User login

Buprenorphine to treat opioid use disorder: A practical guide

Opioids were involved in 42,249 deaths in the United States in 2016, and opioid overdoses have quintupled since 1999.1 Among the causes behind these statistics is increased opiate prescribing by physicians—with primary care providers accounting for about one half of opiate prescriptions.2 As a result, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has issued a 4-part response for physicians,3 which includes careful opiate prescribing, expanded access to naloxone, prevention of opioid use disorder (OUD), and expanded use of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) of addiction—with the goal of preventing and managing OUD.

CASE

Fred R, a 55-year-old man who has been taking oxycodone, 70 mg/d, for chronic pain for longer than 10 years, visits your clinic for a prescription refill. His prescription monitoring program confirms the long history of regular oxycodone use, with the dosage escalating over the past 6 months. He recently was discharged from the hospital after an overdose of opiates.

Mr. R admits to using heroin after running out of oxycodone. He is in mild withdrawal, with a score of 8 (of a possible 48) on the Clinical Opioid Withdrawal Scale4 (COWS, which assigns point values to 11 common symptoms to gauge the severity of opioid withdrawal and, by inference, the patient’s degree of physical dependence). You determine that Mr. R is frightened about his use of oxycodone and would like to stop; he has tried to stop several times on his own but always relapses when withdrawal becomes severe.

How would you proceed with the care of this patient?

What is OUD? How is the diagnosis made?

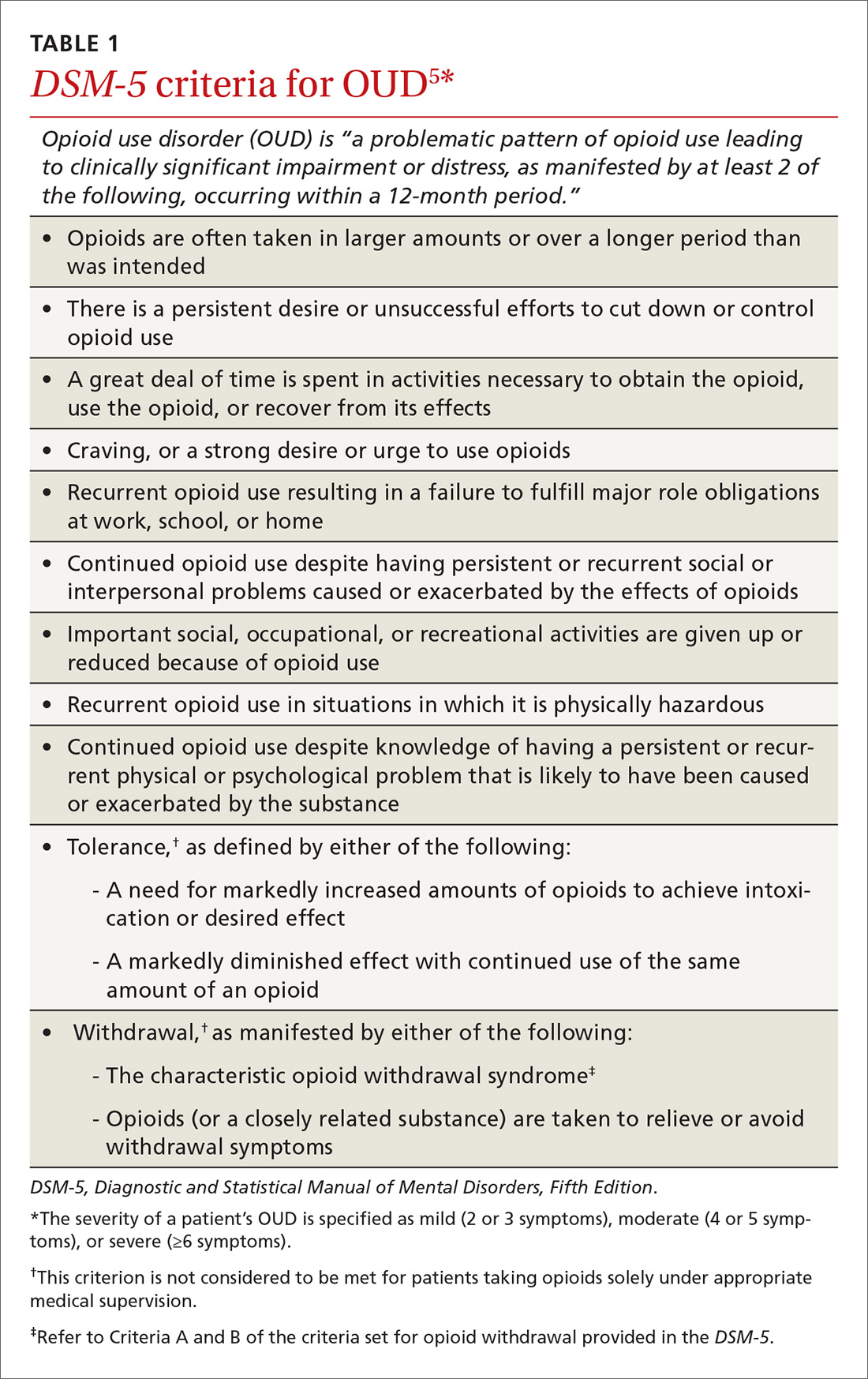

OUD is a combination of cognitive, behavioral, and physiologic symptoms arising from continued use of opioids despite significant health, legal, or relationship problems related to their use. The disorder is diagnosed based on specific criteria provided in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5)(TABLE 1)5 and is revealed by 1) a careful history that delineates a problematic pattern of opioid use, 2) physical examination, and 3) urine toxicology screen.

Identification of acute opioid intoxication can also be useful when working up a patient in whom OUD is suspected; findings of acute opioid intoxication on physical examination include constricted pupils, head-nodding, excessive sleepiness, and drooping eyelids. Other physical signs of illicit opioid use include track marks around veins of the arm, evidence of repeated trauma, and stigmata of liver dysfunction. Withdrawal can present as agitation, rhinorrhea, dilated pupils, nausea, diarrhea, yawning, and gooseflesh. The COWS, which, as noted in the case, assigns point values to withdrawal symptoms, can be helpful in determining the severity of withdrawal.4

What is the differential Dx of OUD?

When OUD is likely, but not clearly diagnosable, on the basis of findings, consider a mental health disorder: depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder, personality disorder, and polysubstance use disorder. Concurrent diagnosis of substance abuse and a mental health disorder is common; treatment requires that both disorders be addressed simultaneously.6 Assessing for use or abuse of, and addiction to, other substances is vital to ensure proper diagnosis and effective therapy. Polysubstance dependence can be more difficult to treat than single-substance abuse or addiction alone.

Continue to: How is OUD treated?

How is OUD treated?

This article reviews MAT with buprenorphine; other MAT options include methadone and naltrexone. Regardless of the indicated agent chosen, MAT has been shown to be superior to abstinence alone or abstinence with counseling interventions in maintaining sobriety.7

Evidence of efficacy. In a longitudinal cohort study of patients who received MAT with buprenorphine initiated in general practice, patients in whom buprenorphine therapy was interrupted had a greatly increased risk of all-cause mortality (hazard ratio=29.04; 95% confidence interval, 10.04-83.99).8 The study highlights the harm-reduction treatment philosophy of MAT with buprenorphine: The regimen can be used to keep a patient alive while working toward sobriety.

We encourage physicians to treat addiction as they would any chronic disease. The strategy includes anticipating relapse, engaging support systems (eg, family, counselors, social groups, Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous [NA]), and working with the patient to obtain a higher level of care, as indicated.

Pharmacology and induction. Alone or in combination with naloxone, buprenorphine can be used as in-office-based MAT. Buprenorphine is a partial opiate agonist that binds tightly to opioid receptors and can block the effects of other opiates. An advantage of buprenorphine is its low likelihood of overdose, due to the drug’s so-called ceiling effect at a dosage of 24 mg/d;9 dosages above this amount have little increased medication effect.

Dosing of buprenorphine is variable from patient to patient, with a maximum dosage of 24 mg/d. Therapy can be initiated safely at home, although some physicians prefer in-office induction. It is important that the patient be in moderate withdrawal (as determined by the score on the COWS) before initiation, because buprenorphine, as a partial agonist, can precipitate withdrawal by displacing full opiate agonists from opioid receptors.

Continue to: In our experience...

In our experience, a common induction method is to give 2 to 4 mg buprenorphine, followed by a 1-hour assessment of withdrawal symptoms. This can be repeated for multiple doses until withdrawal is relieved, usually with a maximum dosage of 6 to 8 mg in the initial 1 or 2 days of treatment. Rapid reassessment is required after induction, preferably in 1 to 3 days. Dosing should be gradually increased in 2- to 4-mg increments until 1) the patient has no withdrawal symptoms in a 24-hour period and 2) craving for opiates is adequately controlled.

