User login

Is DXA Valid for Kidney Patients?

Q) A 53-year-old dialysis patient in my clinic says her nephrologist told her she did not need a DXA scan because it was not valid for kidney patients. Why not?

Osteoporosis is a condition of reduced bone mass, causing decreased bone strength and leading to increased risk for fractures. The World Health Organization definition of osteoporosis is based on bone mineral density (BMD). While there is some overlap between idiopathic osteoporosis and chronic kidney disease–mineral bone disorder (CKD-MBD), both conditions have different pathophysiologic backgrounds and require different treatments.1

There is not an accurate correlation between BMD as measured by DXA and the type of CKD-associated bone disease.2 Patients with CKD typically have lower bone density than the general population, making the interpretation of DXA (dual x-ray absorptiometry) scans more complicated. This is due to focal areas of osteosclerosis, the presence of extraskeletal calcifications, and the variable presence of osteomalacia.

The gold standard for assessment and diagnosis of bone disease in CKD patients is the iliac crest bone biopsy. However, it is not frequently performed due to the painful and invasive nature of the procedure and the limitations in access to centers where it is performed and to experienced pathologists.

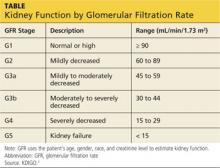

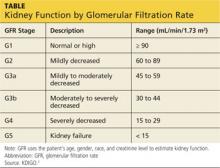

KDIGO (Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes) guidelines3 recommend that in patients with CKD stages 3 to 5D (see chart for explanation), measurements of serum parathyroid hormone or bone-specific alkaline phosphatase be used to evaluate bone disease, because markedly high or low values predict underlying bone turnover.

Shelly Levinstein, MSN, CRNP

Nephrology Associates of York

York, PA

REFERENCES

1. Toussaint N, Elder G, Kerr P. Bisphosphonates in chronic kidney disease; balancing potential benefits and adverse effects on bone and soft tissue. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:221-233.

2. Tanenbaum N, Quarles LD. Bone disorders in chronic kidney disease. In: Greenberg A, Cheung AK, eds. Primer on Kidney Diseases. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2009:487-498.

3. Moe S, Drueke T, Cunningham J, et al; Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Definition, evaluation, and classification of renal osteodystrophy: a position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2006;69:1945-1953.

4. Gilbert S, Weiner DE. National Kidney Foundation’s Primer on Kidney Diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:330.

Q) A 53-year-old dialysis patient in my clinic says her nephrologist told her she did not need a DXA scan because it was not valid for kidney patients. Why not?

Osteoporosis is a condition of reduced bone mass, causing decreased bone strength and leading to increased risk for fractures. The World Health Organization definition of osteoporosis is based on bone mineral density (BMD). While there is some overlap between idiopathic osteoporosis and chronic kidney disease–mineral bone disorder (CKD-MBD), both conditions have different pathophysiologic backgrounds and require different treatments.1

There is not an accurate correlation between BMD as measured by DXA and the type of CKD-associated bone disease.2 Patients with CKD typically have lower bone density than the general population, making the interpretation of DXA (dual x-ray absorptiometry) scans more complicated. This is due to focal areas of osteosclerosis, the presence of extraskeletal calcifications, and the variable presence of osteomalacia.

The gold standard for assessment and diagnosis of bone disease in CKD patients is the iliac crest bone biopsy. However, it is not frequently performed due to the painful and invasive nature of the procedure and the limitations in access to centers where it is performed and to experienced pathologists.

KDIGO (Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes) guidelines3 recommend that in patients with CKD stages 3 to 5D (see chart for explanation), measurements of serum parathyroid hormone or bone-specific alkaline phosphatase be used to evaluate bone disease, because markedly high or low values predict underlying bone turnover.

Shelly Levinstein, MSN, CRNP

Nephrology Associates of York

York, PA

REFERENCES

1. Toussaint N, Elder G, Kerr P. Bisphosphonates in chronic kidney disease; balancing potential benefits and adverse effects on bone and soft tissue. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:221-233.

2. Tanenbaum N, Quarles LD. Bone disorders in chronic kidney disease. In: Greenberg A, Cheung AK, eds. Primer on Kidney Diseases. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2009:487-498.

3. Moe S, Drueke T, Cunningham J, et al; Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Definition, evaluation, and classification of renal osteodystrophy: a position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2006;69:1945-1953.

4. Gilbert S, Weiner DE. National Kidney Foundation’s Primer on Kidney Diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:330.

Q) A 53-year-old dialysis patient in my clinic says her nephrologist told her she did not need a DXA scan because it was not valid for kidney patients. Why not?

Osteoporosis is a condition of reduced bone mass, causing decreased bone strength and leading to increased risk for fractures. The World Health Organization definition of osteoporosis is based on bone mineral density (BMD). While there is some overlap between idiopathic osteoporosis and chronic kidney disease–mineral bone disorder (CKD-MBD), both conditions have different pathophysiologic backgrounds and require different treatments.1

There is not an accurate correlation between BMD as measured by DXA and the type of CKD-associated bone disease.2 Patients with CKD typically have lower bone density than the general population, making the interpretation of DXA (dual x-ray absorptiometry) scans more complicated. This is due to focal areas of osteosclerosis, the presence of extraskeletal calcifications, and the variable presence of osteomalacia.

The gold standard for assessment and diagnosis of bone disease in CKD patients is the iliac crest bone biopsy. However, it is not frequently performed due to the painful and invasive nature of the procedure and the limitations in access to centers where it is performed and to experienced pathologists.

KDIGO (Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes) guidelines3 recommend that in patients with CKD stages 3 to 5D (see chart for explanation), measurements of serum parathyroid hormone or bone-specific alkaline phosphatase be used to evaluate bone disease, because markedly high or low values predict underlying bone turnover.

Shelly Levinstein, MSN, CRNP

Nephrology Associates of York

York, PA

REFERENCES

1. Toussaint N, Elder G, Kerr P. Bisphosphonates in chronic kidney disease; balancing potential benefits and adverse effects on bone and soft tissue. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:221-233.

2. Tanenbaum N, Quarles LD. Bone disorders in chronic kidney disease. In: Greenberg A, Cheung AK, eds. Primer on Kidney Diseases. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2009:487-498.

3. Moe S, Drueke T, Cunningham J, et al; Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Definition, evaluation, and classification of renal osteodystrophy: a position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2006;69:1945-1953.

4. Gilbert S, Weiner DE. National Kidney Foundation’s Primer on Kidney Diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:330.

How to Treat Bone Loss in Kidney Patients

Q) Since bone loss is common in patients with kidney disease, how should it be treated?

In elderly CKD patients, it is recognized that osteoporosis and CKD-MBD may co-exist—which only makes the bone-loss issue more problematic. Therefore, diagnosis and management are crucial to effective treatment.

Although osteoporosis is recognized and treated in CKD stages 1 to 3a, the interpretation of BMD levels in the osteoporotic range is controversial in advanced kidney disease (GFR < 35).1 There are limited data for treatment of patients with CKD-MBD.

Studies of bisphosphonate use in postmenopausal women and in patients with glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis have generally excluded those with renal impairment. For these patients, treatment of low BMD using standard therapies for osteoporosis is not without potential for harm, due to the possibility of worsening low bone turnover, osteomalacia, mixed uremic osteodystrophy, and exacerbated hyperparathyroidism.

The choice of pharmaceutical treatment should be based on whether you are treating CKD-MBD or osteoporosis. A large percentage of CKD patients have adynamic bone disease with low bone resorption. In patients with low bone resorption, treatment entails choosing a drug that stimulates bone formation and not those that inhibit bone resorption. The benefit of bisphosphonate therapy is seen in patients with high bone resorption.4

In CKD stages 1 to 3, one must evaluate laboratory features of low BMD, including serum levels of calcium, phosphate, parathyroid hormone, alkaline phosphatase, and vitamin D. If all are found to be normal, bisphosphonate use in CKD stages 1 to 3 is usually safe.1

A bone biopsy is recommended for patients with advanced CKD stages 4 to 5/5D, with therapy individualized per disease process.1

Shelly Levinstein, MSN, CRNP

Nephrology Associates of York

York, PA

REFERENCES

1. Toussaint N, Elder G, Kerr P. Bisphosphonates in chronic kidney disease; balancing potential benefits and adverse effects on bone and soft tissue. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:221-233.

2. Tanenbaum N, Quarles LD. Bone disorders in chronic kidney disease. In: Greenberg A, Cheung AK, eds. Primer on Kidney Diseases. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2009:487-498.

3. Moe S, Drueke T, Cunningham J, et al; Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Definition, evaluation, and classification of renal osteodystrophy: a position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2006;69:1945-1953.

4. Gilbert S, Weiner DE. National Kidney Foundation’s Primer on Kidney Diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:330.

Q) Since bone loss is common in patients with kidney disease, how should it be treated?

In elderly CKD patients, it is recognized that osteoporosis and CKD-MBD may co-exist—which only makes the bone-loss issue more problematic. Therefore, diagnosis and management are crucial to effective treatment.

Although osteoporosis is recognized and treated in CKD stages 1 to 3a, the interpretation of BMD levels in the osteoporotic range is controversial in advanced kidney disease (GFR < 35).1 There are limited data for treatment of patients with CKD-MBD.

Studies of bisphosphonate use in postmenopausal women and in patients with glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis have generally excluded those with renal impairment. For these patients, treatment of low BMD using standard therapies for osteoporosis is not without potential for harm, due to the possibility of worsening low bone turnover, osteomalacia, mixed uremic osteodystrophy, and exacerbated hyperparathyroidism.

The choice of pharmaceutical treatment should be based on whether you are treating CKD-MBD or osteoporosis. A large percentage of CKD patients have adynamic bone disease with low bone resorption. In patients with low bone resorption, treatment entails choosing a drug that stimulates bone formation and not those that inhibit bone resorption. The benefit of bisphosphonate therapy is seen in patients with high bone resorption.4

In CKD stages 1 to 3, one must evaluate laboratory features of low BMD, including serum levels of calcium, phosphate, parathyroid hormone, alkaline phosphatase, and vitamin D. If all are found to be normal, bisphosphonate use in CKD stages 1 to 3 is usually safe.1

A bone biopsy is recommended for patients with advanced CKD stages 4 to 5/5D, with therapy individualized per disease process.1

Shelly Levinstein, MSN, CRNP

Nephrology Associates of York

York, PA

REFERENCES

1. Toussaint N, Elder G, Kerr P. Bisphosphonates in chronic kidney disease; balancing potential benefits and adverse effects on bone and soft tissue. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:221-233.

2. Tanenbaum N, Quarles LD. Bone disorders in chronic kidney disease. In: Greenberg A, Cheung AK, eds. Primer on Kidney Diseases. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2009:487-498.

3. Moe S, Drueke T, Cunningham J, et al; Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Definition, evaluation, and classification of renal osteodystrophy: a position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2006;69:1945-1953.

4. Gilbert S, Weiner DE. National Kidney Foundation’s Primer on Kidney Diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:330.

Q) Since bone loss is common in patients with kidney disease, how should it be treated?

In elderly CKD patients, it is recognized that osteoporosis and CKD-MBD may co-exist—which only makes the bone-loss issue more problematic. Therefore, diagnosis and management are crucial to effective treatment.

Although osteoporosis is recognized and treated in CKD stages 1 to 3a, the interpretation of BMD levels in the osteoporotic range is controversial in advanced kidney disease (GFR < 35).1 There are limited data for treatment of patients with CKD-MBD.

Studies of bisphosphonate use in postmenopausal women and in patients with glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis have generally excluded those with renal impairment. For these patients, treatment of low BMD using standard therapies for osteoporosis is not without potential for harm, due to the possibility of worsening low bone turnover, osteomalacia, mixed uremic osteodystrophy, and exacerbated hyperparathyroidism.

The choice of pharmaceutical treatment should be based on whether you are treating CKD-MBD or osteoporosis. A large percentage of CKD patients have adynamic bone disease with low bone resorption. In patients with low bone resorption, treatment entails choosing a drug that stimulates bone formation and not those that inhibit bone resorption. The benefit of bisphosphonate therapy is seen in patients with high bone resorption.4

In CKD stages 1 to 3, one must evaluate laboratory features of low BMD, including serum levels of calcium, phosphate, parathyroid hormone, alkaline phosphatase, and vitamin D. If all are found to be normal, bisphosphonate use in CKD stages 1 to 3 is usually safe.1

A bone biopsy is recommended for patients with advanced CKD stages 4 to 5/5D, with therapy individualized per disease process.1

Shelly Levinstein, MSN, CRNP

Nephrology Associates of York

York, PA

REFERENCES

1. Toussaint N, Elder G, Kerr P. Bisphosphonates in chronic kidney disease; balancing potential benefits and adverse effects on bone and soft tissue. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:221-233.

2. Tanenbaum N, Quarles LD. Bone disorders in chronic kidney disease. In: Greenberg A, Cheung AK, eds. Primer on Kidney Diseases. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2009:487-498.

3. Moe S, Drueke T, Cunningham J, et al; Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Definition, evaluation, and classification of renal osteodystrophy: a position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2006;69:1945-1953.

4. Gilbert S, Weiner DE. National Kidney Foundation’s Primer on Kidney Diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:330.