User login

Anxiety and depression: Easing the burden in COPD patients

› Initiate both pharmacologic and psychological therapies for anxiety or depression coexisting with COPD to improve patient outcomes. B

› Consider buspirone as an alternative to benzodiazepines for anxiety coexistent with COPD. B

› Consider motivational interviewing as a behavioral approach to help patients who are ambivalent about or resistant to change. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › A 66-year-old man you have seen many times for issues related to his chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) comes in to your clinic for a routine visit. He has been taking budesonide/formoterol twice a day for the last 3 years; however, he has not always been compliant with his medications and has been hospitalized within the last 6 months for disease exacerbations. Today, he says he has difficulty falling asleep and often becomes short of breath, even when physically inactive. His wife, who is accompanying him today, tells you he has become increasingly distant over the past few months and is not as engaged at family outings, which he attributes to labored breathing. They’re both concerned about this change and ask for advice.

Despite the increased awareness that generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) are common comorbidities of COPD, they remain underdiagnosed and undertreated in patients with COPD. The results are increased rates of symptom exacerbation and rehospitalization.1 Family physicians, who are the primary caregivers for most patients with the disease,2 can maximize patients’ quality of life by recognizing comorbid mental illness, motivating and engaging patients in their disease management, and initiating appropriate treatment.

Anxiety and depression in COPD: A 2-way street

Several studies have assessed the prevalence of psychological disorders in patients with COPD. Affective disorders, mainly GAD and MDD, are the ones most commonly associated with poor COPD prognoses.3,4 GAD is at least 3 times more prevalent in patients with COPD than in the general US population,5 reaching upwards of 55%.1,6 Prevalence of MDD is also high, affecting approximately 40% of patients with the disease.1

GAD and MDD are more prevalent as comorbidities of COPD than they are with other chronic diseases such as orthopedic conditions, pulmonary tuberculosis, hypertension and heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and cancer.5,7-9 Patients with COPD, more so than patients with other serious chronic diseases, report heightened edginess, anxiousness, tiredness, distractibility, and irritability,5 perhaps owing in part to breathlessness and “air hunger.”10

The connection between COPD and GAD or MDD is not unidirectional, with progression of lung disease exacerbating its psychological comorbidities. The interaction is reciprocal, as clarified by Atlantis, et al, in a 2013 systematic review and meta-analysis that assessed key variables in the development of COPD and GAD or MDD.11

COPD increases the risk of MDD, which is associated with increased tobacco consumption, poor adherence with COPD medications, and decreased physical activity.11 Compounding the problem of inactivity is the fact that COPD—particularly longstanding disease—can lead to volume reductions in the anterior cingulate cortex of patients, which correlates with a persistent fear of performing physical activity.12 MDD in the setting of COPD also complicates the already complex interplay between nicotine dependence and attempts at smoking cessation.11

GAD/MDD worsens COPD outcomes

Comorbid GAD and MDD increase demands on our health care system and decrease the quality of life for patients with COPD. Anxious or depressed patients have higher 30-day readmission rates and less frequent outpatient follow-up than COPD patients without these mental comorbidities.6 Patients with comorbidities tend to have a higher prevalence of systemic symptoms independent of COPD severity,7 exhibit poorer physical and social functioning,13 and experience greater impairment of quality of life than patients with lung dysfunction alone.1,14 Patients with GAD or MDD have a 43% increased risk of any adverse COPD outcome, which can include exacerbations, COPD-related diagnoses (eg, emphysema), new anxiety or depression events, and death.11 Specifically, the risk of a COPD exacerbation rises by 31% in patients with comorbid GAD or MDD, and risk of death in those with comorbid MDD increases by 83%.11

GAD or MDD with COPD increases health care utilization and costs per patient when compared with patients who have COPD alone.9 Annual physician visits, emergency-room visits, and hospitalizations for any cause are higher in anxious or depressed COPD patients, and they have a 77% increased chance annually of a COPD-related hospitalization.9 Annual COPD-related health care costs for patients with GAD or MDD are significantly higher than the average COPD-related costs for patients without depression or anxiety, leading to significantly increased all-cause health care costs: $28,961 vs $22,512.9 Addressing and managing comorbid GAD or MDD in COPD patients could substantially reduce health care costs.

Be vigilant for anxiety, depression—even when COPD is mild

One reason comorbid GAD or MDD may be overlooked and underdiagnosed is that the symptoms can overlap those of COPD. In cases where suspicion of GAD or MDD is warranted, providers must keep separate the diagnostic inquiries for COPD and these comorbidities.6

Somatic symptoms of anxiety, such as hyperventilation, shortness of breath, and sweating, may easily be attributed to pulmonary disease instead of a psychological disorder. Differentiating the 2 processes becomes more difficult with patients younger than 60 years, as they are more likely to experience symptoms of GAD or MDD than older patients, regardless of COPD severity.15 Therefore, when assessing COPD patients, physicians need to be more vigilant for anxiety and depression, even in the mildest cases.14

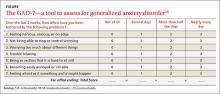

Several methods exist for assessing anxiety and depression, including the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener 7 (GAD-7) and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) 2 or 9.16 All PHQ and GAD-7 screeners and translations are downloadable from www.phqscreeners.com/select-screener and permission is not required to reproduce, translate, display, or distribute them (FIGURE).16 Other anxiety and depression screening instruments are also available.