Note: Primary care physicians must complete an 8-hour online training course to obtain a US Drug Enforcement Administration waiver to prescribe buprenorphine.

How should coordination of care be approached?

Actual prescribing and monitoring of buprenorphine is not complex, but many physicians are intimidated by the perceived difficulty of coordination of care. The American Society of Addiction Medicine's national practice guideline recommends that buprenorphine and other MAT protocols be offered as a part of a comprehensive treatment plan that includes psychosocial treatment.7 This combination leads to the greatest potential for ongoing remission of OUD. Although many primary care clinics do not have chemical dependency counseling available at their primary location, partnering with community organizations and other mental health resources can meet this need. Coordination of care with home services, behavioral health, and psychiatry is common in primary care, and is no different for OUD.

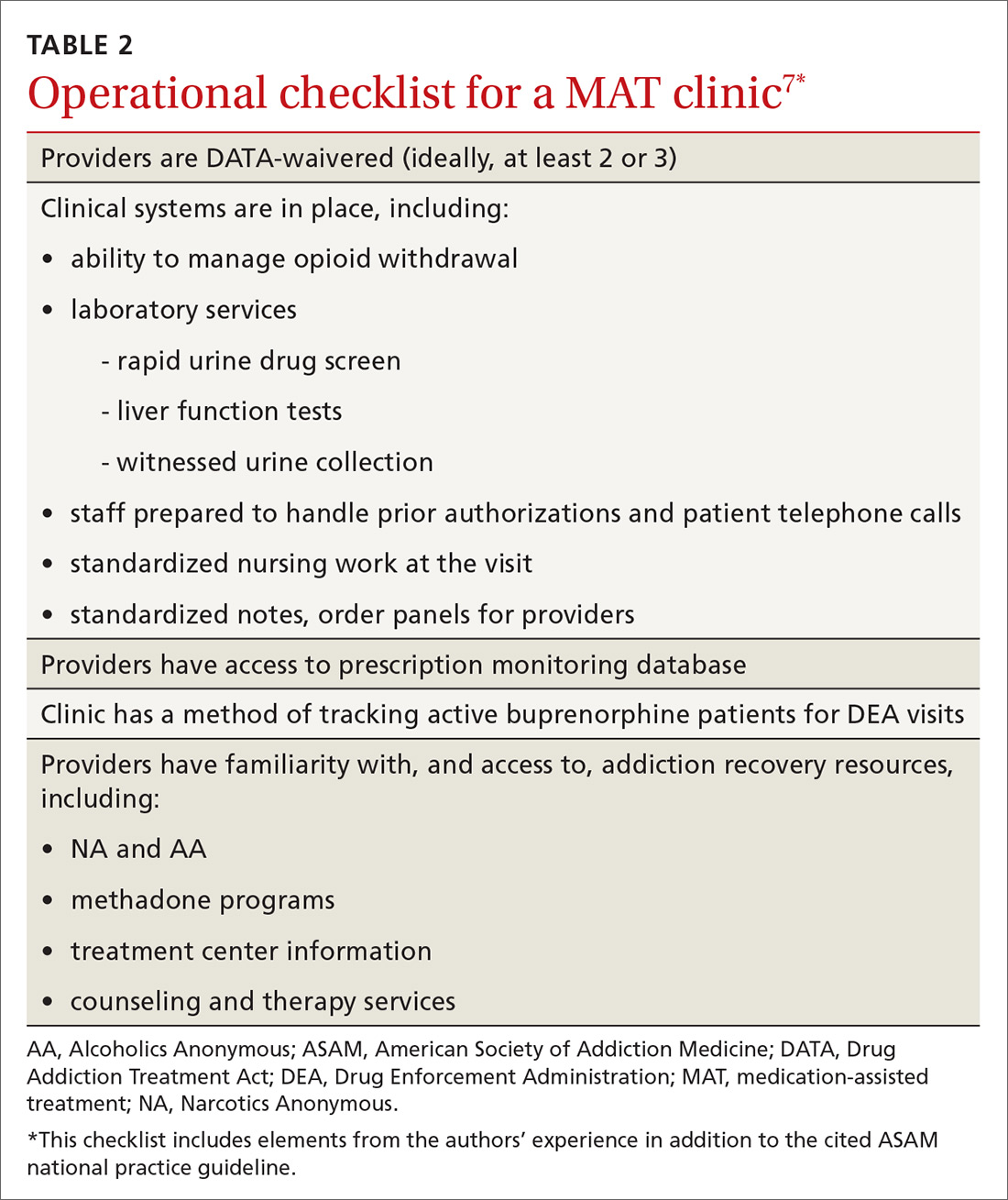

There are administrative requirements for a clinic that offers MAT (TABLE 2),7 including tracking of numbers of patients who are taking buprenorphine. During the first year of prescribing buprenorphine, a physician or other provider is permitted to care for only 30 patients; once the first year has passed, that provider can apply to care for as many as 100 patients. In addition, the Drug Enforcement Administration might conduct site visits to ensure that proper documentation and tracking of patients is being undertaken. These requirements can seem daunting, but careful monitoring of patient panels can alleviate concerns. For clinics that use an electronic medical record, we recommend developing the capability to pull lists by either buprenorphine prescriptions or diagnosis codes.

Continue to: CASE

CASE

After you and Mr. R discuss his addiction, you decide to initiate treatment that includes buprenorphine. You have a specimen collected for a urine toxicology screen and blood drawn for a baseline liver function panel, hepatitis panel, and human immunodeficiency virus screen, and provide him with resources (nearby treatment center, an NA meeting location) for treating OUD. You write a prescription for #8 buprenorphine and naloxone, 2 mg/0.5 mg films, and instruct Mr. R to: take 1 film when withdrawal symptoms become worse; wait 1 hour; and take another film if he is still experiencing withdrawal symptoms. He can repeat this dosing regimen until he reaches 8 mg/d of buprenorphine (4 films). You schedule follow-up in 2 days.

At follow-up, the patient reports that taking 3 films alleviated withdrawal symptoms, but that symptoms returned approximately 12 hours later, at which time he took the fourth film. This helped him through until the next day, when he again took 3 films in the morning and 1 film in the late evening. He feels that this regimen is helping relieve withdrawal symptoms and cravings. You provide a prescription for buprenorphine and naloxone, 8 mg/2 mg daily, and request a follow-up visit in 5 days.

At the next visit, Mr. R reports that he still has cravings for oxycodone. You increase the dosage of buprenorphine and naloxone to 12 mg/3 mg daily.

At the next visit, he reports no longer having cravings.

You continue to monitor Mr. R with urine drug screening and discussion of his recovery with the help of his family and support network. After 3 months of consistent visits, he fails to show up for his every-2-or-3-week appointment.

Continue to: Four days later...

Four days later, Mr. R shows up at the clinic, apologizing for missing the appointment and assuring you that this won’t happen again. Rapid urine drug screening is positive for morphine. When confronted, he admits using heroin. He reports that his cravings had increased, for which he took buprenorphine and naloxone above the prescribed dosage, and ran out of films early. He then used heroin 3 times to prevent withdrawal.

Mr. R admits that he has been having cravings for oxycodone since the start of treatment for addiction, but thought he was strong enough to overcome the cravings. He feels disappointed and embarrassed about this; he wants to continue with buprenorphine, he tells you, but worries that you will refuse to continue seeing him now.

Using shared decision-making, you opt to increase the buprenorphine dosage by 4 mg (to 16 mg/d—ie, 2 films of buprenorphine and naloxone, 8 mg/2 mg) to alleviate cravings. You instruct him to engage his support network, including his family and NA sponsor, and to start outpatient group therapy. He tells you that he is willing to go back to weekly clinic visits until he is stabilized.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tanner Nissly, DO, University of Minnesota Medical School Twin Cities, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, 1020 West Broadway Avenue, Minneapolis, MN 55411; nissl003@umn.edu.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid overdose. December 19, 2017. Available at: www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html. Accessed June 22, 2018.

2. Daubresse M, Chang H, Yu Y, et al. Ambulatory diagnosis and treatment of nonmalignant pain in the United States, 2000-2010. Med Care. 2013;51:870-878.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overdose prevention. August 31, 2017. Available at: www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prevention/index.html. Accessed June 29, 2018.

4. Wesson DR, Ling W. The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS). J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35:253-259. Available at: www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/files/ClinicalOpiateWithdrawalScale.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2018.

