User login

Hospital-level factors associated with pediatric emergency department return visits

Return visit (RV) rate is a quality measure commonly used in the emergency department (ED) setting. This metric may represent suboptimal care at the index ED visit.1-5 Although patient- and visit-level factors affecting ED RVs have been evaluated,1,3,4,6-9 hospital-level factors and factors of a hospital’s patient population that may play roles in ED RV rates have not been examined. Identifying the factors associated with increased RVs may allow resources to be designated to areas that improve emergent care for children.10

Hospital readmission rates are a closely followed quality measure and are linked to reimbursement by the federal government, but a recent study found the influence a hospital can have on this marker may be mitigated by the impact of the social determinates of health (SDHs) of the hospital’s patient population.11 That study and others have prompted an ongoing debate about adjusting quality measures for SDHs.12,13 A clearer understanding of these interactions may permit us to focus on factors that can truly lead to improvement in care instead of penalizing practitioners or hospitals that provide care to those most in need.

Prior work has identified several SDHs associated with higher ED RV rates in patient- or visit-level analyses.3,11,14 We conducted a study of hospital-level characteristics and characteristics of a hospital’s patient population to identify potentially mutable factors associated with increased ED RV rates that, once recognized, may allow for improvement in this quality measure.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This study was not considered human subjects research in accordance with Common Rule 45 CFR§46.104(f) and was evaluated by the Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital and Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine Institutional Review Boards and deemed exempt from review.

Study Population and Protocol

Our study had 2 data sources (to be described in detail): the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) and a survey of ED medical directors of the hospitals represented within PHIS. Hospitals were eligible for inclusion in the study if their data (1) met PHIS quality control standards for ED patient visits as determined by internal data assurance processes incorporated in PHIS,3,14,15 (2) included data only from an identifiable single main ED, and (3) completed the ED medical director’s survey.

PHIS Database

PHIS, an administrative database managed by Truven Health Analytics, includes data from ED, ambulatory surgery, observation, and inpatient encounters across Children’s Hospital Association member children’s hospitals in North America. Data are subjected to validity checks before being included in the database.16 PHIS assigns unique patient identifiers to track individual patient visits within participating institutions over time.

Hospitals were described by percentages of ED patients in several groups: age (<1, 1-4, 5-9, 10-14, and 15-18 years)17; sex; race/ethnicity; insurance type (commercial, government, other); ED International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition (ICD-9) diagnosis code–based severity classification system score (1-2, low severity; 3-5, high severity)18; complex

ED Medical Director Survey

A web-based survey was constructed in an iterative process based on literature review and expert opinion to assess hospital-level factors that may impact ED RV rates.3,7,24-26 The survey was piloted at 3 institutions to refine its structure and content.

The survey included 15 close-ended or multiple-choice questions on ED environment and operations and 2 open-ended questions, “What is the largest barrier to reducing the number of return visits within 72 hours of discharge from a previous ED visit?” and “In your opinion, what is the best way of reducing the number of the return visits within 72 hours of previous ED visit ?” (questionnaire in Supplemental material). Hospital characteristics from the survey included total clinical time allotment, or full-time equivalent (FTE), among all physicians, pediatric emergency medicine (PEM) fellowship-trained physicians, and all other (non-PEM) physicians. The data were standardized across sites by calculating FTE-per-10,000-visits values for each hospital; median duration of ED visit for admitted and discharged patients; median time from arrival to ED physician evaluation; rate of leaving without being seen; discharge educational material authorship and age specificity; follow-up visit scheduling procedure; and percentage of ED patients for whom English was a second language.

Responses to the 2 open-ended questions were independently categorized by Drs. Pittsenbarger and Alpern. Responses could be placed in more than 1 category if multiple answers to the question were included in the response. Categorizations were compared for consistency, and any inconsistencies were resolved by the consensus of the study investigators.

Outcome Measures From PHIS Database

All ED visits within a 12-month period (July 1, 2013–June 30, 2014) by patients younger than 18 years at time of index ED visit were eligible for inclusion in the study. An index visit was defined as any ED visit without another ED visit within the preceding 72 hours. The 72-hour time frame was used because it is the most widely studied time frame for ED RVs.5 Index ED visits that led to admission, observation status, death, or transfer were excluded.

The 2 primary outcomes of interest were (1) RVs within 72 hours of index ED visit discharge and (2) RVs within 72 hours that resulted in hospital admission or observation status at the next ED visit (RVA).7,9,27-30 For patients with multiple ED revisits within 72 hours, only the first was assessed. There was a 72-hour minimum between index visits for the same patient.

Statistical Analyses

To determine hospital groups based on RV and RVA rates, we adjusted RV and RVA rates using generalized linear mixed-effects models, controlling for clustering and allowing for correlated data (within hospitals), nonconstant variability (across hospitals), and non-normally distributed data, as we did in a study of patient-level factors associated with ED RV and RVA.3 For each calculated rate (RV, RVA), the hospitals were then classified into 3 groups based on whether the hospital’s adjusted RV and RVA rates were outside 2 SDs from the mean, below the 5th or above the 95th percentile, or within that range. These groups were labeled lowest outliers, highest outliers, and average-performing hospitals.

After the groups of hospitals were determined, we returned to using unadjusted data to statistically analyze them. We summarized continuous variables using minimum and maximum values, medians, and interquartile ranges (IQRs). We present categorical variables using counts and percentages. To identify hospital characteristics with the most potential to gain from improvement, we also analyzed associations using 2 collapsed groups: hospitals with RV (or RVA) rates included in the average-performing and lowest outlier groups and hospitals within the highest outlier group. Hospital characteristics and hospital’s patient population characteristics from the surveys are summarized based on RV and RVA rate groups. Differences in distributions among continuous variables were assessed by Kruskal-Wallis 1-way analysis of variance. Chi-square tests were used to evaluate differences in proportions among categorical variables. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute); 2-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Return Visit Rates and Hospital ED Site Population Characteristics

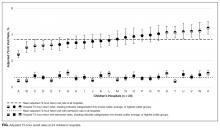

Twenty-four of 35 (68%) eligible hospitals that met PHIS quality control standards for ED patient visits responded to the ED medical director survey. The included hospitals that both met quality control standards and completed the survey had a total of 1,456,377 patient visits during the study period. Individual sites had annual volumes ranging from 26,627 to 96,637 ED encounters. The mean RV rate across the institutions was 3.7% (range, 3.0%-4.8%), and the mean RVA rate across the hospitals was 0.7% (range, 0.5%-1.1%) (Figure).

There were 5 hospitals with RV rates less than 2 SDs of the mean rate, placing them in the lowest outlier group for RV; 13 hospitals with RV rates within 2 SDs of the mean RV rate, placing them in the average-performing group; and 6 hospitals with RV rates above 2 SDs of the mean, placing them in the highest outlier group. Table 1 lists the hospital ED site population characteristics among the 3 RV rate groups. Hospitals in the highest outlier group served populations with higher proportions of patients with insurance from a government payer, lower proportions of patients covered by a commercial insurance plan, and higher proportion of patients with lower median household incomes.

