User login

Where to find guidance on using pharmacogenomics in psychiatric practice

Pharmacogenomics—the study of how genetic variability influences drug response—is increasingly being used to personalize pharmacotherapy. Used in the context of other clinical variables, genetic-based drug selection and dosing could help clinicians choose the right therapy for a patient, thus minimizing the incidence of treatment failure and intolerable side effects. Pharmacogenomics could be particularly useful in psychiatric pharmacotherapy, where response rates are low and the risk of adverse effects and nonadherence is high.

Despite the potential benefits of pharmacogenetic testing, many barriers prevent its routine use in practice, including a lack of knowledge about how to (1) order gene tests, (2) interpret results for an individual patient, and (3) apply those results to care. To help bridge this knowledge gap, we list practical, freely available pharmacogenomics resources that a psychiatric practitioner can use.

CPIC guidelines

The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) is an international collaboration of pharmacogenomics experts that publishes clinical practice guidelines on using pharmacogenetic test results to optimize drug therapy.1 Note: These guidelines do not address when tests should be ordered, but rather how results should be used to guide prescribing.

- how to convert genotype to phenotype

- how to modify drug selection or dosing based on these results

- the level of evidence for each recommendation.

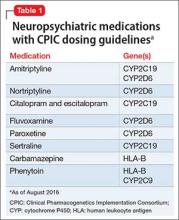

CPIC guidelines and supplementary information are available on the CPIC Web site (https://www.cpicpgx.org) and are updated regularly. Table 1 provides current CPIC guidelines for neuropsychiatric drugs.

PharmGKB

Providing searchable annotations of pharmacogenetic variants, PharmGKB summarizes the clinical implications of important pharmacogenes, and includes FDA drug labels containing pharmacogenomics information (https://www.pharmgkb.org).2 The Web site also provides users with evidence-based figures illustrating the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic pathways of drugs that have pharmacogenetic implications.

PharmGKB is an excellent resource to consult for a summary of available evidence when a CPIC guideline does not exist for a given gene or drug.

Other resources

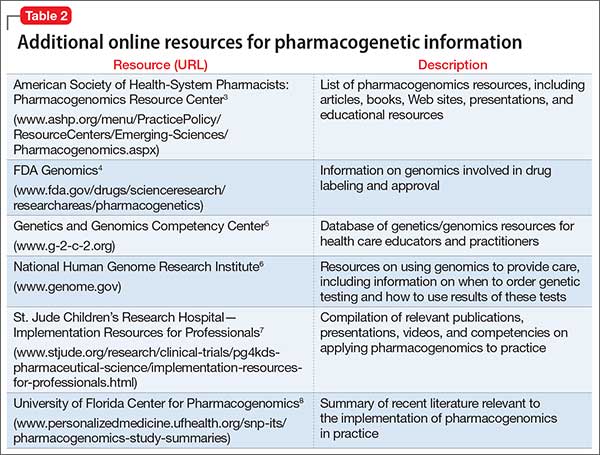

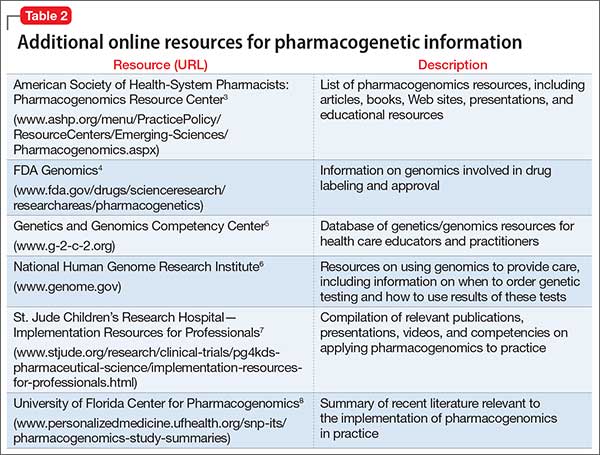

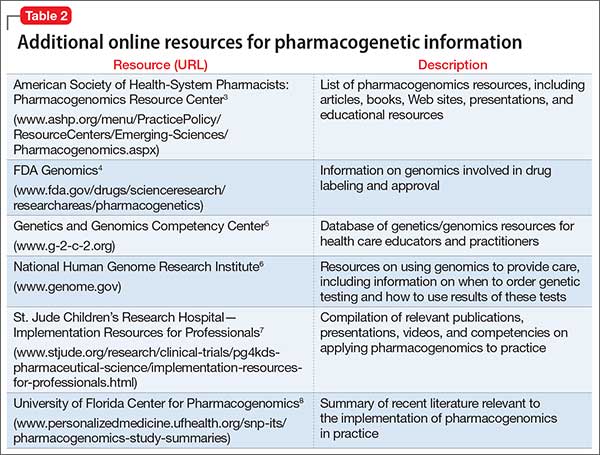

Table 23-8 lists other online resources for practitioners to aid in advancing pharmacogenomics knowledge as it relates to practice.

Putting guidance to best use

Familiarity with resources such as CPIC guidelines and PharmGKB can help ensure that patients with pharmacogenetic test results receive genetically tailored therapy that is more likely to be effective and less likely to cause adverse effects.9,10

1. Caudle KE, Klein TE, Hoffman JM, et al. Incorporation of pharmacogenomics into routine clinical practice: the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline development process. Curr Drug Metab. 2014;15(2):209-217.

2. Thorn CF, Klein TE, Altman RB. PharmGKB: the Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1015:311-320.

3. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Pharmacogenomics resource center. http://www.ashp.org/menu/PracticePolicy/ResourceCenters/Emerging-Sciences/Pharmacogenomics.aspx. Accessed July 21, 2016.

4. Genomics. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda.gov/drugs/scienceresearch/researchareas/pharmacogenetics. Updated May 5, 2016. Accessed July 27, 2016.

5. National Human Genome Research Institute. Genetics/genomics competency center. http://g-2-c-2.org. Accessed July 21, 2016.

6. National Human Genome Research Institute. https://www.genome.gov. Accessed July 21, 2016.

7. Implementation resources for professionals. St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. https://www.stjude.org/research/clinical-trials/pg4kds-pharmaceutical-science/implementation-resources-for-professionals.html. Accessed July 21, 2016.

8. SNPits study summaries. University of Florida Health Personalized Medicine Program. http://personalizedmedicine.ufhealth.org/snp-its/pharmacogenomics-study-summaries. Updated June 1, 2016. Accessed July 21, 2016.

9. Zhang G, Zhang Y, Ling Y. Web resources for pharmacogenomics. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2015;13(1):51-54.

10. Johnson G. Leading clinical pharmacogenomics implementation: advancing pharmacy practice. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(15):1324-1328.

Pharmacogenomics—the study of how genetic variability influences drug response—is increasingly being used to personalize pharmacotherapy. Used in the context of other clinical variables, genetic-based drug selection and dosing could help clinicians choose the right therapy for a patient, thus minimizing the incidence of treatment failure and intolerable side effects. Pharmacogenomics could be particularly useful in psychiatric pharmacotherapy, where response rates are low and the risk of adverse effects and nonadherence is high.

Despite the potential benefits of pharmacogenetic testing, many barriers prevent its routine use in practice, including a lack of knowledge about how to (1) order gene tests, (2) interpret results for an individual patient, and (3) apply those results to care. To help bridge this knowledge gap, we list practical, freely available pharmacogenomics resources that a psychiatric practitioner can use.

CPIC guidelines

The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) is an international collaboration of pharmacogenomics experts that publishes clinical practice guidelines on using pharmacogenetic test results to optimize drug therapy.1 Note: These guidelines do not address when tests should be ordered, but rather how results should be used to guide prescribing.

- how to convert genotype to phenotype

- how to modify drug selection or dosing based on these results

- the level of evidence for each recommendation.

CPIC guidelines and supplementary information are available on the CPIC Web site (https://www.cpicpgx.org) and are updated regularly. Table 1 provides current CPIC guidelines for neuropsychiatric drugs.

PharmGKB

Providing searchable annotations of pharmacogenetic variants, PharmGKB summarizes the clinical implications of important pharmacogenes, and includes FDA drug labels containing pharmacogenomics information (https://www.pharmgkb.org).2 The Web site also provides users with evidence-based figures illustrating the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic pathways of drugs that have pharmacogenetic implications.

PharmGKB is an excellent resource to consult for a summary of available evidence when a CPIC guideline does not exist for a given gene or drug.

Other resources

Table 23-8 lists other online resources for practitioners to aid in advancing pharmacogenomics knowledge as it relates to practice.

Putting guidance to best use

Familiarity with resources such as CPIC guidelines and PharmGKB can help ensure that patients with pharmacogenetic test results receive genetically tailored therapy that is more likely to be effective and less likely to cause adverse effects.9,10

Pharmacogenomics—the study of how genetic variability influences drug response—is increasingly being used to personalize pharmacotherapy. Used in the context of other clinical variables, genetic-based drug selection and dosing could help clinicians choose the right therapy for a patient, thus minimizing the incidence of treatment failure and intolerable side effects. Pharmacogenomics could be particularly useful in psychiatric pharmacotherapy, where response rates are low and the risk of adverse effects and nonadherence is high.

Despite the potential benefits of pharmacogenetic testing, many barriers prevent its routine use in practice, including a lack of knowledge about how to (1) order gene tests, (2) interpret results for an individual patient, and (3) apply those results to care. To help bridge this knowledge gap, we list practical, freely available pharmacogenomics resources that a psychiatric practitioner can use.

CPIC guidelines

The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) is an international collaboration of pharmacogenomics experts that publishes clinical practice guidelines on using pharmacogenetic test results to optimize drug therapy.1 Note: These guidelines do not address when tests should be ordered, but rather how results should be used to guide prescribing.

- how to convert genotype to phenotype

- how to modify drug selection or dosing based on these results

- the level of evidence for each recommendation.

CPIC guidelines and supplementary information are available on the CPIC Web site (https://www.cpicpgx.org) and are updated regularly. Table 1 provides current CPIC guidelines for neuropsychiatric drugs.

PharmGKB

Providing searchable annotations of pharmacogenetic variants, PharmGKB summarizes the clinical implications of important pharmacogenes, and includes FDA drug labels containing pharmacogenomics information (https://www.pharmgkb.org).2 The Web site also provides users with evidence-based figures illustrating the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic pathways of drugs that have pharmacogenetic implications.

PharmGKB is an excellent resource to consult for a summary of available evidence when a CPIC guideline does not exist for a given gene or drug.

Other resources

Table 23-8 lists other online resources for practitioners to aid in advancing pharmacogenomics knowledge as it relates to practice.

Putting guidance to best use

Familiarity with resources such as CPIC guidelines and PharmGKB can help ensure that patients with pharmacogenetic test results receive genetically tailored therapy that is more likely to be effective and less likely to cause adverse effects.9,10

1. Caudle KE, Klein TE, Hoffman JM, et al. Incorporation of pharmacogenomics into routine clinical practice: the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline development process. Curr Drug Metab. 2014;15(2):209-217.

2. Thorn CF, Klein TE, Altman RB. PharmGKB: the Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1015:311-320.

3. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Pharmacogenomics resource center. http://www.ashp.org/menu/PracticePolicy/ResourceCenters/Emerging-Sciences/Pharmacogenomics.aspx. Accessed July 21, 2016.

4. Genomics. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda.gov/drugs/scienceresearch/researchareas/pharmacogenetics. Updated May 5, 2016. Accessed July 27, 2016.

5. National Human Genome Research Institute. Genetics/genomics competency center. http://g-2-c-2.org. Accessed July 21, 2016.

6. National Human Genome Research Institute. https://www.genome.gov. Accessed July 21, 2016.

7. Implementation resources for professionals. St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. https://www.stjude.org/research/clinical-trials/pg4kds-pharmaceutical-science/implementation-resources-for-professionals.html. Accessed July 21, 2016.

8. SNPits study summaries. University of Florida Health Personalized Medicine Program. http://personalizedmedicine.ufhealth.org/snp-its/pharmacogenomics-study-summaries. Updated June 1, 2016. Accessed July 21, 2016.

9. Zhang G, Zhang Y, Ling Y. Web resources for pharmacogenomics. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2015;13(1):51-54.

10. Johnson G. Leading clinical pharmacogenomics implementation: advancing pharmacy practice. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(15):1324-1328.

1. Caudle KE, Klein TE, Hoffman JM, et al. Incorporation of pharmacogenomics into routine clinical practice: the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline development process. Curr Drug Metab. 2014;15(2):209-217.

2. Thorn CF, Klein TE, Altman RB. PharmGKB: the Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1015:311-320.

3. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Pharmacogenomics resource center. http://www.ashp.org/menu/PracticePolicy/ResourceCenters/Emerging-Sciences/Pharmacogenomics.aspx. Accessed July 21, 2016.

4. Genomics. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda.gov/drugs/scienceresearch/researchareas/pharmacogenetics. Updated May 5, 2016. Accessed July 27, 2016.

5. National Human Genome Research Institute. Genetics/genomics competency center. http://g-2-c-2.org. Accessed July 21, 2016.

6. National Human Genome Research Institute. https://www.genome.gov. Accessed July 21, 2016.

7. Implementation resources for professionals. St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. https://www.stjude.org/research/clinical-trials/pg4kds-pharmaceutical-science/implementation-resources-for-professionals.html. Accessed July 21, 2016.

8. SNPits study summaries. University of Florida Health Personalized Medicine Program. http://personalizedmedicine.ufhealth.org/snp-its/pharmacogenomics-study-summaries. Updated June 1, 2016. Accessed July 21, 2016.

9. Zhang G, Zhang Y, Ling Y. Web resources for pharmacogenomics. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2015;13(1):51-54.

10. Johnson G. Leading clinical pharmacogenomics implementation: advancing pharmacy practice. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(15):1324-1328.