5. Opioid use disorder: Diagnostic criteria. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. Available at: http://pcssnow.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/5B-DSM-5-Opioid-Use-Disorder-Diagnostic-Criteria.pdf. Accessed June 23, 2018.

6. Brunette MF, Mueser KT. Psychosocial interventions for the long-term management of patients with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 7):10-17.

7. Kampman K, Abraham A, Dugosh K, et al; ASAM Quality Improvement Council. The ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Use of Medications in the Treatment of Addiction Involving Opioid Use. Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 2015. Available at: www.asam.org/docs/default-source/practice-support/guidelines-and-consensus-docs/asam-national-practice-guideline-supplement.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2018.

8. Depouy J, Palmaro A, Fatséas M, et al. Mortality associated with time in and out of buprenorphine treatment in French office-based general practice: A 7-year cohort study. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15:355-358.

9. Walsh SL, Preston KL, Stitzer ML, et al. Clinical pharmacology of buprenorphine: ceiling effects at high doses. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;55:569-580.

Opioids were involved in 42,249 deaths in the United States in 2016, and opioid overdoses have quintupled since 1999.1 Among the causes behind these statistics is increased opiate prescribing by physicians—with primary care providers accounting for about one half of opiate prescriptions.2 As a result, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has issued a 4-part response for physicians,3 which includes careful opiate prescribing, expanded access to naloxone, prevention of opioid use disorder (OUD), and expanded use of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) of addiction—with the goal of preventing and managing OUD.

CASE

Fred R, a 55-year-old man who has been taking oxycodone, 70 mg/d, for chronic pain for longer than 10 years, visits your clinic for a prescription refill. His prescription monitoring program confirms the long history of regular oxycodone use, with the dosage escalating over the past 6 months. He recently was discharged from the hospital after an overdose of opiates.

Mr. R admits to using heroin after running out of oxycodone. He is in mild withdrawal, with a score of 8 (of a possible 48) on the Clinical Opioid Withdrawal Scale4 (COWS, which assigns point values to 11 common symptoms to gauge the severity of opioid withdrawal and, by inference, the patient’s degree of physical dependence). You determine that Mr. R is frightened about his use of oxycodone and would like to stop; he has tried to stop several times on his own but always relapses when withdrawal becomes severe.

How would you proceed with the care of this patient?

What is OUD? How is the diagnosis made?

OUD is a combination of cognitive, behavioral, and physiologic symptoms arising from continued use of opioids despite significant health, legal, or relationship problems related to their use. The disorder is diagnosed based on specific criteria provided in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5)(TABLE 1)5 and is revealed by 1) a careful history that delineates a problematic pattern of opioid use, 2) physical examination, and 3) urine toxicology screen.

Identification of acute opioid intoxication can also be useful when working up a patient in whom OUD is suspected; findings of acute opioid intoxication on physical examination include constricted pupils, head-nodding, excessive sleepiness, and drooping eyelids. Other physical signs of illicit opioid use include track marks around veins of the arm, evidence of repeated trauma, and stigmata of liver dysfunction. Withdrawal can present as agitation, rhinorrhea, dilated pupils, nausea, diarrhea, yawning, and gooseflesh. The COWS, which, as noted in the case, assigns point values to withdrawal symptoms, can be helpful in determining the severity of withdrawal.4

What is the differential Dx of OUD?

When OUD is likely, but not clearly diagnosable, on the basis of findings, consider a mental health disorder: depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder, personality disorder, and polysubstance use disorder. Concurrent diagnosis of substance abuse and a mental health disorder is common; treatment requires that both disorders be addressed simultaneously.6 Assessing for use or abuse of, and addiction to, other substances is vital to ensure proper diagnosis and effective therapy. Polysubstance dependence can be more difficult to treat than single-substance abuse or addiction alone.

Continue to: How is OUD treated?

How is OUD treated?

This article reviews MAT with buprenorphine; other MAT options include methadone and naltrexone. Regardless of the indicated agent chosen, MAT has been shown to be superior to abstinence alone or abstinence with counseling interventions in maintaining sobriety.7

Evidence of efficacy. In a longitudinal cohort study of patients who received MAT with buprenorphine initiated in general practice, patients in whom buprenorphine therapy was interrupted had a greatly increased risk of all-cause mortality (hazard ratio=29.04; 95% confidence interval, 10.04-83.99).8 The study highlights the harm-reduction treatment philosophy of MAT with buprenorphine: The regimen can be used to keep a patient alive while working toward sobriety.

We encourage physicians to treat addiction as they would any chronic disease. The strategy includes anticipating relapse, engaging support systems (eg, family, counselors, social groups, Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous [NA]), and working with the patient to obtain a higher level of care, as indicated.

Pharmacology and induction. Alone or in combination with naloxone, buprenorphine can be used as in-office-based MAT. Buprenorphine is a partial opiate agonist that binds tightly to opioid receptors and can block the effects of other opiates. An advantage of buprenorphine is its low likelihood of overdose, due to the drug’s so-called ceiling effect at a dosage of 24 mg/d;9 dosages above this amount have little increased medication effect.

Dosing of buprenorphine is variable from patient to patient, with a maximum dosage of 24 mg/d. Therapy can be initiated safely at home, although some physicians prefer in-office induction. It is important that the patient be in moderate withdrawal (as determined by the score on the COWS) before initiation, because buprenorphine, as a partial agonist, can precipitate withdrawal by displacing full opiate agonists from opioid receptors.

Continue to: In our experience...

In our experience, a common induction method is to give 2 to 4 mg buprenorphine, followed by a 1-hour assessment of withdrawal symptoms. This can be repeated for multiple doses until withdrawal is relieved, usually with a maximum dosage of 6 to 8 mg in the initial 1 or 2 days of treatment. Rapid reassessment is required after induction, preferably in 1 to 3 days. Dosing should be gradually increased in 2- to 4-mg increments until 1) the patient has no withdrawal symptoms in a 24-hour period and 2) craving for opiates is adequately controlled.

Note: Primary care physicians must complete an 8-hour online training course to obtain a US Drug Enforcement Administration waiver to prescribe buprenorphine.

How should coordination of care be approached?

Actual prescribing and monitoring of buprenorphine is not complex, but many physicians are intimidated by the perceived difficulty of coordination of care. The American Society of Addiction Medicine's national practice guideline recommends that buprenorphine and other MAT protocols be offered as a part of a comprehensive treatment plan that includes psychosocial treatment.7 This combination leads to the greatest potential for ongoing remission of OUD. Although many primary care clinics do not have chemical dependency counseling available at their primary location, partnering with community organizations and other mental health resources can meet this need. Coordination of care with home services, behavioral health, and psychiatry is common in primary care, and is no different for OUD.

There are administrative requirements for a clinic that offers MAT (TABLE 2),7 including tracking of numbers of patients who are taking buprenorphine. During the first year of prescribing buprenorphine, a physician or other provider is permitted to care for only 30 patients; once the first year has passed, that provider can apply to care for as many as 100 patients. In addition, the Drug Enforcement Administration might conduct site visits to ensure that proper documentation and tracking of patients is being undertaken. These requirements can seem daunting, but careful monitoring of patient panels can alleviate concerns. For clinics that use an electronic medical record, we recommend developing the capability to pull lists by either buprenorphine prescriptions or diagnosis codes.

Continue to: CASE

CASE

After you and Mr. R discuss his addiction, you decide to initiate treatment that includes buprenorphine. You have a specimen collected for a urine toxicology screen and blood drawn for a baseline liver function panel, hepatitis panel, and human immunodeficiency virus screen, and provide him with resources (nearby treatment center, an NA meeting location) for treating OUD. You write a prescription for #8 buprenorphine and naloxone, 2 mg/0.5 mg films, and instruct Mr. R to: take 1 film when withdrawal symptoms become worse; wait 1 hour; and take another film if he is still experiencing withdrawal symptoms. He can repeat this dosing regimen until he reaches 8 mg/d of buprenorphine (4 films). You schedule follow-up in 2 days.

At follow-up, the patient reports that taking 3 films alleviated withdrawal symptoms, but that symptoms returned approximately 12 hours later, at which time he took the fourth film. This helped him through until the next day, when he again took 3 films in the morning and 1 film in the late evening. He feels that this regimen is helping relieve withdrawal symptoms and cravings. You provide a prescription for buprenorphine and naloxone, 8 mg/2 mg daily, and request a follow-up visit in 5 days.

At the next visit, Mr. R reports that he still has cravings for oxycodone. You increase the dosage of buprenorphine and naloxone to 12 mg/3 mg daily.

At the next visit, he reports no longer having cravings.