In the RVA analysis, there were 6 hospitals with RVA rates less than 2 SDs of the mean RVA rate (lowest outliers); 14 hospitals with RVA rates within 2 SDs of the mean RVA rate (average performers); and 4 hospitals with RVA rates above 2 SDs of the mean RVA rate (highest outliers). When using these groups based on RVA rate, there were no statistically significant differences in hospital ED site population characteristics (Supplemental Table 1).

RV Rates and Hospital-Level Factors Survey Characteristics

Table 2 lists the ED medical director survey hospital-level data among the 3 RV rate groups. There were fewer FTEs by PEM fellowship-trained physicians per 10,000 patient visits at sites with higher RV rates (Table 2). Hospital-level characteristics assessed by the survey were not associated with RVA rates (Supplemental Table 2).

Evaluating characteristics of hospitals with the most potential to gain from improvement, hospitals with the highest RV rates (highest outlier group), compared with hospitals in the lowest outlier and average-performing groups collapsed together, persisted in having fewer PEM fellowship-trained physician FTEs per patient visit (Table 3). A similar collapsed analysis of RVA rates demonstrated that hospitals in the highest outlier group had longer-wait-to-physician time (81 minutes; IQR, 51-105 minutes) compared with hospitals in the other 2 groups (30 minutes; IQR, 19-42.5 minutes) (Table 3).

In response to the first qualitative question on the ED medial director survey, “In your opinion, what is the largest barrier to reducing the number of return visits within 72 hours of discharge from a previous ED visit?”, 15 directors (62.5%) reported limited access to primary care, 4 (16.6%) reported inadequate discharge instructions and/or education provided, and 3 (12.5%) reported lack of access to specialist care. To the second question, “In your opinion, what is the best way of reducing the number of the return visits within 72 hours of previous ED visit for the same condition?”, they responded that RVs could be reduced by innovations in scheduling primary care or specialty follow-up visits (19, 79%), improving discharge education and instructions (6, 25%), and identifying more case management or care coordination (4, 16.6%).

DISCUSSION

Other studies have identified patient- and visit-level characteristics associated with higher ED RV and RVA rates.3,8,9,31 However, as our goal was to identify possible modifiable institutional features, our study examined factors at hospital and population-served levels (instead of patient or visit level) that may impact ED RV and RVA rates. Interestingly, our sample of tertiary-care pediatric center EDs provided evidence of variability in RV and RVA rates. We identified factors associated with RV rates related to the SDHs of the populations served by the ED, which suggests these factors are not modifiable at an institution level. In addition, we found that the increased availability of PEM providers per patient visit correlated with fewer ED RVs.

Hospitals serving ED populations with more government-insured and fewer commercially insured patients had higher rates of return to the ED. Similarly, hospitals with larger proportions of patients from areas with lower median household incomes had higher RV rates. These factors may indicate that patients with limited resources may have more frequent ED RVs,3,6,32,33 and hospitals that serve them have higher ED RV rates. Our findings complement those of a recent study by Sills et al.,11 who evaluated hospital readmissions and proposed risk adjustment for performance reimbursement. This study found that hospital population-level race, ethnicity, insurance status, and household income were predictors of hospital readmission after discharge.

Of note, our data did not identify similar site-level attributes related to the population served that correlated with RVA rates. We postulate that the need for admission on RV may indicate an inherent clinical urgency or medical need associated with the return to the ED, whereas RV without admission may be related more to patient- or population-level sociodemographic factors than to quality of care and clinical course, which influence ED utilization.1,3,30 EDs treating higher proportions of patients of minority race or ethnicity, those with fewer financial resources, and those in more need of government health insurance are at higher risk for ED revisits.

We observed that increased PEM fellowship-trained physician staffing was associated with decreased RV rates. The availability of specialty-trained physicians in PEM may allow a larger proportion of patients treated by physicians with honed clinical skills for the patient population. Data from a single pediatric center showed PEM fellowship-trained physicians had admission rates lower than those of their counterparts without subspecialty fellowship training.34 The lower RV rate for this group in our study is especially interesting in light of previously reported lower admission rates at index visit in PEM trained physicians. With lower index admission rates, it may have been assumed that visits associated with PEM trained physician care would have an increased (rather than decreased) chance of RV. In addition, we noted the increased RVA rates were associated with longer waits to see a physician. These measures may indicate the effect of institutional access to robust resources (the ability to hire and support more specialty-trained physicians). These novel findings warrant further evaluation, particularly as our sample included only pediatric centers.

Our survey data demonstrated the impact that access to care has on ED RV rates. The ED medical directors indicated that limited access to outpatient appointments with PCPs and specialists was an important factor increasing ED RVs and a potential avenue for interventions. As the 2 open-ended questions addressed barriers and potential solutions, it is interesting that the respondents cited access to care and discharge instructions as the largest barriers and identified innovations in access to care and discharge education as important potential remedies.

This study demonstrated that, at the hospital level, ED RV quality measures are influenced by complex and varied SDHs that primarily reflect the characteristics of the patient populations served. Prior work has similarly highlighted the importance of gaining a rigorous understanding of other quality measures before widespread use, reporting, and dissemination of results.11,35-38 With this in mind, as quality measures are developed and implemented, care should be taken to ensure they accurately and appropriately reflect the quality of care provided to the patient and are not more representative of other factors not directly within institutional control. These findings call into question the usefulness of ED RVs as a quality measure for comparing institutions.

Study Limitations

This study had several limitations. The PHIS dataset tracks only patients within each institution and does not include RVs to other EDs, which may account for a proportion of RVs.39 Our survey response rate was 68% among medical directors, excluding 11 hospitals from analysis, which decreased the study’s power to detect differences that may be present between groups. In addition, the generalizability of our findings may be limited to tertiary-care children’s hospitals, as the PHIS dataset included only these types of healthcare facilities. We also included data only from the sites’ main EDs, and therefore cannot know if our results are applicable to satellite EDs. ED staffing of PEM physicians was analyzed using FTEs. However, number of clinical hours in 1 FTE may vary among sites, leading to imprecision in this hospital characteristic.

CONCLUSION

Hospitals with the highest RV rates served populations with a larger proportion of patients with government insurance and lower household income, and these hospitals had fewer PEM trained physicians. Variation in RV rates among hospitals may be indicative of the SDHs of their unique patient populations. ED revisit rates should be used cautiously in determining the quality of care of hospitals providing care to differing populations.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Goldman RD, Kapoor A, Mehta S. Children admitted to the hospital after returning to the emergency department within 72 hours. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(9):808-811. PubMed

2. Cho CS, Shapiro DJ, Cabana MD, Maselli JH, Hersh AL. A national depiction of children with return visits to the emergency department within 72 hours, 2001–2007. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(7):606-610. PubMed

3. Akenroye AT, Thurm CW, Neuman MI, et al. Prevalence and predictors of return visits to pediatric emergency departments. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(12):779-787. PubMed

4. Gallagher RA, Porter S, Monuteaux MC, Stack AM. Unscheduled return visits to the emergency department: the impact of language. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29(5):579-583. PubMed

5. Sørup CM, Jacobsen P, Forberg JL. Evaluation of emergency department performance—a systematic review on recommended performance and quality-in-care measures. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2013;21:62. PubMed

6. Gabayan GZ, Asch SM, Hsia RY, et al. Factors associated with short-term bounce-back admissions after emergency department discharge. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(2):136-144.e1. PubMed

