User login

Introducing Point-Counterpoint Perspectives in the Journal of Hospital Medicine

Providing high-quality, efficient, and evidence-based healthcare is a complicated and complex process. The right approach or path forward is not always clear. In medicine, decision-making inherently involves uncertainty; evidence may be lacking, or values or context may differ, and thus, reasonable clinicians may choose to make different decisions based on the same data.

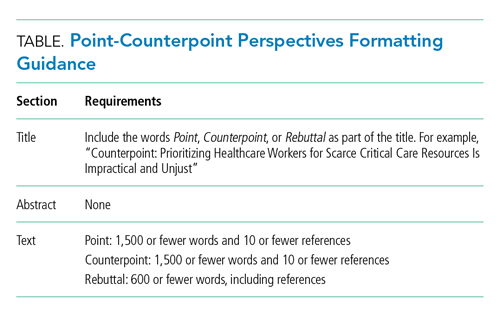

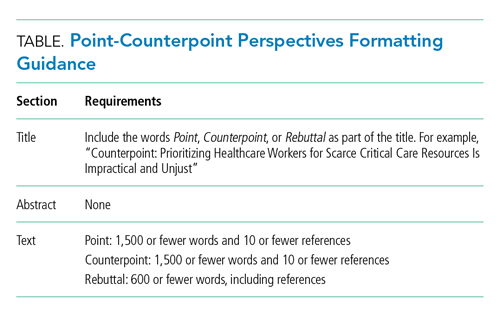

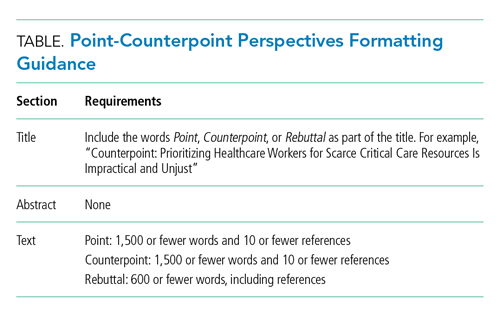

In this spirit of fostering education and healthy debate to improve understanding of challenges relevant to the field of hospital medicine, we are pleased to introduce our Point-Counterpoint series within the Perspectives in Hospital Medicine section of the journal. Point-Counterpoint Perspectives presents a debate by content experts. Each provides an interpretation of evidence regarding patient management or other controversial issues relating to hospital-based care. The format consists of an overview of the topic with an original point followed by a counterpoint response and, finally, a rebuttal (Table). We ask contributors to be as outspoken in their points and counterpoints as the evidence allows in order to fully elaborate the questions and uncertainties that may otherwise be familiar only to experts in the field or to those in other disciplines.

Our inaugural point-counterpoint articles address whether healthcare workers should receive priority for scarce drugs and therapies during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The intermittent shortage of medical supplies and protective equipment has made it not only difficult but also at times dangerous for healthcare workers to care for infected patients.1 The risks of developing COVID-19 and fear of transmitting it to loved ones has led to stress, fatigue, and burnout among healthcare workers, leading some to quit and even attempt suicide. The downstream effects of this stress may adversely affect patients and exacerbate staffing challenges in an already taxed healthcare system.2 Do we have a special obligation to those on the front lines? We are grateful to Drs Kirk R Daffner, Armand Antommaria, and Ndidi I Unaka, for addressing this controversial topic.3-5

1. Lagu T, Artenstein AW, Werner RM. Fool me twice: the role for hospitals and health systems in fixing the broken PPE supply chain. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):570-571. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3489

2. Ali SS. Why some nurses have quit during the coronavirus pandemic. NBC News. May,10, 2020. Accessed January 18, 2021. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/why-some-nurses-have-quit-during-coronavirus-pandemic-n1201796

3. Daffner KR. Point: healthcare providers should receive treatment priority during a pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):180-181. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3596

4. Antommaria A, Unaka NI. Counterpoint: prioritizing healthcare workers for scarce critical resources is impractical and unjust. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):182-183. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3597

5. Daffner KR. Rebuttal: accounting for the community’s reciprocal obligations during a pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):184. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3600

Providing high-quality, efficient, and evidence-based healthcare is a complicated and complex process. The right approach or path forward is not always clear. In medicine, decision-making inherently involves uncertainty; evidence may be lacking, or values or context may differ, and thus, reasonable clinicians may choose to make different decisions based on the same data.

In this spirit of fostering education and healthy debate to improve understanding of challenges relevant to the field of hospital medicine, we are pleased to introduce our Point-Counterpoint series within the Perspectives in Hospital Medicine section of the journal. Point-Counterpoint Perspectives presents a debate by content experts. Each provides an interpretation of evidence regarding patient management or other controversial issues relating to hospital-based care. The format consists of an overview of the topic with an original point followed by a counterpoint response and, finally, a rebuttal (Table). We ask contributors to be as outspoken in their points and counterpoints as the evidence allows in order to fully elaborate the questions and uncertainties that may otherwise be familiar only to experts in the field or to those in other disciplines.