You continue to monitor Mr. R with urine drug screening and discussion of his recovery with the help of his family and support network. After 3 months of consistent visits, he fails to show up for his every-2-or-3-week appointment.

Continue to: Four days later...

Four days later, Mr. R shows up at the clinic, apologizing for missing the appointment and assuring you that this won’t happen again. Rapid urine drug screening is positive for morphine. When confronted, he admits using heroin. He reports that his cravings had increased, for which he took buprenorphine and naloxone above the prescribed dosage, and ran out of films early. He then used heroin 3 times to prevent withdrawal.

Mr. R admits that he has been having cravings for oxycodone since the start of treatment for addiction, but thought he was strong enough to overcome the cravings. He feels disappointed and embarrassed about this; he wants to continue with buprenorphine, he tells you, but worries that you will refuse to continue seeing him now.

Using shared decision-making, you opt to increase the buprenorphine dosage by 4 mg (to 16 mg/d—ie, 2 films of buprenorphine and naloxone, 8 mg/2 mg) to alleviate cravings. You instruct him to engage his support network, including his family and NA sponsor, and to start outpatient group therapy. He tells you that he is willing to go back to weekly clinic visits until he is stabilized.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tanner Nissly, DO, University of Minnesota Medical School Twin Cities, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, 1020 West Broadway Avenue, Minneapolis, MN 55411; nissl003@umn.edu.

Opioids were involved in 42,249 deaths in the United States in 2016, and opioid overdoses have quintupled since 1999.1 Among the causes behind these statistics is increased opiate prescribing by physicians—with primary care providers accounting for about one half of opiate prescriptions.2 As a result, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has issued a 4-part response for physicians,3 which includes careful opiate prescribing, expanded access to naloxone, prevention of opioid use disorder (OUD), and expanded use of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) of addiction—with the goal of preventing and managing OUD.

CASE

Fred R, a 55-year-old man who has been taking oxycodone, 70 mg/d, for chronic pain for longer than 10 years, visits your clinic for a prescription refill. His prescription monitoring program confirms the long history of regular oxycodone use, with the dosage escalating over the past 6 months. He recently was discharged from the hospital after an overdose of opiates.

Mr. R admits to using heroin after running out of oxycodone. He is in mild withdrawal, with a score of 8 (of a possible 48) on the Clinical Opioid Withdrawal Scale4 (COWS, which assigns point values to 11 common symptoms to gauge the severity of opioid withdrawal and, by inference, the patient’s degree of physical dependence). You determine that Mr. R is frightened about his use of oxycodone and would like to stop; he has tried to stop several times on his own but always relapses when withdrawal becomes severe.

How would you proceed with the care of this patient?

What is OUD? How is the diagnosis made?

OUD is a combination of cognitive, behavioral, and physiologic symptoms arising from continued use of opioids despite significant health, legal, or relationship problems related to their use. The disorder is diagnosed based on specific criteria provided in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5)(TABLE 1)5 and is revealed by 1) a careful history that delineates a problematic pattern of opioid use, 2) physical examination, and 3) urine toxicology screen.

Identification of acute opioid intoxication can also be useful when working up a patient in whom OUD is suspected; findings of acute opioid intoxication on physical examination include constricted pupils, head-nodding, excessive sleepiness, and drooping eyelids. Other physical signs of illicit opioid use include track marks around veins of the arm, evidence of repeated trauma, and stigmata of liver dysfunction. Withdrawal can present as agitation, rhinorrhea, dilated pupils, nausea, diarrhea, yawning, and gooseflesh. The COWS, which, as noted in the case, assigns point values to withdrawal symptoms, can be helpful in determining the severity of withdrawal.4

What is the differential Dx of OUD?

When OUD is likely, but not clearly diagnosable, on the basis of findings, consider a mental health disorder: depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder, personality disorder, and polysubstance use disorder. Concurrent diagnosis of substance abuse and a mental health disorder is common; treatment requires that both disorders be addressed simultaneously.6 Assessing for use or abuse of, and addiction to, other substances is vital to ensure proper diagnosis and effective therapy. Polysubstance dependence can be more difficult to treat than single-substance abuse or addiction alone.

Continue to: How is OUD treated?

How is OUD treated?

This article reviews MAT with buprenorphine; other MAT options include methadone and naltrexone. Regardless of the indicated agent chosen, MAT has been shown to be superior to abstinence alone or abstinence with counseling interventions in maintaining sobriety.7

Evidence of efficacy. In a longitudinal cohort study of patients who received MAT with buprenorphine initiated in general practice, patients in whom buprenorphine therapy was interrupted had a greatly increased risk of all-cause mortality (hazard ratio=29.04; 95% confidence interval, 10.04-83.99).8 The study highlights the harm-reduction treatment philosophy of MAT with buprenorphine: The regimen can be used to keep a patient alive while working toward sobriety.

We encourage physicians to treat addiction as they would any chronic disease. The strategy includes anticipating relapse, engaging support systems (eg, family, counselors, social groups, Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous [NA]), and working with the patient to obtain a higher level of care, as indicated.

Pharmacology and induction. Alone or in combination with naloxone, buprenorphine can be used as in-office-based MAT. Buprenorphine is a partial opiate agonist that binds tightly to opioid receptors and can block the effects of other opiates. An advantage of buprenorphine is its low likelihood of overdose, due to the drug’s so-called ceiling effect at a dosage of 24 mg/d;9 dosages above this amount have little increased medication effect.

Dosing of buprenorphine is variable from patient to patient, with a maximum dosage of 24 mg/d. Therapy can be initiated safely at home, although some physicians prefer in-office induction. It is important that the patient be in moderate withdrawal (as determined by the score on the COWS) before initiation, because buprenorphine, as a partial agonist, can precipitate withdrawal by displacing full opiate agonists from opioid receptors.

Continue to: In our experience...

In our experience, a common induction method is to give 2 to 4 mg buprenorphine, followed by a 1-hour assessment of withdrawal symptoms. This can be repeated for multiple doses until withdrawal is relieved, usually with a maximum dosage of 6 to 8 mg in the initial 1 or 2 days of treatment. Rapid reassessment is required after induction, preferably in 1 to 3 days. Dosing should be gradually increased in 2- to 4-mg increments until 1) the patient has no withdrawal symptoms in a 24-hour period and 2) craving for opiates is adequately controlled.

Note: Primary care physicians must complete an 8-hour online training course to obtain a US Drug Enforcement Administration waiver to prescribe buprenorphine.

How should coordination of care be approached?

Actual prescribing and monitoring of buprenorphine is not complex, but many physicians are intimidated by the perceived difficulty of coordination of care. The American Society of Addiction Medicine's national practice guideline recommends that buprenorphine and other MAT protocols be offered as a part of a comprehensive treatment plan that includes psychosocial treatment.7 This combination leads to the greatest potential for ongoing remission of OUD. Although many primary care clinics do not have chemical dependency counseling available at their primary location, partnering with community organizations and other mental health resources can meet this need. Coordination of care with home services, behavioral health, and psychiatry is common in primary care, and is no different for OUD.

There are administrative requirements for a clinic that offers MAT (TABLE 2),7 including tracking of numbers of patients who are taking buprenorphine. During the first year of prescribing buprenorphine, a physician or other provider is permitted to care for only 30 patients; once the first year has passed, that provider can apply to care for as many as 100 patients. In addition, the Drug Enforcement Administration might conduct site visits to ensure that proper documentation and tracking of patients is being undertaken. These requirements can seem daunting, but careful monitoring of patient panels can alleviate concerns. For clinics that use an electronic medical record, we recommend developing the capability to pull lists by either buprenorphine prescriptions or diagnosis codes.

Continue to: CASE

CASE

After you and Mr. R discuss his addiction, you decide to initiate treatment that includes buprenorphine. You have a specimen collected for a urine toxicology screen and blood drawn for a baseline liver function panel, hepatitis panel, and human immunodeficiency virus screen, and provide him with resources (nearby treatment center, an NA meeting location) for treating OUD. You write a prescription for #8 buprenorphine and naloxone, 2 mg/0.5 mg films, and instruct Mr. R to: take 1 film when withdrawal symptoms become worse; wait 1 hour; and take another film if he is still experiencing withdrawal symptoms. He can repeat this dosing regimen until he reaches 8 mg/d of buprenorphine (4 films). You schedule follow-up in 2 days.

At follow-up, the patient reports that taking 3 films alleviated withdrawal symptoms, but that symptoms returned approximately 12 hours later, at which time he took the fourth film. This helped him through until the next day, when he again took 3 films in the morning and 1 film in the late evening. He feels that this regimen is helping relieve withdrawal symptoms and cravings. You provide a prescription for buprenorphine and naloxone, 8 mg/2 mg daily, and request a follow-up visit in 5 days.

