentin, have documented benefit in neuropathic pain modalities and are often used for PLP.6 However, their value in reducing PLP is still under investigation.6 One 2002 RCT showed benefit regarding an improvement of the visual analog scale by an average of 3 points (on a 10-point scale) after 6 weeks of gabapentin therapy.9 A similarly designed 2006 RCT of gabapentin, however did not identify significant pain reductions.10

Promising adjuvant therapies use mirroring techniques

Of the adjuvant treatments mentioned previously, only mirror box therapy has shown promise. This technique allows the amputee to perceive the missing limb by focusing on the reflection of the remaining limb during specific movements and activities. Theoretically, this perception allows reconfiguration of the amputee’s sensory cortex.

Virtual reality therapy employs similar techniques based on the idea that the brain can be deceived. Initial case studies are promising and have prompted further research.11

Recommendations

The US Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense recently issued clinical guidelines for rehabilitating lower-limb amputees that include a segment on pain management.12 The guidelines stress the importance of an interdisciplinary team approach that addresses each pathology plaguing the amputee.

They recommend narcotics during the immediate postoperative period, followed by transition to a non-narcotic medical regimen during the rehabilitation process. The guidelines don’t support a single, specific pain control method over others; they recommend the following approaches to PLP:

- pharmacologic treatment, which may include antiseizure medications, tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, NSAIDs, dextromethorathane, or long-acting narcotics

- epidural analgesia, patient-controlled analgesia, or regional analgesia

- nonpharmacologic therapies, including TENS, desensitization, scar mobilization, relaxation, and biofeedback.

Acknowledgements

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and not to be construed as official, or as reflecting the views of the US Air Force Medical Service or the US Air Force at large.

1. Ziegler-Graham K, MacKenzie EI, Ephraim PL, et al. Estimating the prevalence of limb loss in the United States: 2005 to 2050. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:422-429.

2. Sherman RA. Postamputation pain. In: Jensen TS, Wilson PR, Rice AS, eds. Clinical Pain Management: Chronic Pain. London: Hodder Arnold Publishing; 2002;32:427-436.

3. Wartan SW, Hamann W, Wedley JR, et al. Phantom pain and sensation among British veteran amputees. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78:652-659.

4. Halbert J, Crotty M, Cameron ID. Evidence for the optimal management of acute and chronic phantom pain: a systematic review. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:84-92.

5. Baron R, Wasner G, Lindner V. Optimal treatment of phantom limb pain in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 1998;12:361-376.

6. Finnerup NB, Otto M, McQuay HJ, et al. Algorithm for neuropathic pain treatment: an evidence-based proposal. Pain. 2005;118:289-305.

7. Huse E, Larbig W, Flor H, et al. The effect of opioids on phantom limb pain and cortical reorganization. Pain. 2001;90:47-55.

8. Robinson LR, Czerniecki JM, Ehde DM, et al. Trial of amitriptyline for relief of pain in amputees: results of a randomized controlled study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1-6.

9. Bone M, Critchley P, Buggy DJ. Gabapentin in postamputation phantom limb pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2002;27:481-486.

10. Nikolajsen L, Finnerup NB, Kramp S, et al. A randomized study of the effects of gabapentin on post-amputation pain. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:1008-1015.

11. Chan BL, Witt R, Charrow AP, et al. Mirror therapy for phantom limb pain. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2206-2207.

12. Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for rehabilitation of lower amputation. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense; 2007:1-55. Available at: www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?doc_id=11758&nbr=006060&string=amputation. Accessed December 13, 2008.

1. Ziegler-Graham K, MacKenzie EI, Ephraim PL, et al. Estimating the prevalence of limb loss in the United States: 2005 to 2050. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:422-429.

2. Sherman RA. Postamputation pain. In: Jensen TS, Wilson PR, Rice AS, eds. Clinical Pain Management: Chronic Pain. London: Hodder Arnold Publishing; 2002;32:427-436.

3. Wartan SW, Hamann W, Wedley JR, et al. Phantom pain and sensation among British veteran amputees. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78:652-659.

4. Halbert J, Crotty M, Cameron ID. Evidence for the optimal management of acute and chronic phantom pain: a systematic review. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:84-92.

5. Baron R, Wasner G, Lindner V. Optimal treatment of phantom limb pain in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 1998;12:361-376.

6. Finnerup NB, Otto M, McQuay HJ, et al. Algorithm for neuropathic pain treatment: an evidence-based proposal. Pain. 2005;118:289-305.

7. Huse E, Larbig W, Flor H, et al. The effect of opioids on phantom limb pain and cortical reorganization. Pain. 2001;90:47-55.

8. Robinson LR, Czerniecki JM, Ehde DM, et al. Trial of amitriptyline for relief of pain in amputees: results of a randomized controlled study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1-6.

9. Bone M, Critchley P, Buggy DJ. Gabapentin in postamputation phantom limb pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2002;27:481-486.

10. Nikolajsen L, Finnerup NB, Kramp S, et al. A randomized study of the effects of gabapentin on post-amputation pain. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:1008-1015.

11. Chan BL, Witt R, Charrow AP, et al. Mirror therapy for phantom limb pain. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2206-2207.

12. Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for rehabilitation of lower amputation. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense; 2007:1-55. Available at: www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?doc_id=11758&nbr=006060&string=amputation. Accessed December 13, 2008.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network