7. Ali AB, Place R, Howell J, Malubay SM. Early pediatric emergency department return visits: a prospective patient-centric assessment. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2012;51(7):651-658. PubMed

8. Alessandrini EA, Lavelle JM, Grenfell SM, Jacobstein CR, Shaw KN. Return visits to a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004;20(3):166-171. PubMed

9. Goldman RD, Ong M, Macpherson A. Unscheduled return visits to the pediatric emergency department—one-year experience. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22(8):545-549. PubMed

10. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372-380. PubMed

11. Sills MR, Hall M, Colvin JD, et al. Association of social determinants with children’s hospitals’ preventable readmissions performance. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(4):350-358. PubMed

12. Fiscella K, Burstin HR, Nerenz DR. Quality measures and sociodemographic risk factors: to adjust or not to adjust. JAMA. 2014;312(24):2615-2616. PubMed

13. Lipstein SH, Dunagan WC. The risks of not adjusting performance measures for sociodemographic factors. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(8):594-596. PubMed

14. Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305(7):682-690. PubMed

15. Bourgeois FT, Monuteaux MC, Stack AM, Neuman MI. Variation in emergency department admission rates in US children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):539-545. PubMed

16. Fletcher DM. Achieving data quality. How data from a pediatric health information system earns the trust of its users. J AHIMA. 2004;75(10):22-26. PubMed

17. US Census Bureau. US Census current estimates data. 2014. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/data/data-sets.2014.html. Accessed June 2015.

18. Alessandrini EA, Alpern ER, Chamberlain JM, Shea JA, Gorelick MH. A new diagnosis grouping system for child emergency department visits. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(2):204-213. PubMed

19. Feudtner C, Levin JE, Srivastava R, et al. How well can hospital readmission be predicted in a cohort of hospitalized children? A retrospective, multicenter study. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):286-293. PubMed

20. Feinstein JA, Feudtner C, Kempe A. Adverse drug event–related emergency department visits associated with complex chronic conditions. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):e1575-e1585. PubMed

21. Simon TD, Berry J, Feudtner C, et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):647-655. PubMed

22. Dartmouth Medical School, Center for Evaluative Clinical Sciences. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Publishing; 2015.

23. Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, et al. Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA. 2011;306(15):1688-1698. PubMed

24. Lawrence LM, Jenkins CA, Zhou C, Givens TG. The effect of diagnosis-specific computerized discharge instructions on 72-hour return visits to the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25(11):733-738. PubMed

25. National Quality Forum. National Quality Forum issue brief: strengthening pediatric quality measurement and reporting. J Healthc Qual. 2008;30(3):51-55. PubMed

26. Rising KL, Victor TW, Hollander JE, Carr BG. Patient returns to the emergency department: the time-to-return curve. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(8):864-871. PubMed

27. Cho CS, Shapiro DJ, Cabana MD, Maselli JH, Hersh AL. A national depiction of children with return visits to the emergency department within 72 hours, 2001–2007. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(7):606-610. PubMed

28. Adekoya N. Patients seen in emergency departments who had a prior visit within the previous 72 h—National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2002. Public Health. 2005;119(10):914-918. PubMed

29. Mittal MK, Zorc JJ, Garcia-Espana JF, Shaw KN. An assessment of clinical performance measures for pediatric emergency physicians. Am J Med Qual. 2013;28(1):33-39. PubMed

30. Depiero AD, Ochsenschlager DW, Chamberlain JM. Analysis of pediatric hospitalizations after emergency department release as a quality improvement tool. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39(2):159-163. PubMed

31. Sung SF, Liu KE, Chen SC, Lo CL, Lin KC, Hu YH. Predicting factors and risk stratification for return visits to the emergency department within 72 hours in pediatric patients. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31(12):819-824. PubMed

32. Jacobstein CR, Alessandrini EA, Lavelle JM, Shaw KN. Unscheduled revisits to a pediatric emergency department: risk factors for children with fever or infection-related complaints. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2005;21(12):816-821. PubMed

33. Barnett ML, Hsu J, McWilliams J. Patient characteristics and differences in hospital readmission rates. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1803-1812. PubMed

34. Gaucher N, Bailey B, Gravel J. Impact of physicians’ characteristics on the admission risk among children visiting a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(2):120-124. PubMed

35. McHugh M, Neimeyer J, Powell E, Khare RK, Adams JG. An early look at performance on the emergency care measures included in Medicare’s hospital inpatient Value-Based Purchasing Program. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61(6):616-623.e2. PubMed

36. Axon RN, Williams MV. Hospital readmission as an accountability measure. JAMA. 2011;305(5):504-505. PubMed

37. Adams JG. Ensuring the quality of quality metrics for emergency care. JAMA. 2016;315(7):659-660. PubMed

38. Payne NR, Flood A. Preventing pediatric readmissions: which ones and how? J Pediatr. 2015;166(3):519-520. PubMed

39. Khan A, Nakamura MM, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Same-hospital readmission rates as a measure of pediatric quality of care. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(10):905-912. PubMed

Return visit (RV) rate is a quality measure commonly used in the emergency department (ED) setting. This metric may represent suboptimal care at the index ED visit.1-5 Although patient- and visit-level factors affecting ED RVs have been evaluated,1,3,4,6-9 hospital-level factors and factors of a hospital’s patient population that may play roles in ED RV rates have not been examined. Identifying the factors associated with increased RVs may allow resources to be designated to areas that improve emergent care for children.10

Hospital readmission rates are a closely followed quality measure and are linked to reimbursement by the federal government, but a recent study found the influence a hospital can have on this marker may be mitigated by the impact of the social determinates of health (SDHs) of the hospital’s patient population.11 That study and others have prompted an ongoing debate about adjusting quality measures for SDHs.12,13 A clearer understanding of these interactions may permit us to focus on factors that can truly lead to improvement in care instead of penalizing practitioners or hospitals that provide care to those most in need.

Prior work has identified several SDHs associated with higher ED RV rates in patient- or visit-level analyses.3,11,14 We conducted a study of hospital-level characteristics and characteristics of a hospital’s patient population to identify potentially mutable factors associated with increased ED RV rates that, once recognized, may allow for improvement in this quality measure.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This study was not considered human subjects research in accordance with Common Rule 45 CFR§46.104(f) and was evaluated by the Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital and Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine Institutional Review Boards and deemed exempt from review.

Study Population and Protocol

Our study had 2 data sources (to be described in detail): the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) and a survey of ED medical directors of the hospitals represented within PHIS. Hospitals were eligible for inclusion in the study if their data (1) met PHIS quality control standards for ED patient visits as determined by internal data assurance processes incorporated in PHIS,3,14,15 (2) included data only from an identifiable single main ED, and (3) completed the ED medical director’s survey.

PHIS Database

PHIS, an administrative database managed by Truven Health Analytics, includes data from ED, ambulatory surgery, observation, and inpatient encounters across Children’s Hospital Association member children’s hospitals in North America. Data are subjected to validity checks before being included in the database.16 PHIS assigns unique patient identifiers to track individual patient visits within participating institutions over time.