Our inaugural point-counterpoint articles address whether healthcare workers should receive priority for scarce drugs and therapies during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The intermittent shortage of medical supplies and protective equipment has made it not only difficult but also at times dangerous for healthcare workers to care for infected patients.1 The risks of developing COVID-19 and fear of transmitting it to loved ones has led to stress, fatigue, and burnout among healthcare workers, leading some to quit and even attempt suicide. The downstream effects of this stress may adversely affect patients and exacerbate staffing challenges in an already taxed healthcare system.2 Do we have a special obligation to those on the front lines? We are grateful to Drs Kirk R Daffner, Armand Antommaria, and Ndidi I Unaka, for addressing this controversial topic.3-5

Providing high-quality, efficient, and evidence-based healthcare is a complicated and complex process. The right approach or path forward is not always clear. In medicine, decision-making inherently involves uncertainty; evidence may be lacking, or values or context may differ, and thus, reasonable clinicians may choose to make different decisions based on the same data.

In this spirit of fostering education and healthy debate to improve understanding of challenges relevant to the field of hospital medicine, we are pleased to introduce our Point-Counterpoint series within the Perspectives in Hospital Medicine section of the journal. Point-Counterpoint Perspectives presents a debate by content experts. Each provides an interpretation of evidence regarding patient management or other controversial issues relating to hospital-based care. The format consists of an overview of the topic with an original point followed by a counterpoint response and, finally, a rebuttal (Table). We ask contributors to be as outspoken in their points and counterpoints as the evidence allows in order to fully elaborate the questions and uncertainties that may otherwise be familiar only to experts in the field or to those in other disciplines.

Our inaugural point-counterpoint articles address whether healthcare workers should receive priority for scarce drugs and therapies during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The intermittent shortage of medical supplies and protective equipment has made it not only difficult but also at times dangerous for healthcare workers to care for infected patients.1 The risks of developing COVID-19 and fear of transmitting it to loved ones has led to stress, fatigue, and burnout among healthcare workers, leading some to quit and even attempt suicide. The downstream effects of this stress may adversely affect patients and exacerbate staffing challenges in an already taxed healthcare system.2 Do we have a special obligation to those on the front lines? We are grateful to Drs Kirk R Daffner, Armand Antommaria, and Ndidi I Unaka, for addressing this controversial topic.3-5

1. Lagu T, Artenstein AW, Werner RM. Fool me twice: the role for hospitals and health systems in fixing the broken PPE supply chain. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):570-571. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3489

2. Ali SS. Why some nurses have quit during the coronavirus pandemic. NBC News. May,10, 2020. Accessed January 18, 2021. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/why-some-nurses-have-quit-during-coronavirus-pandemic-n1201796

3. Daffner KR. Point: healthcare providers should receive treatment priority during a pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):180-181. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3596

4. Antommaria A, Unaka NI. Counterpoint: prioritizing healthcare workers for scarce critical resources is impractical and unjust. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):182-183. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3597

5. Daffner KR. Rebuttal: accounting for the community’s reciprocal obligations during a pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):184. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3600

1. Lagu T, Artenstein AW, Werner RM. Fool me twice: the role for hospitals and health systems in fixing the broken PPE supply chain. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):570-571. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3489

2. Ali SS. Why some nurses have quit during the coronavirus pandemic. NBC News. May,10, 2020. Accessed January 18, 2021. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/why-some-nurses-have-quit-during-coronavirus-pandemic-n1201796

3. Daffner KR. Point: healthcare providers should receive treatment priority during a pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):180-181. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3596

4. Antommaria A, Unaka NI. Counterpoint: prioritizing healthcare workers for scarce critical resources is impractical and unjust. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):182-183. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3597

5. Daffner KR. Rebuttal: accounting for the community’s reciprocal obligations during a pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):184. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3600

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

The Light at the End of the Tunnel: Reflections on 2020 and Hopes for 2021

We enter the new year still in the midst of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and remain humbled by its impact. It is remarkable how much, and how little, has changed. Hospitalists in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic were struggling. We were caring for patients who were suffering and dying from a new and mysterious disease. There weren’t enough tests (or, if there were tests, there weren’t swabs).1 We were using protocols for managing respiratory failure that, we would learn later, may not have been the best for improving outcomes. Rumors of unproven therapies came from everywhere: our patients, our colleagues, and even the highest realms of the federal government. We also knew very little about how best to protect ourselves. In many cases, we did not have enough personal protective equipment (PPE). There were no face shields, or “zoom rounds,” or even awareness that we probably shouldn’t sit in the tiny conference room (maskless) discussing patients with the large team of doctors, nurses, respiratory therapists, and social workers.

Perhaps worst of all, we were haunted. We were alarmed by the large numbers of young patients who were ill, and our elderly patients, many of whom we knew and had cared for many times, had suddenly just stopped showing up.2 In our free moments, we worried about them; maybe they were afraid to come to the hospital, maybe they were home sick with COVID-19, or maybe they had died alone. And children, initially thought to be spared the most serious consequences of COVID-19, started coming to the hospital with a rare but severe new COVID-19-associated complication, termed multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). We had to learn to manage yet another manifestation of COVID-19, largely through trial and error.

