User login

Bullous Eruption Caused by an Exotic Hedgehog Purchased as a Household Pet

Case Report

A 37-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with an itchy rash involving the right hand. The rash had been present for 10 days but had become increasingly pruritic and vesicular over the last 5 days. She denied new exposures or other household members with similar symptoms. The patient reported that she had purchased a 4-toed, white-bellied African pygmy hedgehog (Atelerix albiventris) approximately 4 months prior. Upon questioning, she stated that she handled the hedgehog a couple of times a week and always washed her hands with soap and water immediately after. The patient’s medical and personal history were otherwise unremarkable.

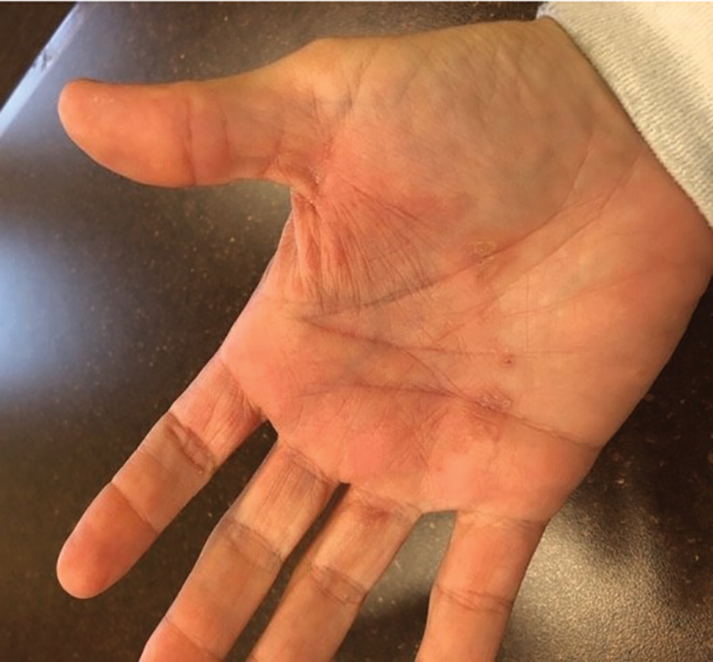

Review of systems, including fevers, chills, and night sweats, was negative. Clinical examination revealed erythema with overlying vesicles and pustules on the right radial palm, radial dorsal hand, and interdigital web space of the first and second digit (Figure 1). The eruption was actively discharging serous exudate. No other lesions were present.

Unspecified acute contact dermatitis was the preliminary diagnosis based on clinical presentation and history. Other entities considered before making the diagnosis included psoriasis, eczema, and an infectious cause. Specimens were taken for bacterial and fungal cultures as well as a specimen for herpes simplex virus by polymerase chain reaction. Due to the intense pruritus and vesicular nature of the rash, the patient was treatedwith a 2-week, 60-40-20 prednisone taper and clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily.

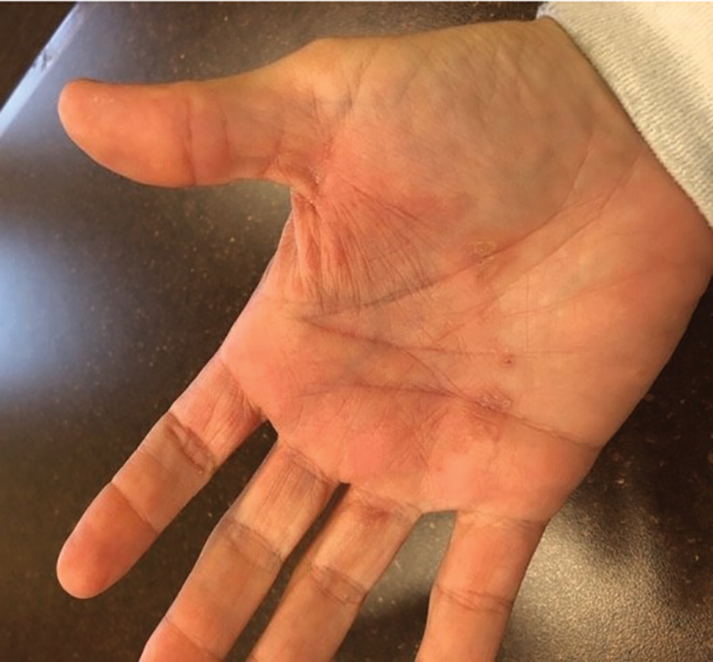

At 1-week follow-up, the eruption had improved, but the patient was still experiencing mild pruritus. Physical examination of the affected areas showed erythematous, violaceous, annular patches with slight scale at the periphery; all bullous lesions had resolved (Figure 2). Bacterial culture and herpes simplex virus by polymerase chain reaction were negative.