Hospitals were described by percentages of ED patients in several groups: age (<1, 1-4, 5-9, 10-14, and 15-18 years)17; sex; race/ethnicity; insurance type (commercial, government, other); ED International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition (ICD-9) diagnosis code–based severity classification system score (1-2, low severity; 3-5, high severity)18; complex

ED Medical Director Survey

A web-based survey was constructed in an iterative process based on literature review and expert opinion to assess hospital-level factors that may impact ED RV rates.3,7,24-26 The survey was piloted at 3 institutions to refine its structure and content.

The survey included 15 close-ended or multiple-choice questions on ED environment and operations and 2 open-ended questions, “What is the largest barrier to reducing the number of return visits within 72 hours of discharge from a previous ED visit?” and “In your opinion, what is the best way of reducing the number of the return visits within 72 hours of previous ED visit ?” (questionnaire in Supplemental material). Hospital characteristics from the survey included total clinical time allotment, or full-time equivalent (FTE), among all physicians, pediatric emergency medicine (PEM) fellowship-trained physicians, and all other (non-PEM) physicians. The data were standardized across sites by calculating FTE-per-10,000-visits values for each hospital; median duration of ED visit for admitted and discharged patients; median time from arrival to ED physician evaluation; rate of leaving without being seen; discharge educational material authorship and age specificity; follow-up visit scheduling procedure; and percentage of ED patients for whom English was a second language.

Responses to the 2 open-ended questions were independently categorized by Drs. Pittsenbarger and Alpern. Responses could be placed in more than 1 category if multiple answers to the question were included in the response. Categorizations were compared for consistency, and any inconsistencies were resolved by the consensus of the study investigators.

Outcome Measures From PHIS Database

All ED visits within a 12-month period (July 1, 2013–June 30, 2014) by patients younger than 18 years at time of index ED visit were eligible for inclusion in the study. An index visit was defined as any ED visit without another ED visit within the preceding 72 hours. The 72-hour time frame was used because it is the most widely studied time frame for ED RVs.5 Index ED visits that led to admission, observation status, death, or transfer were excluded.

The 2 primary outcomes of interest were (1) RVs within 72 hours of index ED visit discharge and (2) RVs within 72 hours that resulted in hospital admission or observation status at the next ED visit (RVA).7,9,27-30 For patients with multiple ED revisits within 72 hours, only the first was assessed. There was a 72-hour minimum between index visits for the same patient.

Statistical Analyses

To determine hospital groups based on RV and RVA rates, we adjusted RV and RVA rates using generalized linear mixed-effects models, controlling for clustering and allowing for correlated data (within hospitals), nonconstant variability (across hospitals), and non-normally distributed data, as we did in a study of patient-level factors associated with ED RV and RVA.3 For each calculated rate (RV, RVA), the hospitals were then classified into 3 groups based on whether the hospital’s adjusted RV and RVA rates were outside 2 SDs from the mean, below the 5th or above the 95th percentile, or within that range. These groups were labeled lowest outliers, highest outliers, and average-performing hospitals.

After the groups of hospitals were determined, we returned to using unadjusted data to statistically analyze them. We summarized continuous variables using minimum and maximum values, medians, and interquartile ranges (IQRs). We present categorical variables using counts and percentages. To identify hospital characteristics with the most potential to gain from improvement, we also analyzed associations using 2 collapsed groups: hospitals with RV (or RVA) rates included in the average-performing and lowest outlier groups and hospitals within the highest outlier group. Hospital characteristics and hospital’s patient population characteristics from the surveys are summarized based on RV and RVA rate groups. Differences in distributions among continuous variables were assessed by Kruskal-Wallis 1-way analysis of variance. Chi-square tests were used to evaluate differences in proportions among categorical variables. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute); 2-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Return Visit Rates and Hospital ED Site Population Characteristics

Twenty-four of 35 (68%) eligible hospitals that met PHIS quality control standards for ED patient visits responded to the ED medical director survey. The included hospitals that both met quality control standards and completed the survey had a total of 1,456,377 patient visits during the study period. Individual sites had annual volumes ranging from 26,627 to 96,637 ED encounters. The mean RV rate across the institutions was 3.7% (range, 3.0%-4.8%), and the mean RVA rate across the hospitals was 0.7% (range, 0.5%-1.1%) (Figure).

There were 5 hospitals with RV rates less than 2 SDs of the mean rate, placing them in the lowest outlier group for RV; 13 hospitals with RV rates within 2 SDs of the mean RV rate, placing them in the average-performing group; and 6 hospitals with RV rates above 2 SDs of the mean, placing them in the highest outlier group. Table 1 lists the hospital ED site population characteristics among the 3 RV rate groups. Hospitals in the highest outlier group served populations with higher proportions of patients with insurance from a government payer, lower proportions of patients covered by a commercial insurance plan, and higher proportion of patients with lower median household incomes.

In the RVA analysis, there were 6 hospitals with RVA rates less than 2 SDs of the mean RVA rate (lowest outliers); 14 hospitals with RVA rates within 2 SDs of the mean RVA rate (average performers); and 4 hospitals with RVA rates above 2 SDs of the mean RVA rate (highest outliers). When using these groups based on RVA rate, there were no statistically significant differences in hospital ED site population characteristics (Supplemental Table 1).

RV Rates and Hospital-Level Factors Survey Characteristics

Table 2 lists the ED medical director survey hospital-level data among the 3 RV rate groups. There were fewer FTEs by PEM fellowship-trained physicians per 10,000 patient visits at sites with higher RV rates (Table 2). Hospital-level characteristics assessed by the survey were not associated with RVA rates (Supplemental Table 2).

Evaluating characteristics of hospitals with the most potential to gain from improvement, hospitals with the highest RV rates (highest outlier group), compared with hospitals in the lowest outlier and average-performing groups collapsed together, persisted in having fewer PEM fellowship-trained physician FTEs per patient visit (Table 3). A similar collapsed analysis of RVA rates demonstrated that hospitals in the highest outlier group had longer-wait-to-physician time (81 minutes; IQR, 51-105 minutes) compared with hospitals in the other 2 groups (30 minutes; IQR, 19-42.5 minutes) (Table 3).

In response to the first qualitative question on the ED medial director survey, “In your opinion, what is the largest barrier to reducing the number of return visits within 72 hours of discharge from a previous ED visit?”, 15 directors (62.5%) reported limited access to primary care, 4 (16.6%) reported inadequate discharge instructions and/or education provided, and 3 (12.5%) reported lack of access to specialist care. To the second question, “In your opinion, what is the best way of reducing the number of the return visits within 72 hours of previous ED visit for the same condition?”, they responded that RVs could be reduced by innovations in scheduling primary care or specialty follow-up visits (19, 79%), improving discharge education and instructions (6, 25%), and identifying more case management or care coordination (4, 16.6%).

DISCUSSION

Other studies have identified patient- and visit-level characteristics associated with higher ED RV and RVA rates.3,8,9,31 However, as our goal was to identify possible modifiable institutional features, our study examined factors at hospital and population-served levels (instead of patient or visit level) that may impact ED RV and RVA rates. Interestingly, our sample of tertiary-care pediatric center EDs provided evidence of variability in RV and RVA rates. We identified factors associated with RV rates related to the SDHs of the populations served by the ED, which suggests these factors are not modifiable at an institution level. In addition, we found that the increased availability of PEM providers per patient visit correlated with fewer ED RVs.