And, of course, clinical care was only one of our many responsibilities. We were also busy hunting for ventilators, setting up makeshift medical wards and intensive care units, revamping medical education, and scouring the literature for any information to help guide patient care. We worried about getting sick ourselves and bringing the disease home to our families. Our impatience grew as day after day there was no (and still is no) coordinated federal response.

A glimmer of hope slowly emerged. Our colleagues designed and rapidly evaluated respiratory protocols and provided early evidence about the strategies (eg, proning) that were associated with improved outcomes.3 Researchers began to generate knowledge and move us beyond rumors regarding potential therapies. We cheered as our administrators concocted unusual strategies to remedy the PPE and testing shortages.4

At the Journal of Hospital Medicine, we were faced with another challenge: How would we describe the chaos and the challenges of being a physician during the COVID-19 era? How would we document the way our colleagues were rising to the challenge and identifying opportunities to rethink hospital care in the United States?

In April, we began to receive a deluge of personal essays from frontline physicians about their experiences with COVID-19. Generally, medical journals publish and disseminate original, high-impact research. Personal essays rarely fit this model. Given the unprecedented circumstances, however, we decided these essays could help chronicle an important moment in medical history. In our May 2020 issue, we published only these essays. We continue to publish them online almost daily.

Some of the essays described how the healthcare system—previously thought to be hyperspecialized, profit-driven, and resistant to change—pivoted within days, as hospitalist physicians trained other physicians to “unspecialize” and pediatricians began to care for adults in an otherwise overwhelmed hospital system.5,6 Another essay focused on the need to trust that medical students who had graduated early would be able to function as physicians.7 And yet another essay expressed concern about the widespread use of unproven therapies in hospitalized patients. “Even in times of global pandemic, we need to consider potential harms and adverse consequences of novel treatments,’’ the physicians wrote. “Sometimes inaction is preferable to action.”8

Several essays reflected on the impact of the pandemic on healthcare disparities, suggesting that the pandemic had made (the well-known but often ignored) differences in health outcomes between White patients and racial minorities more obvious. Still another essay reflected on the intersection between structural racism, poor access to care, and interpersonal racism, describing the grief caused by losses of Black lives to both police violence and COVID-19.9

There also were personal stories of hardship and survival. One hospitalist physician with asthma described coughing as ``the new leprosy.”10 She wrote, “This is a particularly unpropitious time in history to be a Chinese-American doctor who can’t stop coughing.”

There were drawbacks to our decision to focus on personal essays. Although it was clear even before the pandemic, COVID-19 has highlighted that a path for quick dissemination of original peer-reviewed research is needed. If existing medical journals do not fill that role, websites that publish and disseminate non–peer-reviewed work (aka, “preprints”) will become the preferred method for distribution of high-impact, timely original research.11 The journal’s pivot to reviewing and publishing personal essays may have kept us from improving our approach to rapid peer review and dissemination. In those early days, however, there was no peer-reviewed work to publish, but there was an intense desire (from our members and physicians generally) for information and stories from the front lines. In a way, the essays we published were early “case reports,” that hypothesized about how we might rethink healthcare delivery in pandemic conditions.

Furthermore, our decision to solicit and publish personal essays addressing shortcomings of the federal response and consequences of the pandemic meant that the Journal of Hospital Medicine became part of the pandemic’s political discourse. As editors, we have historically kept the journal away from political arguments or endorsements. In this case, however, we decided that even if some of the opinions were political, they were an appropriate response to the widespread anti-science rhetoric endorsed by the current administration. The resultant erosion of trust in public health has undoubtedly contributed to persistence of the pandemic.12 A stance against masks, for example, rejects the recommendations of nearly all scientists in favor of (a selfish and problematic idea of) “self-determination.” Those who proclaim that such a mandate infringes on their personal freedom reject evidence-based recommendations of scientists and disregard public health strategies meant to protect everyone.

As we reflect on the past year, our most important lesson may be that our previous emphasis on publishing high-impact original research likely missed important personal and professional insights, insights that could have changed practice, improved patient experience, and reduced physician burnout. Anecdotes are not scientific evidence, but we have discovered their incredible power to help us learn, empathize, commiserate, and survive. Hospitals learned that they must adapt in the moment, a notion that runs counter to the notoriously slow pace of change in paradigms of healthcare. Hospitalists learned to “find their battle buddies” to ward off isolation and to cherish their teams in the face of overwhelming trauma, an approach requiring empathy, humility, and compassion.13 We won’t soon forget that, when things were most dire, it was stories—not data—that gave us hope. We look forward to 2021 with great optimism. New vaccines and new federal leaders who value and respect science give us hope that the end of the pandemic is in sight. We are indebted to all frontline workers who have transformed care delivery and remained courageous in the face of great personal risk. As a journal, we will continue, as one scientist noted, to use our “platform for advocacy, unabashedly.”14

1. Shuren J, Stenzel T. Covid-19 molecular diagnostic testing - lessons learned. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:e97. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2023830

2. Rosenbaum L. The untold toll - the pandemic’s effects on patients without Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2368-2371. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMms2009984