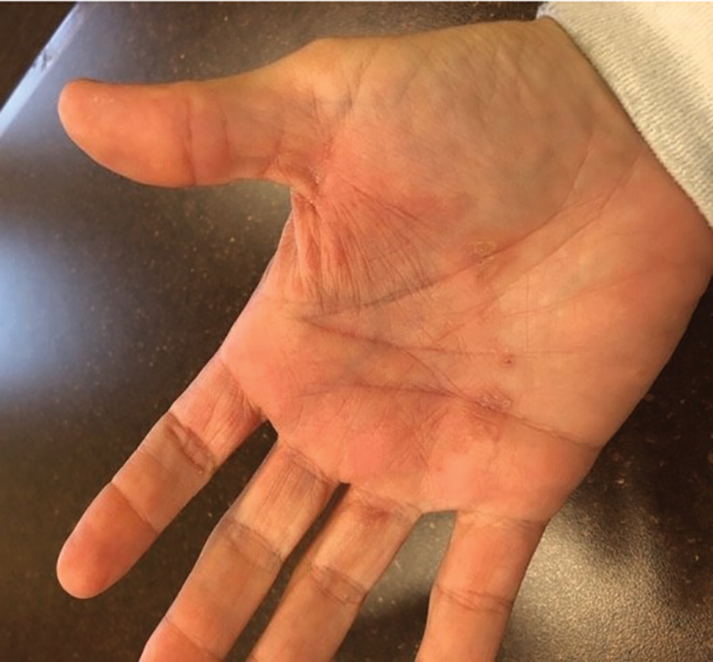

Two weeks after initial consultation, the fungal culture returned positive and showed growth of Trichophyton mentagrophytes. The patient was contacted and returned for re-evaluation. Physical examination showed decreased erythema and no bullous lesions; however, there was increased fine scale throughout the affected area on the right palm and first and second interdigital spaces (Figure 3). She reported mild pruritus. A confirmatory potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was positive for fungal hyphae. The patient was subsequently diagnosed with bullous tinea secondary to domestic hedgehog exposure that was now presenting as tinea manuum incognita. After 2 weeks of appropriate systemic and topical antifungal therapy, the patient’s skin eruption markedly improved (Figure 4).

Comment

Tinea manuum is a dermatophytic epidermal infection of the hand. The most common causative organisms are Trichophyton rubrum, T mentagrophytes, and Epidermophyton floccosum. Infection can be acquired from contact with an infected person or animal, fomites, soil, or autoinoculation. Tinea manuum often is associated with tinea pedis. The hand that is used to excoriate the pruritic feet becomes infected, resulting in the classic two feet–one hand syndrome, which this patient did not have.1

Dermatophytes colonize keratin-containing tissues—skin, hair, and nails—utilizing the keratin for nutrients, and they do not invade living tissue in immunocompetent hosts. Dermatophytes cause clinical disease from an allergic host response to fungal antigens or their metabolic products.1 Tinea incognito results from the use of corticosteroids to treat a cutaneous fungal infection. The immunomodulatory effects of corticosteroids alter the appearance of the lesion. Hallmark signs and symptoms of a tinea infection, including scale, prominent border, erythema, and pruritus, can be reduced with corticosteroid use, giving the false impression that the lesion is resolving.2,3

The diagnosis of tinea manuum can be made clinically and often is supported with the findings of a KOH preparation. Scraping from an active scaling border generally provides the best results for obtaining fungal elements. For vesiculobullous lesions, the roof of a vesicle can provide an adequate specimen. Fungal culture and specific dermatophyte testing mediums can be used as confirmatory tests or allow for speciation, which help establish the diagnosis.1

Trichophyton mentagrophytes is a species complex—a group of closely related organisms that share morphologic appearance to the point that boundaries between them often are unclear. It can be identified by gross and microscopic morphology; however, variants of T mentagrophytes (eg, Trichophyton interdigitale, Trichophyton erinacei) require a confirmatory test or molecular analysis to be correctly identified.4-6 The laboratory used at our facility does not routinely attempt to identify the variant due to of lack of clinical significance.7,8

Anthropophilic fungi such as T rubrum, E floccosum, and T interdigitale generally do not cause a robust immunologic reaction. Infection usually is chronic in nature, though cases of pustular and vesicular tinea have been described.9,10Trichophyton erinacei and T mentagrophytes are zoophilic dermatophytes that cause an acute host response and are more likely to present with vesiculobullous lesions. Trichophyton erinacei is the most common fungal pathogen associated with A albiventris and has been isolated from its epidermal mites and quills,11,12 which likely facilitates interspecies transmission and compromises the cutaneous barrier of human hosts when the hedgehog is handled.

Atelerix albiventris is the most common domesticated hedgehog in the United States. These mild-mannered, nocturnal insectivores are unique, low-maintenance pets that have recently gained popularity. They are notable for their propensity to curl into a ball when frightened (Figure 5). The spines are not barbed and do not detach, as those of a porcupine do, but are still capable of piercing the skin. Atelerix albiventris is known to cause zoonotic dermatosis in humans and should be handled with gloves.13 Performing a KOH preparation early in the diagnostic workup can help initiate antifungal therapy, as results of fungal culture can take several weeks.

Conclusion

This case illustrates the importance of close follow-up of skin lesions that only partially respond to initial treatment and maintaining a high index of suspicion as exotic pets become popular.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Hunt KM, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1329-1363.

- Habif T. Superficial fungal infections. In: Habif T. Clinical Dermatology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:487-533.

- Lange M, Jasiel‐Walikowska E, Nowicki R, et al. Tinea incognito due to Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Mycoses. 2010;53:455-457.

- Pchelin IM, Azarov DV, Churina MA, et al. Species boundaries in the Trichophyton mentagrophytes/T. interdigitale species complex. Med Mycol. 2019;57:781-789.

- Makimura K, Mochizuki T, Hasegawa A, et al. Phylogenetic classification of Trichophyton mentagrophytes complex strains based on DNA sequences of nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer 1 regions. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2629-2633.

- de Hoog GS, Dukik K, Monod M, et al. Toward a novel multilocus phylogenetic taxonomy for the dermatophytes. Mycopathologia. 2017;182:5-31.