Hospitals serving ED populations with more government-insured and fewer commercially insured patients had higher rates of return to the ED. Similarly, hospitals with larger proportions of patients from areas with lower median household incomes had higher RV rates. These factors may indicate that patients with limited resources may have more frequent ED RVs,3,6,32,33 and hospitals that serve them have higher ED RV rates. Our findings complement those of a recent study by Sills et al.,11 who evaluated hospital readmissions and proposed risk adjustment for performance reimbursement. This study found that hospital population-level race, ethnicity, insurance status, and household income were predictors of hospital readmission after discharge.

Of note, our data did not identify similar site-level attributes related to the population served that correlated with RVA rates. We postulate that the need for admission on RV may indicate an inherent clinical urgency or medical need associated with the return to the ED, whereas RV without admission may be related more to patient- or population-level sociodemographic factors than to quality of care and clinical course, which influence ED utilization.1,3,30 EDs treating higher proportions of patients of minority race or ethnicity, those with fewer financial resources, and those in more need of government health insurance are at higher risk for ED revisits.

We observed that increased PEM fellowship-trained physician staffing was associated with decreased RV rates. The availability of specialty-trained physicians in PEM may allow a larger proportion of patients treated by physicians with honed clinical skills for the patient population. Data from a single pediatric center showed PEM fellowship-trained physicians had admission rates lower than those of their counterparts without subspecialty fellowship training.34 The lower RV rate for this group in our study is especially interesting in light of previously reported lower admission rates at index visit in PEM trained physicians. With lower index admission rates, it may have been assumed that visits associated with PEM trained physician care would have an increased (rather than decreased) chance of RV. In addition, we noted the increased RVA rates were associated with longer waits to see a physician. These measures may indicate the effect of institutional access to robust resources (the ability to hire and support more specialty-trained physicians). These novel findings warrant further evaluation, particularly as our sample included only pediatric centers.

Our survey data demonstrated the impact that access to care has on ED RV rates. The ED medical directors indicated that limited access to outpatient appointments with PCPs and specialists was an important factor increasing ED RVs and a potential avenue for interventions. As the 2 open-ended questions addressed barriers and potential solutions, it is interesting that the respondents cited access to care and discharge instructions as the largest barriers and identified innovations in access to care and discharge education as important potential remedies.

This study demonstrated that, at the hospital level, ED RV quality measures are influenced by complex and varied SDHs that primarily reflect the characteristics of the patient populations served. Prior work has similarly highlighted the importance of gaining a rigorous understanding of other quality measures before widespread use, reporting, and dissemination of results.11,35-38 With this in mind, as quality measures are developed and implemented, care should be taken to ensure they accurately and appropriately reflect the quality of care provided to the patient and are not more representative of other factors not directly within institutional control. These findings call into question the usefulness of ED RVs as a quality measure for comparing institutions.

Study Limitations

This study had several limitations. The PHIS dataset tracks only patients within each institution and does not include RVs to other EDs, which may account for a proportion of RVs.39 Our survey response rate was 68% among medical directors, excluding 11 hospitals from analysis, which decreased the study’s power to detect differences that may be present between groups. In addition, the generalizability of our findings may be limited to tertiary-care children’s hospitals, as the PHIS dataset included only these types of healthcare facilities. We also included data only from the sites’ main EDs, and therefore cannot know if our results are applicable to satellite EDs. ED staffing of PEM physicians was analyzed using FTEs. However, number of clinical hours in 1 FTE may vary among sites, leading to imprecision in this hospital characteristic.

CONCLUSION

Hospitals with the highest RV rates served populations with a larger proportion of patients with government insurance and lower household income, and these hospitals had fewer PEM trained physicians. Variation in RV rates among hospitals may be indicative of the SDHs of their unique patient populations. ED revisit rates should be used cautiously in determining the quality of care of hospitals providing care to differing populations.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Return visit (RV) rate is a quality measure commonly used in the emergency department (ED) setting. This metric may represent suboptimal care at the index ED visit.1-5 Although patient- and visit-level factors affecting ED RVs have been evaluated,1,3,4,6-9 hospital-level factors and factors of a hospital’s patient population that may play roles in ED RV rates have not been examined. Identifying the factors associated with increased RVs may allow resources to be designated to areas that improve emergent care for children.10

Hospital readmission rates are a closely followed quality measure and are linked to reimbursement by the federal government, but a recent study found the influence a hospital can have on this marker may be mitigated by the impact of the social determinates of health (SDHs) of the hospital’s patient population.11 That study and others have prompted an ongoing debate about adjusting quality measures for SDHs.12,13 A clearer understanding of these interactions may permit us to focus on factors that can truly lead to improvement in care instead of penalizing practitioners or hospitals that provide care to those most in need.

Prior work has identified several SDHs associated with higher ED RV rates in patient- or visit-level analyses.3,11,14 We conducted a study of hospital-level characteristics and characteristics of a hospital’s patient population to identify potentially mutable factors associated with increased ED RV rates that, once recognized, may allow for improvement in this quality measure.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This study was not considered human subjects research in accordance with Common Rule 45 CFR§46.104(f) and was evaluated by the Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital and Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine Institutional Review Boards and deemed exempt from review.

Study Population and Protocol

Our study had 2 data sources (to be described in detail): the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) and a survey of ED medical directors of the hospitals represented within PHIS. Hospitals were eligible for inclusion in the study if their data (1) met PHIS quality control standards for ED patient visits as determined by internal data assurance processes incorporated in PHIS,3,14,15 (2) included data only from an identifiable single main ED, and (3) completed the ED medical director’s survey.

PHIS Database

PHIS, an administrative database managed by Truven Health Analytics, includes data from ED, ambulatory surgery, observation, and inpatient encounters across Children’s Hospital Association member children’s hospitals in North America. Data are subjected to validity checks before being included in the database.16 PHIS assigns unique patient identifiers to track individual patient visits within participating institutions over time.

Hospitals were described by percentages of ED patients in several groups: age (<1, 1-4, 5-9, 10-14, and 15-18 years)17; sex; race/ethnicity; insurance type (commercial, government, other); ED International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition (ICD-9) diagnosis code–based severity classification system score (1-2, low severity; 3-5, high severity)18; complex

ED Medical Director Survey

A web-based survey was constructed in an iterative process based on literature review and expert opinion to assess hospital-level factors that may impact ED RV rates.3,7,24-26 The survey was piloted at 3 institutions to refine its structure and content.

The survey included 15 close-ended or multiple-choice questions on ED environment and operations and 2 open-ended questions, “What is the largest barrier to reducing the number of return visits within 72 hours of discharge from a previous ED visit?” and “In your opinion, what is the best way of reducing the number of the return visits within 72 hours of previous ED visit ?” (questionnaire in Supplemental material). Hospital characteristics from the survey included total clinical time allotment, or full-time equivalent (FTE), among all physicians, pediatric emergency medicine (PEM) fellowship-trained physicians, and all other (non-PEM) physicians. The data were standardized across sites by calculating FTE-per-10,000-visits values for each hospital; median duration of ED visit for admitted and discharged patients; median time from arrival to ED physician evaluation; rate of leaving without being seen; discharge educational material authorship and age specificity; follow-up visit scheduling procedure; and percentage of ED patients for whom English was a second language.

Responses to the 2 open-ended questions were independently categorized by Drs. Pittsenbarger and Alpern. Responses could be placed in more than 1 category if multiple answers to the question were included in the response. Categorizations were compared for consistency, and any inconsistencies were resolved by the consensus of the study investigators.

Outcome Measures From PHIS Database

All ED visits within a 12-month period (July 1, 2013–June 30, 2014) by patients younger than 18 years at time of index ED visit were eligible for inclusion in the study. An index visit was defined as any ED visit without another ED visit within the preceding 72 hours. The 72-hour time frame was used because it is the most widely studied time frame for ED RVs.5 Index ED visits that led to admission, observation status, death, or transfer were excluded.

The 2 primary outcomes of interest were (1) RVs within 72 hours of index ED visit discharge and (2) RVs within 72 hours that resulted in hospital admission or observation status at the next ED visit (RVA).7,9,27-30 For patients with multiple ED revisits within 72 hours, only the first was assessed. There was a 72-hour minimum between index visits for the same patient.

Statistical Analyses

To determine hospital groups based on RV and RVA rates, we adjusted RV and RVA rates using generalized linear mixed-effects models, controlling for clustering and allowing for correlated data (within hospitals), nonconstant variability (across hospitals), and non-normally distributed data, as we did in a study of patient-level factors associated with ED RV and RVA.3 For each calculated rate (RV, RVA), the hospitals were then classified into 3 groups based on whether the hospital’s adjusted RV and RVA rates were outside 2 SDs from the mean, below the 5th or above the 95th percentile, or within that range. These groups were labeled lowest outliers, highest outliers, and average-performing hospitals.

After the groups of hospitals were determined, we returned to using unadjusted data to statistically analyze them. We summarized continuous variables using minimum and maximum values, medians, and interquartile ranges (IQRs). We present categorical variables using counts and percentages. To identify hospital characteristics with the most potential to gain from improvement, we also analyzed associations using 2 collapsed groups: hospitals with RV (or RVA) rates included in the average-performing and lowest outlier groups and hospitals within the highest outlier group. Hospital characteristics and hospital’s patient population characteristics from the surveys are summarized based on RV and RVA rate groups. Differences in distributions among continuous variables were assessed by Kruskal-Wallis 1-way analysis of variance. Chi-square tests were used to evaluate differences in proportions among categorical variables. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute); 2-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Return Visit Rates and Hospital ED Site Population Characteristics

Twenty-four of 35 (68%) eligible hospitals that met PHIS quality control standards for ED patient visits responded to the ED medical director survey. The included hospitals that both met quality control standards and completed the survey had a total of 1,456,377 patient visits during the study period. Individual sites had annual volumes ranging from 26,627 to 96,637 ED encounters. The mean RV rate across the institutions was 3.7% (range, 3.0%-4.8%), and the mean RVA rate across the hospitals was 0.7% (range, 0.5%-1.1%) (Figure).

There were 5 hospitals with RV rates less than 2 SDs of the mean rate, placing them in the lowest outlier group for RV; 13 hospitals with RV rates within 2 SDs of the mean RV rate, placing them in the average-performing group; and 6 hospitals with RV rates above 2 SDs of the mean, placing them in the highest outlier group. Table 1 lists the hospital ED site population characteristics among the 3 RV rate groups. Hospitals in the highest outlier group served populations with higher proportions of patients with insurance from a government payer, lower proportions of patients covered by a commercial insurance plan, and higher proportion of patients with lower median household incomes.

In the RVA analysis, there were 6 hospitals with RVA rates less than 2 SDs of the mean RVA rate (lowest outliers); 14 hospitals with RVA rates within 2 SDs of the mean RVA rate (average performers); and 4 hospitals with RVA rates above 2 SDs of the mean RVA rate (highest outliers). When using these groups based on RVA rate, there were no statistically significant differences in hospital ED site population characteristics (Supplemental Table 1).

RV Rates and Hospital-Level Factors Survey Characteristics

Table 2 lists the ED medical director survey hospital-level data among the 3 RV rate groups. There were fewer FTEs by PEM fellowship-trained physicians per 10,000 patient visits at sites with higher RV rates (Table 2). Hospital-level characteristics assessed by the survey were not associated with RVA rates (Supplemental Table 2).

Evaluating characteristics of hospitals with the most potential to gain from improvement, hospitals with the highest RV rates (highest outlier group), compared with hospitals in the lowest outlier and average-performing groups collapsed together, persisted in having fewer PEM fellowship-trained physician FTEs per patient visit (Table 3). A similar collapsed analysis of RVA rates demonstrated that hospitals in the highest outlier group had longer-wait-to-physician time (81 minutes; IQR, 51-105 minutes) compared with hospitals in the other 2 groups (30 minutes; IQR, 19-42.5 minutes) (Table 3).

In response to the first qualitative question on the ED medial director survey, “In your opinion, what is the largest barrier to reducing the number of return visits within 72 hours of discharge from a previous ED visit?”, 15 directors (62.5%) reported limited access to primary care, 4 (16.6%) reported inadequate discharge instructions and/or education provided, and 3 (12.5%) reported lack of access to specialist care. To the second question, “In your opinion, what is the best way of reducing the number of the return visits within 72 hours of previous ED visit for the same condition?”, they responded that RVs could be reduced by innovations in scheduling primary care or specialty follow-up visits (19, 79%), improving discharge education and instructions (6, 25%), and identifying more case management or care coordination (4, 16.6%).

DISCUSSION

Other studies have identified patient- and visit-level characteristics associated with higher ED RV and RVA rates.3,8,9,31 However, as our goal was to identify possible modifiable institutional features, our study examined factors at hospital and population-served levels (instead of patient or visit level) that may impact ED RV and RVA rates. Interestingly, our sample of tertiary-care pediatric center EDs provided evidence of variability in RV and RVA rates. We identified factors associated with RV rates related to the SDHs of the populations served by the ED, which suggests these factors are not modifiable at an institution level. In addition, we found that the increased availability of PEM providers per patient visit correlated with fewer ED RVs.

Hospitals serving ED populations with more government-insured and fewer commercially insured patients had higher rates of return to the ED. Similarly, hospitals with larger proportions of patients from areas with lower median household incomes had higher RV rates. These factors may indicate that patients with limited resources may have more frequent ED RVs,3,6,32,33 and hospitals that serve them have higher ED RV rates. Our findings complement those of a recent study by Sills et al.,11 who evaluated hospital readmissions and proposed risk adjustment for performance reimbursement. This study found that hospital population-level race, ethnicity, insurance status, and household income were predictors of hospital readmission after discharge.

Of note, our data did not identify similar site-level attributes related to the population served that correlated with RVA rates. We postulate that the need for admission on RV may indicate an inherent clinical urgency or medical need associated with the return to the ED, whereas RV without admission may be related more to patient- or population-level sociodemographic factors than to quality of care and clinical course, which influence ED utilization.1,3,30 EDs treating higher proportions of patients of minority race or ethnicity, those with fewer financial resources, and those in more need of government health insurance are at higher risk for ED revisits.

We observed that increased PEM fellowship-trained physician staffing was associated with decreased RV rates. The availability of specialty-trained physicians in PEM may allow a larger proportion of patients treated by physicians with honed clinical skills for the patient population. Data from a single pediatric center showed PEM fellowship-trained physicians had admission rates lower than those of their counterparts without subspecialty fellowship training.34 The lower RV rate for this group in our study is especially interesting in light of previously reported lower admission rates at index visit in PEM trained physicians. With lower index admission rates, it may have been assumed that visits associated with PEM trained physician care would have an increased (rather than decreased) chance of RV. In addition, we noted the increased RVA rates were associated with longer waits to see a physician. These measures may indicate the effect of institutional access to robust resources (the ability to hire and support more specialty-trained physicians). These novel findings warrant further evaluation, particularly as our sample included only pediatric centers.

Our survey data demonstrated the impact that access to care has on ED RV rates. The ED medical directors indicated that limited access to outpatient appointments with PCPs and specialists was an important factor increasing ED RVs and a potential avenue for interventions. As the 2 open-ended questions addressed barriers and potential solutions, it is interesting that the respondents cited access to care and discharge instructions as the largest barriers and identified innovations in access to care and discharge education as important potential remedies.

This study demonstrated that, at the hospital level, ED RV quality measures are influenced by complex and varied SDHs that primarily reflect the characteristics of the patient populations served. Prior work has similarly highlighted the importance of gaining a rigorous understanding of other quality measures before widespread use, reporting, and dissemination of results.11,35-38 With this in mind, as quality measures are developed and implemented, care should be taken to ensure they accurately and appropriately reflect the quality of care provided to the patient and are not more representative of other factors not directly within institutional control. These findings call into question the usefulness of ED RVs as a quality measure for comparing institutions.

Study Limitations

This study had several limitations. The PHIS dataset tracks only patients within each institution and does not include RVs to other EDs, which may account for a proportion of RVs.39 Our survey response rate was 68% among medical directors, excluding 11 hospitals from analysis, which decreased the study’s power to detect differences that may be present between groups. In addition, the generalizability of our findings may be limited to tertiary-care children’s hospitals, as the PHIS dataset included only these types of healthcare facilities. We also included data only from the sites’ main EDs, and therefore cannot know if our results are applicable to satellite EDs. ED staffing of PEM physicians was analyzed using FTEs. However, number of clinical hours in 1 FTE may vary among sites, leading to imprecision in this hospital characteristic.

CONCLUSION

Hospitals with the highest RV rates served populations with a larger proportion of patients with government insurance and lower household income, and these hospitals had fewer PEM trained physicians. Variation in RV rates among hospitals may be indicative of the SDHs of their unique patient populations. ED revisit rates should be used cautiously in determining the quality of care of hospitals providing care to differing populations.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Goldman RD, Kapoor A, Mehta S. Children admitted to the hospital after returning to the emergency department within 72 hours. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(9):808-811. PubMed

2. Cho CS, Shapiro DJ, Cabana MD, Maselli JH, Hersh AL. A national depiction of children with return visits to the emergency department within 72 hours, 2001–2007. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(7):606-610. PubMed

3. Akenroye AT, Thurm CW, Neuman MI, et al. Prevalence and predictors of return visits to pediatric emergency departments. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(12):779-787. PubMed

4. Gallagher RA, Porter S, Monuteaux MC, Stack AM. Unscheduled return visits to the emergency department: the impact of language. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29(5):579-583. PubMed

5. Sørup CM, Jacobsen P, Forberg JL. Evaluation of emergency department performance—a systematic review on recommended performance and quality-in-care measures. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2013;21:62. PubMed

6. Gabayan GZ, Asch SM, Hsia RY, et al. Factors associated with short-term bounce-back admissions after emergency department discharge. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(2):136-144.e1. PubMed

7. Ali AB, Place R, Howell J, Malubay SM. Early pediatric emergency department return visits: a prospective patient-centric assessment. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2012;51(7):651-658. PubMed

8. Alessandrini EA, Lavelle JM, Grenfell SM, Jacobstein CR, Shaw KN. Return visits to a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004;20(3):166-171. PubMed

9. Goldman RD, Ong M, Macpherson A. Unscheduled return visits to the pediatric emergency department—one-year experience. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22(8):545-549. PubMed

10. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372-380. PubMed

11. Sills MR, Hall M, Colvin JD, et al. Association of social determinants with children’s hospitals’ preventable readmissions performance. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(4):350-358. PubMed

12. Fiscella K, Burstin HR, Nerenz DR. Quality measures and sociodemographic risk factors: to adjust or not to adjust. JAMA. 2014;312(24):2615-2616. PubMed

13. Lipstein SH, Dunagan WC. The risks of not adjusting performance measures for sociodemographic factors. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(8):594-596. PubMed

14. Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305(7):682-690. PubMed

15. Bourgeois FT, Monuteaux MC, Stack AM, Neuman MI. Variation in emergency department admission rates in US children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):539-545. PubMed

16. Fletcher DM. Achieving data quality. How data from a pediatric health information system earns the trust of its users. J AHIMA. 2004;75(10):22-26. PubMed

17. US Census Bureau. US Census current estimates data. 2014. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/data/data-sets.2014.html. Accessed June 2015.

18. Alessandrini EA, Alpern ER, Chamberlain JM, Shea JA, Gorelick MH. A new diagnosis grouping system for child emergency department visits. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(2):204-213. PubMed

19. Feudtner C, Levin JE, Srivastava R, et al. How well can hospital readmission be predicted in a cohort of hospitalized children? A retrospective, multicenter study. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):286-293. PubMed

20. Feinstein JA, Feudtner C, Kempe A. Adverse drug event–related emergency department visits associated with complex chronic conditions. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):e1575-e1585. PubMed

21. Simon TD, Berry J, Feudtner C, et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):647-655. PubMed

22. Dartmouth Medical School, Center for Evaluative Clinical Sciences. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Publishing; 2015.

23. Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, et al. Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA. 2011;306(15):1688-1698. PubMed

24. Lawrence LM, Jenkins CA, Zhou C, Givens TG. The effect of diagnosis-specific computerized discharge instructions on 72-hour return visits to the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25(11):733-738. PubMed

25. National Quality Forum. National Quality Forum issue brief: strengthening pediatric quality measurement and reporting. J Healthc Qual. 2008;30(3):51-55. PubMed

26. Rising KL, Victor TW, Hollander JE, Carr BG. Patient returns to the emergency department: the time-to-return curve. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(8):864-871. PubMed

27. Cho CS, Shapiro DJ, Cabana MD, Maselli JH, Hersh AL. A national depiction of children with return visits to the emergency department within 72 hours, 2001–2007. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(7):606-610. PubMed

28. Adekoya N. Patients seen in emergency departments who had a prior visit within the previous 72 h—National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2002. Public Health. 2005;119(10):914-918. PubMed

29. Mittal MK, Zorc JJ, Garcia-Espana JF, Shaw KN. An assessment of clinical performance measures for pediatric emergency physicians. Am J Med Qual. 2013;28(1):33-39. PubMed

30. Depiero AD, Ochsenschlager DW, Chamberlain JM. Analysis of pediatric hospitalizations after emergency department release as a quality improvement tool. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39(2):159-163. PubMed

31. Sung SF, Liu KE, Chen SC, Lo CL, Lin KC, Hu YH. Predicting factors and risk stratification for return visits to the emergency department within 72 hours in pediatric patients. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31(12):819-824. PubMed