3. Westafer LM, Elia T, Medarametla V, Lagu T. A transdisciplinary COVID-19 early respiratory intervention protocol: an implementation story. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:372-374. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3456

4. Lagu T, Artenstein AW, Werner RM. Fool me twice: the role for hospitals and health systems in fixing the broken PPE supply chain. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:570-571. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3489

5. Cram P, Anderson ML, Shaughnessy EE. All hands on deck: learning to “un-specialize” in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:314-315. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3426

6. Biala D, Siegel EJ, Silver L, Schindel B, Smith KM. Deployed: pediatric residents caring for adults during COVID-19’s first wave in New York City. J Hosp Med. 2020; Published ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3527

7. Kinnear B, Kelleher M, Olson AP, Sall D, Schumacher DJ. Developing trust with early medical school graduates during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:367-369. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3463

8. Canfield GS, Schultz JS, Windham S, et al. Empiric therapies for covid-19: destined to fail by ignoring the lessons of history. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:434-436. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3469

9. Manning KD. When grief and crises intersect: perspectives of a Black physician in the time of two pandemics. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:566-567. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3481

10. Chang T. Do I have coronavirus? J Hosp Med. 2020;15:277-278. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3430

11. Guterman EL, Braunstein LZ. Preprints during the COVID-19 pandemic: public health emergencies and medical literature. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:634-636. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3491

12. Udow-Phillips M, Lantz PM. Trust in public health is essential amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:431-433. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3474

13. Hertling M. Ten tips for a crisis: lessons from a soldier. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:275-276. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3424

14. O’Glasser A [@aoglasser]. #JHMChat I also need to readily admit that part of the reason I’m a loyal, enthusiastic @JHospMedicine reader is because [Tweet]. November 16, 2020. Accessed November 28, 2020. https://twitter.com/aoglasser/status/1328529564595720192

We enter the new year still in the midst of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and remain humbled by its impact. It is remarkable how much, and how little, has changed. Hospitalists in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic were struggling. We were caring for patients who were suffering and dying from a new and mysterious disease. There weren’t enough tests (or, if there were tests, there weren’t swabs).1 We were using protocols for managing respiratory failure that, we would learn later, may not have been the best for improving outcomes. Rumors of unproven therapies came from everywhere: our patients, our colleagues, and even the highest realms of the federal government. We also knew very little about how best to protect ourselves. In many cases, we did not have enough personal protective equipment (PPE). There were no face shields, or “zoom rounds,” or even awareness that we probably shouldn’t sit in the tiny conference room (maskless) discussing patients with the large team of doctors, nurses, respiratory therapists, and social workers.

Perhaps worst of all, we were haunted. We were alarmed by the large numbers of young patients who were ill, and our elderly patients, many of whom we knew and had cared for many times, had suddenly just stopped showing up.2 In our free moments, we worried about them; maybe they were afraid to come to the hospital, maybe they were home sick with COVID-19, or maybe they had died alone. And children, initially thought to be spared the most serious consequences of COVID-19, started coming to the hospital with a rare but severe new COVID-19-associated complication, termed multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). We had to learn to manage yet another manifestation of COVID-19, largely through trial and error.

And, of course, clinical care was only one of our many responsibilities. We were also busy hunting for ventilators, setting up makeshift medical wards and intensive care units, revamping medical education, and scouring the literature for any information to help guide patient care. We worried about getting sick ourselves and bringing the disease home to our families. Our impatience grew as day after day there was no (and still is no) coordinated federal response.

A glimmer of hope slowly emerged. Our colleagues designed and rapidly evaluated respiratory protocols and provided early evidence about the strategies (eg, proning) that were associated with improved outcomes.3 Researchers began to generate knowledge and move us beyond rumors regarding potential therapies. We cheered as our administrators concocted unusual strategies to remedy the PPE and testing shortages.4

At the Journal of Hospital Medicine, we were faced with another challenge: How would we describe the chaos and the challenges of being a physician during the COVID-19 era? How would we document the way our colleagues were rising to the challenge and identifying opportunities to rethink hospital care in the United States?

In April, we began to receive a deluge of personal essays from frontline physicians about their experiences with COVID-19. Generally, medical journals publish and disseminate original, high-impact research. Personal essays rarely fit this model. Given the unprecedented circumstances, however, we decided these essays could help chronicle an important moment in medical history. In our May 2020 issue, we published only these essays. We continue to publish them online almost daily.

Some of the essays described how the healthcare system—previously thought to be hyperspecialized, profit-driven, and resistant to change—pivoted within days, as hospitalist physicians trained other physicians to “unspecialize” and pediatricians began to care for adults in an otherwise overwhelmed hospital system.5,6 Another essay focused on the need to trust that medical students who had graduated early would be able to function as physicians.7 And yet another essay expressed concern about the widespread use of unproven therapies in hospitalized patients. “Even in times of global pandemic, we need to consider potential harms and adverse consequences of novel treatments,’’ the physicians wrote. “Sometimes inaction is preferable to action.”8

Several essays reflected on the impact of the pandemic on healthcare disparities, suggesting that the pandemic had made (the well-known but often ignored) differences in health outcomes between White patients and racial minorities more obvious. Still another essay reflected on the intersection between structural racism, poor access to care, and interpersonal racism, describing the grief caused by losses of Black lives to both police violence and COVID-19.9

There also were personal stories of hardship and survival. One hospitalist physician with asthma described coughing as ``the new leprosy.”10 She wrote, “This is a particularly unpropitious time in history to be a Chinese-American doctor who can’t stop coughing.”

