User login

Characterization of Blood-borne Pathogen Exposures During Dermatologic Procedures: The Mayo Clinic Experience

Dermatology providers are at an increased risk for blood-borne pathogen (BBP) exposures during procedures in clinical practice.1-3 Current data regarding the characterization of these exposures are limited. Prior studies are based on surveys that result in low response rates and potential for selection bias. Donnelly et al1 reported a 26% response rate in a national survey-based study evaluating BBP exposures in resident physicians, fellows, and practicing dermatologists, with 85% of respondents reporting at least 1 injury. Similarly, Goulart et al2 reported a 35% response rate in a survey evaluating sharps injuries in residents and medical students, with 85% reporting a sharps injury. In addition, there are conflicting data regarding characteristics of these exposures, including common implicated instruments and procedures.1-3 Prior studies also have not evaluated exposures in all members of dermatologic staff, including resident physicians, practicing dermatologists, and ancillary staff.

To make appropriate quality improvements in dermatologic procedures, a more comprehensive understanding of BBP exposures is needed. We conducted a retrospective review of BBP incidence reports to identify the incidence of BBP events among all dermatologic staff, including resident physicians, practicing dermatologists, and ancillary staff. We further investigated the type of exposure, the type of procedure associated with each exposure, anatomic locations of exposures, and instruments involved in each exposure.

Methods

Data on BBP exposures in the dermatology departments were obtained from the occupational health departments at each of 3 Mayo Clinic sites—Scottsdale, Arizona; Jacksonville, Florida; and Rochester, Minnesota—from March 2010 through January 2021. The institutional review board at Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona, granted approval of this study (IRB #20-012625). A retrospective review of each exposure was conducted to identify the incidence of BBP exposures. Occupational BBP exposure was defined as

Statistical Analysis—Variables were summarized using counts and percentages. The 3 most common categories for each variable were then compared among occupational groups using the Fisher exact test. All other categories were grouped for analysis purposes. Medical staff were categorized into 3 occupational groups: practicing dermatologists; resident physicians; and ancillary staff, including nurse/medical assistants, physician assistants, and clinical laboratory technologists. All analyses were 2 sided and considered statistically significant at P<.05. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

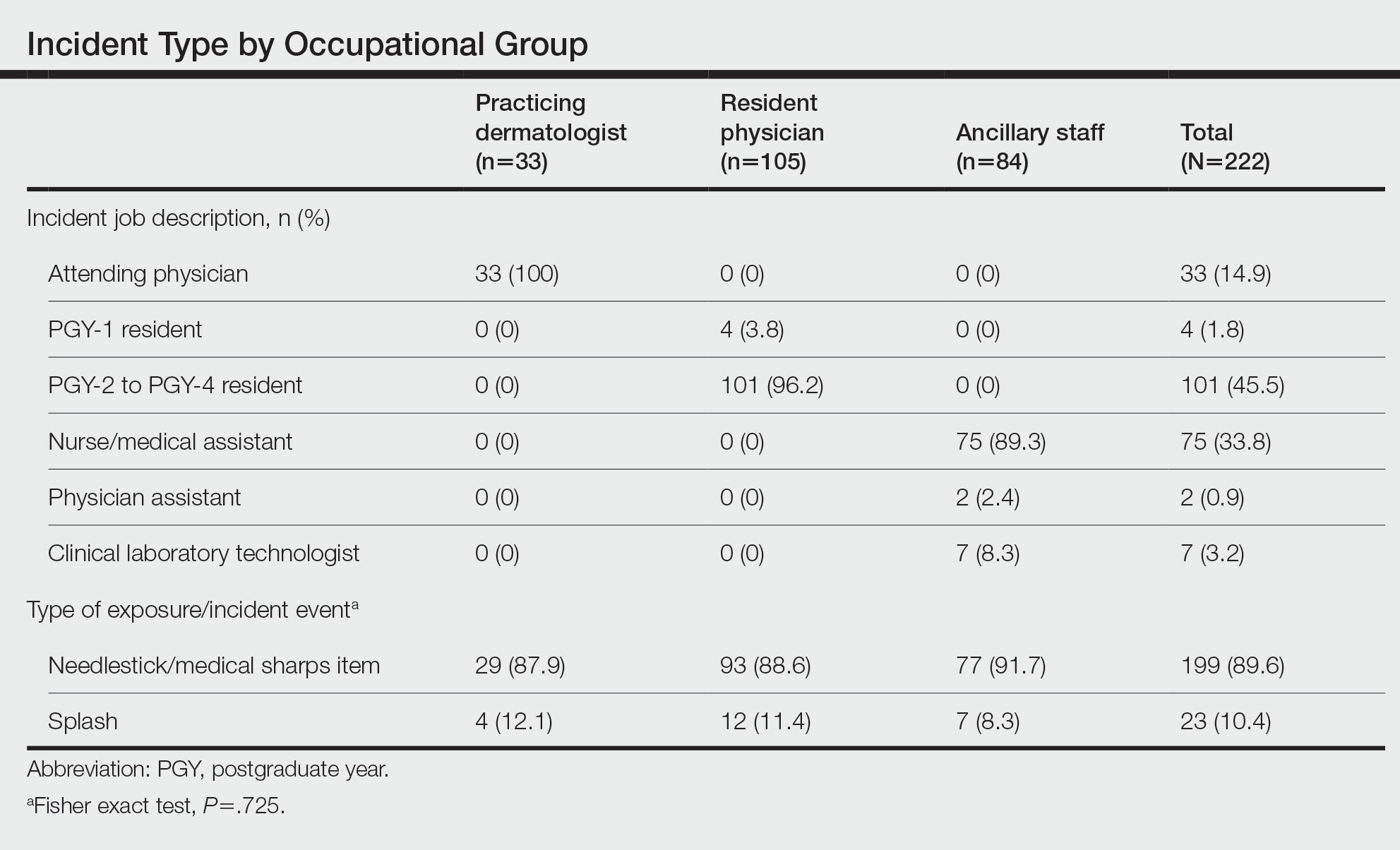

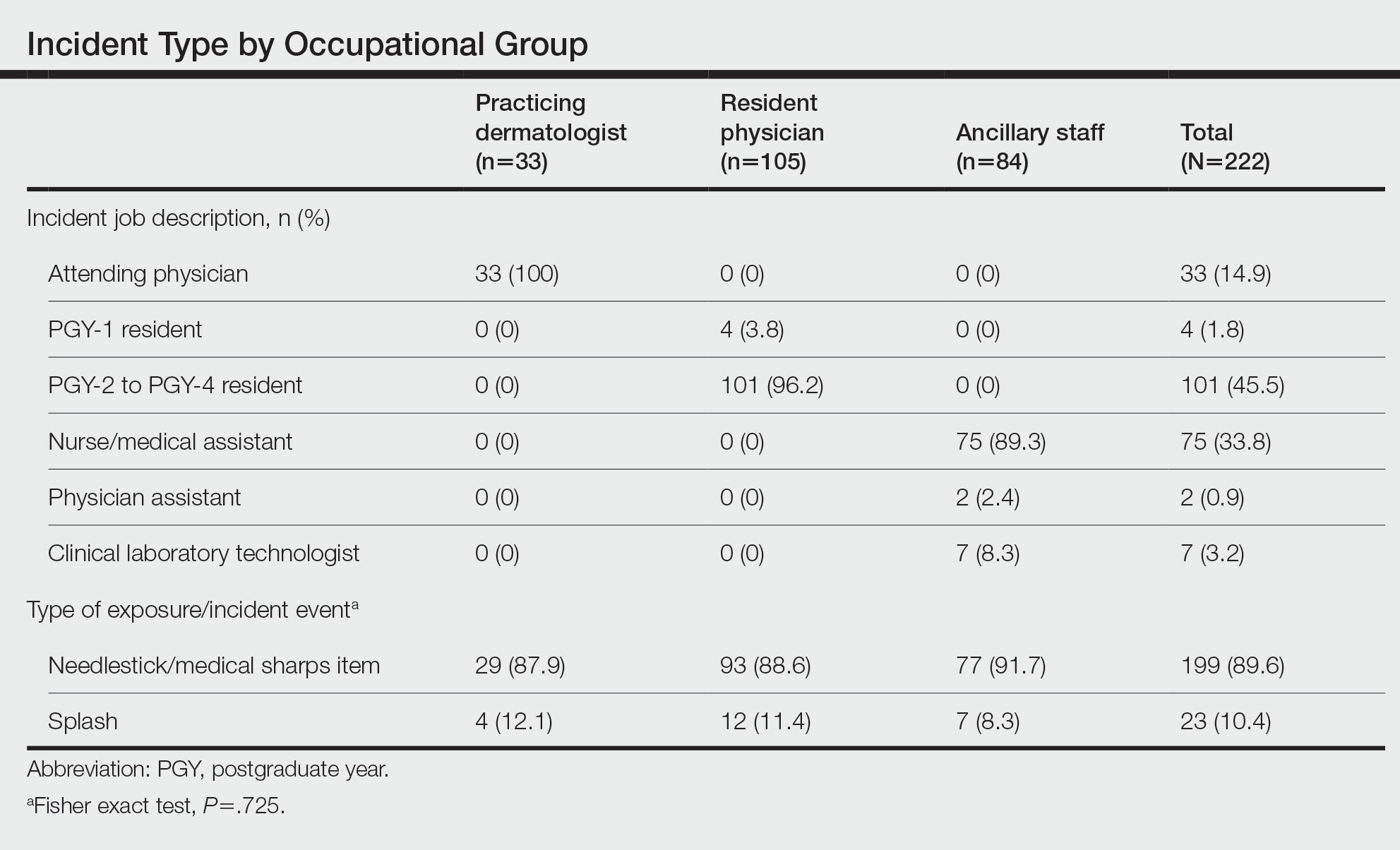

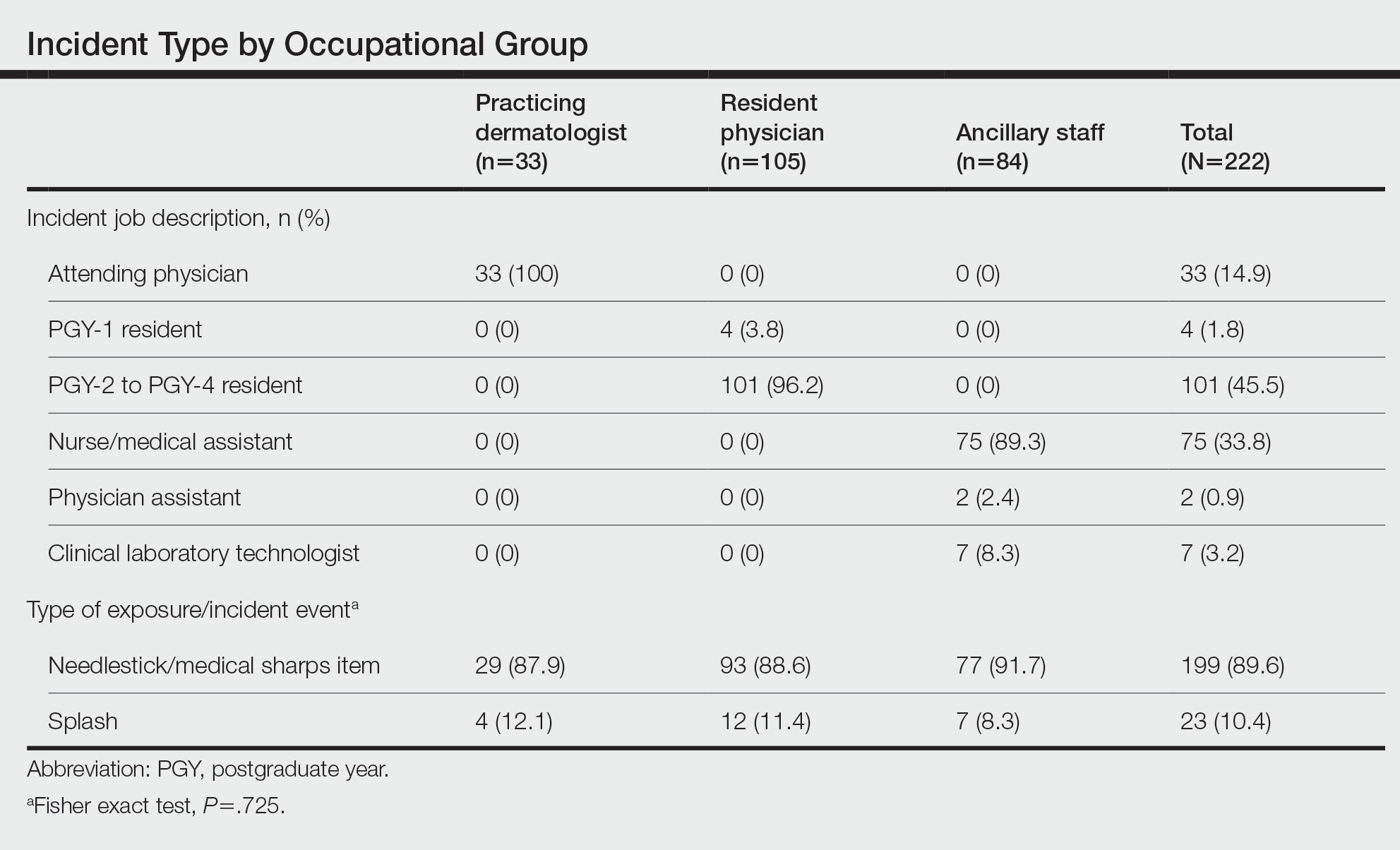

Type of Exposure—A total of 222 BBP exposures were identified through the trisite retrospective review from March 2010 through January 2021. One hundred ninety-nine (89.6%) of 222 exposures were attributed to needlesticks and medical sharps, while 23 (10.4%) of 222 exposures were attributed to splash incidents (Table).