32. Jacobstein CR, Alessandrini EA, Lavelle JM, Shaw KN. Unscheduled revisits to a pediatric emergency department: risk factors for children with fever or infection-related complaints. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2005;21(12):816-821. PubMed

33. Barnett ML, Hsu J, McWilliams J. Patient characteristics and differences in hospital readmission rates. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1803-1812. PubMed

34. Gaucher N, Bailey B, Gravel J. Impact of physicians’ characteristics on the admission risk among children visiting a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(2):120-124. PubMed

35. McHugh M, Neimeyer J, Powell E, Khare RK, Adams JG. An early look at performance on the emergency care measures included in Medicare’s hospital inpatient Value-Based Purchasing Program. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61(6):616-623.e2. PubMed

36. Axon RN, Williams MV. Hospital readmission as an accountability measure. JAMA. 2011;305(5):504-505. PubMed

37. Adams JG. Ensuring the quality of quality metrics for emergency care. JAMA. 2016;315(7):659-660. PubMed

38. Payne NR, Flood A. Preventing pediatric readmissions: which ones and how? J Pediatr. 2015;166(3):519-520. PubMed

39. Khan A, Nakamura MM, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Same-hospital readmission rates as a measure of pediatric quality of care. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(10):905-912. PubMed

1. Goldman RD, Kapoor A, Mehta S. Children admitted to the hospital after returning to the emergency department within 72 hours. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(9):808-811. PubMed

2. Cho CS, Shapiro DJ, Cabana MD, Maselli JH, Hersh AL. A national depiction of children with return visits to the emergency department within 72 hours, 2001–2007. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(7):606-610. PubMed

3. Akenroye AT, Thurm CW, Neuman MI, et al. Prevalence and predictors of return visits to pediatric emergency departments. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(12):779-787. PubMed

4. Gallagher RA, Porter S, Monuteaux MC, Stack AM. Unscheduled return visits to the emergency department: the impact of language. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29(5):579-583. PubMed

5. Sørup CM, Jacobsen P, Forberg JL. Evaluation of emergency department performance—a systematic review on recommended performance and quality-in-care measures. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2013;21:62. PubMed

6. Gabayan GZ, Asch SM, Hsia RY, et al. Factors associated with short-term bounce-back admissions after emergency department discharge. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(2):136-144.e1. PubMed

7. Ali AB, Place R, Howell J, Malubay SM. Early pediatric emergency department return visits: a prospective patient-centric assessment. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2012;51(7):651-658. PubMed

8. Alessandrini EA, Lavelle JM, Grenfell SM, Jacobstein CR, Shaw KN. Return visits to a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004;20(3):166-171. PubMed

9. Goldman RD, Ong M, Macpherson A. Unscheduled return visits to the pediatric emergency department—one-year experience. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22(8):545-549. PubMed

10. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372-380. PubMed

11. Sills MR, Hall M, Colvin JD, et al. Association of social determinants with children’s hospitals’ preventable readmissions performance. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(4):350-358. PubMed

12. Fiscella K, Burstin HR, Nerenz DR. Quality measures and sociodemographic risk factors: to adjust or not to adjust. JAMA. 2014;312(24):2615-2616. PubMed

13. Lipstein SH, Dunagan WC. The risks of not adjusting performance measures for sociodemographic factors. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(8):594-596. PubMed

14. Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305(7):682-690. PubMed

15. Bourgeois FT, Monuteaux MC, Stack AM, Neuman MI. Variation in emergency department admission rates in US children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2014;134(3):539-545. PubMed

16. Fletcher DM. Achieving data quality. How data from a pediatric health information system earns the trust of its users. J AHIMA. 2004;75(10):22-26. PubMed

17. US Census Bureau. US Census current estimates data. 2014. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/data/data-sets.2014.html. Accessed June 2015.

18. Alessandrini EA, Alpern ER, Chamberlain JM, Shea JA, Gorelick MH. A new diagnosis grouping system for child emergency department visits. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(2):204-213. PubMed

19. Feudtner C, Levin JE, Srivastava R, et al. How well can hospital readmission be predicted in a cohort of hospitalized children? A retrospective, multicenter study. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):286-293. PubMed

20. Feinstein JA, Feudtner C, Kempe A. Adverse drug event–related emergency department visits associated with complex chronic conditions. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):e1575-e1585. PubMed

21. Simon TD, Berry J, Feudtner C, et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):647-655. PubMed

22. Dartmouth Medical School, Center for Evaluative Clinical Sciences. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Publishing; 2015.

23. Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, et al. Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA. 2011;306(15):1688-1698. PubMed

24. Lawrence LM, Jenkins CA, Zhou C, Givens TG. The effect of diagnosis-specific computerized discharge instructions on 72-hour return visits to the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25(11):733-738. PubMed

25. National Quality Forum. National Quality Forum issue brief: strengthening pediatric quality measurement and reporting. J Healthc Qual. 2008;30(3):51-55. PubMed

26. Rising KL, Victor TW, Hollander JE, Carr BG. Patient returns to the emergency department: the time-to-return curve. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(8):864-871. PubMed

27. Cho CS, Shapiro DJ, Cabana MD, Maselli JH, Hersh AL. A national depiction of children with return visits to the emergency department within 72 hours, 2001–2007. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(7):606-610. PubMed

28. Adekoya N. Patients seen in emergency departments who had a prior visit within the previous 72 h—National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2002. Public Health. 2005;119(10):914-918. PubMed

29. Mittal MK, Zorc JJ, Garcia-Espana JF, Shaw KN. An assessment of clinical performance measures for pediatric emergency physicians. Am J Med Qual. 2013;28(1):33-39. PubMed

30. Depiero AD, Ochsenschlager DW, Chamberlain JM. Analysis of pediatric hospitalizations after emergency department release as a quality improvement tool. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39(2):159-163. PubMed

31. Sung SF, Liu KE, Chen SC, Lo CL, Lin KC, Hu YH. Predicting factors and risk stratification for return visits to the emergency department within 72 hours in pediatric patients. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31(12):819-824. PubMed

32. Jacobstein CR, Alessandrini EA, Lavelle JM, Shaw KN. Unscheduled revisits to a pediatric emergency department: risk factors for children with fever or infection-related complaints. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2005;21(12):816-821. PubMed

33. Barnett ML, Hsu J, McWilliams J. Patient characteristics and differences in hospital readmission rates. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1803-1812. PubMed

34. Gaucher N, Bailey B, Gravel J. Impact of physicians’ characteristics on the admission risk among children visiting a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(2):120-124. PubMed

35. McHugh M, Neimeyer J, Powell E, Khare RK, Adams JG. An early look at performance on the emergency care measures included in Medicare’s hospital inpatient Value-Based Purchasing Program. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61(6):616-623.e2. PubMed

36. Axon RN, Williams MV. Hospital readmission as an accountability measure. JAMA. 2011;305(5):504-505. PubMed

37. Adams JG. Ensuring the quality of quality metrics for emergency care. JAMA. 2016;315(7):659-660. PubMed

38. Payne NR, Flood A. Preventing pediatric readmissions: which ones and how? J Pediatr. 2015;166(3):519-520. PubMed

39. Khan A, Nakamura MM, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Same-hospital readmission rates as a measure of pediatric quality of care. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(10):905-912. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine