User login

Kaposi Varicelliform Eruption of Mpox in a Peeling Sunburn

To the Editor:

The recent global mpox (monkeypox) outbreak that started in May 2022 has distinctive risk factors, clinical features, and patient attributes that can portend dissemination of infection. We report a case of Kaposi varicelliform eruption (KVE) over a peeling sunburn after mpox infection. Dermatologists should recognize cutaneous risk factors for dissemination of mpox.

A 35-year-old man who was otherwise healthy presented with a papulopustular eruption that began on the shoulders in an area that had been sunburned 24 to 48 hours earlier. He experienced fever (temperature, 38.6 °C)[101.5 °F]), chills, malaise, and the appearance of a painful penile ulcer. He reported a recent male sexual partner a week prior to the eruption during travel to eastern Asia and a subsequent male partner in the United States 5 days prior to eruption. Physical examination revealed a peeling sunburn with sharp clothing demarcation. Locations with the most notable desquamation—the superior shoulders, dorsal arms, upper chest, and ventral thighs—positively correlated with the highest density of scattered, discrete, erythematous-based pustules and pink papules, some with crusted umbilication (Figures 1 and 2). Lesions spared sun-protected locations except a punctate painful ulcer on the buccal mucosa and a tender well-demarcated ulcer with elevated borders on the ventral penile shaft. HIV antigen/antibody testing was negative; syphilis antibody testing was positive due to a prior infection 1 year earlier with titers down to 1:1. A penile ulcer swab did not detect herpes simplex virus types 1/2 DNA. Pharyngeal, penile, and rectal swabs were negative for chlamydia or gonorrhea DNA. A polymerase chain reaction assay of a pustule was positive for orthopoxvirus, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed Monkeypox virus. On day 12, a penile ulcer biopsy was nonspecific with dense mixed inflammation; immunohistochemical stains for Treponema pallidum and herpes simplex virus types 1/2 were negative. Consideration was given to starting antiviral treatment with tecovirimat, which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for smallpox caused by variola virus, through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention expanded access protocol, but the patient’s symptoms and lesions cleared quickly without intervention. The patient’s recent sexual contact in the United States later tested positive for mpox. Given that the density of our patient’s mpox lesions positively correlated with areas of peeling sunburn with rapid spread during the period of desquamation, he was diagnosed with KVE due to mpox in the setting of a peeling sunburn.

The recent mpox outbreak began in May 2022, and within 3 months there were more than 31,000 confirmed mpox cases worldwide, with more than 11,000 of those cases within the United States across 49 states and Puerto Rico.1 Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men have constituted the majority of cases. Although prior outbreaks have exhibited cases of classic mpox lesions, the current cases are clinically distinctive from classic mpox due to prevalent orogenital involvement and generalized symptoms that often are mild, nonexistent, or can occur after the cutaneous lesions.2

Although most current cases of mpox have been mildly symptomatic, several patients have been ill enough to require hospital admission, including patients with severe anogenital ulcerative lesions or bacterial superinfection.3 Antiviral treatment with tecovirimat may be warranted for patients with severe disease or those at risk of becoming severe due to immunosuppression, pregnancy/breastfeeding, complications (as determined by the provider), younger age (ie, pediatric patients), or skin barrier disruption. Dermatologists play a particularly important role in identifying cutaneous risk factors that may indicate progression of infection (eg, atopic dermatitis, severe acne, intertrigo, Darier disease). Kaposi varicelliform eruption is the phenomenon where a more typically localized vesicular infection is disseminated to areas with a defective skin barrier.2 Eczema herpeticum refers to the most common type of KVE due to herpes simplex virus, but other known etiologies of KVE include coxsackievirus A16, vaccinia virus, varicella-zoster virus, and smallpox.2 Although classic mpox previously had only the theoretical potential to lead to a secondary KVE, we expect the literature to evolve as cases spread, with one recent report of eczema monkeypoxicum in the setting of atopic dermatitis.4

At the time of publication, mpox cases have notably dropped globally due to public health interventions; however, mpox infections are ongoing in areas previously identified as nonendemic. Given the distinctive risk factors and clinical presentations of this most recent outbreak, clinicians will need to be adept at identifying not only infection but also risk for dissemination, including skin barrier disruption.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox: 2022 US map & case count. Updated February 15, 2023. Accessed February 23, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/response/2022/us-map.html

- Karray M, Kwan E, Souissi A. Kaposi varicelliform eruption. StatPearls. Updated September 12, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482432

- Girometti N, Byrne R, Bracchi M, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics of confirmed human monkeypox virus cases in individuals attending a sexual health centre in London, UK: an observational analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;S1473-3099(22)00411-X. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00411-X

- Xia J, Huang CL, Chu P, et al. Eczema monkeypoxicum: report of monkeypox transmission in patients with atopic dermatitis. JAAD Case Reports. 2022;29:95-99.

To the Editor:

The recent global mpox (monkeypox) outbreak that started in May 2022 has distinctive risk factors, clinical features, and patient attributes that can portend dissemination of infection. We report a case of Kaposi varicelliform eruption (KVE) over a peeling sunburn after mpox infection. Dermatologists should recognize cutaneous risk factors for dissemination of mpox.

A 35-year-old man who was otherwise healthy presented with a papulopustular eruption that began on the shoulders in an area that had been sunburned 24 to 48 hours earlier. He experienced fever (temperature, 38.6 °C)[101.5 °F]), chills, malaise, and the appearance of a painful penile ulcer. He reported a recent male sexual partner a week prior to the eruption during travel to eastern Asia and a subsequent male partner in the United States 5 days prior to eruption. Physical examination revealed a peeling sunburn with sharp clothing demarcation. Locations with the most notable desquamation—the superior shoulders, dorsal arms, upper chest, and ventral thighs—positively correlated with the highest density of scattered, discrete, erythematous-based pustules and pink papules, some with crusted umbilication (Figures 1 and 2). Lesions spared sun-protected locations except a punctate painful ulcer on the buccal mucosa and a tender well-demarcated ulcer with elevated borders on the ventral penile shaft. HIV antigen/antibody testing was negative; syphilis antibody testing was positive due to a prior infection 1 year earlier with titers down to 1:1. A penile ulcer swab did not detect herpes simplex virus types 1/2 DNA. Pharyngeal, penile, and rectal swabs were negative for chlamydia or gonorrhea DNA. A polymerase chain reaction assay of a pustule was positive for orthopoxvirus, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed Monkeypox virus. On day 12, a penile ulcer biopsy was nonspecific with dense mixed inflammation; immunohistochemical stains for Treponema pallidum and herpes simplex virus types 1/2 were negative. Consideration was given to starting antiviral treatment with tecovirimat, which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for smallpox caused by variola virus, through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention expanded access protocol, but the patient’s symptoms and lesions cleared quickly without intervention. The patient’s recent sexual contact in the United States later tested positive for mpox. Given that the density of our patient’s mpox lesions positively correlated with areas of peeling sunburn with rapid spread during the period of desquamation, he was diagnosed with KVE due to mpox in the setting of a peeling sunburn.