No one method has been shown to be most effective for rapid screening, and the physician’s comfort level or familiarity with a particular assessment tool may guide selection. One advantage of short screening instruments is that they can be incorporated into electronic health records for easy use across continuity visits. Although routine screening for these mental comorbidities takes slightly more time—especially in high-volume family practice clinics—it needs to become standard practice to protect patients’ quality of life.

Managing psychiatric conditions in COPD

Treatment for GAD and MDD in COPD is often suboptimal and may diminish a patient’s quality of life. In one study, COPD patients with a mental illness were 46% less likely than those with COPD alone to receive medications such as short- or long-acting bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids.17 Therapy for both the physiologic abnormalities and mental disturbances should be initiated promptly to maintain an acceptable state of health.

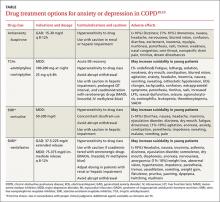

Pharmacotherapy. Reluctance to give traditional psychiatric medications to COPD patients contributes to the under-treatment of mental comorbidities. While benzodiazepines are generally not recommended—especially in severe COPD cases due to their sedative effect on respiratory drive—alternatives such as buspirone, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) have been shown to effectively reduce GAD, MDD, and dyspnea in these patients5,14(TABLE18,19).

Non-pharmacotherapy approaches. Having patients apply behavioral-modification principles to their own behavior20 has been proposed as a standard of care in the treatment of COPD.21 A recent systematic review found that self-management (behavior change) interventions in patients with COPD improved health-related quality of life, reduced hospital admissions, and helped alleviate dyspnea.22 While that review could not make clear recommendations regarding the most effective form and content of self-management in COPD,22 patient engagement and motivation in creating treatment goals are considered critical ingredients for effective self-management.21

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is an evidence-based behavioral approach designed for patients who are ambivalent about or resistant to change.23 MI works by supporting a patient’s autonomy and by activating his/her own internal motivation for change or adherence to treatment. In MI, the physician’s involvement with the patient relies on collaboration, evocation, and autonomy, rather than confrontation, education, and authority. MI involves exploration more than exhortation, and support rather than persuasion or argument. The overall goal of MI is to increase intrinsic motivation so that change arises from within and serves the patient’s goals and values.23

Benzo, et al, provide a very detailed description of a self-management process that includes MI.21 Their protocol proved to be feasible in severe COPD and helped increase patient engagement and commitment to self-management.21 This finding and similar evidence of MI’s effectiveness in a variety of other health conditions suggest that pharmacotherapy and cognitive-behavior therapy can be delivered in combination with an MI approach.

Self-management depends on a patient’s readiness to implement behavioral changes. Patients engaged in unhealthy behavior may be reluctant to change at a particular time, so the physician may focus efforts on such behaviors as self-monitoring or examining values that may lead to future behavior change.

For example, a patient may not want to stop smoking, but the physician’s willingness to ask about smoking in subsequent visits may catch the patient at a time when motivation has changed—eg, perhaps there is a new child in the home, prompting a recognition that smoking is now inconsistent with one’s values and can be resolved with smoking cessation. Awareness of an individual’s baseline behavior and readiness to change assists physicians and other health professionals in tailoring interventions for the most favorable outcome.

Several other non-pharmacologic methods to reduce symptoms of GAD and MDD in patients with COPD have been studied and supported by the literature.

- Progressive muscle relaxation, stress management, biofeedback, and guided imagery have been shown to decrease symptoms of anxiety, dyspnea, and airway obstruction.5,14

- Pulmonary rehabilitation programs including psychotherapy sessions have also relieved symptoms of GAD and MDD for patients with COPD.

- Programs that include physiotherapy, physical exercise (arm and leg exercise, aerobic conditioning, flexibility training), patient education, and psychotherapy sessions have significantly lowered GAD and MDD scores when compared with similar rehabilitation programs not offering psychotherapy.24

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy has been variably effective in treating comorbid GAD and MDD, with studies citing either superiority5 or equivalence25 to COPD education alone.

Increasingly, psychologists have been integrated into primary care with implementation of the Patient-Centered Medical Home.26 However, if primary care physicians do not have behavioral specialists available, they can contact the American Psychological Association, their state psychological association, or professional organizations, such as the Society of Behavioral Medicine, for referral to professionals trained in behavioral self-management skills.

Initiation of treatment, whether pharmacological or non-pharmacological, and emphasis on self-management of the disease can greatly improve patients' perceptions of their condition and overall quality of life.

CASE › The patient screens positive for GAD and you give him a prescription for venlafaxine to begin immediately. Using an MI approach, you help the patient clarify that being more engaged with his family is important to him. Acknowledging that your recommendations are consistent with his values, the patient agrees to pursue pulmonary rehabilitation and, with the aid of a behavioral health specialist, learn self-management techniques for medication adherence and social reengagement.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ms. Sydney Marsh, 3009 S 35th Ave., Omaha, NE 68105; sydneymarsh@creighton.edu.

1. Yohannes AM, Willgoss TG, Baldwin RC, et al. Depression and anxiety in chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, relevance, clinical implications and management principles. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25:1209-1221.

2. Punturieri A, Croxton TL, Weinmann G, et al. The changing face of COPD. Am Fam Physician. 2007;1:315-316.

3. Willgoss TG, Yohannes AM. Anxiety disorders in patients with COPD: a systematic review. Respir Care. 2013;58:858-866.

4. Porthirat C, Chaiwong W, Phetsuk N, et al. Major affective disorders in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease compared with other chronic respiratory diseases. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1583-1590.

5. Brenes GA. Anxiety and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, impact, and treatment. Psychosom Med. 2003; 65:963-970.

6. Singh G, Zhang W, Kuo YF, et al. Association of psychological disorders with 30-day readmission rates in patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Chest. 2015;Jul 23:[Epub ahead of print].

7. Vögele C, von Leupoldt A. Mental disorders in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2008;102:764-773.

8. Aydin IO, Ulusahin A. Depression, anxiety comorbidity, and disability in tuberculosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: applicability of GHQ-12. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23:77-83.

9. Dalal AA, Shah M, Lunacsek O, et al. Clinical and economic burden of depression/anxiety in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients within a managed care population. COPD. 2011;8:293-299.

10. Janssen DJA, Wouters EFM, Spruit MA. Psychosocial consequences of living with breathlessness due to advanced disease. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2015;9:232-237.

11. Atlantis E, Fahey P, Cochrane B, et al. Bidirectional associations between clinically relevant depression or anxiety and COPD. Chest. 2013;144:766-777.

12. Esser RW, Stoeckel MC, Kirsten A, et al. Structural brain changes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest. 2015;Jul 23:[Epub ahead of print].

13. Ng TP, Niti M, Tan WC, et al. Depressive symptoms and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effect on mortality, hospital readmission, symptom burden, functional status, and quality of life. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:60-67.

14. Kim HF, Kunik ME, Molinari VA, et al. Functional impairment in COPD patients. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:465-471.

15. Cleland JA, Lee AJ, Hall S. Associations of depression and anxiety with gender, age, health-related quality of life and symptoms in primary care COPD patients. Fam Pract. 2007;24:217-223.

16. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB et al. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:345-359.

17. Ajmera M, Sambamoorthi U, Metzger A, et al. Multimorbidity and COPD medication receipt among Medicaid beneficiaries with newly diagnosed COPD. Respir Care. 2015;60:1592-1602.

18. Medscape. Psychiatrics. Available at: http://reference.medscape.com/drugs/psychiatrics. Accessed March 1, 2016.

19. Physicians’ Desk Reference. Available at: http://www.pdr.net. Accessed March 1, 2016.

20. Kazdin AE. Behavior Modification in Applied Settings. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning; 2001.

21. Benzo R, Vickers K, Ernst D, et al. Development and feasibility of a self-management intervention for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease delivered with motivational interviewing strategies. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2013;33:113-123.

22. Zwerink M, Brusse-Keizer M, van der Valk PD, et al. Self management for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database System Rev. 2014;(3):CD002990.

23. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013.

24. de Godoy DV, de Godoy RF. A randomized controlled trial of the effect of psychotherapy on anxiety and depression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:1154-1157.

25. Kunik ME, Veazey C, Cully JA, et al. COPD education and cognitive behavioral therapy group treatment for clinically significant symptoms of depression and anxiety in COPD patients: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2008;38:385-396.

26. McDaniel SH, Fogarty CT. What primary care psychology has to offer the patient-centered medical home. Prof Psych Res Pract. 2009;40:483-492.

› Initiate both pharmacologic and psychological therapies for anxiety or depression coexisting with COPD to improve patient outcomes. B

› Consider buspirone as an alternative to benzodiazepines for anxiety coexistent with COPD. B

› Consider motivational interviewing as a behavioral approach to help patients who are ambivalent about or resistant to change. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › A 66-year-old man you have seen many times for issues related to his chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) comes in to your clinic for a routine visit. He has been taking budesonide/formoterol twice a day for the last 3 years; however, he has not always been compliant with his medications and has been hospitalized within the last 6 months for disease exacerbations. Today, he says he has difficulty falling asleep and often becomes short of breath, even when physically inactive. His wife, who is accompanying him today, tells you he has become increasingly distant over the past few months and is not as engaged at family outings, which he attributes to labored breathing. They’re both concerned about this change and ask for advice.

Despite the increased awareness that generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) are common comorbidities of COPD, they remain underdiagnosed and undertreated in patients with COPD. The results are increased rates of symptom exacerbation and rehospitalization.1 Family physicians, who are the primary caregivers for most patients with the disease,2 can maximize patients’ quality of life by recognizing comorbid mental illness, motivating and engaging patients in their disease management, and initiating appropriate treatment.

Anxiety and depression in COPD: A 2-way street

Several studies have assessed the prevalence of psychological disorders in patients with COPD. Affective disorders, mainly GAD and MDD, are the ones most commonly associated with poor COPD prognoses.3,4 GAD is at least 3 times more prevalent in patients with COPD than in the general US population,5 reaching upwards of 55%.1,6 Prevalence of MDD is also high, affecting approximately 40% of patients with the disease.1

GAD and MDD are more prevalent as comorbidities of COPD than they are with other chronic diseases such as orthopedic conditions, pulmonary tuberculosis, hypertension and heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and cancer.5,7-9 Patients with COPD, more so than patients with other serious chronic diseases, report heightened edginess, anxiousness, tiredness, distractibility, and irritability,5 perhaps owing in part to breathlessness and “air hunger.”10

The connection between COPD and GAD or MDD is not unidirectional, with progression of lung disease exacerbating its psychological comorbidities. The interaction is reciprocal, as clarified by Atlantis, et al, in a 2013 systematic review and meta-analysis that assessed key variables in the development of COPD and GAD or MDD.11

COPD increases the risk of MDD, which is associated with increased tobacco consumption, poor adherence with COPD medications, and decreased physical activity.11 Compounding the problem of inactivity is the fact that COPD—particularly longstanding disease—can lead to volume reductions in the anterior cingulate cortex of patients, which correlates with a persistent fear of performing physical activity.12 MDD in the setting of COPD also complicates the already complex interplay between nicotine dependence and attempts at smoking cessation.11

GAD/MDD worsens COPD outcomes

Comorbid GAD and MDD increase demands on our health care system and decrease the quality of life for patients with COPD. Anxious or depressed patients have higher 30-day readmission rates and less frequent outpatient follow-up than COPD patients without these mental comorbidities.6 Patients with comorbidities tend to have a higher prevalence of systemic symptoms independent of COPD severity,7 exhibit poorer physical and social functioning,13 and experience greater impairment of quality of life than patients with lung dysfunction alone.1,14 Patients with GAD or MDD have a 43% increased risk of any adverse COPD outcome, which can include exacerbations, COPD-related diagnoses (eg, emphysema), new anxiety or depression events, and death.11 Specifically, the risk of a COPD exacerbation rises by 31% in patients with comorbid GAD or MDD, and risk of death in those with comorbid MDD increases by 83%.11

GAD or MDD with COPD increases health care utilization and costs per patient when compared with patients who have COPD alone.9 Annual physician visits, emergency-room visits, and hospitalizations for any cause are higher in anxious or depressed COPD patients, and they have a 77% increased chance annually of a COPD-related hospitalization.9 Annual COPD-related health care costs for patients with GAD or MDD are significantly higher than the average COPD-related costs for patients without depression or anxiety, leading to significantly increased all-cause health care costs: $28,961 vs $22,512.9 Addressing and managing comorbid GAD or MDD in COPD patients could substantially reduce health care costs.

Be vigilant for anxiety, depression—even when COPD is mild

One reason comorbid GAD or MDD may be overlooked and underdiagnosed is that the symptoms can overlap those of COPD. In cases where suspicion of GAD or MDD is warranted, providers must keep separate the diagnostic inquiries for COPD and these comorbidities.6

Somatic symptoms of anxiety, such as hyperventilation, shortness of breath, and sweating, may easily be attributed to pulmonary disease instead of a psychological disorder. Differentiating the 2 processes becomes more difficult with patients younger than 60 years, as they are more likely to experience symptoms of GAD or MDD than older patients, regardless of COPD severity.15 Therefore, when assessing COPD patients, physicians need to be more vigilant for anxiety and depression, even in the mildest cases.14

Several methods exist for assessing anxiety and depression, including the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener 7 (GAD-7) and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) 2 or 9.16 All PHQ and GAD-7 screeners and translations are downloadable from www.phqscreeners.com/select-screener and permission is not required to reproduce, translate, display, or distribute them (FIGURE).16 Other anxiety and depression screening instruments are also available.

No one method has been shown to be most effective for rapid screening, and the physician’s comfort level or familiarity with a particular assessment tool may guide selection. One advantage of short screening instruments is that they can be incorporated into electronic health records for easy use across continuity visits. Although routine screening for these mental comorbidities takes slightly more time—especially in high-volume family practice clinics—it needs to become standard practice to protect patients’ quality of life.

Managing psychiatric conditions in COPD

Treatment for GAD and MDD in COPD is often suboptimal and may diminish a patient’s quality of life. In one study, COPD patients with a mental illness were 46% less likely than those with COPD alone to receive medications such as short- or long-acting bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids.17 Therapy for both the physiologic abnormalities and mental disturbances should be initiated promptly to maintain an acceptable state of health.

Pharmacotherapy. Reluctance to give traditional psychiatric medications to COPD patients contributes to the under-treatment of mental comorbidities. While benzodiazepines are generally not recommended—especially in severe COPD cases due to their sedative effect on respiratory drive—alternatives such as buspirone, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) have been shown to effectively reduce GAD, MDD, and dyspnea in these patients5,14(TABLE18,19).

Non-pharmacotherapy approaches. Having patients apply behavioral-modification principles to their own behavior20 has been proposed as a standard of care in the treatment of COPD.21 A recent systematic review found that self-management (behavior change) interventions in patients with COPD improved health-related quality of life, reduced hospital admissions, and helped alleviate dyspnea.22 While that review could not make clear recommendations regarding the most effective form and content of self-management in COPD,22 patient engagement and motivation in creating treatment goals are considered critical ingredients for effective self-management.21

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is an evidence-based behavioral approach designed for patients who are ambivalent about or resistant to change.23 MI works by supporting a patient’s autonomy and by activating his/her own internal motivation for change or adherence to treatment. In MI, the physician’s involvement with the patient relies on collaboration, evocation, and autonomy, rather than confrontation, education, and authority. MI involves exploration more than exhortation, and support rather than persuasion or argument. The overall goal of MI is to increase intrinsic motivation so that change arises from within and serves the patient’s goals and values.23

Benzo, et al, provide a very detailed description of a self-management process that includes MI.21 Their protocol proved to be feasible in severe COPD and helped increase patient engagement and commitment to self-management.21 This finding and similar evidence of MI’s effectiveness in a variety of other health conditions suggest that pharmacotherapy and cognitive-behavior therapy can be delivered in combination with an MI approach.

Self-management depends on a patient’s readiness to implement behavioral changes. Patients engaged in unhealthy behavior may be reluctant to change at a particular time, so the physician may focus efforts on such behaviors as self-monitoring or examining values that may lead to future behavior change.

For example, a patient may not want to stop smoking, but the physician’s willingness to ask about smoking in subsequent visits may catch the patient at a time when motivation has changed—eg, perhaps there is a new child in the home, prompting a recognition that smoking is now inconsistent with one’s values and can be resolved with smoking cessation. Awareness of an individual’s baseline behavior and readiness to change assists physicians and other health professionals in tailoring interventions for the most favorable outcome.

Several other non-pharmacologic methods to reduce symptoms of GAD and MDD in patients with COPD have been studied and supported by the literature.

- Progressive muscle relaxation, stress management, biofeedback, and guided imagery have been shown to decrease symptoms of anxiety, dyspnea, and airway obstruction.5,14

- Pulmonary rehabilitation programs including psychotherapy sessions have also relieved symptoms of GAD and MDD for patients with COPD.

- Programs that include physiotherapy, physical exercise (arm and leg exercise, aerobic conditioning, flexibility training), patient education, and psychotherapy sessions have significantly lowered GAD and MDD scores when compared with similar rehabilitation programs not offering psychotherapy.24

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy has been variably effective in treating comorbid GAD and MDD, with studies citing either superiority5 or equivalence25 to COPD education alone.

Increasingly, psychologists have been integrated into primary care with implementation of the Patient-Centered Medical Home.26 However, if primary care physicians do not have behavioral specialists available, they can contact the American Psychological Association, their state psychological association, or professional organizations, such as the Society of Behavioral Medicine, for referral to professionals trained in behavioral self-management skills.

Initiation of treatment, whether pharmacological or non-pharmacological, and emphasis on self-management of the disease can greatly improve patients' perceptions of their condition and overall quality of life.

CASE › The patient screens positive for GAD and you give him a prescription for venlafaxine to begin immediately. Using an MI approach, you help the patient clarify that being more engaged with his family is important to him. Acknowledging that your recommendations are consistent with his values, the patient agrees to pursue pulmonary rehabilitation and, with the aid of a behavioral health specialist, learn self-management techniques for medication adherence and social reengagement.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ms. Sydney Marsh, 3009 S 35th Ave., Omaha, NE 68105; sydneymarsh@creighton.edu.

› Initiate both pharmacologic and psychological therapies for anxiety or depression coexisting with COPD to improve patient outcomes. B

› Consider buspirone as an alternative to benzodiazepines for anxiety coexistent with COPD. B

› Consider motivational interviewing as a behavioral approach to help patients who are ambivalent about or resistant to change. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › A 66-year-old man you have seen many times for issues related to his chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) comes in to your clinic for a routine visit. He has been taking budesonide/formoterol twice a day for the last 3 years; however, he has not always been compliant with his medications and has been hospitalized within the last 6 months for disease exacerbations. Today, he says he has difficulty falling asleep and often becomes short of breath, even when physically inactive. His wife, who is accompanying him today, tells you he has become increasingly distant over the past few months and is not as engaged at family outings, which he attributes to labored breathing. They’re both concerned about this change and ask for advice.

Despite the increased awareness that generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) are common comorbidities of COPD, they remain underdiagnosed and undertreated in patients with COPD. The results are increased rates of symptom exacerbation and rehospitalization.1 Family physicians, who are the primary caregivers for most patients with the disease,2 can maximize patients’ quality of life by recognizing comorbid mental illness, motivating and engaging patients in their disease management, and initiating appropriate treatment.

Anxiety and depression in COPD: A 2-way street

Several studies have assessed the prevalence of psychological disorders in patients with COPD. Affective disorders, mainly GAD and MDD, are the ones most commonly associated with poor COPD prognoses.3,4 GAD is at least 3 times more prevalent in patients with COPD than in the general US population,5 reaching upwards of 55%.1,6 Prevalence of MDD is also high, affecting approximately 40% of patients with the disease.1

GAD and MDD are more prevalent as comorbidities of COPD than they are with other chronic diseases such as orthopedic conditions, pulmonary tuberculosis, hypertension and heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and cancer.5,7-9 Patients with COPD, more so than patients with other serious chronic diseases, report heightened edginess, anxiousness, tiredness, distractibility, and irritability,5 perhaps owing in part to breathlessness and “air hunger.”10

The connection between COPD and GAD or MDD is not unidirectional, with progression of lung disease exacerbating its psychological comorbidities. The interaction is reciprocal, as clarified by Atlantis, et al, in a 2013 systematic review and meta-analysis that assessed key variables in the development of COPD and GAD or MDD.11

COPD increases the risk of MDD, which is associated with increased tobacco consumption, poor adherence with COPD medications, and decreased physical activity.11 Compounding the problem of inactivity is the fact that COPD—particularly longstanding disease—can lead to volume reductions in the anterior cingulate cortex of patients, which correlates with a persistent fear of performing physical activity.12 MDD in the setting of COPD also complicates the already complex interplay between nicotine dependence and attempts at smoking cessation.11

GAD/MDD worsens COPD outcomes

Comorbid GAD and MDD increase demands on our health care system and decrease the quality of life for patients with COPD. Anxious or depressed patients have higher 30-day readmission rates and less frequent outpatient follow-up than COPD patients without these mental comorbidities.6 Patients with comorbidities tend to have a higher prevalence of systemic symptoms independent of COPD severity,7 exhibit poorer physical and social functioning,13 and experience greater impairment of quality of life than patients with lung dysfunction alone.1,14 Patients with GAD or MDD have a 43% increased risk of any adverse COPD outcome, which can include exacerbations, COPD-related diagnoses (eg, emphysema), new anxiety or depression events, and death.11 Specifically, the risk of a COPD exacerbation rises by 31% in patients with comorbid GAD or MDD, and risk of death in those with comorbid MDD increases by 83%.11

GAD or MDD with COPD increases health care utilization and costs per patient when compared with patients who have COPD alone.9 Annual physician visits, emergency-room visits, and hospitalizations for any cause are higher in anxious or depressed COPD patients, and they have a 77% increased chance annually of a COPD-related hospitalization.9 Annual COPD-related health care costs for patients with GAD or MDD are significantly higher than the average COPD-related costs for patients without depression or anxiety, leading to significantly increased all-cause health care costs: $28,961 vs $22,512.9 Addressing and managing comorbid GAD or MDD in COPD patients could substantially reduce health care costs.

Be vigilant for anxiety, depression—even when COPD is mild

One reason comorbid GAD or MDD may be overlooked and underdiagnosed is that the symptoms can overlap those of COPD. In cases where suspicion of GAD or MDD is warranted, providers must keep separate the diagnostic inquiries for COPD and these comorbidities.6

Somatic symptoms of anxiety, such as hyperventilation, shortness of breath, and sweating, may easily be attributed to pulmonary disease instead of a psychological disorder. Differentiating the 2 processes becomes more difficult with patients younger than 60 years, as they are more likely to experience symptoms of GAD or MDD than older patients, regardless of COPD severity.15 Therefore, when assessing COPD patients, physicians need to be more vigilant for anxiety and depression, even in the mildest cases.14

Several methods exist for assessing anxiety and depression, including the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener 7 (GAD-7) and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) 2 or 9.16 All PHQ and GAD-7 screeners and translations are downloadable from www.phqscreeners.com/select-screener and permission is not required to reproduce, translate, display, or distribute them (FIGURE).16 Other anxiety and depression screening instruments are also available.

No one method has been shown to be most effective for rapid screening, and the physician’s comfort level or familiarity with a particular assessment tool may guide selection. One advantage of short screening instruments is that they can be incorporated into electronic health records for easy use across continuity visits. Although routine screening for these mental comorbidities takes slightly more time—especially in high-volume family practice clinics—it needs to become standard practice to protect patients’ quality of life.

Managing psychiatric conditions in COPD

Treatment for GAD and MDD in COPD is often suboptimal and may diminish a patient’s quality of life. In one study, COPD patients with a mental illness were 46% less likely than those with COPD alone to receive medications such as short- or long-acting bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids.17 Therapy for both the physiologic abnormalities and mental disturbances should be initiated promptly to maintain an acceptable state of health.

Pharmacotherapy. Reluctance to give traditional psychiatric medications to COPD patients contributes to the under-treatment of mental comorbidities. While benzodiazepines are generally not recommended—especially in severe COPD cases due to their sedative effect on respiratory drive—alternatives such as buspirone, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) have been shown to effectively reduce GAD, MDD, and dyspnea in these patients5,14(TABLE18,19).

Non-pharmacotherapy approaches. Having patients apply behavioral-modification principles to their own behavior20 has been proposed as a standard of care in the treatment of COPD.21 A recent systematic review found that self-management (behavior change) interventions in patients with COPD improved health-related quality of life, reduced hospital admissions, and helped alleviate dyspnea.22 While that review could not make clear recommendations regarding the most effective form and content of self-management in COPD,22 patient engagement and motivation in creating treatment goals are considered critical ingredients for effective self-management.21

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is an evidence-based behavioral approach designed for patients who are ambivalent about or resistant to change.23 MI works by supporting a patient’s autonomy and by activating his/her own internal motivation for change or adherence to treatment. In MI, the physician’s involvement with the patient relies on collaboration, evocation, and autonomy, rather than confrontation, education, and authority. MI involves exploration more than exhortation, and support rather than persuasion or argument. The overall goal of MI is to increase intrinsic motivation so that change arises from within and serves the patient’s goals and values.23

Benzo, et al, provide a very detailed description of a self-management process that includes MI.21 Their protocol proved to be feasible in severe COPD and helped increase patient engagement and commitment to self-management.21 This finding and similar evidence of MI’s effectiveness in a variety of other health conditions suggest that pharmacotherapy and cognitive-behavior therapy can be delivered in combination with an MI approach.

Self-management depends on a patient’s readiness to implement behavioral changes. Patients engaged in unhealthy behavior may be reluctant to change at a particular time, so the physician may focus efforts on such behaviors as self-monitoring or examining values that may lead to future behavior change.

For example, a patient may not want to stop smoking, but the physician’s willingness to ask about smoking in subsequent visits may catch the patient at a time when motivation has changed—eg, perhaps there is a new child in the home, prompting a recognition that smoking is now inconsistent with one’s values and can be resolved with smoking cessation. Awareness of an individual’s baseline behavior and readiness to change assists physicians and other health professionals in tailoring interventions for the most favorable outcome.

Several other non-pharmacologic methods to reduce symptoms of GAD and MDD in patients with COPD have been studied and supported by the literature.

- Progressive muscle relaxation, stress management, biofeedback, and guided imagery have been shown to decrease symptoms of anxiety, dyspnea, and airway obstruction.5,14

- Pulmonary rehabilitation programs including psychotherapy sessions have also relieved symptoms of GAD and MDD for patients with COPD.

- Programs that include physiotherapy, physical exercise (arm and leg exercise, aerobic conditioning, flexibility training), patient education, and psychotherapy sessions have significantly lowered GAD and MDD scores when compared with similar rehabilitation programs not offering psychotherapy.24

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy has been variably effective in treating comorbid GAD and MDD, with studies citing either superiority5 or equivalence25 to COPD education alone.

Increasingly, psychologists have been integrated into primary care with implementation of the Patient-Centered Medical Home.26 However, if primary care physicians do not have behavioral specialists available, they can contact the American Psychological Association, their state psychological association, or professional organizations, such as the Society of Behavioral Medicine, for referral to professionals trained in behavioral self-management skills.

Initiation of treatment, whether pharmacological or non-pharmacological, and emphasis on self-management of the disease can greatly improve patients' perceptions of their condition and overall quality of life.

CASE › The patient screens positive for GAD and you give him a prescription for venlafaxine to begin immediately. Using an MI approach, you help the patient clarify that being more engaged with his family is important to him. Acknowledging that your recommendations are consistent with his values, the patient agrees to pursue pulmonary rehabilitation and, with the aid of a behavioral health specialist, learn self-management techniques for medication adherence and social reengagement.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ms. Sydney Marsh, 3009 S 35th Ave., Omaha, NE 68105; sydneymarsh@creighton.edu.

1. Yohannes AM, Willgoss TG, Baldwin RC, et al. Depression and anxiety in chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, relevance, clinical implications and management principles. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25:1209-1221.

2. Punturieri A, Croxton TL, Weinmann G, et al. The changing face of COPD. Am Fam Physician. 2007;1:315-316.

3. Willgoss TG, Yohannes AM. Anxiety disorders in patients with COPD: a systematic review. Respir Care. 2013;58:858-866.

4. Porthirat C, Chaiwong W, Phetsuk N, et al. Major affective disorders in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease compared with other chronic respiratory diseases. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1583-1590.

5. Brenes GA. Anxiety and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, impact, and treatment. Psychosom Med. 2003; 65:963-970.

6. Singh G, Zhang W, Kuo YF, et al. Association of psychological disorders with 30-day readmission rates in patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Chest. 2015;Jul 23:[Epub ahead of print].

7. Vögele C, von Leupoldt A. Mental disorders in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2008;102:764-773.

8. Aydin IO, Ulusahin A. Depression, anxiety comorbidity, and disability in tuberculosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: applicability of GHQ-12. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23:77-83.

9. Dalal AA, Shah M, Lunacsek O, et al. Clinical and economic burden of depression/anxiety in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients within a managed care population. COPD. 2011;8:293-299.

10. Janssen DJA, Wouters EFM, Spruit MA. Psychosocial consequences of living with breathlessness due to advanced disease. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2015;9:232-237.

11. Atlantis E, Fahey P, Cochrane B, et al. Bidirectional associations between clinically relevant depression or anxiety and COPD. Chest. 2013;144:766-777.

12. Esser RW, Stoeckel MC, Kirsten A, et al. Structural brain changes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest. 2015;Jul 23:[Epub ahead of print].

13. Ng TP, Niti M, Tan WC, et al. Depressive symptoms and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effect on mortality, hospital readmission, symptom burden, functional status, and quality of life. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:60-67.

14. Kim HF, Kunik ME, Molinari VA, et al. Functional impairment in COPD patients. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:465-471.

15. Cleland JA, Lee AJ, Hall S. Associations of depression and anxiety with gender, age, health-related quality of life and symptoms in primary care COPD patients. Fam Pract. 2007;24:217-223.

16. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB et al. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:345-359.

17. Ajmera M, Sambamoorthi U, Metzger A, et al. Multimorbidity and COPD medication receipt among Medicaid beneficiaries with newly diagnosed COPD. Respir Care. 2015;60:1592-1602.

18. Medscape. Psychiatrics. Available at: http://reference.medscape.com/drugs/psychiatrics. Accessed March 1, 2016.

19. Physicians’ Desk Reference. Available at: http://www.pdr.net. Accessed March 1, 2016.

20. Kazdin AE. Behavior Modification in Applied Settings. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning; 2001.

21. Benzo R, Vickers K, Ernst D, et al. Development and feasibility of a self-management intervention for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease delivered with motivational interviewing strategies. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2013;33:113-123.

22. Zwerink M, Brusse-Keizer M, van der Valk PD, et al. Self management for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database System Rev. 2014;(3):CD002990.

23. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013.

24. de Godoy DV, de Godoy RF. A randomized controlled trial of the effect of psychotherapy on anxiety and depression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:1154-1157.

25. Kunik ME, Veazey C, Cully JA, et al. COPD education and cognitive behavioral therapy group treatment for clinically significant symptoms of depression and anxiety in COPD patients: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2008;38:385-396.

26. McDaniel SH, Fogarty CT. What primary care psychology has to offer the patient-centered medical home. Prof Psych Res Pract. 2009;40:483-492.

1. Yohannes AM, Willgoss TG, Baldwin RC, et al. Depression and anxiety in chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, relevance, clinical implications and management principles. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25:1209-1221.

2. Punturieri A, Croxton TL, Weinmann G, et al. The changing face of COPD. Am Fam Physician. 2007;1:315-316.

3. Willgoss TG, Yohannes AM. Anxiety disorders in patients with COPD: a systematic review. Respir Care. 2013;58:858-866.

4. Porthirat C, Chaiwong W, Phetsuk N, et al. Major affective disorders in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease compared with other chronic respiratory diseases. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1583-1590.

5. Brenes GA. Anxiety and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, impact, and treatment. Psychosom Med. 2003; 65:963-970.

6. Singh G, Zhang W, Kuo YF, et al. Association of psychological disorders with 30-day readmission rates in patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Chest. 2015;Jul 23:[Epub ahead of print].

7. Vögele C, von Leupoldt A. Mental disorders in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2008;102:764-773.

8. Aydin IO, Ulusahin A. Depression, anxiety comorbidity, and disability in tuberculosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: applicability of GHQ-12. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23:77-83.

9. Dalal AA, Shah M, Lunacsek O, et al. Clinical and economic burden of depression/anxiety in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients within a managed care population. COPD. 2011;8:293-299.

10. Janssen DJA, Wouters EFM, Spruit MA. Psychosocial consequences of living with breathlessness due to advanced disease. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2015;9:232-237.

11. Atlantis E, Fahey P, Cochrane B, et al. Bidirectional associations between clinically relevant depression or anxiety and COPD. Chest. 2013;144:766-777.

12. Esser RW, Stoeckel MC, Kirsten A, et al. Structural brain changes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest. 2015;Jul 23:[Epub ahead of print].

13. Ng TP, Niti M, Tan WC, et al. Depressive symptoms and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effect on mortality, hospital readmission, symptom burden, functional status, and quality of life. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:60-67.

14. Kim HF, Kunik ME, Molinari VA, et al. Functional impairment in COPD patients. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:465-471.

15. Cleland JA, Lee AJ, Hall S. Associations of depression and anxiety with gender, age, health-related quality of life and symptoms in primary care COPD patients. Fam Pract. 2007;24:217-223.

16. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB et al. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:345-359.

17. Ajmera M, Sambamoorthi U, Metzger A, et al. Multimorbidity and COPD medication receipt among Medicaid beneficiaries with newly diagnosed COPD. Respir Care. 2015;60:1592-1602.

18. Medscape. Psychiatrics. Available at: http://reference.medscape.com/drugs/psychiatrics. Accessed March 1, 2016.

19. Physicians’ Desk Reference. Available at: http://www.pdr.net. Accessed March 1, 2016.

20. Kazdin AE. Behavior Modification in Applied Settings. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning; 2001.

21. Benzo R, Vickers K, Ernst D, et al. Development and feasibility of a self-management intervention for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease delivered with motivational interviewing strategies. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2013;33:113-123.

22. Zwerink M, Brusse-Keizer M, van der Valk PD, et al. Self management for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database System Rev. 2014;(3):CD002990.

23. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013.

24. de Godoy DV, de Godoy RF. A randomized controlled trial of the effect of psychotherapy on anxiety and depression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:1154-1157.

25. Kunik ME, Veazey C, Cully JA, et al. COPD education and cognitive behavioral therapy group treatment for clinically significant symptoms of depression and anxiety in COPD patients: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2008;38:385-396.

26. McDaniel SH, Fogarty CT. What primary care psychology has to offer the patient-centered medical home. Prof Psych Res Pract. 2009;40:483-492.