User login

Field Cancerization With Multiple Keratoacanthomas Successfully Treated With Topical and Intralesional 5-Fluorouracil

To the Editor:

The concept of field cancerization has been well described since its initial proposal by Slaughter et al1 in 1953. It describes a field of genetically altered cells where multiple clonally related neoplasms can develop.2,3 Treatment of patients with multiple neoplasms within an area of field cancerization can be especially challenging. We report a patient with field cancerization who had multiple squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) and keratoacanthomas (KAs) that arose within the field.

A 78-year-old man initially presented with a papule on the right forearm of 3 months’ duration. He had a medical history of cutaneous SCC, myocardial infarction, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, gout, and diverticulosis. He was not taking any chronic immunosuppressants that may have predisposed him to the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer. The papule was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated invasive SCC. A month later it was excised with clear margins.

Approximately 5 weeks after the excision, he returned with an enlarging lesion on the right forearm just medial to the excision site. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. Two months later the lesion was excised with clear margins. Four weeks later he returned with a new lesion adjacent to the medial aspect of the prior excision. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. Four weeks later the lesion was excised with clear margins.

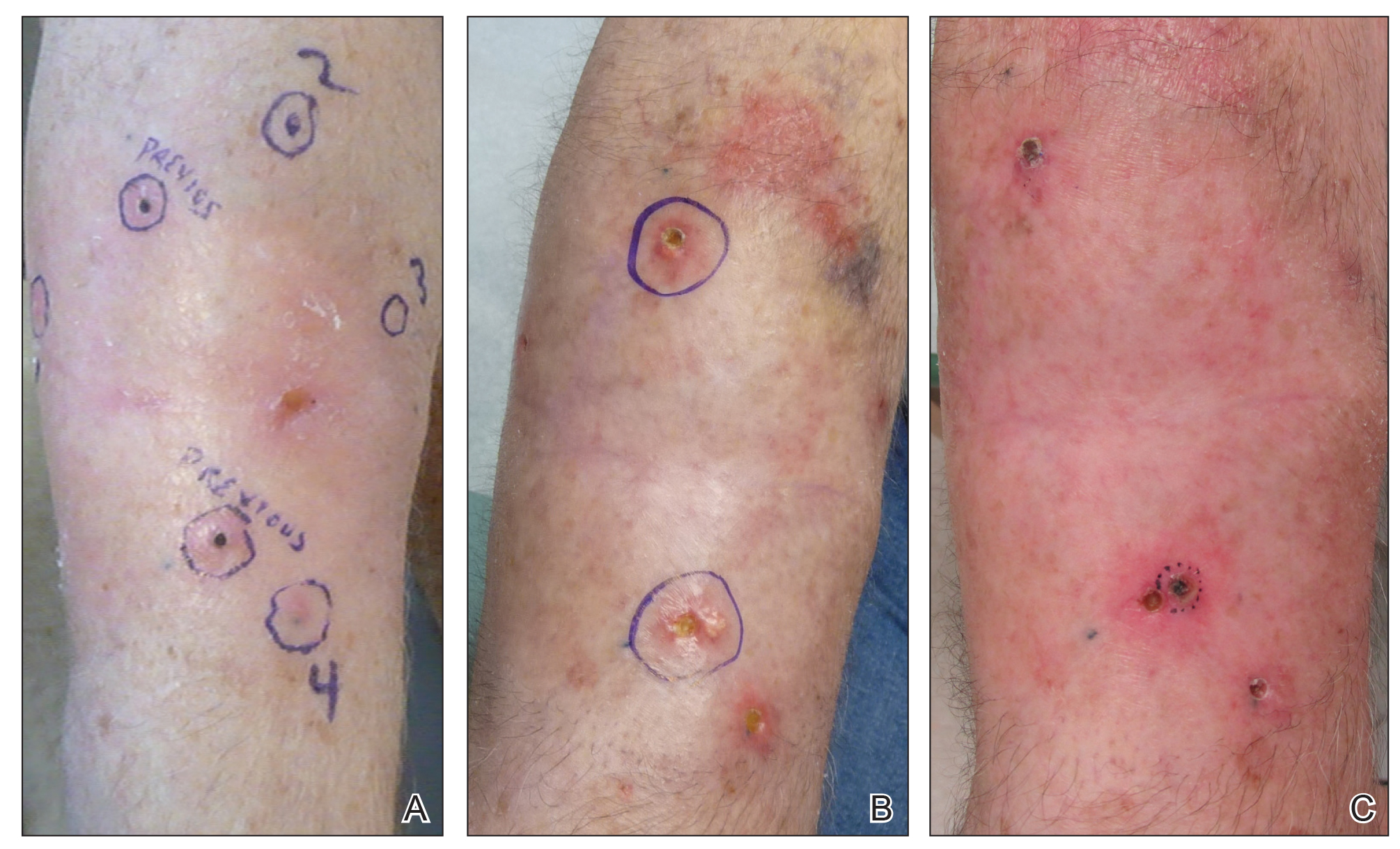

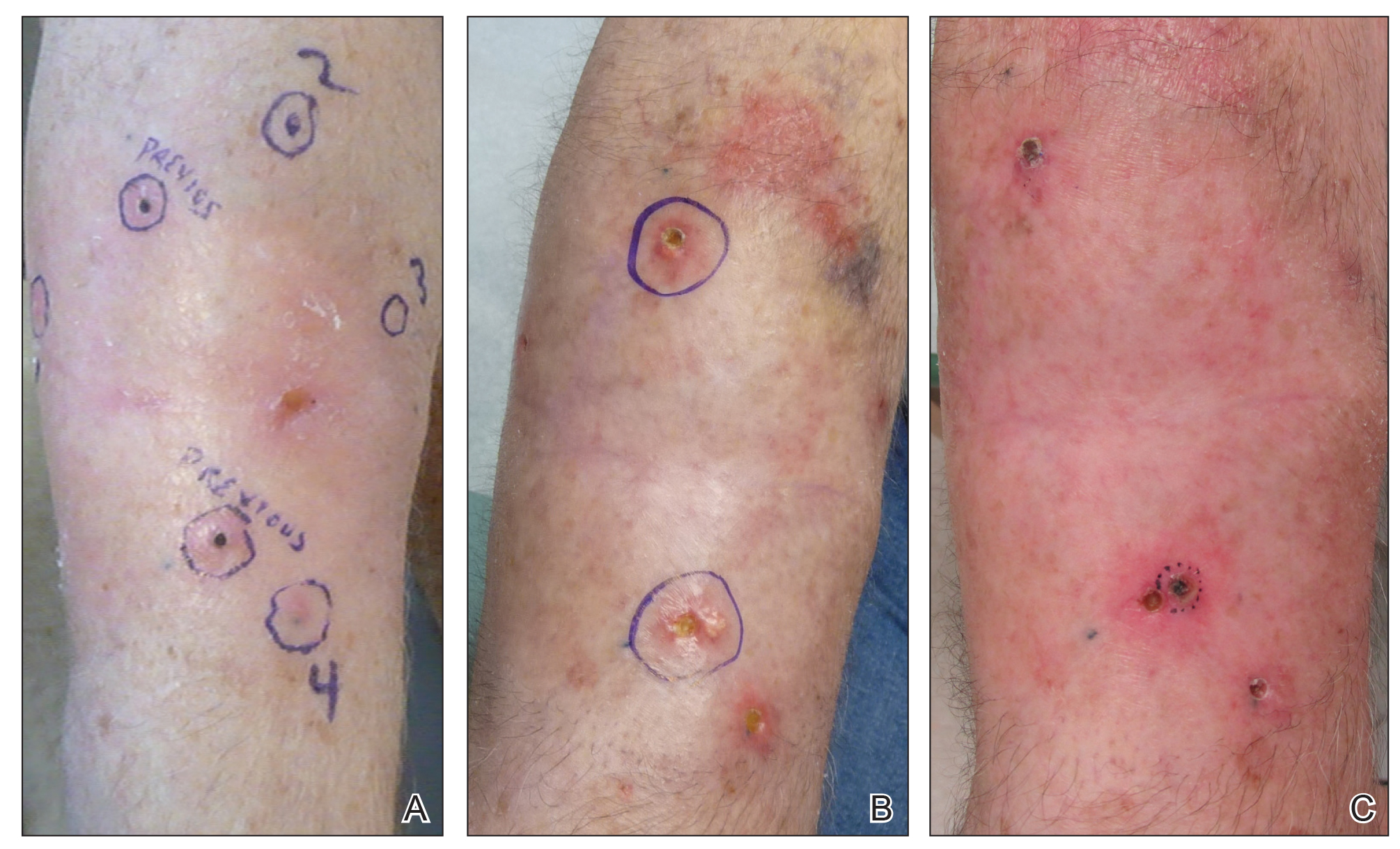

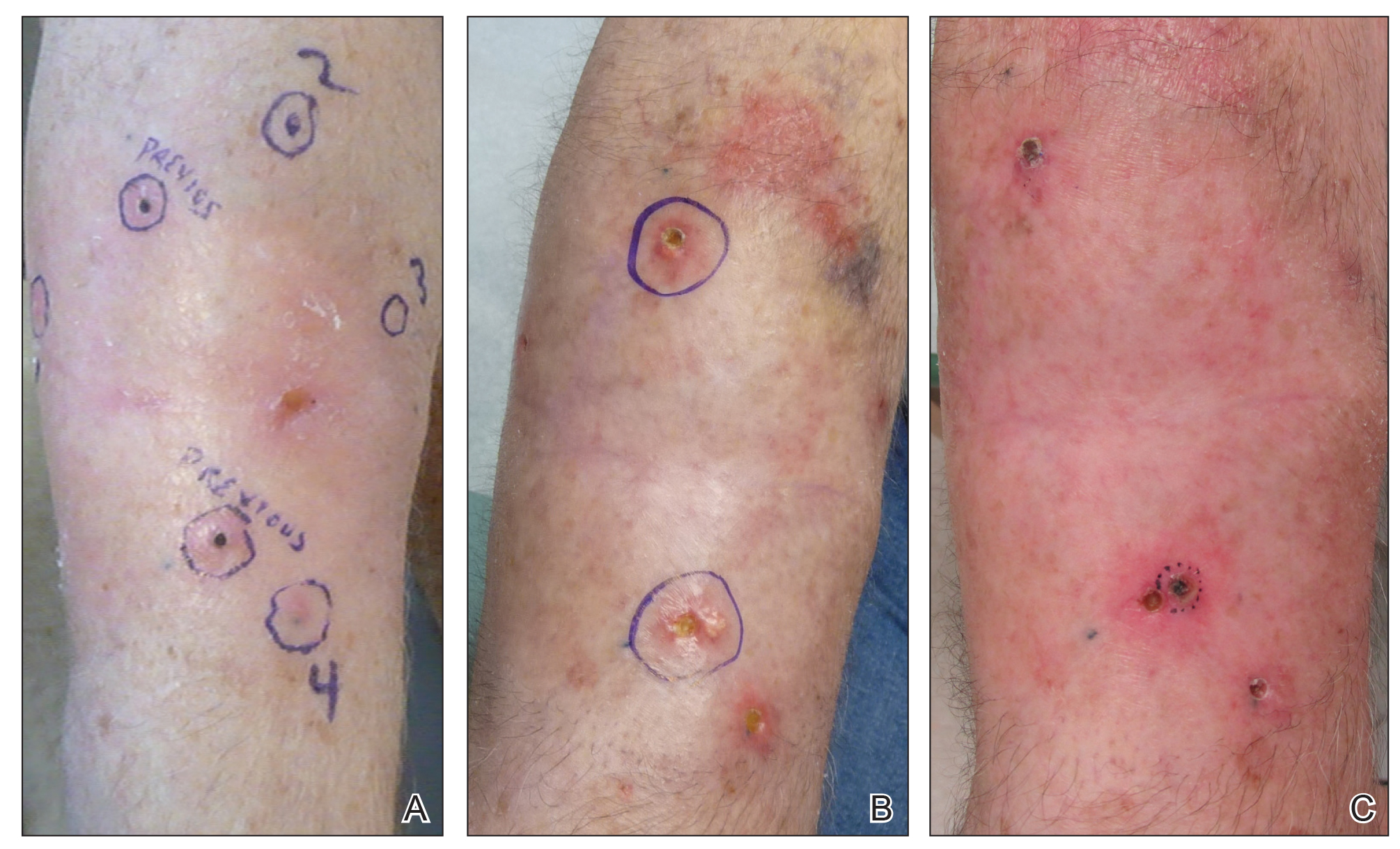

Another 4 weeks later the patient returned with a new lesion on the excision site. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. The lesion was treated with radiotherapy, with a 5800-cGy course completed 2 months later. The next month, 2 papules just adjacent to the radiotherapy treatment field were biopsied and diagnosed as well-differentiated SCC, KA type. One week later, 2 additional new papules adjacent to the radiotherapy treatment field were biopsied and diagnosed as moderately differentiated SCC, KA type. At this time, the patient had 4 biopsy-proven KAs on the right forearm in the area of prior radiation (Figure, A). The radiation oncologist felt that further radiation was no longer indicated. A consultation was sought with surgical oncology, and wide excision of the field with sentinel lymph node biopsy and skin grafting was recommended. Computed tomography with contrast of the chest and right arm ordered by surgical oncology did not reveal metastatic disease.

After discussion of the risks, alternatives, and benefits of surgery, the patient elected to try nonsurgical treatment. He was treated with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) cream 5% twice daily for 4 weeks. It was applied to the right arm from the elbow to the wrist and occluded under an elastic bandage. The patient stated that the biopsy sites became sore and inflamed during the treatment. After 4 weeks of treatment, all 4 KAs had healed without clinical evidence of tumor. During this time, however, the previously treated 2 sites had developed adjacent firm pink papules (Figure, B); these 2 lesions were then treated with intralesional 5-FU 50 mg/mL once weekly to resolution at 4 and 5 weeks, respectively. The proximal lesion was treated with 7.5 mg on week 1 and 5 mg on weeks 2, 3, and 4. The larger distal lesion was treated with 12.5 mg on week 1 and 5 mg on weeks 2, 3, 4, and 5. The volume injected was determined by ability to blanch and indurate the lesion and was decreased due to the shrinking size of the tumor. After 3 injections, both tumors had substantially decreased in size (Figure, C). The patient noted pain during injection but found the procedure tolerable and preferable to surgery. There were no other adverse events. At the end of treatment, both tumors had clinically resolved. No recurrence or development of new tumors was reported over 3 years of follow-up after the last injection.

Field cancerization was the outgrowth of the study of oral SCC in an effort to explain the development of multiple primary tumors and locally recurrent cancer.1,2 Histopathologically, the authors observed that oral cancer developed in multifocal areas of precancerous change, histologically abnormal hyperplastic tissue surrounded the tumors, oral cancer consisted of multiple independent areas that sometimes coalesced, and the persistence of abnormal tissue after surgery might explain local recurrences and the development of new lesions in a previously treated area.1,2 Since then, the concept has been applied to several other organ systems including the lungs, vulva, cervix, breasts, bladder, colon, and skin.2

In the skin, field cancerization involves clusters and contiguous patches of altered cells present in areas of chronic photodamage.2 Genetically altered fields form the foundation in which multiple clonally related neoplastic lesions can develop.2,3 These fields often remain after treatment of the primary tumor and may lead to new cancers that commonly are labeled as a second primary tumor or a local recurrence depending on the exact site and time interval.3 Brennan et al3 found clonal populations of infiltrating tumor cells harboring a p53 gene mutation in more than 50% of histopathologically negative surgical margins of patients with SCC of the head and neck. Furthermore, 40% of the patients with a margin positive for a p53 gene mutation had local recurrence vs none of the patients with negative margins.4 These findings were supported by several other studies where loss of heterozygosity, microsatellite alterations, chromosomal instability, or in situ hybridization was used to demonstrate genetically altered fields.2,4 Histopathologic patterns of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, focal acantholytic dyskeratosis, and pronounced acantholysis as found in Hailey-Hailey disease may be a consequence of clonal expansion of mutated keratinocytes because of long-term exposure to mutagens such as UV light and human papillomavirus.5

The development of an expanding neoplastic field appears to play an important role in cutaneous carcinogenesis. It is necessary to consider the cutaneous field cancerization as a highly photodamaged area that contains clinical and subclinical lesions.2-4 The treatment of cutaneous neoplasms, SCC in particular, should focus not only on the tumor itself but also on the surrounding tissue. Adjunctive field-directed therapies should be considered after treatment of the primary tumor.4

Our patient continued to develop SCCs on the right forearm after multiple excisions with clear margins and subsequently was treated with radiation therapy. He then developed 4 KAs after radiation therapy to the right forearm. Topical 5-FU is a well-described treatment of field cancerization.2 In our patient, 5-FU cream 5% applied twice daily from the wrist to the elbow under occlusion for 4 weeks led to the involution of all 4 KAs. During this time, our patient developed 2 additional firm pink papules near the previously treated sites, which resolved with intralesional 5-FU weekly for 4 and 5 weeks, respectively.

Intralesional 5-FU has been described for the treatment of multiple and difficult-to-treat KAs. It is an antimetabolite and structural analog of uracil that disrupts DNA and RNA synthesis. It is contraindicated in liver disease, pregnancy or breastfeeding, and allergy to the medication.6 Intralesional 5-FU dosing recommendations for KAs include use of a 50-mg/mL solution and injecting 0.1 to 1 mL until the lesion blanches in color, which may be repeated every 1 to 4 weeks.7,8 The maximum recommended daily dose is 800 mg.6 Pretreatment with intralesional 1% lidocaine has been recommended by some authors due to pain with injection.8 Recommendations for laboratory monitoring include a complete blood cell count with differential at baseline and weekly. Side effects include local pain, erythema, crusting, ulceration, and necrosis. Systemic side effects include cytopenia and gastrointestinal tract upset.6 Intralesional 5-FU has been used successfully in a single dose of 10 mg per lesion in combination with systemic acitretin for the treatment of multiple KAs induced by vemurafenib.9 It also has been effective in the treatment of multiple recurrent reactive KAs developing in surgical margins.7 A review article reported that the use of intralesional 5-FU produced a 98% cure rate in 56 treated KAs.6 Alternative intralesional agents that may be considered for KAs include methotrexate, bleomycin, and interferon alfa-2b.6,7

Field cancerization may cause the development of multiple clonally related neoplasms within a field of genetically altered cells that may continue to develop after excision with clear margins or radiation therapy. Given the success of treatment in our patient, we recommend consideration for topical and intralesional 5-FU in patients who develop SCCs and KAs within an area of field cancerization.

- Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. “Field cancerization” in oral stratified squamous epithelium. clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer. 1953;6:963-968.

- Torezan LA, Festa-Neto C. Cutaneous field cancerization: clinical, histopathological and therapeutic aspects. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:775-786.

- Brennan JA, Mao L, Hruban R, et al. Molecular assessment of histopathological staging in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:429-435.

- Braakhuis, BJ, Tabor MP, Kummer JA, et al. A genetic explanation of Slaughter’s concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1727-1730.

- Carlson AJ, Scott D, Wharton J, et al. Incidental histopathologic patterns: possible evidence of “field cancerization” surrounding skin tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:494-496.

- Kirby J, Miller C. Intralesional chemotherapy for nonmelanoma skin cancer: a practical review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:689-702.

- Hadley J, Tristani-Firouzi P, Florell S, et al. Case series of multiple recurrent reactive keratoacanthomas developing at surgical margins. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:2019-2024.

- Que S, Compton L, Schmults C. Eruptive squamous atypia (also known as eruptive keratoacanthoma): definition of the disease entity and successful management via intralesional 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:111-122.

- LaPresto L, Cranmer L, Morrison L, et al. A novel therapeutic combination approach for treating multiple vemurafenib-induced keratoacanthomas systemic acitretin and intralesional fluorouracil. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:279-281.

To the Editor:

The concept of field cancerization has been well described since its initial proposal by Slaughter et al1 in 1953. It describes a field of genetically altered cells where multiple clonally related neoplasms can develop.2,3 Treatment of patients with multiple neoplasms within an area of field cancerization can be especially challenging. We report a patient with field cancerization who had multiple squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) and keratoacanthomas (KAs) that arose within the field.

A 78-year-old man initially presented with a papule on the right forearm of 3 months’ duration. He had a medical history of cutaneous SCC, myocardial infarction, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, gout, and diverticulosis. He was not taking any chronic immunosuppressants that may have predisposed him to the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer. The papule was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated invasive SCC. A month later it was excised with clear margins.

Approximately 5 weeks after the excision, he returned with an enlarging lesion on the right forearm just medial to the excision site. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. Two months later the lesion was excised with clear margins. Four weeks later he returned with a new lesion adjacent to the medial aspect of the prior excision. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. Four weeks later the lesion was excised with clear margins.

Another 4 weeks later the patient returned with a new lesion on the excision site. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. The lesion was treated with radiotherapy, with a 5800-cGy course completed 2 months later. The next month, 2 papules just adjacent to the radiotherapy treatment field were biopsied and diagnosed as well-differentiated SCC, KA type. One week later, 2 additional new papules adjacent to the radiotherapy treatment field were biopsied and diagnosed as moderately differentiated SCC, KA type. At this time, the patient had 4 biopsy-proven KAs on the right forearm in the area of prior radiation (Figure, A). The radiation oncologist felt that further radiation was no longer indicated. A consultation was sought with surgical oncology, and wide excision of the field with sentinel lymph node biopsy and skin grafting was recommended. Computed tomography with contrast of the chest and right arm ordered by surgical oncology did not reveal metastatic disease.

After discussion of the risks, alternatives, and benefits of surgery, the patient elected to try nonsurgical treatment. He was treated with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) cream 5% twice daily for 4 weeks. It was applied to the right arm from the elbow to the wrist and occluded under an elastic bandage. The patient stated that the biopsy sites became sore and inflamed during the treatment. After 4 weeks of treatment, all 4 KAs had healed without clinical evidence of tumor. During this time, however, the previously treated 2 sites had developed adjacent firm pink papules (Figure, B); these 2 lesions were then treated with intralesional 5-FU 50 mg/mL once weekly to resolution at 4 and 5 weeks, respectively. The proximal lesion was treated with 7.5 mg on week 1 and 5 mg on weeks 2, 3, and 4. The larger distal lesion was treated with 12.5 mg on week 1 and 5 mg on weeks 2, 3, 4, and 5. The volume injected was determined by ability to blanch and indurate the lesion and was decreased due to the shrinking size of the tumor. After 3 injections, both tumors had substantially decreased in size (Figure, C). The patient noted pain during injection but found the procedure tolerable and preferable to surgery. There were no other adverse events. At the end of treatment, both tumors had clinically resolved. No recurrence or development of new tumors was reported over 3 years of follow-up after the last injection.

Field cancerization was the outgrowth of the study of oral SCC in an effort to explain the development of multiple primary tumors and locally recurrent cancer.1,2 Histopathologically, the authors observed that oral cancer developed in multifocal areas of precancerous change, histologically abnormal hyperplastic tissue surrounded the tumors, oral cancer consisted of multiple independent areas that sometimes coalesced, and the persistence of abnormal tissue after surgery might explain local recurrences and the development of new lesions in a previously treated area.1,2 Since then, the concept has been applied to several other organ systems including the lungs, vulva, cervix, breasts, bladder, colon, and skin.2

In the skin, field cancerization involves clusters and contiguous patches of altered cells present in areas of chronic photodamage.2 Genetically altered fields form the foundation in which multiple clonally related neoplastic lesions can develop.2,3 These fields often remain after treatment of the primary tumor and may lead to new cancers that commonly are labeled as a second primary tumor or a local recurrence depending on the exact site and time interval.3 Brennan et al3 found clonal populations of infiltrating tumor cells harboring a p53 gene mutation in more than 50% of histopathologically negative surgical margins of patients with SCC of the head and neck. Furthermore, 40% of the patients with a margin positive for a p53 gene mutation had local recurrence vs none of the patients with negative margins.4 These findings were supported by several other studies where loss of heterozygosity, microsatellite alterations, chromosomal instability, or in situ hybridization was used to demonstrate genetically altered fields.2,4 Histopathologic patterns of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, focal acantholytic dyskeratosis, and pronounced acantholysis as found in Hailey-Hailey disease may be a consequence of clonal expansion of mutated keratinocytes because of long-term exposure to mutagens such as UV light and human papillomavirus.5

The development of an expanding neoplastic field appears to play an important role in cutaneous carcinogenesis. It is necessary to consider the cutaneous field cancerization as a highly photodamaged area that contains clinical and subclinical lesions.2-4 The treatment of cutaneous neoplasms, SCC in particular, should focus not only on the tumor itself but also on the surrounding tissue. Adjunctive field-directed therapies should be considered after treatment of the primary tumor.4

Our patient continued to develop SCCs on the right forearm after multiple excisions with clear margins and subsequently was treated with radiation therapy. He then developed 4 KAs after radiation therapy to the right forearm. Topical 5-FU is a well-described treatment of field cancerization.2 In our patient, 5-FU cream 5% applied twice daily from the wrist to the elbow under occlusion for 4 weeks led to the involution of all 4 KAs. During this time, our patient developed 2 additional firm pink papules near the previously treated sites, which resolved with intralesional 5-FU weekly for 4 and 5 weeks, respectively.

Intralesional 5-FU has been described for the treatment of multiple and difficult-to-treat KAs. It is an antimetabolite and structural analog of uracil that disrupts DNA and RNA synthesis. It is contraindicated in liver disease, pregnancy or breastfeeding, and allergy to the medication.6 Intralesional 5-FU dosing recommendations for KAs include use of a 50-mg/mL solution and injecting 0.1 to 1 mL until the lesion blanches in color, which may be repeated every 1 to 4 weeks.7,8 The maximum recommended daily dose is 800 mg.6 Pretreatment with intralesional 1% lidocaine has been recommended by some authors due to pain with injection.8 Recommendations for laboratory monitoring include a complete blood cell count with differential at baseline and weekly. Side effects include local pain, erythema, crusting, ulceration, and necrosis. Systemic side effects include cytopenia and gastrointestinal tract upset.6 Intralesional 5-FU has been used successfully in a single dose of 10 mg per lesion in combination with systemic acitretin for the treatment of multiple KAs induced by vemurafenib.9 It also has been effective in the treatment of multiple recurrent reactive KAs developing in surgical margins.7 A review article reported that the use of intralesional 5-FU produced a 98% cure rate in 56 treated KAs.6 Alternative intralesional agents that may be considered for KAs include methotrexate, bleomycin, and interferon alfa-2b.6,7

Field cancerization may cause the development of multiple clonally related neoplasms within a field of genetically altered cells that may continue to develop after excision with clear margins or radiation therapy. Given the success of treatment in our patient, we recommend consideration for topical and intralesional 5-FU in patients who develop SCCs and KAs within an area of field cancerization.

To the Editor:

The concept of field cancerization has been well described since its initial proposal by Slaughter et al1 in 1953. It describes a field of genetically altered cells where multiple clonally related neoplasms can develop.2,3 Treatment of patients with multiple neoplasms within an area of field cancerization can be especially challenging. We report a patient with field cancerization who had multiple squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) and keratoacanthomas (KAs) that arose within the field.

A 78-year-old man initially presented with a papule on the right forearm of 3 months’ duration. He had a medical history of cutaneous SCC, myocardial infarction, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, gout, and diverticulosis. He was not taking any chronic immunosuppressants that may have predisposed him to the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer. The papule was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated invasive SCC. A month later it was excised with clear margins.

Approximately 5 weeks after the excision, he returned with an enlarging lesion on the right forearm just medial to the excision site. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. Two months later the lesion was excised with clear margins. Four weeks later he returned with a new lesion adjacent to the medial aspect of the prior excision. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. Four weeks later the lesion was excised with clear margins.

Another 4 weeks later the patient returned with a new lesion on the excision site. The lesion was biopsied and diagnosed as a well-differentiated SCC. The lesion was treated with radiotherapy, with a 5800-cGy course completed 2 months later. The next month, 2 papules just adjacent to the radiotherapy treatment field were biopsied and diagnosed as well-differentiated SCC, KA type. One week later, 2 additional new papules adjacent to the radiotherapy treatment field were biopsied and diagnosed as moderately differentiated SCC, KA type. At this time, the patient had 4 biopsy-proven KAs on the right forearm in the area of prior radiation (Figure, A). The radiation oncologist felt that further radiation was no longer indicated. A consultation was sought with surgical oncology, and wide excision of the field with sentinel lymph node biopsy and skin grafting was recommended. Computed tomography with contrast of the chest and right arm ordered by surgical oncology did not reveal metastatic disease.

After discussion of the risks, alternatives, and benefits of surgery, the patient elected to try nonsurgical treatment. He was treated with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) cream 5% twice daily for 4 weeks. It was applied to the right arm from the elbow to the wrist and occluded under an elastic bandage. The patient stated that the biopsy sites became sore and inflamed during the treatment. After 4 weeks of treatment, all 4 KAs had healed without clinical evidence of tumor. During this time, however, the previously treated 2 sites had developed adjacent firm pink papules (Figure, B); these 2 lesions were then treated with intralesional 5-FU 50 mg/mL once weekly to resolution at 4 and 5 weeks, respectively. The proximal lesion was treated with 7.5 mg on week 1 and 5 mg on weeks 2, 3, and 4. The larger distal lesion was treated with 12.5 mg on week 1 and 5 mg on weeks 2, 3, 4, and 5. The volume injected was determined by ability to blanch and indurate the lesion and was decreased due to the shrinking size of the tumor. After 3 injections, both tumors had substantially decreased in size (Figure, C). The patient noted pain during injection but found the procedure tolerable and preferable to surgery. There were no other adverse events. At the end of treatment, both tumors had clinically resolved. No recurrence or development of new tumors was reported over 3 years of follow-up after the last injection.

Field cancerization was the outgrowth of the study of oral SCC in an effort to explain the development of multiple primary tumors and locally recurrent cancer.1,2 Histopathologically, the authors observed that oral cancer developed in multifocal areas of precancerous change, histologically abnormal hyperplastic tissue surrounded the tumors, oral cancer consisted of multiple independent areas that sometimes coalesced, and the persistence of abnormal tissue after surgery might explain local recurrences and the development of new lesions in a previously treated area.1,2 Since then, the concept has been applied to several other organ systems including the lungs, vulva, cervix, breasts, bladder, colon, and skin.2

In the skin, field cancerization involves clusters and contiguous patches of altered cells present in areas of chronic photodamage.2 Genetically altered fields form the foundation in which multiple clonally related neoplastic lesions can develop.2,3 These fields often remain after treatment of the primary tumor and may lead to new cancers that commonly are labeled as a second primary tumor or a local recurrence depending on the exact site and time interval.3 Brennan et al3 found clonal populations of infiltrating tumor cells harboring a p53 gene mutation in more than 50% of histopathologically negative surgical margins of patients with SCC of the head and neck. Furthermore, 40% of the patients with a margin positive for a p53 gene mutation had local recurrence vs none of the patients with negative margins.4 These findings were supported by several other studies where loss of heterozygosity, microsatellite alterations, chromosomal instability, or in situ hybridization was used to demonstrate genetically altered fields.2,4 Histopathologic patterns of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, focal acantholytic dyskeratosis, and pronounced acantholysis as found in Hailey-Hailey disease may be a consequence of clonal expansion of mutated keratinocytes because of long-term exposure to mutagens such as UV light and human papillomavirus.5

The development of an expanding neoplastic field appears to play an important role in cutaneous carcinogenesis. It is necessary to consider the cutaneous field cancerization as a highly photodamaged area that contains clinical and subclinical lesions.2-4 The treatment of cutaneous neoplasms, SCC in particular, should focus not only on the tumor itself but also on the surrounding tissue. Adjunctive field-directed therapies should be considered after treatment of the primary tumor.4

Our patient continued to develop SCCs on the right forearm after multiple excisions with clear margins and subsequently was treated with radiation therapy. He then developed 4 KAs after radiation therapy to the right forearm. Topical 5-FU is a well-described treatment of field cancerization.2 In our patient, 5-FU cream 5% applied twice daily from the wrist to the elbow under occlusion for 4 weeks led to the involution of all 4 KAs. During this time, our patient developed 2 additional firm pink papules near the previously treated sites, which resolved with intralesional 5-FU weekly for 4 and 5 weeks, respectively.

Intralesional 5-FU has been described for the treatment of multiple and difficult-to-treat KAs. It is an antimetabolite and structural analog of uracil that disrupts DNA and RNA synthesis. It is contraindicated in liver disease, pregnancy or breastfeeding, and allergy to the medication.6 Intralesional 5-FU dosing recommendations for KAs include use of a 50-mg/mL solution and injecting 0.1 to 1 mL until the lesion blanches in color, which may be repeated every 1 to 4 weeks.7,8 The maximum recommended daily dose is 800 mg.6 Pretreatment with intralesional 1% lidocaine has been recommended by some authors due to pain with injection.8 Recommendations for laboratory monitoring include a complete blood cell count with differential at baseline and weekly. Side effects include local pain, erythema, crusting, ulceration, and necrosis. Systemic side effects include cytopenia and gastrointestinal tract upset.6 Intralesional 5-FU has been used successfully in a single dose of 10 mg per lesion in combination with systemic acitretin for the treatment of multiple KAs induced by vemurafenib.9 It also has been effective in the treatment of multiple recurrent reactive KAs developing in surgical margins.7 A review article reported that the use of intralesional 5-FU produced a 98% cure rate in 56 treated KAs.6 Alternative intralesional agents that may be considered for KAs include methotrexate, bleomycin, and interferon alfa-2b.6,7

Field cancerization may cause the development of multiple clonally related neoplasms within a field of genetically altered cells that may continue to develop after excision with clear margins or radiation therapy. Given the success of treatment in our patient, we recommend consideration for topical and intralesional 5-FU in patients who develop SCCs and KAs within an area of field cancerization.

- Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. “Field cancerization” in oral stratified squamous epithelium. clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer. 1953;6:963-968.

- Torezan LA, Festa-Neto C. Cutaneous field cancerization: clinical, histopathological and therapeutic aspects. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:775-786.

- Brennan JA, Mao L, Hruban R, et al. Molecular assessment of histopathological staging in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:429-435.

- Braakhuis, BJ, Tabor MP, Kummer JA, et al. A genetic explanation of Slaughter’s concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1727-1730.

- Carlson AJ, Scott D, Wharton J, et al. Incidental histopathologic patterns: possible evidence of “field cancerization” surrounding skin tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:494-496.

- Kirby J, Miller C. Intralesional chemotherapy for nonmelanoma skin cancer: a practical review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:689-702.

- Hadley J, Tristani-Firouzi P, Florell S, et al. Case series of multiple recurrent reactive keratoacanthomas developing at surgical margins. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:2019-2024.

- Que S, Compton L, Schmults C. Eruptive squamous atypia (also known as eruptive keratoacanthoma): definition of the disease entity and successful management via intralesional 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:111-122.

- LaPresto L, Cranmer L, Morrison L, et al. A novel therapeutic combination approach for treating multiple vemurafenib-induced keratoacanthomas systemic acitretin and intralesional fluorouracil. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:279-281.

- Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. “Field cancerization” in oral stratified squamous epithelium. clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer. 1953;6:963-968.

- Torezan LA, Festa-Neto C. Cutaneous field cancerization: clinical, histopathological and therapeutic aspects. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:775-786.

- Brennan JA, Mao L, Hruban R, et al. Molecular assessment of histopathological staging in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:429-435.

- Braakhuis, BJ, Tabor MP, Kummer JA, et al. A genetic explanation of Slaughter’s concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1727-1730.

- Carlson AJ, Scott D, Wharton J, et al. Incidental histopathologic patterns: possible evidence of “field cancerization” surrounding skin tumors. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:494-496.

- Kirby J, Miller C. Intralesional chemotherapy for nonmelanoma skin cancer: a practical review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:689-702.

- Hadley J, Tristani-Firouzi P, Florell S, et al. Case series of multiple recurrent reactive keratoacanthomas developing at surgical margins. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:2019-2024.

- Que S, Compton L, Schmults C. Eruptive squamous atypia (also known as eruptive keratoacanthoma): definition of the disease entity and successful management via intralesional 5-fluorouracil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:111-122.

- LaPresto L, Cranmer L, Morrison L, et al. A novel therapeutic combination approach for treating multiple vemurafenib-induced keratoacanthomas systemic acitretin and intralesional fluorouracil. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:279-281.

Merkel Cell Carcinoma: Presentation, Pathogenesis, and Spontaneous Regression

Spontaneous Regression of Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare, rapidly growing, aggressive neoplasm with a generally poor prognosis. The cells of origin are highly anaplastic and share structural and immunohistochemical features with various neuroectodermally derived cells. Although Merkel cells, which are slow-acting cutaneous mechanoreceptors located in the basal layer of the epidermis, and MCC share immunohistochemical and ultrastructural features, there is limited evidence of a direct histogenetic relationship between the two.1,2 Additionally, some extracutaneous neuroendocrine tumors have features similar to MCC; therefore, although it may be more accurate and perhaps more practical to describe these lesions as primary neuroendocrine carcinomas of the skin, the term MCC is more commonly used both in the literature and in clinical practice.1,2

Merkel cell carcinoma typically presents in the head and neck region in white patients older than 70 years of age and in the immunocompromised population.3-6 The mean age of diagnosis is 76 years for women and 74 years for men.7 The incidence of MCC in the United States tripled over a 15-year period, and there are approximately 1500 new cases of MCC diagnosed each year, making it about 40 times less common than melanoma.8 The 5-year survival rate for patients without lymph node involvement is 75%, whereas the 5-year survival rate for patients with distant metastases is 25%.9

Merkel cell carcinoma is thought to develop through 1 of 2 distinct pathways. In a virally mediated pathway, which represents at least 80% of cases, the Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCV) monoclonally integrates into the host genome and promotes oncogenesis via altered p53 and retinoblastoma protein expression.10-12 The remainder of cases are believed to develop via a nonvirally mediated pathway in which genetic anomalies, immune status, and environmental factors influence oncogenesis.10-13

Due to the similarity between MCC and metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasms, especially small-cell lung carcinomas, immunohistochemistry is important in making the diagnosis. Cytokeratin 20 and neuron-specific enolase positivity and thyroid transcription factor 1 negativity are the most useful markers in identifying MCC.

Regression of MCC is a very rare and poorly understood event. A 2010 review of the literature described 22 cases of spontaneous regression.14 We report a rare case of rapid and complete regression of MCC following punch biopsy in a 96-year-old woman.

Case Report

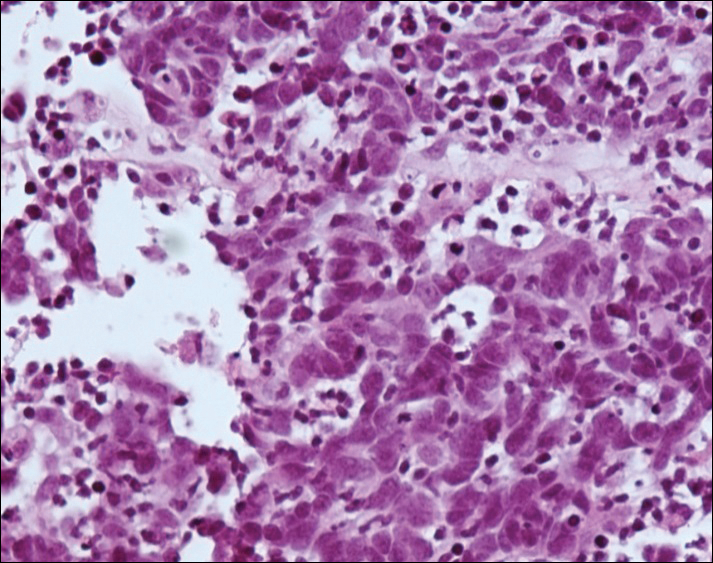

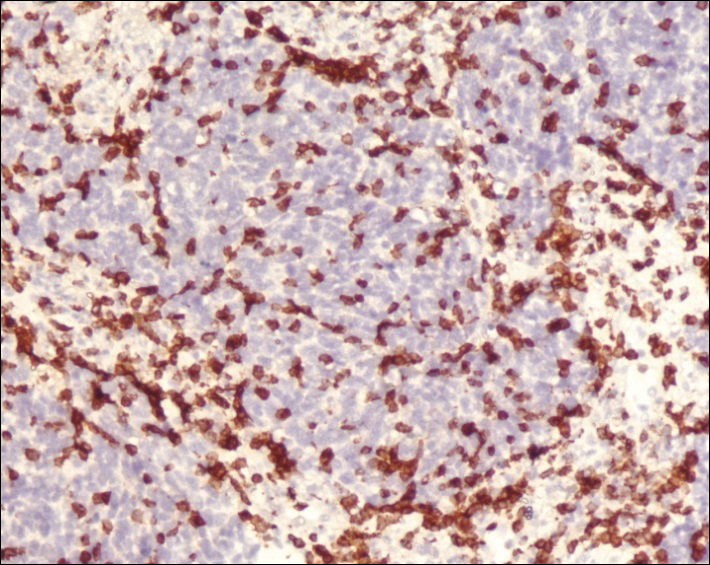

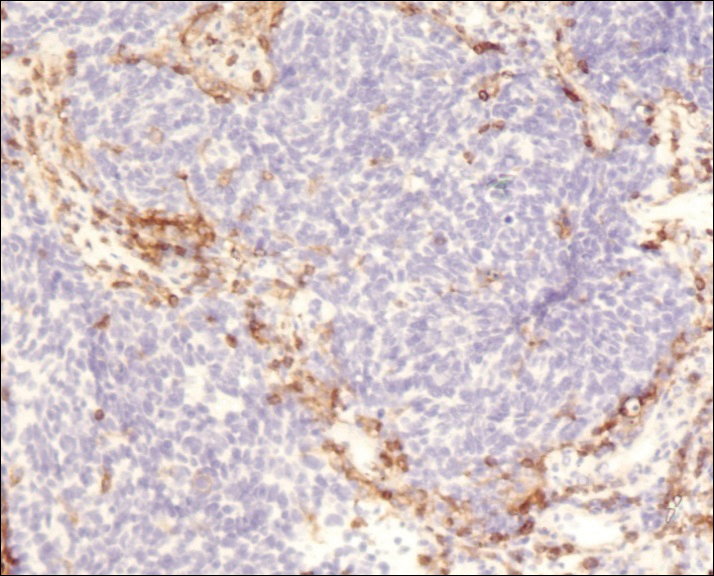

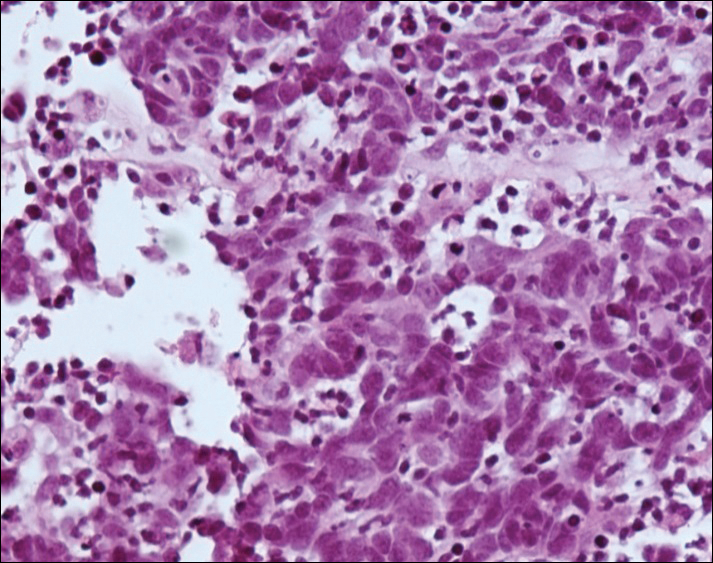

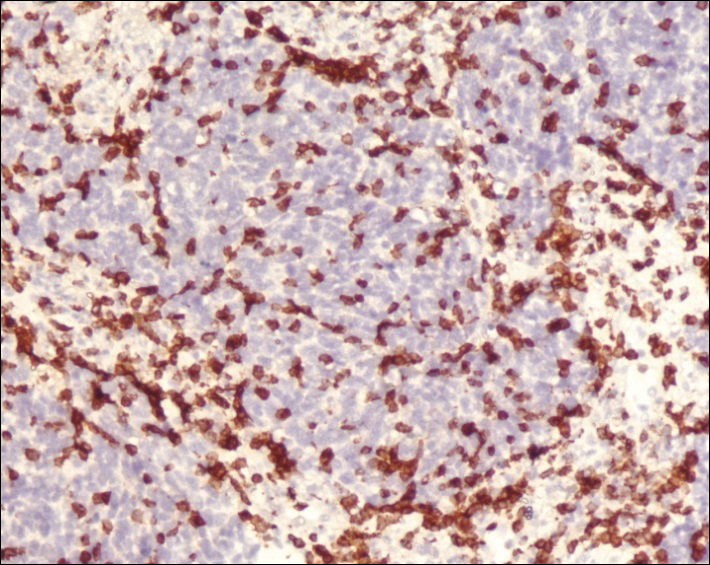

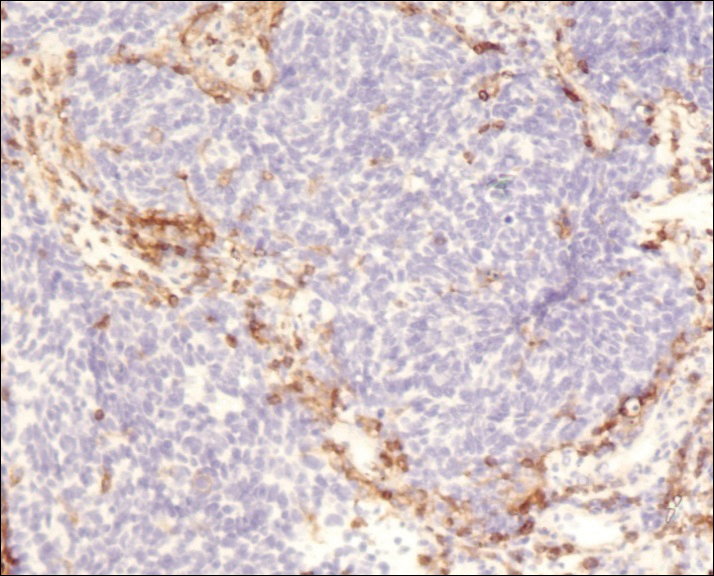

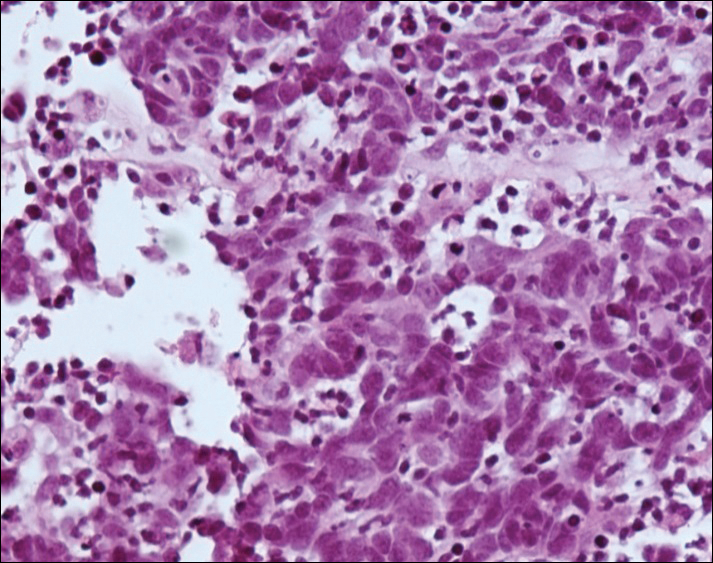

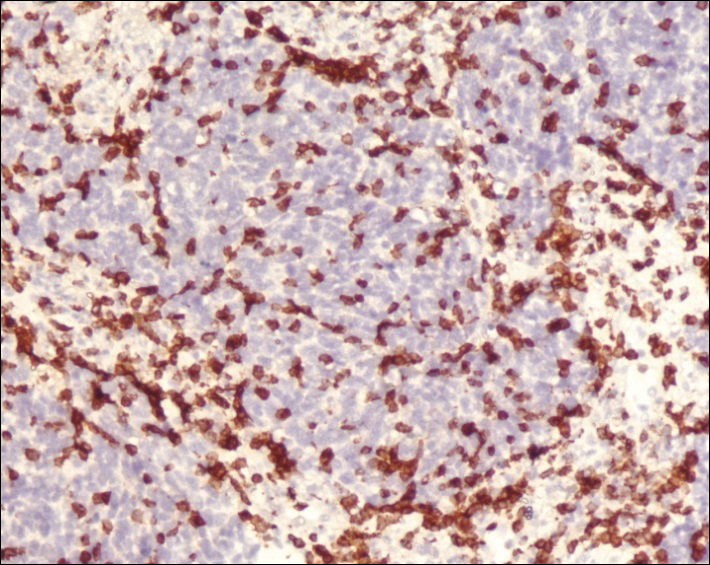

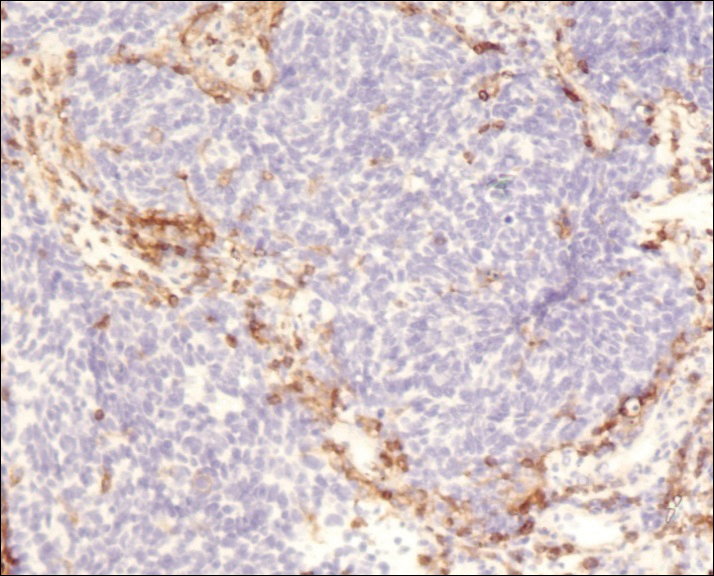

A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained at a follow-up visit 4 weeks later (12 weeks after the reported onset of the lesion). Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed a small-cell neoplasm with stippled nuclei and scant cytoplasm forming a nested and somewhat trabecular pattern. Mitotic activity, apoptosis, and nuclear molding also were present (Figure 2). The tumor cells were positive for cytokeratin 20 with a dotlike, paranuclear pattern (Figure 3). Staining for CAM 5.2 also was positive. Cytokeratin 5/6, human melanoma black 45, and leukocyte common antigen were negative. The immunophenotyping of the lymphocytic response to the tumor showed that the majority of intratumoral lymphocytes were CD8 positive (Figure 4). CD4-positive lymphocytes were predominantly seen at the periphery of the tumor nests without tumor infiltration (Figure 5). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of MCC was made. The patient’s family declined treatment based on her advanced age and current health status, which included advanced dementia.

Two weeks after the punch biopsy, the lesion had noticeably decreased in size and lost its dome-shaped appearance. Within 8 weeks after biopsy (20 weeks since the lesion first appeared), the lesion had completely resolved (Figure 6). The patient was lost to follow-up months later, but no recurrence of the lesion was reported.

Comment

Spontaneous regression is not unique to MCC, as this phenomenon also has been reported in keratoacanthoma, lymphoma, basal cell carcinoma, and melanoma.15 Complete spontaneous regression is defined as occurring in the absence of therapy that is intended to have a treatment effect.15,16 Spontaneous regression is estimated to occur in malignant neoplasms at a rate of 1 case per 60,000 to 100,000 (approximately 0.0013% of all malignant neoplasms).17 Considering the reported prevalence of MCC and the number of cases that have been known to regress, the estimated incidence of complete spontaneous regression may be as high as 1.5%.14 Though spontaneous regression of MCC is more prevalent than expected, it still is considered a rare phenomenon. A 2010 review of the literature yielded 22 cases of complete spontaneous regression of MCC.14 No recurrences have been observed; however, follow-up was relatively short in some cases.

In a unique report by Bertolotti et al,18 a patient with MCC on the nasal tip presented 4 weeks after biopsy with complete spontaneous regression of the tumor, which was associated with bilateral cervical lymph node involvement as noted by hypermetabolic uptake on positron emission tomography scanning. The patient underwent radiation therapy and was disease free at 12 months’ follow-up.18

Complete spontaneous regression has been described in MCC patients with local disease, regional recurrences, and metastatic disease.19 In

The histopathologic features observed in our case, specifically intratumoral CD8-positive cytotoxic lymphocytes and peritumoral CD4-positive cells, were similar to the findings in other reported cases. In one series of 2 cases, the one case showed scar tissue with a moderate, predominantly T-lymphocytic infiltrate and no tumor cells, and the second showed cellular proliferation in the deep dermis with dense lymphocytic infiltrates primarily composed of CD3-positive T cells.14 Other studies of regression of both localized and metastatic MCC demonstrated infiltration by CD4-positive, CD8-positive, and CD3-positive lymphocytes and foamy macrophages.21-23

The discovery of the MCV was one of the most important advances in elucidating the pathogenesis of MCC.10,24-26 Merkel cell polyomavirus DNA has been detected in a majority of MCC cases.25,27 Viral integration has been shown to take place early, prior to tumor clonal expansion.10 Importantly, not all cases of MCC show MCV infection, and MCV infection is not exclusive to MCC.28 Merkel cell polyomavirus is considered to be part of the normal human flora, and asymptomatic infection is quite common.29 It has been identified in 80% of adults older than 50 years of age and, interestingly, in 35% of children by 13 years of age or younger.30,31 It remains unclear what role the presence of MCV plays in determining MCC prognosis. Several reports have demonstrated lower disease-specific mortality associated with MCV-positive MCC.32-35 In contrast, Schrama et al36 correlated the MCV status of 174 MCC tumors and found no difference in clinical behavior or prognosis between MCV-positive and MCV-negative MCCs.

Immunosuppression also may play a role in the development of MCC.5,25 There is increased prevalence of MCC in the human immunodeficiency virus–positive population, as well as in organ-transplant recipients and patients with leukemia. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia seems to be the most frequent neoplasia associated with development of MCC.37

The mechanism of MCC regression remains unclear, but many investigators emphasize the importance of T-cell–mediated immunity.16,21-23,38,39 Apoptosis also has been shown to play an important role.40 Our case showed tumor-infiltrating CD8-positive lymphocytes and CD4-positive lymphocytes present predominantly at the periphery of the tumor, with close proximity to the tumor nests but with no tumor infiltration (Figure 3). This distribution was consistently present in multiple sections of the tumor. These findings are consistent with prior reports of both CD4-positive and CD8-positive T lymphocytes associated with MCC regression. Our findings confirm that immune response may play an important role in spontaneous regression of MCC.

There is much speculation regarding the initial biopsy of an MCC lesion (or other traumatic event) and its role in tumor regression. Koba et al41 examined the effect of biopsy on CD8-positive lymphocytic infiltration of MCC tumor cells and found that biopsy does not commonly alter intratumoral CD8-positive infiltration. These findings suggest trauma does not directly induce immunologic recognition of this cancer.

Conclusion

We report a case of complete spontaneous regression of a localized MCC following a punch biopsy. The histopathology showed a brisk T-lymphocyte response with intratumoral CD8-positive cytotoxic lymphocytes and peritumoral CD4-positive cells. The age and clinical profile of our patient as well as the clinicopathologic characteristics of the tumor regression are similar to other reported cases. Further research is needed to elucidate the mechanism of MCC regression, and a better understanding of this fascinating phenomenon could help in development of new immunotherapeutic approaches.

- Sibley RK, Dehner LP, Rosai J. Primary neuroendocrine (Merkel cell?) carcinoma of the skin. I. a clinicopathologic and ultrastructural study of 43 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:95-108.

- Sibley RK, Dahl D. Primary neuroendocrine (Merkel cell?) carcinoma of the skin. II. an immunocytochemical study of 21 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:109-116.

- Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

- Penn I, First MR. Merkel’s cell carcinoma in organ recipients: report of 41 cases. Transplantation. 1999;68:1717-1721.

- Gooptu C, Woolloons A, Ross J, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma arising after therapeutic immunosuppression. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:637-641.

- Plunkett TA, Harris AJ, Ogg CS, et al. The treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma and its association with immunosuppression. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:345-346.

- Calder KB, Smoller BR. New insights into Merkel cell carcinoma. Adv Anat Pathol. 2010;17:155-161.

- Hodgson NC. Merkel cell carcinoma: changing incidence trends. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:1-4.

- Agelli M, Clegg LX. Epidemiology of primary Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:832-841.

- Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, et al. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096-1100.

- Amber K, McLeod MP, Nouri K. The Merkel cell polyomavirus and its involvement in Merkel cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:232-238.

- Decaprio JA. Does detection of Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma provide prognostic information? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:905-907.

- Popp S, Waltering S, Herbst C, et al. UV-B-type mutations and chromosomal imbalances indicate common pathways for the development of Merkel and skin squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:352-360.

- Ciudad C, Avilés JA, Alfageme F, et al. Spontaneous regression in Merkel cell carcinoma: report of two cases with description of dermoscopic features and review of literature. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:687-693.

- O’Rourke MGE, Bell JR. Merkel cell tumor with spontaneous regression. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1986;12:994-997.

- Connelly TJ, Cribier B, Brown TJ, et al. Complete spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma: a review of 10 reported cases. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:853-856.

- Cole WH. Efforts to explain spontaneous regression of cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1981;17:201-209.

- Bertolotti A, Conte H, Francois L, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: complete clinical remission associated with disease progression. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:501-502.

- Pang C, Sharma D, Sankar T. Spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature [published online November 13, 2014]. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;7C:104-108.

- Richetta AG, Mancini M, Torroni A, et al. Total spontaneous regression of advanced Merkel cell carcinoma after biopsy: review and a new case. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:815-822.

- Vesely MJ, Murray DJ, Neligan PC, et al. Complete spontaneous regression in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61:165-171.

- Kayashima K, Ono T, Johno M, et al. Spontaneous regression in Merkel cell (neuroendocrine) carcinoma of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:550-553.

- Maruo K, Kayashima KI, Ono T. Regressing Merkel cell carcinoma-a case showing replacement of tumour cells by foamy cells. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:1184-1189.

- Duncavage E, Zehnbauer B, Pfeifer J. Prevalence of Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:516-521.

- Kassem A, Schopflin A, Diaz C, et al. Frequent detection of Merkel cell polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinomas and identification of unique deletion in the VP1 gene. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5009-5013.

- Becker J, Schrama D, Houben R. Merkel cell carcinoma. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:1-8.

- Haitz KA, Rady PL, Nguyen HP, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus DNA detection in a patient with Merkel cell carcinoma and multiple other skin cancers. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:442-444.

- Andres C, Puchta U, Sander CA, et al. Prevalence of Merkel cell polyomavirus DNA in cutaneous lymphomas, pseudolymphomas, and inflammatory skin diseases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:593-598.

- Showalter RM, Pastrana DV, Pumphrey KA, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus and two previously unknown polyomaviruses are chronically shed from human skin. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:509-515.

- Tolstov YL, Pastrana DV, Feng H, et al. Human Merkel cell polyomavirus infection II. MCV is a common human infection that can be detected by conformational capsid epitope immunoassays. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1250-1256.

- Chen T, Hedman L, Mattila PS, et al. Serological evidence of Merkel cell polyomavirus primary infections in childhood. J Clin Virol. 2011;50:125-129.

- Laude HC, Jonchère B, Maubec E, et al. Distinct Merkel cell polyomavirus molecular features in tumour and non tumour specimens from patients with Merkel cell carcinoma. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001076.

- Waltari M, Sihto H, Kukko H, et al. Association of Merkel cell polyomavirus infection with tumor p53, KIT, stem cell factor, PDGFR-alpha and survival in Merkel cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:619-628.

- Sihto H, Kukko H, Koljonen V, et al. Clinical factors associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus infection in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:938-945.

- Paulson KG, Lemos BD, Feng B, et al. Array-CGH reveals recurrent genomic changes in Merkel cell carcinoma including amplification of L-Myc. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1547-1555.

- Schrama D, Peitsch WK, Zapatka M, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus status is not associated with clinical course of Merkel cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1631-1638.

- Tadmor T, Aviv A, Polliack A. Merkel cell carcinoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia and other lymphoproliferative disorders: an old bond with possible new viral ties. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:250-256.

- Wooff J, Trites JR, Walsh NM, et al. Complete spontaneous regression of metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:614-617.

- Turk TO, Smoljan I, Nacinovic A, et al. Spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:7270.

- Mori Y, Tanaka K, Cui CY, et al. A study of apoptosis in Merkel cell carcinoma. an immunohistochemical, ultrasctructural, DNA ladder and TUNEL labeling study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:16-23.

- Koba S, Paulson KG, Nagase K, et al. Diagnostic biopsy does not commonly induce intratumoral CD8 T cell infiltration in Merkel cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e41465.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare, rapidly growing, aggressive neoplasm with a generally poor prognosis. The cells of origin are highly anaplastic and share structural and immunohistochemical features with various neuroectodermally derived cells. Although Merkel cells, which are slow-acting cutaneous mechanoreceptors located in the basal layer of the epidermis, and MCC share immunohistochemical and ultrastructural features, there is limited evidence of a direct histogenetic relationship between the two.1,2 Additionally, some extracutaneous neuroendocrine tumors have features similar to MCC; therefore, although it may be more accurate and perhaps more practical to describe these lesions as primary neuroendocrine carcinomas of the skin, the term MCC is more commonly used both in the literature and in clinical practice.1,2

Merkel cell carcinoma typically presents in the head and neck region in white patients older than 70 years of age and in the immunocompromised population.3-6 The mean age of diagnosis is 76 years for women and 74 years for men.7 The incidence of MCC in the United States tripled over a 15-year period, and there are approximately 1500 new cases of MCC diagnosed each year, making it about 40 times less common than melanoma.8 The 5-year survival rate for patients without lymph node involvement is 75%, whereas the 5-year survival rate for patients with distant metastases is 25%.9

Merkel cell carcinoma is thought to develop through 1 of 2 distinct pathways. In a virally mediated pathway, which represents at least 80% of cases, the Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCV) monoclonally integrates into the host genome and promotes oncogenesis via altered p53 and retinoblastoma protein expression.10-12 The remainder of cases are believed to develop via a nonvirally mediated pathway in which genetic anomalies, immune status, and environmental factors influence oncogenesis.10-13

Due to the similarity between MCC and metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasms, especially small-cell lung carcinomas, immunohistochemistry is important in making the diagnosis. Cytokeratin 20 and neuron-specific enolase positivity and thyroid transcription factor 1 negativity are the most useful markers in identifying MCC.

Regression of MCC is a very rare and poorly understood event. A 2010 review of the literature described 22 cases of spontaneous regression.14 We report a rare case of rapid and complete regression of MCC following punch biopsy in a 96-year-old woman.

Case Report

A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained at a follow-up visit 4 weeks later (12 weeks after the reported onset of the lesion). Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed a small-cell neoplasm with stippled nuclei and scant cytoplasm forming a nested and somewhat trabecular pattern. Mitotic activity, apoptosis, and nuclear molding also were present (Figure 2). The tumor cells were positive for cytokeratin 20 with a dotlike, paranuclear pattern (Figure 3). Staining for CAM 5.2 also was positive. Cytokeratin 5/6, human melanoma black 45, and leukocyte common antigen were negative. The immunophenotyping of the lymphocytic response to the tumor showed that the majority of intratumoral lymphocytes were CD8 positive (Figure 4). CD4-positive lymphocytes were predominantly seen at the periphery of the tumor nests without tumor infiltration (Figure 5). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of MCC was made. The patient’s family declined treatment based on her advanced age and current health status, which included advanced dementia.

Two weeks after the punch biopsy, the lesion had noticeably decreased in size and lost its dome-shaped appearance. Within 8 weeks after biopsy (20 weeks since the lesion first appeared), the lesion had completely resolved (Figure 6). The patient was lost to follow-up months later, but no recurrence of the lesion was reported.

Comment

Spontaneous regression is not unique to MCC, as this phenomenon also has been reported in keratoacanthoma, lymphoma, basal cell carcinoma, and melanoma.15 Complete spontaneous regression is defined as occurring in the absence of therapy that is intended to have a treatment effect.15,16 Spontaneous regression is estimated to occur in malignant neoplasms at a rate of 1 case per 60,000 to 100,000 (approximately 0.0013% of all malignant neoplasms).17 Considering the reported prevalence of MCC and the number of cases that have been known to regress, the estimated incidence of complete spontaneous regression may be as high as 1.5%.14 Though spontaneous regression of MCC is more prevalent than expected, it still is considered a rare phenomenon. A 2010 review of the literature yielded 22 cases of complete spontaneous regression of MCC.14 No recurrences have been observed; however, follow-up was relatively short in some cases.

In a unique report by Bertolotti et al,18 a patient with MCC on the nasal tip presented 4 weeks after biopsy with complete spontaneous regression of the tumor, which was associated with bilateral cervical lymph node involvement as noted by hypermetabolic uptake on positron emission tomography scanning. The patient underwent radiation therapy and was disease free at 12 months’ follow-up.18

Complete spontaneous regression has been described in MCC patients with local disease, regional recurrences, and metastatic disease.19 In

The histopathologic features observed in our case, specifically intratumoral CD8-positive cytotoxic lymphocytes and peritumoral CD4-positive cells, were similar to the findings in other reported cases. In one series of 2 cases, the one case showed scar tissue with a moderate, predominantly T-lymphocytic infiltrate and no tumor cells, and the second showed cellular proliferation in the deep dermis with dense lymphocytic infiltrates primarily composed of CD3-positive T cells.14 Other studies of regression of both localized and metastatic MCC demonstrated infiltration by CD4-positive, CD8-positive, and CD3-positive lymphocytes and foamy macrophages.21-23

The discovery of the MCV was one of the most important advances in elucidating the pathogenesis of MCC.10,24-26 Merkel cell polyomavirus DNA has been detected in a majority of MCC cases.25,27 Viral integration has been shown to take place early, prior to tumor clonal expansion.10 Importantly, not all cases of MCC show MCV infection, and MCV infection is not exclusive to MCC.28 Merkel cell polyomavirus is considered to be part of the normal human flora, and asymptomatic infection is quite common.29 It has been identified in 80% of adults older than 50 years of age and, interestingly, in 35% of children by 13 years of age or younger.30,31 It remains unclear what role the presence of MCV plays in determining MCC prognosis. Several reports have demonstrated lower disease-specific mortality associated with MCV-positive MCC.32-35 In contrast, Schrama et al36 correlated the MCV status of 174 MCC tumors and found no difference in clinical behavior or prognosis between MCV-positive and MCV-negative MCCs.

Immunosuppression also may play a role in the development of MCC.5,25 There is increased prevalence of MCC in the human immunodeficiency virus–positive population, as well as in organ-transplant recipients and patients with leukemia. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia seems to be the most frequent neoplasia associated with development of MCC.37

The mechanism of MCC regression remains unclear, but many investigators emphasize the importance of T-cell–mediated immunity.16,21-23,38,39 Apoptosis also has been shown to play an important role.40 Our case showed tumor-infiltrating CD8-positive lymphocytes and CD4-positive lymphocytes present predominantly at the periphery of the tumor, with close proximity to the tumor nests but with no tumor infiltration (Figure 3). This distribution was consistently present in multiple sections of the tumor. These findings are consistent with prior reports of both CD4-positive and CD8-positive T lymphocytes associated with MCC regression. Our findings confirm that immune response may play an important role in spontaneous regression of MCC.

There is much speculation regarding the initial biopsy of an MCC lesion (or other traumatic event) and its role in tumor regression. Koba et al41 examined the effect of biopsy on CD8-positive lymphocytic infiltration of MCC tumor cells and found that biopsy does not commonly alter intratumoral CD8-positive infiltration. These findings suggest trauma does not directly induce immunologic recognition of this cancer.

Conclusion

We report a case of complete spontaneous regression of a localized MCC following a punch biopsy. The histopathology showed a brisk T-lymphocyte response with intratumoral CD8-positive cytotoxic lymphocytes and peritumoral CD4-positive cells. The age and clinical profile of our patient as well as the clinicopathologic characteristics of the tumor regression are similar to other reported cases. Further research is needed to elucidate the mechanism of MCC regression, and a better understanding of this fascinating phenomenon could help in development of new immunotherapeutic approaches.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare, rapidly growing, aggressive neoplasm with a generally poor prognosis. The cells of origin are highly anaplastic and share structural and immunohistochemical features with various neuroectodermally derived cells. Although Merkel cells, which are slow-acting cutaneous mechanoreceptors located in the basal layer of the epidermis, and MCC share immunohistochemical and ultrastructural features, there is limited evidence of a direct histogenetic relationship between the two.1,2 Additionally, some extracutaneous neuroendocrine tumors have features similar to MCC; therefore, although it may be more accurate and perhaps more practical to describe these lesions as primary neuroendocrine carcinomas of the skin, the term MCC is more commonly used both in the literature and in clinical practice.1,2

Merkel cell carcinoma typically presents in the head and neck region in white patients older than 70 years of age and in the immunocompromised population.3-6 The mean age of diagnosis is 76 years for women and 74 years for men.7 The incidence of MCC in the United States tripled over a 15-year period, and there are approximately 1500 new cases of MCC diagnosed each year, making it about 40 times less common than melanoma.8 The 5-year survival rate for patients without lymph node involvement is 75%, whereas the 5-year survival rate for patients with distant metastases is 25%.9

Merkel cell carcinoma is thought to develop through 1 of 2 distinct pathways. In a virally mediated pathway, which represents at least 80% of cases, the Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCV) monoclonally integrates into the host genome and promotes oncogenesis via altered p53 and retinoblastoma protein expression.10-12 The remainder of cases are believed to develop via a nonvirally mediated pathway in which genetic anomalies, immune status, and environmental factors influence oncogenesis.10-13

Due to the similarity between MCC and metastatic neuroendocrine neoplasms, especially small-cell lung carcinomas, immunohistochemistry is important in making the diagnosis. Cytokeratin 20 and neuron-specific enolase positivity and thyroid transcription factor 1 negativity are the most useful markers in identifying MCC.

Regression of MCC is a very rare and poorly understood event. A 2010 review of the literature described 22 cases of spontaneous regression.14 We report a rare case of rapid and complete regression of MCC following punch biopsy in a 96-year-old woman.

Case Report

A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained at a follow-up visit 4 weeks later (12 weeks after the reported onset of the lesion). Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed a small-cell neoplasm with stippled nuclei and scant cytoplasm forming a nested and somewhat trabecular pattern. Mitotic activity, apoptosis, and nuclear molding also were present (Figure 2). The tumor cells were positive for cytokeratin 20 with a dotlike, paranuclear pattern (Figure 3). Staining for CAM 5.2 also was positive. Cytokeratin 5/6, human melanoma black 45, and leukocyte common antigen were negative. The immunophenotyping of the lymphocytic response to the tumor showed that the majority of intratumoral lymphocytes were CD8 positive (Figure 4). CD4-positive lymphocytes were predominantly seen at the periphery of the tumor nests without tumor infiltration (Figure 5). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of MCC was made. The patient’s family declined treatment based on her advanced age and current health status, which included advanced dementia.

Two weeks after the punch biopsy, the lesion had noticeably decreased in size and lost its dome-shaped appearance. Within 8 weeks after biopsy (20 weeks since the lesion first appeared), the lesion had completely resolved (Figure 6). The patient was lost to follow-up months later, but no recurrence of the lesion was reported.

Comment

Spontaneous regression is not unique to MCC, as this phenomenon also has been reported in keratoacanthoma, lymphoma, basal cell carcinoma, and melanoma.15 Complete spontaneous regression is defined as occurring in the absence of therapy that is intended to have a treatment effect.15,16 Spontaneous regression is estimated to occur in malignant neoplasms at a rate of 1 case per 60,000 to 100,000 (approximately 0.0013% of all malignant neoplasms).17 Considering the reported prevalence of MCC and the number of cases that have been known to regress, the estimated incidence of complete spontaneous regression may be as high as 1.5%.14 Though spontaneous regression of MCC is more prevalent than expected, it still is considered a rare phenomenon. A 2010 review of the literature yielded 22 cases of complete spontaneous regression of MCC.14 No recurrences have been observed; however, follow-up was relatively short in some cases.

In a unique report by Bertolotti et al,18 a patient with MCC on the nasal tip presented 4 weeks after biopsy with complete spontaneous regression of the tumor, which was associated with bilateral cervical lymph node involvement as noted by hypermetabolic uptake on positron emission tomography scanning. The patient underwent radiation therapy and was disease free at 12 months’ follow-up.18

Complete spontaneous regression has been described in MCC patients with local disease, regional recurrences, and metastatic disease.19 In

The histopathologic features observed in our case, specifically intratumoral CD8-positive cytotoxic lymphocytes and peritumoral CD4-positive cells, were similar to the findings in other reported cases. In one series of 2 cases, the one case showed scar tissue with a moderate, predominantly T-lymphocytic infiltrate and no tumor cells, and the second showed cellular proliferation in the deep dermis with dense lymphocytic infiltrates primarily composed of CD3-positive T cells.14 Other studies of regression of both localized and metastatic MCC demonstrated infiltration by CD4-positive, CD8-positive, and CD3-positive lymphocytes and foamy macrophages.21-23

The discovery of the MCV was one of the most important advances in elucidating the pathogenesis of MCC.10,24-26 Merkel cell polyomavirus DNA has been detected in a majority of MCC cases.25,27 Viral integration has been shown to take place early, prior to tumor clonal expansion.10 Importantly, not all cases of MCC show MCV infection, and MCV infection is not exclusive to MCC.28 Merkel cell polyomavirus is considered to be part of the normal human flora, and asymptomatic infection is quite common.29 It has been identified in 80% of adults older than 50 years of age and, interestingly, in 35% of children by 13 years of age or younger.30,31 It remains unclear what role the presence of MCV plays in determining MCC prognosis. Several reports have demonstrated lower disease-specific mortality associated with MCV-positive MCC.32-35 In contrast, Schrama et al36 correlated the MCV status of 174 MCC tumors and found no difference in clinical behavior or prognosis between MCV-positive and MCV-negative MCCs.

Immunosuppression also may play a role in the development of MCC.5,25 There is increased prevalence of MCC in the human immunodeficiency virus–positive population, as well as in organ-transplant recipients and patients with leukemia. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia seems to be the most frequent neoplasia associated with development of MCC.37

The mechanism of MCC regression remains unclear, but many investigators emphasize the importance of T-cell–mediated immunity.16,21-23,38,39 Apoptosis also has been shown to play an important role.40 Our case showed tumor-infiltrating CD8-positive lymphocytes and CD4-positive lymphocytes present predominantly at the periphery of the tumor, with close proximity to the tumor nests but with no tumor infiltration (Figure 3). This distribution was consistently present in multiple sections of the tumor. These findings are consistent with prior reports of both CD4-positive and CD8-positive T lymphocytes associated with MCC regression. Our findings confirm that immune response may play an important role in spontaneous regression of MCC.

There is much speculation regarding the initial biopsy of an MCC lesion (or other traumatic event) and its role in tumor regression. Koba et al41 examined the effect of biopsy on CD8-positive lymphocytic infiltration of MCC tumor cells and found that biopsy does not commonly alter intratumoral CD8-positive infiltration. These findings suggest trauma does not directly induce immunologic recognition of this cancer.

Conclusion

We report a case of complete spontaneous regression of a localized MCC following a punch biopsy. The histopathology showed a brisk T-lymphocyte response with intratumoral CD8-positive cytotoxic lymphocytes and peritumoral CD4-positive cells. The age and clinical profile of our patient as well as the clinicopathologic characteristics of the tumor regression are similar to other reported cases. Further research is needed to elucidate the mechanism of MCC regression, and a better understanding of this fascinating phenomenon could help in development of new immunotherapeutic approaches.

- Sibley RK, Dehner LP, Rosai J. Primary neuroendocrine (Merkel cell?) carcinoma of the skin. I. a clinicopathologic and ultrastructural study of 43 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:95-108.

- Sibley RK, Dahl D. Primary neuroendocrine (Merkel cell?) carcinoma of the skin. II. an immunocytochemical study of 21 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:109-116.

- Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

- Penn I, First MR. Merkel’s cell carcinoma in organ recipients: report of 41 cases. Transplantation. 1999;68:1717-1721.

- Gooptu C, Woolloons A, Ross J, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma arising after therapeutic immunosuppression. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:637-641.

- Plunkett TA, Harris AJ, Ogg CS, et al. The treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma and its association with immunosuppression. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:345-346.

- Calder KB, Smoller BR. New insights into Merkel cell carcinoma. Adv Anat Pathol. 2010;17:155-161.

- Hodgson NC. Merkel cell carcinoma: changing incidence trends. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:1-4.

- Agelli M, Clegg LX. Epidemiology of primary Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:832-841.

- Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, et al. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096-1100.

- Amber K, McLeod MP, Nouri K. The Merkel cell polyomavirus and its involvement in Merkel cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:232-238.

- Decaprio JA. Does detection of Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma provide prognostic information? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:905-907.

- Popp S, Waltering S, Herbst C, et al. UV-B-type mutations and chromosomal imbalances indicate common pathways for the development of Merkel and skin squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:352-360.

- Ciudad C, Avilés JA, Alfageme F, et al. Spontaneous regression in Merkel cell carcinoma: report of two cases with description of dermoscopic features and review of literature. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:687-693.

- O’Rourke MGE, Bell JR. Merkel cell tumor with spontaneous regression. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1986;12:994-997.

- Connelly TJ, Cribier B, Brown TJ, et al. Complete spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma: a review of 10 reported cases. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:853-856.

- Cole WH. Efforts to explain spontaneous regression of cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1981;17:201-209.

- Bertolotti A, Conte H, Francois L, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: complete clinical remission associated with disease progression. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:501-502.

- Pang C, Sharma D, Sankar T. Spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature [published online November 13, 2014]. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;7C:104-108.

- Richetta AG, Mancini M, Torroni A, et al. Total spontaneous regression of advanced Merkel cell carcinoma after biopsy: review and a new case. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:815-822.

- Vesely MJ, Murray DJ, Neligan PC, et al. Complete spontaneous regression in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61:165-171.

- Kayashima K, Ono T, Johno M, et al. Spontaneous regression in Merkel cell (neuroendocrine) carcinoma of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:550-553.

- Maruo K, Kayashima KI, Ono T. Regressing Merkel cell carcinoma-a case showing replacement of tumour cells by foamy cells. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:1184-1189.

- Duncavage E, Zehnbauer B, Pfeifer J. Prevalence of Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:516-521.

- Kassem A, Schopflin A, Diaz C, et al. Frequent detection of Merkel cell polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinomas and identification of unique deletion in the VP1 gene. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5009-5013.

- Becker J, Schrama D, Houben R. Merkel cell carcinoma. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:1-8.

- Haitz KA, Rady PL, Nguyen HP, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus DNA detection in a patient with Merkel cell carcinoma and multiple other skin cancers. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:442-444.

- Andres C, Puchta U, Sander CA, et al. Prevalence of Merkel cell polyomavirus DNA in cutaneous lymphomas, pseudolymphomas, and inflammatory skin diseases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:593-598.

- Showalter RM, Pastrana DV, Pumphrey KA, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus and two previously unknown polyomaviruses are chronically shed from human skin. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:509-515.

- Tolstov YL, Pastrana DV, Feng H, et al. Human Merkel cell polyomavirus infection II. MCV is a common human infection that can be detected by conformational capsid epitope immunoassays. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1250-1256.

- Chen T, Hedman L, Mattila PS, et al. Serological evidence of Merkel cell polyomavirus primary infections in childhood. J Clin Virol. 2011;50:125-129.

- Laude HC, Jonchère B, Maubec E, et al. Distinct Merkel cell polyomavirus molecular features in tumour and non tumour specimens from patients with Merkel cell carcinoma. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001076.

- Waltari M, Sihto H, Kukko H, et al. Association of Merkel cell polyomavirus infection with tumor p53, KIT, stem cell factor, PDGFR-alpha and survival in Merkel cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:619-628.

- Sihto H, Kukko H, Koljonen V, et al. Clinical factors associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus infection in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:938-945.

- Paulson KG, Lemos BD, Feng B, et al. Array-CGH reveals recurrent genomic changes in Merkel cell carcinoma including amplification of L-Myc. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1547-1555.

- Schrama D, Peitsch WK, Zapatka M, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus status is not associated with clinical course of Merkel cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1631-1638.

- Tadmor T, Aviv A, Polliack A. Merkel cell carcinoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia and other lymphoproliferative disorders: an old bond with possible new viral ties. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:250-256.

- Wooff J, Trites JR, Walsh NM, et al. Complete spontaneous regression of metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:614-617.

- Turk TO, Smoljan I, Nacinovic A, et al. Spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:7270.

- Mori Y, Tanaka K, Cui CY, et al. A study of apoptosis in Merkel cell carcinoma. an immunohistochemical, ultrasctructural, DNA ladder and TUNEL labeling study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:16-23.

- Koba S, Paulson KG, Nagase K, et al. Diagnostic biopsy does not commonly induce intratumoral CD8 T cell infiltration in Merkel cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e41465.

- Sibley RK, Dehner LP, Rosai J. Primary neuroendocrine (Merkel cell?) carcinoma of the skin. I. a clinicopathologic and ultrastructural study of 43 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:95-108.

- Sibley RK, Dahl D. Primary neuroendocrine (Merkel cell?) carcinoma of the skin. II. an immunocytochemical study of 21 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1985;9:109-116.

- Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

- Penn I, First MR. Merkel’s cell carcinoma in organ recipients: report of 41 cases. Transplantation. 1999;68:1717-1721.

- Gooptu C, Woolloons A, Ross J, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma arising after therapeutic immunosuppression. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:637-641.

- Plunkett TA, Harris AJ, Ogg CS, et al. The treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma and its association with immunosuppression. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:345-346.

- Calder KB, Smoller BR. New insights into Merkel cell carcinoma. Adv Anat Pathol. 2010;17:155-161.

- Hodgson NC. Merkel cell carcinoma: changing incidence trends. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:1-4.

- Agelli M, Clegg LX. Epidemiology of primary Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:832-841.

- Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, et al. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science. 2008;319:1096-1100.

- Amber K, McLeod MP, Nouri K. The Merkel cell polyomavirus and its involvement in Merkel cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:232-238.

- Decaprio JA. Does detection of Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma provide prognostic information? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:905-907.

- Popp S, Waltering S, Herbst C, et al. UV-B-type mutations and chromosomal imbalances indicate common pathways for the development of Merkel and skin squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:352-360.

- Ciudad C, Avilés JA, Alfageme F, et al. Spontaneous regression in Merkel cell carcinoma: report of two cases with description of dermoscopic features and review of literature. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:687-693.

- O’Rourke MGE, Bell JR. Merkel cell tumor with spontaneous regression. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1986;12:994-997.

- Connelly TJ, Cribier B, Brown TJ, et al. Complete spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma: a review of 10 reported cases. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:853-856.

- Cole WH. Efforts to explain spontaneous regression of cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1981;17:201-209.

- Bertolotti A, Conte H, Francois L, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: complete clinical remission associated with disease progression. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:501-502.

- Pang C, Sharma D, Sankar T. Spontaneous regression of Merkel cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature [published online November 13, 2014]. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;7C:104-108.

- Richetta AG, Mancini M, Torroni A, et al. Total spontaneous regression of advanced Merkel cell carcinoma after biopsy: review and a new case. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:815-822.

- Vesely MJ, Murray DJ, Neligan PC, et al. Complete spontaneous regression in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61:165-171.

- Kayashima K, Ono T, Johno M, et al. Spontaneous regression in Merkel cell (neuroendocrine) carcinoma of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:550-553.

- Maruo K, Kayashima KI, Ono T. Regressing Merkel cell carcinoma-a case showing replacement of tumour cells by foamy cells. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:1184-1189.

- Duncavage E, Zehnbauer B, Pfeifer J. Prevalence of Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:516-521.

- Kassem A, Schopflin A, Diaz C, et al. Frequent detection of Merkel cell polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinomas and identification of unique deletion in the VP1 gene. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5009-5013.

- Becker J, Schrama D, Houben R. Merkel cell carcinoma. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:1-8.

- Haitz KA, Rady PL, Nguyen HP, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus DNA detection in a patient with Merkel cell carcinoma and multiple other skin cancers. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:442-444.

- Andres C, Puchta U, Sander CA, et al. Prevalence of Merkel cell polyomavirus DNA in cutaneous lymphomas, pseudolymphomas, and inflammatory skin diseases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:593-598.

- Showalter RM, Pastrana DV, Pumphrey KA, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus and two previously unknown polyomaviruses are chronically shed from human skin. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:509-515.

- Tolstov YL, Pastrana DV, Feng H, et al. Human Merkel cell polyomavirus infection II. MCV is a common human infection that can be detected by conformational capsid epitope immunoassays. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1250-1256.

- Chen T, Hedman L, Mattila PS, et al. Serological evidence of Merkel cell polyomavirus primary infections in childhood. J Clin Virol. 2011;50:125-129.

- Laude HC, Jonchère B, Maubec E, et al. Distinct Merkel cell polyomavirus molecular features in tumour and non tumour specimens from patients with Merkel cell carcinoma. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001076.

- Waltari M, Sihto H, Kukko H, et al. Association of Merkel cell polyomavirus infection with tumor p53, KIT, stem cell factor, PDGFR-alpha and survival in Merkel cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:619-628.

- Sihto H, Kukko H, Koljonen V, et al. Clinical factors associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus infection in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:938-945.

- Paulson KG, Lemos BD, Feng B, et al. Array-CGH reveals recurrent genomic changes in Merkel cell carcinoma including amplification of L-Myc. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1547-1555.

- Schrama D, Peitsch WK, Zapatka M, et al. Merkel cell polyomavirus status is not associated with clinical course of Merkel cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1631-1638.

- Tadmor T, Aviv A, Polliack A. Merkel cell carcinoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia and other lymphoproliferative disorders: an old bond with possible new viral ties. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:250-256.