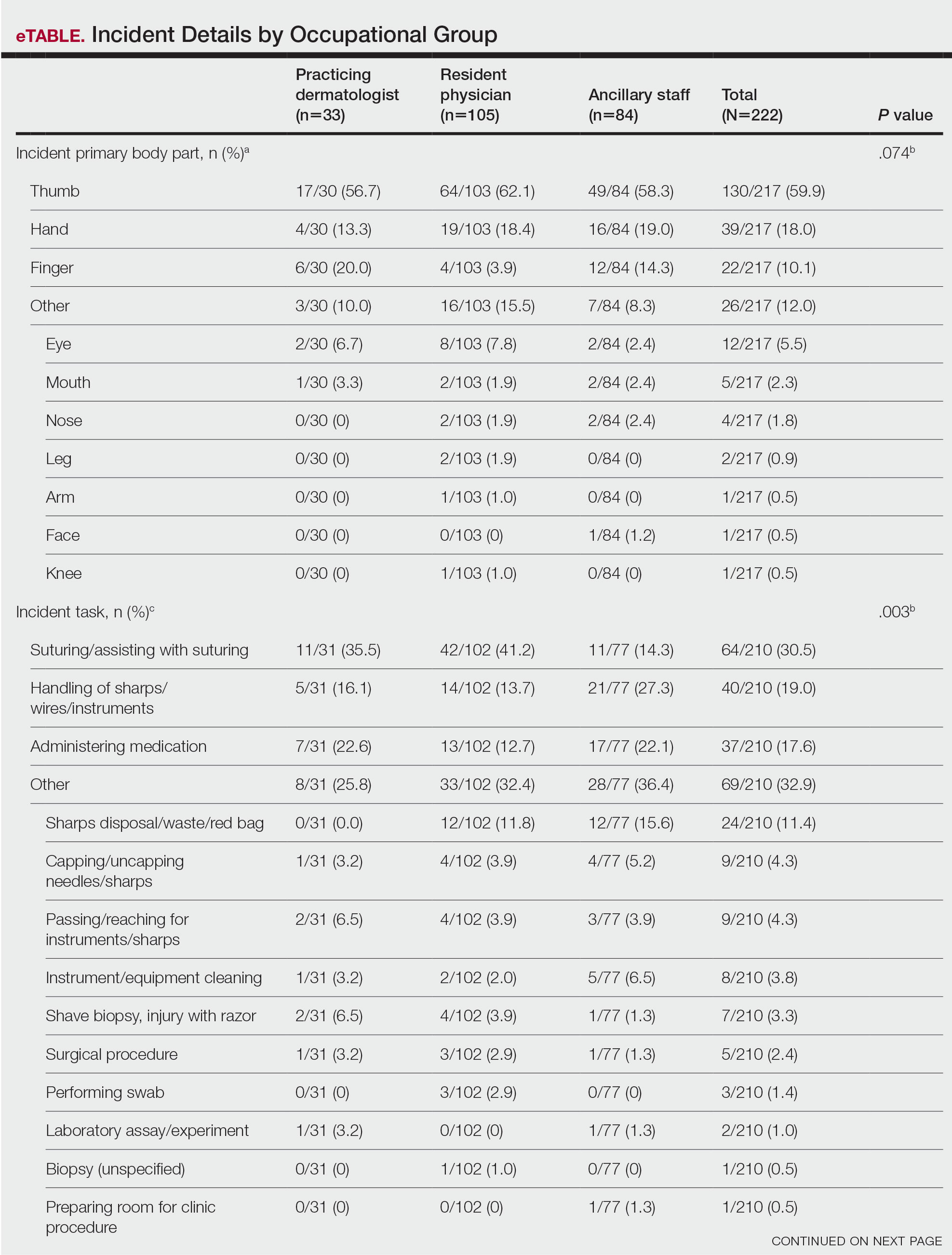

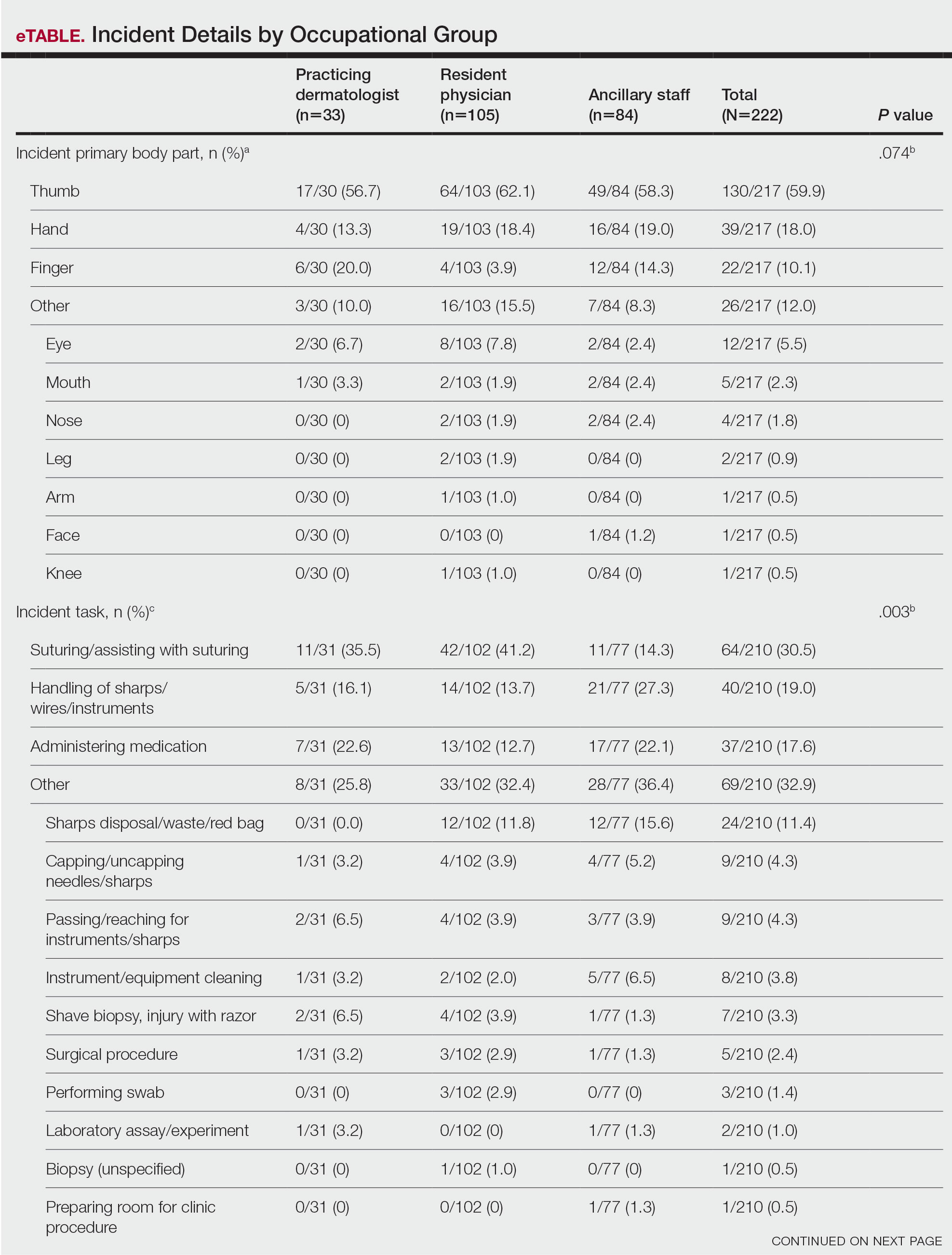

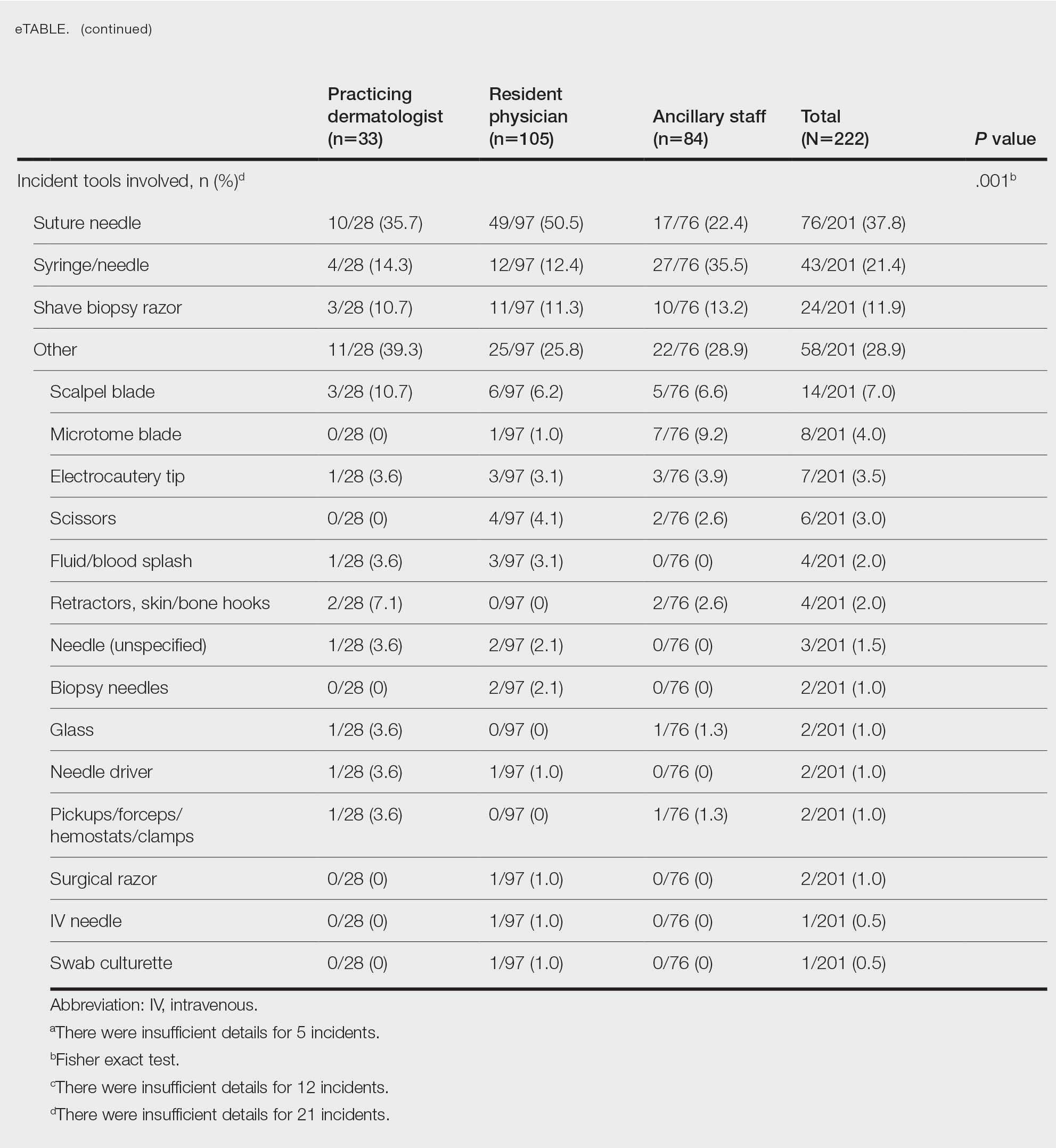

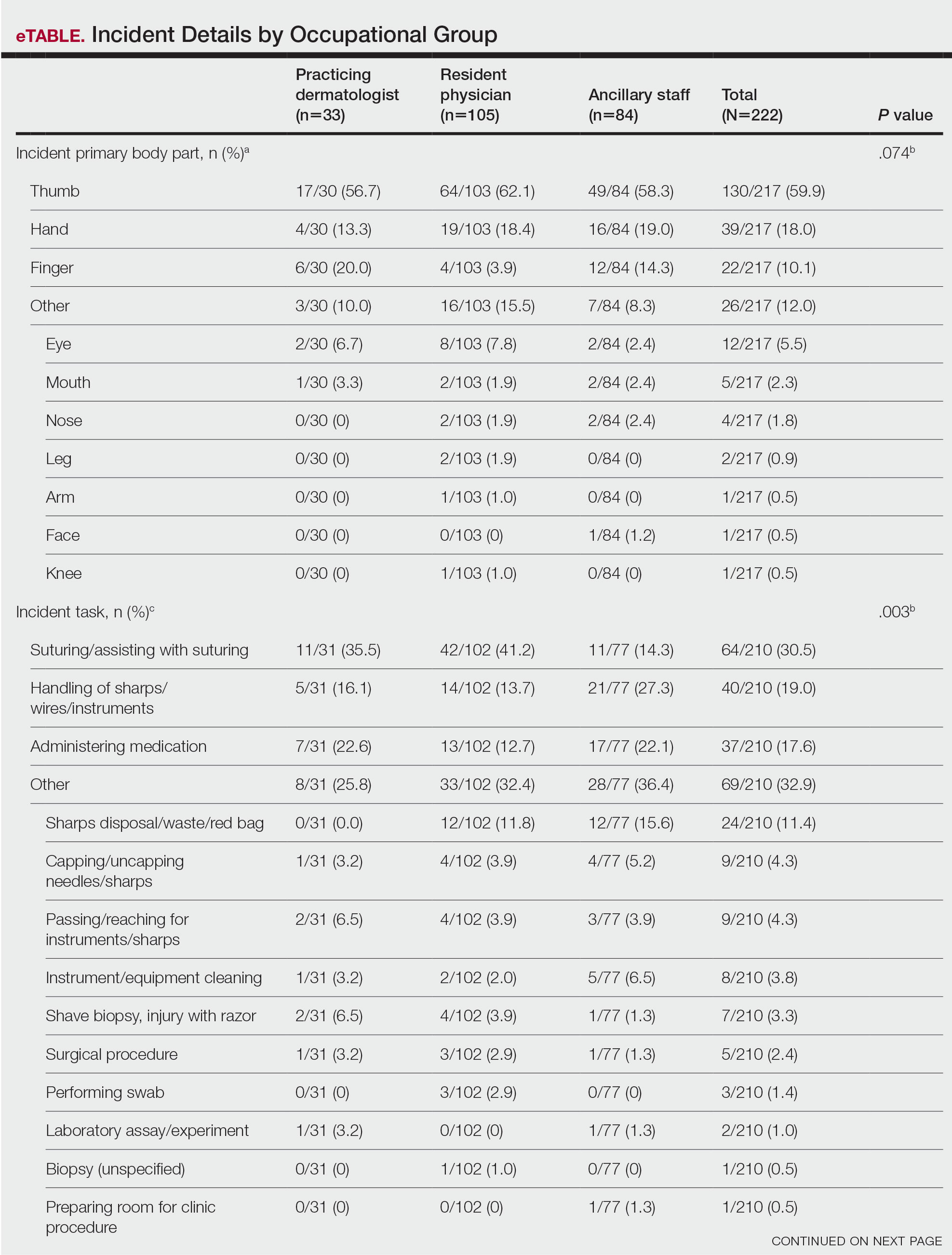

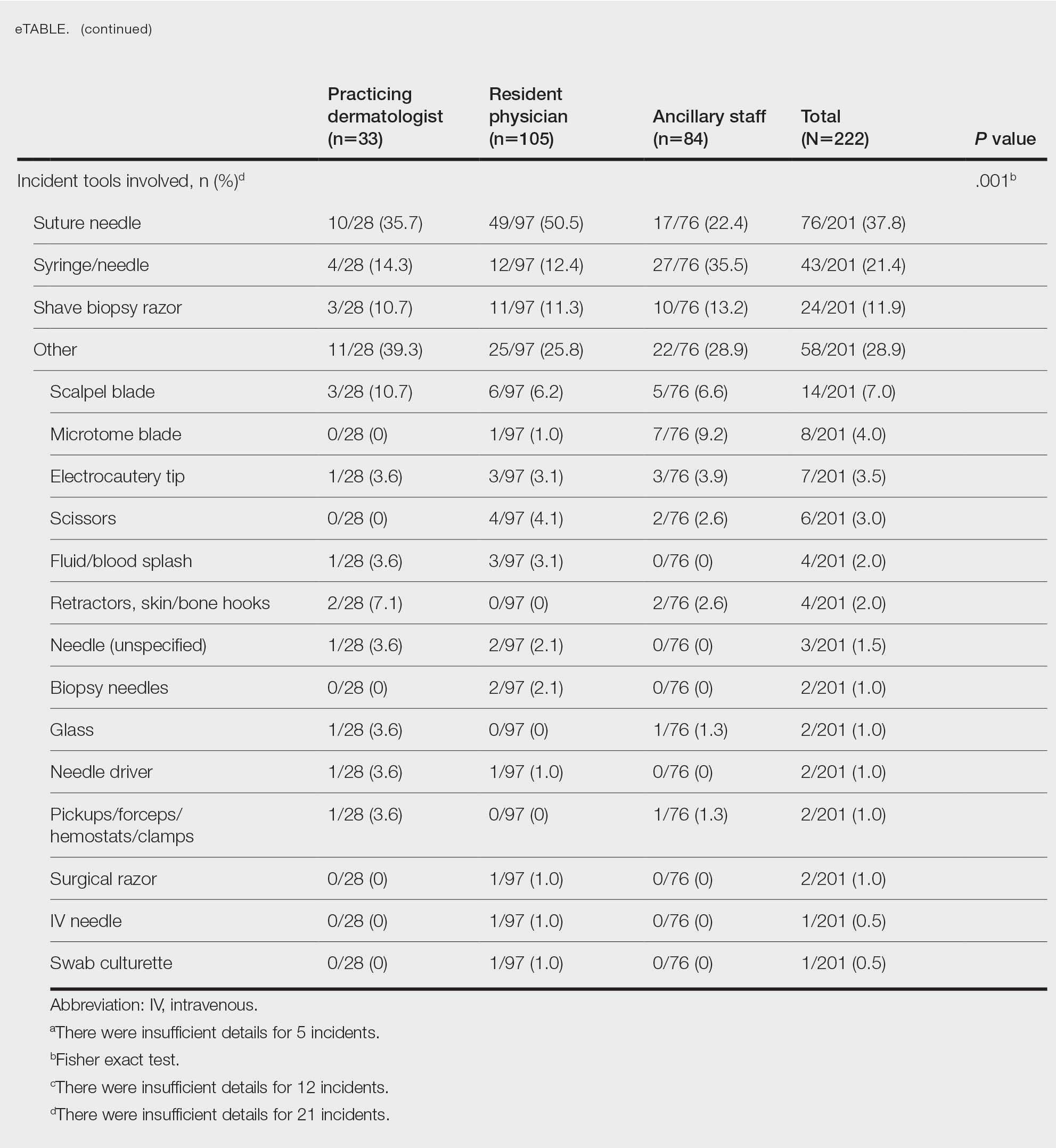

Anatomic Sites Affected—The anatomic location most frequently involved was the thumb (130/217 events [59.9%]), followed by the hand (39/217 events [18.0%]) and finger (22/217 events [10.1%]). The arm, face, and knee were affected with the lowest frequency, with only 1 event reported at each anatomic site (0.5%)(eTable). Five incidents were excluded from the analysis of anatomic location because of insufficient details of events.

Incident Tasks and Tools—Most BBP exposures occurred during suturing or assisting with suturing (64/210 events [30.5%]), followed by handling of sharps, wires, or instruments (40/210 events [19.0%]) and medication administration (37/210 events [17.6%])(eTable). Twelve incidents were excluded from the analysis of implicated tasks because of insufficient details of events.

The tools involved in exposure events with the greatest prevalence included the suture needle (76/201 events [37.8%]), injection syringe/needle (43/201 events [21.4%]), and shave biopsy razor (24/201 events [11.9%])(eTable). Twenty-one incidents were excluded from the analysis of implicated instruments because of insufficient details of events.

Providers Affected by BBP Exposures—Resident physicians experienced the greatest number of BBP exposures (105/222 events [47.3%]), followed by ancillary providers (84/222 events [37.8%]) and practicing dermatologists (33/222 events [14.9%]). All occupational groups experienced more BBP exposures through needlesticks/medical sharps compared with splash incidents (resident physicians, 88.6%; ancillary staff, 91.7%; practicing dermatologists, 87.9%; P=.725)(Table).

Among resident physicians, practicing dermatologists, and ancillary staff, the most frequent site of injury was the thumb. Suturing/assisting with suturing was the most common task leading to injury, and the suture needle was the most common instrument of injury for both resident physicians and practicing dermatologists. Handling of sharps, wires, or instruments was the most common task leading to injury for ancillary staff, and the injection syringe/needle was the most common instrument of injury in this cohort.

Resident physicians experienced the lowest rate of BBP exposures during administration of medications (12.7%; P=.003). Ancillary staff experienced the highest rate of BBP exposures with an injection needle (35.5%; P=.001). There were no statistically significant differences among occupational groups for the anatomic location of injury (P=.074)(eTable).

Comment

In the year 2000, the annual global incidence of occupational BBP exposures among health care workers worldwide for hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and HIV was estimated at 2.1 million, 926,000, and 327,000, respectively. Most of these exposures were due to sharps injuries.4 Dermatologists are particularly at risk for BBP exposures given their reliance on frequent procedures in practice. During an 11-year period, 222 BBP exposures were documented in the dermatology departments at 3 Mayo Clinic institutions. Most exposures were due to needlestick/sharps across all occupational groups compared with splash injuries. Prior survey studies confirm that sharps injuries are frequently implicated, with 75% to 94% of residents and practicing dermatologists reporting at least 1 sharps injury.1

Among occupational groups, resident physicians had the highest rate of BBP exposures, followed by nurse/medical assistants and practicing dermatologists, which may be secondary to lack of training or experience. Data from other surgical fields, including general surgery, support that resident physicians have the highest rate of sharps injuries.5 In a survey study (N=452), 51% of residents reported that extra training in safe techniques would be beneficial.2 Safety training may be beneficial in reducing the incidence of BBP exposures in residency programs.

The most common implicated task in resident physicians and practicing dermatologists was suturing or assisting with suturing, and the most common implicated instrument was the suture needle. Prior studies showed conflicting data regarding common implicated tasks and instruments in this cohort.1,2 The task of suturing and the suture needle also were the most implicated means of injury among other surgical specialties.6 Ancillary staff experienced most BBP exposures during handling of sharps, wires, or instruments, as well as the use of an injection needle. The designation of tasks among dermatologic staff likely explains the difference among occupational groups. This new information may provide the opportunity to improve safety measures among all members of the dermatologic team.

Limitations—There are several limitations to this study. This retrospective review was conducted at a single health system at 3 institutions. Hence, similar safety protocols likely were in place across all sites, which may reduce the generalizability of the results. In addition, there is risk of nonreporting bias among staff, as only documented incidence reports were evaluated. Prior studies demonstrated a nonreporting prevalence of 33% to 64% among dermatology staff.1-3 We also did not evaluate whether injuries resulted in BBP exposure or transmission. The rates of postexposure prophylaxis also were not studied. This information was not available for review because of concerns for privacy. Demographic features, such as gender or years of training, also were not evaluated.

Conclusion

This study provides additional insight on the incidence of BBP exposures in dermatology, as well as the implicated tasks, instruments, and anatomic locations of injury. Studies show that implementing formal education regarding the risks of BBP exposure may result in reduction of sharps injuries.7 Formal education in residency programs may be needed in the field of dermatology to reduce BBP exposures. Quality improvement measures should focus on identified risk factors among occupational groups to reduce BBP exposures in the workplace.

- Donnelly AF, Chang Y-HH, Nemeth-Ochoa SA. Sharps injuries and reporting practices of U.S. dermatologists [published online November 14, 2013]. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1813-1821.

- Goulart J, Oliveria S, Levitt J. Safety during dermatologic procedures and surgeries: a survey of resident injuries and prevention strategies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:648-650.

- Ken K, Golda N. Contaminated sharps injuries: a survey among dermatology residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1786-1788.

- Pruss-Ustun A, Rapiti E, Hutin Y. Estimation of global burden of disease attributable to contaminated sharps injuries among health-care workers. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48:482-490.

- Choi L, Torres R, Syed S, et al. Sharps and needlestick injuries among medical students, surgical residents, faculty, and operating room staff at a single academic institution. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:131-136.

- Bakaeen F, Awad S, Albo D, et al. Epidemiology of exposure to blood borne pathogens on a surgical service. Am J Surg. 2006;192:E18-E21.

- Li WJ, Zhang M, Shi CL, et al. Study on intervention of bloodborne pathogen exposure in a general hospital [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi. 2017;35:34-41.

Dermatology providers are at an increased risk for blood-borne pathogen (BBP) exposures during procedures in clinical practice.1-3 Current data regarding the characterization of these exposures are limited. Prior studies are based on surveys that result in low response rates and potential for selection bias. Donnelly et al1 reported a 26% response rate in a national survey-based study evaluating BBP exposures in resident physicians, fellows, and practicing dermatologists, with 85% of respondents reporting at least 1 injury. Similarly, Goulart et al2 reported a 35% response rate in a survey evaluating sharps injuries in residents and medical students, with 85% reporting a sharps injury. In addition, there are conflicting data regarding characteristics of these exposures, including common implicated instruments and procedures.1-3 Prior studies also have not evaluated exposures in all members of dermatologic staff, including resident physicians, practicing dermatologists, and ancillary staff.

To make appropriate quality improvements in dermatologic procedures, a more comprehensive understanding of BBP exposures is needed. We conducted a retrospective review of BBP incidence reports to identify the incidence of BBP events among all dermatologic staff, including resident physicians, practicing dermatologists, and ancillary staff. We further investigated the type of exposure, the type of procedure associated with each exposure, anatomic locations of exposures, and instruments involved in each exposure.

Methods

Data on BBP exposures in the dermatology departments were obtained from the occupational health departments at each of 3 Mayo Clinic sites—Scottsdale, Arizona; Jacksonville, Florida; and Rochester, Minnesota—from March 2010 through January 2021. The institutional review board at Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona, granted approval of this study (IRB #20-012625). A retrospective review of each exposure was conducted to identify the incidence of BBP exposures. Occupational BBP exposure was defined as

Statistical Analysis—Variables were summarized using counts and percentages. The 3 most common categories for each variable were then compared among occupational groups using the Fisher exact test. All other categories were grouped for analysis purposes. Medical staff were categorized into 3 occupational groups: practicing dermatologists; resident physicians; and ancillary staff, including nurse/medical assistants, physician assistants, and clinical laboratory technologists. All analyses were 2 sided and considered statistically significant at P<.05. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Type of Exposure—A total of 222 BBP exposures were identified through the trisite retrospective review from March 2010 through January 2021. One hundred ninety-nine (89.6%) of 222 exposures were attributed to needlesticks and medical sharps, while 23 (10.4%) of 222 exposures were attributed to splash incidents (Table).

Anatomic Sites Affected—The anatomic location most frequently involved was the thumb (130/217 events [59.9%]), followed by the hand (39/217 events [18.0%]) and finger (22/217 events [10.1%]). The arm, face, and knee were affected with the lowest frequency, with only 1 event reported at each anatomic site (0.5%)(eTable). Five incidents were excluded from the analysis of anatomic location because of insufficient details of events.

Incident Tasks and Tools—Most BBP exposures occurred during suturing or assisting with suturing (64/210 events [30.5%]), followed by handling of sharps, wires, or instruments (40/210 events [19.0%]) and medication administration (37/210 events [17.6%])(eTable). Twelve incidents were excluded from the analysis of implicated tasks because of insufficient details of events.

The tools involved in exposure events with the greatest prevalence included the suture needle (76/201 events [37.8%]), injection syringe/needle (43/201 events [21.4%]), and shave biopsy razor (24/201 events [11.9%])(eTable). Twenty-one incidents were excluded from the analysis of implicated instruments because of insufficient details of events.

Providers Affected by BBP Exposures—Resident physicians experienced the greatest number of BBP exposures (105/222 events [47.3%]), followed by ancillary providers (84/222 events [37.8%]) and practicing dermatologists (33/222 events [14.9%]). All occupational groups experienced more BBP exposures through needlesticks/medical sharps compared with splash incidents (resident physicians, 88.6%; ancillary staff, 91.7%; practicing dermatologists, 87.9%; P=.725)(Table).

Among resident physicians, practicing dermatologists, and ancillary staff, the most frequent site of injury was the thumb. Suturing/assisting with suturing was the most common task leading to injury, and the suture needle was the most common instrument of injury for both resident physicians and practicing dermatologists. Handling of sharps, wires, or instruments was the most common task leading to injury for ancillary staff, and the injection syringe/needle was the most common instrument of injury in this cohort.

Resident physicians experienced the lowest rate of BBP exposures during administration of medications (12.7%; P=.003). Ancillary staff experienced the highest rate of BBP exposures with an injection needle (35.5%; P=.001). There were no statistically significant differences among occupational groups for the anatomic location of injury (P=.074)(eTable).

Comment

In the year 2000, the annual global incidence of occupational BBP exposures among health care workers worldwide for hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and HIV was estimated at 2.1 million, 926,000, and 327,000, respectively. Most of these exposures were due to sharps injuries.4 Dermatologists are particularly at risk for BBP exposures given their reliance on frequent procedures in practice. During an 11-year period, 222 BBP exposures were documented in the dermatology departments at 3 Mayo Clinic institutions. Most exposures were due to needlestick/sharps across all occupational groups compared with splash injuries. Prior survey studies confirm that sharps injuries are frequently implicated, with 75% to 94% of residents and practicing dermatologists reporting at least 1 sharps injury.1

Among occupational groups, resident physicians had the highest rate of BBP exposures, followed by nurse/medical assistants and practicing dermatologists, which may be secondary to lack of training or experience. Data from other surgical fields, including general surgery, support that resident physicians have the highest rate of sharps injuries.5 In a survey study (N=452), 51% of residents reported that extra training in safe techniques would be beneficial.2 Safety training may be beneficial in reducing the incidence of BBP exposures in residency programs.

The most common implicated task in resident physicians and practicing dermatologists was suturing or assisting with suturing, and the most common implicated instrument was the suture needle. Prior studies showed conflicting data regarding common implicated tasks and instruments in this cohort.1,2 The task of suturing and the suture needle also were the most implicated means of injury among other surgical specialties.6 Ancillary staff experienced most BBP exposures during handling of sharps, wires, or instruments, as well as the use of an injection needle. The designation of tasks among dermatologic staff likely explains the difference among occupational groups. This new information may provide the opportunity to improve safety measures among all members of the dermatologic team.

Limitations—There are several limitations to this study. This retrospective review was conducted at a single health system at 3 institutions. Hence, similar safety protocols likely were in place across all sites, which may reduce the generalizability of the results. In addition, there is risk of nonreporting bias among staff, as only documented incidence reports were evaluated. Prior studies demonstrated a nonreporting prevalence of 33% to 64% among dermatology staff.1-3 We also did not evaluate whether injuries resulted in BBP exposure or transmission. The rates of postexposure prophylaxis also were not studied. This information was not available for review because of concerns for privacy. Demographic features, such as gender or years of training, also were not evaluated.

Conclusion

This study provides additional insight on the incidence of BBP exposures in dermatology, as well as the implicated tasks, instruments, and anatomic locations of injury. Studies show that implementing formal education regarding the risks of BBP exposure may result in reduction of sharps injuries.7 Formal education in residency programs may be needed in the field of dermatology to reduce BBP exposures. Quality improvement measures should focus on identified risk factors among occupational groups to reduce BBP exposures in the workplace.

Dermatology providers are at an increased risk for blood-borne pathogen (BBP) exposures during procedures in clinical practice.1-3 Current data regarding the characterization of these exposures are limited. Prior studies are based on surveys that result in low response rates and potential for selection bias. Donnelly et al1 reported a 26% response rate in a national survey-based study evaluating BBP exposures in resident physicians, fellows, and practicing dermatologists, with 85% of respondents reporting at least 1 injury. Similarly, Goulart et al2 reported a 35% response rate in a survey evaluating sharps injuries in residents and medical students, with 85% reporting a sharps injury. In addition, there are conflicting data regarding characteristics of these exposures, including common implicated instruments and procedures.1-3 Prior studies also have not evaluated exposures in all members of dermatologic staff, including resident physicians, practicing dermatologists, and ancillary staff.

To make appropriate quality improvements in dermatologic procedures, a more comprehensive understanding of BBP exposures is needed. We conducted a retrospective review of BBP incidence reports to identify the incidence of BBP events among all dermatologic staff, including resident physicians, practicing dermatologists, and ancillary staff. We further investigated the type of exposure, the type of procedure associated with each exposure, anatomic locations of exposures, and instruments involved in each exposure.

Methods

Data on BBP exposures in the dermatology departments were obtained from the occupational health departments at each of 3 Mayo Clinic sites—Scottsdale, Arizona; Jacksonville, Florida; and Rochester, Minnesota—from March 2010 through January 2021. The institutional review board at Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona, granted approval of this study (IRB #20-012625). A retrospective review of each exposure was conducted to identify the incidence of BBP exposures. Occupational BBP exposure was defined as

Statistical Analysis—Variables were summarized using counts and percentages. The 3 most common categories for each variable were then compared among occupational groups using the Fisher exact test. All other categories were grouped for analysis purposes. Medical staff were categorized into 3 occupational groups: practicing dermatologists; resident physicians; and ancillary staff, including nurse/medical assistants, physician assistants, and clinical laboratory technologists. All analyses were 2 sided and considered statistically significant at P<.05. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Type of Exposure—A total of 222 BBP exposures were identified through the trisite retrospective review from March 2010 through January 2021. One hundred ninety-nine (89.6%) of 222 exposures were attributed to needlesticks and medical sharps, while 23 (10.4%) of 222 exposures were attributed to splash incidents (Table).

Anatomic Sites Affected—The anatomic location most frequently involved was the thumb (130/217 events [59.9%]), followed by the hand (39/217 events [18.0%]) and finger (22/217 events [10.1%]). The arm, face, and knee were affected with the lowest frequency, with only 1 event reported at each anatomic site (0.5%)(eTable). Five incidents were excluded from the analysis of anatomic location because of insufficient details of events.

Incident Tasks and Tools—Most BBP exposures occurred during suturing or assisting with suturing (64/210 events [30.5%]), followed by handling of sharps, wires, or instruments (40/210 events [19.0%]) and medication administration (37/210 events [17.6%])(eTable). Twelve incidents were excluded from the analysis of implicated tasks because of insufficient details of events.

The tools involved in exposure events with the greatest prevalence included the suture needle (76/201 events [37.8%]), injection syringe/needle (43/201 events [21.4%]), and shave biopsy razor (24/201 events [11.9%])(eTable). Twenty-one incidents were excluded from the analysis of implicated instruments because of insufficient details of events.

Providers Affected by BBP Exposures—Resident physicians experienced the greatest number of BBP exposures (105/222 events [47.3%]), followed by ancillary providers (84/222 events [37.8%]) and practicing dermatologists (33/222 events [14.9%]). All occupational groups experienced more BBP exposures through needlesticks/medical sharps compared with splash incidents (resident physicians, 88.6%; ancillary staff, 91.7%; practicing dermatologists, 87.9%; P=.725)(Table).

Among resident physicians, practicing dermatologists, and ancillary staff, the most frequent site of injury was the thumb. Suturing/assisting with suturing was the most common task leading to injury, and the suture needle was the most common instrument of injury for both resident physicians and practicing dermatologists. Handling of sharps, wires, or instruments was the most common task leading to injury for ancillary staff, and the injection syringe/needle was the most common instrument of injury in this cohort.

Resident physicians experienced the lowest rate of BBP exposures during administration of medications (12.7%; P=.003). Ancillary staff experienced the highest rate of BBP exposures with an injection needle (35.5%; P=.001). There were no statistically significant differences among occupational groups for the anatomic location of injury (P=.074)(eTable).

Comment

In the year 2000, the annual global incidence of occupational BBP exposures among health care workers worldwide for hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and HIV was estimated at 2.1 million, 926,000, and 327,000, respectively. Most of these exposures were due to sharps injuries.4 Dermatologists are particularly at risk for BBP exposures given their reliance on frequent procedures in practice. During an 11-year period, 222 BBP exposures were documented in the dermatology departments at 3 Mayo Clinic institutions. Most exposures were due to needlestick/sharps across all occupational groups compared with splash injuries. Prior survey studies confirm that sharps injuries are frequently implicated, with 75% to 94% of residents and practicing dermatologists reporting at least 1 sharps injury.1

Among occupational groups, resident physicians had the highest rate of BBP exposures, followed by nurse/medical assistants and practicing dermatologists, which may be secondary to lack of training or experience. Data from other surgical fields, including general surgery, support that resident physicians have the highest rate of sharps injuries.5 In a survey study (N=452), 51% of residents reported that extra training in safe techniques would be beneficial.2 Safety training may be beneficial in reducing the incidence of BBP exposures in residency programs.

The most common implicated task in resident physicians and practicing dermatologists was suturing or assisting with suturing, and the most common implicated instrument was the suture needle. Prior studies showed conflicting data regarding common implicated tasks and instruments in this cohort.1,2 The task of suturing and the suture needle also were the most implicated means of injury among other surgical specialties.6 Ancillary staff experienced most BBP exposures during handling of sharps, wires, or instruments, as well as the use of an injection needle. The designation of tasks among dermatologic staff likely explains the difference among occupational groups. This new information may provide the opportunity to improve safety measures among all members of the dermatologic team.

Limitations—There are several limitations to this study. This retrospective review was conducted at a single health system at 3 institutions. Hence, similar safety protocols likely were in place across all sites, which may reduce the generalizability of the results. In addition, there is risk of nonreporting bias among staff, as only documented incidence reports were evaluated. Prior studies demonstrated a nonreporting prevalence of 33% to 64% among dermatology staff.1-3 We also did not evaluate whether injuries resulted in BBP exposure or transmission. The rates of postexposure prophylaxis also were not studied. This information was not available for review because of concerns for privacy. Demographic features, such as gender or years of training, also were not evaluated.

Conclusion

This study provides additional insight on the incidence of BBP exposures in dermatology, as well as the implicated tasks, instruments, and anatomic locations of injury. Studies show that implementing formal education regarding the risks of BBP exposure may result in reduction of sharps injuries.7 Formal education in residency programs may be needed in the field of dermatology to reduce BBP exposures. Quality improvement measures should focus on identified risk factors among occupational groups to reduce BBP exposures in the workplace.

- Donnelly AF, Chang Y-HH, Nemeth-Ochoa SA. Sharps injuries and reporting practices of U.S. dermatologists [published online November 14, 2013]. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1813-1821.

- Goulart J, Oliveria S, Levitt J. Safety during dermatologic procedures and surgeries: a survey of resident injuries and prevention strategies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:648-650.

- Ken K, Golda N. Contaminated sharps injuries: a survey among dermatology residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1786-1788.

- Pruss-Ustun A, Rapiti E, Hutin Y. Estimation of global burden of disease attributable to contaminated sharps injuries among health-care workers. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48:482-490.

- Choi L, Torres R, Syed S, et al. Sharps and needlestick injuries among medical students, surgical residents, faculty, and operating room staff at a single academic institution. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:131-136.

- Bakaeen F, Awad S, Albo D, et al. Epidemiology of exposure to blood borne pathogens on a surgical service. Am J Surg. 2006;192:E18-E21.

- Li WJ, Zhang M, Shi CL, et al. Study on intervention of bloodborne pathogen exposure in a general hospital [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi. 2017;35:34-41.

- Donnelly AF, Chang Y-HH, Nemeth-Ochoa SA. Sharps injuries and reporting practices of U.S. dermatologists [published online November 14, 2013]. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1813-1821.

- Goulart J, Oliveria S, Levitt J. Safety during dermatologic procedures and surgeries: a survey of resident injuries and prevention strategies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:648-650.

- Ken K, Golda N. Contaminated sharps injuries: a survey among dermatology residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1786-1788.

- Pruss-Ustun A, Rapiti E, Hutin Y. Estimation of global burden of disease attributable to contaminated sharps injuries among health-care workers. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48:482-490.

- Choi L, Torres R, Syed S, et al. Sharps and needlestick injuries among medical students, surgical residents, faculty, and operating room staff at a single academic institution. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:131-136.

- Bakaeen F, Awad S, Albo D, et al. Epidemiology of exposure to blood borne pathogens on a surgical service. Am J Surg. 2006;192:E18-E21.

- Li WJ, Zhang M, Shi CL, et al. Study on intervention of bloodborne pathogen exposure in a general hospital [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi. 2017;35:34-41.

Practice Points

- Most blood-borne pathogen (BBP) exposures in dermatologic staff occur due to medical sharps as opposed to splash incidents.

- The most common implicated task in resident physicians and practicing dermatologists is suturing or assisting with suturing, and the most commonly associated instrument is the suture needle. In contrast, ancillary staff experience most BBP exposures during handling of sharps, wires, or instruments, and the injection syringe/needle is the most common instrument of injury.

- Quality improvement measures are needed in prevention of BBP exposures and should focus on identified risk factors among occupational groups in the workplace.

Characteristics of Matched vs Nonmatched Dermatology Applicants

Dermatology residency continues to be one of the most competitive specialties, with a match rate of 84.7% for US allopathic seniors in the 2019-2020 academic year.1 In the 2019-2020 cycle, dermatology applicants were tied with plastic surgery for the highest median US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score compared with other specialties, which suggests that the top medical students are applying, yet only approximately 5 of 6 students are matching.

Factors that have been cited with successful dermatology matching include USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 Clinical Knowledge (CK) scores,2 research accomplishments,3 letters of recommendation,4 medical school performance, personal statement, grades in required clerkships, and volunteer/extracurricular experiences, among others.5

The National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) publishes data each year regarding different academic factors—USMLE scores; number of abstracts, presentations, and papers; work, volunteer, and research experiences—and compares the mean between matched and nonmatched applicants.1 However, the USMLE does not report any demographic information of the applicants and the implication it has for matching. Additionally, the number of couples participating in the couples match continues to increase each year. In the 2019-2020 cycle, 1224 couples participated in the couples match.1 However, NRMP reports only limited data regarding the couples match, and it is not specialty specific.

We aimed to determine the characteristics of matched vs nonmatched dermatology applicants. Secondarily, we aimed to determine any differences among demographics regarding matching rates, academic performance, and research publications. We also aimed to characterize the strategy and outcomes of applicants that couples matched.

Materials and Methods

The Mayo Clinic institutional review board deemed this study exempt. All applicants who applied to Mayo Clinic dermatology residency in Scottsdale, Arizona, during the 2018-2019 cycle were emailed an initial survey (N=475) before Match Day that obtained demographic information, geographic information, gap-year information, USMLE Step 1 score, publications, medical school grades, number of away rotations, and number of interviews. A follow-up survey gathering match data and couples matching data was sent to the applicants who completed the first survey on Match Day. The survey was repeated for the 2019-2020 cycle. In the second survey, Step 2 CK data were obtained. The survey was sent to 629 applicants who applied to Mayo Clinic dermatology residencies in Arizona, Minnesota, and Florida to include a broader group of applicants. For publications, applicants were asked to count only published or accepted manuscripts, not abstracts, posters, conference presentations, or submitted manuscripts. Applicants who did not respond to the second survey (match data) were not included in that part of the analysis. One survey was excluded because of implausible answers (eg, scores outside of range for USMLE Step scores).

Statistical Analysis—For statistical analyses, the applicants from both applications cycles were combined. Descriptive statistics were reported in the form of mean, median, or counts (percentages), as applicable. Means were compared using 2-sided t tests. Group comparisons were examined using χ2 tests for categorical variables. Statistical analyses were performed using the BlueSky Statistics version 6.30. P<.05 was considered significant.

Results

In 2019, a total of 149 applicants completed the initial survey (31.4% response rate), and 112 completed the follow-up survey (75.2% response rate). In 2020, a total of 142 applicants completed the initial survey (22.6% response rate), and 124 completed the follow-up survey (87.3% response rate). Combining the 2 years, after removing 1 survey with implausible answers, there were 290 respondents from the initial survey and 235 from the follow-up survey. The median (SD) age for the total applicants over both years was 27 (3.0) years, and 180 applicants were female (61.9%).

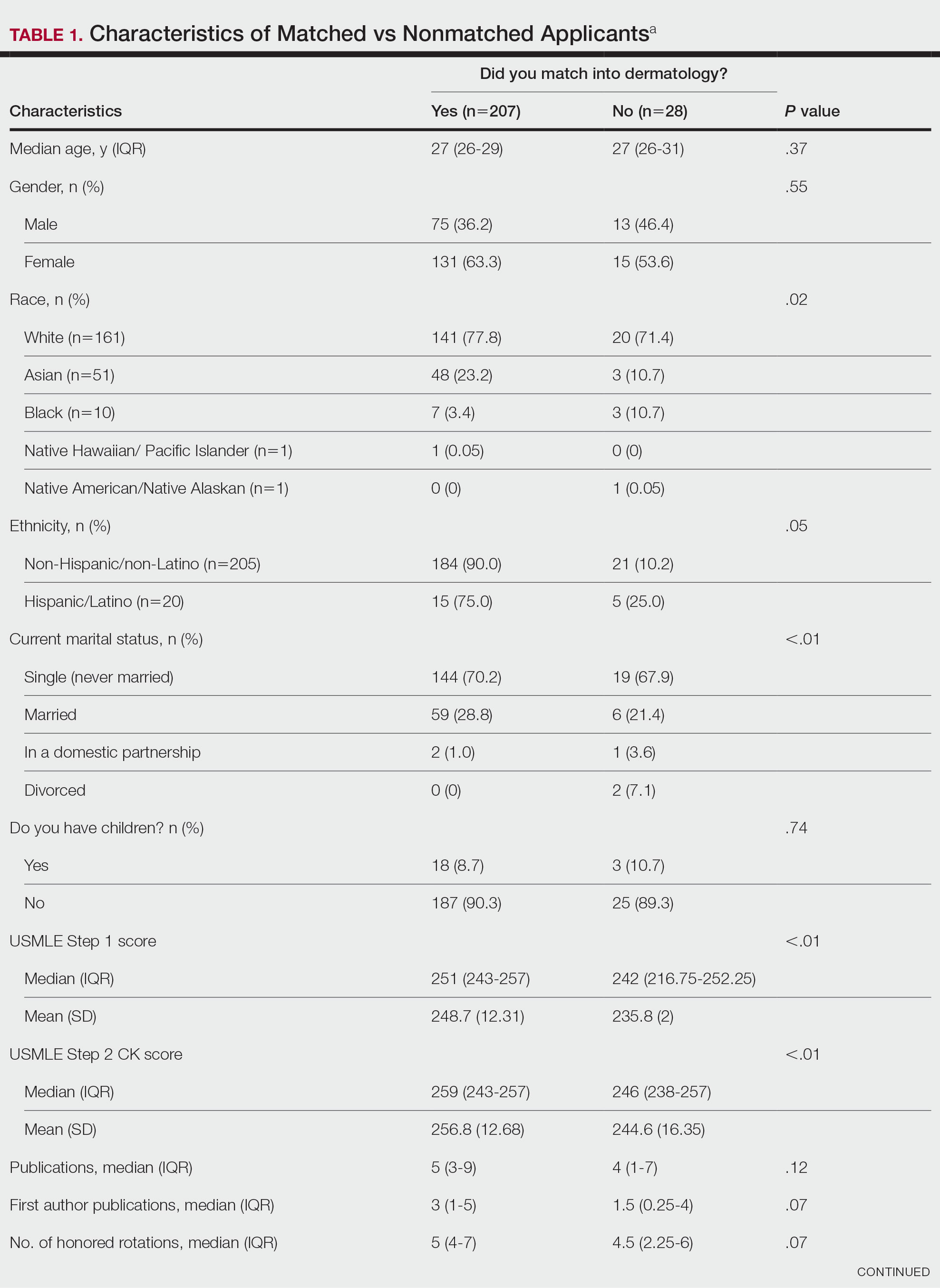

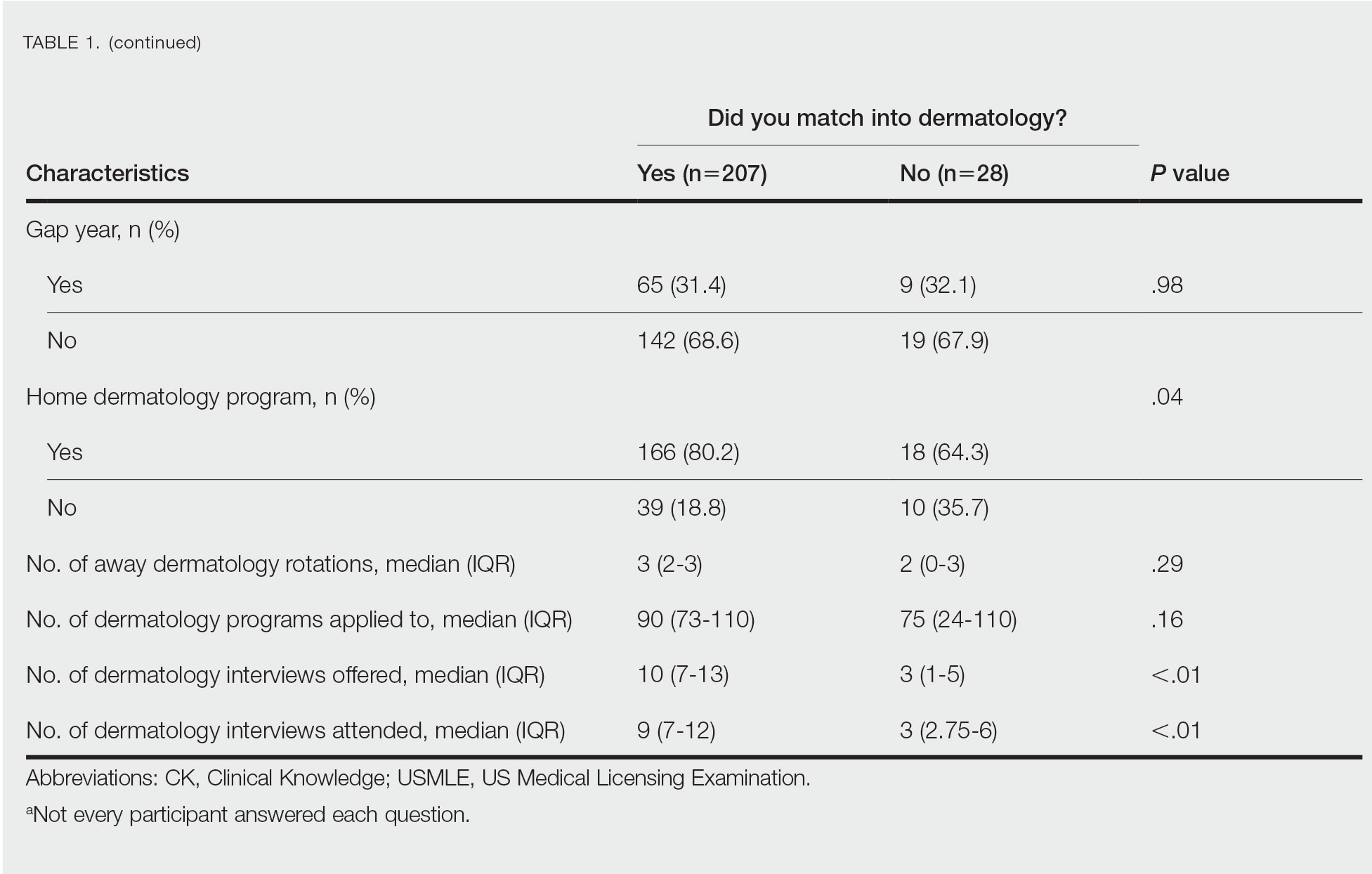

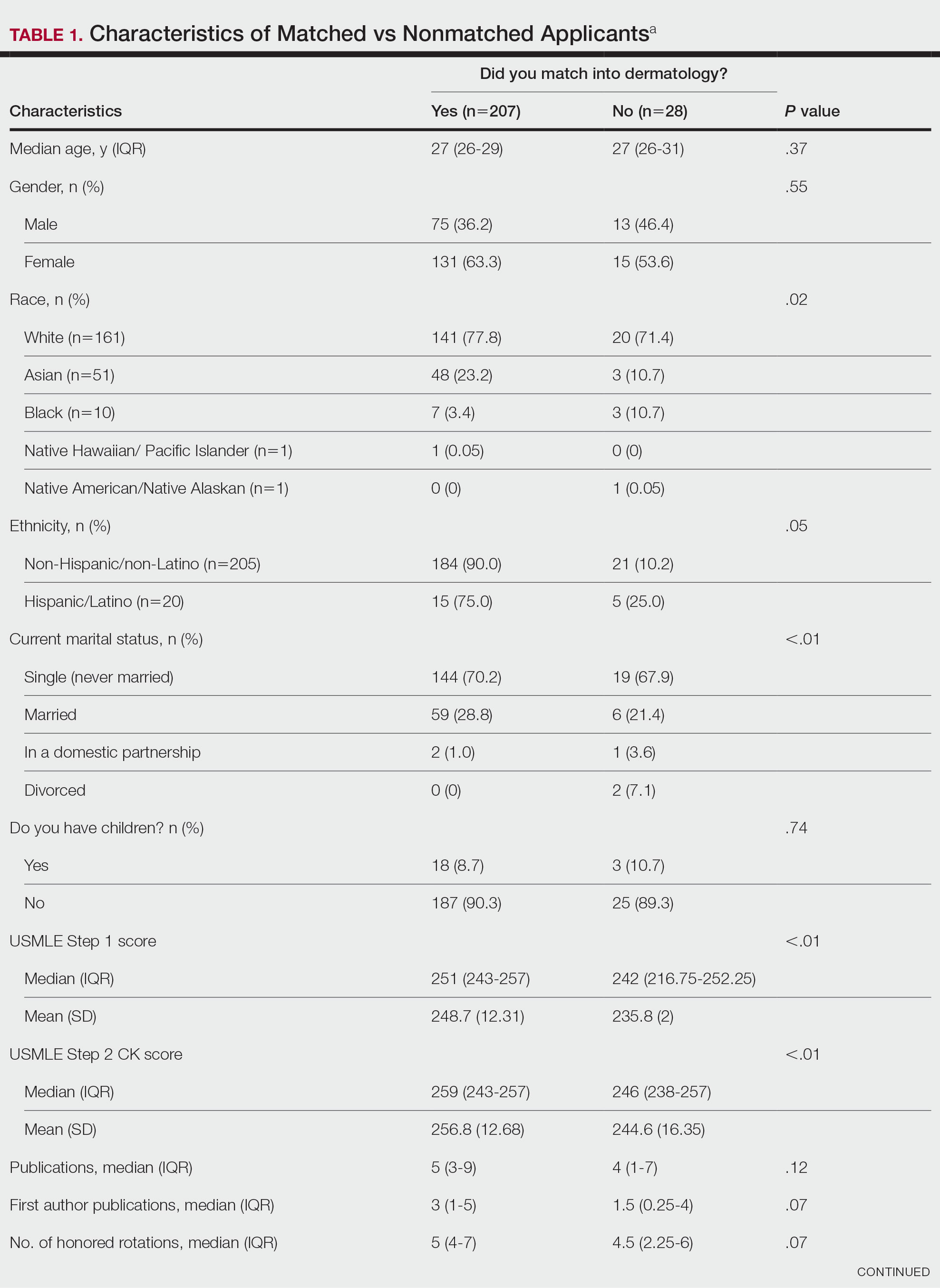

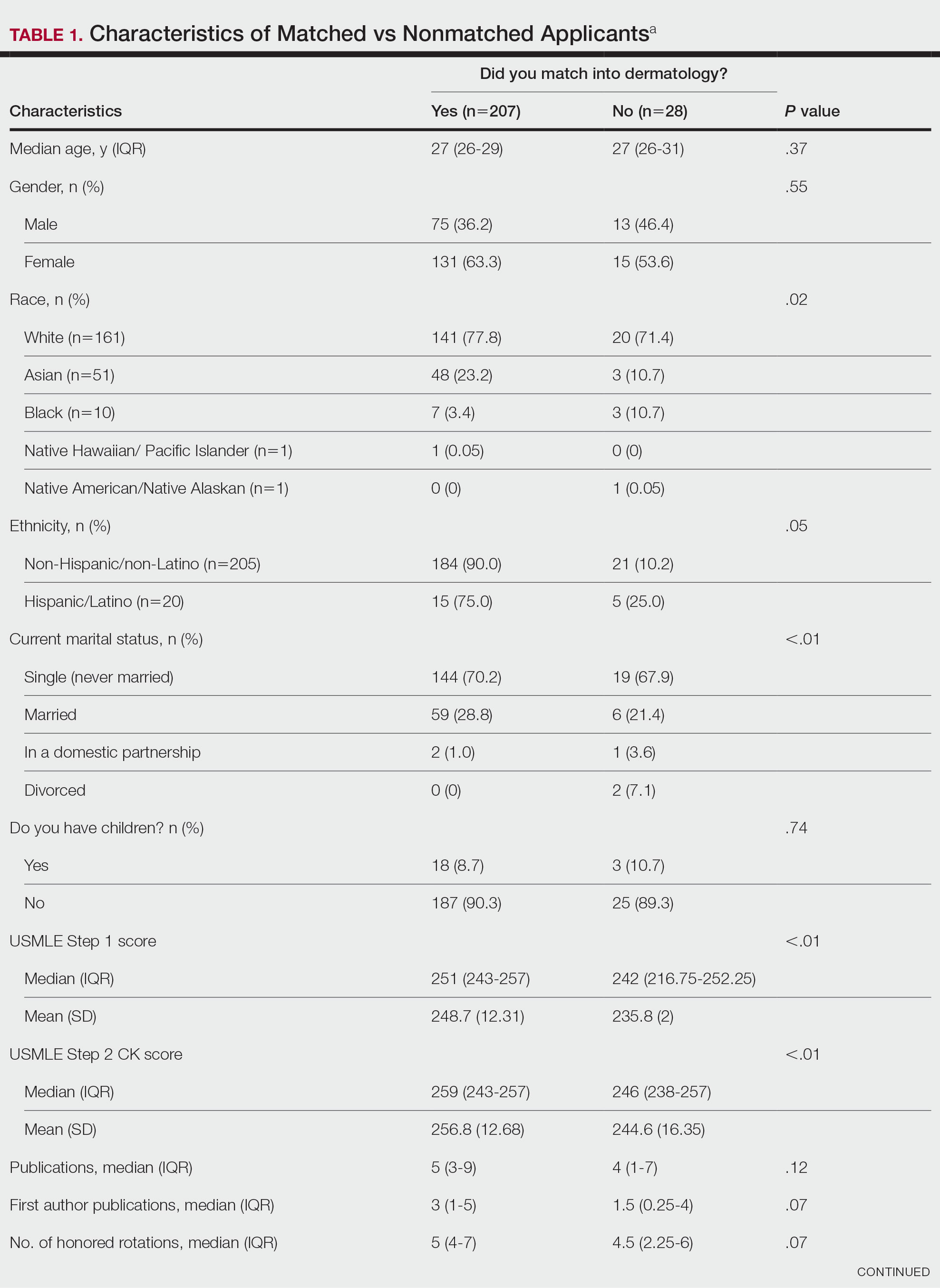

USMLE Scores—The median USMLE Step 1 score was 250, and scores ranged from 196 to 271. The median USMLE Step 2 CK score was 257, and scores ranged from 213 to 281. Higher USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores and more interviews were associated with higher match rates (Table 1). In addition, students with a dermatology program at their medical school were more likely to match than those without a home dermatology program.

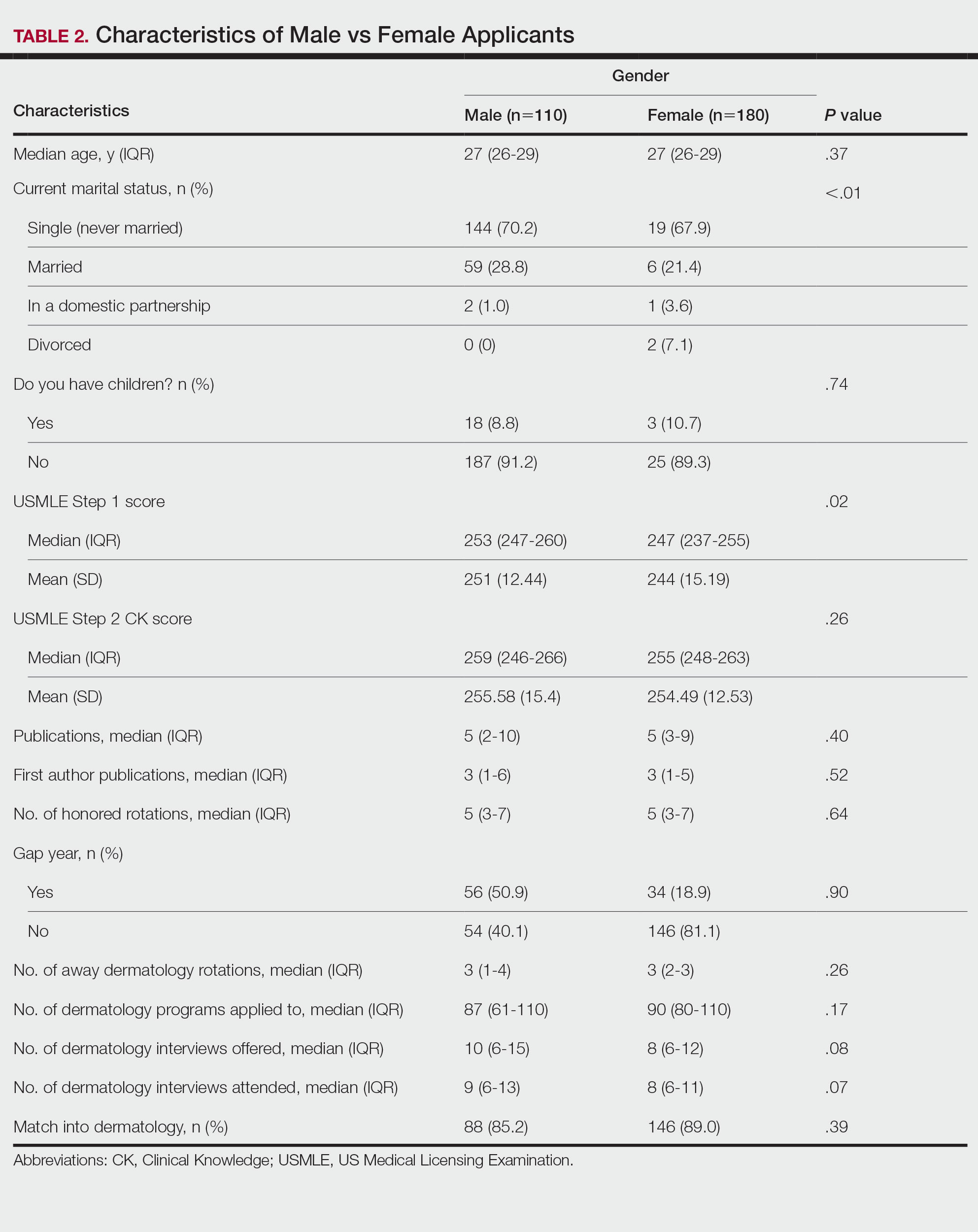

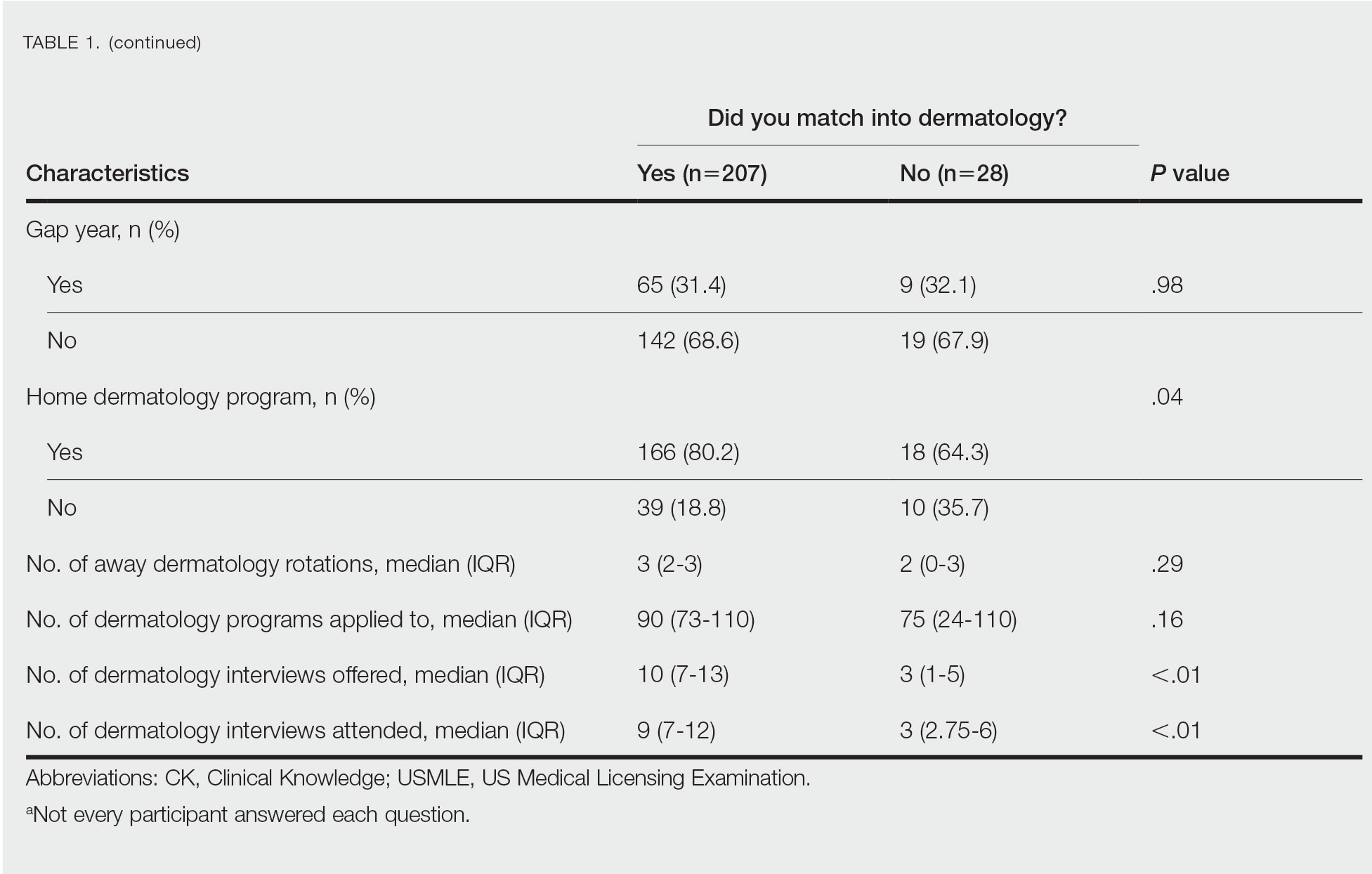

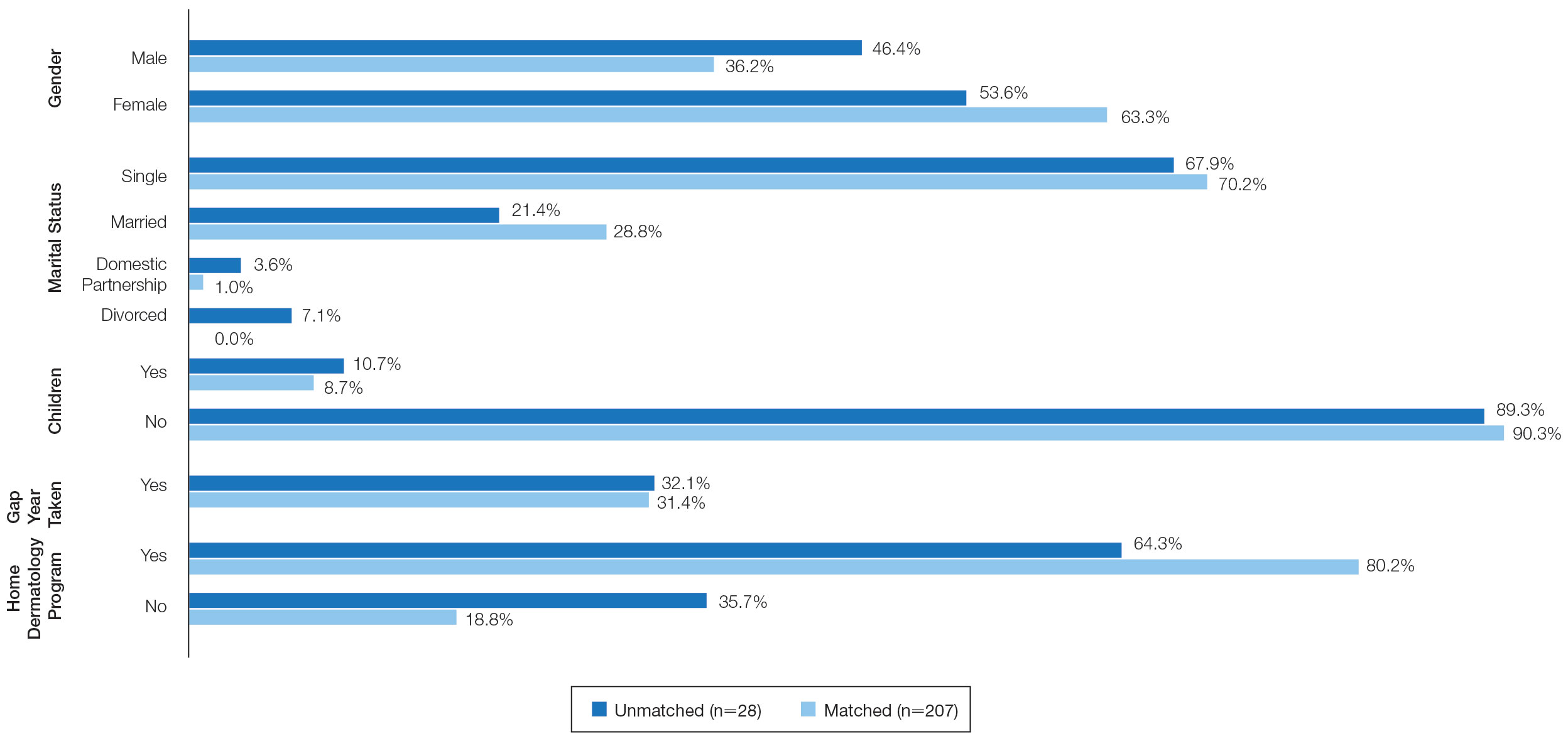

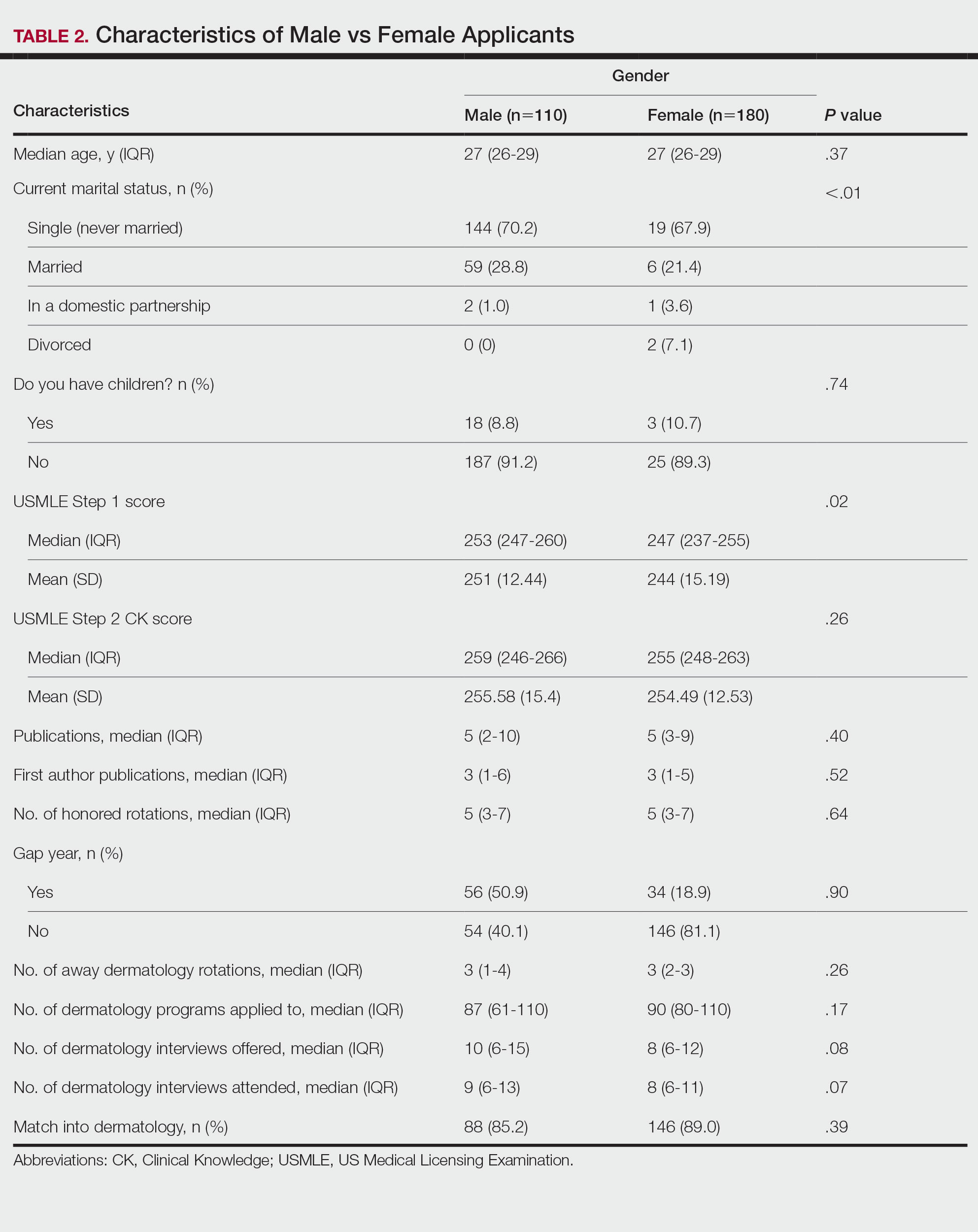

Gender Differences—There were 180 females and 110 males who completed the surveys. Males and females had similar match rates (85.2% vs 89.0%; P=.39)(Table 2).

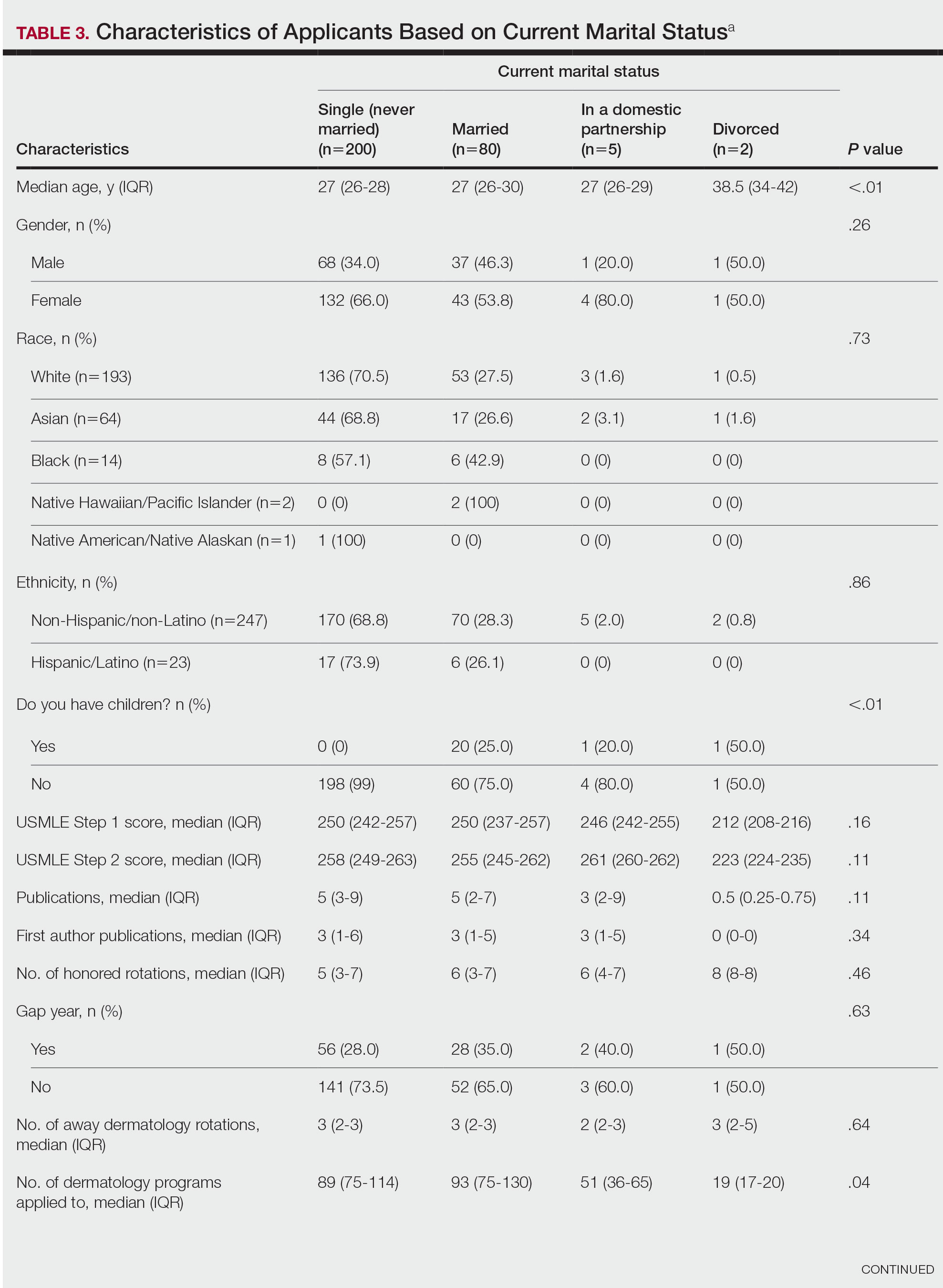

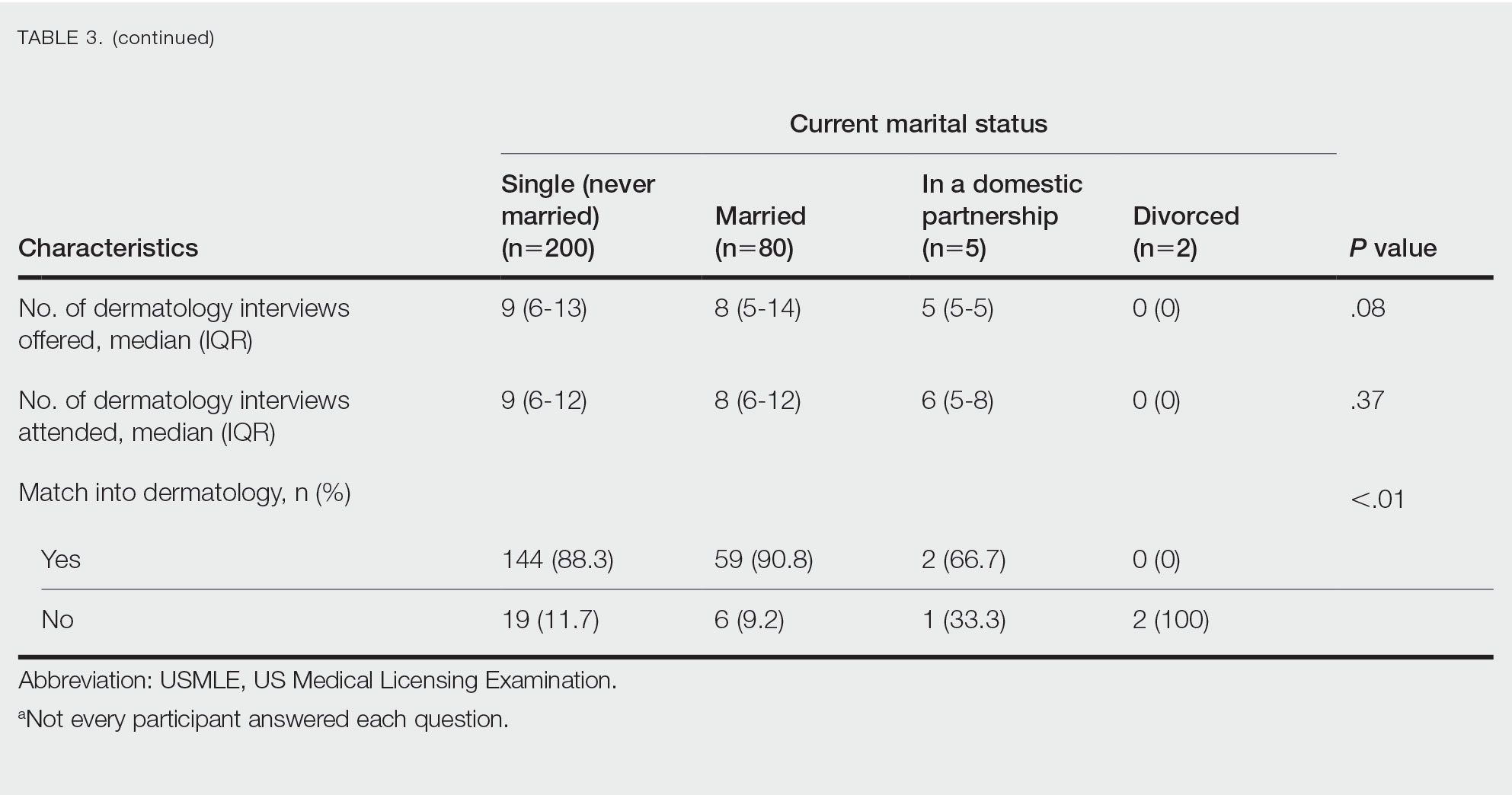

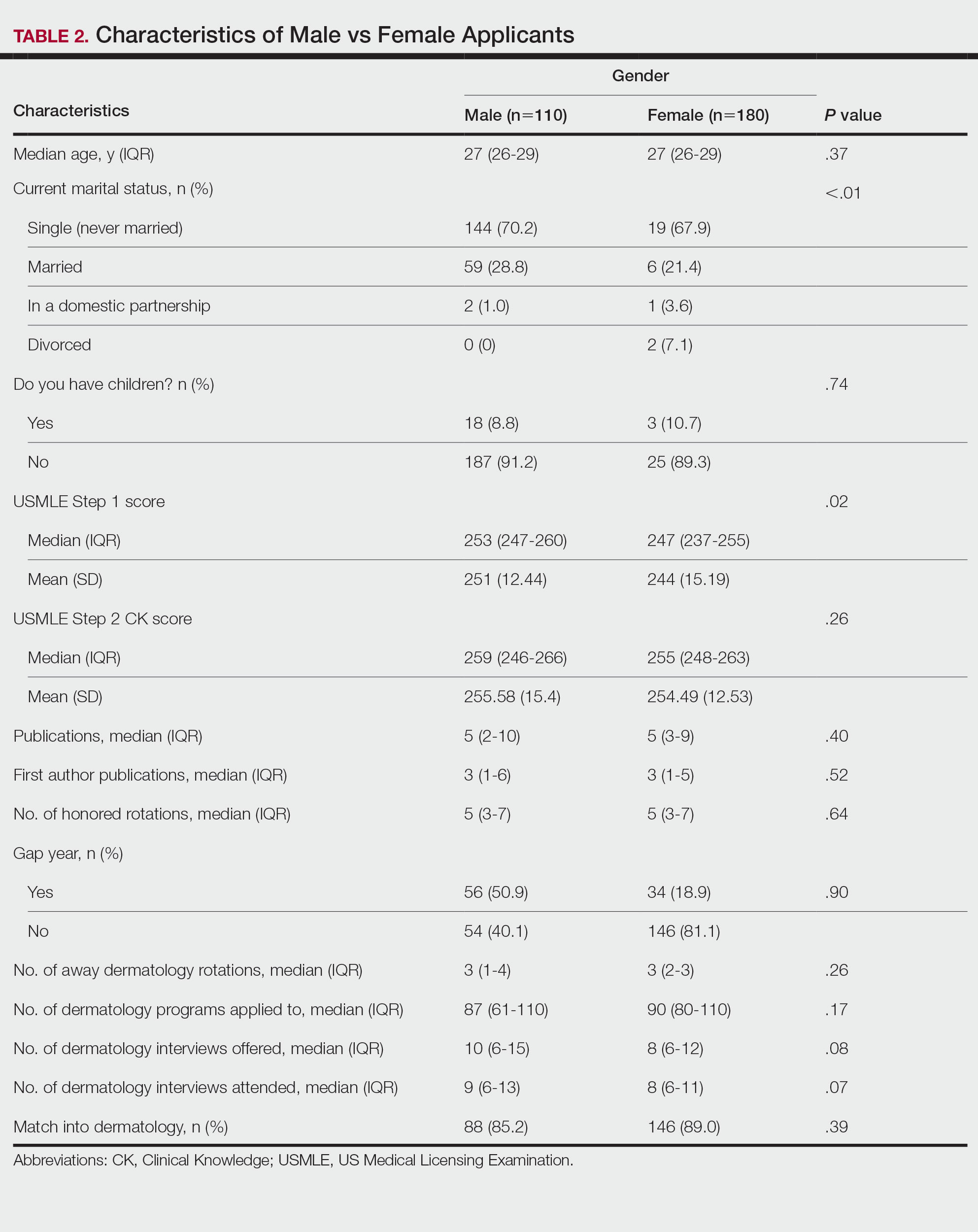

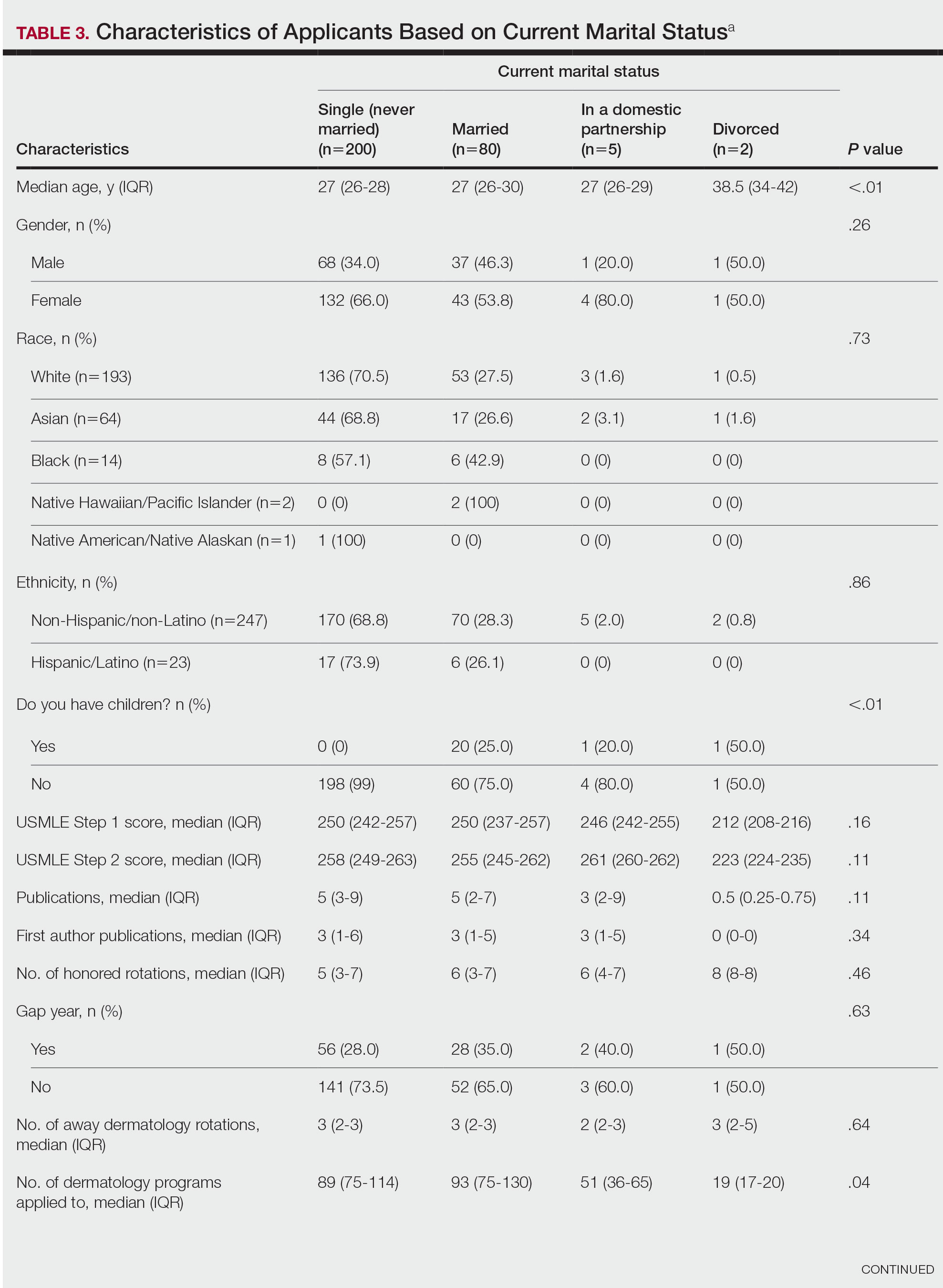

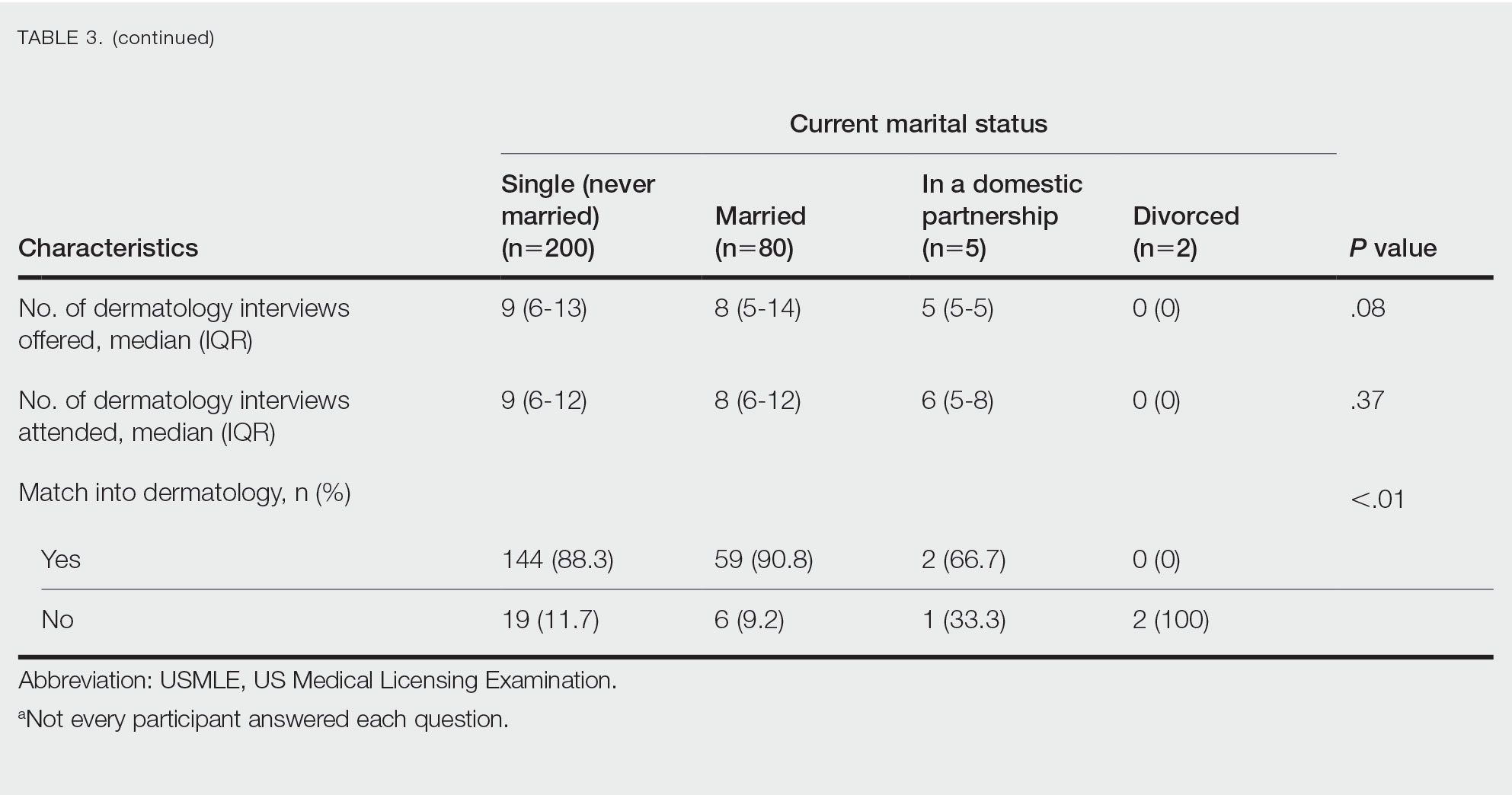

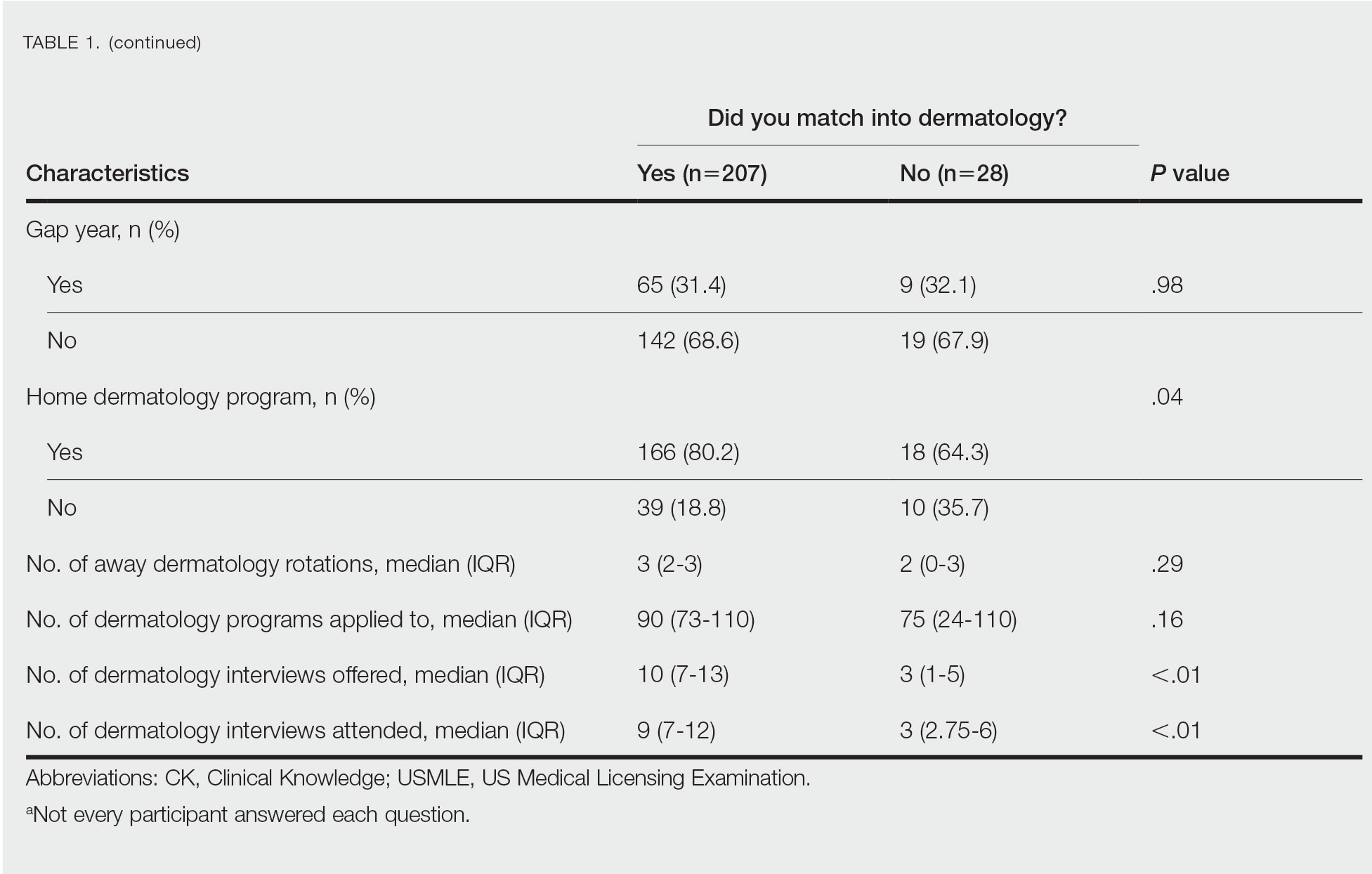

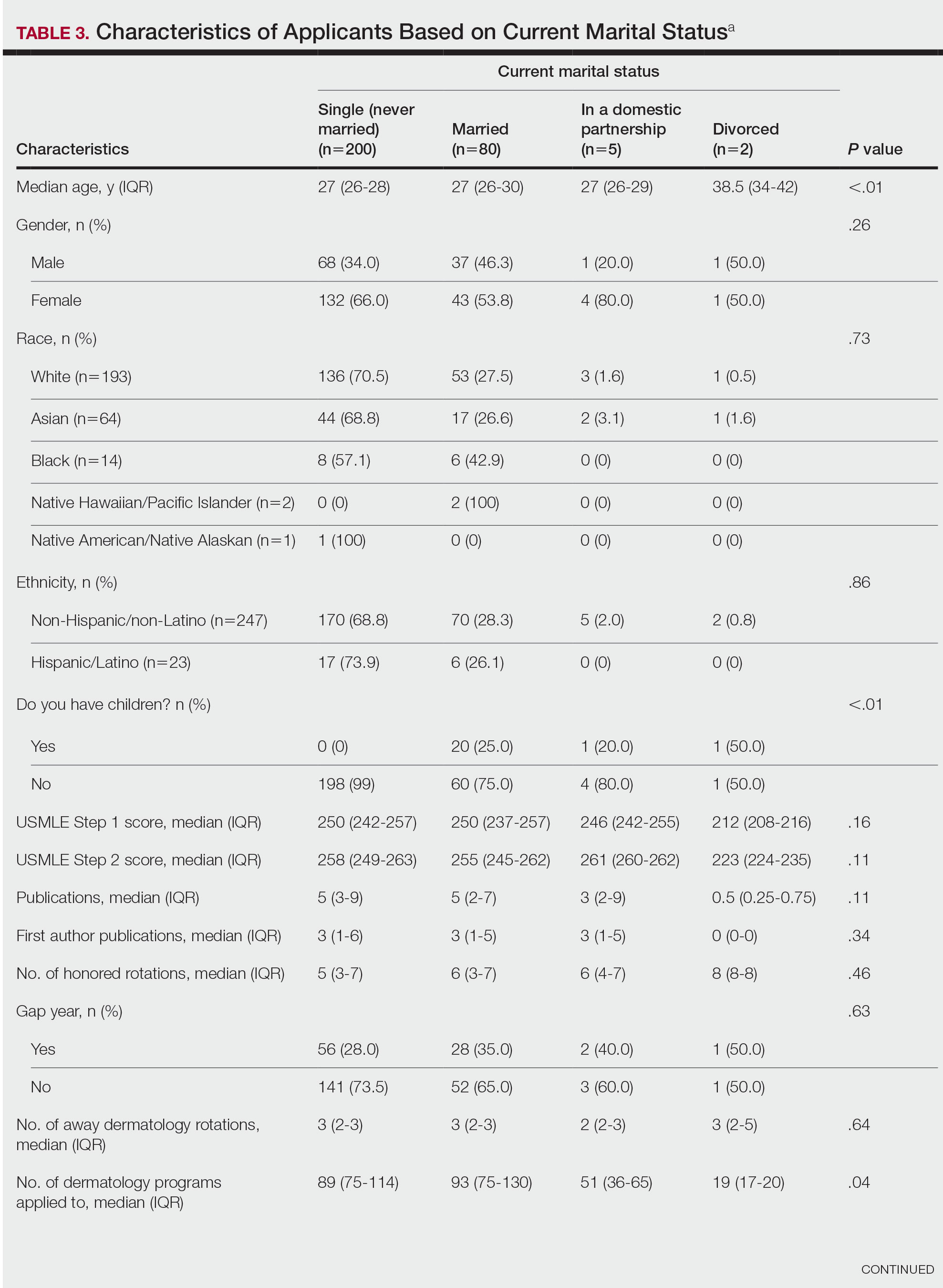

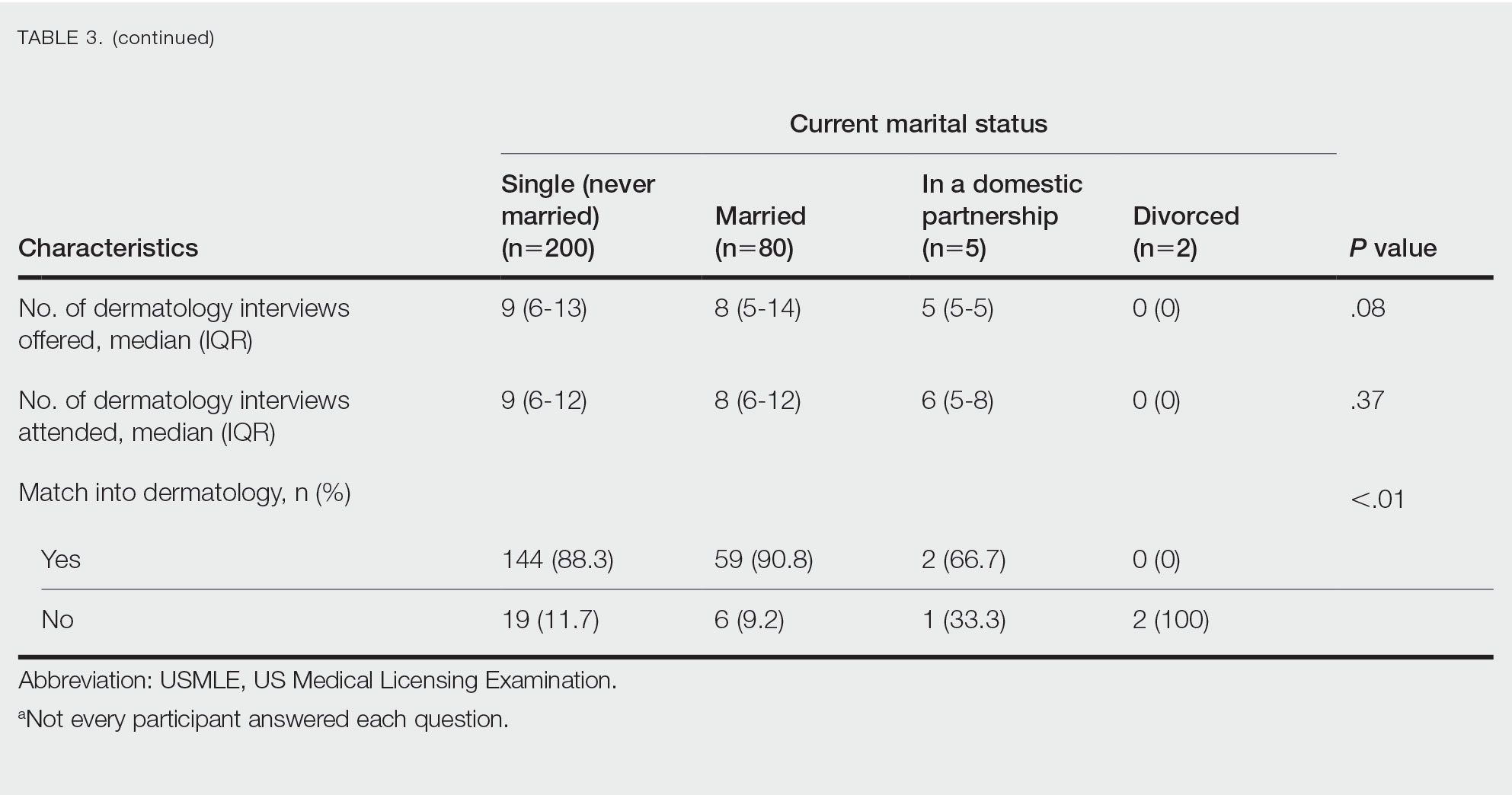

Family Life—In comparing marital status, applicants who were divorced had a higher median age (38.5 years) compared with applicants who were single, married, or in a domestic partnership (all 27 years; P<.01). Differences are outlined in Table 3.

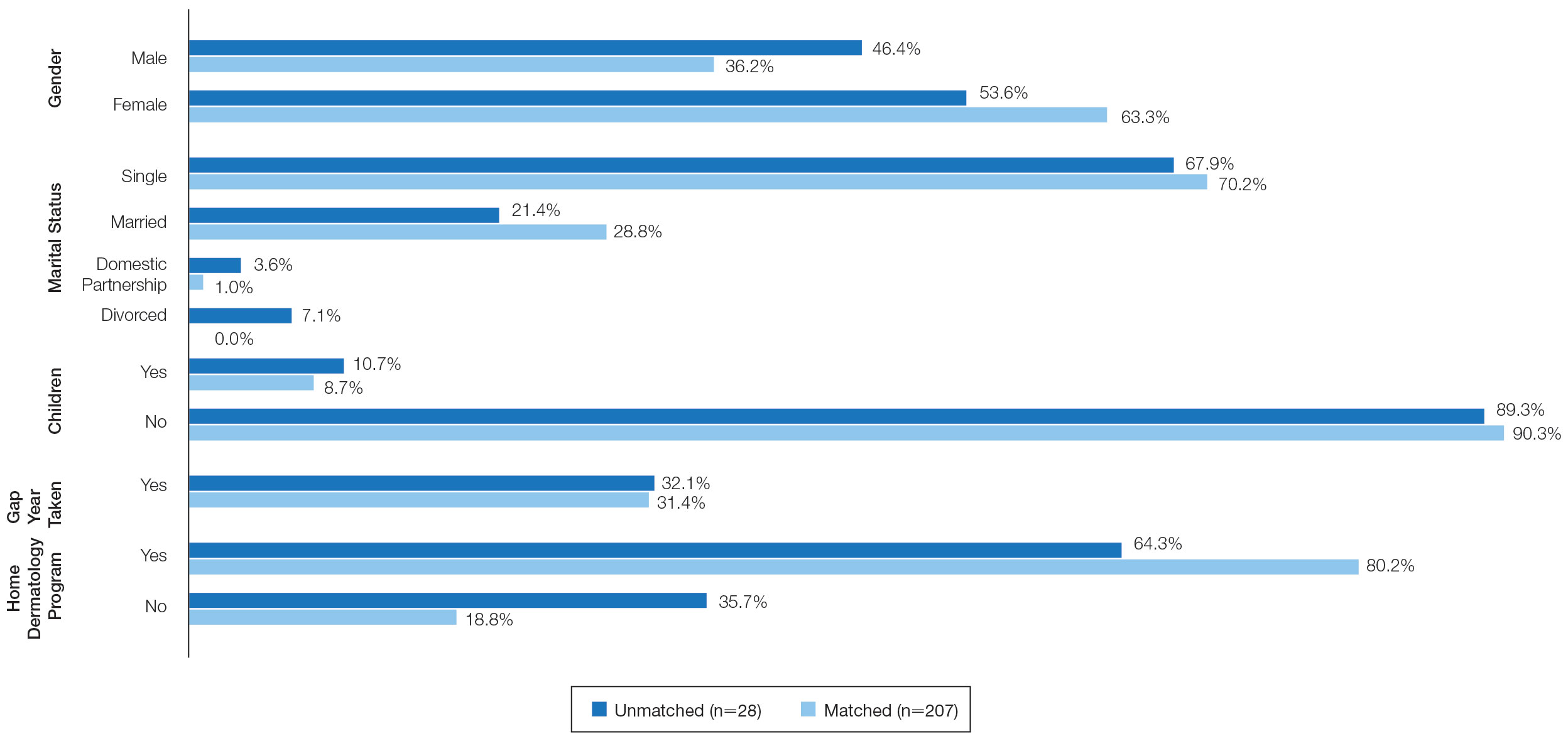

On average, applicants with children (n=27 [15 male, 12 female]; P=.13) were 3 years older than those without (30.5 vs 27; P<.01) and were more likely to be married (88.9% vs 21.5%; P<.01). Applicants with children had a mean USMLE Step 1 score of 241 compared to 251 for those without children (P=.02) and a mean USMLE Step 2 CK score of 246 compared to 258 for those without children (P<.01). Applicants with children had similar debt, number of publications, number of honored rotations, and match rates compared to applicants without children (Figure).

Couples Match—Seventeen individuals in our survey participated in the couples match (7.8%), and all 17 (100%) matched into dermatology. The mean age was 26.7 years, 12 applicants were female, 2 applicants were married, and 1 applicant had children. The mean number of interviews offered was 13.6, and the mean number of interviews attended was 11.3. This was higher than participants who were not couples matching (13.6 vs 9.8 [P=.02] and 11.3 vs 8.9 [P=.04], respectively). Applicants and their partners applied to programs and received interviews in a mean of 10 cities. Sixteen applicants reported that they contacted programs where their partner had interview offers. All participants’ rank lists included programs located in different cities than their partners’ ranked programs, and all but 1 participant ranked programs located in a different state than their partners’ ranked programs. Fifteen participants had options in their rank list for the applicant not to match, even if the partner would match. Similarly, 12 had the option for the applicant to match, even if the partner would not match. Fourteen (82.4%) matched at the same institution as their significant other. Three (17.6%) applicants matched to a program in a different state than the partner’s matched program. Two (11.8%) participants felt their relationship with their partner suffered because of the match, and 1 (5.9%) applicant was undetermined. One applicant described their relationship suffering from “unnecessary tension and anxiety” and noted “difficult conversations” about potentially matching into dermatology in a different location from their partner that could have been “devastating and not something [he or she] should have to choose.”

Comment

Factors for Matching in Dermatology—In our survey, we found the statistically significant factors of matching into dermatology included high USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores (P<.01), having a home dermatology program (P=.04), and attending a higher number of dermatology interviews (P<.01). These data are similar to NRMP results1; however, the higher likelihood of matching if the medical school has a home dermatology program has not been reported. This finding could be due to multiple factors such as students have less access to academic dermatologists for research projects, letters of recommendations, mentorship, and clinical rotations.

Gender and having children were factors that had no correlation with the match rate. There was a statistical difference of matching based on marital status (P<.01), but this is likely due to the low number of applicants in the divorced category. There were differences among demographics with USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores, which is a known factor in matching.1,2 Applicants with children had lower USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores compared to applicants without children. Females also had lower median USMLE Step 1 scores compared to males. This finding may serve as a reminder to programs when comparing USMLE Step examination scores that demographic factors may play a role. The race and ethnicity of applicants likely play a role. It has been reported that underrepresented minorities had lower match rates than White and Asian applicants in dermatology.6 There have been several published articles discussing the lack of diversity in dermatology, with a call to action.7-9

Factors for Couples Matching—The number of applicants participating in the couples match continues to increase yearly. The NMRP does publish data regarding “successful” couples matching but does not specify how many couples match together. There also is little published regarding advice for participation in the couples match. Although we had a limited number of couples that participated in the match, it is interesting to note they had similar strategies, including contacting programs at institutions that had offered interviews to their partners. This strategy may be effective, as dermatology programs offer interviews relatively late compared with other specialties.5 Additionally, this strategy may increase the number of interviews offered and received, as evidenced by the higher number of interviews offered compared with those who were not couples matching. Additionally, this survey highlights the sacrifice often needed by couples in the couples match as revealed by the inclusion of rank-list options in which the couples reside long distance or in which 1 partner does not match. This information may be helpful to applicants who are planning a strategy for the couples match in dermatology. Although this study does not encompass all dermatology applicants in the 2019-2020 cycle, we do believe it may be representative. The USMLE Step 1 scores in this study were similar to the published NRMP data.1,10 According to NRMP data from the 2019-2020 cycle, the mean USMLE Step 1 score was 248 for matched applicants and 239 for unmatched.1 The NRMP reported the mean USMLE Step 2 CK score for matched was 256 and 248 for unmatched, which also is similar to our data. The NRMP reported the mean number of programs ranked was 9.9 for matched and 4.5 for unmatched applicants.1 Again, our data were similar for number of dermatology interviews attended.

Limitations—There are limitations to this study. The main limitation is that the survey is from a single institution and had a limited number of respondents. Given the nature of the study, the accuracy of the data is dependent on the applicants’ honesty in self-reporting academic performance and other variables. There also may be a selection bias given the low response rate. The subanalyses—children and couples matching—were underpowered with the limited number of participants. Further studies that include multiple residency programs and multiple years could be helpful to provide more power and less risk of bias. We did not gather information such as the Medical Student Performance Evaluation letter, letters of recommendation, or personal statements, which do play an important role in the assessment of an applicant. However, because the applicants completed these surveys, and given these are largely blinded to applicants, we did not feel the applicants could accurately respond to those aspects of the application.

Conclusion

Our survey finds that factors associated with matching included a higher USMLE Step 1 score, having a home dermatology program, and a higher number of interviews offered and attended. Some demographics had varying USMLE Step 1 scores but similar match rates.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2020 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; May 2020. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/MM_Results_and-Data_2020-1.pdf

- Gauer JL, Jackson JB. The association of USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores with residency match specialty and location. Med Educ Online. 2017;22:1358579.

- Wang JV, Keller M. Pressure to publish for residency applicants in dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt56x1t7ww.

- Wang RF, Zhang M, Kaffenberger JA. Does the dermatology standardized letter of recommendation alter applicants’ chances of matching into residency. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:e139-e140.

- National Resident Matching Program, Data Release and Research Committee: results of the 2018 NRMP Program Director Survey. Accessed December 19, 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/NRMP-2018-Program-Director-Survey-for-WWW.pdf

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role of race and ethnicity in the dermatology applicant match process. J Natl Med Assoc. 2022;113:666-670.

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants-turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Van Voorhees AS, Enos CW. Diversity in dermatology residency programs. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S46-S49.

- National Resident Matching Program. Charting outcomes in the match: U.S. allopathic seniors. Characteristics of U.S. allopathic seniors who matched to their preferred specialty in the 2018 main residency match. 2nd ed. Accessed December 19, 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2018_Seniors-1.pdf

Dermatology residency continues to be one of the most competitive specialties, with a match rate of 84.7% for US allopathic seniors in the 2019-2020 academic year.1 In the 2019-2020 cycle, dermatology applicants were tied with plastic surgery for the highest median US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score compared with other specialties, which suggests that the top medical students are applying, yet only approximately 5 of 6 students are matching.

Factors that have been cited with successful dermatology matching include USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 Clinical Knowledge (CK) scores,2 research accomplishments,3 letters of recommendation,4 medical school performance, personal statement, grades in required clerkships, and volunteer/extracurricular experiences, among others.5

The National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) publishes data each year regarding different academic factors—USMLE scores; number of abstracts, presentations, and papers; work, volunteer, and research experiences—and compares the mean between matched and nonmatched applicants.1 However, the USMLE does not report any demographic information of the applicants and the implication it has for matching. Additionally, the number of couples participating in the couples match continues to increase each year. In the 2019-2020 cycle, 1224 couples participated in the couples match.1 However, NRMP reports only limited data regarding the couples match, and it is not specialty specific.

We aimed to determine the characteristics of matched vs nonmatched dermatology applicants. Secondarily, we aimed to determine any differences among demographics regarding matching rates, academic performance, and research publications. We also aimed to characterize the strategy and outcomes of applicants that couples matched.

Materials and Methods

The Mayo Clinic institutional review board deemed this study exempt. All applicants who applied to Mayo Clinic dermatology residency in Scottsdale, Arizona, during the 2018-2019 cycle were emailed an initial survey (N=475) before Match Day that obtained demographic information, geographic information, gap-year information, USMLE Step 1 score, publications, medical school grades, number of away rotations, and number of interviews. A follow-up survey gathering match data and couples matching data was sent to the applicants who completed the first survey on Match Day. The survey was repeated for the 2019-2020 cycle. In the second survey, Step 2 CK data were obtained. The survey was sent to 629 applicants who applied to Mayo Clinic dermatology residencies in Arizona, Minnesota, and Florida to include a broader group of applicants. For publications, applicants were asked to count only published or accepted manuscripts, not abstracts, posters, conference presentations, or submitted manuscripts. Applicants who did not respond to the second survey (match data) were not included in that part of the analysis. One survey was excluded because of implausible answers (eg, scores outside of range for USMLE Step scores).

Statistical Analysis—For statistical analyses, the applicants from both applications cycles were combined. Descriptive statistics were reported in the form of mean, median, or counts (percentages), as applicable. Means were compared using 2-sided t tests. Group comparisons were examined using χ2 tests for categorical variables. Statistical analyses were performed using the BlueSky Statistics version 6.30. P<.05 was considered significant.

Results

In 2019, a total of 149 applicants completed the initial survey (31.4% response rate), and 112 completed the follow-up survey (75.2% response rate). In 2020, a total of 142 applicants completed the initial survey (22.6% response rate), and 124 completed the follow-up survey (87.3% response rate). Combining the 2 years, after removing 1 survey with implausible answers, there were 290 respondents from the initial survey and 235 from the follow-up survey. The median (SD) age for the total applicants over both years was 27 (3.0) years, and 180 applicants were female (61.9%).

USMLE Scores—The median USMLE Step 1 score was 250, and scores ranged from 196 to 271. The median USMLE Step 2 CK score was 257, and scores ranged from 213 to 281. Higher USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores and more interviews were associated with higher match rates (Table 1). In addition, students with a dermatology program at their medical school were more likely to match than those without a home dermatology program.

Gender Differences—There were 180 females and 110 males who completed the surveys. Males and females had similar match rates (85.2% vs 89.0%; P=.39)(Table 2).

Family Life—In comparing marital status, applicants who were divorced had a higher median age (38.5 years) compared with applicants who were single, married, or in a domestic partnership (all 27 years; P<.01). Differences are outlined in Table 3.

On average, applicants with children (n=27 [15 male, 12 female]; P=.13) were 3 years older than those without (30.5 vs 27; P<.01) and were more likely to be married (88.9% vs 21.5%; P<.01). Applicants with children had a mean USMLE Step 1 score of 241 compared to 251 for those without children (P=.02) and a mean USMLE Step 2 CK score of 246 compared to 258 for those without children (P<.01). Applicants with children had similar debt, number of publications, number of honored rotations, and match rates compared to applicants without children (Figure).

Couples Match—Seventeen individuals in our survey participated in the couples match (7.8%), and all 17 (100%) matched into dermatology. The mean age was 26.7 years, 12 applicants were female, 2 applicants were married, and 1 applicant had children. The mean number of interviews offered was 13.6, and the mean number of interviews attended was 11.3. This was higher than participants who were not couples matching (13.6 vs 9.8 [P=.02] and 11.3 vs 8.9 [P=.04], respectively). Applicants and their partners applied to programs and received interviews in a mean of 10 cities. Sixteen applicants reported that they contacted programs where their partner had interview offers. All participants’ rank lists included programs located in different cities than their partners’ ranked programs, and all but 1 participant ranked programs located in a different state than their partners’ ranked programs. Fifteen participants had options in their rank list for the applicant not to match, even if the partner would match. Similarly, 12 had the option for the applicant to match, even if the partner would not match. Fourteen (82.4%) matched at the same institution as their significant other. Three (17.6%) applicants matched to a program in a different state than the partner’s matched program. Two (11.8%) participants felt their relationship with their partner suffered because of the match, and 1 (5.9%) applicant was undetermined. One applicant described their relationship suffering from “unnecessary tension and anxiety” and noted “difficult conversations” about potentially matching into dermatology in a different location from their partner that could have been “devastating and not something [he or she] should have to choose.”

Comment

Factors for Matching in Dermatology—In our survey, we found the statistically significant factors of matching into dermatology included high USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores (P<.01), having a home dermatology program (P=.04), and attending a higher number of dermatology interviews (P<.01). These data are similar to NRMP results1; however, the higher likelihood of matching if the medical school has a home dermatology program has not been reported. This finding could be due to multiple factors such as students have less access to academic dermatologists for research projects, letters of recommendations, mentorship, and clinical rotations.

Gender and having children were factors that had no correlation with the match rate. There was a statistical difference of matching based on marital status (P<.01), but this is likely due to the low number of applicants in the divorced category. There were differences among demographics with USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores, which is a known factor in matching.1,2 Applicants with children had lower USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores compared to applicants without children. Females also had lower median USMLE Step 1 scores compared to males. This finding may serve as a reminder to programs when comparing USMLE Step examination scores that demographic factors may play a role. The race and ethnicity of applicants likely play a role. It has been reported that underrepresented minorities had lower match rates than White and Asian applicants in dermatology.6 There have been several published articles discussing the lack of diversity in dermatology, with a call to action.7-9

Factors for Couples Matching—The number of applicants participating in the couples match continues to increase yearly. The NMRP does publish data regarding “successful” couples matching but does not specify how many couples match together. There also is little published regarding advice for participation in the couples match. Although we had a limited number of couples that participated in the match, it is interesting to note they had similar strategies, including contacting programs at institutions that had offered interviews to their partners. This strategy may be effective, as dermatology programs offer interviews relatively late compared with other specialties.5 Additionally, this strategy may increase the number of interviews offered and received, as evidenced by the higher number of interviews offered compared with those who were not couples matching. Additionally, this survey highlights the sacrifice often needed by couples in the couples match as revealed by the inclusion of rank-list options in which the couples reside long distance or in which 1 partner does not match. This information may be helpful to applicants who are planning a strategy for the couples match in dermatology. Although this study does not encompass all dermatology applicants in the 2019-2020 cycle, we do believe it may be representative. The USMLE Step 1 scores in this study were similar to the published NRMP data.1,10 According to NRMP data from the 2019-2020 cycle, the mean USMLE Step 1 score was 248 for matched applicants and 239 for unmatched.1 The NRMP reported the mean USMLE Step 2 CK score for matched was 256 and 248 for unmatched, which also is similar to our data. The NRMP reported the mean number of programs ranked was 9.9 for matched and 4.5 for unmatched applicants.1 Again, our data were similar for number of dermatology interviews attended.

Limitations—There are limitations to this study. The main limitation is that the survey is from a single institution and had a limited number of respondents. Given the nature of the study, the accuracy of the data is dependent on the applicants’ honesty in self-reporting academic performance and other variables. There also may be a selection bias given the low response rate. The subanalyses—children and couples matching—were underpowered with the limited number of participants. Further studies that include multiple residency programs and multiple years could be helpful to provide more power and less risk of bias. We did not gather information such as the Medical Student Performance Evaluation letter, letters of recommendation, or personal statements, which do play an important role in the assessment of an applicant. However, because the applicants completed these surveys, and given these are largely blinded to applicants, we did not feel the applicants could accurately respond to those aspects of the application.

Conclusion

Our survey finds that factors associated with matching included a higher USMLE Step 1 score, having a home dermatology program, and a higher number of interviews offered and attended. Some demographics had varying USMLE Step 1 scores but similar match rates.

Dermatology residency continues to be one of the most competitive specialties, with a match rate of 84.7% for US allopathic seniors in the 2019-2020 academic year.1 In the 2019-2020 cycle, dermatology applicants were tied with plastic surgery for the highest median US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score compared with other specialties, which suggests that the top medical students are applying, yet only approximately 5 of 6 students are matching.

Factors that have been cited with successful dermatology matching include USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 Clinical Knowledge (CK) scores,2 research accomplishments,3 letters of recommendation,4 medical school performance, personal statement, grades in required clerkships, and volunteer/extracurricular experiences, among others.5

The National Resident Matching Program (NRMP) publishes data each year regarding different academic factors—USMLE scores; number of abstracts, presentations, and papers; work, volunteer, and research experiences—and compares the mean between matched and nonmatched applicants.1 However, the USMLE does not report any demographic information of the applicants and the implication it has for matching. Additionally, the number of couples participating in the couples match continues to increase each year. In the 2019-2020 cycle, 1224 couples participated in the couples match.1 However, NRMP reports only limited data regarding the couples match, and it is not specialty specific.

We aimed to determine the characteristics of matched vs nonmatched dermatology applicants. Secondarily, we aimed to determine any differences among demographics regarding matching rates, academic performance, and research publications. We also aimed to characterize the strategy and outcomes of applicants that couples matched.

Materials and Methods

The Mayo Clinic institutional review board deemed this study exempt. All applicants who applied to Mayo Clinic dermatology residency in Scottsdale, Arizona, during the 2018-2019 cycle were emailed an initial survey (N=475) before Match Day that obtained demographic information, geographic information, gap-year information, USMLE Step 1 score, publications, medical school grades, number of away rotations, and number of interviews. A follow-up survey gathering match data and couples matching data was sent to the applicants who completed the first survey on Match Day. The survey was repeated for the 2019-2020 cycle. In the second survey, Step 2 CK data were obtained. The survey was sent to 629 applicants who applied to Mayo Clinic dermatology residencies in Arizona, Minnesota, and Florida to include a broader group of applicants. For publications, applicants were asked to count only published or accepted manuscripts, not abstracts, posters, conference presentations, or submitted manuscripts. Applicants who did not respond to the second survey (match data) were not included in that part of the analysis. One survey was excluded because of implausible answers (eg, scores outside of range for USMLE Step scores).

Statistical Analysis—For statistical analyses, the applicants from both applications cycles were combined. Descriptive statistics were reported in the form of mean, median, or counts (percentages), as applicable. Means were compared using 2-sided t tests. Group comparisons were examined using χ2 tests for categorical variables. Statistical analyses were performed using the BlueSky Statistics version 6.30. P<.05 was considered significant.

Results

In 2019, a total of 149 applicants completed the initial survey (31.4% response rate), and 112 completed the follow-up survey (75.2% response rate). In 2020, a total of 142 applicants completed the initial survey (22.6% response rate), and 124 completed the follow-up survey (87.3% response rate). Combining the 2 years, after removing 1 survey with implausible answers, there were 290 respondents from the initial survey and 235 from the follow-up survey. The median (SD) age for the total applicants over both years was 27 (3.0) years, and 180 applicants were female (61.9%).

USMLE Scores—The median USMLE Step 1 score was 250, and scores ranged from 196 to 271. The median USMLE Step 2 CK score was 257, and scores ranged from 213 to 281. Higher USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores and more interviews were associated with higher match rates (Table 1). In addition, students with a dermatology program at their medical school were more likely to match than those without a home dermatology program.

Gender Differences—There were 180 females and 110 males who completed the surveys. Males and females had similar match rates (85.2% vs 89.0%; P=.39)(Table 2).

Family Life—In comparing marital status, applicants who were divorced had a higher median age (38.5 years) compared with applicants who were single, married, or in a domestic partnership (all 27 years; P<.01). Differences are outlined in Table 3.

On average, applicants with children (n=27 [15 male, 12 female]; P=.13) were 3 years older than those without (30.5 vs 27; P<.01) and were more likely to be married (88.9% vs 21.5%; P<.01). Applicants with children had a mean USMLE Step 1 score of 241 compared to 251 for those without children (P=.02) and a mean USMLE Step 2 CK score of 246 compared to 258 for those without children (P<.01). Applicants with children had similar debt, number of publications, number of honored rotations, and match rates compared to applicants without children (Figure).

Couples Match—Seventeen individuals in our survey participated in the couples match (7.8%), and all 17 (100%) matched into dermatology. The mean age was 26.7 years, 12 applicants were female, 2 applicants were married, and 1 applicant had children. The mean number of interviews offered was 13.6, and the mean number of interviews attended was 11.3. This was higher than participants who were not couples matching (13.6 vs 9.8 [P=.02] and 11.3 vs 8.9 [P=.04], respectively). Applicants and their partners applied to programs and received interviews in a mean of 10 cities. Sixteen applicants reported that they contacted programs where their partner had interview offers. All participants’ rank lists included programs located in different cities than their partners’ ranked programs, and all but 1 participant ranked programs located in a different state than their partners’ ranked programs. Fifteen participants had options in their rank list for the applicant not to match, even if the partner would match. Similarly, 12 had the option for the applicant to match, even if the partner would not match. Fourteen (82.4%) matched at the same institution as their significant other. Three (17.6%) applicants matched to a program in a different state than the partner’s matched program. Two (11.8%) participants felt their relationship with their partner suffered because of the match, and 1 (5.9%) applicant was undetermined. One applicant described their relationship suffering from “unnecessary tension and anxiety” and noted “difficult conversations” about potentially matching into dermatology in a different location from their partner that could have been “devastating and not something [he or she] should have to choose.”

Comment

Factors for Matching in Dermatology—In our survey, we found the statistically significant factors of matching into dermatology included high USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores (P<.01), having a home dermatology program (P=.04), and attending a higher number of dermatology interviews (P<.01). These data are similar to NRMP results1; however, the higher likelihood of matching if the medical school has a home dermatology program has not been reported. This finding could be due to multiple factors such as students have less access to academic dermatologists for research projects, letters of recommendations, mentorship, and clinical rotations.

Gender and having children were factors that had no correlation with the match rate. There was a statistical difference of matching based on marital status (P<.01), but this is likely due to the low number of applicants in the divorced category. There were differences among demographics with USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores, which is a known factor in matching.1,2 Applicants with children had lower USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores compared to applicants without children. Females also had lower median USMLE Step 1 scores compared to males. This finding may serve as a reminder to programs when comparing USMLE Step examination scores that demographic factors may play a role. The race and ethnicity of applicants likely play a role. It has been reported that underrepresented minorities had lower match rates than White and Asian applicants in dermatology.6 There have been several published articles discussing the lack of diversity in dermatology, with a call to action.7-9

Factors for Couples Matching—The number of applicants participating in the couples match continues to increase yearly. The NMRP does publish data regarding “successful” couples matching but does not specify how many couples match together. There also is little published regarding advice for participation in the couples match. Although we had a limited number of couples that participated in the match, it is interesting to note they had similar strategies, including contacting programs at institutions that had offered interviews to their partners. This strategy may be effective, as dermatology programs offer interviews relatively late compared with other specialties.5 Additionally, this strategy may increase the number of interviews offered and received, as evidenced by the higher number of interviews offered compared with those who were not couples matching. Additionally, this survey highlights the sacrifice often needed by couples in the couples match as revealed by the inclusion of rank-list options in which the couples reside long distance or in which 1 partner does not match. This information may be helpful to applicants who are planning a strategy for the couples match in dermatology. Although this study does not encompass all dermatology applicants in the 2019-2020 cycle, we do believe it may be representative. The USMLE Step 1 scores in this study were similar to the published NRMP data.1,10 According to NRMP data from the 2019-2020 cycle, the mean USMLE Step 1 score was 248 for matched applicants and 239 for unmatched.1 The NRMP reported the mean USMLE Step 2 CK score for matched was 256 and 248 for unmatched, which also is similar to our data. The NRMP reported the mean number of programs ranked was 9.9 for matched and 4.5 for unmatched applicants.1 Again, our data were similar for number of dermatology interviews attended.

Limitations—There are limitations to this study. The main limitation is that the survey is from a single institution and had a limited number of respondents. Given the nature of the study, the accuracy of the data is dependent on the applicants’ honesty in self-reporting academic performance and other variables. There also may be a selection bias given the low response rate. The subanalyses—children and couples matching—were underpowered with the limited number of participants. Further studies that include multiple residency programs and multiple years could be helpful to provide more power and less risk of bias. We did not gather information such as the Medical Student Performance Evaluation letter, letters of recommendation, or personal statements, which do play an important role in the assessment of an applicant. However, because the applicants completed these surveys, and given these are largely blinded to applicants, we did not feel the applicants could accurately respond to those aspects of the application.

Conclusion

Our survey finds that factors associated with matching included a higher USMLE Step 1 score, having a home dermatology program, and a higher number of interviews offered and attended. Some demographics had varying USMLE Step 1 scores but similar match rates.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2020 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; May 2020. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/MM_Results_and-Data_2020-1.pdf

- Gauer JL, Jackson JB. The association of USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores with residency match specialty and location. Med Educ Online. 2017;22:1358579.

- Wang JV, Keller M. Pressure to publish for residency applicants in dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt56x1t7ww.

- Wang RF, Zhang M, Kaffenberger JA. Does the dermatology standardized letter of recommendation alter applicants’ chances of matching into residency. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:e139-e140.

- National Resident Matching Program, Data Release and Research Committee: results of the 2018 NRMP Program Director Survey. Accessed December 19, 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/NRMP-2018-Program-Director-Survey-for-WWW.pdf

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role of race and ethnicity in the dermatology applicant match process. J Natl Med Assoc. 2022;113:666-670.

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants-turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Van Voorhees AS, Enos CW. Diversity in dermatology residency programs. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S46-S49.

- National Resident Matching Program. Charting outcomes in the match: U.S. allopathic seniors. Characteristics of U.S. allopathic seniors who matched to their preferred specialty in the 2018 main residency match. 2nd ed. Accessed December 19, 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2018_Seniors-1.pdf

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2020 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; May 2020. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/MM_Results_and-Data_2020-1.pdf

- Gauer JL, Jackson JB. The association of USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 CK scores with residency match specialty and location. Med Educ Online. 2017;22:1358579.

- Wang JV, Keller M. Pressure to publish for residency applicants in dermatology. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22:13030/qt56x1t7ww.

- Wang RF, Zhang M, Kaffenberger JA. Does the dermatology standardized letter of recommendation alter applicants’ chances of matching into residency. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:e139-e140.

- National Resident Matching Program, Data Release and Research Committee: results of the 2018 NRMP Program Director Survey. Accessed December 19, 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/NRMP-2018-Program-Director-Survey-for-WWW.pdf

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role of race and ethnicity in the dermatology applicant match process. J Natl Med Assoc. 2022;113:666-670.

- Chen A, Shinkai K. Rethinking how we select dermatology applicants-turning the tide. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:259-260.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Van Voorhees AS, Enos CW. Diversity in dermatology residency programs. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S46-S49.

- National Resident Matching Program. Charting outcomes in the match: U.S. allopathic seniors. Characteristics of U.S. allopathic seniors who matched to their preferred specialty in the 2018 main residency match. 2nd ed. Accessed December 19, 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2018_Seniors-1.pdf

PRACTICE POINTS

- Dermatology residency continues to be one of the most competitive specialties, with a match rate of 84.7% in 2019.

- A high US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score and having a home dermatology program and a greater number of interviews may lead to higher likeliness of matching in dermatology.

- Most applicants (82.4%) applied to programs their partner had interviews at, suggesting this may be a helpful strategy.

Forceps for Milia Extraction

To the Editor:

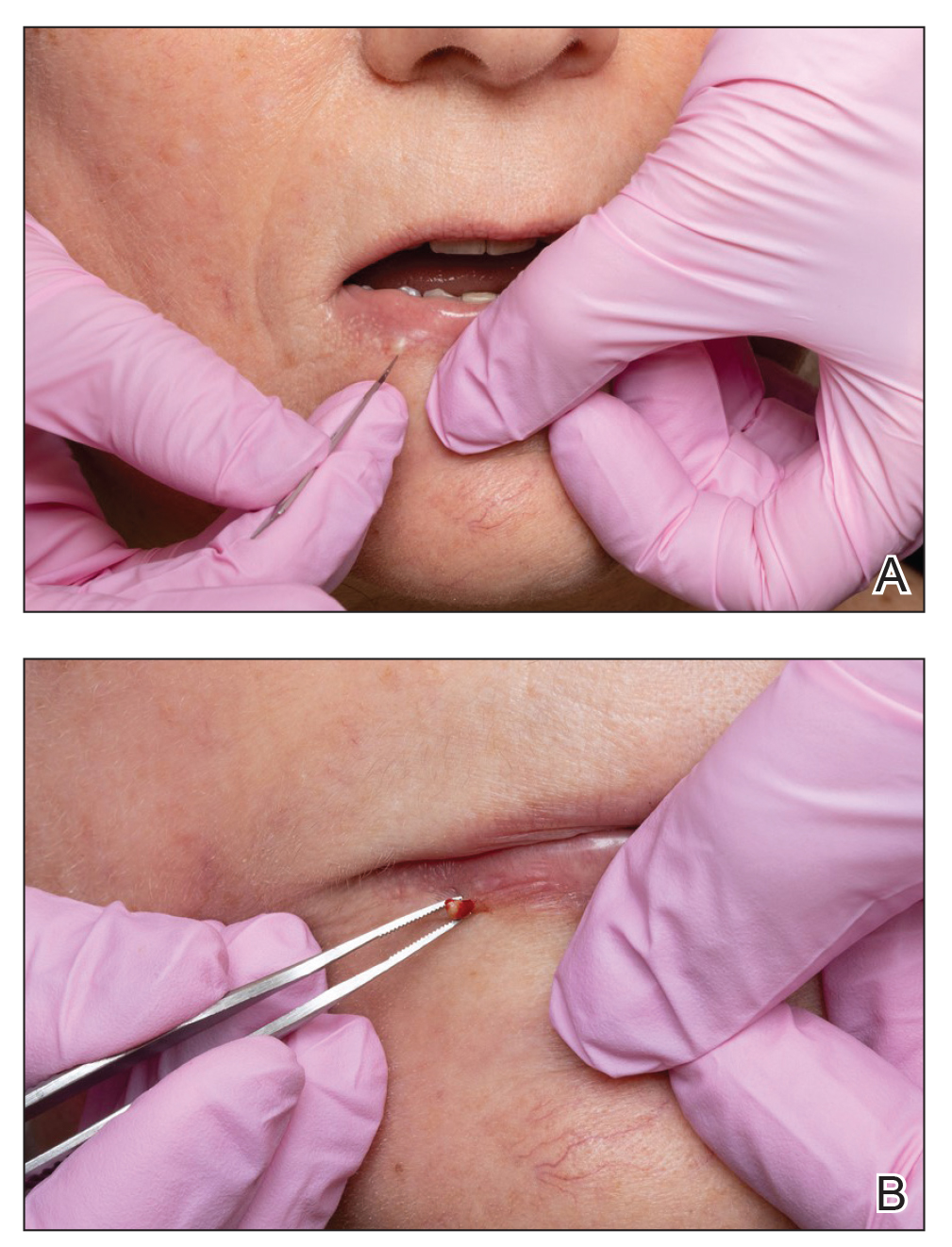

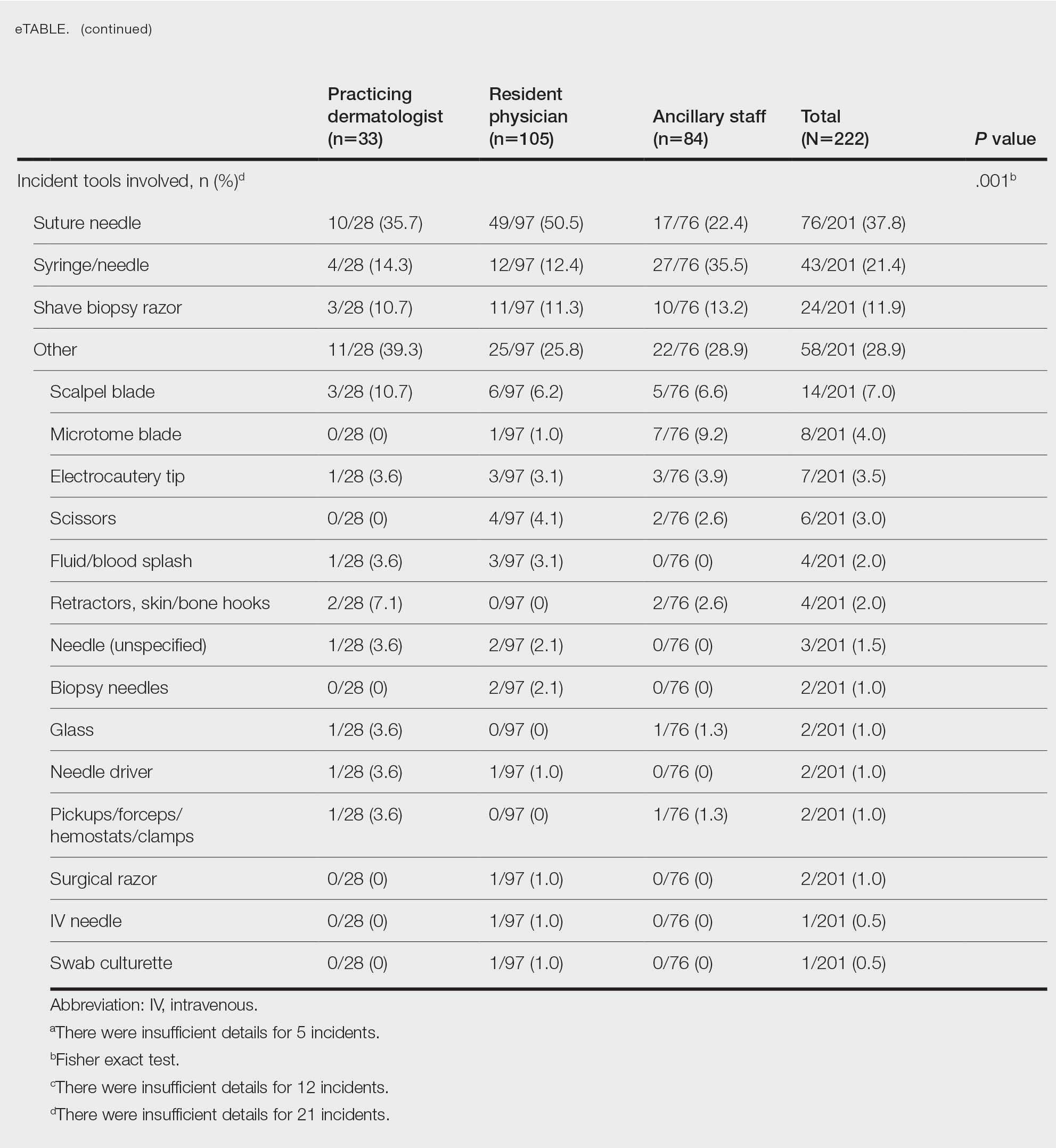

Several techniques can be used to destroy milia including electrocautery, electrodesiccation, and laser therapy. Manual extraction of milia uses a scalpel blade, needle, or stylet followed by the application of pressure to the lesion with a curette, comedone extractor, paper clip, cotton-tipped applicator, tongue blade, or hypodermic needle.1-4 Many of these techniques fail to stabilize milia, particularly in sensitive areas such as around the eyes or mouth, which can make extraction challenging, inefficient, and painful for the patient. We report a novel technique that quickly and effectively removes milia with equipment commonly used in the practice of clinical dermatology.

A 74-year-old woman presented with an asymptomatic papule on the right lower vermilion border of several years' duration. Physical examination of the lesion revealed a 3-mm, firm, white, dome-shaped papule. Clinical features were most consistent with a benign acquired milium. The patient desired removal for cosmesis. The area was cleaned with an alcohol swab, the surface of the milium was nicked with a No. 11 blade (Figure, A), and then tips of nontoothed Adson forceps were used to gently secure and pinch the base of the papule (Figure, B). The intact cyst was quickly and effortlessly expressed through the epidermal nick. The patient tolerated the procedure well, experiencing minimal pain and bleeding.

Histologically, milia represent infundibular keratin-filled cysts lined with stratified squamous epithelial tissue that contains a granular cell layer. These lesions are classified as primary or secondary; the former represent spontaneous occurrence, and the latter are associated with medications, trauma, or genodermatoses.2 Multiple milia are associated with conditions such as Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome, Rombo syndrome, Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, oro-facial-digital syndrome type I, atrichia with papular lesions, pachyonychia congenita type 2, basal cell nevus syndrome, basaloid follicular hamartoma syndrome, and hereditary vitamin D–dependent rickets type 2.5-9 The most common subtype seen in clinical practice includes benign primary milia, which tends to favor the cheeks and eyelids.2

Although these lesions are benign, many patients seek extraction for cosmesis. Milia extraction is a common procedure performed in dermatology clinical practice. Proposed extraction techniques using destructive methods include electrocautery, electrodesiccation, and laser therapy, and manual methods include nicking the surface of the lesion with a scalpel blade, needle, or stylet and then applying tangential pressure with a curette, comedone extractor, paper clip, cotton-tipped applicator, tongue blade, or hypodermic needle.1-4 Topical retinoids have been proposed as treatment of multiple milia.10 Many of these techniques do not use equipment common to clinical practice, or they fail to stabilize milia in sensitive areas, which makes extraction challenging. We describe a case with a new manual technique that successfully extracts milia in an efficient and safe manner.

- Parlette HL III. Management of cutaneous cysts. In: Wheeland RG, ed. Cutaneous Surgery. WB Saunders; 1994:651-652.

- Berk DR, Bayliss SJ. Milia: a review and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:1050-1063.

- George DE, Wasko CA, Hsu S. Surgical pearl: evacuation of milia with a paper clip. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:326.

- Thami GP, Kaur S, Kanwar AJ. Surgical pearl: enucleation of milia with a disposable hypodermic needle. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:602-603.

- Goeteyn M, Geerts ML, Kint A, et al. The Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:337-342.

- Michaëlsson G, Olsson E, Westermark P. The Rombo syndrome: a familial disorder with vermiculate atrophoderma, milia, hypotrichosis, trichoepitheliomas, basal cell carcinomas and peripheral vasodilation with cyanosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1981;61:497-503.

- Gurrieri F, Franco B, Toriello H, et al. Oral-facial-digital syndromes: review and diagnostic guidelines. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:3314-3323.

- Zlotogorski A, Panteleyev AA, Aita VM, et al. Clinical and molecular diagnostic criteria of congenital atrichia with papular lesions. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:1662-1665.

- Paller AS, Moore JA, Scher R. Pachyonychia congenita tarda. alate-onset form of pachyonychia congenita. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:701-703.

- Connelly T. Eruptive milia and rapid response to topical tretinoin. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:816-817.

To the Editor:

Several techniques can be used to destroy milia including electrocautery, electrodesiccation, and laser therapy. Manual extraction of milia uses a scalpel blade, needle, or stylet followed by the application of pressure to the lesion with a curette, comedone extractor, paper clip, cotton-tipped applicator, tongue blade, or hypodermic needle.1-4 Many of these techniques fail to stabilize milia, particularly in sensitive areas such as around the eyes or mouth, which can make extraction challenging, inefficient, and painful for the patient. We report a novel technique that quickly and effectively removes milia with equipment commonly used in the practice of clinical dermatology.