User login

Vacuum-Assisted Closure Therapy

Vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) therapy has been used to manage wounds for 20 years and has taken wound treatment to a higher level. Clinical applications include chronic and acute wounds. Wound treatment has become easier with VAC. It improves the quality of life of the patient and reduces hospitalization time and expenses.

With the development of a portable vacuum device, treating patients with wounds is possible even in the home. We have been treating admitted and home care patients with VAC for five years in our Wound Centre. In this article, we discuss our experiences with VAC and review the procedure’s current applications and complications.

Background

Before the introduction of VAC therapy, the treatment and management of difficult wounds mainly belonged in the arena of plastic and reconstructive surgery.1 When Morykwas and colleagues developed VAC, however, they could have hoped only that it would take the treatment of acute and chronic wounds to a higher level.2 VAC is also known as TNP (topical negative pressure), as SPD (sub-atmospheric pressure), as VST (vacuum sealing technique), and as SSS (sealed surface wound suction).3 It is a technique that is easy to use in a clinical setting, and it has a low complication rate.4 The portable VAC system has made wound treatment possible in a home care setting, a development that improves quality of life and reduces hospitalization time.5,6 The portable VAC system (V.A.C. Freedom) is the size of a regular handbag. (See Figure 1, left.)

In this paper, we will discuss the working mechanisms of VAC, its current clinical applications, and the complications that might occur during VAC treatment.

How Does It Work?

Normally, wounds heal by approximation of the wound edges—for example, by suturing or by the formation of a matrix of small blood vessels and connective tissue, when wound edges are not opposed, for the migration of keratinocytes across the surface and the re-epithelialization of the defect. This is a complex process; its main objectives can be considered minimization of blood loss, replacement of any defects with new tissue (granulation), and the restoration of an intact epithelial barrier. For this process to occur, healing debris must be removed, infection must be controlled, and inflammation must be cleared.4 Further disturbance of the rate of healing may occur due to inadequate vascular supply and incapacity of the wound to form new capillaries or matrix. Any disruption in the processes involved in wound healing, such as debridement, granulation, and epithelialization, can lead to the formation of a chronic wound. In our Wound Centre, VAC is mainly used in the granulation phase of a wound, as well as for securing split skin grafts.7

VAC uses medical-grade, open cell polyurethane ether foam.2,4 The pore size is generally 400-600 micrometers. This foam is cut to fit the wound bed before it is applied to the wound. If necessary, multiple pieces of foam can be used to connect separate wounds or to fill up any remaining gaps. Adhesive tape is then applied over an additional three to five cm border of intact skin to provide a seal.4 Then a track pad is placed over a small hole in the adhesive tape. A tube connects the track pad to an adjustable vacuum pump and a canister for collecting effluent fluids. The pump can be adjusted for both the timing (intermittent vs. continuous) and the magnitude of the vacuum effect.4 In general, an intermittent cycle (five minutes on, two minutes off) is used; this has been shown to be most beneficial.2 The VAC system is easy to apply, even on difficult wounds like the open abdomen. (See Figure 2, left.)

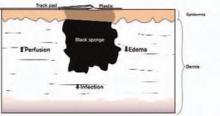

With the VAC technique, the open wound is converted into a controlled and temporarily closed environment. Animal studies have shown that VAC optimizes blood flow, decreases local edema, reduces bacteria levels, and removes excess fluids from the wound.2,8 (See Figure 3, above.) The cyclical application of sub-atmospheric pressure alters the cytoskeleton of the cells in the wound bed, triggering a cascade of intracellular signals that increases the rate of cell division and, thus, the formation of granulation tissue.9 This results in faster healing of the wounds than would have occurred with regular therapy; further, it significantly reduces hospitalization time and expenses.

Indications

VAC can be used on several types of wounds; however, before starting VAC therapy; adequate debridement for the formation of granulation tissue is essential.10 An overview of current clinical applications follows.

Chronic Wounds

The VAC system was originally designed to treat chronic wounds and to simplify the treatment of patients with chronic wounds both inside and outside the hospital.11 Around 10% of the general population will develop a chronic wound in the course of a lifetime; mortality resulting from these wounds amounts to 2.5%.12 VAC therapy has changed the clinical approach to and management of chronic wounds such as venous stasis ulcers, pressure ulcers, surgical dehisced wounds, arterial and diabetic ulcers, and a wide variety of other types of lingering wounds.12-15 Chronic wounds should be adequately debrided, either surgically or using another approach such as maggot debridement.16-18 This converts a chronic wound into a semi-acute wound. Such wounds respond better to VAC therapy than non-debrided wounds.11

Acute Wounds

VAC has become widely accepted in the treatment of large soft-tissue injuries with compromised tissue; it is also used for contaminated wounds, hematomas, and gunshot wounds. It has successfully been used in the treatment of extremities and orthopedic trauma and in treating degloving injuries and burns.19,21-25 (See Figure 4, p. 41.) When using VAC on traumatic injuries, nonviable tissue must be debrided, foreign bodies removed, and hemostasis obtained. Coverage of vital structures such as major vessels, viscera, and nerves by mobilization of local muscle or soft tissue is preferential. Wounds are then treated with VAC, and dressings are changed at appropriate intervals; if there is any suspicion of significant contamination, or if the patient develops signs of infection, adequate action, such as antibiotics or more dressing changes, must be taken.11

VAC therapy can also be used on a wide variety of surgical wounds and in treating surgical complications. It has successfully been used in sternal infections and mediastinitis, abdominal wall defects, enterocutaneous fistula, and perineal surgical wounds.11,26-35 The application of VAC in both chronic and acute wounds shows that it is a technique that facilitates wound management and wound healing for a wide variety of wound types.

