User login

Pharmacologic management of autism spectrum disorder: A review of 7 studies

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction, including deficits in social reciprocity, nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction, and skills in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships.1 In addition, the diagnosis of ASD requires the presence of restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities.

Initially, ASD was considered a rare condition. In recent years, the reported prevalence has increased substantially. The most recent estimated prevalence is 1 in 68 children at age 8, with a male-to-female ratio of 4 to 1.2

Behavioral interventions are considered to be the most effective treatment for the core symptoms of ASD. Pharmacologic interventions are used primarily to treat associated or comorbid symptoms rather than the core symptoms. Aggression, self-injurious behavior, and irritability are common targets of pharmacotherapy in patients with ASD. Studies have provided support for the use of antipsychotic agents to treat irritability and associated aggressive behaviors in patients with autism,3 but because these agents have significant adverse effects—including extrapyramidal side effects, somnolence, and weight gain—their use requires a careful risk/benefit assessment. Stimulants have also been shown to be effective in treating comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity symptoms. The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to manage repetitive behaviors and anxiety is also common.

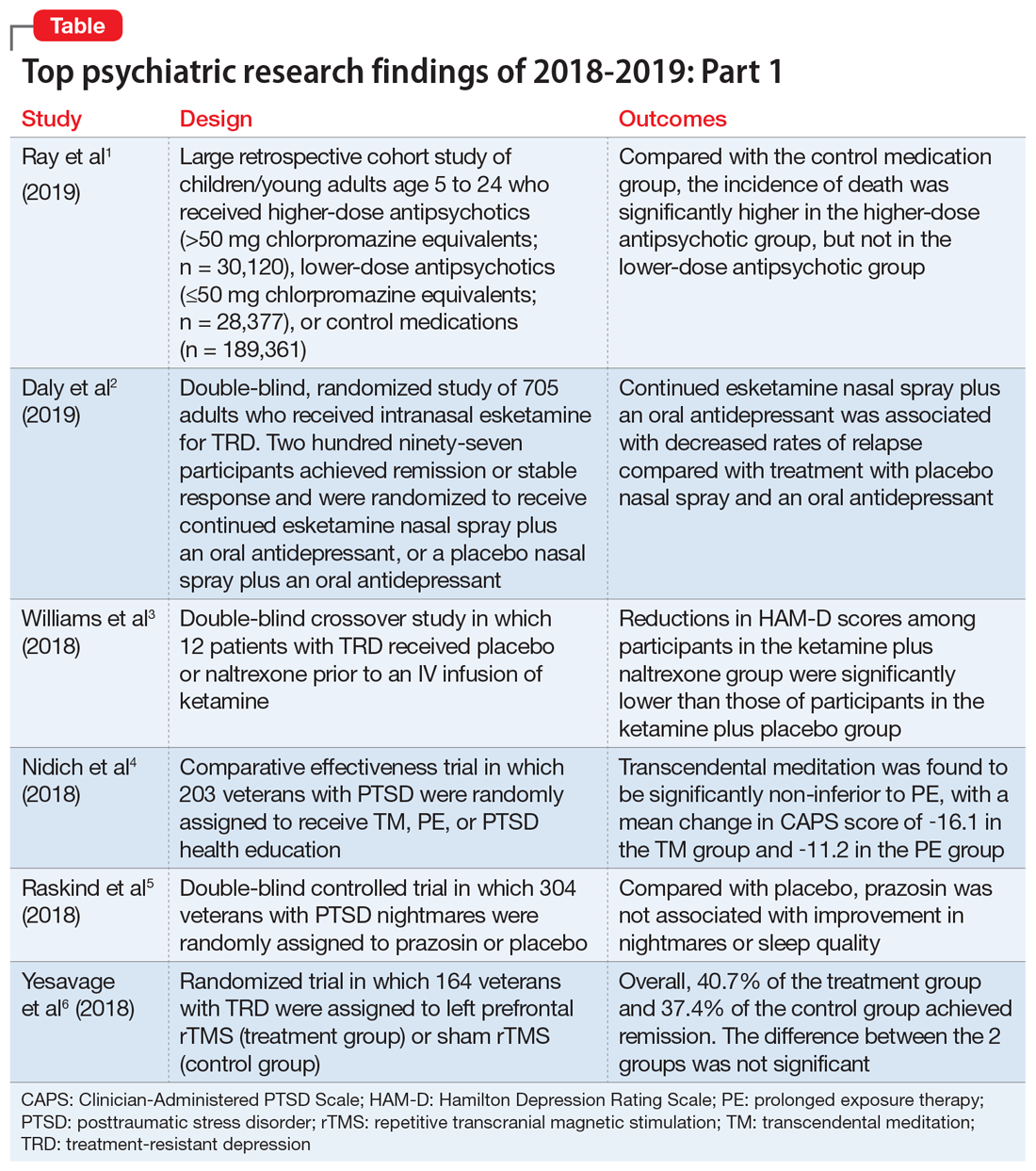

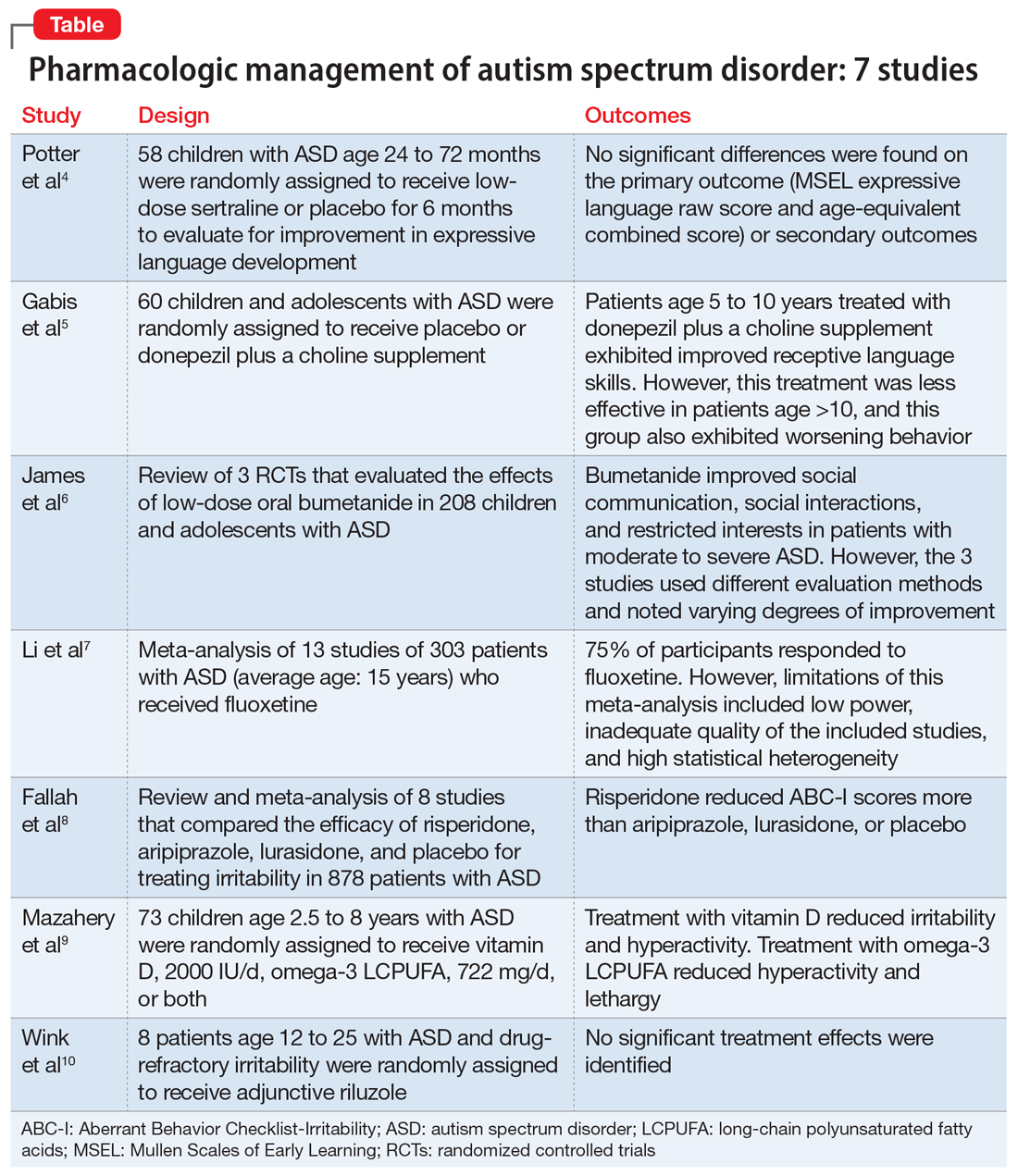

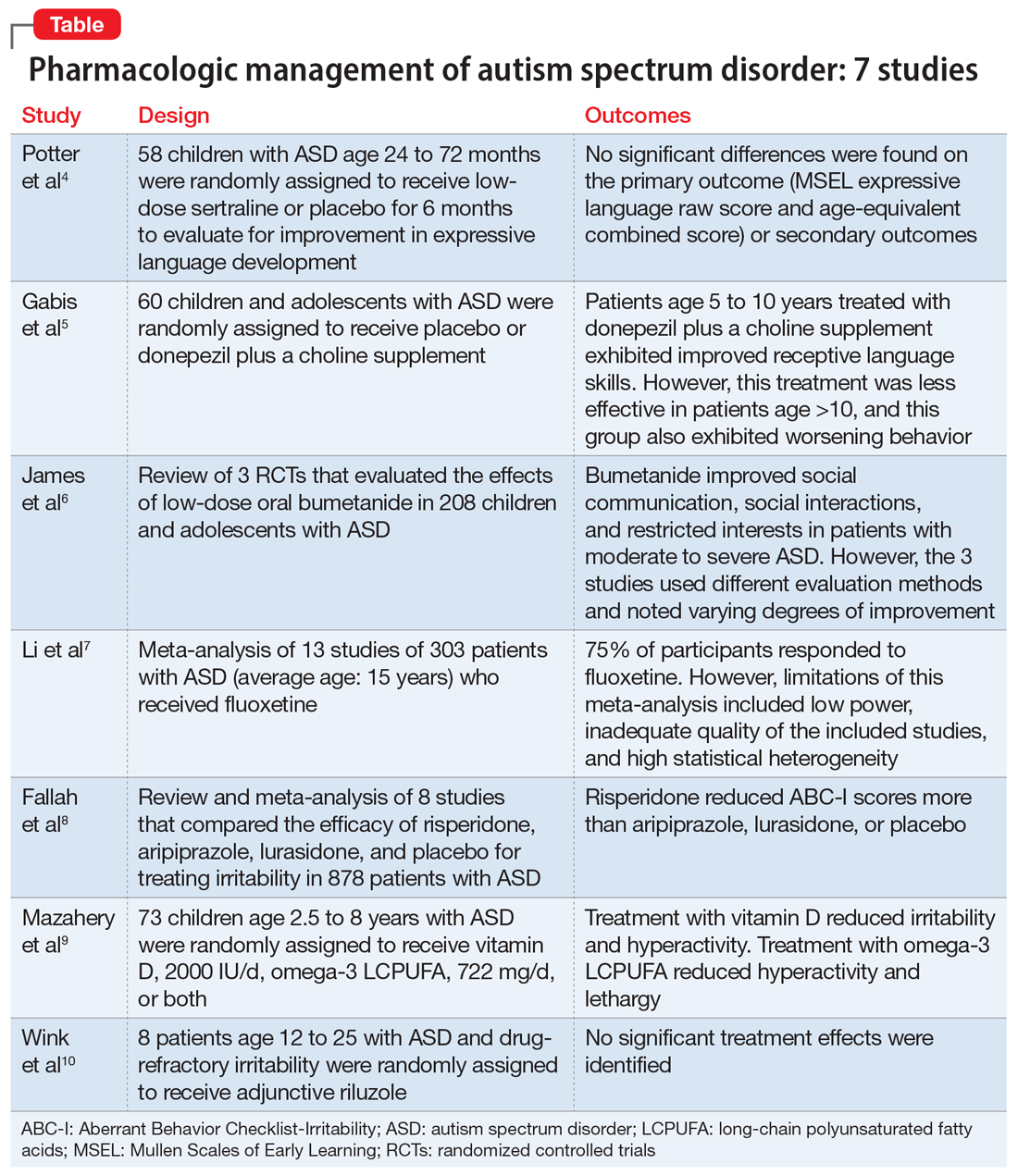

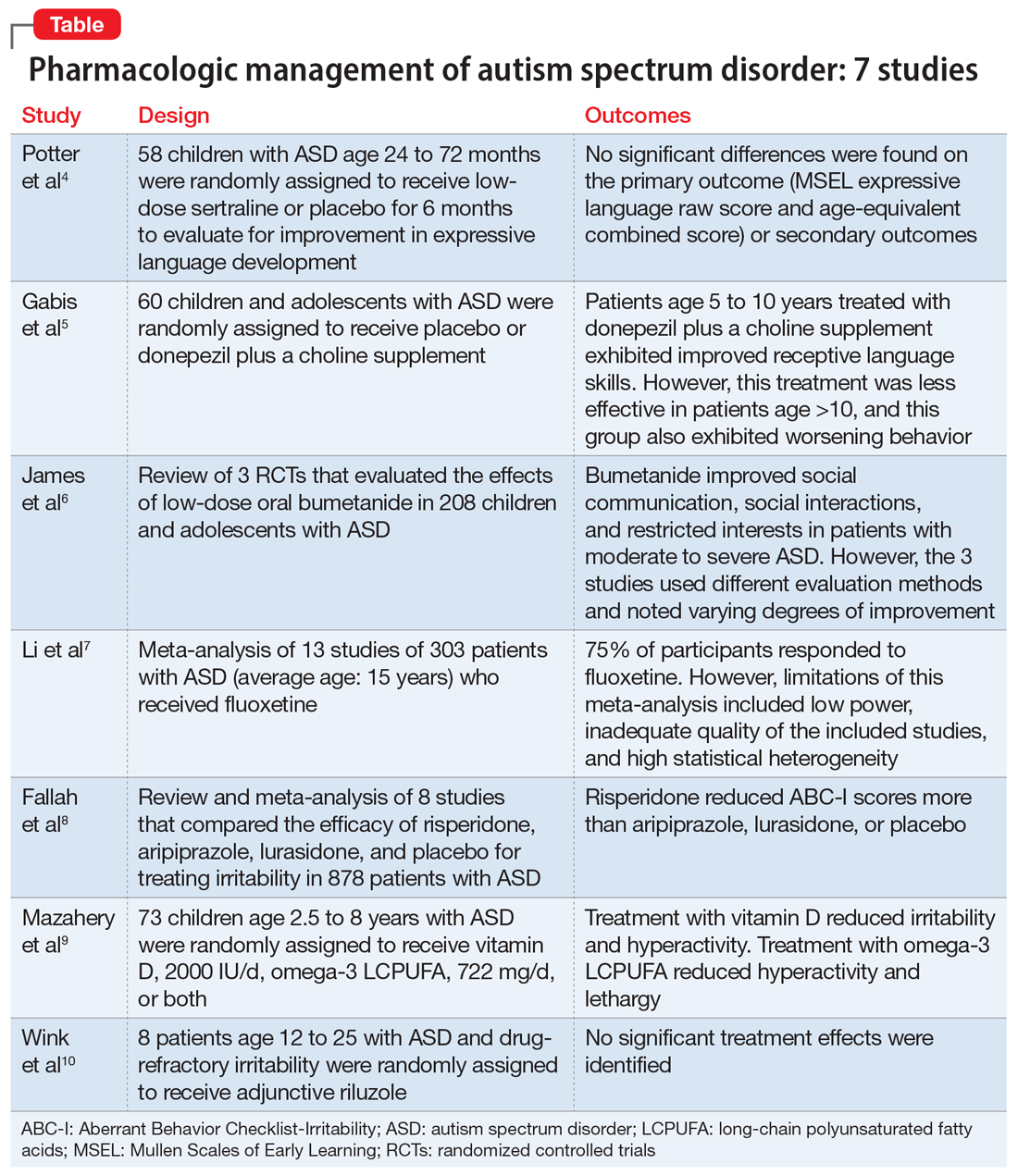

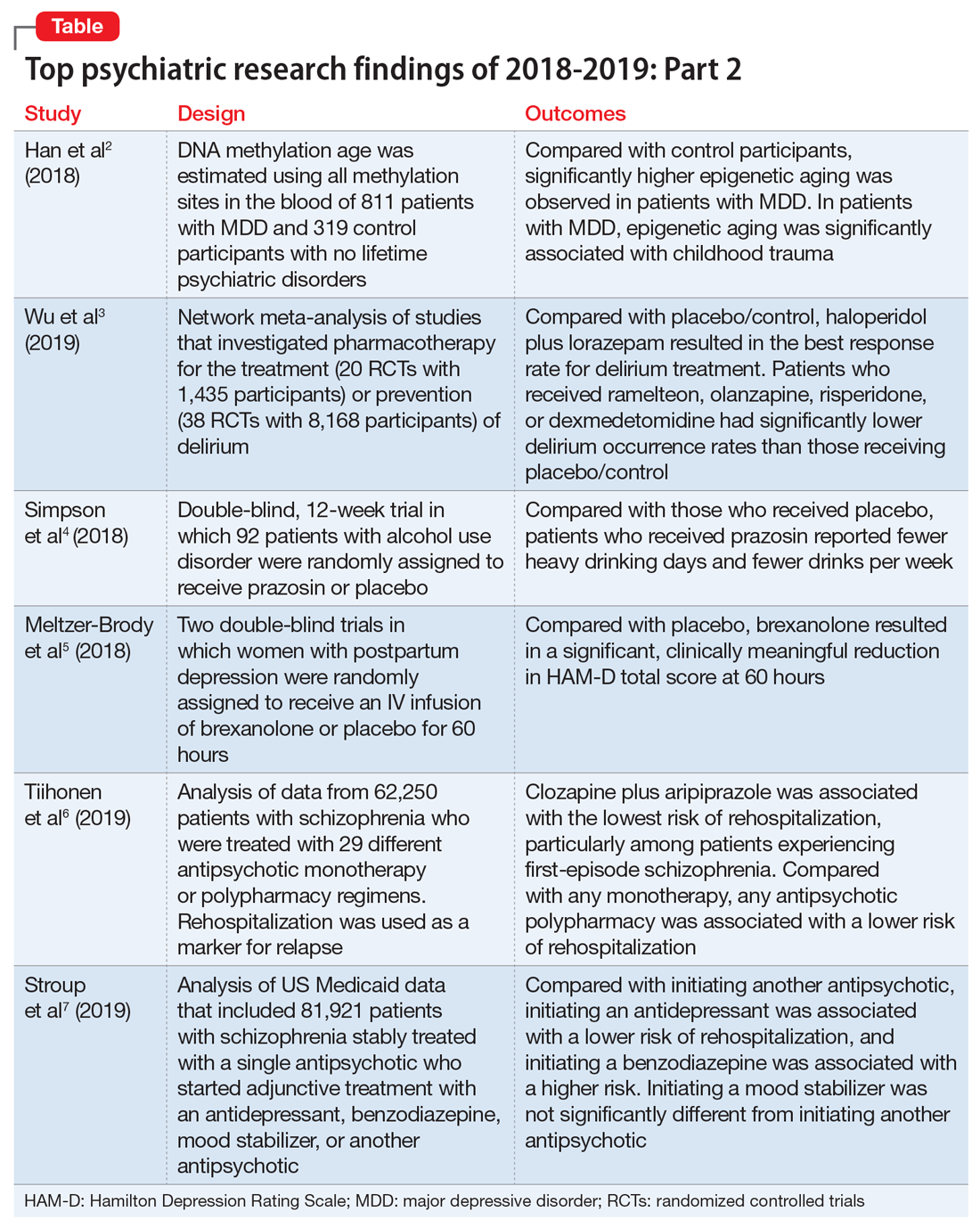

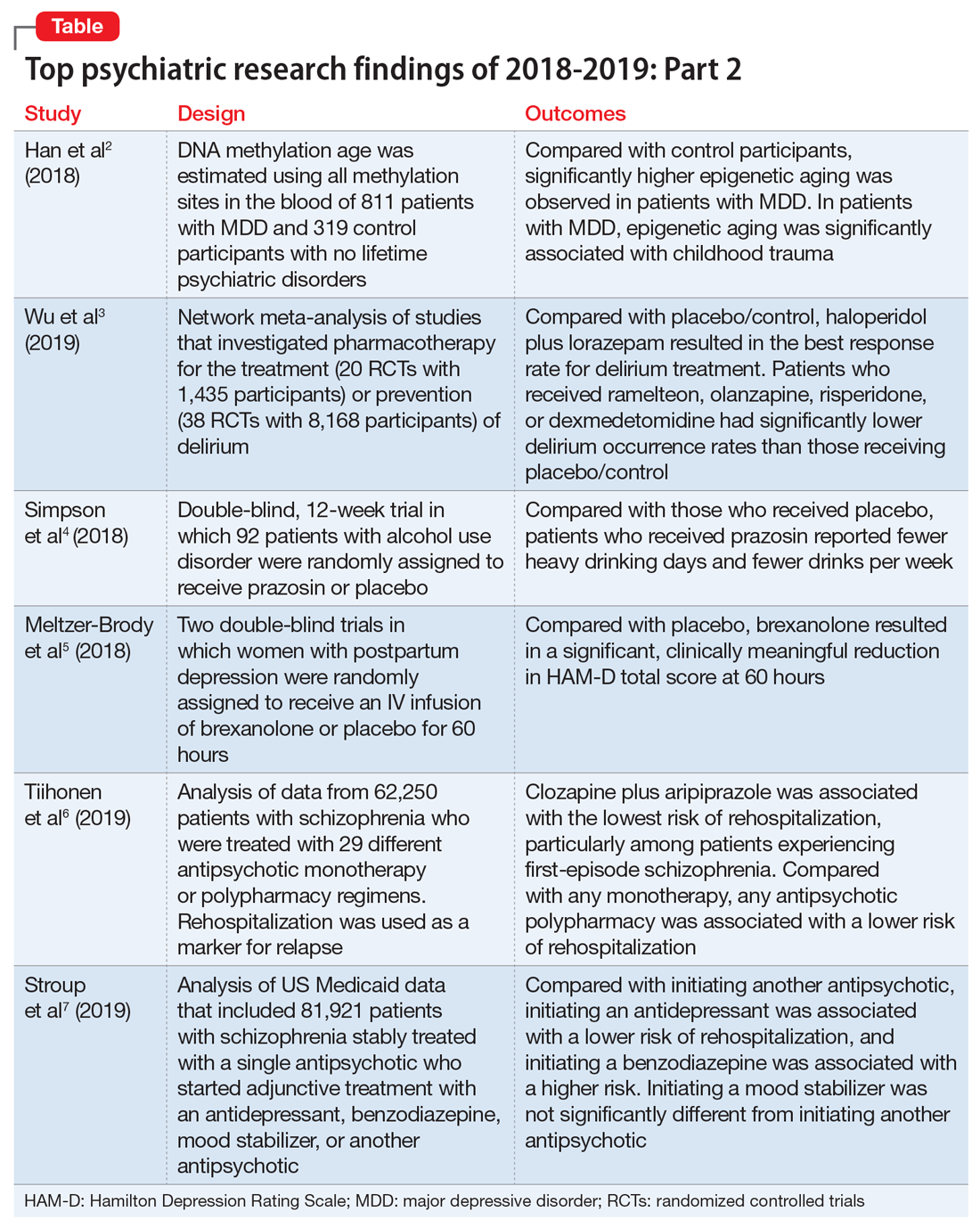

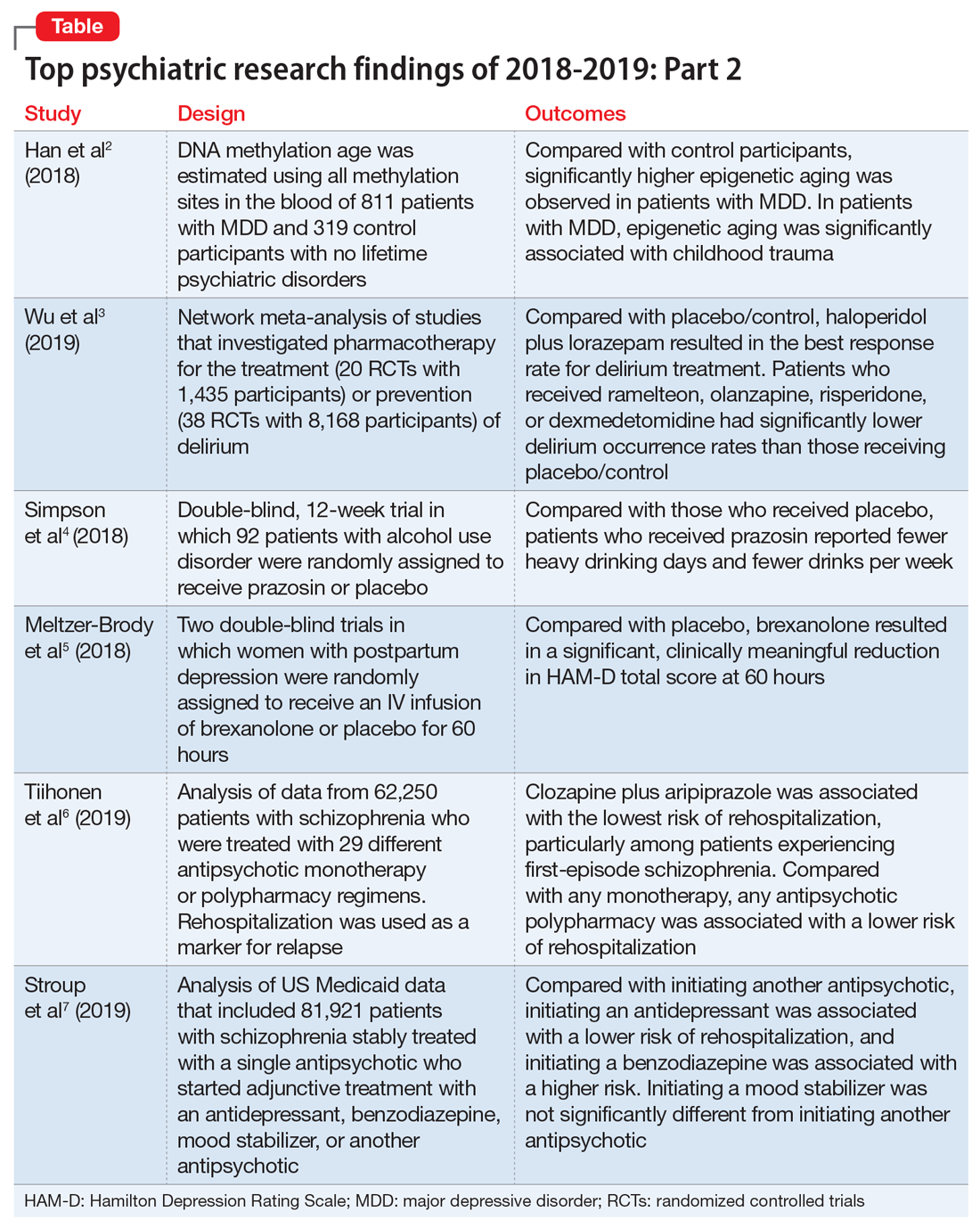

Here, we review 7 recent studies of the pharmacologic management of ASD (Table).4-10 These studies examined the role of SSRIs (sertraline, fluoxetine), an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor (donepezil), atypical antipsychotics (risperidone, aripiprazole, lurasidone), natural supplements (vitamin D, omega-3), a diuretic (bumetanide), and a glutamatergic modulator (riluzole) in the treatment of ASD symptoms.

1. Potter LA, Scholze DA, Biag HMB, et al. A randomized controlled trial of sertraline in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:810.

Several studies have shown that SSRIs improve language development in children with Fragile X syndrome, based on the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL). A previously published trial involving children with Fragile X syndrome and comorbid ASD found that sertraline improved expressive language development. Potter et al4 examined the role of sertraline in children with ASD only.

Study Design

- In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 58 children age 24 to 72 months with ASD received low-dose sertraline or placebo for 6 months.

- Of the 179 participants who were screened for eligibility, 58 were included in the study. Of these 58 participants, 32 received sertraline and 26 received placebo. The numbers of participants who discontinued from the sertraline and placebo arms were 8 and 5, respectively.

- Among those in the sertraline group, participants age <48 months received 2.5 mg/d, and those age ≥48 months received 5 mg/d.

Outcomes

- No significant differences were found on the primary outcome (MSEL expressive language raw score and age-equivalent combined score) or secondary outcomes (including Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement [CGI-I] scale at 3 months and end of treatment), as per intent-to-treat analyses.

- Sertraline was well tolerated. There was no difference in adverse effects between treatment groups and no serious adverse events.

Conclusion

- Although potentially useful for language development in patients with Fragile X syndrome with comorbid ASD, SSRIs such as sertraline have not proven efficacious for improving expressive language in patients with non-syndromic ASD.

- While 6-month treatment with low-dose sertraline in young children with ASD appears safe, the long-term effects are unknown.

Continue to: Gabis et al5 examined the safety...

2. Gabis LV, Ben-Hur R, Shefer S, et al. Improvement of language in children with autism with combined donepezil and choline treatment. J Mol Neurosci. 2019;69(2):224-234.

Gabis et al5 examined the safety and efficacy of utilizing donepezil, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, plus a choline supplement to treat both core features and associated symptoms in children and adolescents with ASD.

Study design

- This 9-month randomized, double-blind trial included 60 children/adolescents with ASD who were randomly assigned to receive placebo or donepezil plus a choline supplement. Participants underwent a baseline evaluation (E1), 12 weeks of treatment and re-evaluation (E2), 6 months of washout, and a final evaluation (E3).

- The baseline and final evaluations assessed changes in language performance, adaptive functioning, sleep habits, autism severity, clinical impression, and intellectual abilities. The evaluation after 12 weeks of treatment (E2) included all of these measures except intellectual abilities.

Outcomes

- Patients treated with donepezil plus a choline supplement had significant improvement in receptive language skills between E1 and E3 (P = .003).

- Patients treated with donepezil plus a choline supplement had significant worsening in scores on the Autism Treatment Evaluation Checklist (ATEC) health/physical behavior subscale between E1 and E2 (P = .012) and between E1 and E3 (P = .021).

- Improvement in receptive language skills was significant only in patients age 5 to 10 years (P = .047), whereas worsening in ATEC health/physical behavior subscale score was significant only in patients age 10 to 16 years (P = .024).

- Patients treated with donepezil plus a choline supplement reported higher percentages of gastrointestinal disturbance when compared with placebo (P = .007), and patients in the adolescent subgroup had a significant increase in irritability (P = .035).

Conclusion

- Patients age 5 to 10 years treated with donepezil plus a choline supplement exhibited improved receptive language skills. This treatment was less effective in patients age >10 years, and this group also exhibited behavioral worsening.

- Gastrointestinal disturbances were the main adverse effect of treatment with donepezil plus a choline supplement.

Continue to: The persistence of excitatory...

3. James BJ, Gales MA, Gales BJ. Bumetanide for autism spectrum disorder in children: a review of randomized controlled trials. Ann Pharmacother. 2019;53(5):537-544.

The persistence of excitatory gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) signaling has been found in patients with ASD. Bumetanide is a sodium-potassium-chloride cotransporter 1 (NKCC1) antagonist that not only decreases intracellular chloride, but also aberrantly decreases GABA signaling. This potent loop diuretic is a proposed treatment for symptoms of ASD. James et al6 evaluated the safety and efficacy of bumetanide use in children with ASD.

Study design

- Researchers searched the PubMed and Ovid MEDLINE databases for the terms “autism” and “bumetanide” between 1946 and 2018. A total of 26 articles were screened by title, 7 were screened by full text, and 3 articles were included in the study. The remaining articles were excluded due to study design and use of non-human subjects.

- All 3 randomized controlled trials evaluated the effects of low-dose oral bumetanide (most common dose was 0.5 mg twice daily) in a total of 208 patients age 2 to 18 years.

- Measurement scales used in the 3 studies included the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS), Clinical Global Impressions Scale (CGI), Autism Behavioral Checklist (ABC), Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS), and Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic (ADOS-G).

Outcomes

- Bumetanide improved scores on multiple autism assessment scales, including CARS, but the degree of improvement was not consistent across the 3 trials.

- There was a statistically significant improvement in ASD symptoms as measured by CGI in all 3 trials, and statistically significant improvements on the ABC and SRS in 2 trials. No improvements were noted on the ADOS-G in any of the trials.

- No dose-effect correlation was identified, but hypokalemia and polyuria were more prevalent with higher doses of bumetanide.

Conclusion

- Low-dose oral bumetanide improved social communication, social interactions, and restricted interests in patients with moderate to severe ASD. However, the 3 trials used different evaluation methods and observed varying degrees of improvement, which makes it difficult to make recommendations for or against the use of bumetanide.

- Streamlined trials with a consensus on evaluation methodology are needed to draw conclusions about the efficacy and safety of bumetanide as a treatment for ASD.

Continue to: The use of SSRIs to target...

4. Li C, Bai Y, Jin C, et al. Efficacy and safety of fluoxetine in autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. Am J Ther. 2020;27(3):e312-e315.

The use of SSRIs to target symptoms of ASD has been long studied because many children with ASD have elevated serotonin levels. Several SSRIs, including fluoxetine, are FDA-approved for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety, and depression. Currently, no SSRIs are FDA-approved for treating ASD. In a meta-analysis, Li et al7 evaluated the use of fluoxetine for ASD.

Study design

- Two independent researchers searched for studies of fluoxetine treatment for ASD in Embase, Google Scholar, Ovid SP, and PubMed, with disagreement resolved by consensus.

- The researchers extracted the study design, patient demographics, and outcomes (inter-rater reliability kappa = 0.93). The primary outcomes were response rate of patients treated with fluoxetine, and change from baseline in ABC, ATEC, CARS, CGI, and Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) scores after fluoxetine treatment.

Outcomes

- This meta-analysis included 13 studies in which fluoxetine was used to treat a total of 303 patients with ASD. The median treatment duration was 6 months, the average age of participants was 15.23 years, and most participants (72%) were male.

- The response rate of patients treated with fluoxetine was 75%, with significant mean changes from baseline in ABC score (Helvetica Neue LT Std−3.42), ATEC score (Helvetica Neue LT Std−2.04), CGI score (Helvetica Neue LT Std−0.93), and Y-BOCS score (Helvetica Neue LT Std−1.86).

- A significantly higher incidence of hyperactivity/restlessness/agitation was noted with fluoxetine.

Conclusion

- Although 75% of participants responded to fluoxetine, the limitations of this meta-analysis included low power, inadequate quality of the included studies, and high statistical heterogeneity. In addition, the analysis found a high incidence of hyperactivity/restlessness associated with fluoxetine.

- Future randomized controlled studies may provide further clarification on managing symptoms of ASD with SSRIs.

Continue to: Irritability is a common comorbid...

5. Fallah MS, Shaikh MR, Neupane B, et al. Atypical antipsychotics for irritability in pediatric autism: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2019;29(3):168-180.

Irritability is a common comorbid symptom in children with ASD. Two second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs)—risperidone and aripiprazole—are FDA-approved for irritability associated with ASD. Fallah et al8 examined the efficacy of several SGAs for treating irritability.

Study design

- This review and meta-analysis included 8 studies identified from Medline, PsycINFO, and Embase from inception to March 2018. It included double-blind, randomized controlled trials that used the Aberrant Behavior Checklist Irritability (ABC-I) to measure irritability.

- The main outcome was change in degree of irritability.

- The 8 studies compared the efficacy of risperidone, aripiprazole, lurasidone, and placebo in a total of 878 patients.

Outcomes

- Risperidone reduced ABC-I scores more than aripiprazole, lurasidone, or placebo.

- Mean differences in ABC-I scores were Helvetica Neue LT Std−6.89 for risperidone, Helvetica Neue LT Std−6.62 for aripiprazole, and Helvetica Neue LT Std−1.61 for lurasidone.

Conclusion

- Risperidone and aripiprazole were efficacious and safe for children with ASD-associated irritability.

- Lurasidone may minimally improve irritability in children with ASD.

Continue to: Irritability and hyperactivity are common...

6. Mazahery H, Conlon CA, Beck KL, et al. A randomised controlled trial of vitamin D and omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in the treatment of irritability and hyperactivity among children with autism spectrum disorder. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2019;187:9-16.

Irritability and hyperactivity are common comorbid symptoms in children with ASD and have been linked to lower quality of life, poor adaptive functioning, and lower responsiveness to treatments when compared to children without comorbid problem behaviors. Mazahery et al9 evaluated the efficacy of vitamin D, omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA), or both on irritability and hyperactivity.

Study design

- In a 1-year, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 73 children age 2.5 to 8 years with ASD were randomly assigned to receive placebo; vitamin D, 2000 IU/d (VID); omega-3 LCPUFA, 722 mg/d (OM); or both in the aforementioned doses.

- The primary outcome was reduction in the Aberrant Behavior Checklist in the domains of irritability and hyperactivity. Caregivers also completed weekly surveys regarding adverse events, compliance, and utilization of behavioral therapies.

- Of 111 children enrolled, 73 completed the 12 months of treatment.

Outcomes

- Children who received OM and VID had a greater reduction in irritability than those who received placebo (P = .001 and P = .01, respectively).

- Children who received VID also had a reduction in irritability (P = .047).

- An explanatory analysis revealed that OM also reduced lethargy (based on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist) more significantly than placebo (P = .02 adjusted for covariates).

Conclusion

- Treatment with vitamin D, 2000 IU/d, reduced irritability and hyperactivity.

- Treatment with omega-3 LCPUFA, 722 mg/d, reduced hyperactivity and lethargy.

Continue to: Glutamatergic dysregulation has been...

7. Wink LK, Adams R, Horn PS, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled cross-over pilot study of riluzole for drug-refractory irritability in autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(9):3051-3060.

Glutamatergic dysregulation has been identified as a potential cause of ASD. Riluzole, a glutamatergic modulator that is FDA-approved for treating amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, is a drug of interest for the treatment of ASD-related irritability due to this proposed mechanism. Wink et al10 evaluated riluzole for irritability in patients with ASD.

Study design

- This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover pilot study evaluated the tolerability and safety of adjunctive riluzole treatment for drug-refractory irritability in 8 patients with ASD.

- Participants were age 12 to 25 years, had a diagnosis of ASD confirmed by the autism diagnostic observation schedule 2, and an ABC-I subscale score ≥18. Participants receiving ≥2 psychotropic medications or glutamatergic/GABA-modulating medications were excluded.

- Participants received either 5 weeks of riluzole followed by 5 weeks of placebo, or vice versa; both groups then had a 2-week washout period.

- Riluzole was started at 50 mg/d, and then increased in 50 mg/d–increments to a maximum of 200 mg/d by Week 4.

- Primary outcome measures were change in score on the ABC-I and CGI-I.

Outcomes

- No significant treatment effects were identified.

- All participants tolerated riluzole, 200 mg/d, but increased dosages did not result in a higher overall treatment effect.

- There were no clinically significant adverse effects or laboratory abnormalities.

Conclusion

- Riluzole, 200 mg/d, was well tolerated but had no significant effect on irritability in adolescents with ASD.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Christensen DL, Baio J, Van Naarden Braun K, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years: Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2012. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65(3):1-23.

3. Fung LK, Mahajan R, Nozzolillo A, et al. Pharmacologic treatment of severe irritability and problem behaviors in autism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2016;137(suppl 2):S124-S135.

4. Potter LA, Scholze DA, Biag HMB, et al. A randomized controlled trial of sertraline in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:810.

5. Gabis LV, Ben-Hur R, Shefer S, et al. Improvement of language in children with autism with combined donepezil and choline treatment. J Mol Neurosci. 2019;69(2):224-234.

6. James BJ, Gales MA, Gales BJ. Bumetanide for autism spectrum disorder in children: a review of randomized controlled trials. Ann Pharmacother. 2019;53(5) 537-544.

7. Li C, Bai Y, Jin C, et al. Efficacy and safety of fluoxetine in autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. Am J Ther. 2020;27(3):e312-e315.

8. Fallah MS, Shaikh MR, Neupane B, et al. Atypical antipsychotics for irritability in pediatric autism: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2019;29(3):168-180.

9. Mazahery H, Conlon CA, Beck KL, et al. A randomised controlled trial of vitamin D and omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in the treatment of irritability and hyperactivity among children with autism spectrum disorder. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2019;187:9-16.

10. Wink LK, Adams R, Horn PS, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled cross-over pilot study of riluzole for drug-refractory irritability in autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(9):3051-3060.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction, including deficits in social reciprocity, nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction, and skills in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships.1 In addition, the diagnosis of ASD requires the presence of restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities.

Initially, ASD was considered a rare condition. In recent years, the reported prevalence has increased substantially. The most recent estimated prevalence is 1 in 68 children at age 8, with a male-to-female ratio of 4 to 1.2

Behavioral interventions are considered to be the most effective treatment for the core symptoms of ASD. Pharmacologic interventions are used primarily to treat associated or comorbid symptoms rather than the core symptoms. Aggression, self-injurious behavior, and irritability are common targets of pharmacotherapy in patients with ASD. Studies have provided support for the use of antipsychotic agents to treat irritability and associated aggressive behaviors in patients with autism,3 but because these agents have significant adverse effects—including extrapyramidal side effects, somnolence, and weight gain—their use requires a careful risk/benefit assessment. Stimulants have also been shown to be effective in treating comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity symptoms. The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to manage repetitive behaviors and anxiety is also common.

Here, we review 7 recent studies of the pharmacologic management of ASD (Table).4-10 These studies examined the role of SSRIs (sertraline, fluoxetine), an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor (donepezil), atypical antipsychotics (risperidone, aripiprazole, lurasidone), natural supplements (vitamin D, omega-3), a diuretic (bumetanide), and a glutamatergic modulator (riluzole) in the treatment of ASD symptoms.

1. Potter LA, Scholze DA, Biag HMB, et al. A randomized controlled trial of sertraline in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:810.

Several studies have shown that SSRIs improve language development in children with Fragile X syndrome, based on the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL). A previously published trial involving children with Fragile X syndrome and comorbid ASD found that sertraline improved expressive language development. Potter et al4 examined the role of sertraline in children with ASD only.

Study Design

- In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 58 children age 24 to 72 months with ASD received low-dose sertraline or placebo for 6 months.

- Of the 179 participants who were screened for eligibility, 58 were included in the study. Of these 58 participants, 32 received sertraline and 26 received placebo. The numbers of participants who discontinued from the sertraline and placebo arms were 8 and 5, respectively.

- Among those in the sertraline group, participants age <48 months received 2.5 mg/d, and those age ≥48 months received 5 mg/d.

Outcomes

- No significant differences were found on the primary outcome (MSEL expressive language raw score and age-equivalent combined score) or secondary outcomes (including Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement [CGI-I] scale at 3 months and end of treatment), as per intent-to-treat analyses.

- Sertraline was well tolerated. There was no difference in adverse effects between treatment groups and no serious adverse events.

Conclusion

- Although potentially useful for language development in patients with Fragile X syndrome with comorbid ASD, SSRIs such as sertraline have not proven efficacious for improving expressive language in patients with non-syndromic ASD.

- While 6-month treatment with low-dose sertraline in young children with ASD appears safe, the long-term effects are unknown.

Continue to: Gabis et al5 examined the safety...

2. Gabis LV, Ben-Hur R, Shefer S, et al. Improvement of language in children with autism with combined donepezil and choline treatment. J Mol Neurosci. 2019;69(2):224-234.

Gabis et al5 examined the safety and efficacy of utilizing donepezil, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, plus a choline supplement to treat both core features and associated symptoms in children and adolescents with ASD.

Study design

- This 9-month randomized, double-blind trial included 60 children/adolescents with ASD who were randomly assigned to receive placebo or donepezil plus a choline supplement. Participants underwent a baseline evaluation (E1), 12 weeks of treatment and re-evaluation (E2), 6 months of washout, and a final evaluation (E3).

- The baseline and final evaluations assessed changes in language performance, adaptive functioning, sleep habits, autism severity, clinical impression, and intellectual abilities. The evaluation after 12 weeks of treatment (E2) included all of these measures except intellectual abilities.

Outcomes

- Patients treated with donepezil plus a choline supplement had significant improvement in receptive language skills between E1 and E3 (P = .003).

- Patients treated with donepezil plus a choline supplement had significant worsening in scores on the Autism Treatment Evaluation Checklist (ATEC) health/physical behavior subscale between E1 and E2 (P = .012) and between E1 and E3 (P = .021).

- Improvement in receptive language skills was significant only in patients age 5 to 10 years (P = .047), whereas worsening in ATEC health/physical behavior subscale score was significant only in patients age 10 to 16 years (P = .024).

- Patients treated with donepezil plus a choline supplement reported higher percentages of gastrointestinal disturbance when compared with placebo (P = .007), and patients in the adolescent subgroup had a significant increase in irritability (P = .035).

Conclusion

- Patients age 5 to 10 years treated with donepezil plus a choline supplement exhibited improved receptive language skills. This treatment was less effective in patients age >10 years, and this group also exhibited behavioral worsening.

- Gastrointestinal disturbances were the main adverse effect of treatment with donepezil plus a choline supplement.

Continue to: The persistence of excitatory...

3. James BJ, Gales MA, Gales BJ. Bumetanide for autism spectrum disorder in children: a review of randomized controlled trials. Ann Pharmacother. 2019;53(5):537-544.

The persistence of excitatory gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) signaling has been found in patients with ASD. Bumetanide is a sodium-potassium-chloride cotransporter 1 (NKCC1) antagonist that not only decreases intracellular chloride, but also aberrantly decreases GABA signaling. This potent loop diuretic is a proposed treatment for symptoms of ASD. James et al6 evaluated the safety and efficacy of bumetanide use in children with ASD.

Study design

- Researchers searched the PubMed and Ovid MEDLINE databases for the terms “autism” and “bumetanide” between 1946 and 2018. A total of 26 articles were screened by title, 7 were screened by full text, and 3 articles were included in the study. The remaining articles were excluded due to study design and use of non-human subjects.

- All 3 randomized controlled trials evaluated the effects of low-dose oral bumetanide (most common dose was 0.5 mg twice daily) in a total of 208 patients age 2 to 18 years.

- Measurement scales used in the 3 studies included the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS), Clinical Global Impressions Scale (CGI), Autism Behavioral Checklist (ABC), Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS), and Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic (ADOS-G).

Outcomes

- Bumetanide improved scores on multiple autism assessment scales, including CARS, but the degree of improvement was not consistent across the 3 trials.

- There was a statistically significant improvement in ASD symptoms as measured by CGI in all 3 trials, and statistically significant improvements on the ABC and SRS in 2 trials. No improvements were noted on the ADOS-G in any of the trials.

- No dose-effect correlation was identified, but hypokalemia and polyuria were more prevalent with higher doses of bumetanide.

Conclusion

- Low-dose oral bumetanide improved social communication, social interactions, and restricted interests in patients with moderate to severe ASD. However, the 3 trials used different evaluation methods and observed varying degrees of improvement, which makes it difficult to make recommendations for or against the use of bumetanide.

- Streamlined trials with a consensus on evaluation methodology are needed to draw conclusions about the efficacy and safety of bumetanide as a treatment for ASD.

Continue to: The use of SSRIs to target...

4. Li C, Bai Y, Jin C, et al. Efficacy and safety of fluoxetine in autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. Am J Ther. 2020;27(3):e312-e315.

The use of SSRIs to target symptoms of ASD has been long studied because many children with ASD have elevated serotonin levels. Several SSRIs, including fluoxetine, are FDA-approved for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety, and depression. Currently, no SSRIs are FDA-approved for treating ASD. In a meta-analysis, Li et al7 evaluated the use of fluoxetine for ASD.

Study design

- Two independent researchers searched for studies of fluoxetine treatment for ASD in Embase, Google Scholar, Ovid SP, and PubMed, with disagreement resolved by consensus.

- The researchers extracted the study design, patient demographics, and outcomes (inter-rater reliability kappa = 0.93). The primary outcomes were response rate of patients treated with fluoxetine, and change from baseline in ABC, ATEC, CARS, CGI, and Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) scores after fluoxetine treatment.

Outcomes

- This meta-analysis included 13 studies in which fluoxetine was used to treat a total of 303 patients with ASD. The median treatment duration was 6 months, the average age of participants was 15.23 years, and most participants (72%) were male.

- The response rate of patients treated with fluoxetine was 75%, with significant mean changes from baseline in ABC score (Helvetica Neue LT Std−3.42), ATEC score (Helvetica Neue LT Std−2.04), CGI score (Helvetica Neue LT Std−0.93), and Y-BOCS score (Helvetica Neue LT Std−1.86).

- A significantly higher incidence of hyperactivity/restlessness/agitation was noted with fluoxetine.

Conclusion

- Although 75% of participants responded to fluoxetine, the limitations of this meta-analysis included low power, inadequate quality of the included studies, and high statistical heterogeneity. In addition, the analysis found a high incidence of hyperactivity/restlessness associated with fluoxetine.

- Future randomized controlled studies may provide further clarification on managing symptoms of ASD with SSRIs.

Continue to: Irritability is a common comorbid...

5. Fallah MS, Shaikh MR, Neupane B, et al. Atypical antipsychotics for irritability in pediatric autism: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2019;29(3):168-180.

Irritability is a common comorbid symptom in children with ASD. Two second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs)—risperidone and aripiprazole—are FDA-approved for irritability associated with ASD. Fallah et al8 examined the efficacy of several SGAs for treating irritability.

Study design

- This review and meta-analysis included 8 studies identified from Medline, PsycINFO, and Embase from inception to March 2018. It included double-blind, randomized controlled trials that used the Aberrant Behavior Checklist Irritability (ABC-I) to measure irritability.

- The main outcome was change in degree of irritability.

- The 8 studies compared the efficacy of risperidone, aripiprazole, lurasidone, and placebo in a total of 878 patients.

Outcomes

- Risperidone reduced ABC-I scores more than aripiprazole, lurasidone, or placebo.

- Mean differences in ABC-I scores were Helvetica Neue LT Std−6.89 for risperidone, Helvetica Neue LT Std−6.62 for aripiprazole, and Helvetica Neue LT Std−1.61 for lurasidone.

Conclusion

- Risperidone and aripiprazole were efficacious and safe for children with ASD-associated irritability.

- Lurasidone may minimally improve irritability in children with ASD.

Continue to: Irritability and hyperactivity are common...

6. Mazahery H, Conlon CA, Beck KL, et al. A randomised controlled trial of vitamin D and omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in the treatment of irritability and hyperactivity among children with autism spectrum disorder. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2019;187:9-16.

Irritability and hyperactivity are common comorbid symptoms in children with ASD and have been linked to lower quality of life, poor adaptive functioning, and lower responsiveness to treatments when compared to children without comorbid problem behaviors. Mazahery et al9 evaluated the efficacy of vitamin D, omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA), or both on irritability and hyperactivity.

Study design

- In a 1-year, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 73 children age 2.5 to 8 years with ASD were randomly assigned to receive placebo; vitamin D, 2000 IU/d (VID); omega-3 LCPUFA, 722 mg/d (OM); or both in the aforementioned doses.

- The primary outcome was reduction in the Aberrant Behavior Checklist in the domains of irritability and hyperactivity. Caregivers also completed weekly surveys regarding adverse events, compliance, and utilization of behavioral therapies.

- Of 111 children enrolled, 73 completed the 12 months of treatment.

Outcomes

- Children who received OM and VID had a greater reduction in irritability than those who received placebo (P = .001 and P = .01, respectively).

- Children who received VID also had a reduction in irritability (P = .047).

- An explanatory analysis revealed that OM also reduced lethargy (based on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist) more significantly than placebo (P = .02 adjusted for covariates).

Conclusion

- Treatment with vitamin D, 2000 IU/d, reduced irritability and hyperactivity.

- Treatment with omega-3 LCPUFA, 722 mg/d, reduced hyperactivity and lethargy.

Continue to: Glutamatergic dysregulation has been...

7. Wink LK, Adams R, Horn PS, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled cross-over pilot study of riluzole for drug-refractory irritability in autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(9):3051-3060.

Glutamatergic dysregulation has been identified as a potential cause of ASD. Riluzole, a glutamatergic modulator that is FDA-approved for treating amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, is a drug of interest for the treatment of ASD-related irritability due to this proposed mechanism. Wink et al10 evaluated riluzole for irritability in patients with ASD.

Study design

- This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover pilot study evaluated the tolerability and safety of adjunctive riluzole treatment for drug-refractory irritability in 8 patients with ASD.

- Participants were age 12 to 25 years, had a diagnosis of ASD confirmed by the autism diagnostic observation schedule 2, and an ABC-I subscale score ≥18. Participants receiving ≥2 psychotropic medications or glutamatergic/GABA-modulating medications were excluded.

- Participants received either 5 weeks of riluzole followed by 5 weeks of placebo, or vice versa; both groups then had a 2-week washout period.

- Riluzole was started at 50 mg/d, and then increased in 50 mg/d–increments to a maximum of 200 mg/d by Week 4.

- Primary outcome measures were change in score on the ABC-I and CGI-I.

Outcomes

- No significant treatment effects were identified.

- All participants tolerated riluzole, 200 mg/d, but increased dosages did not result in a higher overall treatment effect.

- There were no clinically significant adverse effects or laboratory abnormalities.

Conclusion

- Riluzole, 200 mg/d, was well tolerated but had no significant effect on irritability in adolescents with ASD.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction, including deficits in social reciprocity, nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction, and skills in developing, maintaining, and understanding relationships.1 In addition, the diagnosis of ASD requires the presence of restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities.

Initially, ASD was considered a rare condition. In recent years, the reported prevalence has increased substantially. The most recent estimated prevalence is 1 in 68 children at age 8, with a male-to-female ratio of 4 to 1.2

Behavioral interventions are considered to be the most effective treatment for the core symptoms of ASD. Pharmacologic interventions are used primarily to treat associated or comorbid symptoms rather than the core symptoms. Aggression, self-injurious behavior, and irritability are common targets of pharmacotherapy in patients with ASD. Studies have provided support for the use of antipsychotic agents to treat irritability and associated aggressive behaviors in patients with autism,3 but because these agents have significant adverse effects—including extrapyramidal side effects, somnolence, and weight gain—their use requires a careful risk/benefit assessment. Stimulants have also been shown to be effective in treating comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity symptoms. The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to manage repetitive behaviors and anxiety is also common.

Here, we review 7 recent studies of the pharmacologic management of ASD (Table).4-10 These studies examined the role of SSRIs (sertraline, fluoxetine), an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor (donepezil), atypical antipsychotics (risperidone, aripiprazole, lurasidone), natural supplements (vitamin D, omega-3), a diuretic (bumetanide), and a glutamatergic modulator (riluzole) in the treatment of ASD symptoms.

1. Potter LA, Scholze DA, Biag HMB, et al. A randomized controlled trial of sertraline in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:810.

Several studies have shown that SSRIs improve language development in children with Fragile X syndrome, based on the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL). A previously published trial involving children with Fragile X syndrome and comorbid ASD found that sertraline improved expressive language development. Potter et al4 examined the role of sertraline in children with ASD only.

Study Design

- In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 58 children age 24 to 72 months with ASD received low-dose sertraline or placebo for 6 months.

- Of the 179 participants who were screened for eligibility, 58 were included in the study. Of these 58 participants, 32 received sertraline and 26 received placebo. The numbers of participants who discontinued from the sertraline and placebo arms were 8 and 5, respectively.

- Among those in the sertraline group, participants age <48 months received 2.5 mg/d, and those age ≥48 months received 5 mg/d.

Outcomes

- No significant differences were found on the primary outcome (MSEL expressive language raw score and age-equivalent combined score) or secondary outcomes (including Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement [CGI-I] scale at 3 months and end of treatment), as per intent-to-treat analyses.

- Sertraline was well tolerated. There was no difference in adverse effects between treatment groups and no serious adverse events.

Conclusion

- Although potentially useful for language development in patients with Fragile X syndrome with comorbid ASD, SSRIs such as sertraline have not proven efficacious for improving expressive language in patients with non-syndromic ASD.

- While 6-month treatment with low-dose sertraline in young children with ASD appears safe, the long-term effects are unknown.

Continue to: Gabis et al5 examined the safety...

2. Gabis LV, Ben-Hur R, Shefer S, et al. Improvement of language in children with autism with combined donepezil and choline treatment. J Mol Neurosci. 2019;69(2):224-234.

Gabis et al5 examined the safety and efficacy of utilizing donepezil, an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, plus a choline supplement to treat both core features and associated symptoms in children and adolescents with ASD.

Study design

- This 9-month randomized, double-blind trial included 60 children/adolescents with ASD who were randomly assigned to receive placebo or donepezil plus a choline supplement. Participants underwent a baseline evaluation (E1), 12 weeks of treatment and re-evaluation (E2), 6 months of washout, and a final evaluation (E3).

- The baseline and final evaluations assessed changes in language performance, adaptive functioning, sleep habits, autism severity, clinical impression, and intellectual abilities. The evaluation after 12 weeks of treatment (E2) included all of these measures except intellectual abilities.

Outcomes

- Patients treated with donepezil plus a choline supplement had significant improvement in receptive language skills between E1 and E3 (P = .003).

- Patients treated with donepezil plus a choline supplement had significant worsening in scores on the Autism Treatment Evaluation Checklist (ATEC) health/physical behavior subscale between E1 and E2 (P = .012) and between E1 and E3 (P = .021).

- Improvement in receptive language skills was significant only in patients age 5 to 10 years (P = .047), whereas worsening in ATEC health/physical behavior subscale score was significant only in patients age 10 to 16 years (P = .024).

- Patients treated with donepezil plus a choline supplement reported higher percentages of gastrointestinal disturbance when compared with placebo (P = .007), and patients in the adolescent subgroup had a significant increase in irritability (P = .035).

Conclusion

- Patients age 5 to 10 years treated with donepezil plus a choline supplement exhibited improved receptive language skills. This treatment was less effective in patients age >10 years, and this group also exhibited behavioral worsening.

- Gastrointestinal disturbances were the main adverse effect of treatment with donepezil plus a choline supplement.

Continue to: The persistence of excitatory...

3. James BJ, Gales MA, Gales BJ. Bumetanide for autism spectrum disorder in children: a review of randomized controlled trials. Ann Pharmacother. 2019;53(5):537-544.

The persistence of excitatory gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) signaling has been found in patients with ASD. Bumetanide is a sodium-potassium-chloride cotransporter 1 (NKCC1) antagonist that not only decreases intracellular chloride, but also aberrantly decreases GABA signaling. This potent loop diuretic is a proposed treatment for symptoms of ASD. James et al6 evaluated the safety and efficacy of bumetanide use in children with ASD.

Study design

- Researchers searched the PubMed and Ovid MEDLINE databases for the terms “autism” and “bumetanide” between 1946 and 2018. A total of 26 articles were screened by title, 7 were screened by full text, and 3 articles were included in the study. The remaining articles were excluded due to study design and use of non-human subjects.

- All 3 randomized controlled trials evaluated the effects of low-dose oral bumetanide (most common dose was 0.5 mg twice daily) in a total of 208 patients age 2 to 18 years.

- Measurement scales used in the 3 studies included the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS), Clinical Global Impressions Scale (CGI), Autism Behavioral Checklist (ABC), Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS), and Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic (ADOS-G).

Outcomes

- Bumetanide improved scores on multiple autism assessment scales, including CARS, but the degree of improvement was not consistent across the 3 trials.

- There was a statistically significant improvement in ASD symptoms as measured by CGI in all 3 trials, and statistically significant improvements on the ABC and SRS in 2 trials. No improvements were noted on the ADOS-G in any of the trials.

- No dose-effect correlation was identified, but hypokalemia and polyuria were more prevalent with higher doses of bumetanide.

Conclusion

- Low-dose oral bumetanide improved social communication, social interactions, and restricted interests in patients with moderate to severe ASD. However, the 3 trials used different evaluation methods and observed varying degrees of improvement, which makes it difficult to make recommendations for or against the use of bumetanide.

- Streamlined trials with a consensus on evaluation methodology are needed to draw conclusions about the efficacy and safety of bumetanide as a treatment for ASD.

Continue to: The use of SSRIs to target...

4. Li C, Bai Y, Jin C, et al. Efficacy and safety of fluoxetine in autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. Am J Ther. 2020;27(3):e312-e315.

The use of SSRIs to target symptoms of ASD has been long studied because many children with ASD have elevated serotonin levels. Several SSRIs, including fluoxetine, are FDA-approved for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety, and depression. Currently, no SSRIs are FDA-approved for treating ASD. In a meta-analysis, Li et al7 evaluated the use of fluoxetine for ASD.

Study design

- Two independent researchers searched for studies of fluoxetine treatment for ASD in Embase, Google Scholar, Ovid SP, and PubMed, with disagreement resolved by consensus.

- The researchers extracted the study design, patient demographics, and outcomes (inter-rater reliability kappa = 0.93). The primary outcomes were response rate of patients treated with fluoxetine, and change from baseline in ABC, ATEC, CARS, CGI, and Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) scores after fluoxetine treatment.

Outcomes

- This meta-analysis included 13 studies in which fluoxetine was used to treat a total of 303 patients with ASD. The median treatment duration was 6 months, the average age of participants was 15.23 years, and most participants (72%) were male.

- The response rate of patients treated with fluoxetine was 75%, with significant mean changes from baseline in ABC score (Helvetica Neue LT Std−3.42), ATEC score (Helvetica Neue LT Std−2.04), CGI score (Helvetica Neue LT Std−0.93), and Y-BOCS score (Helvetica Neue LT Std−1.86).

- A significantly higher incidence of hyperactivity/restlessness/agitation was noted with fluoxetine.

Conclusion

- Although 75% of participants responded to fluoxetine, the limitations of this meta-analysis included low power, inadequate quality of the included studies, and high statistical heterogeneity. In addition, the analysis found a high incidence of hyperactivity/restlessness associated with fluoxetine.

- Future randomized controlled studies may provide further clarification on managing symptoms of ASD with SSRIs.

Continue to: Irritability is a common comorbid...

5. Fallah MS, Shaikh MR, Neupane B, et al. Atypical antipsychotics for irritability in pediatric autism: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2019;29(3):168-180.

Irritability is a common comorbid symptom in children with ASD. Two second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs)—risperidone and aripiprazole—are FDA-approved for irritability associated with ASD. Fallah et al8 examined the efficacy of several SGAs for treating irritability.

Study design

- This review and meta-analysis included 8 studies identified from Medline, PsycINFO, and Embase from inception to March 2018. It included double-blind, randomized controlled trials that used the Aberrant Behavior Checklist Irritability (ABC-I) to measure irritability.

- The main outcome was change in degree of irritability.

- The 8 studies compared the efficacy of risperidone, aripiprazole, lurasidone, and placebo in a total of 878 patients.

Outcomes

- Risperidone reduced ABC-I scores more than aripiprazole, lurasidone, or placebo.

- Mean differences in ABC-I scores were Helvetica Neue LT Std−6.89 for risperidone, Helvetica Neue LT Std−6.62 for aripiprazole, and Helvetica Neue LT Std−1.61 for lurasidone.

Conclusion

- Risperidone and aripiprazole were efficacious and safe for children with ASD-associated irritability.

- Lurasidone may minimally improve irritability in children with ASD.

Continue to: Irritability and hyperactivity are common...

6. Mazahery H, Conlon CA, Beck KL, et al. A randomised controlled trial of vitamin D and omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in the treatment of irritability and hyperactivity among children with autism spectrum disorder. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2019;187:9-16.

Irritability and hyperactivity are common comorbid symptoms in children with ASD and have been linked to lower quality of life, poor adaptive functioning, and lower responsiveness to treatments when compared to children without comorbid problem behaviors. Mazahery et al9 evaluated the efficacy of vitamin D, omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA), or both on irritability and hyperactivity.

Study design

- In a 1-year, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 73 children age 2.5 to 8 years with ASD were randomly assigned to receive placebo; vitamin D, 2000 IU/d (VID); omega-3 LCPUFA, 722 mg/d (OM); or both in the aforementioned doses.

- The primary outcome was reduction in the Aberrant Behavior Checklist in the domains of irritability and hyperactivity. Caregivers also completed weekly surveys regarding adverse events, compliance, and utilization of behavioral therapies.

- Of 111 children enrolled, 73 completed the 12 months of treatment.

Outcomes

- Children who received OM and VID had a greater reduction in irritability than those who received placebo (P = .001 and P = .01, respectively).

- Children who received VID also had a reduction in irritability (P = .047).

- An explanatory analysis revealed that OM also reduced lethargy (based on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist) more significantly than placebo (P = .02 adjusted for covariates).

Conclusion

- Treatment with vitamin D, 2000 IU/d, reduced irritability and hyperactivity.

- Treatment with omega-3 LCPUFA, 722 mg/d, reduced hyperactivity and lethargy.

Continue to: Glutamatergic dysregulation has been...

7. Wink LK, Adams R, Horn PS, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled cross-over pilot study of riluzole for drug-refractory irritability in autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(9):3051-3060.

Glutamatergic dysregulation has been identified as a potential cause of ASD. Riluzole, a glutamatergic modulator that is FDA-approved for treating amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, is a drug of interest for the treatment of ASD-related irritability due to this proposed mechanism. Wink et al10 evaluated riluzole for irritability in patients with ASD.

Study design

- This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover pilot study evaluated the tolerability and safety of adjunctive riluzole treatment for drug-refractory irritability in 8 patients with ASD.

- Participants were age 12 to 25 years, had a diagnosis of ASD confirmed by the autism diagnostic observation schedule 2, and an ABC-I subscale score ≥18. Participants receiving ≥2 psychotropic medications or glutamatergic/GABA-modulating medications were excluded.

- Participants received either 5 weeks of riluzole followed by 5 weeks of placebo, or vice versa; both groups then had a 2-week washout period.

- Riluzole was started at 50 mg/d, and then increased in 50 mg/d–increments to a maximum of 200 mg/d by Week 4.

- Primary outcome measures were change in score on the ABC-I and CGI-I.

Outcomes

- No significant treatment effects were identified.

- All participants tolerated riluzole, 200 mg/d, but increased dosages did not result in a higher overall treatment effect.

- There were no clinically significant adverse effects or laboratory abnormalities.

Conclusion

- Riluzole, 200 mg/d, was well tolerated but had no significant effect on irritability in adolescents with ASD.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Christensen DL, Baio J, Van Naarden Braun K, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years: Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2012. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65(3):1-23.

3. Fung LK, Mahajan R, Nozzolillo A, et al. Pharmacologic treatment of severe irritability and problem behaviors in autism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2016;137(suppl 2):S124-S135.

4. Potter LA, Scholze DA, Biag HMB, et al. A randomized controlled trial of sertraline in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:810.

5. Gabis LV, Ben-Hur R, Shefer S, et al. Improvement of language in children with autism with combined donepezil and choline treatment. J Mol Neurosci. 2019;69(2):224-234.

6. James BJ, Gales MA, Gales BJ. Bumetanide for autism spectrum disorder in children: a review of randomized controlled trials. Ann Pharmacother. 2019;53(5) 537-544.

7. Li C, Bai Y, Jin C, et al. Efficacy and safety of fluoxetine in autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. Am J Ther. 2020;27(3):e312-e315.

8. Fallah MS, Shaikh MR, Neupane B, et al. Atypical antipsychotics for irritability in pediatric autism: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2019;29(3):168-180.

9. Mazahery H, Conlon CA, Beck KL, et al. A randomised controlled trial of vitamin D and omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in the treatment of irritability and hyperactivity among children with autism spectrum disorder. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2019;187:9-16.

10. Wink LK, Adams R, Horn PS, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled cross-over pilot study of riluzole for drug-refractory irritability in autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(9):3051-3060.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Christensen DL, Baio J, Van Naarden Braun K, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years: Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2012. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65(3):1-23.

3. Fung LK, Mahajan R, Nozzolillo A, et al. Pharmacologic treatment of severe irritability and problem behaviors in autism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2016;137(suppl 2):S124-S135.

4. Potter LA, Scholze DA, Biag HMB, et al. A randomized controlled trial of sertraline in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:810.

5. Gabis LV, Ben-Hur R, Shefer S, et al. Improvement of language in children with autism with combined donepezil and choline treatment. J Mol Neurosci. 2019;69(2):224-234.

6. James BJ, Gales MA, Gales BJ. Bumetanide for autism spectrum disorder in children: a review of randomized controlled trials. Ann Pharmacother. 2019;53(5) 537-544.

7. Li C, Bai Y, Jin C, et al. Efficacy and safety of fluoxetine in autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis. Am J Ther. 2020;27(3):e312-e315.

8. Fallah MS, Shaikh MR, Neupane B, et al. Atypical antipsychotics for irritability in pediatric autism: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2019;29(3):168-180.

9. Mazahery H, Conlon CA, Beck KL, et al. A randomised controlled trial of vitamin D and omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in the treatment of irritability and hyperactivity among children with autism spectrum disorder. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2019;187:9-16.

10. Wink LK, Adams R, Horn PS, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled cross-over pilot study of riluzole for drug-refractory irritability in autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(9):3051-3060.

The psychiatric consequences of COVID-19: 8 Studies

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the novel coronavirus that is causing the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, was first reported in late 2019.1 As of mid-October 2020, >39 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 had been reported worldwide, and the United States was the most affected country with >8 million confirmed cases.2 Although the reported symptoms of COVID-19 are primarily respiratory with acute respiratory distress syndrome, SARS-CoV-2 has also been shown to affect other organs, including the brain, and there are emerging reports of neurologic symptoms due to COVID-19.3

Psychological endurance will be a challenge that many individuals will continue to face during and after the pandemic. Physical and social isolation, the disruption of daily routines, financial stress, food insecurity, and numerous other potential triggers for stress response have all been intensified due to this pandemic, creating a situation in which many individuals’ mental well-being and stability is likely to be threatened. The uncertain environment is likely to increase the frequency and/or severity of mental health problems worldwide. Psychiatric symptoms such as anxiety and depression have been reported among patients with SARS-CoV-1 during the previous severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic.4

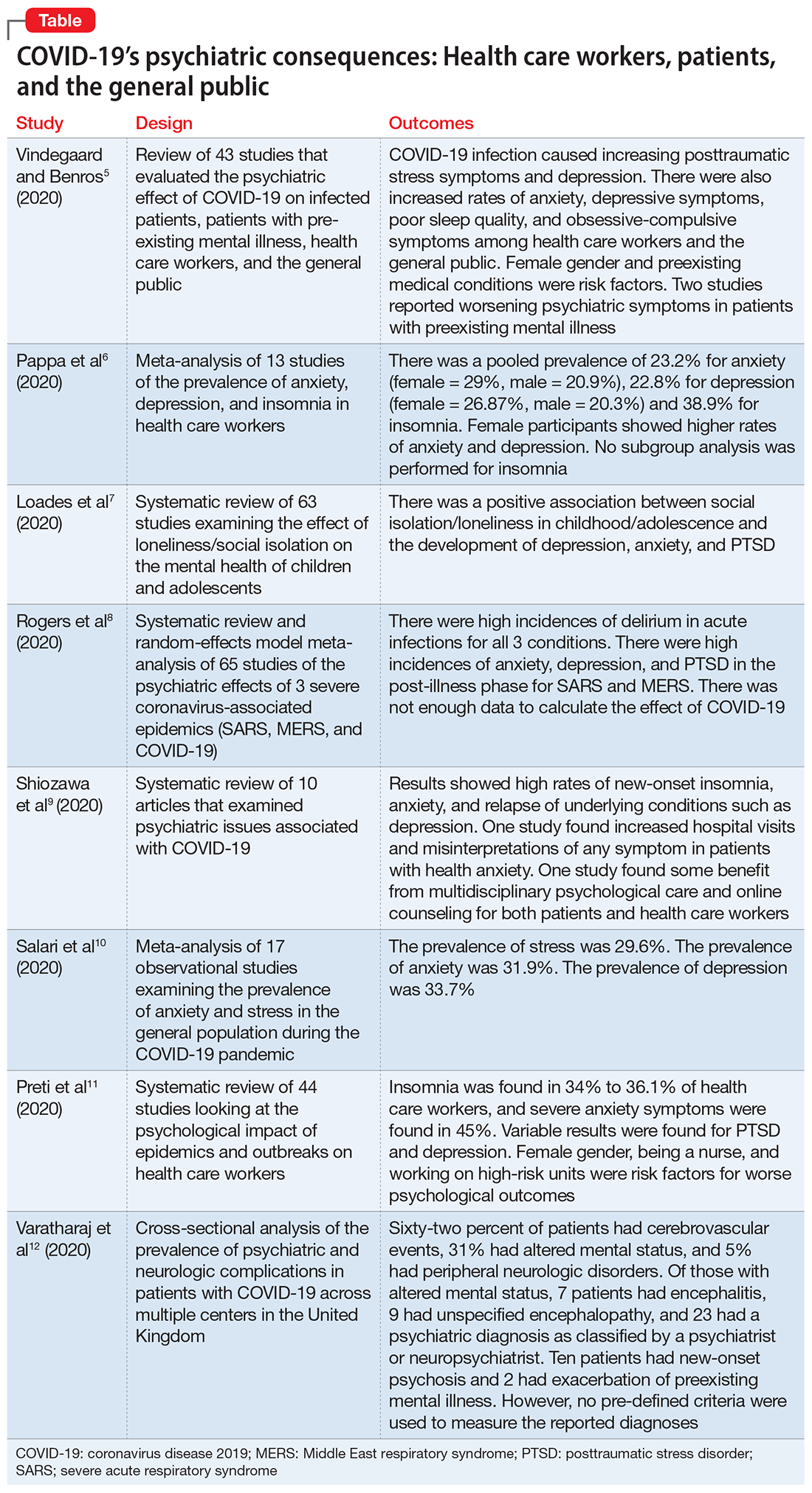

In this article, we summarize 8 recent studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses to provide an overview of the psychiatric consequences of COVID-19. These studies are summarized in the Table.5-12 Clearly, the studies reviewed here are preliminary evidence, and our understanding of COVID-19’s effects on mental health, particularly its long-term sequelae, is certain to evolve with future research. However, these 8 studies describe how COVID-19 is currently affecting mental health among health care workers, patients, and the general public.

1. Vindegaard N, Benros ME. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:531-542.

Vindegaard and Benros5 conducted a systematic review of the literature to characterize the impact of COVID-19–related psychiatric complications and COVID-19’s effect on the mental health of patients infected with COVID-19, as well as non-infected individuals.

Study design

- This systematic review included 43 studies that measured psychiatric disorders or symptoms in patients with COVID-19 and in a non-infected group.

- The non-infected group consisted of psychiatric patients, health care workers, and the general population.

- The review excluded studies with participants who were children, adolescents, or older adults, or had substance abuse or somatic disorders.

- Only 2 studies included patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection. Of the remaining 41 studies, 2 studies examined the indirect effects of the pandemic on psychiatric patients, 20 studies examined health care workers, and 19 studies examined the general population. Eighteen of the studies were case-control studies and 25 had no control group

Patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection. One case-control study showed an increased prevalence of depression in patients with COVID-19 who had recently recovered (29.2%) compared with participants who were in quarantine (9.8%). The other study showed posttraumatic stress symptoms in 96% of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 who were stable.

Continue to: Patients with preexisting psychiatric disorders

Patients with preexisting psychiatric disorders. Two studies found increased symptoms of psychiatric disorders.

Health care workers. Depression (6 studies) and anxiety symptoms (8 studies) were increased among health care workers compared with the general public or administrative staff. However, 2 studies found no difference in these symptoms among health care workers compared with the general public. Poor sleep quality and more obsessive-compulsive symptoms were reported in health care workers compared with the general public.

General public. Compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic, lower psychological well-being and increased rates of depression and anxiety were noted among the general public. Higher rates of anxiety and depression were also found in parents of children who were hospitalized during the pandemic compared with prior to the pandemic. One study found no difference between being in quarantine or not.

- Current or prior medical illness was associated with higher rates of anxiety and depression. One study found higher social media exposure was associated with increased anxiety and depression. Female health care workers had higher rates of anxiety and depression symptoms.

Conclusions/limitations

This systematic review included 39 studies from Asia and 4 from Europe, but none from other continents, which may affect the external validity of the results. Most of the studies included were not case-controlled, which limits the ability to comment on association. Because there is little research on this topic, only 2 of the studies focused on psychiatric symptoms in patients with COVID-19. In most studies, the reporting of psychiatric disorders was vague and only a few studies used assessment tools, such as the General Anxiety Disorder-7 or the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, for reporting depression and anxiety.

2. Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:901-907.

Pappa et al6 examined the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of health care workers, with specific focus on the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and insomnia.

Continue to: Study design

Study design

- Researchers searched for studies on PubMed, Medline, and Google Scholar. A random effect meta-analysis was used on the included 13 cross-sectional studies with a total of 33,062 participants. Twelve of the included studies were conducted in China and 1 in Singapore.

- Evaluation of the risk of bias of included studies was assessed using a modified form of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), with a score >3 considered as low risk of bias.

Outcomes

- Results were categorized by gender, rating scales, severity of depression, and professional groups for subgroup analysis.

- The primary outcomes were prevalence (p), confidence intervals (CI), and percentage prevalence (p × 100%). Studies with a low risk of bias were sub-analyzed again (n = 9).

- Anxiety was evaluated in 12 studies, depression in 10 studies, and insomnia in 5 studies (all 5 studies had a low risk of bias).

- There was a pooled prevalence of 23.2% for anxiety (29% female, 20.9% male), 22.8% for depression (26.87% female, 20.3% male), and 38.9% for insomnia. Female participants showed higher rates of anxiety and depression, while no subgroup analysis was performed for insomnia.

- The subgroup analysis of pooled data after excluding each study showed that no single study had >2% effect on the pooled analysis.

- The subgroup analysis by gender, professional group, and severity suggested that there was an increased prevalence of anxiety and depression in female health care workers, which was consistent with the increased prevalence in the general population.

Conclusions/limitations

There was a questionable effect of between-study heterogeneity. Different studies used different rating scales and different cutoff points on the same scales, which might make the results of pooled analysis unreliable, or might be assumed to increase the confidence. Despite the use of different scales and cutoff points, there was still a high prevalence of anxiety, depression, and insomnia. All studies were conducted in a single geographical region (12 in China and 1 in Singapore). None of the included studies had a control group, either from the general population or compared with pre-COVID-19 rates of depression, anxiety, and insomnia in health care workers.

3. Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, et al. Rapid systematic review: the impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19 [published online June 3, 2020]. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;S0890-8567(20)30337-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to long periods of isolation/quarantine, social distancing, and school closures, all which have resulted in significant upheaval of the lives of children and adolescents. Loades et al7 explored the impact of loneliness and disease-containment measures related to the COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents.

Study design

- Researchers conducted a systematic review of 63 studies examining the impact of loneliness or disease-containment measures on healthy children and adolescents. located through a search of Medline, PsycINFO, and Web of Science. Sixty-one studies were observational, and 2 were interventional.

- The search yielded studies published between 1946 and March 29, 2020.

- The quality of studies was assessed using the National Institutes of Health quality assessment tool.

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- Results by mental health symptom or disorder were categorized as follows:

Depression. Forty-five studies examined depressive symptoms and loneliness; only 6 studies included children age <10. Most reported a moderate to large correlation (0.12 ≤ r ≤ 0.81), and most of them included a measure of depressive symptoms. The association was stronger in older and female participants. Loneliness was associated with depression in 12 longitudinal studies that followed participants for 1 to 3 years. However, 3 studies (2 in children and 1 in adolescents) found no association between loneliness and depression at follow-up.

Anxiety. Twenty-three studies examined symptoms of anxiety and found a small to moderate correlation between loneliness/social isolation and anxiety (0.18 ≤ r ≤ 0.54), with duration of loneliness being more strongly associated with anxiety than intensity of loneliness. However, social anxiety or generalized anxiety were associated more with loneliness ([0.33 ≤ r ≤ 0.72] and [r = 0.37, 0.40], respectively). Three longitudinal studies found associations between loneliness and subsequent anxiety, and 1 study did not find an association between loneliness at age 5 and increased anxiety at age 12.

Mental health and well-being. Two studies found negative associations between social isolation/loneliness and well-being and mental health.

Conclusions/limitations

There is decent evidence of a strong association between loneliness/social isolation in childhood/adolescence and the development of depression, with some suggestion of increased rates in females. However, there was a small to moderate association with anxiety with increased rates in males. The length of social isolation was a strong predictor of future mental illness. Children who experienced enforced quarantine were 5 times more likely to require mental health services for posttraumatic stress symptoms.

Continue to: The compiled evidence presented in this study...

The compiled evidence presented in this study looked at previous similar scenarios of enforced social isolations; however, it cannot necessarily predict the effect of COVID-19–associated social distancing measures. Most of the studies included were cross-sectional studies and did not control for confounders. Social isolation in childhood or adolescence may be associated with developing mental health problems later in life and should be considered when implementing school closures and switching to online classes. Loades et al7 suggested that the increased rate of electronic communication and use of social media in children and adolescents may mitigate this predicted effect of social isolation.

4. Rogers JP, Chesney E, Oliver D, et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(7):611-627.

To identify possible psychiatric and neuropsychiatric implications of the COVID-19 pandemic, Rogers et al8 examined 2 previous coronavirus epidemics, SARS and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), and COVID-19.

Study design

- Researchers conducted a random-effects model meta-analysis and systematic review of 65 studies and 7 preprints from 10 countries, including approximately 3,559 case studies of psychiatric and neuropsychiatric symptoms in participants infected with the 3 major coronavirus-induced illnesses (SARS, MERS, and COVID-19).

- Pure neurologic complications and indirect effects of the epidemics were excluded.

- The systematic review followed PRISMA guidelines.

- The quality of the studies was assessed using the NOS.

Outcomes

- Outcomes measured were psychiatric signs or symptoms; symptom severity; diagnoses based on ICD-10, DSM-IV, the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders (third edition), or psychometric scales; quality of life; and employment.

- Results were stratified as acute or post-illness:

Acute illness. Delirium was the most frequently reported symptom in all 3 coronavirus infections. Depression, anxiety, or insomnia were also reported in MERS and SARS infections. Mania was described in SARS, but it was almost entirely present in cases treated with high-dose corticosteroids, which are not used routinely for COVID-19.

Continue to: Post-illness

Post-illness. There was increased incidence of depression, anxiety, fatigue, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the post-illness stage of previous coronavirus epidemics (SARS and MERS), but there was no control group for comparison. There was not enough data available for COVID-19.

Conclusions/limitations

Three studies were deemed to be of high quality, 32 were low quality, and 30 were moderate quality. Despite the high incidence of psychiatric symptoms in previous coronavirus infections, it was difficult to draw conclusions due to a lack of adequate control groups and predominantly low-quality studies. The difference in treatment strategies, such as the use of high-dose corticosteroids for MERS and SARS, but not for COVID-19, made it difficult to accurately predict a response for COVID-19 based on previous epidemics.

5. Shiozawa P, Uchida RR. An updated systematic review on the coronavirus pandemic: lessons for psychiatry. Braz J Psychiatry. 2020;42(3):330-331.

Schiozawa et al9 conducted a systematic review of articles to identify psychiatric issues during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Study design

- Researchers conducted a systematic review of 10 articles (7 articles from China, 1 from the United States, 1 from Japan, and 1 from Korea) that described strategies for coping with the COVID-19 pandemic and/or provided a descriptive analysis of the clinical scenario, with an emphasis on psychiatric comorbidities.

- The study used PRISMA guidelines to summarize the findings of those 10 studies. There were no pre-set outcomes or inclusion criteria.

Outcomes

- The compiled results of the 10 studies showed high rates of new-onset insomnia, anxiety, and relapse of underlying conditions such as depression.

- One study found increased hospital visits and misinterpretations of any symptom in patients with health anxiety (health anxiety was not defined).

- One study found some benefit from multidisciplinary psychological care and online counseling for both patients and health care workers.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

Because each of the 10 studies examined extremely different outcomes, researchers were unable to compile data from all studies to draw a conclusion.

6. Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Health. 2020;16(1):57.

Salari et al10 examined the prevalence of stress, anxiety, and depression in the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Study design

- Researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 17 observational studies examining the prevalence of anxiety and stress in the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. The STROBE checklist was used to assess the quality of studies.

- Only studies judged as medium to high quality were included in the analysis.

Outcomes

- The prevalence of stress was 29.6% (5 studies, sample size 9,074 individuals).

- The prevalence of anxiety was 31.9% (17 studies, sample size 63,439 individuals).

- The prevalence of depression was 33.7% (14 studies, sample size of 44,531 individuals).

- A sub-analysis of rates by continent revealed that Asia had highest prevalence of anxiety and depression (32.9% and 35.3%, respectively). Europe had the highest rates of stress (31.9%).

Conclusions/limitations

There is an increased prevalence of anxiety, stress, and depression in the general population amid the COVID-19 pandemic. None of the included studies compared rates to before the pandemic. Most studies used online surveys, which increased the chance of sample bias. Most studies originated from China and Iran, which had the highest rates of infection when this review was conducted.

Continue to: #7

7. Preti E, Di Mattei V, Perego G, et al. The psychological impact of epidemic and pandemic outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review of the evidence. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22(8):43.

Preti et al11 performed a review of the literature to determine the impact of epidemic/pandemic outbreaks on health care workers’ mental health.

Study design

- Researchers conducted a rapid systematic review of 44 studies examining the psychological impact of epidemic/pandemic outbreaks on health care workers.

- Of the 44 studies, 27 (62%) referred to the SARS outbreak, 5 (11%) referred to the MERS outbreak, 5 (11%) referred to the COVID-19 outbreak, 3 (7%) referred to the influenza A virus subtype H1N1 outbreak, 3 (7%) referred to the Ebola virus disease outbreak, and 1 (2%) referred to the Asian lineage avian influenza outbreak.

Outcomes

- During these outbreaks, insomnia was found in 34% to 36.1% of health care workers, and severe anxiety symptoms in 45%.

- The prevalence of PTSD-like symptoms among health care workers during the outbreaks was 11% to 73.4%. Studies of the COVID-19 pandemic reported the highest prevalence of PTSD-like symptoms (71.5% to 73%). After 1 to 3 years following an outbreak, 10% to 40% of health care workers still had significant PTSD-like symptoms.

- Anxiety was reported in 45% of health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- A sub-analysis revealed a positive association between anxiety, PTSD, and stress symptoms and being female gender, being a nurse, and working on high-risk units.

- Perceived organizational support and confidence in protective measures were negatively associated with psychological symptoms.

Conclusions/limitations

Lessons from previous outbreaks and early data from the COVID-19 pandemic suggest that health care workers experience higher levels of psychological symptoms during outbreaks. Findings of this study suggest that organizational support and confidence in protective measures can mitigate this effect. To help preserve the well-being of health care workers, adequate training should be provided, appropriate personal protective equipment should be readily available, and support services should be well established.

8. Varatharaj A, Thomas N, Ellul MA, et al. Neurological and neuropsychiatric complications of COVID-19 in 153 patients: a UK-wide surveillance study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):875-882.

Varatharaj et al12 conducted a surveillance study in patients in the United Kingdom to understand the breadth of neurologic complications of COVID-19.

Continue to: Study design

Study design

- Researchers performed a cross-sectional analysis of the prevalence of psychiatric and neurologic complications in patients with COVID-19 across multiple centers in United Kingdom. Data were collected through the anonymous online reporting portals of several major neurology and psychiatric associations. Retrospective reporting was allowed.

- Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection was defined as:

Confirmed COVID-19 (114 cases) if polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of respiratory samples (eg, nasal or throat swab) or CSF was positive for viral RNA or if serology was positive for anti-SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin M (IgM) or immunoglobulin G (IgG).

Probable COVID-19 (6 cases) if a chest radiograph or chest CT was consistent with COVID-19 but PCR and serology were negative or not performed.

Possible COVID-19 (5 cases) if the disease was suspected on clinical grounds by the notifying clinician, but PCR, serology, and chest imaging were negative or not performed.

Outcomes

- Sixty-two percent of patients presented with cerebrovascular events (intracerebral hemorrhage, ischemic stroke, vasculitis, or other). Thirty-one percent of patients presented with altered mental status (AMS), and 5% had peripheral neurologic disorders.

- Of those with AMS, 18% (7 patients) had encephalitis, 23% (9 patients) had unspecified encephalopathy, and 59% (23 patients) had a psychiatric diagnosis as classified by the notifying psychiatrist or neuropsychiatrist. Ten patients (43%) of the 23 patients with neuropsychiatric disorders had new-onset psychosis, while only 2 patients had an exacerbation of a preexisting mental illness.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations

Conclusions/limitations

This study had an over-representation of older adults. There was no control group for comparison, and the definition of confirmed COVID-19 included a positive IgM or IgG without a positive PCR or chest imaging. Although all psychiatric conditions reported were confirmed by a psychiatrist or neuropsychiatrist, there were no pre-defined criteria used for reported diagnoses.

Bottom Line

Evidence from studies of previous outbreaks and early data from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic suggest that during outbreaks, health care workers experience higher levels of psychological symptoms than the general population. There has been an increased prevalence of anxiety, stress, poor sleep quality, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and depression among the general population during the pandemic. COVID-19 can also impact the CNS directly and result in delirium, cerebrovascular events, encephalitis, unspecified encephalopathy, altered mental status, or peripheral neurologic disorders. Patients with preexisting psychiatric disorders are likely to have increased symptoms and should be monitored for breakthrough symptoms and acute exacerbations.

Related Resources

- Ryznar E. Evaluating patients’ decision-making capacity during COVID-19. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(10):34-40.

- Freudenreich O, Kontos N, Querques J. COVID-19 and patients with serious mental illness. 2020;19(9):24-27,33-39.

- Esterwood E, Saeed SA. Past epidemics, natural disasters, COVID19, and mental health: learning from history as we deal with the present and prepare for the future [published online August 16, 2020]. Psychiatr Q. 2020:1-13. doi: 10.1007/s11126-020-09808-4.

1. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et. al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506.

2. John Hopkins University & Medicine. Coronavirus Resource Center. 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu. Accessed October 16, 2020.