There were drawbacks to our decision to focus on personal essays. Although it was clear even before the pandemic, COVID-19 has highlighted that a path for quick dissemination of original peer-reviewed research is needed. If existing medical journals do not fill that role, websites that publish and disseminate non–peer-reviewed work (aka, “preprints”) will become the preferred method for distribution of high-impact, timely original research.11 The journal’s pivot to reviewing and publishing personal essays may have kept us from improving our approach to rapid peer review and dissemination. In those early days, however, there was no peer-reviewed work to publish, but there was an intense desire (from our members and physicians generally) for information and stories from the front lines. In a way, the essays we published were early “case reports,” that hypothesized about how we might rethink healthcare delivery in pandemic conditions.

Furthermore, our decision to solicit and publish personal essays addressing shortcomings of the federal response and consequences of the pandemic meant that the Journal of Hospital Medicine became part of the pandemic’s political discourse. As editors, we have historically kept the journal away from political arguments or endorsements. In this case, however, we decided that even if some of the opinions were political, they were an appropriate response to the widespread anti-science rhetoric endorsed by the current administration. The resultant erosion of trust in public health has undoubtedly contributed to persistence of the pandemic.12 A stance against masks, for example, rejects the recommendations of nearly all scientists in favor of (a selfish and problematic idea of) “self-determination.” Those who proclaim that such a mandate infringes on their personal freedom reject evidence-based recommendations of scientists and disregard public health strategies meant to protect everyone.

As we reflect on the past year, our most important lesson may be that our previous emphasis on publishing high-impact original research likely missed important personal and professional insights, insights that could have changed practice, improved patient experience, and reduced physician burnout. Anecdotes are not scientific evidence, but we have discovered their incredible power to help us learn, empathize, commiserate, and survive. Hospitals learned that they must adapt in the moment, a notion that runs counter to the notoriously slow pace of change in paradigms of healthcare. Hospitalists learned to “find their battle buddies” to ward off isolation and to cherish their teams in the face of overwhelming trauma, an approach requiring empathy, humility, and compassion.13 We won’t soon forget that, when things were most dire, it was stories—not data—that gave us hope. We look forward to 2021 with great optimism. New vaccines and new federal leaders who value and respect science give us hope that the end of the pandemic is in sight. We are indebted to all frontline workers who have transformed care delivery and remained courageous in the face of great personal risk. As a journal, we will continue, as one scientist noted, to use our “platform for advocacy, unabashedly.”14

We enter the new year still in the midst of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and remain humbled by its impact. It is remarkable how much, and how little, has changed. Hospitalists in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic were struggling. We were caring for patients who were suffering and dying from a new and mysterious disease. There weren’t enough tests (or, if there were tests, there weren’t swabs).1 We were using protocols for managing respiratory failure that, we would learn later, may not have been the best for improving outcomes. Rumors of unproven therapies came from everywhere: our patients, our colleagues, and even the highest realms of the federal government. We also knew very little about how best to protect ourselves. In many cases, we did not have enough personal protective equipment (PPE). There were no face shields, or “zoom rounds,” or even awareness that we probably shouldn’t sit in the tiny conference room (maskless) discussing patients with the large team of doctors, nurses, respiratory therapists, and social workers.

Perhaps worst of all, we were haunted. We were alarmed by the large numbers of young patients who were ill, and our elderly patients, many of whom we knew and had cared for many times, had suddenly just stopped showing up.2 In our free moments, we worried about them; maybe they were afraid to come to the hospital, maybe they were home sick with COVID-19, or maybe they had died alone. And children, initially thought to be spared the most serious consequences of COVID-19, started coming to the hospital with a rare but severe new COVID-19-associated complication, termed multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). We had to learn to manage yet another manifestation of COVID-19, largely through trial and error.

And, of course, clinical care was only one of our many responsibilities. We were also busy hunting for ventilators, setting up makeshift medical wards and intensive care units, revamping medical education, and scouring the literature for any information to help guide patient care. We worried about getting sick ourselves and bringing the disease home to our families. Our impatience grew as day after day there was no (and still is no) coordinated federal response.

A glimmer of hope slowly emerged. Our colleagues designed and rapidly evaluated respiratory protocols and provided early evidence about the strategies (eg, proning) that were associated with improved outcomes.3 Researchers began to generate knowledge and move us beyond rumors regarding potential therapies. We cheered as our administrators concocted unusual strategies to remedy the PPE and testing shortages.4

At the Journal of Hospital Medicine, we were faced with another challenge: How would we describe the chaos and the challenges of being a physician during the COVID-19 era? How would we document the way our colleagues were rising to the challenge and identifying opportunities to rethink hospital care in the United States?