At the next visit, Mr. R reports that he still has cravings for oxycodone. You increase the dosage of buprenorphine and naloxone to 12 mg/3 mg daily.

At the next visit, he reports no longer having cravings.

You continue to monitor Mr. R with urine drug screening and discussion of his recovery with the help of his family and support network. After 3 months of consistent visits, he fails to show up for his every-2-or-3-week appointment.

Continue to: Four days later...

Four days later, Mr. R shows up at the clinic, apologizing for missing the appointment and assuring you that this won’t happen again. Rapid urine drug screening is positive for morphine. When confronted, he admits using heroin. He reports that his cravings had increased, for which he took buprenorphine and naloxone above the prescribed dosage, and ran out of films early. He then used heroin 3 times to prevent withdrawal.

Mr. R admits that he has been having cravings for oxycodone since the start of treatment for addiction, but thought he was strong enough to overcome the cravings. He feels disappointed and embarrassed about this; he wants to continue with buprenorphine, he tells you, but worries that you will refuse to continue seeing him now.

Using shared decision-making, you opt to increase the buprenorphine dosage by 4 mg (to 16 mg/d—ie, 2 films of buprenorphine and naloxone, 8 mg/2 mg) to alleviate cravings. You instruct him to engage his support network, including his family and NA sponsor, and to start outpatient group therapy. He tells you that he is willing to go back to weekly clinic visits until he is stabilized.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tanner Nissly, DO, University of Minnesota Medical School Twin Cities, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, 1020 West Broadway Avenue, Minneapolis, MN 55411; nissl003@umn.edu.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid overdose. December 19, 2017. Available at: www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html. Accessed June 22, 2018.

2. Daubresse M, Chang H, Yu Y, et al. Ambulatory diagnosis and treatment of nonmalignant pain in the United States, 2000-2010. Med Care. 2013;51:870-878.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overdose prevention. August 31, 2017. Available at: www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prevention/index.html. Accessed June 29, 2018.

4. Wesson DR, Ling W. The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS). J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35:253-259. Available at: www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/files/ClinicalOpiateWithdrawalScale.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2018.

5. Opioid use disorder: Diagnostic criteria. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. Available at: http://pcssnow.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/5B-DSM-5-Opioid-Use-Disorder-Diagnostic-Criteria.pdf. Accessed June 23, 2018.

6. Brunette MF, Mueser KT. Psychosocial interventions for the long-term management of patients with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 7):10-17.

7. Kampman K, Abraham A, Dugosh K, et al; ASAM Quality Improvement Council. The ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Use of Medications in the Treatment of Addiction Involving Opioid Use. Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 2015. Available at: www.asam.org/docs/default-source/practice-support/guidelines-and-consensus-docs/asam-national-practice-guideline-supplement.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2018.

8. Depouy J, Palmaro A, Fatséas M, et al. Mortality associated with time in and out of buprenorphine treatment in French office-based general practice: A 7-year cohort study. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15:355-358.

9. Walsh SL, Preston KL, Stitzer ML, et al. Clinical pharmacology of buprenorphine: ceiling effects at high doses. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;55:569-580.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid overdose. December 19, 2017. Available at: www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html. Accessed June 22, 2018.

2. Daubresse M, Chang H, Yu Y, et al. Ambulatory diagnosis and treatment of nonmalignant pain in the United States, 2000-2010. Med Care. 2013;51:870-878.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overdose prevention. August 31, 2017. Available at: www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prevention/index.html. Accessed June 29, 2018.

4. Wesson DR, Ling W. The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS). J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35:253-259. Available at: www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/files/ClinicalOpiateWithdrawalScale.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2018.

5. Opioid use disorder: Diagnostic criteria. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. Available at: http://pcssnow.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/5B-DSM-5-Opioid-Use-Disorder-Diagnostic-Criteria.pdf. Accessed June 23, 2018.

6. Brunette MF, Mueser KT. Psychosocial interventions for the long-term management of patients with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 7):10-17.

7. Kampman K, Abraham A, Dugosh K, et al; ASAM Quality Improvement Council. The ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Use of Medications in the Treatment of Addiction Involving Opioid Use. Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addiction Medicine; 2015. Available at: www.asam.org/docs/default-source/practice-support/guidelines-and-consensus-docs/asam-national-practice-guideline-supplement.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2018.

8. Depouy J, Palmaro A, Fatséas M, et al. Mortality associated with time in and out of buprenorphine treatment in French office-based general practice: A 7-year cohort study. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15:355-358.

9. Walsh SL, Preston KL, Stitzer ML, et al. Clinical pharmacology of buprenorphine: ceiling effects at high doses. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;55:569-580.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Use signs of intoxication, signs of withdrawal, urine drug screening, and diagnostic criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, to screen for, and diagnose, opioid use disorder. C

› Offer and institute medication-assisted treatment when appropriate to reduce the risk of opioid-related and overall mortality in patients with opioid use disorder. A

› Identify and treat comorbid psychiatric disorders in patients with opioid use disorder, which provides benefit during treatment of the disorder. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

An Antiemetic for Irritable Bowel Syndrome?

PRACTICE CHANGER

Consider prescribing ondansetron (up to 24 mg/d) for patients who have irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea (IBS-D).1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a well-done double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized controlled trial (RCT).1

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 23-year-old woman who was diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) comes to your clinic with complaints of increased frequency of defecation with watery stools and generalized, cramping abdominal pain. She also notes increased passage of mucus and a sensation of incomplete evacuation.

She says the only thing that relieves her pain is defecation. She has tried loperamide, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen without relief. She does not have Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis. What else can you offer her that is safe and effective?

IBS is a chronic, episodic functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort and altered bowel habits: constipation (IBS-C), diarrhea (IBS-D), or alternating periods of both—mixed (IBS-M).2 The diagnosis is based on Rome III criteria, which include recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort on at least three days per month in the past three months associated with two or more of the following: improvement with defecation, onset associated with a change in frequency of stool, and onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool.3 IBS often is unrecognized or untreated, and as few as 25% of patients with IBS seek care.4

IBS-D affects approximately 5% of the general population in North America.5,6 IBS-D is associated with a considerably decreased quality of life and is a common cause of work absenteeism.7,8 Because many conditions can cause diarrhea, patients typically undergo numerous tests before receiving an accurate diagnosis, which creates a financial burden.9

For many patients, current IBS treatments—including fiber supplements, laxatives, antidiarrheal medications, antispasmodics, and antidepressants such as tricyclics and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors—are unsatisfactory.10 Alosetron, a 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 (5-HT3) receptor antagonist, has been used to treat IBS-D,11 but this medication was voluntarily withdrawn from the US market in 2000 due to concerns about ischemic colitis and severe constipation.12 It was reintroduced in 2002 but can be prescribed only by clinicians who enroll in a prescribing program provided by the manufacturer, and there are restrictions on its use.

Ondansetron—another 5-HT3 receptor antagonist used to treat nausea and vomiting caused by chemotherapy—may be another option for treating IBS-D. Garsed et al1 recently conducted an RCT to evaluate the efficacy of ondansetron for patients with IBS-D.

Study summary >>

STUDY SUMMARY

Ondansetron improves stool consistency, severity of IBS symptoms

In a five-week, double-blind crossover RCT, Garsed et al1 compared ondansetron with placebo for symptom relief in 120 patients who met Rome III criteria for IBS-D. All patients were ages 18 to 75 and had no evidence of inflammatory bowel disease. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy or breastfeeding, unwillingness to stop antidiarrheal medication, prior abdominal surgery other than appendectomy or cholecystectomy, or enrollment in another trial.

Patients were started on ondansetron 4 mg/d with dose titration up to 24 mg/d based on response; no dose adjustments were allowed during the last two weeks of the study. There was a two- to three-week washout between treatment periods.

The primary endpoint was average stool consistency in the last two weeks of treatment, as measured by the Bristol Stool Form (BSF) scale.13 The BSF is a visual scale that depicts stool as hard (type 1) to watery (type 7); types 3 and 4 describe normal stools. The study also looked at urgency and frequency of defecation, bowel transit time, and pain scores.

Treatment with ondansetron resulted in a small but statistically significant improvement in stool consistency. The mean difference in BSF score between ondansetron and placebo was –0.9, indicating slightly more formed stool with use of ondansetron. Scores for IBS severity—mild (a score of 75 to 175 out of 500), moderate (175 to 300), or severe (> 300)—were reduced by more points with ondansetron than with placebo (83 ± 9.8 vs 37 ± 9.7, respectively). Although this mean difference of 46 points fell just short of the 50-point threshold that is considered clinically significant, many patients exceeded this threshold.

