User login

Depressive Symptoms and Readmission

Unplanned hospital readmission within 30 days is an important marker of the quality of care provided in the hospital and in the immediate posthospital setting.[1] In the United States, 1 in 5 Medicare patients is readmitted within 30 days, and related Medicare costs are estimated to be $17 billion annually.[2] Public policy is attempting to drive down healthcare costs in the United States via the Affordable Care Act by reducing payments to hospitals that have high 30‐day readmission rates.[3]

The prevalence of depression is 6.7% of adults,[4] and depressive symptomatology has been linked to hospital readmission.[5, 6] Depressive symptoms are associated with poor health outcomes and increased utilization. Patients with cardiac disease and depressive symptoms have worse outcomes.[7] Mild symptoms are associated with increased primary care and mental health care visits.[8] Both mild and moderate‐to‐severe depressive symptomatology are associated with symptom burden, physical limitation, quality of life, and overall health.[9] Importantly, many hospitalized patients, who do not have a diagnosis of depression, display depressive symptomatology.[10] A gap in knowledge exists as to the utility of stratifying depressive symptomatology between mild and moderate to severe in determining risk for hospital readmission.

Although the causal pathway to worse outcomes in patients with a diagnosis of depression has been studied,[11] the reasons for poor outcomes of patients with depressive symptomatology have not been well described, particularly in hospitalized general medical patients. Nonadherence to physician recommendations, decreased cognitive function, and poor adherence to self‐care recommendations[12, 13, 14] may explain increased healthcare utilization. Physiological models hypothesize heightened levels of proinflammatory markers[15, 16] and vascular depression[17] may play a role. There remains a gap in knowledge as to the postdischarge utilization of hospitalized patients with depressive symptomatology.

We studied the rate of hospital readmission among hospitalized adult patients with mild and moderate‐to‐severe depressive symptoms as defined by the 9‐Item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ‐9) depression screening tool.[18]

METHODS

Setting, Data, and Participants

Data from 2 Project Re‐Engineered Discharge (RED) clinical trials were included in a secondary analysis.[19, 20, 21] Depressive symptom screening data were available for 1418 participants originally randomized to the control and experimental groups in each trial.

The Project RED trials were a set of 2‐armed randomized controlled trials studying hospital utilization following a standardized hospital‐based discharge process. Inclusion criteria included English‐speaking patients who were 18 years or older and admitted to the adult medical service at Boston Medical Center, a large urban safety‐net hospital with an ethnically diverse patient population. Patients were required to have a telephone and have plans to return home after discharge. Patients were excluded if admitted from a skilled nursing facility or other hospital, transferred to a different hospital service before enrollment, admitted for a planned hospitalization, on hospital precautions, on suicide watch, or were deaf or blind. A full description of the methods has been described.[19] The second RED trial differed in that a health information technology system was used to teach the discharge plan to subjects at the time of discharge rather than a nurse.[20, 21]

The institutional review board of Boston University approved all study activities.

Outcome Variables

The primary end point for this analysis was the hospital readmission rate, defined as the total number of readmissions per subject within 30 days of the index discharge. Data were collected by hospital electronic medical record (EMR) review and by contacting subjects by telephone 30 days after discharge. Research staff collected data and were blinded to study group assignment. We examined emergency department (ED) utilization and primary care physician (PCP) follow‐up visit attendance rates within 30 days of discharge. Any ED or ambulatory visit resulting in hospital admission within 30 days of the index discharge date was counted as 1 readmission. Readmission and ED utilization dates occurring at Boston Medical Center were obtained from its EMR, whereas those at other hospitals were collected through subject report.

Primary Independent Variable

The primary independent variable was the PHQ‐9 screening questionnaire score, designed to identify patients with depressive symptoms. Data were collected at the time of enrollment during the index admission. Symptoms were categorized into 3 groups: no depression (PHQ‐9 score of 04, or less than a score of 2 on the first 2 questions of the PHQ‐9), mild depressive symptoms (PHQ‐9 score of 59), and moderate‐to‐severe symptoms (PHQ‐9 score of 1027).[18]

Statistical Analysis

Potential confounders were identified a priori from available literature on factors associated with hospital readmission. These included age,[22] race, gender,[23] marital status, health literacy (using the Rapid Estimate of Health Literacy in Adult Medicine [REALM] tool),[24] insurance type, employment status, income level,[25] Charlson Comorbidity Index,[26] homelessness within the past 3 months, hospital utilization within the 6 months before the index hospitalization,[27] educational attainment, length of hospital stay,[28] and study group assignment.

Demographic and other characteristics were compared by dichotomized healthcare reutilization outcomes using bivariate analysis to identify potential confounders of the relationship between depressive symptom severity and hospital readmission. [2] tests were used for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. Age (years) and length of stay (days) were used as continuous variables. Gender (male/female), frequent hospital admission within 6 months (01 vs 2 or more), homelessness, and presence of substance use disorder diagnosis (defined by the International Statistical Classification of Disease, 9th Revision [ICD‐9] diagnosis codes, which included 303.0 [alcohol dependence], 305.0 [alcohol abuse], 291.0 [alcohol‐induced mental disorders], 304.0 [drug dependence], 305.2305.7, 305.9 [drug abuse] and 292.0 [drug‐induced mental disorders]) were treated as dichotomous variables. Categorical variables were created for marital status (single, married, divorced/widowed), educational attainment (less than or incomplete high school, high school graduate, some college, college graduate), insurance type (Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, or Free Care), income level (<$19,999 per year, $20,00039,000, $40,00074,999, >$75,000, or unknown/refused to answer), employment status (working full time, working part time, not working, or no answer), and health literacy level according to REALM score (044 [grade 6 or below], 4560 [grade 78], or 6166 [grade 9 or above]).

The readmission rate reflects the number of hospital readmission events per subject within 30 days of discharge. The PCP follow‐up rate reflects the number of subjects attending a posthospital PCP visit within 30 days of discharge. The incidence rate ratio (IRR) was calculated to compare the rates of readmission between those with mild, moderate to severe, and no depressive symptoms. Readmission data at 30 days are cumulative. Poisson models were used to test for significant differences between the predicted and observed number of events at 30 days. A stepwise selection process (with =0.2 as entry and exit criteria) was conducted to identify relevant confounders and to construct the final model for the association between depressive symptom screen severity and readmission. Using sensitivity analysis, we tested a model including substance abuse as a variable. This did not substantially change our final model, and therefore we did not include this variable in the final model.

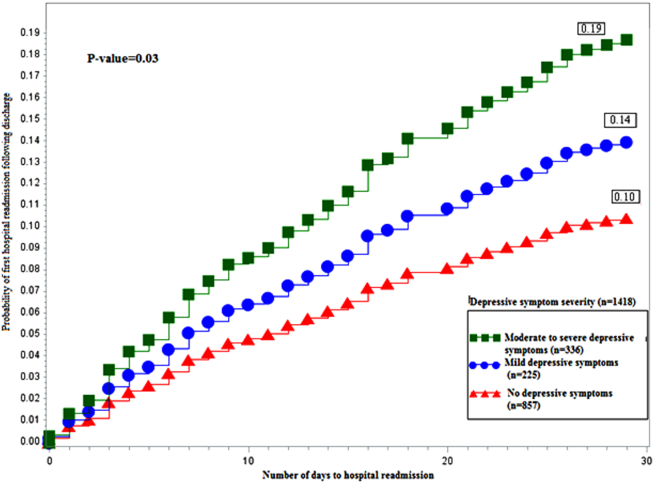

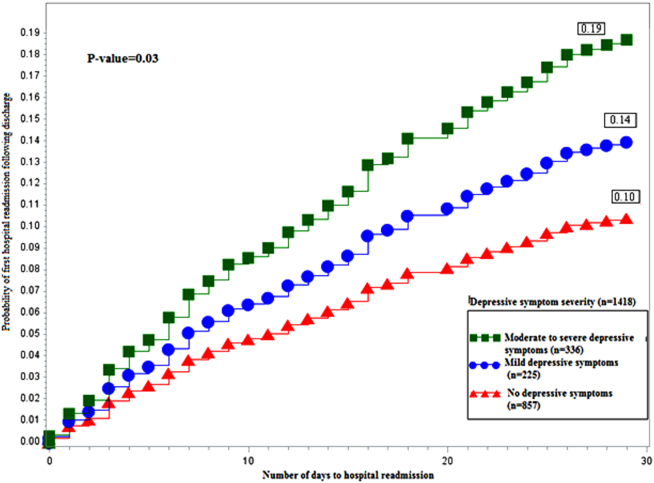

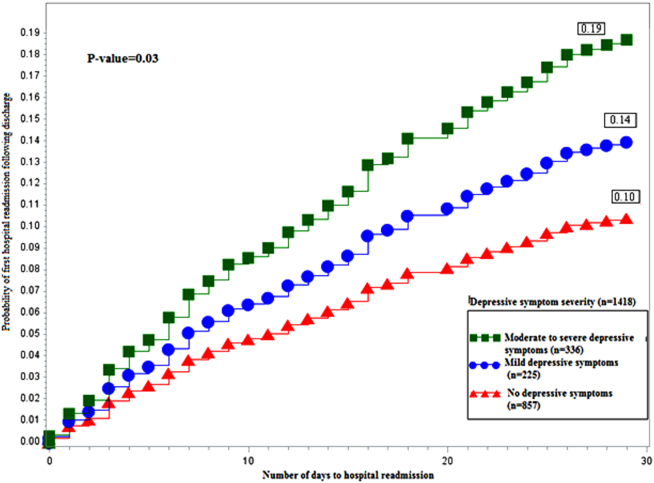

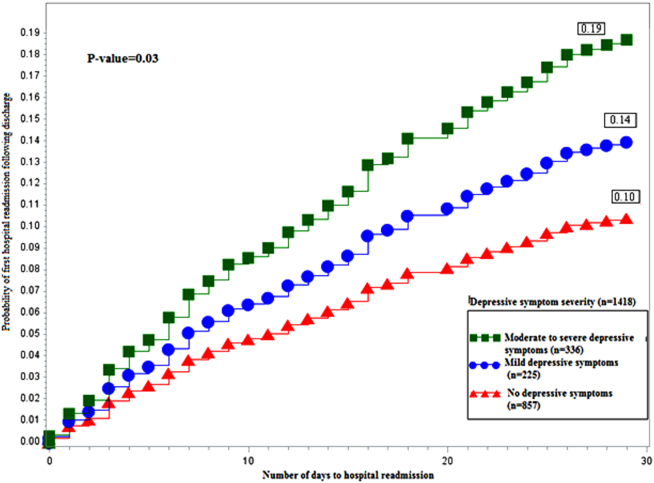

A Kaplan‐Meier hazard curve was generated for time from the index discharge to the first hospital readmission within 30 days. The hazard of readmission was compared among the 3 depressive symptom screen categories using Cox proportional hazards. Two‐sided significance tests were used. P values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All data were analyzed with SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Adjusted Poisson regression results identified individuals with readmission and/or ED utilization rates much higher than the sample mean. Data points with 5 or more hospital readmissions or 7 or more combined readmissions and ED utilizations were removed from analysis.

RESULTS

Of the total study population, 15.9% (225/1418) demonstrated mild depressive symptoms, and 23.7% (336/1418) demonstrated moderate‐to‐severe symptoms. Of those in our study, 38.9% (551/1418) self‐reported being told by a healthcare professional that they had depression. Of those self‐reporting depression, 27.9% (273/540) were currently taking antidepressant medication at the time of the index hospitalization. Table 1 shows baseline characteristics by dichotomized utilization outcome. Mean age, marital status, health insurance, employment status, mean length of stay, admissions in the previous 6 months, mean Charlson score, and substance abuse were significantly associated with hospital readmission. Of these characteristics, all but mean length of stay and previous history of substance abuse were significantly associated with ED utilization.

| Hospital Readmission | ED Utilization | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, n=1,240 | Yes, n=193 | No, n=1,231 | Yes, n=202 | |

| ||||

| Male, n (%) | 602 (48.6) | 105 (54.4) | 606 (49.3) | 101 (50.0) |

| Mean age, y (SD) | 49.14 (14.21)a | 52.24 (14.69)a | 50.06 (14.57)a | 46.45 (12.19)a |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White non‐Hispanic | 332 (26.8) | 73 (37.8) | 357 (29.0) | 48 (23.8) |

| Black non‐Hispanic | 666 (53.7) | 89 (46.1) | 646 (52.5) | 109 (54.0) |

| Hispanic | 135 (10.9) | 19 (9.8) | 124 (10.1) | 30 (14.9) |

| Other or mixed race | 59 (4.8) | 7 (3.6) | 56 (4.6) | 10 (5.0) |

| Unknown | 48 (3.9) | 5 (2.6) | 48 (3.9) | 5 (2.5) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||

| Single | 593 (47.8)a | 74 (38.3)a | 552 (44.8)a | 115 (56.9)a |

| Married | 286 (23.1)a | 42 (21.8)a | 296 (24.1)a | 32 (15.8)a |

| Divorced/widowed | 346 (27.9)a | 74 (38.3)a | 369 (20.0)a | 51 (25.3)a |

| Unknown | 15 (1.2)a | 3 (1.6)a | 14 (1.1)a | 4 (2.0)a |

| Annual personal income, n (%) | ||||

| <$19,999 | 511 (41.2) | 88 (45.6) | 509 (41.4) | 90 (44.6) |

| $20,000$39,999 | 184 (14.8) | 22 (11.4) | 175 (14.2) | 31 (15.4) |

| $40,000$74,999 | 107 (8.6) | 14 (7.3) | 111 (9.0) | 10 (5.0) |

| >$75,000 | 41 (3.3) | 8 (4.2) | 44 (3.6) | 5 (2.5) |

| Unknown/refused | 397 (32.0) | 61 (31.6) | 392 (31.8) | 66 (32.7) |

| Health insurance, n (%) | ||||

| Private | 321 (25.9)a | 34 (17.6)a | 316 (25.7)a | 39 (19.3)a |

| Medicaid | 510 (41.1)a | 90 (46.6)a | 485 (39.4)a | 115 (56.9)a |

| Medicare | 138 (11.1)a | 43 (22.3)a | 170 (13.8)a | 11 (5.5)a |

| Free Care | 207 (16.7)a | 14 (7.3)a | 190 (15.4)a | 31 (15.4)a |

| Other/unknown | 64 (5.2)a | 12 (6.2)a | 70 (5.7)a | 6 (3.0)a |

| Education level, n (%) | ||||

| Incomplete high school | 290 (23.4) | 45 (23.3) | 288 (23.4) | 47 (23.3) |

| High school graduate/GED | 492 (39.7) | 87 (45.1) | 489 (39.7) | 90 (44.6) |

| Some college | 257 (20.7) | 34 (17.6) | 255 (20.7) | 36 (17.8) |

| College degree | 183 (14.8) | 25 (13.0) | 183 (14.9) | 25 (12.4) |

| Unknown | 18 (1.5) | 2 (1.0) | 16 (1.3) | 4 (2.0) |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||||

| Full time | 322 (26.4)a | 31 (16.6)a | 316 (26.2)a | 37 (18.7)a |

| Part time | 136 (11.2)a | 11 (5.9)a | 124 (10.3)a | 23 (11.6)a |

| Retired | 172 (14.1)a | 37 (19.8)a | 196 (16.2)a | 13 (6.6)a |

| Disabled | 278 (22.8)a | 72 (38.5)a | 287 (23.8)a | 63 (31.8)a |

| Unemployed | 286 (23.5)a | 31 (16.6)a | 258 (21.4)a | 59 (29.8)a |

| Student | 24 (2.0)a | 5 (2.7)a | 26 (2.2)a | 3 (1.5)a |

| Homeless in past 6 months, n (%) | 143 (11.6) | 24 (12.5) | 126 (10.3) | 41 (20.4) |

| Health literacy, n (%)b | ||||

| 6th‐grade level | 230 (19.2) | 41 (22.4) | 228 (19.2) | 43 (22.4) |

| 7th8th‐grade level | 342 (28.5) | 60 (32.8) | 342 (28.7) | 60 (31.3) |

| 9th‐grade level | 627 (52.3) | 82 (44.8) | 620 (52.1) | 89 (46.4) |

| Mean length of stay, d (SD) | 2.69 (2.60)a | 3.57 (3.50)a | 2.81 (2.80) | 2.84 (2.18) |

| PCP at enrollment, n (%)c | 1,005 (81.1) | 166 (86.0) | 1,005 (81.7) | 166 (82.2) |

| 2 Admissions in past 6 months, n (%) | 300 (24.2)a | 81 (42.0)a | 292 (23.7)a | 89 (44.1)a |

| Mean Charlson score (SD)d | 2.19 (2.53)a | 2.85 (2.78)a | 2.34 (2.60)a | 1.92 (2.18)a |

| Substance abuse, n (%)e | 138 (12.0)a | 36 (19.7)a | 151 (13.1) | 23 (12.6) |

Table 2 shows the unadjusted 30 day hospital readmission, ED utilization, and PCP follow‐up rates. Participants with mild symptoms had higher readmission rates than those without symptoms (0.20 vs 0.13). In other words, 20 readmissions occurred per 100 subjects with mild symptoms, compared with 13 readmissions per 100 subjects without symptoms (P<0.001). The readmission rate was 0.21 for subjects with moderate‐to‐severe depression. The rate of ED utilization for subjects with mild symptoms was 0.18. This was significantly different from ED utilization rates of those with no depression and those with moderate‐to‐severe symptoms, which were 0.16 and 0.28, respectively (P<0.001). The postdischarge follow‐up rates were different for those without depression compared to those with mild and moderate‐to‐severe symptoms (58.7, 49.5, and 51.1, respectively), but this did not reach statistical significance (P=0.06).

| Depressive Symptom Severity Based on PHQ‐9 Score, N=1,418 | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Depression, n=857 | Mild Depressive Symptoms, n=225 | Moderate‐to‐Severe Depressive Symptoms, n=336 | ||

| ||||

| Hospital readmission, n (rate per 100) | 108 (12.6) | 44 (19.6) | 71 (21.1) | <0.001 |

| ED utilization, n (rate per 100) | 133 (15.5) | 41 (18.2) | 94 (28.0) | <0.001 |

| PCP follow‐up, n (rate per 100) | 420 (58.7) | 103 (49.5) | 157 (51.1) | 0.06 |

Poisson analyses were conducted to control for potential confounding in the relationship between symptom severity and readmission or ED utilization (Table 3). Compared to subjects with no depression, the association between mild symptoms and readmission remained significant (adjusted IRR: 1.49; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.11‐2.00) after controlling for relevant confounders. For those with moderate‐to‐severe symptoms, the adjusted IRR was 1.96 (95% CI: 1.51‐2.49). When compared to those without depression, the adjusted IRR for ED reutilization was not found to be significant for those with mild symptoms (1.30; 95% CI: 0.96‐1.76) and significant for those participants with moderate‐to‐severe symptoms (1.48; 95% CI: 1.16‐1.89).

| Depressive Symptom Severity Based on PHQ‐9 Score, N=1418 | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Depression, n=857 | Mild Depressive Symptoms, n=225 | Moderate‐to‐Severe Depressive Symptoms, n=336 | ||

| ||||

| Hospital readmission, n (rate per 100) | 96 (11.9) | 36 (17.1) | 67 (21.1) | <0.001 |

| Hospital readmission IRR (95% CI) | Ref | 1.49 (1.11‐2.00) | 1.96 (1.51‐2.49) | |

| ED utilization, n (rate per 100) | 124 (15.2) | 40 (19.0) | 85 (26.7) | 0.007 |

| ED utilization IRR (95% CI) | Ref | 1.30 (0.96‐1.76) | 1.48 (1.16‐1.89) | |

Figure 1 depicts the hazard curve generated for the time to first hospital readmission, stratified by depressive symptom severity. A readmission within 30 days following an index discharge date occurred in 10% of participants without depression, 14% of those with mild symptoms, and 19% of those with moderate‐to‐severe symptoms (P=0.03).

DISCUSSION

Our study shows hospitalized medical patients at an urban academic hospital with a positive screen for depressive symptoms are significantly more likely to be readmitted within 30 days of discharge as compared to those who do not screen positive. The significant association of depressive symptoms and readmission remains even after stratifying by severity and controlling for relevant confounders. Further, there appears to be a dose‐response relationship between depressive symptom severity and readmission. This graded effect makes the distinction between mild and moderate‐to‐severe depressive symptoms a better instrument at predicting rehospitalization than a diagnostic code for depression. Few studies have analyzed the readmission of general medical patients stratified by depressive symptomatology, and even fewer have addressed the presence of mild depressive symptomatology as it relates to readmission. A diagnosis of mild depression is associated with similar though less severe outcomes as compared to major depression, including negative effects on quality of life, functional disability, health status, and mortality.[29] Patients with heart failure and mild depressive symptoms have higher rates of readmission at 3 months and 1 year as compared with those without depressive symptoms, but these findings were not found to be significant.[30] Mild depressive symptoms may contribute to readmission, accrued medical cost, and burden of disease.

We extend previous research[5, 31, 32] by showing that, compared to those without and those with mild symptoms, the readmission risk is even greater for those who screen positive for moderate‐to‐severe symptoms. The mechanism linking depressive symptoms and readmission is not well understood. Behavioral mechanisms such as physical symptom amplification or anxiety about symptoms link depressive symptoms to healthcare utilization after discharge.[33] Depressive symptoms among patients with diabetes, asthma, hypertension, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) impairs medication adherence and self‐care behavior.[14, 34, 35, 36] Depressed patients might have reduced social support leading to increased stress, worsened symptoms, and prolonged recovery.[37] These mechanisms may prompt patients to present to hospitals for reevaluation. The direct physiologic consequences of depressive symptoms may be similar to that of the diagnosis of depression. Patients with cardiovascular disease and depression have poor outcomes, which may be related to decreased heart rate variability, hypercoagulability, high burden of inflammatory markers, and severity of left ventricular dysfunction.[38, 39] Among patients with HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and coronary artery disease, depression is linked to increased proinflammatory marker levels and less favorable outcomes, which may signal a more severe form of the disease or an impaired response to treatment.[15, 16]

Our data have several implications. Though disease burden may play a role in the presence of depressive symptomatology in hospitalized patients, screen‐positive patients still experienced more readmission events as compared to those without depressive symptoms after controlling for relevant confounders. Further, there appears to be a dose‐dependent relationship between depressive symptom severity and rate of readmission. Use of a categorical ICD‐9 code often implies that the diagnosis of depression has been confirmed. Rather than using administrative ICD‐9 codes to account for readmission risk, hospitals may consider screening patients for depressive symptoms during hospitalizations to both identify and risk‐stratify patients at high risk for readmission. Procedures should be implemented to address barriers to safe transitions in care in the screen‐positive population. The relationship between symptom severity and readmission rate may aid in the decision to devote resources to those at highest risk of readmission. Lastly, though research on the treatment of depressive symptoms in medical inpatients has been inconclusive in determining whether this approach is better than usual care or structured pharmacotherapies,[40] further study is needed to determine whether treatment of mild and moderate‐to‐severe depressive symptoms during an acute medical hospitalization will decrease readmission.

Strengths of the current study include the large dataset, the broad range of covariates available for analyses, and the inclusive nature of the sample, which was not restricted to factors such as age or medical condition.

Several limitations should be noted. We did not conduct a psychiatric evaluation to evaluate screen‐positive patients who met diagnostic criteria for minor or major depressive disorder, nor did we reconfirm the presence of symptoms at the time of or following hospital discharge. Our data, then, may not reflect patients' depressive symptomatology prior to the index hospitalization or at the time of discharge. Although such data might further refine the use of depressive symptomatology in identifying patients at high risk for readmission, our findings demonstrate that simply screening positive for depressive symptomatology at time of admission is associated with increased risk of readmission. We do not know the direction of the reported associations. If depressive symptoms are the consequence of higher disease burden, treatment of the underlying disease may be the most important intervention. Although this is possible, our model does include variables (eg, length of stay, Charlson Comorbidity Index), which are likely to adjust for disease severity, pointing to the likelihood that depressive symptoms truly predict hospital readmission independent of disease severity. Data on utilization outside Boston Medical Center (about 9% of outcomes) were determined by patient self‐report and not confirmed by document review. Our results may not be generalizable to populations other than those served by an urban safety‐net hospital or other populations excluded from analysis (eg, nonEnglish‐speaking patients, patients from nursing homes). Finally, social factors such as social support may residually confound the relationship between depressive symptom severity and readmission.

Our finding linking both mild and moderate‐to‐severe depressive symptoms to increased readmission when compared to those without depressive symptoms is significant for future policy. If future studies demonstrate that the initiation of treatment of patients who screen positive for depressive symptoms during an acute hospitalization leads to reduced readmission, policymakers should increase support for mental health screening and programming as an integral portion of general medical patient management.

In conclusion, screening positive for mild or moderate‐to‐severe depressive symptoms is associated with an increased rate of early hospital readmission as compared to those without depressive symptoms, even after controlling for relevant confounders. The rate and hazard of hospital readmission increase with symptom severity. This finding has important implications for future research for hospital screening programming and interventions for patients who screen positive for depressive symptoms.

Disclosures: This research was funded in part by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (NCT00252057) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NCT00217867). Dr. Cancino has been paid for consulting work for PracticeUpdate, a subsidiary of Elsevier. Dr. Culpepper has been paid for participation in advisory boards by AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly and Co., Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc., Forest Labs, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Jazz Pharmaceuticals plc, H. Lundbeck A/S, Merck & Co., Pfizer Inc., Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals Inc., Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc., and Takeda Pharmaceuticals Inc. He has received payment for educational presentations regarding hospital readmission without mention of any pharmaceutical or other products from Merck. Dr. Mitchell has received honoraria from Merck for lectures on health behavior counseling. Trial registration: NCT00252057, NCT00217867.

- , , , , . The association between the quality of inpatient care and early readmission: a meta‐analysis of the evidence. Med Care. 1997;35(10):1044–1059.

- , , . Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee‐for‐service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418–1428.

- Medicare program. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2012;77(170):53257–53750.

- , , , , . Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12‐month DSM‐IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–627.

- , , , et al. Post‐discharge hospital utilization among adult medical inpatients with depressive symptoms. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):378–384.

- , , , , . The association between depressive symptoms and non‐psychiatric hospitalisation in older adults. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e34821.

- , , , . Depressive symptoms and risk of functional decline and death in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38(1):199–205.

- , , , . Mental health conditions are associated with increased health care utilization among urban family medicine patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(5):398–407.

- , , , , , . Depressive symptoms and health‐related quality of life: the heart and soul study. JAMA. 2003;290(2):215–221.

- , , , , , . Major depressive disorder in hospitalized medically ill patients: an examination of young and elderly male veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(9):881–890.

- , . Single item on positive affect is associated with 1‐year survival in consecutive medical inpatients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(1):8–13.

- , , . The effect of depression on self‐care behaviors and quality of care in a national sample of adults with diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(5):422–427.

- , , , et al. The prevalence and correlates of major and minor depression in older medical inpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(8):1344–1353.

- , , , , . Depression is an important contributor to low medication adherence in hemodialyzed patients and transplant recipients. Kidney Int. 2009;75(11):1223–1229.

- , . Depression and immunity: inflammation and depressive symptoms in multiple sclerosis. Neurol Clin. 2006;24(3):507–519.

- , , , et al. Synergistic effects of psychological and immune stressors on inflammatory cytokine and sickness responses in humans. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23(2):217–224.

- , , , et al. Relationship between baseline white‐matter changes and development of late‐life depressive symptoms: 3‐year results from the LADIS study. Psychol Med. 2010;40(4):603–610.

- , , . The PHQ‐9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613.

- , , , et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):178–187.

- , , . Taking the time to care: empowering low health literacy hospital patients with virtual nurse agents. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery; 2009:1265–1274.

- , , , et al. Usability of conversational agents by patients with inadequate health literacy: evidence from two clinical trials. J Health Commun. 2010;15(suppl 2):197–210.

- , , , , , . Factors associated with unplanned hospital readmission among patients 65 years of age and older in a Medicare managed care plan. Am J Med. 1999;107(1):13–17.

- , , , et al. Gender as risk factor for 30 days post‐discharge hospital utilisation: a secondary data analysis. BMJ Open. 2012;2(2):e000428.

- , , , et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993;25(6):391–395.

- , , . The impact of patient socioeconomic status and other social factors on readmission: a prospective study in four Massachusetts hospitals. Inquiry. 1994;31(2):163–172.

- , , , . A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383.

- , , , . Continuity of care and patient outcomes after hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(6):624–631.

- , , , et al. Readmission after hospitalization for congestive heart failure among Medicare beneficiaries. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(1):99–104.

- , , . Minor depression: risk profiles, functional disability, health care use and risk of developing major depression. J Affect Disord. 2004;79(1‐3):71–79.

- , , , et al. Relationship of depression to increased risk of mortality and rehospitalization in patients with congestive heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(15):1849–1856.

- , , , et al. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient‐level meta‐analysis. JAMA. 2010;303(1):47–53.

- , , , et al. Depression is a risk factor for rehospitalization in medical inpatients. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9(4):256–262.

- , , , et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. BMJ. 2004;329(7456):15–19.

- , , , et al. The effect of adherence on the association between depressive symptoms and mortality among HIV‐infected individuals first initiating HAART. AIDS. 2007;21(9):1175–1183.

- , , , et al. Symptoms of depression prospectively predict poorer self‐care in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2008;25(9):1102–1107.

- , , . Self‐efficacy mediates the relationship between depressive symptoms and medication adherence among hypertensive African Americans. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36(1):127–137.

- , . The impact of depression on social skills. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192(4):260–268.

- , , , et al. Relationship between left ventricular dysfunction and depression following myocardial infarction: data from the MIND‐IT. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(24):2650–2656.

- , , , et al. Platelet/endothelial biomarkers in depressed patients treated with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor sertraline after acute coronary events: the Sertraline AntiDepressant Heart Attack Randomized Trial (SADHART) Platelet Substudy. Circulation. 2003;108(8):939–944.

- , , , , , . Psychological treatment of depression in inpatients: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(3):353–360.

Unplanned hospital readmission within 30 days is an important marker of the quality of care provided in the hospital and in the immediate posthospital setting.[1] In the United States, 1 in 5 Medicare patients is readmitted within 30 days, and related Medicare costs are estimated to be $17 billion annually.[2] Public policy is attempting to drive down healthcare costs in the United States via the Affordable Care Act by reducing payments to hospitals that have high 30‐day readmission rates.[3]

The prevalence of depression is 6.7% of adults,[4] and depressive symptomatology has been linked to hospital readmission.[5, 6] Depressive symptoms are associated with poor health outcomes and increased utilization. Patients with cardiac disease and depressive symptoms have worse outcomes.[7] Mild symptoms are associated with increased primary care and mental health care visits.[8] Both mild and moderate‐to‐severe depressive symptomatology are associated with symptom burden, physical limitation, quality of life, and overall health.[9] Importantly, many hospitalized patients, who do not have a diagnosis of depression, display depressive symptomatology.[10] A gap in knowledge exists as to the utility of stratifying depressive symptomatology between mild and moderate to severe in determining risk for hospital readmission.

Although the causal pathway to worse outcomes in patients with a diagnosis of depression has been studied,[11] the reasons for poor outcomes of patients with depressive symptomatology have not been well described, particularly in hospitalized general medical patients. Nonadherence to physician recommendations, decreased cognitive function, and poor adherence to self‐care recommendations[12, 13, 14] may explain increased healthcare utilization. Physiological models hypothesize heightened levels of proinflammatory markers[15, 16] and vascular depression[17] may play a role. There remains a gap in knowledge as to the postdischarge utilization of hospitalized patients with depressive symptomatology.

We studied the rate of hospital readmission among hospitalized adult patients with mild and moderate‐to‐severe depressive symptoms as defined by the 9‐Item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ‐9) depression screening tool.[18]

METHODS

Setting, Data, and Participants

Data from 2 Project Re‐Engineered Discharge (RED) clinical trials were included in a secondary analysis.[19, 20, 21] Depressive symptom screening data were available for 1418 participants originally randomized to the control and experimental groups in each trial.

The Project RED trials were a set of 2‐armed randomized controlled trials studying hospital utilization following a standardized hospital‐based discharge process. Inclusion criteria included English‐speaking patients who were 18 years or older and admitted to the adult medical service at Boston Medical Center, a large urban safety‐net hospital with an ethnically diverse patient population. Patients were required to have a telephone and have plans to return home after discharge. Patients were excluded if admitted from a skilled nursing facility or other hospital, transferred to a different hospital service before enrollment, admitted for a planned hospitalization, on hospital precautions, on suicide watch, or were deaf or blind. A full description of the methods has been described.[19] The second RED trial differed in that a health information technology system was used to teach the discharge plan to subjects at the time of discharge rather than a nurse.[20, 21]

The institutional review board of Boston University approved all study activities.

Outcome Variables

The primary end point for this analysis was the hospital readmission rate, defined as the total number of readmissions per subject within 30 days of the index discharge. Data were collected by hospital electronic medical record (EMR) review and by contacting subjects by telephone 30 days after discharge. Research staff collected data and were blinded to study group assignment. We examined emergency department (ED) utilization and primary care physician (PCP) follow‐up visit attendance rates within 30 days of discharge. Any ED or ambulatory visit resulting in hospital admission within 30 days of the index discharge date was counted as 1 readmission. Readmission and ED utilization dates occurring at Boston Medical Center were obtained from its EMR, whereas those at other hospitals were collected through subject report.

Primary Independent Variable

The primary independent variable was the PHQ‐9 screening questionnaire score, designed to identify patients with depressive symptoms. Data were collected at the time of enrollment during the index admission. Symptoms were categorized into 3 groups: no depression (PHQ‐9 score of 04, or less than a score of 2 on the first 2 questions of the PHQ‐9), mild depressive symptoms (PHQ‐9 score of 59), and moderate‐to‐severe symptoms (PHQ‐9 score of 1027).[18]

Statistical Analysis

Potential confounders were identified a priori from available literature on factors associated with hospital readmission. These included age,[22] race, gender,[23] marital status, health literacy (using the Rapid Estimate of Health Literacy in Adult Medicine [REALM] tool),[24] insurance type, employment status, income level,[25] Charlson Comorbidity Index,[26] homelessness within the past 3 months, hospital utilization within the 6 months before the index hospitalization,[27] educational attainment, length of hospital stay,[28] and study group assignment.

Demographic and other characteristics were compared by dichotomized healthcare reutilization outcomes using bivariate analysis to identify potential confounders of the relationship between depressive symptom severity and hospital readmission. [2] tests were used for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. Age (years) and length of stay (days) were used as continuous variables. Gender (male/female), frequent hospital admission within 6 months (01 vs 2 or more), homelessness, and presence of substance use disorder diagnosis (defined by the International Statistical Classification of Disease, 9th Revision [ICD‐9] diagnosis codes, which included 303.0 [alcohol dependence], 305.0 [alcohol abuse], 291.0 [alcohol‐induced mental disorders], 304.0 [drug dependence], 305.2305.7, 305.9 [drug abuse] and 292.0 [drug‐induced mental disorders]) were treated as dichotomous variables. Categorical variables were created for marital status (single, married, divorced/widowed), educational attainment (less than or incomplete high school, high school graduate, some college, college graduate), insurance type (Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, or Free Care), income level (<$19,999 per year, $20,00039,000, $40,00074,999, >$75,000, or unknown/refused to answer), employment status (working full time, working part time, not working, or no answer), and health literacy level according to REALM score (044 [grade 6 or below], 4560 [grade 78], or 6166 [grade 9 or above]).

The readmission rate reflects the number of hospital readmission events per subject within 30 days of discharge. The PCP follow‐up rate reflects the number of subjects attending a posthospital PCP visit within 30 days of discharge. The incidence rate ratio (IRR) was calculated to compare the rates of readmission between those with mild, moderate to severe, and no depressive symptoms. Readmission data at 30 days are cumulative. Poisson models were used to test for significant differences between the predicted and observed number of events at 30 days. A stepwise selection process (with =0.2 as entry and exit criteria) was conducted to identify relevant confounders and to construct the final model for the association between depressive symptom screen severity and readmission. Using sensitivity analysis, we tested a model including substance abuse as a variable. This did not substantially change our final model, and therefore we did not include this variable in the final model.

A Kaplan‐Meier hazard curve was generated for time from the index discharge to the first hospital readmission within 30 days. The hazard of readmission was compared among the 3 depressive symptom screen categories using Cox proportional hazards. Two‐sided significance tests were used. P values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All data were analyzed with SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Adjusted Poisson regression results identified individuals with readmission and/or ED utilization rates much higher than the sample mean. Data points with 5 or more hospital readmissions or 7 or more combined readmissions and ED utilizations were removed from analysis.

RESULTS

Of the total study population, 15.9% (225/1418) demonstrated mild depressive symptoms, and 23.7% (336/1418) demonstrated moderate‐to‐severe symptoms. Of those in our study, 38.9% (551/1418) self‐reported being told by a healthcare professional that they had depression. Of those self‐reporting depression, 27.9% (273/540) were currently taking antidepressant medication at the time of the index hospitalization. Table 1 shows baseline characteristics by dichotomized utilization outcome. Mean age, marital status, health insurance, employment status, mean length of stay, admissions in the previous 6 months, mean Charlson score, and substance abuse were significantly associated with hospital readmission. Of these characteristics, all but mean length of stay and previous history of substance abuse were significantly associated with ED utilization.

| Hospital Readmission | ED Utilization | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, n=1,240 | Yes, n=193 | No, n=1,231 | Yes, n=202 | |

| ||||

| Male, n (%) | 602 (48.6) | 105 (54.4) | 606 (49.3) | 101 (50.0) |

| Mean age, y (SD) | 49.14 (14.21)a | 52.24 (14.69)a | 50.06 (14.57)a | 46.45 (12.19)a |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White non‐Hispanic | 332 (26.8) | 73 (37.8) | 357 (29.0) | 48 (23.8) |

| Black non‐Hispanic | 666 (53.7) | 89 (46.1) | 646 (52.5) | 109 (54.0) |

| Hispanic | 135 (10.9) | 19 (9.8) | 124 (10.1) | 30 (14.9) |

| Other or mixed race | 59 (4.8) | 7 (3.6) | 56 (4.6) | 10 (5.0) |

| Unknown | 48 (3.9) | 5 (2.6) | 48 (3.9) | 5 (2.5) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||

| Single | 593 (47.8)a | 74 (38.3)a | 552 (44.8)a | 115 (56.9)a |

| Married | 286 (23.1)a | 42 (21.8)a | 296 (24.1)a | 32 (15.8)a |

| Divorced/widowed | 346 (27.9)a | 74 (38.3)a | 369 (20.0)a | 51 (25.3)a |

| Unknown | 15 (1.2)a | 3 (1.6)a | 14 (1.1)a | 4 (2.0)a |

| Annual personal income, n (%) | ||||

| <$19,999 | 511 (41.2) | 88 (45.6) | 509 (41.4) | 90 (44.6) |

| $20,000$39,999 | 184 (14.8) | 22 (11.4) | 175 (14.2) | 31 (15.4) |

| $40,000$74,999 | 107 (8.6) | 14 (7.3) | 111 (9.0) | 10 (5.0) |

| >$75,000 | 41 (3.3) | 8 (4.2) | 44 (3.6) | 5 (2.5) |

| Unknown/refused | 397 (32.0) | 61 (31.6) | 392 (31.8) | 66 (32.7) |

| Health insurance, n (%) | ||||

| Private | 321 (25.9)a | 34 (17.6)a | 316 (25.7)a | 39 (19.3)a |

| Medicaid | 510 (41.1)a | 90 (46.6)a | 485 (39.4)a | 115 (56.9)a |

| Medicare | 138 (11.1)a | 43 (22.3)a | 170 (13.8)a | 11 (5.5)a |

| Free Care | 207 (16.7)a | 14 (7.3)a | 190 (15.4)a | 31 (15.4)a |

| Other/unknown | 64 (5.2)a | 12 (6.2)a | 70 (5.7)a | 6 (3.0)a |

| Education level, n (%) | ||||

| Incomplete high school | 290 (23.4) | 45 (23.3) | 288 (23.4) | 47 (23.3) |

| High school graduate/GED | 492 (39.7) | 87 (45.1) | 489 (39.7) | 90 (44.6) |

| Some college | 257 (20.7) | 34 (17.6) | 255 (20.7) | 36 (17.8) |

| College degree | 183 (14.8) | 25 (13.0) | 183 (14.9) | 25 (12.4) |

| Unknown | 18 (1.5) | 2 (1.0) | 16 (1.3) | 4 (2.0) |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||||

| Full time | 322 (26.4)a | 31 (16.6)a | 316 (26.2)a | 37 (18.7)a |

| Part time | 136 (11.2)a | 11 (5.9)a | 124 (10.3)a | 23 (11.6)a |

| Retired | 172 (14.1)a | 37 (19.8)a | 196 (16.2)a | 13 (6.6)a |

| Disabled | 278 (22.8)a | 72 (38.5)a | 287 (23.8)a | 63 (31.8)a |

| Unemployed | 286 (23.5)a | 31 (16.6)a | 258 (21.4)a | 59 (29.8)a |

| Student | 24 (2.0)a | 5 (2.7)a | 26 (2.2)a | 3 (1.5)a |

| Homeless in past 6 months, n (%) | 143 (11.6) | 24 (12.5) | 126 (10.3) | 41 (20.4) |

| Health literacy, n (%)b | ||||

| 6th‐grade level | 230 (19.2) | 41 (22.4) | 228 (19.2) | 43 (22.4) |

| 7th8th‐grade level | 342 (28.5) | 60 (32.8) | 342 (28.7) | 60 (31.3) |

| 9th‐grade level | 627 (52.3) | 82 (44.8) | 620 (52.1) | 89 (46.4) |

| Mean length of stay, d (SD) | 2.69 (2.60)a | 3.57 (3.50)a | 2.81 (2.80) | 2.84 (2.18) |

| PCP at enrollment, n (%)c | 1,005 (81.1) | 166 (86.0) | 1,005 (81.7) | 166 (82.2) |

| 2 Admissions in past 6 months, n (%) | 300 (24.2)a | 81 (42.0)a | 292 (23.7)a | 89 (44.1)a |

| Mean Charlson score (SD)d | 2.19 (2.53)a | 2.85 (2.78)a | 2.34 (2.60)a | 1.92 (2.18)a |

| Substance abuse, n (%)e | 138 (12.0)a | 36 (19.7)a | 151 (13.1) | 23 (12.6) |

Table 2 shows the unadjusted 30 day hospital readmission, ED utilization, and PCP follow‐up rates. Participants with mild symptoms had higher readmission rates than those without symptoms (0.20 vs 0.13). In other words, 20 readmissions occurred per 100 subjects with mild symptoms, compared with 13 readmissions per 100 subjects without symptoms (P<0.001). The readmission rate was 0.21 for subjects with moderate‐to‐severe depression. The rate of ED utilization for subjects with mild symptoms was 0.18. This was significantly different from ED utilization rates of those with no depression and those with moderate‐to‐severe symptoms, which were 0.16 and 0.28, respectively (P<0.001). The postdischarge follow‐up rates were different for those without depression compared to those with mild and moderate‐to‐severe symptoms (58.7, 49.5, and 51.1, respectively), but this did not reach statistical significance (P=0.06).

| Depressive Symptom Severity Based on PHQ‐9 Score, N=1,418 | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Depression, n=857 | Mild Depressive Symptoms, n=225 | Moderate‐to‐Severe Depressive Symptoms, n=336 | ||

| ||||

| Hospital readmission, n (rate per 100) | 108 (12.6) | 44 (19.6) | 71 (21.1) | <0.001 |

| ED utilization, n (rate per 100) | 133 (15.5) | 41 (18.2) | 94 (28.0) | <0.001 |

| PCP follow‐up, n (rate per 100) | 420 (58.7) | 103 (49.5) | 157 (51.1) | 0.06 |

Poisson analyses were conducted to control for potential confounding in the relationship between symptom severity and readmission or ED utilization (Table 3). Compared to subjects with no depression, the association between mild symptoms and readmission remained significant (adjusted IRR: 1.49; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.11‐2.00) after controlling for relevant confounders. For those with moderate‐to‐severe symptoms, the adjusted IRR was 1.96 (95% CI: 1.51‐2.49). When compared to those without depression, the adjusted IRR for ED reutilization was not found to be significant for those with mild symptoms (1.30; 95% CI: 0.96‐1.76) and significant for those participants with moderate‐to‐severe symptoms (1.48; 95% CI: 1.16‐1.89).

| Depressive Symptom Severity Based on PHQ‐9 Score, N=1418 | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Depression, n=857 | Mild Depressive Symptoms, n=225 | Moderate‐to‐Severe Depressive Symptoms, n=336 | ||

| ||||

| Hospital readmission, n (rate per 100) | 96 (11.9) | 36 (17.1) | 67 (21.1) | <0.001 |

| Hospital readmission IRR (95% CI) | Ref | 1.49 (1.11‐2.00) | 1.96 (1.51‐2.49) | |

| ED utilization, n (rate per 100) | 124 (15.2) | 40 (19.0) | 85 (26.7) | 0.007 |

| ED utilization IRR (95% CI) | Ref | 1.30 (0.96‐1.76) | 1.48 (1.16‐1.89) | |

Figure 1 depicts the hazard curve generated for the time to first hospital readmission, stratified by depressive symptom severity. A readmission within 30 days following an index discharge date occurred in 10% of participants without depression, 14% of those with mild symptoms, and 19% of those with moderate‐to‐severe symptoms (P=0.03).

DISCUSSION

Our study shows hospitalized medical patients at an urban academic hospital with a positive screen for depressive symptoms are significantly more likely to be readmitted within 30 days of discharge as compared to those who do not screen positive. The significant association of depressive symptoms and readmission remains even after stratifying by severity and controlling for relevant confounders. Further, there appears to be a dose‐response relationship between depressive symptom severity and readmission. This graded effect makes the distinction between mild and moderate‐to‐severe depressive symptoms a better instrument at predicting rehospitalization than a diagnostic code for depression. Few studies have analyzed the readmission of general medical patients stratified by depressive symptomatology, and even fewer have addressed the presence of mild depressive symptomatology as it relates to readmission. A diagnosis of mild depression is associated with similar though less severe outcomes as compared to major depression, including negative effects on quality of life, functional disability, health status, and mortality.[29] Patients with heart failure and mild depressive symptoms have higher rates of readmission at 3 months and 1 year as compared with those without depressive symptoms, but these findings were not found to be significant.[30] Mild depressive symptoms may contribute to readmission, accrued medical cost, and burden of disease.

We extend previous research[5, 31, 32] by showing that, compared to those without and those with mild symptoms, the readmission risk is even greater for those who screen positive for moderate‐to‐severe symptoms. The mechanism linking depressive symptoms and readmission is not well understood. Behavioral mechanisms such as physical symptom amplification or anxiety about symptoms link depressive symptoms to healthcare utilization after discharge.[33] Depressive symptoms among patients with diabetes, asthma, hypertension, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) impairs medication adherence and self‐care behavior.[14, 34, 35, 36] Depressed patients might have reduced social support leading to increased stress, worsened symptoms, and prolonged recovery.[37] These mechanisms may prompt patients to present to hospitals for reevaluation. The direct physiologic consequences of depressive symptoms may be similar to that of the diagnosis of depression. Patients with cardiovascular disease and depression have poor outcomes, which may be related to decreased heart rate variability, hypercoagulability, high burden of inflammatory markers, and severity of left ventricular dysfunction.[38, 39] Among patients with HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and coronary artery disease, depression is linked to increased proinflammatory marker levels and less favorable outcomes, which may signal a more severe form of the disease or an impaired response to treatment.[15, 16]

Our data have several implications. Though disease burden may play a role in the presence of depressive symptomatology in hospitalized patients, screen‐positive patients still experienced more readmission events as compared to those without depressive symptoms after controlling for relevant confounders. Further, there appears to be a dose‐dependent relationship between depressive symptom severity and rate of readmission. Use of a categorical ICD‐9 code often implies that the diagnosis of depression has been confirmed. Rather than using administrative ICD‐9 codes to account for readmission risk, hospitals may consider screening patients for depressive symptoms during hospitalizations to both identify and risk‐stratify patients at high risk for readmission. Procedures should be implemented to address barriers to safe transitions in care in the screen‐positive population. The relationship between symptom severity and readmission rate may aid in the decision to devote resources to those at highest risk of readmission. Lastly, though research on the treatment of depressive symptoms in medical inpatients has been inconclusive in determining whether this approach is better than usual care or structured pharmacotherapies,[40] further study is needed to determine whether treatment of mild and moderate‐to‐severe depressive symptoms during an acute medical hospitalization will decrease readmission.

Strengths of the current study include the large dataset, the broad range of covariates available for analyses, and the inclusive nature of the sample, which was not restricted to factors such as age or medical condition.

Several limitations should be noted. We did not conduct a psychiatric evaluation to evaluate screen‐positive patients who met diagnostic criteria for minor or major depressive disorder, nor did we reconfirm the presence of symptoms at the time of or following hospital discharge. Our data, then, may not reflect patients' depressive symptomatology prior to the index hospitalization or at the time of discharge. Although such data might further refine the use of depressive symptomatology in identifying patients at high risk for readmission, our findings demonstrate that simply screening positive for depressive symptomatology at time of admission is associated with increased risk of readmission. We do not know the direction of the reported associations. If depressive symptoms are the consequence of higher disease burden, treatment of the underlying disease may be the most important intervention. Although this is possible, our model does include variables (eg, length of stay, Charlson Comorbidity Index), which are likely to adjust for disease severity, pointing to the likelihood that depressive symptoms truly predict hospital readmission independent of disease severity. Data on utilization outside Boston Medical Center (about 9% of outcomes) were determined by patient self‐report and not confirmed by document review. Our results may not be generalizable to populations other than those served by an urban safety‐net hospital or other populations excluded from analysis (eg, nonEnglish‐speaking patients, patients from nursing homes). Finally, social factors such as social support may residually confound the relationship between depressive symptom severity and readmission.

Our finding linking both mild and moderate‐to‐severe depressive symptoms to increased readmission when compared to those without depressive symptoms is significant for future policy. If future studies demonstrate that the initiation of treatment of patients who screen positive for depressive symptoms during an acute hospitalization leads to reduced readmission, policymakers should increase support for mental health screening and programming as an integral portion of general medical patient management.

In conclusion, screening positive for mild or moderate‐to‐severe depressive symptoms is associated with an increased rate of early hospital readmission as compared to those without depressive symptoms, even after controlling for relevant confounders. The rate and hazard of hospital readmission increase with symptom severity. This finding has important implications for future research for hospital screening programming and interventions for patients who screen positive for depressive symptoms.

Disclosures: This research was funded in part by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (NCT00252057) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NCT00217867). Dr. Cancino has been paid for consulting work for PracticeUpdate, a subsidiary of Elsevier. Dr. Culpepper has been paid for participation in advisory boards by AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly and Co., Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc., Forest Labs, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Jazz Pharmaceuticals plc, H. Lundbeck A/S, Merck & Co., Pfizer Inc., Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals Inc., Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc., and Takeda Pharmaceuticals Inc. He has received payment for educational presentations regarding hospital readmission without mention of any pharmaceutical or other products from Merck. Dr. Mitchell has received honoraria from Merck for lectures on health behavior counseling. Trial registration: NCT00252057, NCT00217867.

Unplanned hospital readmission within 30 days is an important marker of the quality of care provided in the hospital and in the immediate posthospital setting.[1] In the United States, 1 in 5 Medicare patients is readmitted within 30 days, and related Medicare costs are estimated to be $17 billion annually.[2] Public policy is attempting to drive down healthcare costs in the United States via the Affordable Care Act by reducing payments to hospitals that have high 30‐day readmission rates.[3]

The prevalence of depression is 6.7% of adults,[4] and depressive symptomatology has been linked to hospital readmission.[5, 6] Depressive symptoms are associated with poor health outcomes and increased utilization. Patients with cardiac disease and depressive symptoms have worse outcomes.[7] Mild symptoms are associated with increased primary care and mental health care visits.[8] Both mild and moderate‐to‐severe depressive symptomatology are associated with symptom burden, physical limitation, quality of life, and overall health.[9] Importantly, many hospitalized patients, who do not have a diagnosis of depression, display depressive symptomatology.[10] A gap in knowledge exists as to the utility of stratifying depressive symptomatology between mild and moderate to severe in determining risk for hospital readmission.

Although the causal pathway to worse outcomes in patients with a diagnosis of depression has been studied,[11] the reasons for poor outcomes of patients with depressive symptomatology have not been well described, particularly in hospitalized general medical patients. Nonadherence to physician recommendations, decreased cognitive function, and poor adherence to self‐care recommendations[12, 13, 14] may explain increased healthcare utilization. Physiological models hypothesize heightened levels of proinflammatory markers[15, 16] and vascular depression[17] may play a role. There remains a gap in knowledge as to the postdischarge utilization of hospitalized patients with depressive symptomatology.

We studied the rate of hospital readmission among hospitalized adult patients with mild and moderate‐to‐severe depressive symptoms as defined by the 9‐Item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ‐9) depression screening tool.[18]

METHODS

Setting, Data, and Participants

Data from 2 Project Re‐Engineered Discharge (RED) clinical trials were included in a secondary analysis.[19, 20, 21] Depressive symptom screening data were available for 1418 participants originally randomized to the control and experimental groups in each trial.

The Project RED trials were a set of 2‐armed randomized controlled trials studying hospital utilization following a standardized hospital‐based discharge process. Inclusion criteria included English‐speaking patients who were 18 years or older and admitted to the adult medical service at Boston Medical Center, a large urban safety‐net hospital with an ethnically diverse patient population. Patients were required to have a telephone and have plans to return home after discharge. Patients were excluded if admitted from a skilled nursing facility or other hospital, transferred to a different hospital service before enrollment, admitted for a planned hospitalization, on hospital precautions, on suicide watch, or were deaf or blind. A full description of the methods has been described.[19] The second RED trial differed in that a health information technology system was used to teach the discharge plan to subjects at the time of discharge rather than a nurse.[20, 21]

The institutional review board of Boston University approved all study activities.

Outcome Variables

The primary end point for this analysis was the hospital readmission rate, defined as the total number of readmissions per subject within 30 days of the index discharge. Data were collected by hospital electronic medical record (EMR) review and by contacting subjects by telephone 30 days after discharge. Research staff collected data and were blinded to study group assignment. We examined emergency department (ED) utilization and primary care physician (PCP) follow‐up visit attendance rates within 30 days of discharge. Any ED or ambulatory visit resulting in hospital admission within 30 days of the index discharge date was counted as 1 readmission. Readmission and ED utilization dates occurring at Boston Medical Center were obtained from its EMR, whereas those at other hospitals were collected through subject report.

Primary Independent Variable

The primary independent variable was the PHQ‐9 screening questionnaire score, designed to identify patients with depressive symptoms. Data were collected at the time of enrollment during the index admission. Symptoms were categorized into 3 groups: no depression (PHQ‐9 score of 04, or less than a score of 2 on the first 2 questions of the PHQ‐9), mild depressive symptoms (PHQ‐9 score of 59), and moderate‐to‐severe symptoms (PHQ‐9 score of 1027).[18]

Statistical Analysis

Potential confounders were identified a priori from available literature on factors associated with hospital readmission. These included age,[22] race, gender,[23] marital status, health literacy (using the Rapid Estimate of Health Literacy in Adult Medicine [REALM] tool),[24] insurance type, employment status, income level,[25] Charlson Comorbidity Index,[26] homelessness within the past 3 months, hospital utilization within the 6 months before the index hospitalization,[27] educational attainment, length of hospital stay,[28] and study group assignment.

Demographic and other characteristics were compared by dichotomized healthcare reutilization outcomes using bivariate analysis to identify potential confounders of the relationship between depressive symptom severity and hospital readmission. [2] tests were used for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. Age (years) and length of stay (days) were used as continuous variables. Gender (male/female), frequent hospital admission within 6 months (01 vs 2 or more), homelessness, and presence of substance use disorder diagnosis (defined by the International Statistical Classification of Disease, 9th Revision [ICD‐9] diagnosis codes, which included 303.0 [alcohol dependence], 305.0 [alcohol abuse], 291.0 [alcohol‐induced mental disorders], 304.0 [drug dependence], 305.2305.7, 305.9 [drug abuse] and 292.0 [drug‐induced mental disorders]) were treated as dichotomous variables. Categorical variables were created for marital status (single, married, divorced/widowed), educational attainment (less than or incomplete high school, high school graduate, some college, college graduate), insurance type (Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, or Free Care), income level (<$19,999 per year, $20,00039,000, $40,00074,999, >$75,000, or unknown/refused to answer), employment status (working full time, working part time, not working, or no answer), and health literacy level according to REALM score (044 [grade 6 or below], 4560 [grade 78], or 6166 [grade 9 or above]).

The readmission rate reflects the number of hospital readmission events per subject within 30 days of discharge. The PCP follow‐up rate reflects the number of subjects attending a posthospital PCP visit within 30 days of discharge. The incidence rate ratio (IRR) was calculated to compare the rates of readmission between those with mild, moderate to severe, and no depressive symptoms. Readmission data at 30 days are cumulative. Poisson models were used to test for significant differences between the predicted and observed number of events at 30 days. A stepwise selection process (with =0.2 as entry and exit criteria) was conducted to identify relevant confounders and to construct the final model for the association between depressive symptom screen severity and readmission. Using sensitivity analysis, we tested a model including substance abuse as a variable. This did not substantially change our final model, and therefore we did not include this variable in the final model.

A Kaplan‐Meier hazard curve was generated for time from the index discharge to the first hospital readmission within 30 days. The hazard of readmission was compared among the 3 depressive symptom screen categories using Cox proportional hazards. Two‐sided significance tests were used. P values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All data were analyzed with SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Adjusted Poisson regression results identified individuals with readmission and/or ED utilization rates much higher than the sample mean. Data points with 5 or more hospital readmissions or 7 or more combined readmissions and ED utilizations were removed from analysis.

RESULTS

Of the total study population, 15.9% (225/1418) demonstrated mild depressive symptoms, and 23.7% (336/1418) demonstrated moderate‐to‐severe symptoms. Of those in our study, 38.9% (551/1418) self‐reported being told by a healthcare professional that they had depression. Of those self‐reporting depression, 27.9% (273/540) were currently taking antidepressant medication at the time of the index hospitalization. Table 1 shows baseline characteristics by dichotomized utilization outcome. Mean age, marital status, health insurance, employment status, mean length of stay, admissions in the previous 6 months, mean Charlson score, and substance abuse were significantly associated with hospital readmission. Of these characteristics, all but mean length of stay and previous history of substance abuse were significantly associated with ED utilization.

| Hospital Readmission | ED Utilization | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, n=1,240 | Yes, n=193 | No, n=1,231 | Yes, n=202 | |

| ||||

| Male, n (%) | 602 (48.6) | 105 (54.4) | 606 (49.3) | 101 (50.0) |

| Mean age, y (SD) | 49.14 (14.21)a | 52.24 (14.69)a | 50.06 (14.57)a | 46.45 (12.19)a |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White non‐Hispanic | 332 (26.8) | 73 (37.8) | 357 (29.0) | 48 (23.8) |

| Black non‐Hispanic | 666 (53.7) | 89 (46.1) | 646 (52.5) | 109 (54.0) |

| Hispanic | 135 (10.9) | 19 (9.8) | 124 (10.1) | 30 (14.9) |

| Other or mixed race | 59 (4.8) | 7 (3.6) | 56 (4.6) | 10 (5.0) |

| Unknown | 48 (3.9) | 5 (2.6) | 48 (3.9) | 5 (2.5) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||

| Single | 593 (47.8)a | 74 (38.3)a | 552 (44.8)a | 115 (56.9)a |

| Married | 286 (23.1)a | 42 (21.8)a | 296 (24.1)a | 32 (15.8)a |

| Divorced/widowed | 346 (27.9)a | 74 (38.3)a | 369 (20.0)a | 51 (25.3)a |

| Unknown | 15 (1.2)a | 3 (1.6)a | 14 (1.1)a | 4 (2.0)a |

| Annual personal income, n (%) | ||||

| <$19,999 | 511 (41.2) | 88 (45.6) | 509 (41.4) | 90 (44.6) |

| $20,000$39,999 | 184 (14.8) | 22 (11.4) | 175 (14.2) | 31 (15.4) |

| $40,000$74,999 | 107 (8.6) | 14 (7.3) | 111 (9.0) | 10 (5.0) |

| >$75,000 | 41 (3.3) | 8 (4.2) | 44 (3.6) | 5 (2.5) |

| Unknown/refused | 397 (32.0) | 61 (31.6) | 392 (31.8) | 66 (32.7) |

| Health insurance, n (%) | ||||

| Private | 321 (25.9)a | 34 (17.6)a | 316 (25.7)a | 39 (19.3)a |

| Medicaid | 510 (41.1)a | 90 (46.6)a | 485 (39.4)a | 115 (56.9)a |

| Medicare | 138 (11.1)a | 43 (22.3)a | 170 (13.8)a | 11 (5.5)a |

| Free Care | 207 (16.7)a | 14 (7.3)a | 190 (15.4)a | 31 (15.4)a |

| Other/unknown | 64 (5.2)a | 12 (6.2)a | 70 (5.7)a | 6 (3.0)a |

| Education level, n (%) | ||||

| Incomplete high school | 290 (23.4) | 45 (23.3) | 288 (23.4) | 47 (23.3) |

| High school graduate/GED | 492 (39.7) | 87 (45.1) | 489 (39.7) | 90 (44.6) |

| Some college | 257 (20.7) | 34 (17.6) | 255 (20.7) | 36 (17.8) |

| College degree | 183 (14.8) | 25 (13.0) | 183 (14.9) | 25 (12.4) |

| Unknown | 18 (1.5) | 2 (1.0) | 16 (1.3) | 4 (2.0) |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||||

| Full time | 322 (26.4)a | 31 (16.6)a | 316 (26.2)a | 37 (18.7)a |

| Part time | 136 (11.2)a | 11 (5.9)a | 124 (10.3)a | 23 (11.6)a |

| Retired | 172 (14.1)a | 37 (19.8)a | 196 (16.2)a | 13 (6.6)a |

| Disabled | 278 (22.8)a | 72 (38.5)a | 287 (23.8)a | 63 (31.8)a |

| Unemployed | 286 (23.5)a | 31 (16.6)a | 258 (21.4)a | 59 (29.8)a |

| Student | 24 (2.0)a | 5 (2.7)a | 26 (2.2)a | 3 (1.5)a |

| Homeless in past 6 months, n (%) | 143 (11.6) | 24 (12.5) | 126 (10.3) | 41 (20.4) |

| Health literacy, n (%)b | ||||

| 6th‐grade level | 230 (19.2) | 41 (22.4) | 228 (19.2) | 43 (22.4) |

| 7th8th‐grade level | 342 (28.5) | 60 (32.8) | 342 (28.7) | 60 (31.3) |

| 9th‐grade level | 627 (52.3) | 82 (44.8) | 620 (52.1) | 89 (46.4) |

| Mean length of stay, d (SD) | 2.69 (2.60)a | 3.57 (3.50)a | 2.81 (2.80) | 2.84 (2.18) |

| PCP at enrollment, n (%)c | 1,005 (81.1) | 166 (86.0) | 1,005 (81.7) | 166 (82.2) |

| 2 Admissions in past 6 months, n (%) | 300 (24.2)a | 81 (42.0)a | 292 (23.7)a | 89 (44.1)a |

| Mean Charlson score (SD)d | 2.19 (2.53)a | 2.85 (2.78)a | 2.34 (2.60)a | 1.92 (2.18)a |

| Substance abuse, n (%)e | 138 (12.0)a | 36 (19.7)a | 151 (13.1) | 23 (12.6) |

Table 2 shows the unadjusted 30 day hospital readmission, ED utilization, and PCP follow‐up rates. Participants with mild symptoms had higher readmission rates than those without symptoms (0.20 vs 0.13). In other words, 20 readmissions occurred per 100 subjects with mild symptoms, compared with 13 readmissions per 100 subjects without symptoms (P<0.001). The readmission rate was 0.21 for subjects with moderate‐to‐severe depression. The rate of ED utilization for subjects with mild symptoms was 0.18. This was significantly different from ED utilization rates of those with no depression and those with moderate‐to‐severe symptoms, which were 0.16 and 0.28, respectively (P<0.001). The postdischarge follow‐up rates were different for those without depression compared to those with mild and moderate‐to‐severe symptoms (58.7, 49.5, and 51.1, respectively), but this did not reach statistical significance (P=0.06).

| Depressive Symptom Severity Based on PHQ‐9 Score, N=1,418 | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Depression, n=857 | Mild Depressive Symptoms, n=225 | Moderate‐to‐Severe Depressive Symptoms, n=336 | ||

| ||||

| Hospital readmission, n (rate per 100) | 108 (12.6) | 44 (19.6) | 71 (21.1) | <0.001 |

| ED utilization, n (rate per 100) | 133 (15.5) | 41 (18.2) | 94 (28.0) | <0.001 |

| PCP follow‐up, n (rate per 100) | 420 (58.7) | 103 (49.5) | 157 (51.1) | 0.06 |

Poisson analyses were conducted to control for potential confounding in the relationship between symptom severity and readmission or ED utilization (Table 3). Compared to subjects with no depression, the association between mild symptoms and readmission remained significant (adjusted IRR: 1.49; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.11‐2.00) after controlling for relevant confounders. For those with moderate‐to‐severe symptoms, the adjusted IRR was 1.96 (95% CI: 1.51‐2.49). When compared to those without depression, the adjusted IRR for ED reutilization was not found to be significant for those with mild symptoms (1.30; 95% CI: 0.96‐1.76) and significant for those participants with moderate‐to‐severe symptoms (1.48; 95% CI: 1.16‐1.89).

| Depressive Symptom Severity Based on PHQ‐9 Score, N=1418 | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Depression, n=857 | Mild Depressive Symptoms, n=225 | Moderate‐to‐Severe Depressive Symptoms, n=336 | ||

| ||||

| Hospital readmission, n (rate per 100) | 96 (11.9) | 36 (17.1) | 67 (21.1) | <0.001 |

| Hospital readmission IRR (95% CI) | Ref | 1.49 (1.11‐2.00) | 1.96 (1.51‐2.49) | |

| ED utilization, n (rate per 100) | 124 (15.2) | 40 (19.0) | 85 (26.7) | 0.007 |

| ED utilization IRR (95% CI) | Ref | 1.30 (0.96‐1.76) | 1.48 (1.16‐1.89) | |

Figure 1 depicts the hazard curve generated for the time to first hospital readmission, stratified by depressive symptom severity. A readmission within 30 days following an index discharge date occurred in 10% of participants without depression, 14% of those with mild symptoms, and 19% of those with moderate‐to‐severe symptoms (P=0.03).

DISCUSSION

Our study shows hospitalized medical patients at an urban academic hospital with a positive screen for depressive symptoms are significantly more likely to be readmitted within 30 days of discharge as compared to those who do not screen positive. The significant association of depressive symptoms and readmission remains even after stratifying by severity and controlling for relevant confounders. Further, there appears to be a dose‐response relationship between depressive symptom severity and readmission. This graded effect makes the distinction between mild and moderate‐to‐severe depressive symptoms a better instrument at predicting rehospitalization than a diagnostic code for depression. Few studies have analyzed the readmission of general medical patients stratified by depressive symptomatology, and even fewer have addressed the presence of mild depressive symptomatology as it relates to readmission. A diagnosis of mild depression is associated with similar though less severe outcomes as compared to major depression, including negative effects on quality of life, functional disability, health status, and mortality.[29] Patients with heart failure and mild depressive symptoms have higher rates of readmission at 3 months and 1 year as compared with those without depressive symptoms, but these findings were not found to be significant.[30] Mild depressive symptoms may contribute to readmission, accrued medical cost, and burden of disease.

We extend previous research[5, 31, 32] by showing that, compared to those without and those with mild symptoms, the readmission risk is even greater for those who screen positive for moderate‐to‐severe symptoms. The mechanism linking depressive symptoms and readmission is not well understood. Behavioral mechanisms such as physical symptom amplification or anxiety about symptoms link depressive symptoms to healthcare utilization after discharge.[33] Depressive symptoms among patients with diabetes, asthma, hypertension, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) impairs medication adherence and self‐care behavior.[14, 34, 35, 36] Depressed patients might have reduced social support leading to increased stress, worsened symptoms, and prolonged recovery.[37] These mechanisms may prompt patients to present to hospitals for reevaluation. The direct physiologic consequences of depressive symptoms may be similar to that of the diagnosis of depression. Patients with cardiovascular disease and depression have poor outcomes, which may be related to decreased heart rate variability, hypercoagulability, high burden of inflammatory markers, and severity of left ventricular dysfunction.[38, 39] Among patients with HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and coronary artery disease, depression is linked to increased proinflammatory marker levels and less favorable outcomes, which may signal a more severe form of the disease or an impaired response to treatment.[15, 16]

Our data have several implications. Though disease burden may play a role in the presence of depressive symptomatology in hospitalized patients, screen‐positive patients still experienced more readmission events as compared to those without depressive symptoms after controlling for relevant confounders. Further, there appears to be a dose‐dependent relationship between depressive symptom severity and rate of readmission. Use of a categorical ICD‐9 code often implies that the diagnosis of depression has been confirmed. Rather than using administrative ICD‐9 codes to account for readmission risk, hospitals may consider screening patients for depressive symptoms during hospitalizations to both identify and risk‐stratify patients at high risk for readmission. Procedures should be implemented to address barriers to safe transitions in care in the screen‐positive population. The relationship between symptom severity and readmission rate may aid in the decision to devote resources to those at highest risk of readmission. Lastly, though research on the treatment of depressive symptoms in medical inpatients has been inconclusive in determining whether this approach is better than usual care or structured pharmacotherapies,[40] further study is needed to determine whether treatment of mild and moderate‐to‐severe depressive symptoms during an acute medical hospitalization will decrease readmission.

Strengths of the current study include the large dataset, the broad range of covariates available for analyses, and the inclusive nature of the sample, which was not restricted to factors such as age or medical condition.

Several limitations should be noted. We did not conduct a psychiatric evaluation to evaluate screen‐positive patients who met diagnostic criteria for minor or major depressive disorder, nor did we reconfirm the presence of symptoms at the time of or following hospital discharge. Our data, then, may not reflect patients' depressive symptomatology prior to the index hospitalization or at the time of discharge. Although such data might further refine the use of depressive symptomatology in identifying patients at high risk for readmission, our findings demonstrate that simply screening positive for depressive symptomatology at time of admission is associated with increased risk of readmission. We do not know the direction of the reported associations. If depressive symptoms are the consequence of higher disease burden, treatment of the underlying disease may be the most important intervention. Although this is possible, our model does include variables (eg, length of stay, Charlson Comorbidity Index), which are likely to adjust for disease severity, pointing to the likelihood that depressive symptoms truly predict hospital readmission independent of disease severity. Data on utilization outside Boston Medical Center (about 9% of outcomes) were determined by patient self‐report and not confirmed by document review. Our results may not be generalizable to populations other than those served by an urban safety‐net hospital or other populations excluded from analysis (eg, nonEnglish‐speaking patients, patients from nursing homes). Finally, social factors such as social support may residually confound the relationship between depressive symptom severity and readmission.

Our finding linking both mild and moderate‐to‐severe depressive symptoms to increased readmission when compared to those without depressive symptoms is significant for future policy. If future studies demonstrate that the initiation of treatment of patients who screen positive for depressive symptoms during an acute hospitalization leads to reduced readmission, policymakers should increase support for mental health screening and programming as an integral portion of general medical patient management.

In conclusion, screening positive for mild or moderate‐to‐severe depressive symptoms is associated with an increased rate of early hospital readmission as compared to those without depressive symptoms, even after controlling for relevant confounders. The rate and hazard of hospital readmission increase with symptom severity. This finding has important implications for future research for hospital screening programming and interventions for patients who screen positive for depressive symptoms.