The recent mpox outbreak began in May 2022, and within 3 months there were more than 31,000 confirmed mpox cases worldwide, with more than 11,000 of those cases within the United States across 49 states and Puerto Rico.1 Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men have constituted the majority of cases. Although prior outbreaks have exhibited cases of classic mpox lesions, the current cases are clinically distinctive from classic mpox due to prevalent orogenital involvement and generalized symptoms that often are mild, nonexistent, or can occur after the cutaneous lesions.2

Although most current cases of mpox have been mildly symptomatic, several patients have been ill enough to require hospital admission, including patients with severe anogenital ulcerative lesions or bacterial superinfection.3 Antiviral treatment with tecovirimat may be warranted for patients with severe disease or those at risk of becoming severe due to immunosuppression, pregnancy/breastfeeding, complications (as determined by the provider), younger age (ie, pediatric patients), or skin barrier disruption. Dermatologists play a particularly important role in identifying cutaneous risk factors that may indicate progression of infection (eg, atopic dermatitis, severe acne, intertrigo, Darier disease). Kaposi varicelliform eruption is the phenomenon where a more typically localized vesicular infection is disseminated to areas with a defective skin barrier.2 Eczema herpeticum refers to the most common type of KVE due to herpes simplex virus, but other known etiologies of KVE include coxsackievirus A16, vaccinia virus, varicella-zoster virus, and smallpox.2 Although classic mpox previously had only the theoretical potential to lead to a secondary KVE, we expect the literature to evolve as cases spread, with one recent report of eczema monkeypoxicum in the setting of atopic dermatitis.4

At the time of publication, mpox cases have notably dropped globally due to public health interventions; however, mpox infections are ongoing in areas previously identified as nonendemic. Given the distinctive risk factors and clinical presentations of this most recent outbreak, clinicians will need to be adept at identifying not only infection but also risk for dissemination, including skin barrier disruption.

To the Editor:

The recent global mpox (monkeypox) outbreak that started in May 2022 has distinctive risk factors, clinical features, and patient attributes that can portend dissemination of infection. We report a case of Kaposi varicelliform eruption (KVE) over a peeling sunburn after mpox infection. Dermatologists should recognize cutaneous risk factors for dissemination of mpox.

A 35-year-old man who was otherwise healthy presented with a papulopustular eruption that began on the shoulders in an area that had been sunburned 24 to 48 hours earlier. He experienced fever (temperature, 38.6 °C)[101.5 °F]), chills, malaise, and the appearance of a painful penile ulcer. He reported a recent male sexual partner a week prior to the eruption during travel to eastern Asia and a subsequent male partner in the United States 5 days prior to eruption. Physical examination revealed a peeling sunburn with sharp clothing demarcation. Locations with the most notable desquamation—the superior shoulders, dorsal arms, upper chest, and ventral thighs—positively correlated with the highest density of scattered, discrete, erythematous-based pustules and pink papules, some with crusted umbilication (Figures 1 and 2). Lesions spared sun-protected locations except a punctate painful ulcer on the buccal mucosa and a tender well-demarcated ulcer with elevated borders on the ventral penile shaft. HIV antigen/antibody testing was negative; syphilis antibody testing was positive due to a prior infection 1 year earlier with titers down to 1:1. A penile ulcer swab did not detect herpes simplex virus types 1/2 DNA. Pharyngeal, penile, and rectal swabs were negative for chlamydia or gonorrhea DNA. A polymerase chain reaction assay of a pustule was positive for orthopoxvirus, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed Monkeypox virus. On day 12, a penile ulcer biopsy was nonspecific with dense mixed inflammation; immunohistochemical stains for Treponema pallidum and herpes simplex virus types 1/2 were negative. Consideration was given to starting antiviral treatment with tecovirimat, which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for smallpox caused by variola virus, through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention expanded access protocol, but the patient’s symptoms and lesions cleared quickly without intervention. The patient’s recent sexual contact in the United States later tested positive for mpox. Given that the density of our patient’s mpox lesions positively correlated with areas of peeling sunburn with rapid spread during the period of desquamation, he was diagnosed with KVE due to mpox in the setting of a peeling sunburn.

The recent mpox outbreak began in May 2022, and within 3 months there were more than 31,000 confirmed mpox cases worldwide, with more than 11,000 of those cases within the United States across 49 states and Puerto Rico.1 Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men have constituted the majority of cases. Although prior outbreaks have exhibited cases of classic mpox lesions, the current cases are clinically distinctive from classic mpox due to prevalent orogenital involvement and generalized symptoms that often are mild, nonexistent, or can occur after the cutaneous lesions.2

Although most current cases of mpox have been mildly symptomatic, several patients have been ill enough to require hospital admission, including patients with severe anogenital ulcerative lesions or bacterial superinfection.3 Antiviral treatment with tecovirimat may be warranted for patients with severe disease or those at risk of becoming severe due to immunosuppression, pregnancy/breastfeeding, complications (as determined by the provider), younger age (ie, pediatric patients), or skin barrier disruption. Dermatologists play a particularly important role in identifying cutaneous risk factors that may indicate progression of infection (eg, atopic dermatitis, severe acne, intertrigo, Darier disease). Kaposi varicelliform eruption is the phenomenon where a more typically localized vesicular infection is disseminated to areas with a defective skin barrier.2 Eczema herpeticum refers to the most common type of KVE due to herpes simplex virus, but other known etiologies of KVE include coxsackievirus A16, vaccinia virus, varicella-zoster virus, and smallpox.2 Although classic mpox previously had only the theoretical potential to lead to a secondary KVE, we expect the literature to evolve as cases spread, with one recent report of eczema monkeypoxicum in the setting of atopic dermatitis.4

At the time of publication, mpox cases have notably dropped globally due to public health interventions; however, mpox infections are ongoing in areas previously identified as nonendemic. Given the distinctive risk factors and clinical presentations of this most recent outbreak, clinicians will need to be adept at identifying not only infection but also risk for dissemination, including skin barrier disruption.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox: 2022 US map & case count. Updated February 15, 2023. Accessed February 23, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/response/2022/us-map.html

- Karray M, Kwan E, Souissi A. Kaposi varicelliform eruption. StatPearls. Updated September 12, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482432

- Girometti N, Byrne R, Bracchi M, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics of confirmed human monkeypox virus cases in individuals attending a sexual health centre in London, UK: an observational analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;S1473-3099(22)00411-X. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00411-X

- Xia J, Huang CL, Chu P, et al. Eczema monkeypoxicum: report of monkeypox transmission in patients with atopic dermatitis. JAAD Case Reports. 2022;29:95-99.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox: 2022 US map & case count. Updated February 15, 2023. Accessed February 23, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/response/2022/us-map.html

- Karray M, Kwan E, Souissi A. Kaposi varicelliform eruption. StatPearls. Updated September 12, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482432

- Girometti N, Byrne R, Bracchi M, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics of confirmed human monkeypox virus cases in individuals attending a sexual health centre in London, UK: an observational analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;S1473-3099(22)00411-X. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00411-X

- Xia J, Huang CL, Chu P, et al. Eczema monkeypoxicum: report of monkeypox transmission in patients with atopic dermatitis. JAAD Case Reports. 2022;29:95-99.

Practice Points

- Desquamation can be associated with dissemination and higher severity course in the setting of mpox (monkeypox) viral infection.

- Antiviral treatment with tecovirimat is warranted in those with severe mpox infection or those at risk of severe infection including skin barrier disruption.

- Kaposi varicelliform–like eruptions can happen in the setting of barrier disruption from peeling sunburns, atopic dermatitis, severe acne, and other dermatologic conditions.

Painful Papules on the Arms

The Diagnosis: Piloleiomyoma

Leiomyoma cutis, also known as cutaneous leiomyoma, is a benign smooth muscle tumor first described in 1854.1 Cutaneous leiomyoma is comprised of 3 distinct types that depend on the origin of smooth muscle tumor: piloleiomyoma (arrector pili muscle), angioleiomyoma (tunica media of arteries/veins), and genital leiomyoma (dartos muscle of the scrotum and labia majora, erectile muscle of nipple).2 It affects both sexes equally, though some reports have noted an increased prevalence in females. Piloleiomyomas commonly present on the extensor surfaces of the extremities (solitary) and trunk (multiple).1 Tumors most often present as firm flesh-colored or pink-brown papulonodules. They can be linear, dermatomal, segmental, or diffuse, and often are painful. Clinical differential diagnosis for painful skin tumors is aided by the acronym "BLEND AN EGG": blue rubber bleb nevus, leiomyoma, eccrine spiradenoma, neuroma, dermatofibroma, angiolipoma, neurilemmoma, endometrioma, glomangioma, and granular cell tumor.3 For isolated lesions, surgical excision is the treatment of choice. For numerous lesions in which excision would not be feasible, intralesional corticosteroids, medications (eg, calcium channel blockers, alpha blockers, nitroglycerin), and botulinum toxin have been used for pain relief.4

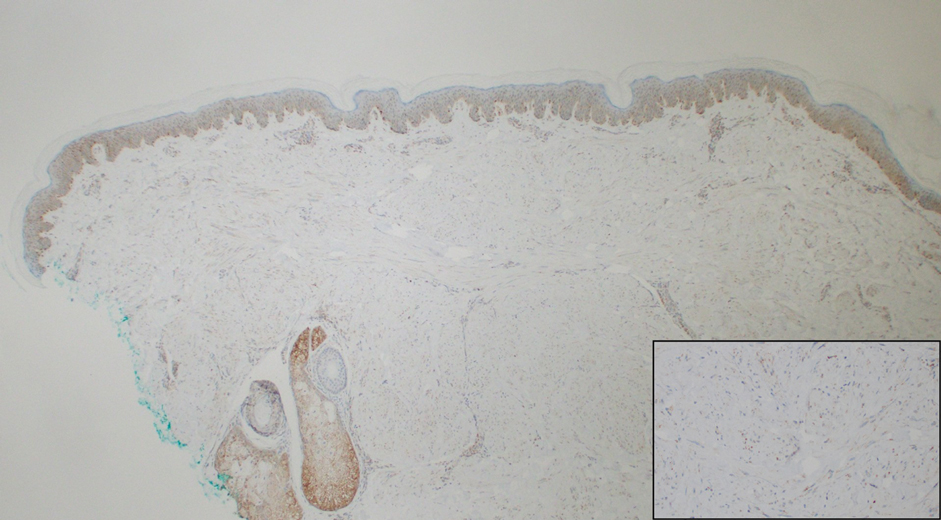

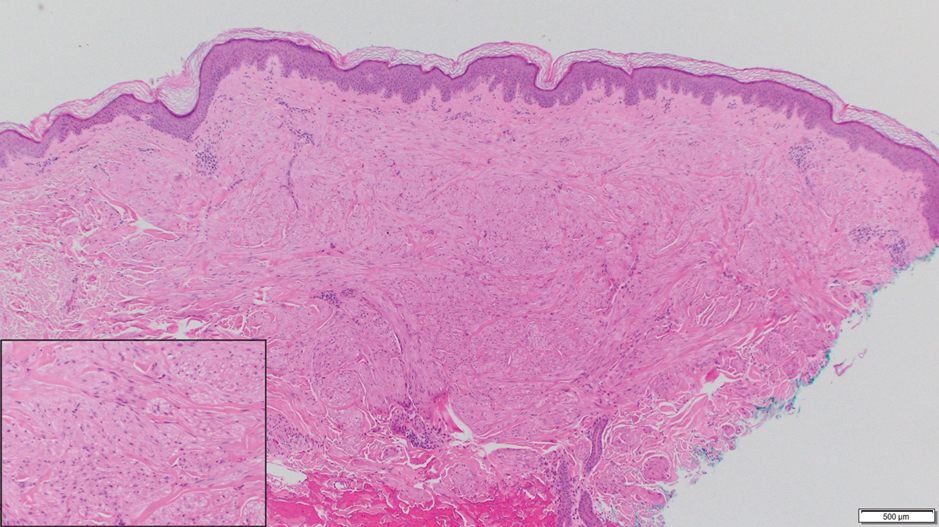

Notably, multiple cutaneous leiomyomas can be seen in association with uterine leiomyomas in Reed syndrome due to an autosomal-dominant or de novo mutation in the fumarate hydratase gene, FH. Reed syndrome is associated with a lifetime risk for renal cell carcinoma (hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer) in 15% of cases with FH mutations.5 In our patient, both immunohistochemical staining and blood testing for FH were performed. Immunohistochemistry revealed notably diminished staining with only weak patchy granular cytoplasmic staining present (Figure 1). Genetic testing revealed heterozygosity for a pathogenic variant of the FH gene, consistent with a diagnosis of Reed syndrome.

Histologically, the differential diagnosis includes other spindle cell tumors, such as dermatofibroma, neurofibroma, and dermatomyofibroma. The histologic appearance varies depending on the type, with piloleiomyoma typically located within the reticular dermis with possible subcutaneous extension. Fascicles of eosinophilic smooth muscle cells in an interlacing arrangement often ramify between neighboring dermal collagen; these smooth muscle cells contain cigar-shaped, blunt-ended nuclei with a perinuclear clear vacuole. Marked epidermal hyperplasia is possible.6 A close association with a nearby hair follicle frequently is noted. Although differentiated smooth muscle cells usually are evident on hematoxylin and eosin, positive staining for smooth muscle actin (SMA) and desmin can aid in diagnosis.7 Immunohistochemical staining for FH has proven to be highly specific (97.6%) with moderate sensitivity (70.0%).8 Angioleiomyomas appear as well-demarcated dermal to subcutaneous tumors composed of smooth muscle cells surrounding thick-walled vaculature.9 Scrotal and vulvar leiomyomas are composed of eosinophilic spindle cells, though vulvar leiomyomas have shown epithelioid differentiation.10 Nipple leiomyomas appear similar to piloleiomyomas on histology with interlacing smooth muscle fiber bundles.

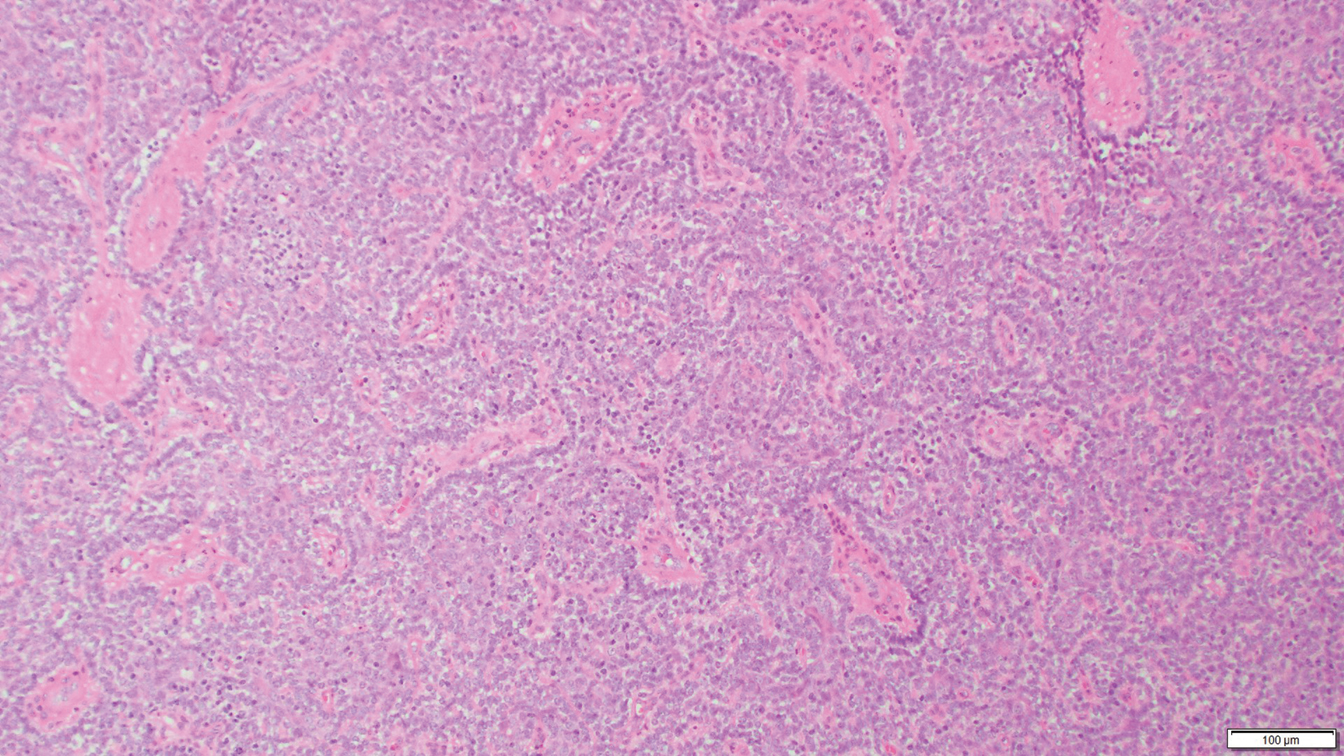

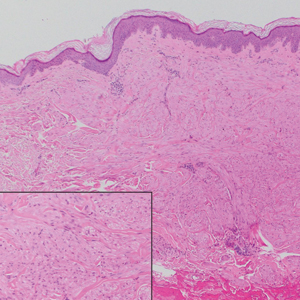

Eccrine spiradenoma is a relatively uncommon adnexal tumor derived from eccrine sweat glands. It most often presents as a small, painful or tender, intradermal nodule (or rarely as nodules) on the head or ventral trunk.11 There is no sexual predilection. It affects adults at any age but most often from 15 to 35 years. Although rare, malignant transformation is possible. Histologically, eccrine spiradenomas appear as a well-demarcated dermal tumor composed of bland basaloid cells with minimal cytoplasm, often with numerous admixed lymphocytes and variably prominent vasculature (Figure 2). Eosinophilic basement membrane material can be seen within or surrounding the nodules of tumor cells. Multiple spiradenomas can occur in the setting of Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, which is an autosomal-dominant disorder due to an inherited mutation in the CYLD gene. Spiradenomas are benign neoplasms, and surgical excision with clear margins is the treatment of choice.12

