User login

Dialing back opioids for chronic pain one conversation at a time

ABSTRACT

Purpose Our study examined the efficacy of a primary-care intervention in reducing opioid use among patients who have chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP). We also recorded the intervention’s effect on patients’ decisions to leave (or stay) with the primary-care practice.

Methods A family physician (FP) identified 41 patients in his practice who had CNCP of at least 6 month’s duration and were using opioids. The intervention with each patient involved an initial discussion of ethical principles, evidence-based practice, and current published guidelines. Following the discussion, patients self-selected to participate with their FP in a continuing tapering program or to accept referral to a pain center for management of their opioid medications. Tapering ranged from a 10% reduction per week to a more rapid 25% to 50% reduction every few days. Twenty-seven patients continued tapering with their FP, and 6 months later were retrospectively placed in the Taper Group. Fourteen patients chose not to pursue the tapering option and were referred to a single-modality medical pain clinic (MPC). All patients had the option of staying with the FP for other medical care.

Results At baseline and again at 6 months post-initial intervention, the MPC Group was taking significantly higher daily doses of morphine equivalents than the Taper Group. The Taper Group at 6 months was taking significantly lower average daily narcotic doses in morphine equivalents than at baseline. No significant baseline-to-6 month differences were found in the MPC Group. Contrary to many physicians’ fear of losing patients following candid discussions about opioid use, 40 of the 41 patients continued with the FP for other health needs.

Conclusions FPs can frankly discuss opioid use with their patients based on ethical principles and evidence-based recommendations and employ a tapering protocol consistent with current opioid treatment guidelines without jeopardizing the patient-physician relationship.

[polldaddy:10180698]

Opioid prescriptions for chronic noncancer pain (CNCP) have increased significantly over the past 25 years in the United States.1 Despite methodologic concerns surrounding research on opioid harms, prescription opioid misuse among CNCP patients is estimated to be 21% to 29% and prescription addiction 8% to 12%.2 Tragically, with the overall increase in opioid use for CNCP, substance-related hospital admissions and deaths due to opioid overdose have also risen.3

Increased opioid use began in 1985 when the World Health Organization expanded its ethical mandate for pain relief in dying patients to include relief from all cancer pain.3 Opioid use then accelerated following Portenoy and Foley’s 1986 article4 and the 1997 consensus statement by the American Academy of Pain Medicine (AAPM) and the American Pain Society (APS),5 with both organizations arguing that opioids have a role in the treatment of CNCP. Increased use of opioids for CNCP continued throughout the 1990s and 2000s, as many states passed legislation removing sanctions on prescribing long-term and high-dose opioid therapy, and pharmaceutical companies aggressively marketed sustained-release opioids.3

A balanced approach to opioids. While acknowledging the serious public health problems of drug abuse, addiction, and diversion of opioids from licit to illicit uses, clinical research and regulation leaders have called for a balanced approach that recognizes the legitimate medical need for opioids for CNCP. In 2009 the APS, in partnership with the AAPM, published evidence-based guidelines on chronic opioid therapy (COT) for adults with CNCP.6 In developing these guidelines, a multidisciplinary panel of experts conducted systematic reviews of available evidence and made recommendations on formulating COT for individuals, initiating and titrating therapy, regularly monitoring patients, and managing opioid-related adverse effects. Additional recommendations addressed the use of therapies focusing on psychosocial factors. The APS-AAPM guidelines received the highest rating in a systematic review critically appraising 13 guidelines that address the use of opioids for CNCP.7

Continue to: When opioid use is prolonged...

When opioid use is prolonged. Most primary care physicians are aware of the risks of prolonged opioid use, and many have successfully tapered or discontinued opioid medications for patients in acute or pre-chronic stages of pain.8 However, many physicians face the challenge of patients who have used COT for a longer time. The APS-AAPM guidelines may help primary care physicians at any stage of treating CNCP patients.

METHODS

Purpose and design. This retrospective study, which reviewed pretest-posttest findings between and within study groups, received an exempt status from Creighton University’s institutional review board. We designed the study to determine the efficacy of an intervention protocol to reduce opioid use by patients with CNCP who had been in a family physician (FP)'s panel for quite some time. Furthermore, because a common fear among primary care providers is that raising concerns with patients about their opioid use may cause those patients to leave their panel,9 our study also recorded how many patients stayed with their FP after initiation of the opioid management protocol.

Subjects. This study tracked 41 patients with CNCP in 1 FP’s panel. Inclusion criteria for participation was: 1) presence of CNCP for at least 6 months, 2) current use of opioid medication for CNCP, 3) age of at least 16 years, and 4) ability to read and write English. Two exclusion criteria were the presence of a surgically correctable condition or an organic brain syndrome or psychosis.

Clinical intervention. The FP identified eligible patients in his practice that were taking opioids for CNCP and initiated a discussion with each of them emphasizing his desire to follow the ethical principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, respect for autonomy, and justice.10 The FP also presented his reasons for wanting the patient to stop using opioid medication. They included his beliefs that:

1) COT was not safe for the patient based on a growing body of published evidence of harm and death from COT3;

2) long-term use of opioids could lead to misuse, abuse, or addiction2;

3) prolonged opioid use paradoxically increases pain sensitivity that does not resolve

4) the patient’s current pain medications were not in line with published guidelines for use of opioids for CNCP.6

Initially, 45 patients were eligible for the study, but 4 declined participation before the intervention discussion and were immediately referred to a single-modality medical pain clinic (MPC). These patients were not included in subsequent analyses. Of the remaining 41 patients, all had a discussion with the MD about ethical principles, practice guidelines, and the importance of opioid tapering. After the discussion, patients decided whether to continue with the plan to taper their opioid therapy or to not taper their therapy and so receive a referral to an MPC.

Continue to: The 27 patients who chose to work with...

The 27 patients who chose to work with their FP started an individually tailored opioid-tapering program and were retrospectively placed in the Taper Group 6 months later. Tapering ranged from a slow 10% reduction in dosage per week to a more rapid 25% to 50% reduction every few days. Although evidence to guide specific recommendations on the rate of reduction is lacking, a slower rate may reduce unpleasant symptoms of opioid withdrawal.6 Following the patient-FP discussion, the 14 patients who chose not to pursue the tapering option were referred to an MPC for pain management, but could opt to remain with the FP for all other medical care. At 6 months post-discussion, we retrospectively assigned these 14 patients to the MPC Group.

Measures. We obtained demographic and medical information, including age, gender, race, marital status, and medication level in morphine equivalents, from the electronic health record. Medication level in morphine equivalents was recorded at the beginning of the intervention and again 6 months later. All analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 24 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) with P<.05 used to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Between-group differences. The Taper and MPC groups did not differ significantly on demographic variables, with mean ages, respectively, at 57 and 51 years, sex 56% and 50% female, race 74% and 79% white, and marital status 48% and 50% married.

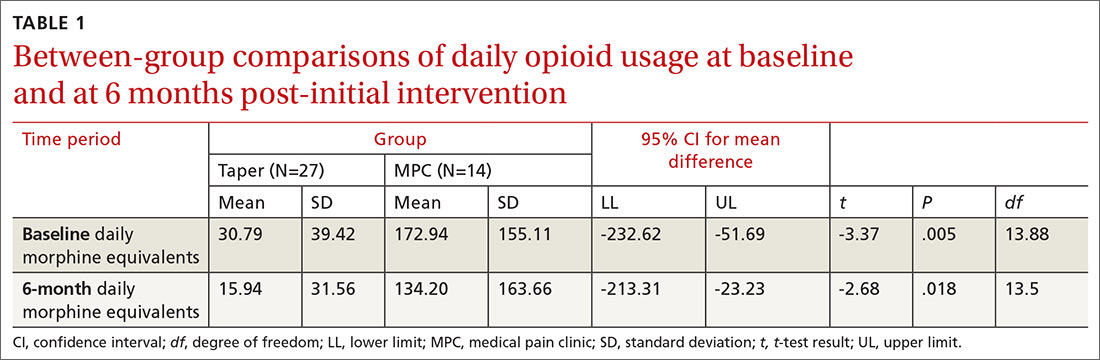

We found significant differences between the Taper and MPC groups on total daily dose in morphine equivalents at baseline and at 6 months following initial intervention. The Levene’s test for equality of variances was statistically significant, indicating unequal variances between the groups. In our SPSS analyses, we therefore used the option “equal variances not assumed.” TABLE 1 lists resultant means, standard deviations, individual sample t-test scores, and confidence intervals. The MPC Group was taking significantly higher daily doses of morphine equivalents than the Taper Group both at baseline and at 6 months following initial intervention.

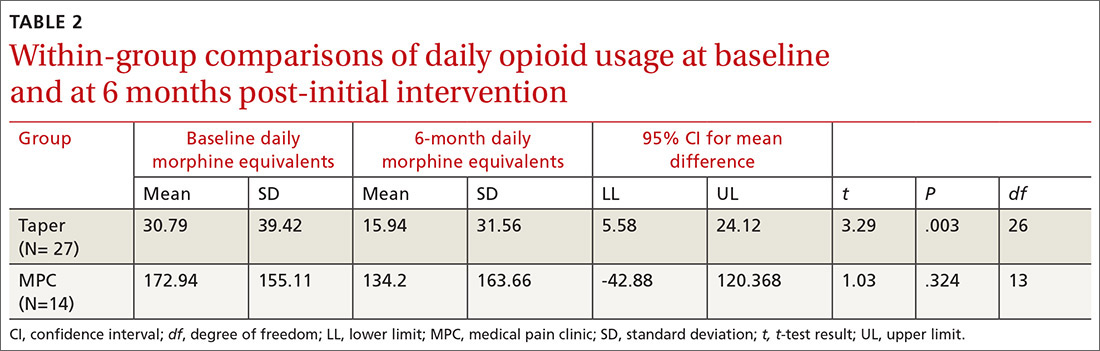

Within-group differences. Paired sample t tests indicated significant differences between baseline and 6-month average daily narcotic doses in morphine equivalents for the Taper Group. No significant difference was found between baseline and 6-month daily morphine equivalents for the MPC group. These results indicated that patients who continued opioid tapering with the FP significantly reduced their daily morphine equivalents over the 6 months of the study. Patients in the MPC Group reduced morphine equivalents over the 6 months, but the reduction was not statistically significant. Paired sample t test results are presented in TABLE 2.

Continue to: Patient retention

Patient retention. All but one of the 41 patients in the Tapering and MPC groups continued with the FP for the remainder of their health care needs. Contrary to some physicians’ fears, the patients in this study maintained continuity with their FP.

DISCUSSION

Results of this study indicate that an intervention consisting of a physician-patient discussion of ethical principles and evidence-based practice, followed by individualized opioid tapering per published guidelines, led to a significant reduction in opioid use in patients with CNCP. The Taper Group, which completed the intervention, exhibited significant morphine reductions between baseline and 6-month follow-up. This did not hold true for the MPC Group.

The MPC Group, despite participating in the discussion with the FP, chose not to complete the tapering program and was referred to a single-modality MPC where opioids were managed rather than tapered. While the MPC group reduced daily opioid dose levels, the reduction was not statistically significant. A possible reason for no difference within the MPC Group may be that they had greater dependence on opioids, as their baseline average daily dose was much higher than that in the Taper Group (173 mg vs 31 mg, respectively). Although we did not assess anxiety directly, we speculate that the MPC Group was more anxious about opioid reduction than the Taper Group, and that this anxiety potentially led 4 patients to opt out of the initial FP discussion and 14 patients to self-select out of the tapering program following the discussion.

The FP intervention was successful for the Taper Group. For MPC patients, an enhanced intervention including behavior health strategies13 might have reduced anxiety and increased motivation14 to continue tapering. Based on moderate-quality evidence, APS-AAPM guidelines strongly recommend that CNCP be viewed as a complex biopsychosocial condition. Therefore, clinicians who prescribe opioids should routinely integrate psychotherapeutic interventions, functional restoration, interdisciplinary therapy, and other adjunctive nonopioid therapies.6

Opioid tapering within multidisciplinary rehabilitation programs is possible without significant worsening of pain, mood, and function.15 Recently, an outpatient opioid-tapering support intervention showed promise for efficacy in reducing prescription opioid doses without resultant increases in pain intensity or pain interference.16

Continue to: The tapering protocol in our study...

The tapering protocol in our study and the inclusion of behavioral health co-interventions are also recommended by the 2016 guidelines published by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.17 More information on the similarities and differences among the various guidelines is available online.18,19

Caveats with our study. Patients’ entry into the Taper or MPC groups occurred through self-selection rather than random assignment. Thus, caution is recommended in interpreting findings of the FP intervention. And, we did not measure patients’ levels of pain, so differences between groups may have been possible. In addition, the number of patients per group was relatively small, which may have accounted for the lack of significance in the MPC Group findings. Conversely, significant reductions in opioid use in the small tapering sample suggests a relatively robust intervention, despite a lack of random assignment to treatment conditions.

These findings suggest that FPs can have a frank conversation about opioid use with their patients based on ethical principles and evidence-based practice, and employ a tapering protocol consistent with current opioid treatment guidelines. Furthermore, this approach appears not to jeopardize the patient-physician relationship.

CORRESPONDENCE

Thomas P. Guck, PhD, Creighton University School of Medicine, 2412 Cuming Street, Omaha, NE 68131; tpguck@creighton.edu.

1. Manchikanti L, Helm S, Fellows B, et al. Opioid epidemic in the United States. Pain Physician. 2012;15:ES9-ES38.

2. Vowles KE, McEntee ML, Julnes PS, et al. Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: a systematic review and data synthesis. Pain. 2015;156:569-576.

3. Sullivan MD, Howe CQ. Opioid therapy for chronic pain in the United States: promises and perils. Pain. 2013;154:S94-S100.

4. Portenoy RK, Foley KM. Chronic use of opioid analgesics in non-malignant pain: report of 38 cases. Pain. 1986;25:171-186.

5. The use of opioids for the treatment of chronic pain. A consensus statement from the American Academy of Pain Medicine and the American Pain Society. Clin J Pain. 1997;13:6-8.

6. Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain. 2009;10:113-130.

7. Nuckols TK, Anderson L, Popescu I, et al. Opioid prescribing: a systematic review and critical appraisal of guidelines for chronic pain. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:38-47.

8. Hwang CS, Turner LW, Kruszewski SP, et al. Primary care physicians’ knowledge and attitudes regarding prescription opioid abuse and diversion. Clin J Pain. 2016;279-284.

9. Top 15 challenges facing physicians in 2015. Medical Economics. http://www.medicaleconomics.com/medical-economics/news/top-15-challenges-facing-physicians-2015?page=0,12. Accessed October 18, 2018.

10. Kotalik J. Controlling pain and reducing misuse of opioids: ethical considerations. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:381-385.

11. Angst MS, Clark JD. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:570-587.

12. Wachholtz A, Gonzalez G. Co-morbid pain and opioid addiction: long term effect of opioid maintenance on acute pain. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;145:143-149.

13. Hunter CL, Goodie JL, Oordt MS, Dobmeyer AC. Integrated Behavioral Health in Primary Care. 2nd ed. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2017.

14. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013.

15. Townsend CO, Kerkvliet JL, Bruce BK, et al. A longitudinal study of the efficacy of a comprehensive pain rehabilitation program with opioid withdrawal: comparison of treatment outcomes based on opioid use status at admission. Pain. 2008;140:177-189.

16. Sullivan MD, Turner JA, DiLodovico C, et al. Prescription opioid taper support for outpatients with chronic pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain. 2017;18:308-318.

17. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain - United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-49.

18. Barth KS, Guille C, McCauley J, et al. Targeting practitioners: a review of guidelines, training, and policy in pain management. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;173:S22-S30.

19. CDC. Common Elements in Guidelines for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain. Injury Prevention & Control: Prescription Drug Overdose 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/common-elements.html. Accessed October 18, 2018.

ABSTRACT

Purpose Our study examined the efficacy of a primary-care intervention in reducing opioid use among patients who have chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP). We also recorded the intervention’s effect on patients’ decisions to leave (or stay) with the primary-care practice.

Methods A family physician (FP) identified 41 patients in his practice who had CNCP of at least 6 month’s duration and were using opioids. The intervention with each patient involved an initial discussion of ethical principles, evidence-based practice, and current published guidelines. Following the discussion, patients self-selected to participate with their FP in a continuing tapering program or to accept referral to a pain center for management of their opioid medications. Tapering ranged from a 10% reduction per week to a more rapid 25% to 50% reduction every few days. Twenty-seven patients continued tapering with their FP, and 6 months later were retrospectively placed in the Taper Group. Fourteen patients chose not to pursue the tapering option and were referred to a single-modality medical pain clinic (MPC). All patients had the option of staying with the FP for other medical care.

Results At baseline and again at 6 months post-initial intervention, the MPC Group was taking significantly higher daily doses of morphine equivalents than the Taper Group. The Taper Group at 6 months was taking significantly lower average daily narcotic doses in morphine equivalents than at baseline. No significant baseline-to-6 month differences were found in the MPC Group. Contrary to many physicians’ fear of losing patients following candid discussions about opioid use, 40 of the 41 patients continued with the FP for other health needs.

Conclusions FPs can frankly discuss opioid use with their patients based on ethical principles and evidence-based recommendations and employ a tapering protocol consistent with current opioid treatment guidelines without jeopardizing the patient-physician relationship.

[polldaddy:10180698]

Opioid prescriptions for chronic noncancer pain (CNCP) have increased significantly over the past 25 years in the United States.1 Despite methodologic concerns surrounding research on opioid harms, prescription opioid misuse among CNCP patients is estimated to be 21% to 29% and prescription addiction 8% to 12%.2 Tragically, with the overall increase in opioid use for CNCP, substance-related hospital admissions and deaths due to opioid overdose have also risen.3

Increased opioid use began in 1985 when the World Health Organization expanded its ethical mandate for pain relief in dying patients to include relief from all cancer pain.3 Opioid use then accelerated following Portenoy and Foley’s 1986 article4 and the 1997 consensus statement by the American Academy of Pain Medicine (AAPM) and the American Pain Society (APS),5 with both organizations arguing that opioids have a role in the treatment of CNCP. Increased use of opioids for CNCP continued throughout the 1990s and 2000s, as many states passed legislation removing sanctions on prescribing long-term and high-dose opioid therapy, and pharmaceutical companies aggressively marketed sustained-release opioids.3

A balanced approach to opioids. While acknowledging the serious public health problems of drug abuse, addiction, and diversion of opioids from licit to illicit uses, clinical research and regulation leaders have called for a balanced approach that recognizes the legitimate medical need for opioids for CNCP. In 2009 the APS, in partnership with the AAPM, published evidence-based guidelines on chronic opioid therapy (COT) for adults with CNCP.6 In developing these guidelines, a multidisciplinary panel of experts conducted systematic reviews of available evidence and made recommendations on formulating COT for individuals, initiating and titrating therapy, regularly monitoring patients, and managing opioid-related adverse effects. Additional recommendations addressed the use of therapies focusing on psychosocial factors. The APS-AAPM guidelines received the highest rating in a systematic review critically appraising 13 guidelines that address the use of opioids for CNCP.7

Continue to: When opioid use is prolonged...

When opioid use is prolonged. Most primary care physicians are aware of the risks of prolonged opioid use, and many have successfully tapered or discontinued opioid medications for patients in acute or pre-chronic stages of pain.8 However, many physicians face the challenge of patients who have used COT for a longer time. The APS-AAPM guidelines may help primary care physicians at any stage of treating CNCP patients.

METHODS

Purpose and design. This retrospective study, which reviewed pretest-posttest findings between and within study groups, received an exempt status from Creighton University’s institutional review board. We designed the study to determine the efficacy of an intervention protocol to reduce opioid use by patients with CNCP who had been in a family physician (FP)'s panel for quite some time. Furthermore, because a common fear among primary care providers is that raising concerns with patients about their opioid use may cause those patients to leave their panel,9 our study also recorded how many patients stayed with their FP after initiation of the opioid management protocol.

Subjects. This study tracked 41 patients with CNCP in 1 FP’s panel. Inclusion criteria for participation was: 1) presence of CNCP for at least 6 months, 2) current use of opioid medication for CNCP, 3) age of at least 16 years, and 4) ability to read and write English. Two exclusion criteria were the presence of a surgically correctable condition or an organic brain syndrome or psychosis.

Clinical intervention. The FP identified eligible patients in his practice that were taking opioids for CNCP and initiated a discussion with each of them emphasizing his desire to follow the ethical principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, respect for autonomy, and justice.10 The FP also presented his reasons for wanting the patient to stop using opioid medication. They included his beliefs that:

1) COT was not safe for the patient based on a growing body of published evidence of harm and death from COT3;

2) long-term use of opioids could lead to misuse, abuse, or addiction2;

3) prolonged opioid use paradoxically increases pain sensitivity that does not resolve

4) the patient’s current pain medications were not in line with published guidelines for use of opioids for CNCP.6

Initially, 45 patients were eligible for the study, but 4 declined participation before the intervention discussion and were immediately referred to a single-modality medical pain clinic (MPC). These patients were not included in subsequent analyses. Of the remaining 41 patients, all had a discussion with the MD about ethical principles, practice guidelines, and the importance of opioid tapering. After the discussion, patients decided whether to continue with the plan to taper their opioid therapy or to not taper their therapy and so receive a referral to an MPC.

Continue to: The 27 patients who chose to work with...

The 27 patients who chose to work with their FP started an individually tailored opioid-tapering program and were retrospectively placed in the Taper Group 6 months later. Tapering ranged from a slow 10% reduction in dosage per week to a more rapid 25% to 50% reduction every few days. Although evidence to guide specific recommendations on the rate of reduction is lacking, a slower rate may reduce unpleasant symptoms of opioid withdrawal.6 Following the patient-FP discussion, the 14 patients who chose not to pursue the tapering option were referred to an MPC for pain management, but could opt to remain with the FP for all other medical care. At 6 months post-discussion, we retrospectively assigned these 14 patients to the MPC Group.

Measures. We obtained demographic and medical information, including age, gender, race, marital status, and medication level in morphine equivalents, from the electronic health record. Medication level in morphine equivalents was recorded at the beginning of the intervention and again 6 months later. All analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 24 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) with P<.05 used to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Between-group differences. The Taper and MPC groups did not differ significantly on demographic variables, with mean ages, respectively, at 57 and 51 years, sex 56% and 50% female, race 74% and 79% white, and marital status 48% and 50% married.

We found significant differences between the Taper and MPC groups on total daily dose in morphine equivalents at baseline and at 6 months following initial intervention. The Levene’s test for equality of variances was statistically significant, indicating unequal variances between the groups. In our SPSS analyses, we therefore used the option “equal variances not assumed.” TABLE 1 lists resultant means, standard deviations, individual sample t-test scores, and confidence intervals. The MPC Group was taking significantly higher daily doses of morphine equivalents than the Taper Group both at baseline and at 6 months following initial intervention.

Within-group differences. Paired sample t tests indicated significant differences between baseline and 6-month average daily narcotic doses in morphine equivalents for the Taper Group. No significant difference was found between baseline and 6-month daily morphine equivalents for the MPC group. These results indicated that patients who continued opioid tapering with the FP significantly reduced their daily morphine equivalents over the 6 months of the study. Patients in the MPC Group reduced morphine equivalents over the 6 months, but the reduction was not statistically significant. Paired sample t test results are presented in TABLE 2.

Continue to: Patient retention

Patient retention. All but one of the 41 patients in the Tapering and MPC groups continued with the FP for the remainder of their health care needs. Contrary to some physicians’ fears, the patients in this study maintained continuity with their FP.

DISCUSSION

Results of this study indicate that an intervention consisting of a physician-patient discussion of ethical principles and evidence-based practice, followed by individualized opioid tapering per published guidelines, led to a significant reduction in opioid use in patients with CNCP. The Taper Group, which completed the intervention, exhibited significant morphine reductions between baseline and 6-month follow-up. This did not hold true for the MPC Group.

The MPC Group, despite participating in the discussion with the FP, chose not to complete the tapering program and was referred to a single-modality MPC where opioids were managed rather than tapered. While the MPC group reduced daily opioid dose levels, the reduction was not statistically significant. A possible reason for no difference within the MPC Group may be that they had greater dependence on opioids, as their baseline average daily dose was much higher than that in the Taper Group (173 mg vs 31 mg, respectively). Although we did not assess anxiety directly, we speculate that the MPC Group was more anxious about opioid reduction than the Taper Group, and that this anxiety potentially led 4 patients to opt out of the initial FP discussion and 14 patients to self-select out of the tapering program following the discussion.

The FP intervention was successful for the Taper Group. For MPC patients, an enhanced intervention including behavior health strategies13 might have reduced anxiety and increased motivation14 to continue tapering. Based on moderate-quality evidence, APS-AAPM guidelines strongly recommend that CNCP be viewed as a complex biopsychosocial condition. Therefore, clinicians who prescribe opioids should routinely integrate psychotherapeutic interventions, functional restoration, interdisciplinary therapy, and other adjunctive nonopioid therapies.6

Opioid tapering within multidisciplinary rehabilitation programs is possible without significant worsening of pain, mood, and function.15 Recently, an outpatient opioid-tapering support intervention showed promise for efficacy in reducing prescription opioid doses without resultant increases in pain intensity or pain interference.16

Continue to: The tapering protocol in our study...

The tapering protocol in our study and the inclusion of behavioral health co-interventions are also recommended by the 2016 guidelines published by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.17 More information on the similarities and differences among the various guidelines is available online.18,19

Caveats with our study. Patients’ entry into the Taper or MPC groups occurred through self-selection rather than random assignment. Thus, caution is recommended in interpreting findings of the FP intervention. And, we did not measure patients’ levels of pain, so differences between groups may have been possible. In addition, the number of patients per group was relatively small, which may have accounted for the lack of significance in the MPC Group findings. Conversely, significant reductions in opioid use in the small tapering sample suggests a relatively robust intervention, despite a lack of random assignment to treatment conditions.

These findings suggest that FPs can have a frank conversation about opioid use with their patients based on ethical principles and evidence-based practice, and employ a tapering protocol consistent with current opioid treatment guidelines. Furthermore, this approach appears not to jeopardize the patient-physician relationship.

CORRESPONDENCE

Thomas P. Guck, PhD, Creighton University School of Medicine, 2412 Cuming Street, Omaha, NE 68131; tpguck@creighton.edu.

ABSTRACT

Purpose Our study examined the efficacy of a primary-care intervention in reducing opioid use among patients who have chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP). We also recorded the intervention’s effect on patients’ decisions to leave (or stay) with the primary-care practice.

Methods A family physician (FP) identified 41 patients in his practice who had CNCP of at least 6 month’s duration and were using opioids. The intervention with each patient involved an initial discussion of ethical principles, evidence-based practice, and current published guidelines. Following the discussion, patients self-selected to participate with their FP in a continuing tapering program or to accept referral to a pain center for management of their opioid medications. Tapering ranged from a 10% reduction per week to a more rapid 25% to 50% reduction every few days. Twenty-seven patients continued tapering with their FP, and 6 months later were retrospectively placed in the Taper Group. Fourteen patients chose not to pursue the tapering option and were referred to a single-modality medical pain clinic (MPC). All patients had the option of staying with the FP for other medical care.

Results At baseline and again at 6 months post-initial intervention, the MPC Group was taking significantly higher daily doses of morphine equivalents than the Taper Group. The Taper Group at 6 months was taking significantly lower average daily narcotic doses in morphine equivalents than at baseline. No significant baseline-to-6 month differences were found in the MPC Group. Contrary to many physicians’ fear of losing patients following candid discussions about opioid use, 40 of the 41 patients continued with the FP for other health needs.

Conclusions FPs can frankly discuss opioid use with their patients based on ethical principles and evidence-based recommendations and employ a tapering protocol consistent with current opioid treatment guidelines without jeopardizing the patient-physician relationship.

[polldaddy:10180698]

Opioid prescriptions for chronic noncancer pain (CNCP) have increased significantly over the past 25 years in the United States.1 Despite methodologic concerns surrounding research on opioid harms, prescription opioid misuse among CNCP patients is estimated to be 21% to 29% and prescription addiction 8% to 12%.2 Tragically, with the overall increase in opioid use for CNCP, substance-related hospital admissions and deaths due to opioid overdose have also risen.3

Increased opioid use began in 1985 when the World Health Organization expanded its ethical mandate for pain relief in dying patients to include relief from all cancer pain.3 Opioid use then accelerated following Portenoy and Foley’s 1986 article4 and the 1997 consensus statement by the American Academy of Pain Medicine (AAPM) and the American Pain Society (APS),5 with both organizations arguing that opioids have a role in the treatment of CNCP. Increased use of opioids for CNCP continued throughout the 1990s and 2000s, as many states passed legislation removing sanctions on prescribing long-term and high-dose opioid therapy, and pharmaceutical companies aggressively marketed sustained-release opioids.3

A balanced approach to opioids. While acknowledging the serious public health problems of drug abuse, addiction, and diversion of opioids from licit to illicit uses, clinical research and regulation leaders have called for a balanced approach that recognizes the legitimate medical need for opioids for CNCP. In 2009 the APS, in partnership with the AAPM, published evidence-based guidelines on chronic opioid therapy (COT) for adults with CNCP.6 In developing these guidelines, a multidisciplinary panel of experts conducted systematic reviews of available evidence and made recommendations on formulating COT for individuals, initiating and titrating therapy, regularly monitoring patients, and managing opioid-related adverse effects. Additional recommendations addressed the use of therapies focusing on psychosocial factors. The APS-AAPM guidelines received the highest rating in a systematic review critically appraising 13 guidelines that address the use of opioids for CNCP.7

Continue to: When opioid use is prolonged...

When opioid use is prolonged. Most primary care physicians are aware of the risks of prolonged opioid use, and many have successfully tapered or discontinued opioid medications for patients in acute or pre-chronic stages of pain.8 However, many physicians face the challenge of patients who have used COT for a longer time. The APS-AAPM guidelines may help primary care physicians at any stage of treating CNCP patients.

METHODS

Purpose and design. This retrospective study, which reviewed pretest-posttest findings between and within study groups, received an exempt status from Creighton University’s institutional review board. We designed the study to determine the efficacy of an intervention protocol to reduce opioid use by patients with CNCP who had been in a family physician (FP)'s panel for quite some time. Furthermore, because a common fear among primary care providers is that raising concerns with patients about their opioid use may cause those patients to leave their panel,9 our study also recorded how many patients stayed with their FP after initiation of the opioid management protocol.

Subjects. This study tracked 41 patients with CNCP in 1 FP’s panel. Inclusion criteria for participation was: 1) presence of CNCP for at least 6 months, 2) current use of opioid medication for CNCP, 3) age of at least 16 years, and 4) ability to read and write English. Two exclusion criteria were the presence of a surgically correctable condition or an organic brain syndrome or psychosis.

Clinical intervention. The FP identified eligible patients in his practice that were taking opioids for CNCP and initiated a discussion with each of them emphasizing his desire to follow the ethical principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, respect for autonomy, and justice.10 The FP also presented his reasons for wanting the patient to stop using opioid medication. They included his beliefs that:

1) COT was not safe for the patient based on a growing body of published evidence of harm and death from COT3;

2) long-term use of opioids could lead to misuse, abuse, or addiction2;

3) prolonged opioid use paradoxically increases pain sensitivity that does not resolve

4) the patient’s current pain medications were not in line with published guidelines for use of opioids for CNCP.6

Initially, 45 patients were eligible for the study, but 4 declined participation before the intervention discussion and were immediately referred to a single-modality medical pain clinic (MPC). These patients were not included in subsequent analyses. Of the remaining 41 patients, all had a discussion with the MD about ethical principles, practice guidelines, and the importance of opioid tapering. After the discussion, patients decided whether to continue with the plan to taper their opioid therapy or to not taper their therapy and so receive a referral to an MPC.

Continue to: The 27 patients who chose to work with...

The 27 patients who chose to work with their FP started an individually tailored opioid-tapering program and were retrospectively placed in the Taper Group 6 months later. Tapering ranged from a slow 10% reduction in dosage per week to a more rapid 25% to 50% reduction every few days. Although evidence to guide specific recommendations on the rate of reduction is lacking, a slower rate may reduce unpleasant symptoms of opioid withdrawal.6 Following the patient-FP discussion, the 14 patients who chose not to pursue the tapering option were referred to an MPC for pain management, but could opt to remain with the FP for all other medical care. At 6 months post-discussion, we retrospectively assigned these 14 patients to the MPC Group.

Measures. We obtained demographic and medical information, including age, gender, race, marital status, and medication level in morphine equivalents, from the electronic health record. Medication level in morphine equivalents was recorded at the beginning of the intervention and again 6 months later. All analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 24 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) with P<.05 used to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

Between-group differences. The Taper and MPC groups did not differ significantly on demographic variables, with mean ages, respectively, at 57 and 51 years, sex 56% and 50% female, race 74% and 79% white, and marital status 48% and 50% married.

We found significant differences between the Taper and MPC groups on total daily dose in morphine equivalents at baseline and at 6 months following initial intervention. The Levene’s test for equality of variances was statistically significant, indicating unequal variances between the groups. In our SPSS analyses, we therefore used the option “equal variances not assumed.” TABLE 1 lists resultant means, standard deviations, individual sample t-test scores, and confidence intervals. The MPC Group was taking significantly higher daily doses of morphine equivalents than the Taper Group both at baseline and at 6 months following initial intervention.

Within-group differences. Paired sample t tests indicated significant differences between baseline and 6-month average daily narcotic doses in morphine equivalents for the Taper Group. No significant difference was found between baseline and 6-month daily morphine equivalents for the MPC group. These results indicated that patients who continued opioid tapering with the FP significantly reduced their daily morphine equivalents over the 6 months of the study. Patients in the MPC Group reduced morphine equivalents over the 6 months, but the reduction was not statistically significant. Paired sample t test results are presented in TABLE 2.

Continue to: Patient retention

Patient retention. All but one of the 41 patients in the Tapering and MPC groups continued with the FP for the remainder of their health care needs. Contrary to some physicians’ fears, the patients in this study maintained continuity with their FP.

DISCUSSION

Results of this study indicate that an intervention consisting of a physician-patient discussion of ethical principles and evidence-based practice, followed by individualized opioid tapering per published guidelines, led to a significant reduction in opioid use in patients with CNCP. The Taper Group, which completed the intervention, exhibited significant morphine reductions between baseline and 6-month follow-up. This did not hold true for the MPC Group.

The MPC Group, despite participating in the discussion with the FP, chose not to complete the tapering program and was referred to a single-modality MPC where opioids were managed rather than tapered. While the MPC group reduced daily opioid dose levels, the reduction was not statistically significant. A possible reason for no difference within the MPC Group may be that they had greater dependence on opioids, as their baseline average daily dose was much higher than that in the Taper Group (173 mg vs 31 mg, respectively). Although we did not assess anxiety directly, we speculate that the MPC Group was more anxious about opioid reduction than the Taper Group, and that this anxiety potentially led 4 patients to opt out of the initial FP discussion and 14 patients to self-select out of the tapering program following the discussion.

The FP intervention was successful for the Taper Group. For MPC patients, an enhanced intervention including behavior health strategies13 might have reduced anxiety and increased motivation14 to continue tapering. Based on moderate-quality evidence, APS-AAPM guidelines strongly recommend that CNCP be viewed as a complex biopsychosocial condition. Therefore, clinicians who prescribe opioids should routinely integrate psychotherapeutic interventions, functional restoration, interdisciplinary therapy, and other adjunctive nonopioid therapies.6

Opioid tapering within multidisciplinary rehabilitation programs is possible without significant worsening of pain, mood, and function.15 Recently, an outpatient opioid-tapering support intervention showed promise for efficacy in reducing prescription opioid doses without resultant increases in pain intensity or pain interference.16

Continue to: The tapering protocol in our study...

The tapering protocol in our study and the inclusion of behavioral health co-interventions are also recommended by the 2016 guidelines published by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.17 More information on the similarities and differences among the various guidelines is available online.18,19

Caveats with our study. Patients’ entry into the Taper or MPC groups occurred through self-selection rather than random assignment. Thus, caution is recommended in interpreting findings of the FP intervention. And, we did not measure patients’ levels of pain, so differences between groups may have been possible. In addition, the number of patients per group was relatively small, which may have accounted for the lack of significance in the MPC Group findings. Conversely, significant reductions in opioid use in the small tapering sample suggests a relatively robust intervention, despite a lack of random assignment to treatment conditions.

These findings suggest that FPs can have a frank conversation about opioid use with their patients based on ethical principles and evidence-based practice, and employ a tapering protocol consistent with current opioid treatment guidelines. Furthermore, this approach appears not to jeopardize the patient-physician relationship.

CORRESPONDENCE

Thomas P. Guck, PhD, Creighton University School of Medicine, 2412 Cuming Street, Omaha, NE 68131; tpguck@creighton.edu.

1. Manchikanti L, Helm S, Fellows B, et al. Opioid epidemic in the United States. Pain Physician. 2012;15:ES9-ES38.

2. Vowles KE, McEntee ML, Julnes PS, et al. Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: a systematic review and data synthesis. Pain. 2015;156:569-576.

3. Sullivan MD, Howe CQ. Opioid therapy for chronic pain in the United States: promises and perils. Pain. 2013;154:S94-S100.

4. Portenoy RK, Foley KM. Chronic use of opioid analgesics in non-malignant pain: report of 38 cases. Pain. 1986;25:171-186.

5. The use of opioids for the treatment of chronic pain. A consensus statement from the American Academy of Pain Medicine and the American Pain Society. Clin J Pain. 1997;13:6-8.

6. Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain. 2009;10:113-130.

7. Nuckols TK, Anderson L, Popescu I, et al. Opioid prescribing: a systematic review and critical appraisal of guidelines for chronic pain. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:38-47.

8. Hwang CS, Turner LW, Kruszewski SP, et al. Primary care physicians’ knowledge and attitudes regarding prescription opioid abuse and diversion. Clin J Pain. 2016;279-284.

9. Top 15 challenges facing physicians in 2015. Medical Economics. http://www.medicaleconomics.com/medical-economics/news/top-15-challenges-facing-physicians-2015?page=0,12. Accessed October 18, 2018.

10. Kotalik J. Controlling pain and reducing misuse of opioids: ethical considerations. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:381-385.

11. Angst MS, Clark JD. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:570-587.

12. Wachholtz A, Gonzalez G. Co-morbid pain and opioid addiction: long term effect of opioid maintenance on acute pain. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;145:143-149.

13. Hunter CL, Goodie JL, Oordt MS, Dobmeyer AC. Integrated Behavioral Health in Primary Care. 2nd ed. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2017.

14. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013.

15. Townsend CO, Kerkvliet JL, Bruce BK, et al. A longitudinal study of the efficacy of a comprehensive pain rehabilitation program with opioid withdrawal: comparison of treatment outcomes based on opioid use status at admission. Pain. 2008;140:177-189.

16. Sullivan MD, Turner JA, DiLodovico C, et al. Prescription opioid taper support for outpatients with chronic pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain. 2017;18:308-318.

17. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain - United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-49.

18. Barth KS, Guille C, McCauley J, et al. Targeting practitioners: a review of guidelines, training, and policy in pain management. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;173:S22-S30.

19. CDC. Common Elements in Guidelines for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain. Injury Prevention & Control: Prescription Drug Overdose 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/common-elements.html. Accessed October 18, 2018.

1. Manchikanti L, Helm S, Fellows B, et al. Opioid epidemic in the United States. Pain Physician. 2012;15:ES9-ES38.

2. Vowles KE, McEntee ML, Julnes PS, et al. Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: a systematic review and data synthesis. Pain. 2015;156:569-576.

3. Sullivan MD, Howe CQ. Opioid therapy for chronic pain in the United States: promises and perils. Pain. 2013;154:S94-S100.

4. Portenoy RK, Foley KM. Chronic use of opioid analgesics in non-malignant pain: report of 38 cases. Pain. 1986;25:171-186.

5. The use of opioids for the treatment of chronic pain. A consensus statement from the American Academy of Pain Medicine and the American Pain Society. Clin J Pain. 1997;13:6-8.

6. Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain. 2009;10:113-130.

7. Nuckols TK, Anderson L, Popescu I, et al. Opioid prescribing: a systematic review and critical appraisal of guidelines for chronic pain. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:38-47.

8. Hwang CS, Turner LW, Kruszewski SP, et al. Primary care physicians’ knowledge and attitudes regarding prescription opioid abuse and diversion. Clin J Pain. 2016;279-284.

9. Top 15 challenges facing physicians in 2015. Medical Economics. http://www.medicaleconomics.com/medical-economics/news/top-15-challenges-facing-physicians-2015?page=0,12. Accessed October 18, 2018.

10. Kotalik J. Controlling pain and reducing misuse of opioids: ethical considerations. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:381-385.

11. Angst MS, Clark JD. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:570-587.

12. Wachholtz A, Gonzalez G. Co-morbid pain and opioid addiction: long term effect of opioid maintenance on acute pain. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;145:143-149.

13. Hunter CL, Goodie JL, Oordt MS, Dobmeyer AC. Integrated Behavioral Health in Primary Care. 2nd ed. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2017.

14. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013.

15. Townsend CO, Kerkvliet JL, Bruce BK, et al. A longitudinal study of the efficacy of a comprehensive pain rehabilitation program with opioid withdrawal: comparison of treatment outcomes based on opioid use status at admission. Pain. 2008;140:177-189.

16. Sullivan MD, Turner JA, DiLodovico C, et al. Prescription opioid taper support for outpatients with chronic pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain. 2017;18:308-318.

17. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain - United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-49.

18. Barth KS, Guille C, McCauley J, et al. Targeting practitioners: a review of guidelines, training, and policy in pain management. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;173:S22-S30.

19. CDC. Common Elements in Guidelines for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain. Injury Prevention & Control: Prescription Drug Overdose 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/common-elements.html. Accessed October 18, 2018.

Anxiety and depression: Easing the burden in COPD patients

› Initiate both pharmacologic and psychological therapies for anxiety or depression coexisting with COPD to improve patient outcomes. B

› Consider buspirone as an alternative to benzodiazepines for anxiety coexistent with COPD. B

› Consider motivational interviewing as a behavioral approach to help patients who are ambivalent about or resistant to change. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › A 66-year-old man you have seen many times for issues related to his chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) comes in to your clinic for a routine visit. He has been taking budesonide/formoterol twice a day for the last 3 years; however, he has not always been compliant with his medications and has been hospitalized within the last 6 months for disease exacerbations. Today, he says he has difficulty falling asleep and often becomes short of breath, even when physically inactive. His wife, who is accompanying him today, tells you he has become increasingly distant over the past few months and is not as engaged at family outings, which he attributes to labored breathing. They’re both concerned about this change and ask for advice.

Despite the increased awareness that generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) are common comorbidities of COPD, they remain underdiagnosed and undertreated in patients with COPD. The results are increased rates of symptom exacerbation and rehospitalization.1 Family physicians, who are the primary caregivers for most patients with the disease,2 can maximize patients’ quality of life by recognizing comorbid mental illness, motivating and engaging patients in their disease management, and initiating appropriate treatment.

Anxiety and depression in COPD: A 2-way street

Several studies have assessed the prevalence of psychological disorders in patients with COPD. Affective disorders, mainly GAD and MDD, are the ones most commonly associated with poor COPD prognoses.3,4 GAD is at least 3 times more prevalent in patients with COPD than in the general US population,5 reaching upwards of 55%.1,6 Prevalence of MDD is also high, affecting approximately 40% of patients with the disease.1

GAD and MDD are more prevalent as comorbidities of COPD than they are with other chronic diseases such as orthopedic conditions, pulmonary tuberculosis, hypertension and heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and cancer.5,7-9 Patients with COPD, more so than patients with other serious chronic diseases, report heightened edginess, anxiousness, tiredness, distractibility, and irritability,5 perhaps owing in part to breathlessness and “air hunger.”10

The connection between COPD and GAD or MDD is not unidirectional, with progression of lung disease exacerbating its psychological comorbidities. The interaction is reciprocal, as clarified by Atlantis, et al, in a 2013 systematic review and meta-analysis that assessed key variables in the development of COPD and GAD or MDD.11

COPD increases the risk of MDD, which is associated with increased tobacco consumption, poor adherence with COPD medications, and decreased physical activity.11 Compounding the problem of inactivity is the fact that COPD—particularly longstanding disease—can lead to volume reductions in the anterior cingulate cortex of patients, which correlates with a persistent fear of performing physical activity.12 MDD in the setting of COPD also complicates the already complex interplay between nicotine dependence and attempts at smoking cessation.11

GAD/MDD worsens COPD outcomes

Comorbid GAD and MDD increase demands on our health care system and decrease the quality of life for patients with COPD. Anxious or depressed patients have higher 30-day readmission rates and less frequent outpatient follow-up than COPD patients without these mental comorbidities.6 Patients with comorbidities tend to have a higher prevalence of systemic symptoms independent of COPD severity,7 exhibit poorer physical and social functioning,13 and experience greater impairment of quality of life than patients with lung dysfunction alone.1,14 Patients with GAD or MDD have a 43% increased risk of any adverse COPD outcome, which can include exacerbations, COPD-related diagnoses (eg, emphysema), new anxiety or depression events, and death.11 Specifically, the risk of a COPD exacerbation rises by 31% in patients with comorbid GAD or MDD, and risk of death in those with comorbid MDD increases by 83%.11

GAD or MDD with COPD increases health care utilization and costs per patient when compared with patients who have COPD alone.9 Annual physician visits, emergency-room visits, and hospitalizations for any cause are higher in anxious or depressed COPD patients, and they have a 77% increased chance annually of a COPD-related hospitalization.9 Annual COPD-related health care costs for patients with GAD or MDD are significantly higher than the average COPD-related costs for patients without depression or anxiety, leading to significantly increased all-cause health care costs: $28,961 vs $22,512.9 Addressing and managing comorbid GAD or MDD in COPD patients could substantially reduce health care costs.

Be vigilant for anxiety, depression—even when COPD is mild

One reason comorbid GAD or MDD may be overlooked and underdiagnosed is that the symptoms can overlap those of COPD. In cases where suspicion of GAD or MDD is warranted, providers must keep separate the diagnostic inquiries for COPD and these comorbidities.6

Somatic symptoms of anxiety, such as hyperventilation, shortness of breath, and sweating, may easily be attributed to pulmonary disease instead of a psychological disorder. Differentiating the 2 processes becomes more difficult with patients younger than 60 years, as they are more likely to experience symptoms of GAD or MDD than older patients, regardless of COPD severity.15 Therefore, when assessing COPD patients, physicians need to be more vigilant for anxiety and depression, even in the mildest cases.14

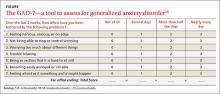

Several methods exist for assessing anxiety and depression, including the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener 7 (GAD-7) and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) 2 or 9.16 All PHQ and GAD-7 screeners and translations are downloadable from www.phqscreeners.com/select-screener and permission is not required to reproduce, translate, display, or distribute them (FIGURE).16 Other anxiety and depression screening instruments are also available.

No one method has been shown to be most effective for rapid screening, and the physician’s comfort level or familiarity with a particular assessment tool may guide selection. One advantage of short screening instruments is that they can be incorporated into electronic health records for easy use across continuity visits. Although routine screening for these mental comorbidities takes slightly more time—especially in high-volume family practice clinics—it needs to become standard practice to protect patients’ quality of life.

Managing psychiatric conditions in COPD

Treatment for GAD and MDD in COPD is often suboptimal and may diminish a patient’s quality of life. In one study, COPD patients with a mental illness were 46% less likely than those with COPD alone to receive medications such as short- or long-acting bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids.17 Therapy for both the physiologic abnormalities and mental disturbances should be initiated promptly to maintain an acceptable state of health.

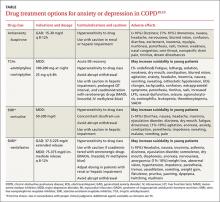

Pharmacotherapy. Reluctance to give traditional psychiatric medications to COPD patients contributes to the under-treatment of mental comorbidities. While benzodiazepines are generally not recommended—especially in severe COPD cases due to their sedative effect on respiratory drive—alternatives such as buspirone, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) have been shown to effectively reduce GAD, MDD, and dyspnea in these patients5,14(TABLE18,19).

Non-pharmacotherapy approaches. Having patients apply behavioral-modification principles to their own behavior20 has been proposed as a standard of care in the treatment of COPD.21 A recent systematic review found that self-management (behavior change) interventions in patients with COPD improved health-related quality of life, reduced hospital admissions, and helped alleviate dyspnea.22 While that review could not make clear recommendations regarding the most effective form and content of self-management in COPD,22 patient engagement and motivation in creating treatment goals are considered critical ingredients for effective self-management.21

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is an evidence-based behavioral approach designed for patients who are ambivalent about or resistant to change.23 MI works by supporting a patient’s autonomy and by activating his/her own internal motivation for change or adherence to treatment. In MI, the physician’s involvement with the patient relies on collaboration, evocation, and autonomy, rather than confrontation, education, and authority. MI involves exploration more than exhortation, and support rather than persuasion or argument. The overall goal of MI is to increase intrinsic motivation so that change arises from within and serves the patient’s goals and values.23

Benzo, et al, provide a very detailed description of a self-management process that includes MI.21 Their protocol proved to be feasible in severe COPD and helped increase patient engagement and commitment to self-management.21 This finding and similar evidence of MI’s effectiveness in a variety of other health conditions suggest that pharmacotherapy and cognitive-behavior therapy can be delivered in combination with an MI approach.

Self-management depends on a patient’s readiness to implement behavioral changes. Patients engaged in unhealthy behavior may be reluctant to change at a particular time, so the physician may focus efforts on such behaviors as self-monitoring or examining values that may lead to future behavior change.

For example, a patient may not want to stop smoking, but the physician’s willingness to ask about smoking in subsequent visits may catch the patient at a time when motivation has changed—eg, perhaps there is a new child in the home, prompting a recognition that smoking is now inconsistent with one’s values and can be resolved with smoking cessation. Awareness of an individual’s baseline behavior and readiness to change assists physicians and other health professionals in tailoring interventions for the most favorable outcome.

Several other non-pharmacologic methods to reduce symptoms of GAD and MDD in patients with COPD have been studied and supported by the literature.

- Progressive muscle relaxation, stress management, biofeedback, and guided imagery have been shown to decrease symptoms of anxiety, dyspnea, and airway obstruction.5,14

- Pulmonary rehabilitation programs including psychotherapy sessions have also relieved symptoms of GAD and MDD for patients with COPD.

- Programs that include physiotherapy, physical exercise (arm and leg exercise, aerobic conditioning, flexibility training), patient education, and psychotherapy sessions have significantly lowered GAD and MDD scores when compared with similar rehabilitation programs not offering psychotherapy.24

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy has been variably effective in treating comorbid GAD and MDD, with studies citing either superiority5 or equivalence25 to COPD education alone.

Increasingly, psychologists have been integrated into primary care with implementation of the Patient-Centered Medical Home.26 However, if primary care physicians do not have behavioral specialists available, they can contact the American Psychological Association, their state psychological association, or professional organizations, such as the Society of Behavioral Medicine, for referral to professionals trained in behavioral self-management skills.

Initiation of treatment, whether pharmacological or non-pharmacological, and emphasis on self-management of the disease can greatly improve patients' perceptions of their condition and overall quality of life.

CASE › The patient screens positive for GAD and you give him a prescription for venlafaxine to begin immediately. Using an MI approach, you help the patient clarify that being more engaged with his family is important to him. Acknowledging that your recommendations are consistent with his values, the patient agrees to pursue pulmonary rehabilitation and, with the aid of a behavioral health specialist, learn self-management techniques for medication adherence and social reengagement.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ms. Sydney Marsh, 3009 S 35th Ave., Omaha, NE 68105; sydneymarsh@creighton.edu.

1. Yohannes AM, Willgoss TG, Baldwin RC, et al. Depression and anxiety in chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, relevance, clinical implications and management principles. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25:1209-1221.

2. Punturieri A, Croxton TL, Weinmann G, et al. The changing face of COPD. Am Fam Physician. 2007;1:315-316.

3. Willgoss TG, Yohannes AM. Anxiety disorders in patients with COPD: a systematic review. Respir Care. 2013;58:858-866.

4. Porthirat C, Chaiwong W, Phetsuk N, et al. Major affective disorders in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease compared with other chronic respiratory diseases. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1583-1590.

5. Brenes GA. Anxiety and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, impact, and treatment. Psychosom Med. 2003; 65:963-970.

6. Singh G, Zhang W, Kuo YF, et al. Association of psychological disorders with 30-day readmission rates in patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Chest. 2015;Jul 23:[Epub ahead of print].

7. Vögele C, von Leupoldt A. Mental disorders in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2008;102:764-773.

8. Aydin IO, Ulusahin A. Depression, anxiety comorbidity, and disability in tuberculosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: applicability of GHQ-12. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23:77-83.

9. Dalal AA, Shah M, Lunacsek O, et al. Clinical and economic burden of depression/anxiety in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients within a managed care population. COPD. 2011;8:293-299.

10. Janssen DJA, Wouters EFM, Spruit MA. Psychosocial consequences of living with breathlessness due to advanced disease. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2015;9:232-237.

11. Atlantis E, Fahey P, Cochrane B, et al. Bidirectional associations between clinically relevant depression or anxiety and COPD. Chest. 2013;144:766-777.

12. Esser RW, Stoeckel MC, Kirsten A, et al. Structural brain changes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest. 2015;Jul 23:[Epub ahead of print].

13. Ng TP, Niti M, Tan WC, et al. Depressive symptoms and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effect on mortality, hospital readmission, symptom burden, functional status, and quality of life. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:60-67.

14. Kim HF, Kunik ME, Molinari VA, et al. Functional impairment in COPD patients. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:465-471.

15. Cleland JA, Lee AJ, Hall S. Associations of depression and anxiety with gender, age, health-related quality of life and symptoms in primary care COPD patients. Fam Pract. 2007;24:217-223.

16. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB et al. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:345-359.

17. Ajmera M, Sambamoorthi U, Metzger A, et al. Multimorbidity and COPD medication receipt among Medicaid beneficiaries with newly diagnosed COPD. Respir Care. 2015;60:1592-1602.

18. Medscape. Psychiatrics. Available at: http://reference.medscape.com/drugs/psychiatrics. Accessed March 1, 2016.

19. Physicians’ Desk Reference. Available at: http://www.pdr.net. Accessed March 1, 2016.

20. Kazdin AE. Behavior Modification in Applied Settings. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning; 2001.

21. Benzo R, Vickers K, Ernst D, et al. Development and feasibility of a self-management intervention for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease delivered with motivational interviewing strategies. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2013;33:113-123.

22. Zwerink M, Brusse-Keizer M, van der Valk PD, et al. Self management for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database System Rev. 2014;(3):CD002990.

23. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013.

24. de Godoy DV, de Godoy RF. A randomized controlled trial of the effect of psychotherapy on anxiety and depression in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:1154-1157.

25. Kunik ME, Veazey C, Cully JA, et al. COPD education and cognitive behavioral therapy group treatment for clinically significant symptoms of depression and anxiety in COPD patients: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2008;38:385-396.

26. McDaniel SH, Fogarty CT. What primary care psychology has to offer the patient-centered medical home. Prof Psych Res Pract. 2009;40:483-492.

› Initiate both pharmacologic and psychological therapies for anxiety or depression coexisting with COPD to improve patient outcomes. B

› Consider buspirone as an alternative to benzodiazepines for anxiety coexistent with COPD. B

› Consider motivational interviewing as a behavioral approach to help patients who are ambivalent about or resistant to change. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › A 66-year-old man you have seen many times for issues related to his chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) comes in to your clinic for a routine visit. He has been taking budesonide/formoterol twice a day for the last 3 years; however, he has not always been compliant with his medications and has been hospitalized within the last 6 months for disease exacerbations. Today, he says he has difficulty falling asleep and often becomes short of breath, even when physically inactive. His wife, who is accompanying him today, tells you he has become increasingly distant over the past few months and is not as engaged at family outings, which he attributes to labored breathing. They’re both concerned about this change and ask for advice.

Despite the increased awareness that generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) are common comorbidities of COPD, they remain underdiagnosed and undertreated in patients with COPD. The results are increased rates of symptom exacerbation and rehospitalization.1 Family physicians, who are the primary caregivers for most patients with the disease,2 can maximize patients’ quality of life by recognizing comorbid mental illness, motivating and engaging patients in their disease management, and initiating appropriate treatment.

Anxiety and depression in COPD: A 2-way street

Several studies have assessed the prevalence of psychological disorders in patients with COPD. Affective disorders, mainly GAD and MDD, are the ones most commonly associated with poor COPD prognoses.3,4 GAD is at least 3 times more prevalent in patients with COPD than in the general US population,5 reaching upwards of 55%.1,6 Prevalence of MDD is also high, affecting approximately 40% of patients with the disease.1

GAD and MDD are more prevalent as comorbidities of COPD than they are with other chronic diseases such as orthopedic conditions, pulmonary tuberculosis, hypertension and heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and cancer.5,7-9 Patients with COPD, more so than patients with other serious chronic diseases, report heightened edginess, anxiousness, tiredness, distractibility, and irritability,5 perhaps owing in part to breathlessness and “air hunger.”10

The connection between COPD and GAD or MDD is not unidirectional, with progression of lung disease exacerbating its psychological comorbidities. The interaction is reciprocal, as clarified by Atlantis, et al, in a 2013 systematic review and meta-analysis that assessed key variables in the development of COPD and GAD or MDD.11

COPD increases the risk of MDD, which is associated with increased tobacco consumption, poor adherence with COPD medications, and decreased physical activity.11 Compounding the problem of inactivity is the fact that COPD—particularly longstanding disease—can lead to volume reductions in the anterior cingulate cortex of patients, which correlates with a persistent fear of performing physical activity.12 MDD in the setting of COPD also complicates the already complex interplay between nicotine dependence and attempts at smoking cessation.11

GAD/MDD worsens COPD outcomes

Comorbid GAD and MDD increase demands on our health care system and decrease the quality of life for patients with COPD. Anxious or depressed patients have higher 30-day readmission rates and less frequent outpatient follow-up than COPD patients without these mental comorbidities.6 Patients with comorbidities tend to have a higher prevalence of systemic symptoms independent of COPD severity,7 exhibit poorer physical and social functioning,13 and experience greater impairment of quality of life than patients with lung dysfunction alone.1,14 Patients with GAD or MDD have a 43% increased risk of any adverse COPD outcome, which can include exacerbations, COPD-related diagnoses (eg, emphysema), new anxiety or depression events, and death.11 Specifically, the risk of a COPD exacerbation rises by 31% in patients with comorbid GAD or MDD, and risk of death in those with comorbid MDD increases by 83%.11

GAD or MDD with COPD increases health care utilization and costs per patient when compared with patients who have COPD alone.9 Annual physician visits, emergency-room visits, and hospitalizations for any cause are higher in anxious or depressed COPD patients, and they have a 77% increased chance annually of a COPD-related hospitalization.9 Annual COPD-related health care costs for patients with GAD or MDD are significantly higher than the average COPD-related costs for patients without depression or anxiety, leading to significantly increased all-cause health care costs: $28,961 vs $22,512.9 Addressing and managing comorbid GAD or MDD in COPD patients could substantially reduce health care costs.

Be vigilant for anxiety, depression—even when COPD is mild

One reason comorbid GAD or MDD may be overlooked and underdiagnosed is that the symptoms can overlap those of COPD. In cases where suspicion of GAD or MDD is warranted, providers must keep separate the diagnostic inquiries for COPD and these comorbidities.6

Somatic symptoms of anxiety, such as hyperventilation, shortness of breath, and sweating, may easily be attributed to pulmonary disease instead of a psychological disorder. Differentiating the 2 processes becomes more difficult with patients younger than 60 years, as they are more likely to experience symptoms of GAD or MDD than older patients, regardless of COPD severity.15 Therefore, when assessing COPD patients, physicians need to be more vigilant for anxiety and depression, even in the mildest cases.14

Several methods exist for assessing anxiety and depression, including the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener 7 (GAD-7) and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) 2 or 9.16 All PHQ and GAD-7 screeners and translations are downloadable from www.phqscreeners.com/select-screener and permission is not required to reproduce, translate, display, or distribute them (FIGURE).16 Other anxiety and depression screening instruments are also available.

No one method has been shown to be most effective for rapid screening, and the physician’s comfort level or familiarity with a particular assessment tool may guide selection. One advantage of short screening instruments is that they can be incorporated into electronic health records for easy use across continuity visits. Although routine screening for these mental comorbidities takes slightly more time—especially in high-volume family practice clinics—it needs to become standard practice to protect patients’ quality of life.

Managing psychiatric conditions in COPD

Treatment for GAD and MDD in COPD is often suboptimal and may diminish a patient’s quality of life. In one study, COPD patients with a mental illness were 46% less likely than those with COPD alone to receive medications such as short- or long-acting bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids.17 Therapy for both the physiologic abnormalities and mental disturbances should be initiated promptly to maintain an acceptable state of health.

Pharmacotherapy. Reluctance to give traditional psychiatric medications to COPD patients contributes to the under-treatment of mental comorbidities. While benzodiazepines are generally not recommended—especially in severe COPD cases due to their sedative effect on respiratory drive—alternatives such as buspirone, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) have been shown to effectively reduce GAD, MDD, and dyspnea in these patients5,14(TABLE18,19).

Non-pharmacotherapy approaches. Having patients apply behavioral-modification principles to their own behavior20 has been proposed as a standard of care in the treatment of COPD.21 A recent systematic review found that self-management (behavior change) interventions in patients with COPD improved health-related quality of life, reduced hospital admissions, and helped alleviate dyspnea.22 While that review could not make clear recommendations regarding the most effective form and content of self-management in COPD,22 patient engagement and motivation in creating treatment goals are considered critical ingredients for effective self-management.21

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is an evidence-based behavioral approach designed for patients who are ambivalent about or resistant to change.23 MI works by supporting a patient’s autonomy and by activating his/her own internal motivation for change or adherence to treatment. In MI, the physician’s involvement with the patient relies on collaboration, evocation, and autonomy, rather than confrontation, education, and authority. MI involves exploration more than exhortation, and support rather than persuasion or argument. The overall goal of MI is to increase intrinsic motivation so that change arises from within and serves the patient’s goals and values.23

Benzo, et al, provide a very detailed description of a self-management process that includes MI.21 Their protocol proved to be feasible in severe COPD and helped increase patient engagement and commitment to self-management.21 This finding and similar evidence of MI’s effectiveness in a variety of other health conditions suggest that pharmacotherapy and cognitive-behavior therapy can be delivered in combination with an MI approach.

Self-management depends on a patient’s readiness to implement behavioral changes. Patients engaged in unhealthy behavior may be reluctant to change at a particular time, so the physician may focus efforts on such behaviors as self-monitoring or examining values that may lead to future behavior change.