- Rudramurthy SM, Shankarnarayan SA, Dogra S, et al. Mutation in the squalene epoxidase gene of Trichophyton interdigitale and Trichophyton rubrum associated with allylamine resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62:e02522-17.

- Singh A, Masih A, Khurana A, et al. High terbinafine resistance in Trichophyton interdigitale isolates in Delhi, India harbouring mutations in the squalene epoxidase gene. Mycoses. 2018;61:477-484.

- Kawakami Y, Oyama N, Sakai E, et al. Childhood tinea incognito caused by Trichophyton mentagrophytes var. interdigitale mimicking pustular psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:738-739.

- Neri I, Piraccini BM, Guareschi E, et al. Bullous tinea pedis in two children. Mycoses. 2004;47:475-478.

- Abarca ML, Castellá G, Martorell J, et al. Trichophyton erinacei in pet hedgehogs in Spain: occurrence and revision of its taxonomic status. Med Mycol. 2016;55:164-172.

- Morris P, English MP. Transmission and course of Trichophyton erinacei infections in British hedgehogs. Sabouraudia. 1973;11:42-47.

- Riley PY, Chomel BB. Hedgehog zoonoses. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1-5.

Case Report

A 37-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with an itchy rash involving the right hand. The rash had been present for 10 days but had become increasingly pruritic and vesicular over the last 5 days. She denied new exposures or other household members with similar symptoms. The patient reported that she had purchased a 4-toed, white-bellied African pygmy hedgehog (Atelerix albiventris) approximately 4 months prior. Upon questioning, she stated that she handled the hedgehog a couple of times a week and always washed her hands with soap and water immediately after. The patient’s medical and personal history were otherwise unremarkable.

Review of systems, including fevers, chills, and night sweats, was negative. Clinical examination revealed erythema with overlying vesicles and pustules on the right radial palm, radial dorsal hand, and interdigital web space of the first and second digit (Figure 1). The eruption was actively discharging serous exudate. No other lesions were present.

Unspecified acute contact dermatitis was the preliminary diagnosis based on clinical presentation and history. Other entities considered before making the diagnosis included psoriasis, eczema, and an infectious cause. Specimens were taken for bacterial and fungal cultures as well as a specimen for herpes simplex virus by polymerase chain reaction. Due to the intense pruritus and vesicular nature of the rash, the patient was treatedwith a 2-week, 60-40-20 prednisone taper and clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily.

At 1-week follow-up, the eruption had improved, but the patient was still experiencing mild pruritus. Physical examination of the affected areas showed erythematous, violaceous, annular patches with slight scale at the periphery; all bullous lesions had resolved (Figure 2). Bacterial culture and herpes simplex virus by polymerase chain reaction were negative.

Two weeks after initial consultation, the fungal culture returned positive and showed growth of Trichophyton mentagrophytes. The patient was contacted and returned for re-evaluation. Physical examination showed decreased erythema and no bullous lesions; however, there was increased fine scale throughout the affected area on the right palm and first and second interdigital spaces (Figure 3). She reported mild pruritus. A confirmatory potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was positive for fungal hyphae. The patient was subsequently diagnosed with bullous tinea secondary to domestic hedgehog exposure that was now presenting as tinea manuum incognita. After 2 weeks of appropriate systemic and topical antifungal therapy, the patient’s skin eruption markedly improved (Figure 4).

Comment

Tinea manuum is a dermatophytic epidermal infection of the hand. The most common causative organisms are Trichophyton rubrum, T mentagrophytes, and Epidermophyton floccosum. Infection can be acquired from contact with an infected person or animal, fomites, soil, or autoinoculation. Tinea manuum often is associated with tinea pedis. The hand that is used to excoriate the pruritic feet becomes infected, resulting in the classic two feet–one hand syndrome, which this patient did not have.1

Dermatophytes colonize keratin-containing tissues—skin, hair, and nails—utilizing the keratin for nutrients, and they do not invade living tissue in immunocompetent hosts. Dermatophytes cause clinical disease from an allergic host response to fungal antigens or their metabolic products.1 Tinea incognito results from the use of corticosteroids to treat a cutaneous fungal infection. The immunomodulatory effects of corticosteroids alter the appearance of the lesion. Hallmark signs and symptoms of a tinea infection, including scale, prominent border, erythema, and pruritus, can be reduced with corticosteroid use, giving the false impression that the lesion is resolving.2,3

The diagnosis of tinea manuum can be made clinically and often is supported with the findings of a KOH preparation. Scraping from an active scaling border generally provides the best results for obtaining fungal elements. For vesiculobullous lesions, the roof of a vesicle can provide an adequate specimen. Fungal culture and specific dermatophyte testing mediums can be used as confirmatory tests or allow for speciation, which help establish the diagnosis.1

Trichophyton mentagrophytes is a species complex—a group of closely related organisms that share morphologic appearance to the point that boundaries between them often are unclear. It can be identified by gross and microscopic morphology; however, variants of T mentagrophytes (eg, Trichophyton interdigitale, Trichophyton erinacei) require a confirmatory test or molecular analysis to be correctly identified.4-6 The laboratory used at our facility does not routinely attempt to identify the variant due to of lack of clinical significance.7,8

Anthropophilic fungi such as T rubrum, E floccosum, and T interdigitale generally do not cause a robust immunologic reaction. Infection usually is chronic in nature, though cases of pustular and vesicular tinea have been described.9,10Trichophyton erinacei and T mentagrophytes are zoophilic dermatophytes that cause an acute host response and are more likely to present with vesiculobullous lesions. Trichophyton erinacei is the most common fungal pathogen associated with A albiventris and has been isolated from its epidermal mites and quills,11,12 which likely facilitates interspecies transmission and compromises the cutaneous barrier of human hosts when the hedgehog is handled.

Atelerix albiventris is the most common domesticated hedgehog in the United States. These mild-mannered, nocturnal insectivores are unique, low-maintenance pets that have recently gained popularity. They are notable for their propensity to curl into a ball when frightened (Figure 5). The spines are not barbed and do not detach, as those of a porcupine do, but are still capable of piercing the skin. Atelerix albiventris is known to cause zoonotic dermatosis in humans and should be handled with gloves.13 Performing a KOH preparation early in the diagnostic workup can help initiate antifungal therapy, as results of fungal culture can take several weeks.

Conclusion

This case illustrates the importance of close follow-up of skin lesions that only partially respond to initial treatment and maintaining a high index of suspicion as exotic pets become popular.

Case Report

A 37-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with an itchy rash involving the right hand. The rash had been present for 10 days but had become increasingly pruritic and vesicular over the last 5 days. She denied new exposures or other household members with similar symptoms. The patient reported that she had purchased a 4-toed, white-bellied African pygmy hedgehog (Atelerix albiventris) approximately 4 months prior. Upon questioning, she stated that she handled the hedgehog a couple of times a week and always washed her hands with soap and water immediately after. The patient’s medical and personal history were otherwise unremarkable.

Review of systems, including fevers, chills, and night sweats, was negative. Clinical examination revealed erythema with overlying vesicles and pustules on the right radial palm, radial dorsal hand, and interdigital web space of the first and second digit (Figure 1). The eruption was actively discharging serous exudate. No other lesions were present.

Unspecified acute contact dermatitis was the preliminary diagnosis based on clinical presentation and history. Other entities considered before making the diagnosis included psoriasis, eczema, and an infectious cause. Specimens were taken for bacterial and fungal cultures as well as a specimen for herpes simplex virus by polymerase chain reaction. Due to the intense pruritus and vesicular nature of the rash, the patient was treatedwith a 2-week, 60-40-20 prednisone taper and clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% twice daily.

At 1-week follow-up, the eruption had improved, but the patient was still experiencing mild pruritus. Physical examination of the affected areas showed erythematous, violaceous, annular patches with slight scale at the periphery; all bullous lesions had resolved (Figure 2). Bacterial culture and herpes simplex virus by polymerase chain reaction were negative.

Two weeks after initial consultation, the fungal culture returned positive and showed growth of Trichophyton mentagrophytes. The patient was contacted and returned for re-evaluation. Physical examination showed decreased erythema and no bullous lesions; however, there was increased fine scale throughout the affected area on the right palm and first and second interdigital spaces (Figure 3). She reported mild pruritus. A confirmatory potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation was positive for fungal hyphae. The patient was subsequently diagnosed with bullous tinea secondary to domestic hedgehog exposure that was now presenting as tinea manuum incognita. After 2 weeks of appropriate systemic and topical antifungal therapy, the patient’s skin eruption markedly improved (Figure 4).

Comment

Tinea manuum is a dermatophytic epidermal infection of the hand. The most common causative organisms are Trichophyton rubrum, T mentagrophytes, and Epidermophyton floccosum. Infection can be acquired from contact with an infected person or animal, fomites, soil, or autoinoculation. Tinea manuum often is associated with tinea pedis. The hand that is used to excoriate the pruritic feet becomes infected, resulting in the classic two feet–one hand syndrome, which this patient did not have.1

Dermatophytes colonize keratin-containing tissues—skin, hair, and nails—utilizing the keratin for nutrients, and they do not invade living tissue in immunocompetent hosts. Dermatophytes cause clinical disease from an allergic host response to fungal antigens or their metabolic products.1 Tinea incognito results from the use of corticosteroids to treat a cutaneous fungal infection. The immunomodulatory effects of corticosteroids alter the appearance of the lesion. Hallmark signs and symptoms of a tinea infection, including scale, prominent border, erythema, and pruritus, can be reduced with corticosteroid use, giving the false impression that the lesion is resolving.2,3

The diagnosis of tinea manuum can be made clinically and often is supported with the findings of a KOH preparation. Scraping from an active scaling border generally provides the best results for obtaining fungal elements. For vesiculobullous lesions, the roof of a vesicle can provide an adequate specimen. Fungal culture and specific dermatophyte testing mediums can be used as confirmatory tests or allow for speciation, which help establish the diagnosis.1

Trichophyton mentagrophytes is a species complex—a group of closely related organisms that share morphologic appearance to the point that boundaries between them often are unclear. It can be identified by gross and microscopic morphology; however, variants of T mentagrophytes (eg, Trichophyton interdigitale, Trichophyton erinacei) require a confirmatory test or molecular analysis to be correctly identified.4-6 The laboratory used at our facility does not routinely attempt to identify the variant due to of lack of clinical significance.7,8

Anthropophilic fungi such as T rubrum, E floccosum, and T interdigitale generally do not cause a robust immunologic reaction. Infection usually is chronic in nature, though cases of pustular and vesicular tinea have been described.9,10Trichophyton erinacei and T mentagrophytes are zoophilic dermatophytes that cause an acute host response and are more likely to present with vesiculobullous lesions. Trichophyton erinacei is the most common fungal pathogen associated with A albiventris and has been isolated from its epidermal mites and quills,11,12 which likely facilitates interspecies transmission and compromises the cutaneous barrier of human hosts when the hedgehog is handled.

Atelerix albiventris is the most common domesticated hedgehog in the United States. These mild-mannered, nocturnal insectivores are unique, low-maintenance pets that have recently gained popularity. They are notable for their propensity to curl into a ball when frightened (Figure 5). The spines are not barbed and do not detach, as those of a porcupine do, but are still capable of piercing the skin. Atelerix albiventris is known to cause zoonotic dermatosis in humans and should be handled with gloves.13 Performing a KOH preparation early in the diagnostic workup can help initiate antifungal therapy, as results of fungal culture can take several weeks.

Conclusion

This case illustrates the importance of close follow-up of skin lesions that only partially respond to initial treatment and maintaining a high index of suspicion as exotic pets become popular.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Hunt KM, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1329-1363.

- Habif T. Superficial fungal infections. In: Habif T. Clinical Dermatology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:487-533.

- Lange M, Jasiel‐Walikowska E, Nowicki R, et al. Tinea incognito due to Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Mycoses. 2010;53:455-457.

- Pchelin IM, Azarov DV, Churina MA, et al. Species boundaries in the Trichophyton mentagrophytes/T. interdigitale species complex. Med Mycol. 2019;57:781-789.

- Makimura K, Mochizuki T, Hasegawa A, et al. Phylogenetic classification of Trichophyton mentagrophytes complex strains based on DNA sequences of nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer 1 regions. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2629-2633.

- de Hoog GS, Dukik K, Monod M, et al. Toward a novel multilocus phylogenetic taxonomy for the dermatophytes. Mycopathologia. 2017;182:5-31.

- Rudramurthy SM, Shankarnarayan SA, Dogra S, et al. Mutation in the squalene epoxidase gene of Trichophyton interdigitale and Trichophyton rubrum associated with allylamine resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62:e02522-17.

- Singh A, Masih A, Khurana A, et al. High terbinafine resistance in Trichophyton interdigitale isolates in Delhi, India harbouring mutations in the squalene epoxidase gene. Mycoses. 2018;61:477-484.

- Kawakami Y, Oyama N, Sakai E, et al. Childhood tinea incognito caused by Trichophyton mentagrophytes var. interdigitale mimicking pustular psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:738-739.

- Neri I, Piraccini BM, Guareschi E, et al. Bullous tinea pedis in two children. Mycoses. 2004;47:475-478.

- Abarca ML, Castellá G, Martorell J, et al. Trichophyton erinacei in pet hedgehogs in Spain: occurrence and revision of its taxonomic status. Med Mycol. 2016;55:164-172.

- Morris P, English MP. Transmission and course of Trichophyton erinacei infections in British hedgehogs. Sabouraudia. 1973;11:42-47.

- Riley PY, Chomel BB. Hedgehog zoonoses. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1-5.

- Elewski BE, Hughey LC, Hunt KM, et al. Fungal diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1329-1363.

- Habif T. Superficial fungal infections. In: Habif T. Clinical Dermatology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:487-533.

- Lange M, Jasiel‐Walikowska E, Nowicki R, et al. Tinea incognito due to Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Mycoses. 2010;53:455-457.

- Pchelin IM, Azarov DV, Churina MA, et al. Species boundaries in the Trichophyton mentagrophytes/T. interdigitale species complex. Med Mycol. 2019;57:781-789.

- Makimura K, Mochizuki T, Hasegawa A, et al. Phylogenetic classification of Trichophyton mentagrophytes complex strains based on DNA sequences of nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer 1 regions. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2629-2633.

- de Hoog GS, Dukik K, Monod M, et al. Toward a novel multilocus phylogenetic taxonomy for the dermatophytes. Mycopathologia. 2017;182:5-31.

- Rudramurthy SM, Shankarnarayan SA, Dogra S, et al. Mutation in the squalene epoxidase gene of Trichophyton interdigitale and Trichophyton rubrum associated with allylamine resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62:e02522-17.

- Singh A, Masih A, Khurana A, et al. High terbinafine resistance in Trichophyton interdigitale isolates in Delhi, India harbouring mutations in the squalene epoxidase gene. Mycoses. 2018;61:477-484.

- Kawakami Y, Oyama N, Sakai E, et al. Childhood tinea incognito caused by Trichophyton mentagrophytes var. interdigitale mimicking pustular psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:738-739.

- Neri I, Piraccini BM, Guareschi E, et al. Bullous tinea pedis in two children. Mycoses. 2004;47:475-478.

- Abarca ML, Castellá G, Martorell J, et al. Trichophyton erinacei in pet hedgehogs in Spain: occurrence and revision of its taxonomic status. Med Mycol. 2016;55:164-172.

- Morris P, English MP. Transmission and course of Trichophyton erinacei infections in British hedgehogs. Sabouraudia. 1973;11:42-47.

- Riley PY, Chomel BB. Hedgehog zoonoses. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1-5.

Practice Points

- Bullous tinea may present with little or no scale, which can lead to confusion with acute contact dermatitis.

- The recent popularity of exotic pets may increase the incidence of fungal zoonotic dermatitis.

- Prompt recognition of tinea incognito is essential when treating lesions with corticosteroids.

- Skin lesions not responding appropriately to therapy warrant reassessment and further evaluation.

Erythematous Pruritic Plaque on the Cheek

The Diagnosis: Tinea Faciei

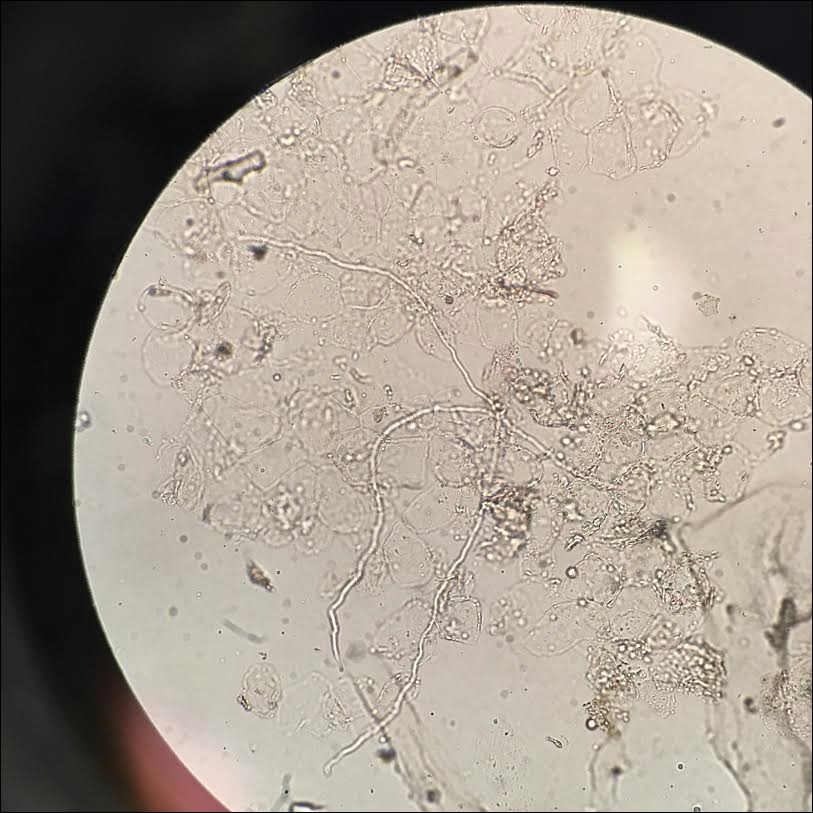

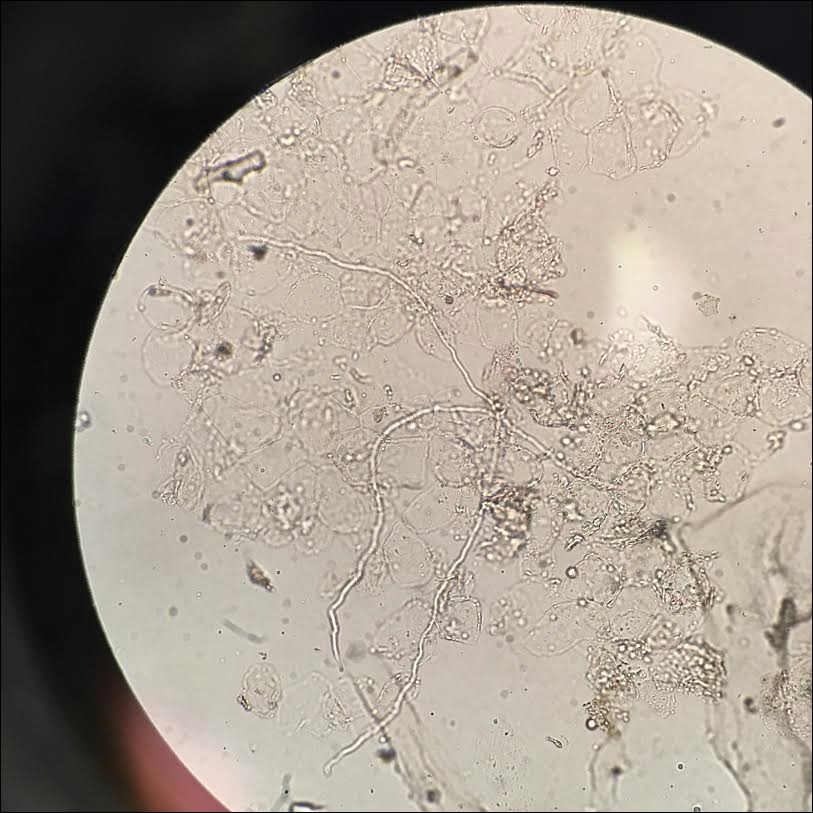

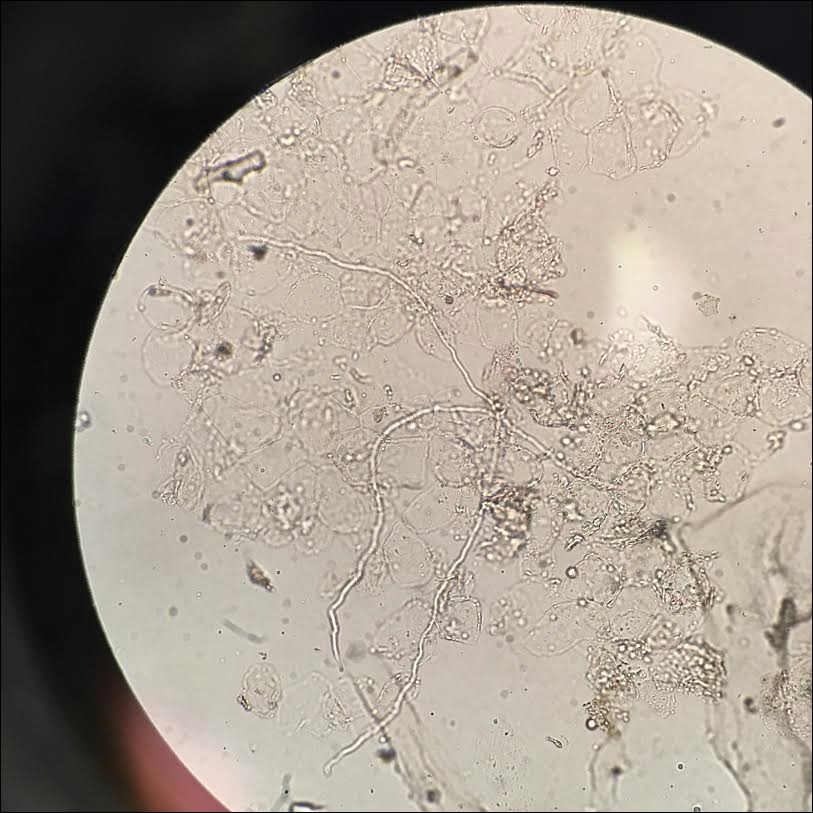

Given the morphology of the plaque, a potassium hydroxide preparation was performed and was positive for hyphal elements consistent with dermatophyte infection (Figure).

Tinea faciei is a fungal infection of the face caused by a dermatophyte that invades the stratum corneum.1 It is transmitted through direct contact with an infected individual or fomite.2 Infections typically are characterized by annular or serpiginous erythematous plaques with a scaly appearance and advancing edge. There may be associated vesicles, papules, or pustules with crusting around the advancing border.3 Tinea faciei can occur concomitantly with other dermatophytic infections and frequently presents atypically due to different characteristics of facial anatomy when compared to other tinea infections. As a result, it often is misdiagnosed.1

Tinea faciei represents roughly 19% of all superficial fungal infections and occurs more commonly in temperate humid regions.4 It can occur at any age but has bimodal peaks in incidence during childhood and early adulthood.5 The most common causative dermatophytes are Trichophyton tonsurans, Microsporum canis, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Trichophyton rubrum.1 Transmission is mainly through direct contact with infected individuals, animals, or soil, which likely occurred during the close quarters and exercises our patient experienced during basic training in the military.

Tinea faciei often is misdiagnosed and treated with topical corticosteroids. The steroids can give a false impression that the rash is resolving by initially decreasing the inflammatory component and reducing scale, which is referred to as tinea incognito. Once the steroid is stopped, however, the fungal infection often returns worse than the original presentation. The differential diagnosis includes subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, periorificial dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, rosacea, erythema annulare centrifugum, granuloma annulare, sarcoidosis, and contact dermatitis.1,3,6

Diagnosis of tinea faciei is best made with skin scraping of the active border of the lesion. The scraping is treated with potassium hydroxide 10%. Visualizing branching or curving hyphae confirms the diagnosis. Fungal speciation often is not performed due to the long time needed to culture. Wood lamp may fluoresce blue-green if tinea faciei is caused by Microsporum species; however, diagnosis in this manner is limited because other common species do not fluoresce.7

Options for treatment of tinea faciei include topical antifungals for 2 to 6 weeks for localized disease or oral antifungals for more extensive or unresponsive infections for 1 to 8 weeks depending on the agent that is used. If fungal folliculitis is present, oral medication should be given.1 Our patient was treated with oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily for 4 weeks with follow-up after that time to ensure resolution.

- Lin RL, Szepietowski JC, Schwartz RA. Tinea faciei, an often deceptive facial eruption. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:437-440.

- Raimer SS, Beightler EL, Hebert AA, et al. Tinea faciei in infants caused by Trichophyton tonsurans. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:452-454.

- Shapiro L, Cohen HJ. Tinea faciei simulating other dermatoses. JAMA. 1971;215:2106-2107.

- Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses. 2008;51(suppl 4):2-15.

- Jorquera E, Moreno JC, Camacho F. Tinea faciei: epidemiology. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1991;119:101-104.

- Hsu S, Le EH, Khoshevis MR. Differential diagnosis of annular lesions. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:289-296.

- Ponka D, Baddar F. Wood lamp examination. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:976.

The Diagnosis: Tinea Faciei

Given the morphology of the plaque, a potassium hydroxide preparation was performed and was positive for hyphal elements consistent with dermatophyte infection (Figure).

Tinea faciei is a fungal infection of the face caused by a dermatophyte that invades the stratum corneum.1 It is transmitted through direct contact with an infected individual or fomite.2 Infections typically are characterized by annular or serpiginous erythematous plaques with a scaly appearance and advancing edge. There may be associated vesicles, papules, or pustules with crusting around the advancing border.3 Tinea faciei can occur concomitantly with other dermatophytic infections and frequently presents atypically due to different characteristics of facial anatomy when compared to other tinea infections. As a result, it often is misdiagnosed.1

Tinea faciei represents roughly 19% of all superficial fungal infections and occurs more commonly in temperate humid regions.4 It can occur at any age but has bimodal peaks in incidence during childhood and early adulthood.5 The most common causative dermatophytes are Trichophyton tonsurans, Microsporum canis, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Trichophyton rubrum.1 Transmission is mainly through direct contact with infected individuals, animals, or soil, which likely occurred during the close quarters and exercises our patient experienced during basic training in the military.

Tinea faciei often is misdiagnosed and treated with topical corticosteroids. The steroids can give a false impression that the rash is resolving by initially decreasing the inflammatory component and reducing scale, which is referred to as tinea incognito. Once the steroid is stopped, however, the fungal infection often returns worse than the original presentation. The differential diagnosis includes subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, periorificial dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, rosacea, erythema annulare centrifugum, granuloma annulare, sarcoidosis, and contact dermatitis.1,3,6

Diagnosis of tinea faciei is best made with skin scraping of the active border of the lesion. The scraping is treated with potassium hydroxide 10%. Visualizing branching or curving hyphae confirms the diagnosis. Fungal speciation often is not performed due to the long time needed to culture. Wood lamp may fluoresce blue-green if tinea faciei is caused by Microsporum species; however, diagnosis in this manner is limited because other common species do not fluoresce.7

Options for treatment of tinea faciei include topical antifungals for 2 to 6 weeks for localized disease or oral antifungals for more extensive or unresponsive infections for 1 to 8 weeks depending on the agent that is used. If fungal folliculitis is present, oral medication should be given.1 Our patient was treated with oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily for 4 weeks with follow-up after that time to ensure resolution.

The Diagnosis: Tinea Faciei

Given the morphology of the plaque, a potassium hydroxide preparation was performed and was positive for hyphal elements consistent with dermatophyte infection (Figure).

Tinea faciei is a fungal infection of the face caused by a dermatophyte that invades the stratum corneum.1 It is transmitted through direct contact with an infected individual or fomite.2 Infections typically are characterized by annular or serpiginous erythematous plaques with a scaly appearance and advancing edge. There may be associated vesicles, papules, or pustules with crusting around the advancing border.3 Tinea faciei can occur concomitantly with other dermatophytic infections and frequently presents atypically due to different characteristics of facial anatomy when compared to other tinea infections. As a result, it often is misdiagnosed.1

Tinea faciei represents roughly 19% of all superficial fungal infections and occurs more commonly in temperate humid regions.4 It can occur at any age but has bimodal peaks in incidence during childhood and early adulthood.5 The most common causative dermatophytes are Trichophyton tonsurans, Microsporum canis, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, and Trichophyton rubrum.1 Transmission is mainly through direct contact with infected individuals, animals, or soil, which likely occurred during the close quarters and exercises our patient experienced during basic training in the military.

Tinea faciei often is misdiagnosed and treated with topical corticosteroids. The steroids can give a false impression that the rash is resolving by initially decreasing the inflammatory component and reducing scale, which is referred to as tinea incognito. Once the steroid is stopped, however, the fungal infection often returns worse than the original presentation. The differential diagnosis includes subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, periorificial dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, rosacea, erythema annulare centrifugum, granuloma annulare, sarcoidosis, and contact dermatitis.1,3,6

Diagnosis of tinea faciei is best made with skin scraping of the active border of the lesion. The scraping is treated with potassium hydroxide 10%. Visualizing branching or curving hyphae confirms the diagnosis. Fungal speciation often is not performed due to the long time needed to culture. Wood lamp may fluoresce blue-green if tinea faciei is caused by Microsporum species; however, diagnosis in this manner is limited because other common species do not fluoresce.7

Options for treatment of tinea faciei include topical antifungals for 2 to 6 weeks for localized disease or oral antifungals for more extensive or unresponsive infections for 1 to 8 weeks depending on the agent that is used. If fungal folliculitis is present, oral medication should be given.1 Our patient was treated with oral terbinafine 250 mg once daily for 4 weeks with follow-up after that time to ensure resolution.

- Lin RL, Szepietowski JC, Schwartz RA. Tinea faciei, an often deceptive facial eruption. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:437-440.

- Raimer SS, Beightler EL, Hebert AA, et al. Tinea faciei in infants caused by Trichophyton tonsurans. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:452-454.

- Shapiro L, Cohen HJ. Tinea faciei simulating other dermatoses. JAMA. 1971;215:2106-2107.

- Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses. 2008;51(suppl 4):2-15.

- Jorquera E, Moreno JC, Camacho F. Tinea faciei: epidemiology. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1991;119:101-104.

- Hsu S, Le EH, Khoshevis MR. Differential diagnosis of annular lesions. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:289-296.

- Ponka D, Baddar F. Wood lamp examination. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:976.

- Lin RL, Szepietowski JC, Schwartz RA. Tinea faciei, an often deceptive facial eruption. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:437-440.

- Raimer SS, Beightler EL, Hebert AA, et al. Tinea faciei in infants caused by Trichophyton tonsurans. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:452-454.

- Shapiro L, Cohen HJ. Tinea faciei simulating other dermatoses. JAMA. 1971;215:2106-2107.

- Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses. 2008;51(suppl 4):2-15.

- Jorquera E, Moreno JC, Camacho F. Tinea faciei: epidemiology. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1991;119:101-104.

- Hsu S, Le EH, Khoshevis MR. Differential diagnosis of annular lesions. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:289-296.

- Ponka D, Baddar F. Wood lamp examination. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:976.

A 19-year-old man with a medical history of keloids presented with a slowly enlarging, red, itchy plaque on the left cheek of 1 year's duration that first began to develop during basic training in the military. The patient denied other pain, pruritus, or separate dermatitis. He initially was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1%, which he used for 8 days prior to referral to the dermatology department. The patient denied other acute concerns. On physical examination, multiple erythematous papules coalescing into a large, 10-cm, papulosquamous, arciform plaque were noted on the left preauricular cheek.