Complications

When used within recommendations, complications resulting from VAC are infrequent.4 As the vacuum system device is more frequently adapted to multiple problems, however, the complication rate increases, probably due to co-morbidity and mortality.11 Localized superficial skin irritation is the most common complication reported in the literature.36 Further complications involve pain, infection, bleeding, and fluid depletion.4,12,35-37 Rare, severe complications, such as toxic shock syndrome, anaerobic sepsis, or thrombosis have been described as well.38-39(Also see M. Leijnen, MD, MSc, and colleagues, unpublished data, 2007.)

Conclusion

After 20 years of experience with vacuum-assisted closure, we can state that VAC therapy contributes positively to wound treatment. Wounds treated with this procedure are easier to manage, both in the hospital and at home. It can be used on a wide variety of chronic and acute wounds, and more applications are being developed. The procedure also reduces hospitalization time and expenses, and perhaps most important, it improves the patient’s quality of life. TH

M. Leijnen, MD, MSc, and S.A. da Costa, MD, PhD, practice in the Department of Surgery, Rijnland Hospital, Leiderdorp, The Netherlands. L. van Doorn, MA-NPA, practices in the Rijnland Wound Centre, Leiderdorp, The Netherlands. P. Steenvoorde, MD, MSc, and J. Oskam, MD, PhD practice in the Department of Surgery, Rijnland Hospital, Leiderdorp, The Netherlands, and in the Rijnland Wound Center, Leiderdorp, The Netherlands.

References

- Argenta LC, Morykwas MJ. Vacuum-assisted closure: a new method for wound control and treatment: clinical experience. Ann Plast Surg. 1997 Jun;38(6):563-576; discussion 577. Ann Plast Surg. 2000 Sep;45(3):332-334; discussion 335-336.

- Morykwas MJ, Argenta LC, Shelton-Brown EI, et al. Vacuum assisted closure: a new method for wound control and treatment: animal studies and basic foundation. Ann Plast Surg. 1997 Jun;38(6):553-562. Comment in: Ann Plast Surg. 2000 Sep;45(3):332-334; discussion 335-336.

- Banwell PE, Teot L. Topical negative pressure (TNP): the evolution of a novel wound therapy. J Wound Care. 2003;12(1):22-28. Review.

- Lambert KV, Hayes P, McCarthy M. Vacuum assisted closure: a review of development and current applications. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005 Mar;29(3):219-226.

- Baradarian S, Stahovich M, Krause S, et al. Case series: clinical management of persistent mechanical assist device driveline drainage using vacuum-assisted closure therapy. ASAIO J. 2006;52:354-356.

- Sposato G, Molea G, Di Caprio G, et al. Ambulant vacuum-assisted closure of skin-graft dressing in the lower limbs using a portable mini-VAC device. Br J Plast Surg. 2001 Apr;54(3):235-237.

- Scherer LA, Shiver S, Chang M, et al. The vacuum assisted closure device: a method of securing skin grafts and improving graft survival. Arch Surg. 2002 Aug;137(8):930-933.

- Chen SZ, Li J, Li XY, et al. Effects of vacuum-assisted closure on wound microcirculation: an experimental study. Asian J Surg. 2005 Jul;28(3):211-217.

- Venturi ML, Attinger CE, Mesbahi AN, et al. Mechanisms and clinical applications of the vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) device: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6(3):185-194. Review.

- Philbeck TE Jr, Whittington KT, Millsap MH, et al. The clinical and cost effectiveness of externally applied negative pressure wound therapy in the treatment of wounds in home healthcare Medicare patients. Ostomy Wound Manage. 1999 Nov;45(11):41-50.

- Argenta LC, Morykwas MJ, Marks MW, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure: state of clinic art. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006 Jun;117(7 Suppl):127S-142S.

- Karl T, Modic PK, Voss EU. Indications and results of VAC therapy treatments in vascular surgery - state of the art in the treatment of chronic wounds [in German]. Zentralbl Chir. 2004 May;129 Suppl 1:S74-S79.

- Ford CN, Reinhard ER, Yeh D, et al. Interim analysis of a prospective, randomized trial of vacuum-assisted closure versus the healthpoint system in the management of pressure ulcers. Ann Plast Surg. 2002 Jul;49(1):55-61.

- Joseph E, Hamori CA, Bergman S, et al. A prospective randomized trial of vacuum-assisted closure versus standard therapy of chronic non-healing wounds. Wounds. 2000;12:60-67.

- Rozeboom AL, Steenvoorde P, Hartgrink HH, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis of the leg following a simple pelvic fracture: case report and literature review. J Wound Care. 2006;15:117-120.

- Steenvoorde P, Calame JJ, Oskam J. Maggot-treated wounds follow normal wound healing phases. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1477-1479.

- Mumcuoglu KY. Clinical applications for maggots in wound care. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2(4):219-227.

- Attinger CE, Bulan EJ. Debridement. The key initial first step in wound healing. Foot Ankle Clin. 2001 Dec;6(4):627-660.