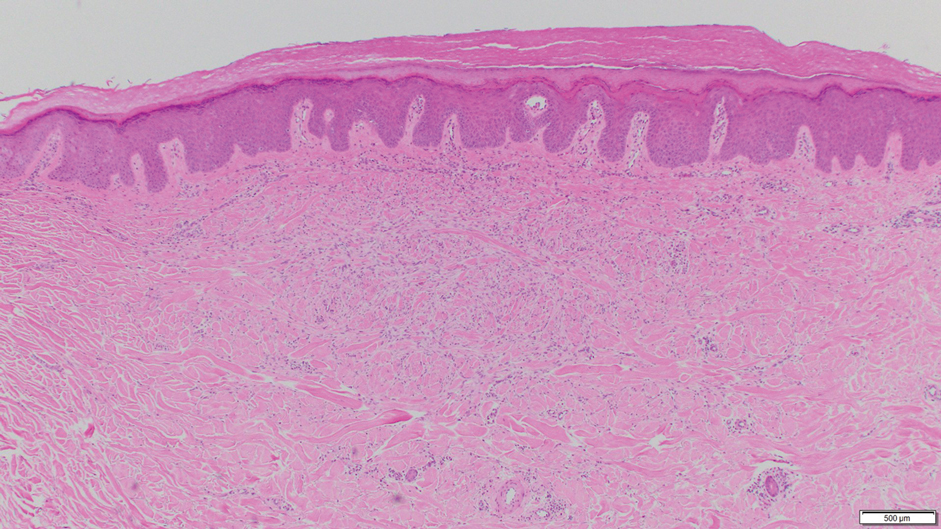

Dermatofibroma, also known as cutaneous benign fibrous histiocytoma, is a firm, flesh-colored papule or nodule that most often presents on the lower extremities. It typically is seen in women aged 20 to 40 years.13 The etiology is uncertain, and dermatofibromas often spontaneously develop, though there are inconsistent reports of development with local trauma including insect bites and puncture wounds. The dimple sign refers to skin dimpling with lateral pressure.13 Most commonly, dermatofibromas consist of a dermal proliferation of bland fibroblastic cells with entrapment of dermal collagen bundles at the periphery of the tumors (Figure 3). The fibroblastic cells often are paler and less eosinophilic than smooth muscle cells seen in cutaneous leiomyomas, with tapered nuclei that lack a perinuclear vacuole. Admixed histocytes and other inflammatory cells often are present. Overlying epidermal hyperplasia and/or hyperpigmentation also may be present. Numerous histologic variants have been described, including cellular, epithelioid, aneurysmal, atypical, and hemosiderotic types.14 Immunohistochemical stains may show patchy positive staining for SMA, but h-caldesmon and desmin typically are negative.

Neurofibroma is a tumor derived from neuromesenchymal tissue with nerve axons. They form through neuromesenchyme (eg, Schwann cells, mast cells, perineural cells, endoneural fibroblast) proliferation. Solitary neurofibromas occur most commonly in adults and have no gender predilection. The most common presentation is an asymptomatic, solitary, soft, flesh-colored papulonodule.15 Clinical variants include pigmented, diffuse, and plexiform, with plexiform neurofibromas almost always being consistent with a diagnosis of neurofibromatosis type 1. Histologically, neurofibromas present as dermal or subcutaneous nodules composed of randomly arranged spindle cells with wavy tapered nuclei within a loose collagenous stroma (Figure 4).16 The spindle cells in neurofibromas will stain positively for S-100 protein and SOX-10 and negatively for SMA and desmin.

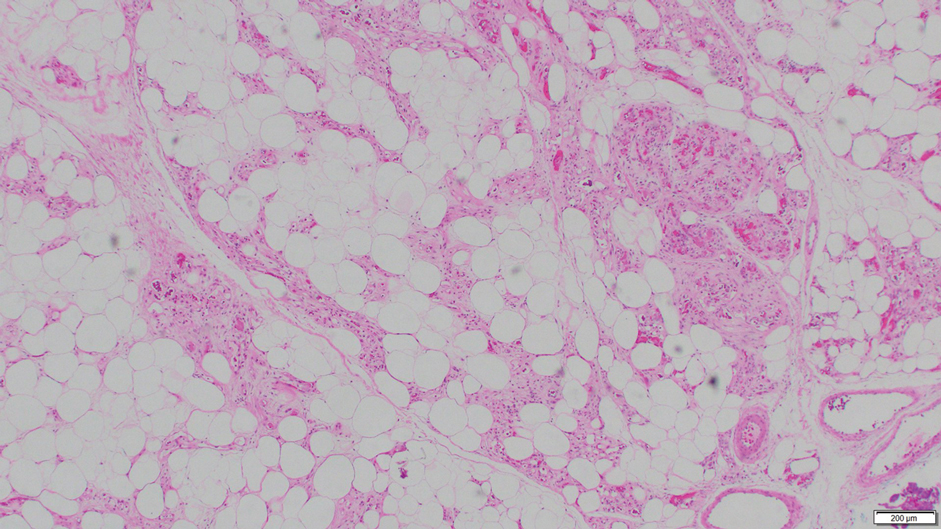

Angiolipoma is a benign tumor composed of adipocytes that also contains vasculature.17 The majority of cases are of unknown etiology, though familial cases have been described. They typically present as multiple painful or tender (differentiating from lipomas) subcutaneous swellings over the forearms in individuals aged 20 to 30 years.18 On histopathology, angiolipomas appear as well-circumscribed subcutaneous tumors containing mature adipocytes intermixed with small capillary vessels, some of which contain luminal fibrin thrombi (Figure 5).

- Malik K, Patel P, Chen J, et al. Leiomyoma cutis: a focused review on presentation, management, and association with malignancy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:35-46.

- Malhotra P, Walia H, Singh A, et al. Leiomyoma cutis: a clinicopathological series of 37 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:337-341.

- Delfino S, Toto V, Brunetti B, et al. Recurrent atypical eccrine spiradenoma of the forehead. In Vivo. 2008;22:821-823.

- Onder M, Adis¸en E. A new indication of botulinum toxin: leiomyoma-related pain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:325-328.

- Menko FH, Maher ER, Schmidt LS, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC): renal cancer risk, surveillance and treatment. Fam Cancer. 2014;13:637-644.

- Raj S, Calonje E, Kraus M, et al. Cutaneous pilar leiomyoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 53 lesions in 45 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:2-9.

- Choi JH, Ro JY. Cutaneous spindle cell neoplasms: pattern-based diagnostic approach. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:958-972.

- Carter CS, Skala SL, Chinnaiyan AM, et al. Immunohistochemical characterization of fumarate hydratase (FH) and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) in cutaneous leiomyomas for detection of familial cancer syndromes. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:801-809.

- Kanitakis J. Angioleiomyoma of the auricle: an unusual tumor on a rare location. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2017;2017:1-3.

- Tavassoli FA, Norris HJ. Smooth muscle tumors of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53:213-217.

- Phukan J, Sinha A, Pal S. Fine needle aspiration cytology of eccrine spiradenoma of back: report of a rare case. J Lab Physicians. 2014;6:130.

- Zheng Y, Tian Q, Wang J, et al. Differential diagnosis of eccrine spiradenoma: a case report. Exp Ther Med. 2014;8:1097-1101.

- Bandyopadhyay MR, Besra M, Dutta S, et al. Dermatofibroma: atypical presentations. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:121.

- Commons JD, Parish L, Yazdanian S, et al. Dermatofibroma: a curious tumor. Skinmed. 2012;10:268-270.

- Lee YB, Lee JI, Park HJ, et al. Solitary neurofibromas: does an uncommon site exist? Ann Dermatol. 2012;24:101-102.

- Ortonne N, Wolkenstein P, Blakeley JO, et al. Cutaneous neurofibromas: current clinical and pathologic issues. Neurology. 2018;91:S5-S13.

- Howard WR. Angiolipoma. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:924.

- Ghosh S, Haldar BA. Multiple angiolipomas. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1990;56:143-144.

The Diagnosis: Piloleiomyoma

Leiomyoma cutis, also known as cutaneous leiomyoma, is a benign smooth muscle tumor first described in 1854.1 Cutaneous leiomyoma is comprised of 3 distinct types that depend on the origin of smooth muscle tumor: piloleiomyoma (arrector pili muscle), angioleiomyoma (tunica media of arteries/veins), and genital leiomyoma (dartos muscle of the scrotum and labia majora, erectile muscle of nipple).2 It affects both sexes equally, though some reports have noted an increased prevalence in females. Piloleiomyomas commonly present on the extensor surfaces of the extremities (solitary) and trunk (multiple).1 Tumors most often present as firm flesh-colored or pink-brown papulonodules. They can be linear, dermatomal, segmental, or diffuse, and often are painful. Clinical differential diagnosis for painful skin tumors is aided by the acronym "BLEND AN EGG": blue rubber bleb nevus, leiomyoma, eccrine spiradenoma, neuroma, dermatofibroma, angiolipoma, neurilemmoma, endometrioma, glomangioma, and granular cell tumor.3 For isolated lesions, surgical excision is the treatment of choice. For numerous lesions in which excision would not be feasible, intralesional corticosteroids, medications (eg, calcium channel blockers, alpha blockers, nitroglycerin), and botulinum toxin have been used for pain relief.4

Notably, multiple cutaneous leiomyomas can be seen in association with uterine leiomyomas in Reed syndrome due to an autosomal-dominant or de novo mutation in the fumarate hydratase gene, FH. Reed syndrome is associated with a lifetime risk for renal cell carcinoma (hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer) in 15% of cases with FH mutations.5 In our patient, both immunohistochemical staining and blood testing for FH were performed. Immunohistochemistry revealed notably diminished staining with only weak patchy granular cytoplasmic staining present (Figure 1). Genetic testing revealed heterozygosity for a pathogenic variant of the FH gene, consistent with a diagnosis of Reed syndrome.

Histologically, the differential diagnosis includes other spindle cell tumors, such as dermatofibroma, neurofibroma, and dermatomyofibroma. The histologic appearance varies depending on the type, with piloleiomyoma typically located within the reticular dermis with possible subcutaneous extension. Fascicles of eosinophilic smooth muscle cells in an interlacing arrangement often ramify between neighboring dermal collagen; these smooth muscle cells contain cigar-shaped, blunt-ended nuclei with a perinuclear clear vacuole. Marked epidermal hyperplasia is possible.6 A close association with a nearby hair follicle frequently is noted. Although differentiated smooth muscle cells usually are evident on hematoxylin and eosin, positive staining for smooth muscle actin (SMA) and desmin can aid in diagnosis.7 Immunohistochemical staining for FH has proven to be highly specific (97.6%) with moderate sensitivity (70.0%).8 Angioleiomyomas appear as well-demarcated dermal to subcutaneous tumors composed of smooth muscle cells surrounding thick-walled vaculature.9 Scrotal and vulvar leiomyomas are composed of eosinophilic spindle cells, though vulvar leiomyomas have shown epithelioid differentiation.10 Nipple leiomyomas appear similar to piloleiomyomas on histology with interlacing smooth muscle fiber bundles.

Eccrine spiradenoma is a relatively uncommon adnexal tumor derived from eccrine sweat glands. It most often presents as a small, painful or tender, intradermal nodule (or rarely as nodules) on the head or ventral trunk.11 There is no sexual predilection. It affects adults at any age but most often from 15 to 35 years. Although rare, malignant transformation is possible. Histologically, eccrine spiradenomas appear as a well-demarcated dermal tumor composed of bland basaloid cells with minimal cytoplasm, often with numerous admixed lymphocytes and variably prominent vasculature (Figure 2). Eosinophilic basement membrane material can be seen within or surrounding the nodules of tumor cells. Multiple spiradenomas can occur in the setting of Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, which is an autosomal-dominant disorder due to an inherited mutation in the CYLD gene. Spiradenomas are benign neoplasms, and surgical excision with clear margins is the treatment of choice.12

Dermatofibroma, also known as cutaneous benign fibrous histiocytoma, is a firm, flesh-colored papule or nodule that most often presents on the lower extremities. It typically is seen in women aged 20 to 40 years.13 The etiology is uncertain, and dermatofibromas often spontaneously develop, though there are inconsistent reports of development with local trauma including insect bites and puncture wounds. The dimple sign refers to skin dimpling with lateral pressure.13 Most commonly, dermatofibromas consist of a dermal proliferation of bland fibroblastic cells with entrapment of dermal collagen bundles at the periphery of the tumors (Figure 3). The fibroblastic cells often are paler and less eosinophilic than smooth muscle cells seen in cutaneous leiomyomas, with tapered nuclei that lack a perinuclear vacuole. Admixed histocytes and other inflammatory cells often are present. Overlying epidermal hyperplasia and/or hyperpigmentation also may be present. Numerous histologic variants have been described, including cellular, epithelioid, aneurysmal, atypical, and hemosiderotic types.14 Immunohistochemical stains may show patchy positive staining for SMA, but h-caldesmon and desmin typically are negative.

Neurofibroma is a tumor derived from neuromesenchymal tissue with nerve axons. They form through neuromesenchyme (eg, Schwann cells, mast cells, perineural cells, endoneural fibroblast) proliferation. Solitary neurofibromas occur most commonly in adults and have no gender predilection. The most common presentation is an asymptomatic, solitary, soft, flesh-colored papulonodule.15 Clinical variants include pigmented, diffuse, and plexiform, with plexiform neurofibromas almost always being consistent with a diagnosis of neurofibromatosis type 1. Histologically, neurofibromas present as dermal or subcutaneous nodules composed of randomly arranged spindle cells with wavy tapered nuclei within a loose collagenous stroma (Figure 4).16 The spindle cells in neurofibromas will stain positively for S-100 protein and SOX-10 and negatively for SMA and desmin.

Angiolipoma is a benign tumor composed of adipocytes that also contains vasculature.17 The majority of cases are of unknown etiology, though familial cases have been described. They typically present as multiple painful or tender (differentiating from lipomas) subcutaneous swellings over the forearms in individuals aged 20 to 30 years.18 On histopathology, angiolipomas appear as well-circumscribed subcutaneous tumors containing mature adipocytes intermixed with small capillary vessels, some of which contain luminal fibrin thrombi (Figure 5).

The Diagnosis: Piloleiomyoma

Leiomyoma cutis, also known as cutaneous leiomyoma, is a benign smooth muscle tumor first described in 1854.1 Cutaneous leiomyoma is comprised of 3 distinct types that depend on the origin of smooth muscle tumor: piloleiomyoma (arrector pili muscle), angioleiomyoma (tunica media of arteries/veins), and genital leiomyoma (dartos muscle of the scrotum and labia majora, erectile muscle of nipple).2 It affects both sexes equally, though some reports have noted an increased prevalence in females. Piloleiomyomas commonly present on the extensor surfaces of the extremities (solitary) and trunk (multiple).1 Tumors most often present as firm flesh-colored or pink-brown papulonodules. They can be linear, dermatomal, segmental, or diffuse, and often are painful. Clinical differential diagnosis for painful skin tumors is aided by the acronym "BLEND AN EGG": blue rubber bleb nevus, leiomyoma, eccrine spiradenoma, neuroma, dermatofibroma, angiolipoma, neurilemmoma, endometrioma, glomangioma, and granular cell tumor.3 For isolated lesions, surgical excision is the treatment of choice. For numerous lesions in which excision would not be feasible, intralesional corticosteroids, medications (eg, calcium channel blockers, alpha blockers, nitroglycerin), and botulinum toxin have been used for pain relief.4

Notably, multiple cutaneous leiomyomas can be seen in association with uterine leiomyomas in Reed syndrome due to an autosomal-dominant or de novo mutation in the fumarate hydratase gene, FH. Reed syndrome is associated with a lifetime risk for renal cell carcinoma (hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer) in 15% of cases with FH mutations.5 In our patient, both immunohistochemical staining and blood testing for FH were performed. Immunohistochemistry revealed notably diminished staining with only weak patchy granular cytoplasmic staining present (Figure 1). Genetic testing revealed heterozygosity for a pathogenic variant of the FH gene, consistent with a diagnosis of Reed syndrome.

Histologically, the differential diagnosis includes other spindle cell tumors, such as dermatofibroma, neurofibroma, and dermatomyofibroma. The histologic appearance varies depending on the type, with piloleiomyoma typically located within the reticular dermis with possible subcutaneous extension. Fascicles of eosinophilic smooth muscle cells in an interlacing arrangement often ramify between neighboring dermal collagen; these smooth muscle cells contain cigar-shaped, blunt-ended nuclei with a perinuclear clear vacuole. Marked epidermal hyperplasia is possible.6 A close association with a nearby hair follicle frequently is noted. Although differentiated smooth muscle cells usually are evident on hematoxylin and eosin, positive staining for smooth muscle actin (SMA) and desmin can aid in diagnosis.7 Immunohistochemical staining for FH has proven to be highly specific (97.6%) with moderate sensitivity (70.0%).8 Angioleiomyomas appear as well-demarcated dermal to subcutaneous tumors composed of smooth muscle cells surrounding thick-walled vaculature.9 Scrotal and vulvar leiomyomas are composed of eosinophilic spindle cells, though vulvar leiomyomas have shown epithelioid differentiation.10 Nipple leiomyomas appear similar to piloleiomyomas on histology with interlacing smooth muscle fiber bundles.

Eccrine spiradenoma is a relatively uncommon adnexal tumor derived from eccrine sweat glands. It most often presents as a small, painful or tender, intradermal nodule (or rarely as nodules) on the head or ventral trunk.11 There is no sexual predilection. It affects adults at any age but most often from 15 to 35 years. Although rare, malignant transformation is possible. Histologically, eccrine spiradenomas appear as a well-demarcated dermal tumor composed of bland basaloid cells with minimal cytoplasm, often with numerous admixed lymphocytes and variably prominent vasculature (Figure 2). Eosinophilic basement membrane material can be seen within or surrounding the nodules of tumor cells. Multiple spiradenomas can occur in the setting of Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, which is an autosomal-dominant disorder due to an inherited mutation in the CYLD gene. Spiradenomas are benign neoplasms, and surgical excision with clear margins is the treatment of choice.12

Dermatofibroma, also known as cutaneous benign fibrous histiocytoma, is a firm, flesh-colored papule or nodule that most often presents on the lower extremities. It typically is seen in women aged 20 to 40 years.13 The etiology is uncertain, and dermatofibromas often spontaneously develop, though there are inconsistent reports of development with local trauma including insect bites and puncture wounds. The dimple sign refers to skin dimpling with lateral pressure.13 Most commonly, dermatofibromas consist of a dermal proliferation of bland fibroblastic cells with entrapment of dermal collagen bundles at the periphery of the tumors (Figure 3). The fibroblastic cells often are paler and less eosinophilic than smooth muscle cells seen in cutaneous leiomyomas, with tapered nuclei that lack a perinuclear vacuole. Admixed histocytes and other inflammatory cells often are present. Overlying epidermal hyperplasia and/or hyperpigmentation also may be present. Numerous histologic variants have been described, including cellular, epithelioid, aneurysmal, atypical, and hemosiderotic types.14 Immunohistochemical stains may show patchy positive staining for SMA, but h-caldesmon and desmin typically are negative.

Neurofibroma is a tumor derived from neuromesenchymal tissue with nerve axons. They form through neuromesenchyme (eg, Schwann cells, mast cells, perineural cells, endoneural fibroblast) proliferation. Solitary neurofibromas occur most commonly in adults and have no gender predilection. The most common presentation is an asymptomatic, solitary, soft, flesh-colored papulonodule.15 Clinical variants include pigmented, diffuse, and plexiform, with plexiform neurofibromas almost always being consistent with a diagnosis of neurofibromatosis type 1. Histologically, neurofibromas present as dermal or subcutaneous nodules composed of randomly arranged spindle cells with wavy tapered nuclei within a loose collagenous stroma (Figure 4).16 The spindle cells in neurofibromas will stain positively for S-100 protein and SOX-10 and negatively for SMA and desmin.

Angiolipoma is a benign tumor composed of adipocytes that also contains vasculature.17 The majority of cases are of unknown etiology, though familial cases have been described. They typically present as multiple painful or tender (differentiating from lipomas) subcutaneous swellings over the forearms in individuals aged 20 to 30 years.18 On histopathology, angiolipomas appear as well-circumscribed subcutaneous tumors containing mature adipocytes intermixed with small capillary vessels, some of which contain luminal fibrin thrombi (Figure 5).

- Malik K, Patel P, Chen J, et al. Leiomyoma cutis: a focused review on presentation, management, and association with malignancy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:35-46.

- Malhotra P, Walia H, Singh A, et al. Leiomyoma cutis: a clinicopathological series of 37 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:337-341.

- Delfino S, Toto V, Brunetti B, et al. Recurrent atypical eccrine spiradenoma of the forehead. In Vivo. 2008;22:821-823.

- Onder M, Adis¸en E. A new indication of botulinum toxin: leiomyoma-related pain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:325-328.

- Menko FH, Maher ER, Schmidt LS, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC): renal cancer risk, surveillance and treatment. Fam Cancer. 2014;13:637-644.

- Raj S, Calonje E, Kraus M, et al. Cutaneous pilar leiomyoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 53 lesions in 45 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:2-9.

- Choi JH, Ro JY. Cutaneous spindle cell neoplasms: pattern-based diagnostic approach. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:958-972.

- Carter CS, Skala SL, Chinnaiyan AM, et al. Immunohistochemical characterization of fumarate hydratase (FH) and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) in cutaneous leiomyomas for detection of familial cancer syndromes. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:801-809.

- Kanitakis J. Angioleiomyoma of the auricle: an unusual tumor on a rare location. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2017;2017:1-3.

- Tavassoli FA, Norris HJ. Smooth muscle tumors of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53:213-217.

- Phukan J, Sinha A, Pal S. Fine needle aspiration cytology of eccrine spiradenoma of back: report of a rare case. J Lab Physicians. 2014;6:130.

- Zheng Y, Tian Q, Wang J, et al. Differential diagnosis of eccrine spiradenoma: a case report. Exp Ther Med. 2014;8:1097-1101.

- Bandyopadhyay MR, Besra M, Dutta S, et al. Dermatofibroma: atypical presentations. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:121.

- Commons JD, Parish L, Yazdanian S, et al. Dermatofibroma: a curious tumor. Skinmed. 2012;10:268-270.

- Lee YB, Lee JI, Park HJ, et al. Solitary neurofibromas: does an uncommon site exist? Ann Dermatol. 2012;24:101-102.

- Ortonne N, Wolkenstein P, Blakeley JO, et al. Cutaneous neurofibromas: current clinical and pathologic issues. Neurology. 2018;91:S5-S13.

- Howard WR. Angiolipoma. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:924.

- Ghosh S, Haldar BA. Multiple angiolipomas. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1990;56:143-144.

- Malik K, Patel P, Chen J, et al. Leiomyoma cutis: a focused review on presentation, management, and association with malignancy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:35-46.

- Malhotra P, Walia H, Singh A, et al. Leiomyoma cutis: a clinicopathological series of 37 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:337-341.

- Delfino S, Toto V, Brunetti B, et al. Recurrent atypical eccrine spiradenoma of the forehead. In Vivo. 2008;22:821-823.

- Onder M, Adis¸en E. A new indication of botulinum toxin: leiomyoma-related pain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:325-328.

- Menko FH, Maher ER, Schmidt LS, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC): renal cancer risk, surveillance and treatment. Fam Cancer. 2014;13:637-644.

- Raj S, Calonje E, Kraus M, et al. Cutaneous pilar leiomyoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 53 lesions in 45 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:2-9.

- Choi JH, Ro JY. Cutaneous spindle cell neoplasms: pattern-based diagnostic approach. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:958-972.

- Carter CS, Skala SL, Chinnaiyan AM, et al. Immunohistochemical characterization of fumarate hydratase (FH) and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) in cutaneous leiomyomas for detection of familial cancer syndromes. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:801-809.

- Kanitakis J. Angioleiomyoma of the auricle: an unusual tumor on a rare location. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2017;2017:1-3.

- Tavassoli FA, Norris HJ. Smooth muscle tumors of the vulva. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;53:213-217.

- Phukan J, Sinha A, Pal S. Fine needle aspiration cytology of eccrine spiradenoma of back: report of a rare case. J Lab Physicians. 2014;6:130.

- Zheng Y, Tian Q, Wang J, et al. Differential diagnosis of eccrine spiradenoma: a case report. Exp Ther Med. 2014;8:1097-1101.

- Bandyopadhyay MR, Besra M, Dutta S, et al. Dermatofibroma: atypical presentations. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:121.

- Commons JD, Parish L, Yazdanian S, et al. Dermatofibroma: a curious tumor. Skinmed. 2012;10:268-270.

- Lee YB, Lee JI, Park HJ, et al. Solitary neurofibromas: does an uncommon site exist? Ann Dermatol. 2012;24:101-102.

- Ortonne N, Wolkenstein P, Blakeley JO, et al. Cutaneous neurofibromas: current clinical and pathologic issues. Neurology. 2018;91:S5-S13.

- Howard WR. Angiolipoma. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:924.

- Ghosh S, Haldar BA. Multiple angiolipomas. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1990;56:143-144.

A 36-year-old woman presented with multiple new-onset, firm, tender, subcutaneous papules and nodules involving the upper arms and shoulders.