In April, we began to receive a deluge of personal essays from frontline physicians about their experiences with COVID-19. Generally, medical journals publish and disseminate original, high-impact research. Personal essays rarely fit this model. Given the unprecedented circumstances, however, we decided these essays could help chronicle an important moment in medical history. In our May 2020 issue, we published only these essays. We continue to publish them online almost daily.

Some of the essays described how the healthcare system—previously thought to be hyperspecialized, profit-driven, and resistant to change—pivoted within days, as hospitalist physicians trained other physicians to “unspecialize” and pediatricians began to care for adults in an otherwise overwhelmed hospital system.5,6 Another essay focused on the need to trust that medical students who had graduated early would be able to function as physicians.7 And yet another essay expressed concern about the widespread use of unproven therapies in hospitalized patients. “Even in times of global pandemic, we need to consider potential harms and adverse consequences of novel treatments,’’ the physicians wrote. “Sometimes inaction is preferable to action.”8

Several essays reflected on the impact of the pandemic on healthcare disparities, suggesting that the pandemic had made (the well-known but often ignored) differences in health outcomes between White patients and racial minorities more obvious. Still another essay reflected on the intersection between structural racism, poor access to care, and interpersonal racism, describing the grief caused by losses of Black lives to both police violence and COVID-19.9

There also were personal stories of hardship and survival. One hospitalist physician with asthma described coughing as ``the new leprosy.”10 She wrote, “This is a particularly unpropitious time in history to be a Chinese-American doctor who can’t stop coughing.”

There were drawbacks to our decision to focus on personal essays. Although it was clear even before the pandemic, COVID-19 has highlighted that a path for quick dissemination of original peer-reviewed research is needed. If existing medical journals do not fill that role, websites that publish and disseminate non–peer-reviewed work (aka, “preprints”) will become the preferred method for distribution of high-impact, timely original research.11 The journal’s pivot to reviewing and publishing personal essays may have kept us from improving our approach to rapid peer review and dissemination. In those early days, however, there was no peer-reviewed work to publish, but there was an intense desire (from our members and physicians generally) for information and stories from the front lines. In a way, the essays we published were early “case reports,” that hypothesized about how we might rethink healthcare delivery in pandemic conditions.

Furthermore, our decision to solicit and publish personal essays addressing shortcomings of the federal response and consequences of the pandemic meant that the Journal of Hospital Medicine became part of the pandemic’s political discourse. As editors, we have historically kept the journal away from political arguments or endorsements. In this case, however, we decided that even if some of the opinions were political, they were an appropriate response to the widespread anti-science rhetoric endorsed by the current administration. The resultant erosion of trust in public health has undoubtedly contributed to persistence of the pandemic.12 A stance against masks, for example, rejects the recommendations of nearly all scientists in favor of (a selfish and problematic idea of) “self-determination.” Those who proclaim that such a mandate infringes on their personal freedom reject evidence-based recommendations of scientists and disregard public health strategies meant to protect everyone.

As we reflect on the past year, our most important lesson may be that our previous emphasis on publishing high-impact original research likely missed important personal and professional insights, insights that could have changed practice, improved patient experience, and reduced physician burnout. Anecdotes are not scientific evidence, but we have discovered their incredible power to help us learn, empathize, commiserate, and survive. Hospitals learned that they must adapt in the moment, a notion that runs counter to the notoriously slow pace of change in paradigms of healthcare. Hospitalists learned to “find their battle buddies” to ward off isolation and to cherish their teams in the face of overwhelming trauma, an approach requiring empathy, humility, and compassion.13 We won’t soon forget that, when things were most dire, it was stories—not data—that gave us hope. We look forward to 2021 with great optimism. New vaccines and new federal leaders who value and respect science give us hope that the end of the pandemic is in sight. We are indebted to all frontline workers who have transformed care delivery and remained courageous in the face of great personal risk. As a journal, we will continue, as one scientist noted, to use our “platform for advocacy, unabashedly.”14

1. Shuren J, Stenzel T. Covid-19 molecular diagnostic testing - lessons learned. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:e97. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2023830

2. Rosenbaum L. The untold toll - the pandemic’s effects on patients without Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2368-2371. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMms2009984

3. Westafer LM, Elia T, Medarametla V, Lagu T. A transdisciplinary COVID-19 early respiratory intervention protocol: an implementation story. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:372-374. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3456

4. Lagu T, Artenstein AW, Werner RM. Fool me twice: the role for hospitals and health systems in fixing the broken PPE supply chain. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:570-571. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3489

5. Cram P, Anderson ML, Shaughnessy EE. All hands on deck: learning to “un-specialize” in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:314-315. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3426

6. Biala D, Siegel EJ, Silver L, Schindel B, Smith KM. Deployed: pediatric residents caring for adults during COVID-19’s first wave in New York City. J Hosp Med. 2020; Published ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3527

7. Kinnear B, Kelleher M, Olson AP, Sall D, Schumacher DJ. Developing trust with early medical school graduates during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:367-369. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3463

8. Canfield GS, Schultz JS, Windham S, et al. Empiric therapies for covid-19: destined to fail by ignoring the lessons of history. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:434-436. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3469