- Stannard JP, Robinson JT, Anderson ER, et al. Negative pressure wound therapy to treat hematomas and surgical incisions following high-energy trauma. J Trauma. 2006 Jun;60(6):1301-1306.

- Webb LX, Laver D, DeFranzo A. Negative pressure wound therapy in the management of orthopedic wounds. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2004 Apr;50(4A Suppl):26-27.

- Herscovici D Jr, Sanders RW, Scaduto JM, et al. Vacuum-assisted wound closure (VAC therapy) for the management of patients with high-energy soft tissue injuries. J Orthop Trauma. 2003 Nov-Dec;17(10):683-688.

- Wong LK, Nesbit RD, Turner LA, et al. Management of a circumferential lower extremity degloving injury with the use of vacuum-assisted closure. South Med J. 2006;99:628-630.

- Josty IC, Ramaswamy R, Laing JH. Vacuum assisted closure: an alternative strategy in the management of degloving injuries of the foot. Br J Plast Surg. 2001 Jun;54(4):363-365.

- Adamkova M, Tymonova J, Zamecnikova I, et al. First experience with the use of vacuum assisted closure in the treatment of skin defects at the burn center. Acta Chir Plast. 2005;47(1):24-27.

- Kamolz LP, Andel H, Haslik W, et al. Use of subatmospheric pressure therapy to prevent burn wound progression in human: first experiences. Burns. 2004;30:253-258.

- Obdeijn MC, de Lange MY, Lichtendahl DH, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure in the treatment of poststernotomy mediastinitis. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:2358-2360.

- Agarwal JP, Ogilvie M, Wu LC, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure for sternal wounds: a first-line therapeutic management approach. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1035-1040.

- Scholl L, Chang E, Reitz B, et al. Sternal osteomyelitis: use of vacuum-assisted closure device as an adjunct to definitive closure with sternectomy and muscle flap reconstruction. J Card Surg. 2004 Sep-Oct;19(5):453-461.

- DeFranzo AJ, Argenta L. Vacuum-assisted closure for the treatment of abdominal wounds. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33:213-224.

- Nienhuijs SW, Manupassa R, Strobbe LJ, et al. Can topical negative pressure be used to control complex enterocutaneous fistulae? J Wound Care. 2003;12:343-345.

- Alvarez AA, Maxwell GL, Rodriguez GC. Vacuum-assisted closure for cutaneous gastrointestinal fistula management. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;80:413-416.

- Erdmann D, Drye C, Heller L, et al. Abdominal wall defect and enterocutaneous fistula treatment with the Vacuum-Assisted Closure (V.A.C.) system. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:2066-2068.

- Schaffzin DM, Douglas JM, Stahl TJ, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure of complex perineal wounds. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1745-1748.

- Jethwa P, Lake SP. Using topical negative pressure therapy to resolve wound failure following perineal resection. J Wound Care. 2005;14:166-167.

- McGuinness JG, Winter DC, O’Connell PR. Vacuum-assisted closure of a complex pilonidal sinus. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:274-276.

- Steenvoorde P, van Engeland A. Oskam J. Vacuum-assisted closure therapy and oral anticoagulation therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:2220-2221.

- Negative pressure wound therapy: Morykwas approach [adverse events data]. Available at: www.npwt.com/morykwas.htm. Last accessed March 20, 2007.

- Carson SN, Overall K, Lee-Jahshan S, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure used for healing chronic wounds and skin grafts in the lower extremities. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2004;50:52-58.

- Gwan-Nulla D, Casal RS. Toxic shock syndrome associated with the use of the vacuum-assisted closure device. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;47:552-554.

Vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) therapy has been used to manage wounds for 20 years and has taken wound treatment to a higher level. Clinical applications include chronic and acute wounds. Wound treatment has become easier with VAC. It improves the quality of life of the patient and reduces hospitalization time and expenses.

With the development of a portable vacuum device, treating patients with wounds is possible even in the home. We have been treating admitted and home care patients with VAC for five years in our Wound Centre. In this article, we discuss our experiences with VAC and review the procedure’s current applications and complications.

Background

Before the introduction of VAC therapy, the treatment and management of difficult wounds mainly belonged in the arena of plastic and reconstructive surgery.1 When Morykwas and colleagues developed VAC, however, they could have hoped only that it would take the treatment of acute and chronic wounds to a higher level.2 VAC is also known as TNP (topical negative pressure), as SPD (sub-atmospheric pressure), as VST (vacuum sealing technique), and as SSS (sealed surface wound suction).3 It is a technique that is easy to use in a clinical setting, and it has a low complication rate.4 The portable VAC system has made wound treatment possible in a home care setting, a development that improves quality of life and reduces hospitalization time.5,6 The portable VAC system (V.A.C. Freedom) is the size of a regular handbag. (See Figure 1, left.)

In this paper, we will discuss the working mechanisms of VAC, its current clinical applications, and the complications that might occur during VAC treatment.

How Does It Work?

Normally, wounds heal by approximation of the wound edges—for example, by suturing or by the formation of a matrix of small blood vessels and connective tissue, when wound edges are not opposed, for the migration of keratinocytes across the surface and the re-epithelialization of the defect. This is a complex process; its main objectives can be considered minimization of blood loss, replacement of any defects with new tissue (granulation), and the restoration of an intact epithelial barrier. For this process to occur, healing debris must be removed, infection must be controlled, and inflammation must be cleared.4 Further disturbance of the rate of healing may occur due to inadequate vascular supply and incapacity of the wound to form new capillaries or matrix. Any disruption in the processes involved in wound healing, such as debridement, granulation, and epithelialization, can lead to the formation of a chronic wound. In our Wound Centre, VAC is mainly used in the granulation phase of a wound, as well as for securing split skin grafts.7

VAC uses medical-grade, open cell polyurethane ether foam.2,4 The pore size is generally 400-600 micrometers. This foam is cut to fit the wound bed before it is applied to the wound. If necessary, multiple pieces of foam can be used to connect separate wounds or to fill up any remaining gaps. Adhesive tape is then applied over an additional three to five cm border of intact skin to provide a seal.4 Then a track pad is placed over a small hole in the adhesive tape. A tube connects the track pad to an adjustable vacuum pump and a canister for collecting effluent fluids. The pump can be adjusted for both the timing (intermittent vs. continuous) and the magnitude of the vacuum effect.4 In general, an intermittent cycle (five minutes on, two minutes off) is used; this has been shown to be most beneficial.2 The VAC system is easy to apply, even on difficult wounds like the open abdomen. (See Figure 2, left.)

With the VAC technique, the open wound is converted into a controlled and temporarily closed environment. Animal studies have shown that VAC optimizes blood flow, decreases local edema, reduces bacteria levels, and removes excess fluids from the wound.2,8 (See Figure 3, above.) The cyclical application of sub-atmospheric pressure alters the cytoskeleton of the cells in the wound bed, triggering a cascade of intracellular signals that increases the rate of cell division and, thus, the formation of granulation tissue.9 This results in faster healing of the wounds than would have occurred with regular therapy; further, it significantly reduces hospitalization time and expenses.

Indications

VAC can be used on several types of wounds; however, before starting VAC therapy; adequate debridement for the formation of granulation tissue is essential.10 An overview of current clinical applications follows.

Chronic Wounds

The VAC system was originally designed to treat chronic wounds and to simplify the treatment of patients with chronic wounds both inside and outside the hospital.11 Around 10% of the general population will develop a chronic wound in the course of a lifetime; mortality resulting from these wounds amounts to 2.5%.12 VAC therapy has changed the clinical approach to and management of chronic wounds such as venous stasis ulcers, pressure ulcers, surgical dehisced wounds, arterial and diabetic ulcers, and a wide variety of other types of lingering wounds.12-15 Chronic wounds should be adequately debrided, either surgically or using another approach such as maggot debridement.16-18 This converts a chronic wound into a semi-acute wound. Such wounds respond better to VAC therapy than non-debrided wounds.11

Acute Wounds

VAC has become widely accepted in the treatment of large soft-tissue injuries with compromised tissue; it is also used for contaminated wounds, hematomas, and gunshot wounds. It has successfully been used in the treatment of extremities and orthopedic trauma and in treating degloving injuries and burns.19,21-25 (See Figure 4, p. 41.) When using VAC on traumatic injuries, nonviable tissue must be debrided, foreign bodies removed, and hemostasis obtained. Coverage of vital structures such as major vessels, viscera, and nerves by mobilization of local muscle or soft tissue is preferential. Wounds are then treated with VAC, and dressings are changed at appropriate intervals; if there is any suspicion of significant contamination, or if the patient develops signs of infection, adequate action, such as antibiotics or more dressing changes, must be taken.11

VAC therapy can also be used on a wide variety of surgical wounds and in treating surgical complications. It has successfully been used in sternal infections and mediastinitis, abdominal wall defects, enterocutaneous fistula, and perineal surgical wounds.11,26-35 The application of VAC in both chronic and acute wounds shows that it is a technique that facilitates wound management and wound healing for a wide variety of wound types.

Complications

When used within recommendations, complications resulting from VAC are infrequent.4 As the vacuum system device is more frequently adapted to multiple problems, however, the complication rate increases, probably due to co-morbidity and mortality.11 Localized superficial skin irritation is the most common complication reported in the literature.36 Further complications involve pain, infection, bleeding, and fluid depletion.4,12,35-37 Rare, severe complications, such as toxic shock syndrome, anaerobic sepsis, or thrombosis have been described as well.38-39(Also see M. Leijnen, MD, MSc, and colleagues, unpublished data, 2007.)

Conclusion

After 20 years of experience with vacuum-assisted closure, we can state that VAC therapy contributes positively to wound treatment. Wounds treated with this procedure are easier to manage, both in the hospital and at home. It can be used on a wide variety of chronic and acute wounds, and more applications are being developed. The procedure also reduces hospitalization time and expenses, and perhaps most important, it improves the patient’s quality of life. TH

M. Leijnen, MD, MSc, and S.A. da Costa, MD, PhD, practice in the Department of Surgery, Rijnland Hospital, Leiderdorp, The Netherlands. L. van Doorn, MA-NPA, practices in the Rijnland Wound Centre, Leiderdorp, The Netherlands. P. Steenvoorde, MD, MSc, and J. Oskam, MD, PhD practice in the Department of Surgery, Rijnland Hospital, Leiderdorp, The Netherlands, and in the Rijnland Wound Center, Leiderdorp, The Netherlands.

References

- Argenta LC, Morykwas MJ. Vacuum-assisted closure: a new method for wound control and treatment: clinical experience. Ann Plast Surg. 1997 Jun;38(6):563-576; discussion 577. Ann Plast Surg. 2000 Sep;45(3):332-334; discussion 335-336.

- Morykwas MJ, Argenta LC, Shelton-Brown EI, et al. Vacuum assisted closure: a new method for wound control and treatment: animal studies and basic foundation. Ann Plast Surg. 1997 Jun;38(6):553-562. Comment in: Ann Plast Surg. 2000 Sep;45(3):332-334; discussion 335-336.

- Banwell PE, Teot L. Topical negative pressure (TNP): the evolution of a novel wound therapy. J Wound Care. 2003;12(1):22-28. Review.

- Lambert KV, Hayes P, McCarthy M. Vacuum assisted closure: a review of development and current applications. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005 Mar;29(3):219-226.

- Baradarian S, Stahovich M, Krause S, et al. Case series: clinical management of persistent mechanical assist device driveline drainage using vacuum-assisted closure therapy. ASAIO J. 2006;52:354-356.

- Sposato G, Molea G, Di Caprio G, et al. Ambulant vacuum-assisted closure of skin-graft dressing in the lower limbs using a portable mini-VAC device. Br J Plast Surg. 2001 Apr;54(3):235-237.

- Scherer LA, Shiver S, Chang M, et al. The vacuum assisted closure device: a method of securing skin grafts and improving graft survival. Arch Surg. 2002 Aug;137(8):930-933.

- Chen SZ, Li J, Li XY, et al. Effects of vacuum-assisted closure on wound microcirculation: an experimental study. Asian J Surg. 2005 Jul;28(3):211-217.

- Venturi ML, Attinger CE, Mesbahi AN, et al. Mechanisms and clinical applications of the vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) device: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6(3):185-194. Review.

- Philbeck TE Jr, Whittington KT, Millsap MH, et al. The clinical and cost effectiveness of externally applied negative pressure wound therapy in the treatment of wounds in home healthcare Medicare patients. Ostomy Wound Manage. 1999 Nov;45(11):41-50.

- Argenta LC, Morykwas MJ, Marks MW, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure: state of clinic art. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006 Jun;117(7 Suppl):127S-142S.

- Karl T, Modic PK, Voss EU. Indications and results of VAC therapy treatments in vascular surgery - state of the art in the treatment of chronic wounds [in German]. Zentralbl Chir. 2004 May;129 Suppl 1:S74-S79.

- Ford CN, Reinhard ER, Yeh D, et al. Interim analysis of a prospective, randomized trial of vacuum-assisted closure versus the healthpoint system in the management of pressure ulcers. Ann Plast Surg. 2002 Jul;49(1):55-61.

- Joseph E, Hamori CA, Bergman S, et al. A prospective randomized trial of vacuum-assisted closure versus standard therapy of chronic non-healing wounds. Wounds. 2000;12:60-67.

- Rozeboom AL, Steenvoorde P, Hartgrink HH, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis of the leg following a simple pelvic fracture: case report and literature review. J Wound Care. 2006;15:117-120.

- Steenvoorde P, Calame JJ, Oskam J. Maggot-treated wounds follow normal wound healing phases. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1477-1479.

- Mumcuoglu KY. Clinical applications for maggots in wound care. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2(4):219-227.

- Attinger CE, Bulan EJ. Debridement. The key initial first step in wound healing. Foot Ankle Clin. 2001 Dec;6(4):627-660.

- Stannard JP, Robinson JT, Anderson ER, et al. Negative pressure wound therapy to treat hematomas and surgical incisions following high-energy trauma. J Trauma. 2006 Jun;60(6):1301-1306.

- Webb LX, Laver D, DeFranzo A. Negative pressure wound therapy in the management of orthopedic wounds. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2004 Apr;50(4A Suppl):26-27.

- Herscovici D Jr, Sanders RW, Scaduto JM, et al. Vacuum-assisted wound closure (VAC therapy) for the management of patients with high-energy soft tissue injuries. J Orthop Trauma. 2003 Nov-Dec;17(10):683-688.

- Wong LK, Nesbit RD, Turner LA, et al. Management of a circumferential lower extremity degloving injury with the use of vacuum-assisted closure. South Med J. 2006;99:628-630.

- Josty IC, Ramaswamy R, Laing JH. Vacuum assisted closure: an alternative strategy in the management of degloving injuries of the foot. Br J Plast Surg. 2001 Jun;54(4):363-365.

- Adamkova M, Tymonova J, Zamecnikova I, et al. First experience with the use of vacuum assisted closure in the treatment of skin defects at the burn center. Acta Chir Plast. 2005;47(1):24-27.

- Kamolz LP, Andel H, Haslik W, et al. Use of subatmospheric pressure therapy to prevent burn wound progression in human: first experiences. Burns. 2004;30:253-258.

- Obdeijn MC, de Lange MY, Lichtendahl DH, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure in the treatment of poststernotomy mediastinitis. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:2358-2360.

- Agarwal JP, Ogilvie M, Wu LC, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure for sternal wounds: a first-line therapeutic management approach. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1035-1040.

- Scholl L, Chang E, Reitz B, et al. Sternal osteomyelitis: use of vacuum-assisted closure device as an adjunct to definitive closure with sternectomy and muscle flap reconstruction. J Card Surg. 2004 Sep-Oct;19(5):453-461.

- DeFranzo AJ, Argenta L. Vacuum-assisted closure for the treatment of abdominal wounds. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33:213-224.

- Nienhuijs SW, Manupassa R, Strobbe LJ, et al. Can topical negative pressure be used to control complex enterocutaneous fistulae? J Wound Care. 2003;12:343-345.

- Alvarez AA, Maxwell GL, Rodriguez GC. Vacuum-assisted closure for cutaneous gastrointestinal fistula management. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;80:413-416.

- Erdmann D, Drye C, Heller L, et al. Abdominal wall defect and enterocutaneous fistula treatment with the Vacuum-Assisted Closure (V.A.C.) system. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:2066-2068.

- Schaffzin DM, Douglas JM, Stahl TJ, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure of complex perineal wounds. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1745-1748.

- Jethwa P, Lake SP. Using topical negative pressure therapy to resolve wound failure following perineal resection. J Wound Care. 2005;14:166-167.

- McGuinness JG, Winter DC, O’Connell PR. Vacuum-assisted closure of a complex pilonidal sinus. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:274-276.

- Steenvoorde P, van Engeland A. Oskam J. Vacuum-assisted closure therapy and oral anticoagulation therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:2220-2221.

- Negative pressure wound therapy: Morykwas approach [adverse events data]. Available at: www.npwt.com/morykwas.htm. Last accessed March 20, 2007.

- Carson SN, Overall K, Lee-Jahshan S, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure used for healing chronic wounds and skin grafts in the lower extremities. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2004;50:52-58.

- Gwan-Nulla D, Casal RS. Toxic shock syndrome associated with the use of the vacuum-assisted closure device. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;47:552-554.

Vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) therapy has been used to manage wounds for 20 years and has taken wound treatment to a higher level. Clinical applications include chronic and acute wounds. Wound treatment has become easier with VAC. It improves the quality of life of the patient and reduces hospitalization time and expenses.

With the development of a portable vacuum device, treating patients with wounds is possible even in the home. We have been treating admitted and home care patients with VAC for five years in our Wound Centre. In this article, we discuss our experiences with VAC and review the procedure’s current applications and complications.

Background

Before the introduction of VAC therapy, the treatment and management of difficult wounds mainly belonged in the arena of plastic and reconstructive surgery.1 When Morykwas and colleagues developed VAC, however, they could have hoped only that it would take the treatment of acute and chronic wounds to a higher level.2 VAC is also known as TNP (topical negative pressure), as SPD (sub-atmospheric pressure), as VST (vacuum sealing technique), and as SSS (sealed surface wound suction).3 It is a technique that is easy to use in a clinical setting, and it has a low complication rate.4 The portable VAC system has made wound treatment possible in a home care setting, a development that improves quality of life and reduces hospitalization time.5,6 The portable VAC system (V.A.C. Freedom) is the size of a regular handbag. (See Figure 1, left.)

In this paper, we will discuss the working mechanisms of VAC, its current clinical applications, and the complications that might occur during VAC treatment.

How Does It Work?

Normally, wounds heal by approximation of the wound edges—for example, by suturing or by the formation of a matrix of small blood vessels and connective tissue, when wound edges are not opposed, for the migration of keratinocytes across the surface and the re-epithelialization of the defect. This is a complex process; its main objectives can be considered minimization of blood loss, replacement of any defects with new tissue (granulation), and the restoration of an intact epithelial barrier. For this process to occur, healing debris must be removed, infection must be controlled, and inflammation must be cleared.4 Further disturbance of the rate of healing may occur due to inadequate vascular supply and incapacity of the wound to form new capillaries or matrix. Any disruption in the processes involved in wound healing, such as debridement, granulation, and epithelialization, can lead to the formation of a chronic wound. In our Wound Centre, VAC is mainly used in the granulation phase of a wound, as well as for securing split skin grafts.7

VAC uses medical-grade, open cell polyurethane ether foam.2,4 The pore size is generally 400-600 micrometers. This foam is cut to fit the wound bed before it is applied to the wound. If necessary, multiple pieces of foam can be used to connect separate wounds or to fill up any remaining gaps. Adhesive tape is then applied over an additional three to five cm border of intact skin to provide a seal.4 Then a track pad is placed over a small hole in the adhesive tape. A tube connects the track pad to an adjustable vacuum pump and a canister for collecting effluent fluids. The pump can be adjusted for both the timing (intermittent vs. continuous) and the magnitude of the vacuum effect.4 In general, an intermittent cycle (five minutes on, two minutes off) is used; this has been shown to be most beneficial.2 The VAC system is easy to apply, even on difficult wounds like the open abdomen. (See Figure 2, left.)

With the VAC technique, the open wound is converted into a controlled and temporarily closed environment. Animal studies have shown that VAC optimizes blood flow, decreases local edema, reduces bacteria levels, and removes excess fluids from the wound.2,8 (See Figure 3, above.) The cyclical application of sub-atmospheric pressure alters the cytoskeleton of the cells in the wound bed, triggering a cascade of intracellular signals that increases the rate of cell division and, thus, the formation of granulation tissue.9 This results in faster healing of the wounds than would have occurred with regular therapy; further, it significantly reduces hospitalization time and expenses.

Indications

VAC can be used on several types of wounds; however, before starting VAC therapy; adequate debridement for the formation of granulation tissue is essential.10 An overview of current clinical applications follows.

Chronic Wounds

The VAC system was originally designed to treat chronic wounds and to simplify the treatment of patients with chronic wounds both inside and outside the hospital.11 Around 10% of the general population will develop a chronic wound in the course of a lifetime; mortality resulting from these wounds amounts to 2.5%.12 VAC therapy has changed the clinical approach to and management of chronic wounds such as venous stasis ulcers, pressure ulcers, surgical dehisced wounds, arterial and diabetic ulcers, and a wide variety of other types of lingering wounds.12-15 Chronic wounds should be adequately debrided, either surgically or using another approach such as maggot debridement.16-18 This converts a chronic wound into a semi-acute wound. Such wounds respond better to VAC therapy than non-debrided wounds.11

Acute Wounds

VAC has become widely accepted in the treatment of large soft-tissue injuries with compromised tissue; it is also used for contaminated wounds, hematomas, and gunshot wounds. It has successfully been used in the treatment of extremities and orthopedic trauma and in treating degloving injuries and burns.19,21-25 (See Figure 4, p. 41.) When using VAC on traumatic injuries, nonviable tissue must be debrided, foreign bodies removed, and hemostasis obtained. Coverage of vital structures such as major vessels, viscera, and nerves by mobilization of local muscle or soft tissue is preferential. Wounds are then treated with VAC, and dressings are changed at appropriate intervals; if there is any suspicion of significant contamination, or if the patient develops signs of infection, adequate action, such as antibiotics or more dressing changes, must be taken.11

VAC therapy can also be used on a wide variety of surgical wounds and in treating surgical complications. It has successfully been used in sternal infections and mediastinitis, abdominal wall defects, enterocutaneous fistula, and perineal surgical wounds.11,26-35 The application of VAC in both chronic and acute wounds shows that it is a technique that facilitates wound management and wound healing for a wide variety of wound types.

Complications

When used within recommendations, complications resulting from VAC are infrequent.4 As the vacuum system device is more frequently adapted to multiple problems, however, the complication rate increases, probably due to co-morbidity and mortality.11 Localized superficial skin irritation is the most common complication reported in the literature.36 Further complications involve pain, infection, bleeding, and fluid depletion.4,12,35-37 Rare, severe complications, such as toxic shock syndrome, anaerobic sepsis, or thrombosis have been described as well.38-39(Also see M. Leijnen, MD, MSc, and colleagues, unpublished data, 2007.)

Conclusion

After 20 years of experience with vacuum-assisted closure, we can state that VAC therapy contributes positively to wound treatment. Wounds treated with this procedure are easier to manage, both in the hospital and at home. It can be used on a wide variety of chronic and acute wounds, and more applications are being developed. The procedure also reduces hospitalization time and expenses, and perhaps most important, it improves the patient’s quality of life. TH

M. Leijnen, MD, MSc, and S.A. da Costa, MD, PhD, practice in the Department of Surgery, Rijnland Hospital, Leiderdorp, The Netherlands. L. van Doorn, MA-NPA, practices in the Rijnland Wound Centre, Leiderdorp, The Netherlands. P. Steenvoorde, MD, MSc, and J. Oskam, MD, PhD practice in the Department of Surgery, Rijnland Hospital, Leiderdorp, The Netherlands, and in the Rijnland Wound Center, Leiderdorp, The Netherlands.

References

- Argenta LC, Morykwas MJ. Vacuum-assisted closure: a new method for wound control and treatment: clinical experience. Ann Plast Surg. 1997 Jun;38(6):563-576; discussion 577. Ann Plast Surg. 2000 Sep;45(3):332-334; discussion 335-336.

- Morykwas MJ, Argenta LC, Shelton-Brown EI, et al. Vacuum assisted closure: a new method for wound control and treatment: animal studies and basic foundation. Ann Plast Surg. 1997 Jun;38(6):553-562. Comment in: Ann Plast Surg. 2000 Sep;45(3):332-334; discussion 335-336.

- Banwell PE, Teot L. Topical negative pressure (TNP): the evolution of a novel wound therapy. J Wound Care. 2003;12(1):22-28. Review.

- Lambert KV, Hayes P, McCarthy M. Vacuum assisted closure: a review of development and current applications. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005 Mar;29(3):219-226.

- Baradarian S, Stahovich M, Krause S, et al. Case series: clinical management of persistent mechanical assist device driveline drainage using vacuum-assisted closure therapy. ASAIO J. 2006;52:354-356.

- Sposato G, Molea G, Di Caprio G, et al. Ambulant vacuum-assisted closure of skin-graft dressing in the lower limbs using a portable mini-VAC device. Br J Plast Surg. 2001 Apr;54(3):235-237.

- Scherer LA, Shiver S, Chang M, et al. The vacuum assisted closure device: a method of securing skin grafts and improving graft survival. Arch Surg. 2002 Aug;137(8):930-933.

- Chen SZ, Li J, Li XY, et al. Effects of vacuum-assisted closure on wound microcirculation: an experimental study. Asian J Surg. 2005 Jul;28(3):211-217.

- Venturi ML, Attinger CE, Mesbahi AN, et al. Mechanisms and clinical applications of the vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) device: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6(3):185-194. Review.

- Philbeck TE Jr, Whittington KT, Millsap MH, et al. The clinical and cost effectiveness of externally applied negative pressure wound therapy in the treatment of wounds in home healthcare Medicare patients. Ostomy Wound Manage. 1999 Nov;45(11):41-50.

- Argenta LC, Morykwas MJ, Marks MW, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure: state of clinic art. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006 Jun;117(7 Suppl):127S-142S.

- Karl T, Modic PK, Voss EU. Indications and results of VAC therapy treatments in vascular surgery - state of the art in the treatment of chronic wounds [in German]. Zentralbl Chir. 2004 May;129 Suppl 1:S74-S79.

- Ford CN, Reinhard ER, Yeh D, et al. Interim analysis of a prospective, randomized trial of vacuum-assisted closure versus the healthpoint system in the management of pressure ulcers. Ann Plast Surg. 2002 Jul;49(1):55-61.

- Joseph E, Hamori CA, Bergman S, et al. A prospective randomized trial of vacuum-assisted closure versus standard therapy of chronic non-healing wounds. Wounds. 2000;12:60-67.

- Rozeboom AL, Steenvoorde P, Hartgrink HH, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis of the leg following a simple pelvic fracture: case report and literature review. J Wound Care. 2006;15:117-120.

- Steenvoorde P, Calame JJ, Oskam J. Maggot-treated wounds follow normal wound healing phases. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1477-1479.

- Mumcuoglu KY. Clinical applications for maggots in wound care. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2(4):219-227.

- Attinger CE, Bulan EJ. Debridement. The key initial first step in wound healing. Foot Ankle Clin. 2001 Dec;6(4):627-660.

- Stannard JP, Robinson JT, Anderson ER, et al. Negative pressure wound therapy to treat hematomas and surgical incisions following high-energy trauma. J Trauma. 2006 Jun;60(6):1301-1306.

- Webb LX, Laver D, DeFranzo A. Negative pressure wound therapy in the management of orthopedic wounds. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2004 Apr;50(4A Suppl):26-27.

- Herscovici D Jr, Sanders RW, Scaduto JM, et al. Vacuum-assisted wound closure (VAC therapy) for the management of patients with high-energy soft tissue injuries. J Orthop Trauma. 2003 Nov-Dec;17(10):683-688.

- Wong LK, Nesbit RD, Turner LA, et al. Management of a circumferential lower extremity degloving injury with the use of vacuum-assisted closure. South Med J. 2006;99:628-630.

- Josty IC, Ramaswamy R, Laing JH. Vacuum assisted closure: an alternative strategy in the management of degloving injuries of the foot. Br J Plast Surg. 2001 Jun;54(4):363-365.

- Adamkova M, Tymonova J, Zamecnikova I, et al. First experience with the use of vacuum assisted closure in the treatment of skin defects at the burn center. Acta Chir Plast. 2005;47(1):24-27.

- Kamolz LP, Andel H, Haslik W, et al. Use of subatmospheric pressure therapy to prevent burn wound progression in human: first experiences. Burns. 2004;30:253-258.

- Obdeijn MC, de Lange MY, Lichtendahl DH, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure in the treatment of poststernotomy mediastinitis. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:2358-2360.

- Agarwal JP, Ogilvie M, Wu LC, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure for sternal wounds: a first-line therapeutic management approach. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1035-1040.

- Scholl L, Chang E, Reitz B, et al. Sternal osteomyelitis: use of vacuum-assisted closure device as an adjunct to definitive closure with sternectomy and muscle flap reconstruction. J Card Surg. 2004 Sep-Oct;19(5):453-461.

- DeFranzo AJ, Argenta L. Vacuum-assisted closure for the treatment of abdominal wounds. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33:213-224.

- Nienhuijs SW, Manupassa R, Strobbe LJ, et al. Can topical negative pressure be used to control complex enterocutaneous fistulae? J Wound Care. 2003;12:343-345.

- Alvarez AA, Maxwell GL, Rodriguez GC. Vacuum-assisted closure for cutaneous gastrointestinal fistula management. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;80:413-416.

- Erdmann D, Drye C, Heller L, et al. Abdominal wall defect and enterocutaneous fistula treatment with the Vacuum-Assisted Closure (V.A.C.) system. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:2066-2068.

- Schaffzin DM, Douglas JM, Stahl TJ, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure of complex perineal wounds. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1745-1748.

- Jethwa P, Lake SP. Using topical negative pressure therapy to resolve wound failure following perineal resection. J Wound Care. 2005;14:166-167.

- McGuinness JG, Winter DC, O’Connell PR. Vacuum-assisted closure of a complex pilonidal sinus. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:274-276.

- Steenvoorde P, van Engeland A. Oskam J. Vacuum-assisted closure therapy and oral anticoagulation therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:2220-2221.

- Negative pressure wound therapy: Morykwas approach [adverse events data]. Available at: www.npwt.com/morykwas.htm. Last accessed March 20, 2007.

- Carson SN, Overall K, Lee-Jahshan S, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure used for healing chronic wounds and skin grafts in the lower extremities. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2004;50:52-58.

- Gwan-Nulla D, Casal RS. Toxic shock syndrome associated with the use of the vacuum-assisted closure device. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;47:552-554.