Compared to those who received placebo, patients who took ondansetron also had less frequent defecation and lower urgency scores. Gut transit time was lengthened in the ondansetron group by 10 hours more than in the placebo group.

Pain scores did not change significantly for patients taking ondansetron, although they experienced significantly fewer days of urgency and bloating. Symptoms typically improved in as little as seven days but returned after ondansetron use stopped (typically within two weeks). Sixty-five percent of patients reported adequate relief with ondansetron, compared to 14% with placebo.

Patients whose diarrhea was more severe at baseline didn’t respond as well to ondansetron as did those whose diarrhea was less severe. The only frequent adverse effect was constipation, which occurred in 9% of patients receiving ondansetron and 2% of those on placebo.

WHAT’S NEW

Another option for IBS-D

A prior, smaller study of ondansetron that used a lower dosage (12 mg/d) suggested benefit in IBS-D.14 In that study, ondansetron decreased diarrhea and functional dyspepsia. The study by Garsed et al1 is the first large RCT to show significantly improved stool consistency, less frequent defecation, and less urgency and bloating from using ondansetron to treat IBS-D.

CAVEATS

Ondansetron doesn’t appear to reduce pain

In Garsed et al,1 patients who received ondansetron did not experience relief from pain, which is one of the main complaints of IBS. However, this study did find slight improvement in formed stools, symptom relief that approached—but did not quite reach—clinical significance, fewer days with urgency and bloating, and less frequent defecation.

This study did not evaluate the long-term effects of ondansetron use. However, ondansetron has been used for other indications for more than 25 years and has been reported to have a low risk for adverse effects.15

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Remember ondansetron is not for IBS patients with constipation

Proper use of this drug among patients with IBS is key. The primary benefits of ondansetron are limited to IBS patients who have diarrhea, and not constipation. Ondansetron should not be prescribed to IBS patients who experience constipation or those with mixed symptoms.

REFERENCES

1. Garsed K, Chernova J, Hastings M, et al. A randomised trial of ondansetron for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea. Gut. 2014;63:1617-1625.

2. Hahn BA, Yan S, Strassels S. Impact of irritable bowel syndrome on quality of life and resource use in the United States and United Kingdom. Digestion. 1999;60:77-81.

3. Drossman DA, Dumitrascu DL. Rome III: new standard for functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006;15:237-241.

4. Luscombe FA. Health-related quality of life and associated psychosocial factors in irritable bowel syndrome: a review. Qual Life Res. 2000;9:161-176.

5. Saito YA, Locke GR, Talley NJ, et al. A comparison of the Rome and Manning criteria for case identification in epidemiological investigations of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2816-2824.

6. Thompson WG, Heaton KW, Smyth GT, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome in general practice: prevalence, characteristics, and referral. Gut. 2000;46:78-82.

7. Tillisch K, Labus JS, Naliboff BD, et al. Characterization of the alternating bowel habit subtype in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:896-904.

8. Schuster MM. Diagnostic evaluation of the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1991;20:269-278.

9. Sandler RS, Everhart JE, Donowitz M, et al. The burden of selected digestive diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1500-1511.

10. Talley NJ. Pharmacologic therapy for the irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:750-758.

11. Andresen V, Montori VM, Keller J, et al. Effects of 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) type 3 antagonists on symptom relief and constipation in nonconstipated irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:545-555.

12. Chang L, Chey WD, Harris L, et al. Incidence of ischemic colitis and serious complications of constipation among patients using alosetron: systematic review of clinical trials and post-marketing surveillance data. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1069-1079.

13. Heaton KW, O’Donnell LJ. An office guide to whole-gut transit time. Patients’ recollection of their stool form. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1994;19:28-30.

14. Maxton DG, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. Selective 5‐hydroxytryptamine antagonism: a role in irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10:595-599.

15. Gill SK, Einarson A. The safety of drugs for the treatment of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2007;6:685-694.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2014. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2014;63(10):600-602.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Consider prescribing ondansetron (up to 24 mg/d) for patients who have irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea (IBS-D).1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a well-done double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized controlled trial (RCT).1

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 23-year-old woman who was diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) comes to your clinic with complaints of increased frequency of defecation with watery stools and generalized, cramping abdominal pain. She also notes increased passage of mucus and a sensation of incomplete evacuation.

She says the only thing that relieves her pain is defecation. She has tried loperamide, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen without relief. She does not have Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis. What else can you offer her that is safe and effective?

IBS is a chronic, episodic functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort and altered bowel habits: constipation (IBS-C), diarrhea (IBS-D), or alternating periods of both—mixed (IBS-M).2 The diagnosis is based on Rome III criteria, which include recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort on at least three days per month in the past three months associated with two or more of the following: improvement with defecation, onset associated with a change in frequency of stool, and onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool.3 IBS often is unrecognized or untreated, and as few as 25% of patients with IBS seek care.4

IBS-D affects approximately 5% of the general population in North America.5,6 IBS-D is associated with a considerably decreased quality of life and is a common cause of work absenteeism.7,8 Because many conditions can cause diarrhea, patients typically undergo numerous tests before receiving an accurate diagnosis, which creates a financial burden.9

For many patients, current IBS treatments—including fiber supplements, laxatives, antidiarrheal medications, antispasmodics, and antidepressants such as tricyclics and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors—are unsatisfactory.10 Alosetron, a 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 (5-HT3) receptor antagonist, has been used to treat IBS-D,11 but this medication was voluntarily withdrawn from the US market in 2000 due to concerns about ischemic colitis and severe constipation.12 It was reintroduced in 2002 but can be prescribed only by clinicians who enroll in a prescribing program provided by the manufacturer, and there are restrictions on its use.

Ondansetron—another 5-HT3 receptor antagonist used to treat nausea and vomiting caused by chemotherapy—may be another option for treating IBS-D. Garsed et al1 recently conducted an RCT to evaluate the efficacy of ondansetron for patients with IBS-D.

Study summary >>

STUDY SUMMARY

Ondansetron improves stool consistency, severity of IBS symptoms

In a five-week, double-blind crossover RCT, Garsed et al1 compared ondansetron with placebo for symptom relief in 120 patients who met Rome III criteria for IBS-D. All patients were ages 18 to 75 and had no evidence of inflammatory bowel disease. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy or breastfeeding, unwillingness to stop antidiarrheal medication, prior abdominal surgery other than appendectomy or cholecystectomy, or enrollment in another trial.

Patients were started on ondansetron 4 mg/d with dose titration up to 24 mg/d based on response; no dose adjustments were allowed during the last two weeks of the study. There was a two- to three-week washout between treatment periods.

The primary endpoint was average stool consistency in the last two weeks of treatment, as measured by the Bristol Stool Form (BSF) scale.13 The BSF is a visual scale that depicts stool as hard (type 1) to watery (type 7); types 3 and 4 describe normal stools. The study also looked at urgency and frequency of defecation, bowel transit time, and pain scores.

Treatment with ondansetron resulted in a small but statistically significant improvement in stool consistency. The mean difference in BSF score between ondansetron and placebo was –0.9, indicating slightly more formed stool with use of ondansetron. Scores for IBS severity—mild (a score of 75 to 175 out of 500), moderate (175 to 300), or severe (> 300)—were reduced by more points with ondansetron than with placebo (83 ± 9.8 vs 37 ± 9.7, respectively). Although this mean difference of 46 points fell just short of the 50-point threshold that is considered clinically significant, many patients exceeded this threshold.

Compared to those who received placebo, patients who took ondansetron also had less frequent defecation and lower urgency scores. Gut transit time was lengthened in the ondansetron group by 10 hours more than in the placebo group.

Pain scores did not change significantly for patients taking ondansetron, although they experienced significantly fewer days of urgency and bloating. Symptoms typically improved in as little as seven days but returned after ondansetron use stopped (typically within two weeks). Sixty-five percent of patients reported adequate relief with ondansetron, compared to 14% with placebo.

Patients whose diarrhea was more severe at baseline didn’t respond as well to ondansetron as did those whose diarrhea was less severe. The only frequent adverse effect was constipation, which occurred in 9% of patients receiving ondansetron and 2% of those on placebo.

WHAT’S NEW

Another option for IBS-D

A prior, smaller study of ondansetron that used a lower dosage (12 mg/d) suggested benefit in IBS-D.14 In that study, ondansetron decreased diarrhea and functional dyspepsia. The study by Garsed et al1 is the first large RCT to show significantly improved stool consistency, less frequent defecation, and less urgency and bloating from using ondansetron to treat IBS-D.

CAVEATS

Ondansetron doesn’t appear to reduce pain

In Garsed et al,1 patients who received ondansetron did not experience relief from pain, which is one of the main complaints of IBS. However, this study did find slight improvement in formed stools, symptom relief that approached—but did not quite reach—clinical significance, fewer days with urgency and bloating, and less frequent defecation.

This study did not evaluate the long-term effects of ondansetron use. However, ondansetron has been used for other indications for more than 25 years and has been reported to have a low risk for adverse effects.15

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Remember ondansetron is not for IBS patients with constipation

Proper use of this drug among patients with IBS is key. The primary benefits of ondansetron are limited to IBS patients who have diarrhea, and not constipation. Ondansetron should not be prescribed to IBS patients who experience constipation or those with mixed symptoms.

REFERENCES

1. Garsed K, Chernova J, Hastings M, et al. A randomised trial of ondansetron for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea. Gut. 2014;63:1617-1625.

2. Hahn BA, Yan S, Strassels S. Impact of irritable bowel syndrome on quality of life and resource use in the United States and United Kingdom. Digestion. 1999;60:77-81.

3. Drossman DA, Dumitrascu DL. Rome III: new standard for functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006;15:237-241.

4. Luscombe FA. Health-related quality of life and associated psychosocial factors in irritable bowel syndrome: a review. Qual Life Res. 2000;9:161-176.

5. Saito YA, Locke GR, Talley NJ, et al. A comparison of the Rome and Manning criteria for case identification in epidemiological investigations of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2816-2824.

6. Thompson WG, Heaton KW, Smyth GT, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome in general practice: prevalence, characteristics, and referral. Gut. 2000;46:78-82.

7. Tillisch K, Labus JS, Naliboff BD, et al. Characterization of the alternating bowel habit subtype in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:896-904.

8. Schuster MM. Diagnostic evaluation of the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1991;20:269-278.

9. Sandler RS, Everhart JE, Donowitz M, et al. The burden of selected digestive diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1500-1511.

10. Talley NJ. Pharmacologic therapy for the irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:750-758.

11. Andresen V, Montori VM, Keller J, et al. Effects of 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) type 3 antagonists on symptom relief and constipation in nonconstipated irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:545-555.

12. Chang L, Chey WD, Harris L, et al. Incidence of ischemic colitis and serious complications of constipation among patients using alosetron: systematic review of clinical trials and post-marketing surveillance data. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1069-1079.

13. Heaton KW, O’Donnell LJ. An office guide to whole-gut transit time. Patients’ recollection of their stool form. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1994;19:28-30.

14. Maxton DG, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. Selective 5‐hydroxytryptamine antagonism: a role in irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10:595-599.

15. Gill SK, Einarson A. The safety of drugs for the treatment of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2007;6:685-694.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2014. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2014;63(10):600-602.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Consider prescribing ondansetron (up to 24 mg/d) for patients who have irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea (IBS-D).1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a well-done double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized controlled trial (RCT).1

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 23-year-old woman who was diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) comes to your clinic with complaints of increased frequency of defecation with watery stools and generalized, cramping abdominal pain. She also notes increased passage of mucus and a sensation of incomplete evacuation.

She says the only thing that relieves her pain is defecation. She has tried loperamide, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen without relief. She does not have Crohn disease or ulcerative colitis. What else can you offer her that is safe and effective?

IBS is a chronic, episodic functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort and altered bowel habits: constipation (IBS-C), diarrhea (IBS-D), or alternating periods of both—mixed (IBS-M).2 The diagnosis is based on Rome III criteria, which include recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort on at least three days per month in the past three months associated with two or more of the following: improvement with defecation, onset associated with a change in frequency of stool, and onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool.3 IBS often is unrecognized or untreated, and as few as 25% of patients with IBS seek care.4

IBS-D affects approximately 5% of the general population in North America.5,6 IBS-D is associated with a considerably decreased quality of life and is a common cause of work absenteeism.7,8 Because many conditions can cause diarrhea, patients typically undergo numerous tests before receiving an accurate diagnosis, which creates a financial burden.9

For many patients, current IBS treatments—including fiber supplements, laxatives, antidiarrheal medications, antispasmodics, and antidepressants such as tricyclics and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors—are unsatisfactory.10 Alosetron, a 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 (5-HT3) receptor antagonist, has been used to treat IBS-D,11 but this medication was voluntarily withdrawn from the US market in 2000 due to concerns about ischemic colitis and severe constipation.12 It was reintroduced in 2002 but can be prescribed only by clinicians who enroll in a prescribing program provided by the manufacturer, and there are restrictions on its use.

Ondansetron—another 5-HT3 receptor antagonist used to treat nausea and vomiting caused by chemotherapy—may be another option for treating IBS-D. Garsed et al1 recently conducted an RCT to evaluate the efficacy of ondansetron for patients with IBS-D.

Study summary >>

STUDY SUMMARY

Ondansetron improves stool consistency, severity of IBS symptoms

In a five-week, double-blind crossover RCT, Garsed et al1 compared ondansetron with placebo for symptom relief in 120 patients who met Rome III criteria for IBS-D. All patients were ages 18 to 75 and had no evidence of inflammatory bowel disease. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy or breastfeeding, unwillingness to stop antidiarrheal medication, prior abdominal surgery other than appendectomy or cholecystectomy, or enrollment in another trial.

Patients were started on ondansetron 4 mg/d with dose titration up to 24 mg/d based on response; no dose adjustments were allowed during the last two weeks of the study. There was a two- to three-week washout between treatment periods.

The primary endpoint was average stool consistency in the last two weeks of treatment, as measured by the Bristol Stool Form (BSF) scale.13 The BSF is a visual scale that depicts stool as hard (type 1) to watery (type 7); types 3 and 4 describe normal stools. The study also looked at urgency and frequency of defecation, bowel transit time, and pain scores.

Treatment with ondansetron resulted in a small but statistically significant improvement in stool consistency. The mean difference in BSF score between ondansetron and placebo was –0.9, indicating slightly more formed stool with use of ondansetron. Scores for IBS severity—mild (a score of 75 to 175 out of 500), moderate (175 to 300), or severe (> 300)—were reduced by more points with ondansetron than with placebo (83 ± 9.8 vs 37 ± 9.7, respectively). Although this mean difference of 46 points fell just short of the 50-point threshold that is considered clinically significant, many patients exceeded this threshold.

Compared to those who received placebo, patients who took ondansetron also had less frequent defecation and lower urgency scores. Gut transit time was lengthened in the ondansetron group by 10 hours more than in the placebo group.

Pain scores did not change significantly for patients taking ondansetron, although they experienced significantly fewer days of urgency and bloating. Symptoms typically improved in as little as seven days but returned after ondansetron use stopped (typically within two weeks). Sixty-five percent of patients reported adequate relief with ondansetron, compared to 14% with placebo.

Patients whose diarrhea was more severe at baseline didn’t respond as well to ondansetron as did those whose diarrhea was less severe. The only frequent adverse effect was constipation, which occurred in 9% of patients receiving ondansetron and 2% of those on placebo.

WHAT’S NEW

Another option for IBS-D

A prior, smaller study of ondansetron that used a lower dosage (12 mg/d) suggested benefit in IBS-D.14 In that study, ondansetron decreased diarrhea and functional dyspepsia. The study by Garsed et al1 is the first large RCT to show significantly improved stool consistency, less frequent defecation, and less urgency and bloating from using ondansetron to treat IBS-D.

CAVEATS

Ondansetron doesn’t appear to reduce pain

In Garsed et al,1 patients who received ondansetron did not experience relief from pain, which is one of the main complaints of IBS. However, this study did find slight improvement in formed stools, symptom relief that approached—but did not quite reach—clinical significance, fewer days with urgency and bloating, and less frequent defecation.

This study did not evaluate the long-term effects of ondansetron use. However, ondansetron has been used for other indications for more than 25 years and has been reported to have a low risk for adverse effects.15

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Remember ondansetron is not for IBS patients with constipation

Proper use of this drug among patients with IBS is key. The primary benefits of ondansetron are limited to IBS patients who have diarrhea, and not constipation. Ondansetron should not be prescribed to IBS patients who experience constipation or those with mixed symptoms.

REFERENCES

1. Garsed K, Chernova J, Hastings M, et al. A randomised trial of ondansetron for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea. Gut. 2014;63:1617-1625.

2. Hahn BA, Yan S, Strassels S. Impact of irritable bowel syndrome on quality of life and resource use in the United States and United Kingdom. Digestion. 1999;60:77-81.

3. Drossman DA, Dumitrascu DL. Rome III: new standard for functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006;15:237-241.

4. Luscombe FA. Health-related quality of life and associated psychosocial factors in irritable bowel syndrome: a review. Qual Life Res. 2000;9:161-176.

5. Saito YA, Locke GR, Talley NJ, et al. A comparison of the Rome and Manning criteria for case identification in epidemiological investigations of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2816-2824.

6. Thompson WG, Heaton KW, Smyth GT, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome in general practice: prevalence, characteristics, and referral. Gut. 2000;46:78-82.

7. Tillisch K, Labus JS, Naliboff BD, et al. Characterization of the alternating bowel habit subtype in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:896-904.

8. Schuster MM. Diagnostic evaluation of the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1991;20:269-278.

9. Sandler RS, Everhart JE, Donowitz M, et al. The burden of selected digestive diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1500-1511.

10. Talley NJ. Pharmacologic therapy for the irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:750-758.

11. Andresen V, Montori VM, Keller J, et al. Effects of 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) type 3 antagonists on symptom relief and constipation in nonconstipated irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:545-555.

12. Chang L, Chey WD, Harris L, et al. Incidence of ischemic colitis and serious complications of constipation among patients using alosetron: systematic review of clinical trials and post-marketing surveillance data. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1069-1079.

13. Heaton KW, O’Donnell LJ. An office guide to whole-gut transit time. Patients’ recollection of their stool form. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1994;19:28-30.

14. Maxton DG, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. Selective 5‐hydroxytryptamine antagonism: a role in irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10:595-599.

15. Gill SK, Einarson A. The safety of drugs for the treatment of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2007;6:685-694.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2014. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2014;63(10):600-602.

An antiemetic for irritable bowel syndrome?

Consider prescribing ondansetron up to 24 mg/d for patients who have irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea (IBS-D).1

Strength of recommendation

B: Based on a well-done double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Garsed K, Chernova J, Hastings M, et al. A randomised trial of ondansetron for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea. Gut. 2014;63:1617-1625.

Illustrative case

A 23-year-old woman who was diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) comes to your clinic with complaints of increased frequency of defecation with watery stools and generalized, cramping abdominal pain. She also notes increased passage of mucus and a sensation of incomplete evacuation. She says the only thing that relieves her pain is defecation. She has tried loperamide, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen without relief. She does not have Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. What else can you offer her that is safe and effective?

IBS is a chronic, episodic functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort and altered bowel habits (constipation [IBS-C], diarrhea [IBS-D], or alternating periods of both—mixed [IBS-M]).2 It is diagnosed based on Rome III criteria—recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort at least 3 days/month in the last 3 months associated with ≥2 of the following: improvement with defecation, onset associated with a change in frequency of stool, and onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool.3 IBS often is unrecognized or untreated, and as few as 25% of patients with IBS seek care.4

IBS-D affects approximately 5% of the general population in North America.5,6 IBS-D is associated with a considerably decreased quality of life and is a common cause of work absenteeism.7,8 Because many conditions can cause diarrhea, patients typically undergo numerous tests before receiving an accurate diagnosis, which creates a financial burden.9

For many patients, current IBS treatments, which include fiber supplements, laxatives, antidiarrheal medications, antispasmodics, and antidepressants such as tricyclics and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, are unsatisfactory.10 Alosetron, a 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 (5HT3) receptor antagonist, has been used to treat IBS-D,11 but this medication was voluntarily withdrawn from the US market in 2000 due to concerns of ischemic colitis and severe constipation.12 It was reintroduced in 2002, but can be prescribed only by physicians who enroll in a prescribing program provided by the manufacturer, and the drug has restrictions on its use.

Ondansetron—a different 5HT3 receptor antagonist used to treat nausea and vomiting caused by chemotherapy—may be another option for treating IBS-D. Garsed et al1 recently conducted a RCT to evaluate the efficacy of ondansetron for patients with IBS-D.

STUDY SUMMARY: Ondansetron improves stool consistency, severity of IBS symptoms

In a 5-week, double-blind crossover RCT, Garsed et al1 compared ondansetron vs placebo for symptom relief in 120 patients who met Rome III criteria for IBS-D. All patients were ages 18 to 75 and had no evidence of inflammatory bowel disease. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy or breastfeeding, unwillingness to stop antidiarrheal medication, prior abdominal surgery other than appendectomy or cholecystectomy, or being in another trial. Patients were started on ondansetron 4 mg/d with dose titration up to 24 mg/d based on response; no dose adjustments were allowed during the last 2 weeks of the study. There was a 2- to 3-week washout between treatment periods.

The primary endpoint was average stool consistency in the last 2 weeks of treatment, as measured by the Bristol Stool Form (BSF) scale.13 The BSF is a visual scale that depicts stool as hard (Type 1) to watery (Type 7); types 3 and 4 describe normal stools. The study also looked at urgency and frequency of defecation, bowel transit time, and pain scores.

Treatment with ondansetron resulted in a small but statistically significant improvement in stool consistency. The mean difference in BSF score between ondansetron and placebo was -0.9 (95% confidence interval [CI], -1.1 to -0.6; P<.001), indicating slightly more formed stool with use of ondansetron. The IBS Severity Scoring System score (maximum score 500 points, with mild, moderate, and severe cases indicated by scores of 75-175, 175-300, and >300, respectively) was reduced by more points with ondansetron than placebo (83 ± 9.8 vs 37 ± 9.7; P=.001). Although this mean difference of 46 points fell just short of the 50-point threshold that is considered clinically significant, many patients exceeded this threshold.

Compared to those who received placebo, patients who took ondansetron also had less frequent defecation (P=.002) and lower urgency scores (P<.001). Gut transit time was lengthened in the ondansetron group by 10 hours more than in the placebo group (95% CI, 6-14 hours; P<.001). Pain scores did not change significantly for patients taking ondansetron, although they experienced significantly fewer days of urgency and bloating. Symptoms typically improved in as little as 7 days but returned after stopping ondansetron, typically within 2 weeks. Sixty-five percent of patients reported adequate relief with ondansetron, compared to 14% with placebo.

Patients whose diarrhea was more severe at baseline didn’t respond as well to ondansetron as did those whose diarrhea was less severe. The only frequent adverse effect was constipation, which occurred in 9% of patients receiving ondansetron and 2% of those on placebo.

WHAT’S NEW: Another option for IBS patients with diarrhea

A prior, smaller study of ondansetron that used a lower dosage (12 mg/d) suggested benefit in IBS-D.14 In that study, ondansetron decreased diarrhea and functional dyspepsia. The study by Garsed et al1 is the first large RCT to show significantly improved stool consistency, less frequent defecation, and less urgency and bloating from using ondansetron to treat IBS-D.

CAVEATS: Ondansetron doesn’t appear to reduce pain

In Garsed et al,1 patients who received ondansetron did not experience relief from pain, which is one of the main complaints of IBS. However, this study did find slight improvement in formed stools, symptom relief that approached—but did not quite reach—clinical significance, fewer days with urgency and bloating, and less frequent defecation. This study did not evaluate the long-term effects of ondansetron use. However, ondansetron has been used for other indications for more than 25 years and has been reported to have a low risk of adverse effects.15

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION: Remember ondansetron is not for IBS patients with constipation

Proper use of this drug among patients with IBS is key. The primary benefits of ondansetron are limited to IBS patients who suffer from diarrhea, and not constipation. Ondansetron should not be prescribed to IBS patients who experience constipation, or those with mixed symptoms.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Click here to view PURL METHODOLOGY

1. Garsed K, Chernova J, Hastings M, et al. A randomised trial of ondansetron for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea. Gut. 2014;63:1617-1625.

2. Hahn BA, Yan S, Strassels S. Impact of irritable bowel syndrome on quality of life and resource use in the United States and United Kingdom. Digestion. 1999;60:77-81.

3. Drossman DA, Dumitrascu DL. Rome III: New standard for functional gastrointestinal disorders. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006;15:237-241.

4. Luscombe FA. Health-related quality of life and associated psychosocial factors in irritable bowel syndrome: a review. Qual Life Res. 2000;9:161-176.

5. Saito YA, Locke GR, Talley NJ, et al. A comparison of the Rome and Manning criteria for case identification in epidemiological investigations of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2816-2824.

6. Thompson WG, Heaton KW, Smyth GT, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome in general practice: prevalence, characteristics, and referral. Gut. 2000;46:78-82.

7. Tillisch K, Labus JS, Naliboff BD, et al. Characterization of the alternating bowel habit subtype in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:896-904.