9. Manning KD. When grief and crises intersect: perspectives of a Black physician in the time of two pandemics. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:566-567. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3481

10. Chang T. Do I have coronavirus? J Hosp Med. 2020;15:277-278. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3430

11. Guterman EL, Braunstein LZ. Preprints during the COVID-19 pandemic: public health emergencies and medical literature. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:634-636. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3491

12. Udow-Phillips M, Lantz PM. Trust in public health is essential amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:431-433. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3474

13. Hertling M. Ten tips for a crisis: lessons from a soldier. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:275-276. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3424

14. O’Glasser A [@aoglasser]. #JHMChat I also need to readily admit that part of the reason I’m a loyal, enthusiastic @JHospMedicine reader is because [Tweet]. November 16, 2020. Accessed November 28, 2020. https://twitter.com/aoglasser/status/1328529564595720192

1. Shuren J, Stenzel T. Covid-19 molecular diagnostic testing - lessons learned. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:e97. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2023830

2. Rosenbaum L. The untold toll - the pandemic’s effects on patients without Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2368-2371. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMms2009984

3. Westafer LM, Elia T, Medarametla V, Lagu T. A transdisciplinary COVID-19 early respiratory intervention protocol: an implementation story. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:372-374. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3456

4. Lagu T, Artenstein AW, Werner RM. Fool me twice: the role for hospitals and health systems in fixing the broken PPE supply chain. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:570-571. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3489

5. Cram P, Anderson ML, Shaughnessy EE. All hands on deck: learning to “un-specialize” in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:314-315. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3426

6. Biala D, Siegel EJ, Silver L, Schindel B, Smith KM. Deployed: pediatric residents caring for adults during COVID-19’s first wave in New York City. J Hosp Med. 2020; Published ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3527

7. Kinnear B, Kelleher M, Olson AP, Sall D, Schumacher DJ. Developing trust with early medical school graduates during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:367-369. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3463

8. Canfield GS, Schultz JS, Windham S, et al. Empiric therapies for covid-19: destined to fail by ignoring the lessons of history. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:434-436. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3469

9. Manning KD. When grief and crises intersect: perspectives of a Black physician in the time of two pandemics. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:566-567. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3481

10. Chang T. Do I have coronavirus? J Hosp Med. 2020;15:277-278. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3430

11. Guterman EL, Braunstein LZ. Preprints during the COVID-19 pandemic: public health emergencies and medical literature. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:634-636. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3491

12. Udow-Phillips M, Lantz PM. Trust in public health is essential amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:431-433. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3474

13. Hertling M. Ten tips for a crisis: lessons from a soldier. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:275-276. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3424

14. O’Glasser A [@aoglasser]. #JHMChat I also need to readily admit that part of the reason I’m a loyal, enthusiastic @JHospMedicine reader is because [Tweet]. November 16, 2020. Accessed November 28, 2020. https://twitter.com/aoglasser/status/1328529564595720192

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Email: Samir.Shah@cchmc.org; Telephone: 513-636-6222; Twitter: @SamirShahMD.

Rapid Publication, Knowledge Sharing, and Our Responsibility During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The first case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States was identified in Washington state in late January 2020. As of mid-April 2020, the number of US cases has increased to more than 800,000 with over 40,000 deaths. The limited available knowledge to guide medical decision-making combined with rapid progression of the pandemic has resulted in an urgent need to better define clinical, radiologic, and laboratory features of the disease, predictors of disease progression, predominant modes of transmission, and effective treatments. This urgency has led to a flood of manuscript submissions, which strains the scientific vetting process and leads to the spread of medical misinformation and potential for serious harm. As an example, a small observational (noncontrolled) study that used an antimalarial drug to treat COVID-19 patients was touted by several national leaders as proof of its effectiveness, despite substantial methodologic limitations.1,2 While the article has not yet been retracted, the International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, the publishing journal’s society sponsor, subsequently issued a statement that “the article does not meet the Society’s expected standard.”3

With these concerns in mind, we recognize the importance of addressing the current pandemic and identifying areas where we can advance the field responsibly in the face of limited evidence in a rapidly evolving situation. Hospitalists throughout the world are facing unprecedented leadership challenges, navigating ethical stressors, and redesigning their care systems while learning rapidly and adapting nimbly. In this issue, we share leadership strategies, explore ethical challenges and controversies, describe successful practices, and provide personal reflections from a diverse group of hospitalists and leaders. As a journal, we have intentionally avoided rapid publication of articles with substantial methodologic limitations that are unlikely to advance our knowledge of COVID-19 even though such articles may generate substantial media coverage. Different regions of the country are at different stages of the pandemic; some hospitals are experiencing high patient volumes and struggling with shortages of equipment and supplies, while others are weeks away from peak disease activity or have avoided periods of high prevalence altogether. These varied experiences offer an opportunity to share our learnings and perspectives as we wait for more definitive evidence on best management practices. As part of our commitment to our colleagues in healthcare and to the broader scientific community, all Journal of Hospital Medicine articles related to COVID-19 and published during the pandemic will be open access (ie, freely accessible).

1. Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949.

2. Baker P, Rogers K, Enrich D, Haberman M. Trump’s aggressive advocacy of malaria drug for treating coronavirus divides medical community. New York Times. April 6, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/us/politics/coronavirus-trump-malaria-drug.html. Accessed April 13, 2020.

3. International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. Statement on International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents paper. https://www.isac.world/news-and-publications/official-isac-statement. Accessed April 13, 2020.

The first case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States was identified in Washington state in late January 2020. As of mid-April 2020, the number of US cases has increased to more than 800,000 with over 40,000 deaths. The limited available knowledge to guide medical decision-making combined with rapid progression of the pandemic has resulted in an urgent need to better define clinical, radiologic, and laboratory features of the disease, predictors of disease progression, predominant modes of transmission, and effective treatments. This urgency has led to a flood of manuscript submissions, which strains the scientific vetting process and leads to the spread of medical misinformation and potential for serious harm. As an example, a small observational (noncontrolled) study that used an antimalarial drug to treat COVID-19 patients was touted by several national leaders as proof of its effectiveness, despite substantial methodologic limitations.1,2 While the article has not yet been retracted, the International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, the publishing journal’s society sponsor, subsequently issued a statement that “the article does not meet the Society’s expected standard.”3

With these concerns in mind, we recognize the importance of addressing the current pandemic and identifying areas where we can advance the field responsibly in the face of limited evidence in a rapidly evolving situation. Hospitalists throughout the world are facing unprecedented leadership challenges, navigating ethical stressors, and redesigning their care systems while learning rapidly and adapting nimbly. In this issue, we share leadership strategies, explore ethical challenges and controversies, describe successful practices, and provide personal reflections from a diverse group of hospitalists and leaders. As a journal, we have intentionally avoided rapid publication of articles with substantial methodologic limitations that are unlikely to advance our knowledge of COVID-19 even though such articles may generate substantial media coverage. Different regions of the country are at different stages of the pandemic; some hospitals are experiencing high patient volumes and struggling with shortages of equipment and supplies, while others are weeks away from peak disease activity or have avoided periods of high prevalence altogether. These varied experiences offer an opportunity to share our learnings and perspectives as we wait for more definitive evidence on best management practices. As part of our commitment to our colleagues in healthcare and to the broader scientific community, all Journal of Hospital Medicine articles related to COVID-19 and published during the pandemic will be open access (ie, freely accessible).

The first case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States was identified in Washington state in late January 2020. As of mid-April 2020, the number of US cases has increased to more than 800,000 with over 40,000 deaths. The limited available knowledge to guide medical decision-making combined with rapid progression of the pandemic has resulted in an urgent need to better define clinical, radiologic, and laboratory features of the disease, predictors of disease progression, predominant modes of transmission, and effective treatments. This urgency has led to a flood of manuscript submissions, which strains the scientific vetting process and leads to the spread of medical misinformation and potential for serious harm. As an example, a small observational (noncontrolled) study that used an antimalarial drug to treat COVID-19 patients was touted by several national leaders as proof of its effectiveness, despite substantial methodologic limitations.1,2 While the article has not yet been retracted, the International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, the publishing journal’s society sponsor, subsequently issued a statement that “the article does not meet the Society’s expected standard.”3

With these concerns in mind, we recognize the importance of addressing the current pandemic and identifying areas where we can advance the field responsibly in the face of limited evidence in a rapidly evolving situation. Hospitalists throughout the world are facing unprecedented leadership challenges, navigating ethical stressors, and redesigning their care systems while learning rapidly and adapting nimbly. In this issue, we share leadership strategies, explore ethical challenges and controversies, describe successful practices, and provide personal reflections from a diverse group of hospitalists and leaders. As a journal, we have intentionally avoided rapid publication of articles with substantial methodologic limitations that are unlikely to advance our knowledge of COVID-19 even though such articles may generate substantial media coverage. Different regions of the country are at different stages of the pandemic; some hospitals are experiencing high patient volumes and struggling with shortages of equipment and supplies, while others are weeks away from peak disease activity or have avoided periods of high prevalence altogether. These varied experiences offer an opportunity to share our learnings and perspectives as we wait for more definitive evidence on best management practices. As part of our commitment to our colleagues in healthcare and to the broader scientific community, all Journal of Hospital Medicine articles related to COVID-19 and published during the pandemic will be open access (ie, freely accessible).

1. Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949.

2. Baker P, Rogers K, Enrich D, Haberman M. Trump’s aggressive advocacy of malaria drug for treating coronavirus divides medical community. New York Times. April 6, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/us/politics/coronavirus-trump-malaria-drug.html. Accessed April 13, 2020.

3. International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. Statement on International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents paper. https://www.isac.world/news-and-publications/official-isac-statement. Accessed April 13, 2020.

1. Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949.

2. Baker P, Rogers K, Enrich D, Haberman M. Trump’s aggressive advocacy of malaria drug for treating coronavirus divides medical community. New York Times. April 6, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/us/politics/coronavirus-trump-malaria-drug.html. Accessed April 13, 2020.

3. International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. Statement on International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents paper. https://www.isac.world/news-and-publications/official-isac-statement. Accessed April 13, 2020.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine