User login

Breast cancer screening in women receiving antipsychotics

Women with severe mental illness (SMI) are more likely to develop breast cancer and often have more advanced stages of breast cancer when it is detected.1 Antipsychotics have a wide variety of FDA-approved indications and many important life-saving properties. However, patients treated with antipsychotic medications that increase prolactin levels require special consideration with regards to referral for breast cancer screening. Although no clear causal link between antipsychotic use and breast cancer has been established, antipsychotics that raise serum prolactin levels (haloperidol, iloperidone, lurasidone, olanzapine, paliperidone, risperidone) are associated with a higher risk of breast cancer than antipsychotics that produce smaller increases in prolactin levels (aripiprazole, asenapine, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, clozapine, quetiapine, and ziprasidone).2,3 Risperidone and paliperidone have the highest propensities to increase prolactin (45 to >100 ng/mL), whereas other second-generation antipsychotics are associated with only modest elevations.4 Prolonged exposure to high serum prolactin levels should be avoided in women due to the increased risk for breast cancer.2,3 Although there are no clear rules regarding which number or cluster of personal risk factors necessitates a further risk assessment for breast cancer, women receiving antipsychotics (especially those age ≥40) can be referred for further assessment. An individualized, patient-centered approach should be used.

Recognize risk factors

Patients with SMI often need to take a regimen of medications, including antipsychotics, for weeks or months to stabilize their symptoms. Once a woman with SMI is stabilized, consider referral to a clinic that can comprehensively assess for breast cancer risk. Nonmodifiable risk factors include older age, certain genetic mutations (BRCA1 and BRCA2), early menarche, late menopause, high breast tissue density as detected by mammography, a family history of breast cancer, and exposure to radiation.5,6 Modifiable risk factors include physical inactivity, being overweight or obese, hormonal exposure, drinking alcohol, and the presence of certain factors in the patient’s reproductive history (first pregnancy after age 30, not breastfeeding, and never having a full-term pregnancy).2,3 When making such referrals, it is important to avoid making the patient feel alarmed or frightened of antipsychotics. Instead, explain that a referral for breast cancer screening is routine.

When to refer

All women age ≥40 should be offered a referral to a clinic that can provide screening mammography. If a woman has pain, detects a lump in her breast, has a bloody discharge from the nipple, or has changes in the shape or texture of the nipple or breast, a more urgent referral should be made.4 The most important thing to remember is that early breast lesion detection can be life-saving and can avert the need for more invasive surgeries as well as exposure to chemotherapy and radiation.

What to do when prolactin is elevated

Ongoing monitoring of serum prolactin levels can help ensure that the patient’s levels remain in a normal range (<25 ng/mL).2,3,5,6 If hyperprolactinemia is detected, consider switching to an antipsychotic less likely to increase prolactin. Alternatively, the addition of aripiprazole/brexpiprazole or a dopamine agonist as combination therapy can be considered to rapidly restore normal prolactin levels.2 Such changes should be carefully considered because patients may decompensate if antipsychotics are abruptly switched. An individualized risk vs benefit analysis is necessary for any patient in this situation. Risks include not only the recurrence of psychiatric symptoms but also a potential loss of their current level of functioning. Patients may need to continue to take an antipsychotic that is more likely to increase prolactin, in which case close monitoring is advised as well as collaboration with other physicians and members of the patient’s care team. Involving the patient’s support system is helpful.

1. Weinstein LC, Stefancic A, Cunningham AT, et al. Cancer screening, prevention, and treatment in people with mental illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):134-151.

2. Rahman T, Sahrmann JM, Olsen MA, et al. Risk of breast cancer with prolactin elevating antipsychotic drugs: an observational study of US women (ages 18–64 years). J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2022;42(1):7-16.

3. Rahman T, Clevenger CV, Kaklamani V, et al. Antipsychotic treatment in breast cancer patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(6):616-621.

4. Peuskens J, Pani L, Detraux J, et al. The effects of novel and newly approved antipsychotics on serum prolactin levels: a comprehensive review. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(5):421-453.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. Breast cancer. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/index.htm

6. Steiner E, Klubert D, Knutson D. Assessing breast cancer risk in women. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(12):1361-1366.

Women with severe mental illness (SMI) are more likely to develop breast cancer and often have more advanced stages of breast cancer when it is detected.1 Antipsychotics have a wide variety of FDA-approved indications and many important life-saving properties. However, patients treated with antipsychotic medications that increase prolactin levels require special consideration with regards to referral for breast cancer screening. Although no clear causal link between antipsychotic use and breast cancer has been established, antipsychotics that raise serum prolactin levels (haloperidol, iloperidone, lurasidone, olanzapine, paliperidone, risperidone) are associated with a higher risk of breast cancer than antipsychotics that produce smaller increases in prolactin levels (aripiprazole, asenapine, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, clozapine, quetiapine, and ziprasidone).2,3 Risperidone and paliperidone have the highest propensities to increase prolactin (45 to >100 ng/mL), whereas other second-generation antipsychotics are associated with only modest elevations.4 Prolonged exposure to high serum prolactin levels should be avoided in women due to the increased risk for breast cancer.2,3 Although there are no clear rules regarding which number or cluster of personal risk factors necessitates a further risk assessment for breast cancer, women receiving antipsychotics (especially those age ≥40) can be referred for further assessment. An individualized, patient-centered approach should be used.

Recognize risk factors

Patients with SMI often need to take a regimen of medications, including antipsychotics, for weeks or months to stabilize their symptoms. Once a woman with SMI is stabilized, consider referral to a clinic that can comprehensively assess for breast cancer risk. Nonmodifiable risk factors include older age, certain genetic mutations (BRCA1 and BRCA2), early menarche, late menopause, high breast tissue density as detected by mammography, a family history of breast cancer, and exposure to radiation.5,6 Modifiable risk factors include physical inactivity, being overweight or obese, hormonal exposure, drinking alcohol, and the presence of certain factors in the patient’s reproductive history (first pregnancy after age 30, not breastfeeding, and never having a full-term pregnancy).2,3 When making such referrals, it is important to avoid making the patient feel alarmed or frightened of antipsychotics. Instead, explain that a referral for breast cancer screening is routine.

When to refer

All women age ≥40 should be offered a referral to a clinic that can provide screening mammography. If a woman has pain, detects a lump in her breast, has a bloody discharge from the nipple, or has changes in the shape or texture of the nipple or breast, a more urgent referral should be made.4 The most important thing to remember is that early breast lesion detection can be life-saving and can avert the need for more invasive surgeries as well as exposure to chemotherapy and radiation.

What to do when prolactin is elevated

Ongoing monitoring of serum prolactin levels can help ensure that the patient’s levels remain in a normal range (<25 ng/mL).2,3,5,6 If hyperprolactinemia is detected, consider switching to an antipsychotic less likely to increase prolactin. Alternatively, the addition of aripiprazole/brexpiprazole or a dopamine agonist as combination therapy can be considered to rapidly restore normal prolactin levels.2 Such changes should be carefully considered because patients may decompensate if antipsychotics are abruptly switched. An individualized risk vs benefit analysis is necessary for any patient in this situation. Risks include not only the recurrence of psychiatric symptoms but also a potential loss of their current level of functioning. Patients may need to continue to take an antipsychotic that is more likely to increase prolactin, in which case close monitoring is advised as well as collaboration with other physicians and members of the patient’s care team. Involving the patient’s support system is helpful.

Women with severe mental illness (SMI) are more likely to develop breast cancer and often have more advanced stages of breast cancer when it is detected.1 Antipsychotics have a wide variety of FDA-approved indications and many important life-saving properties. However, patients treated with antipsychotic medications that increase prolactin levels require special consideration with regards to referral for breast cancer screening. Although no clear causal link between antipsychotic use and breast cancer has been established, antipsychotics that raise serum prolactin levels (haloperidol, iloperidone, lurasidone, olanzapine, paliperidone, risperidone) are associated with a higher risk of breast cancer than antipsychotics that produce smaller increases in prolactin levels (aripiprazole, asenapine, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, clozapine, quetiapine, and ziprasidone).2,3 Risperidone and paliperidone have the highest propensities to increase prolactin (45 to >100 ng/mL), whereas other second-generation antipsychotics are associated with only modest elevations.4 Prolonged exposure to high serum prolactin levels should be avoided in women due to the increased risk for breast cancer.2,3 Although there are no clear rules regarding which number or cluster of personal risk factors necessitates a further risk assessment for breast cancer, women receiving antipsychotics (especially those age ≥40) can be referred for further assessment. An individualized, patient-centered approach should be used.

Recognize risk factors

Patients with SMI often need to take a regimen of medications, including antipsychotics, for weeks or months to stabilize their symptoms. Once a woman with SMI is stabilized, consider referral to a clinic that can comprehensively assess for breast cancer risk. Nonmodifiable risk factors include older age, certain genetic mutations (BRCA1 and BRCA2), early menarche, late menopause, high breast tissue density as detected by mammography, a family history of breast cancer, and exposure to radiation.5,6 Modifiable risk factors include physical inactivity, being overweight or obese, hormonal exposure, drinking alcohol, and the presence of certain factors in the patient’s reproductive history (first pregnancy after age 30, not breastfeeding, and never having a full-term pregnancy).2,3 When making such referrals, it is important to avoid making the patient feel alarmed or frightened of antipsychotics. Instead, explain that a referral for breast cancer screening is routine.

When to refer

All women age ≥40 should be offered a referral to a clinic that can provide screening mammography. If a woman has pain, detects a lump in her breast, has a bloody discharge from the nipple, or has changes in the shape or texture of the nipple or breast, a more urgent referral should be made.4 The most important thing to remember is that early breast lesion detection can be life-saving and can avert the need for more invasive surgeries as well as exposure to chemotherapy and radiation.

What to do when prolactin is elevated

Ongoing monitoring of serum prolactin levels can help ensure that the patient’s levels remain in a normal range (<25 ng/mL).2,3,5,6 If hyperprolactinemia is detected, consider switching to an antipsychotic less likely to increase prolactin. Alternatively, the addition of aripiprazole/brexpiprazole or a dopamine agonist as combination therapy can be considered to rapidly restore normal prolactin levels.2 Such changes should be carefully considered because patients may decompensate if antipsychotics are abruptly switched. An individualized risk vs benefit analysis is necessary for any patient in this situation. Risks include not only the recurrence of psychiatric symptoms but also a potential loss of their current level of functioning. Patients may need to continue to take an antipsychotic that is more likely to increase prolactin, in which case close monitoring is advised as well as collaboration with other physicians and members of the patient’s care team. Involving the patient’s support system is helpful.

1. Weinstein LC, Stefancic A, Cunningham AT, et al. Cancer screening, prevention, and treatment in people with mental illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):134-151.

2. Rahman T, Sahrmann JM, Olsen MA, et al. Risk of breast cancer with prolactin elevating antipsychotic drugs: an observational study of US women (ages 18–64 years). J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2022;42(1):7-16.

3. Rahman T, Clevenger CV, Kaklamani V, et al. Antipsychotic treatment in breast cancer patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(6):616-621.

4. Peuskens J, Pani L, Detraux J, et al. The effects of novel and newly approved antipsychotics on serum prolactin levels: a comprehensive review. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(5):421-453.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. Breast cancer. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/index.htm

6. Steiner E, Klubert D, Knutson D. Assessing breast cancer risk in women. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(12):1361-1366.

1. Weinstein LC, Stefancic A, Cunningham AT, et al. Cancer screening, prevention, and treatment in people with mental illness. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):134-151.

2. Rahman T, Sahrmann JM, Olsen MA, et al. Risk of breast cancer with prolactin elevating antipsychotic drugs: an observational study of US women (ages 18–64 years). J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2022;42(1):7-16.

3. Rahman T, Clevenger CV, Kaklamani V, et al. Antipsychotic treatment in breast cancer patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(6):616-621.

4. Peuskens J, Pani L, Detraux J, et al. The effects of novel and newly approved antipsychotics on serum prolactin levels: a comprehensive review. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(5):421-453.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. Breast cancer. Accessed June 1, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/index.htm

6. Steiner E, Klubert D, Knutson D. Assessing breast cancer risk in women. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(12):1361-1366.

Can mood stabilizers reduce chronic pain in patients with bipolar disorder?

Misuse of prescription opioids has led to a staggering number of patients developing addiction, which the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) have identified as a health care crisis. In the United States, approximately 29% of patients prescribed an opioid misuse it, and approximately 80% of heroin users started with prescription opioids.1,2 The NIH and HHS have outlined 5 priorities to help resolve this crisis:

- Improve access to prevention, treatment, and recovery support services

- Increase availability and distribution of overdose-reversing medications

- As the epidemic changes, strengthen what we know with improved public health surveillance

- Support research that advances the understanding of pain and addiction and that develops new treatments and interventions

- Improve pain management by utilizing evidence-based practices and reducing opioid misuse and opiate-related harm.3

Treating chronic pain in patients with bipolar disorder

At the Missouri University Psychiatric Center, an inpatient psychiatric ward, we recently conducted a retrospective cohort study to identify effective alternatives for treating pain, and to decrease opioid-related harm. Our study focused on 73 inpatients experiencing exacerbation of bipolar I disorder who also had chronic pain. These patients were treated with mood stabilizers, including lithium and carbamazepine. Patients also were taking medications, as needed, for agitation and their home medications for various medical problems. Selection of mood stabilizer therapy was non-random by standard of care based on best clinical practices. Dosing was based on blood-level monitoring adjusted to maintain therapeutic levels while receiving inpatient care. The average duration of inpatient treatment was approximately 1 to 5 weeks.

Pain was measured at baseline and compared with daily pain scores after mood stabilizer therapy using a 10-point scale, with 0 for no pain to 10 for worse pain, for the duration of the admission As expected based on the findings of previous research, carbamazepine resulted in a decrease in average daily pain score by 1.25 points after treatment (P = .048; F value = 4.3; F-crit = 4.23; calculated by one-way analysis of variance). However, patients who received lithium experienced a greater decrease in average daily pain score, by 2.17 points after treatment (P = .00035; F value = 14.56; F-crit = 4.02).

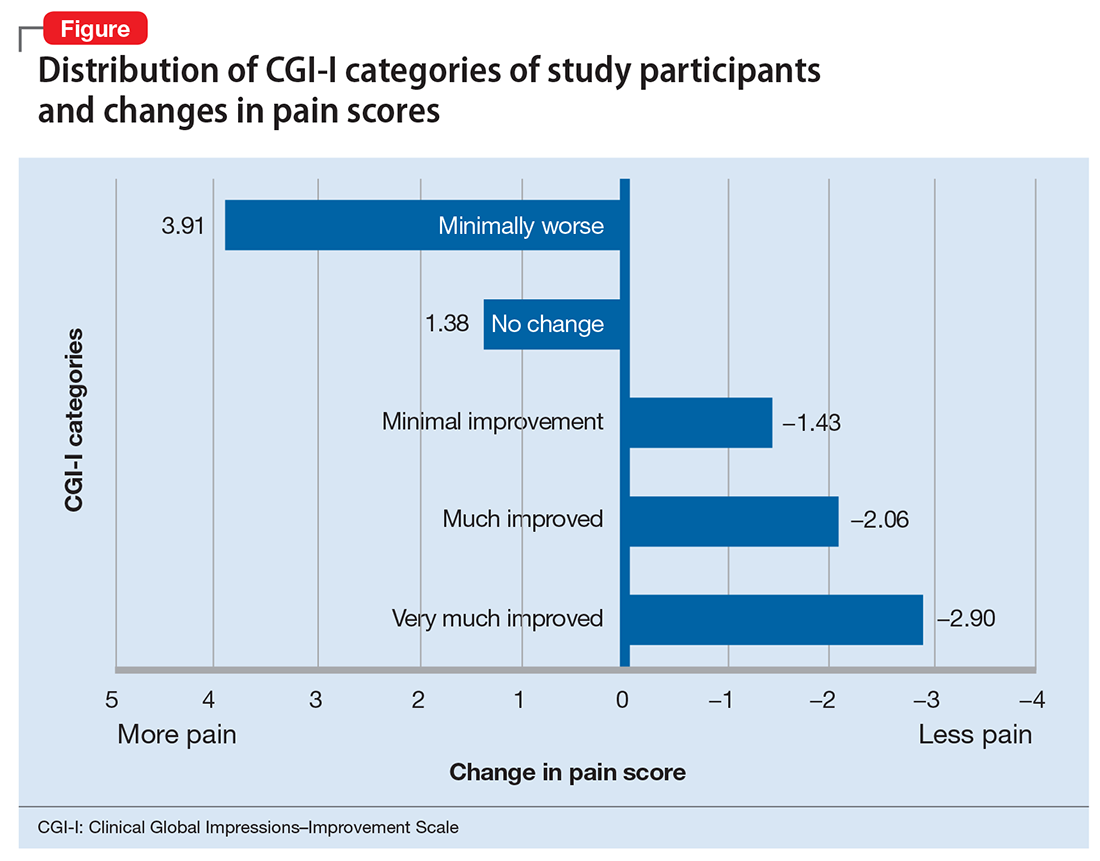

To further characterize the relationship between bipolar disorder and chronic pain, we looked at change in pain scores for mixed, manic, and depressive episodes of bipolar disorder by Clinical Global Impressions—Improvement (CGI-I) Scale categories (Figure). Participants who experienced the greatest clinical improvement also experienced the highest degree of analgesia. Those in the “Very much improved” CGI-I category experienced an almost 3-point decrease in average daily pain scores, with significance well below threshold (P = .0000967; F value = 19.83; F-crit = 4.11). Participants who showed no change in their bipolar I disorder symptoms or experienced exacerbation of their symptoms showed a significant increase in pain scores (P = .037; F value = 6.24; F-crit = 5.32).

Our data show that lithium and carbamazepine provide clinically and statistically significant analgesia in patients with bipolar I disorder and chronic pain. Furthermore, exacerbation of bipolar I disorder symptoms was associated with an increase of approximately 4 points on a 10-point chronic pain scale.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge contributions of Yajie Yu, MD, Sailaja Bysani, MD, Emily Leary, PhD, and Oluwole Popoola, MD, for their work in this study.

1. Vowles KE, McEntee ML, Julnes PS, et al. Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: a systematic review and data synthesis. Pain. 2015;156(4):569-576.

2. Muhuri PK, Gfroerer JC, Davies MC. Associations of nonmedical pain reliever use and initiation of heroin use in the United States. CBHSQ Data Rev. 2013.

3. National Institutes of Health. Department of Health and Human Services. Opiate crisis. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids/opioid-crisis. Updated January 2018. Accessed February 5, 2018.

Misuse of prescription opioids has led to a staggering number of patients developing addiction, which the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) have identified as a health care crisis. In the United States, approximately 29% of patients prescribed an opioid misuse it, and approximately 80% of heroin users started with prescription opioids.1,2 The NIH and HHS have outlined 5 priorities to help resolve this crisis:

- Improve access to prevention, treatment, and recovery support services

- Increase availability and distribution of overdose-reversing medications

- As the epidemic changes, strengthen what we know with improved public health surveillance

- Support research that advances the understanding of pain and addiction and that develops new treatments and interventions

- Improve pain management by utilizing evidence-based practices and reducing opioid misuse and opiate-related harm.3

Treating chronic pain in patients with bipolar disorder

At the Missouri University Psychiatric Center, an inpatient psychiatric ward, we recently conducted a retrospective cohort study to identify effective alternatives for treating pain, and to decrease opioid-related harm. Our study focused on 73 inpatients experiencing exacerbation of bipolar I disorder who also had chronic pain. These patients were treated with mood stabilizers, including lithium and carbamazepine. Patients also were taking medications, as needed, for agitation and their home medications for various medical problems. Selection of mood stabilizer therapy was non-random by standard of care based on best clinical practices. Dosing was based on blood-level monitoring adjusted to maintain therapeutic levels while receiving inpatient care. The average duration of inpatient treatment was approximately 1 to 5 weeks.

Pain was measured at baseline and compared with daily pain scores after mood stabilizer therapy using a 10-point scale, with 0 for no pain to 10 for worse pain, for the duration of the admission As expected based on the findings of previous research, carbamazepine resulted in a decrease in average daily pain score by 1.25 points after treatment (P = .048; F value = 4.3; F-crit = 4.23; calculated by one-way analysis of variance). However, patients who received lithium experienced a greater decrease in average daily pain score, by 2.17 points after treatment (P = .00035; F value = 14.56; F-crit = 4.02).

To further characterize the relationship between bipolar disorder and chronic pain, we looked at change in pain scores for mixed, manic, and depressive episodes of bipolar disorder by Clinical Global Impressions—Improvement (CGI-I) Scale categories (Figure). Participants who experienced the greatest clinical improvement also experienced the highest degree of analgesia. Those in the “Very much improved” CGI-I category experienced an almost 3-point decrease in average daily pain scores, with significance well below threshold (P = .0000967; F value = 19.83; F-crit = 4.11). Participants who showed no change in their bipolar I disorder symptoms or experienced exacerbation of their symptoms showed a significant increase in pain scores (P = .037; F value = 6.24; F-crit = 5.32).

Our data show that lithium and carbamazepine provide clinically and statistically significant analgesia in patients with bipolar I disorder and chronic pain. Furthermore, exacerbation of bipolar I disorder symptoms was associated with an increase of approximately 4 points on a 10-point chronic pain scale.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge contributions of Yajie Yu, MD, Sailaja Bysani, MD, Emily Leary, PhD, and Oluwole Popoola, MD, for their work in this study.

Misuse of prescription opioids has led to a staggering number of patients developing addiction, which the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) have identified as a health care crisis. In the United States, approximately 29% of patients prescribed an opioid misuse it, and approximately 80% of heroin users started with prescription opioids.1,2 The NIH and HHS have outlined 5 priorities to help resolve this crisis:

- Improve access to prevention, treatment, and recovery support services

- Increase availability and distribution of overdose-reversing medications

- As the epidemic changes, strengthen what we know with improved public health surveillance

- Support research that advances the understanding of pain and addiction and that develops new treatments and interventions

- Improve pain management by utilizing evidence-based practices and reducing opioid misuse and opiate-related harm.3

Treating chronic pain in patients with bipolar disorder

At the Missouri University Psychiatric Center, an inpatient psychiatric ward, we recently conducted a retrospective cohort study to identify effective alternatives for treating pain, and to decrease opioid-related harm. Our study focused on 73 inpatients experiencing exacerbation of bipolar I disorder who also had chronic pain. These patients were treated with mood stabilizers, including lithium and carbamazepine. Patients also were taking medications, as needed, for agitation and their home medications for various medical problems. Selection of mood stabilizer therapy was non-random by standard of care based on best clinical practices. Dosing was based on blood-level monitoring adjusted to maintain therapeutic levels while receiving inpatient care. The average duration of inpatient treatment was approximately 1 to 5 weeks.

Pain was measured at baseline and compared with daily pain scores after mood stabilizer therapy using a 10-point scale, with 0 for no pain to 10 for worse pain, for the duration of the admission As expected based on the findings of previous research, carbamazepine resulted in a decrease in average daily pain score by 1.25 points after treatment (P = .048; F value = 4.3; F-crit = 4.23; calculated by one-way analysis of variance). However, patients who received lithium experienced a greater decrease in average daily pain score, by 2.17 points after treatment (P = .00035; F value = 14.56; F-crit = 4.02).

To further characterize the relationship between bipolar disorder and chronic pain, we looked at change in pain scores for mixed, manic, and depressive episodes of bipolar disorder by Clinical Global Impressions—Improvement (CGI-I) Scale categories (Figure). Participants who experienced the greatest clinical improvement also experienced the highest degree of analgesia. Those in the “Very much improved” CGI-I category experienced an almost 3-point decrease in average daily pain scores, with significance well below threshold (P = .0000967; F value = 19.83; F-crit = 4.11). Participants who showed no change in their bipolar I disorder symptoms or experienced exacerbation of their symptoms showed a significant increase in pain scores (P = .037; F value = 6.24; F-crit = 5.32).

Our data show that lithium and carbamazepine provide clinically and statistically significant analgesia in patients with bipolar I disorder and chronic pain. Furthermore, exacerbation of bipolar I disorder symptoms was associated with an increase of approximately 4 points on a 10-point chronic pain scale.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge contributions of Yajie Yu, MD, Sailaja Bysani, MD, Emily Leary, PhD, and Oluwole Popoola, MD, for their work in this study.

1. Vowles KE, McEntee ML, Julnes PS, et al. Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: a systematic review and data synthesis. Pain. 2015;156(4):569-576.

2. Muhuri PK, Gfroerer JC, Davies MC. Associations of nonmedical pain reliever use and initiation of heroin use in the United States. CBHSQ Data Rev. 2013.

3. National Institutes of Health. Department of Health and Human Services. Opiate crisis. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids/opioid-crisis. Updated January 2018. Accessed February 5, 2018.

1. Vowles KE, McEntee ML, Julnes PS, et al. Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: a systematic review and data synthesis. Pain. 2015;156(4):569-576.

2. Muhuri PK, Gfroerer JC, Davies MC. Associations of nonmedical pain reliever use and initiation of heroin use in the United States. CBHSQ Data Rev. 2013.

3. National Institutes of Health. Department of Health and Human Services. Opiate crisis. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids/opioid-crisis. Updated January 2018. Accessed February 5, 2018.

Breast cancer

Manic and nonadherent, with a diagnosis of breast cancer

CASE Diagnosis, mood changes

Ms. A, age 58, is a white female with a history of chronic bipolar I disorder who is being evaluated as a new patient in an academic psychiatric clinic. Recently, she was diagnosed with ER+, PR+, and HER2+ ductal carcinoma. She does not take her prescribed mood stabilizers.

After her cancer diagnosis, Ms. A experiences new-onset agitation, including irritable mood, suicidal thoughts, tearfulness, decreased need for sleep, fast speech, excessive spending, and anorexia. She reports that she hears the voice of God telling her that she could cure her breast cancer through prayer and herbal remedies. Her treatment team, comprising her primary care provider and surgical oncologist, consider several medication adjustments, but are unsure of their effects on Ms. A’s mental health, progression of cancer, and cancer treatment.

What is the most likely cause of Ms. A’s psychiatric symptoms?

a) anxiety from having a diagnosis of cancer

b) stress reaction

c) panic attack

d) manic or mixed phase of bipolar I disorder

The authors’ observations

Treating breast cancer with concurrent severe mental illness is complex and challenging for the patient, family, and health care providers. Mental health and oncology clinicians must collaborate when treating these patients because of overlapping pathophysiology and medication interactions. A comprehensive evaluation is required to tease apart whether a patient is simply demoralized by her new diagnosis, or if a more serious mood disorder is present.

Worldwide, breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer death among women.1 The mean age of women diagnosed with breast cancer is 61 years; 61% of these women are alive 15 years after diagnosis, representing the largest group of female cancer survivors.

The incidence of breast cancer is reported to be higher in women with bipolar disorder compared with the general population.2-4 This positive correlation might be associated with a high rate of smoking, poor health-related behaviors, and, possibly, medication side effects. A genome-wide association study found significant associations between bipolar disorder and the breast cancer-related genes BRCA2 and PALB2.5

Antipsychotics and prolactin

Antipsychotics play an important role in managing bipolar disorder; several, however, are known to raise the serum prolactin level 10- to 20-fold. A high prolactin level could be associated with progression of breast cancer. All antipsychotics have label warnings regarding their use in women with breast cancer.

The prolactin receptor is overexpressed in >95% of breast cancer cells, regardless of estrogen-receptor status. The role of prolactin in development of new breast cancer is open to debate. The effect of a high prolactin level in women with diagnosed breast cancer is unknown, although available preclinical data suggest that high levels should be avoided. Psychiatric clinicians should consider checking the serum prolactin level or switching to a treatment strategy that avoids iatrogenic prolactin elevation. This risk must be carefully weighed against the mood-stabilizing properties of antipsychotics.6

TREATMENT Consider comorbidities

Ms. A receives supportive psychotherapy in addition to quetiapine, 400 mg/d, and valproic acid, 1,500 mg/d. This regimen helps her successfully complete the initial phase of breast cancer treatment, which consists of a single mastectomy, adjuvant chemotherapy (doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel and trastuzumab). She is now on endocrine therapy with tamoxifen.

Ms. A, calm, much improved mood symptoms, and euthymic, has questions regarding her mental health, cancer prognosis, and potential medication side effects with continued cancer treatment.

Which drug used to treat breast cancer might relieve Ms. A’s manic symptoms?

a) cyclophosphamide

b) tamoxifen

c) trastuzumab

d) pamidronate

The authors’ observations

Recent evidence suggests that tamoxifen reduces symptoms of bipolar mania more rapidly than many standard medications for bipolar disorder. Tamoxifen is the only available centrally active protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor,7 although lithium and valproic acid also might inhibit PKC activity. PKC regulates presynaptic and postsynaptic neurotransmission, neuronal excitability, and neurotransmitter release. PKC is thought to be overactive during mania, possibly because of an increase in membrane-bound PKC and PKC translocation from the cytosol to membrane.7,8

Preliminary clinical trials suggest that tamoxifen significantly reduces manic symptoms in patients with bipolar disorder within 5 days of initiation.7 These findings have been confirmed in animal studies and in 1 single-blind and 4 double-blind placebo-controlled clinical studies over the past 15 years.9

Tamoxifen is a selective estrogen-receptor modulator used to prevent recurrence in receptor-positive breast cancer. Cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 is the principal enzyme that converts tamoxifen to its active metabolite, endoxifen. Inhibition of tamoxifen conversion to endoxifen by CYP2D6 inhibitors could decrease the efficacy of tamoxifen therapy and might increase the risk of breast cancer recurrence. Although antidepressants generally are not recommended as a first-line agent for bipolar disorder, several selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors are potent, moderate, or mild inhibitors of CYP2D610 (Table 1). Approximately 7% of women have nonfunctional CYP2D6 alleles and have a lower endoxifen level.11

Treating breast cancer

The mainstays of breast cancer treatment are surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and targeted monoclonal antibody therapy. The protocol of choice depends on the stage of cancer, estrogen receptor status, expression of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2), treatment history, and the patient’s menopausal status. Overexpression of HER-2 oncoprotein, found in 25% to 30% of breast cancers, has been shown to promote cell transformation. HER-2 overexpression is associated with aggressive tumor phenotypes, lymph node involvement, and resistance to chemotherapy and endocrine therapy. Therefore, the HER-2 oncoprotein is a key target for treatment. Often, several therapies are combined to prevent recurrence of disease.

Breast cancer treatment often can cause demoralization, menopausal symptoms, sleep disturbance, impaired sexual function, infertility, and disturbed body image. It also can trigger psychiatric symptoms in patients with, or without, a history of mental illness.

Trastuzumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody against HER-2, and is approved for treating HER-2 positive breast cancer. However, approximately 50% of patients with HER-2 overexpression do not respond to trastuzumab alone or combined with chemotherapy, and nearly all patients develop resistance to trastuzumab, leading to recurrence.12 This medication is still used in practice, and research regarding antiepileptic drugs working in synergy with this monoclonal antibody is underway.

OUTCOME Stability achieved

Quetiapine and valproic acid are first-line choices for Ms. A because (1) she would be on long-term tamoxifen to maintain cancer remission maintenance and (2) she is in a manic phase of bipolar disorder. Tamoxifen also could improve her manic symptoms. This medication regimen might enhance the action of cancer treatments and also could reduce adverse effects of cancer treatment, such as insomnia associated with tamoxifen.

After the team educates Ms. A about how her psychiatric medications could benefit her cancer treatment, she becomes more motivated to stay on her regimen. Ms. A does well on these medications and after 18 months has not experienced exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms or recurrence of cancer.

The authors’ observations

There are 3 major classes of mood stabilizers for treating bipolar disorder: lithium, antiepileptic drugs, and atypical antipsychotics.13 In a setting of cancer, mood stabilizers are prescribed for managing mania or drug-induced agitation or anxiety associated with steroid use, brain metastases, and other medical conditions. They also can be used to treat neuropathic pain and hot flashes and seizure prophylaxis.13

Valproic acid

Valproic acid can help treat mood lability, impulsivity, and disinhibition, whether these symptoms are due to primary psychiatric illness or secondary to cancer metastasis. It is a first-line agent for manic and mixed bipolar states, and can be titrated quickly to achieve optimal benefit. Valproic acid also has been described as a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, known to attenuate apoptotic activity, making it of interest as a treatment for cancer.14 HDAC inhibitors have been shown to:

- induce differentiation and cell cycle arrest

- activate the extrinsic or intrinsic pathways of apoptosis

- inhibit invasion, migration, and angiogenesis in different cancer cell lines.15

In regard to breast cancer, valproic acid inhibits growth of cell lines independent of estrogen receptors, increases the action of such breast cancer treatments as tamoxifen, raloxifene, fulvestrant, and letrozole, and induces solid tumor regression.14 Valproic acid also reduces cancer cell viability and could act as a powerful antiproliferative agent in estrogen-sensitive breast cancer cells.16

Valproic acid reduces cell growth-inducing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in ERα-positive breast cancer cells, although it has no significant apoptotic effect in ERα-negative cells.16 However, evidence does support the ability of valproic acid to restore an estrogen-sensitive phenotype in ERα-negative breast cancer cells, allowing successful treatment with the anti-estrogen tamoxifen in vitro.10

Antipsychotics

Antipsychotics act as dopamine D2 receptor antagonists within the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, thus increasing the serum prolactin level. Among atypicals, risperidone and its active metabolite, paliperidone, produce the greatest increase in the prolactin level, whereas quetiapine, clozapine, and aripiprazole minimally elevate the prolactin level.

Hyperprolactinemia correlates with rapid breast cancer progression and inferior prognosis, regardless of breast cancer receptor typing. Therefore, prolactin-sparing antipsychotics are preferred when treating a patient with comorbid bipolar disorder and breast cancer. Checking the serum prolactin level might help guide treatment. The literature is mixed regarding antipsychotic use and new mammary tumorigenesis; current research does not support antipsychotic choice based on future risk of breast cancer.6

Other adverse effects from antipsychotic use for bipolar disorder could have an impact on patients with breast cancer. Several of these medications could ameliorate side effects of advanced cancer and chemotherapy. Quetiapine, for example, might improve tamoxifen-induced insomnia in women with breast cancer because of its high affinity for serotonergic receptors, thus enhancing central serotonergic neurotransmitters and decreasing excitatory glutamatergic transmission.17

In any type of advanced cancer, nausea and vomiting are common, independent of chemotherapy and medication regimens. Metabolic derangement, vestibular dysfunction, CNS disorders, and visceral metastasis all contribute to hyperemesis. Olanzapine has been shown to significantly reduce refractory nausea and can cause weight gain and improved appetite, which benefits cachectic patients.18

Last, clozapine is one of the more effective antipsychotic medications, but also carries a risk of neutropenia. In patients with neutropenia secondary to chemotherapy, clozapine could increase the risk of infection in an immunocompromised patient.19 Granulocyte colony stimulating factor might be useful as a rescue medication for treatment-emergent neutropenia.19

Treatment considerations

Cancer patients might be unable or unwilling to seek services for mental health during their cancer treatment, and many who have a diagnosis of psychiatric illness might stop following up with psychiatric care when cancer treatment takes priority. It is critical for clinicians to be aware of the current literature regarding the impact of mood-stabilizing medication on cancer treatment. Monitoring for drug interactions is essential, and electronic drug interaction tools, such as Lexicomp, may be useful for this purpose.13 Because of special vulnerabilities in this population, cautious and judicious prescribing practices are advised.

The risk-benefit profile for medications for bipolar disorder must be considered before they are initiated or changes are made to the regimen (Table 2). Changing an effective mood stabilizer to gain benefits in breast cancer prognosis is not recommended in most cases, because benefits have been shown to be only significant in preclinical research; currently, there are no clinical guidelines. However, medication adjustments should be made with these theoretical benefits in mind, as long as the treatment of bipolar disorder remains effective.

Regardless of what treatment regimen the health team decides on, several underlying issues that affect patient care must be considered in this population. Successfully treating breast cancer in a woman with severe mental illness only can be accomplished when her mental illness is under control. Once she is psychiatrically stable, it is important for her to have a basic understanding of how cancer can affect the body and know the reasons behind treatment.

It is imperative that physicians provide their patients with a general understanding of their comorbid disorders, and find ways to help patients remain adherent with treatment of both diseases. Many patients feel demoralized by a cancer diagnosis and adherence to a medication regimen might be a difficult task among those with bipolar disorder who also are socially isolated, lack education, or have poor recall of treatment recommendations.20

Bottom Line

Managing comorbid bipolar disorder and breast cancer might seem daunting,

but treatments for the 2 diseases can work in synergy. You have an opportunity to

educate patients and colleagues in treating bipolar disorder and comorbid breast

cancer. Optimizing care using known psychopharmacologic data can not only lead

to better outcomes, but might additionally offer some hope and reason to remain

treatment-adherent for patients suffering from this complex comorbidity.

Related Resources

• Agarwala P, Riba MB. Tailoring depression treatment for women with breast cancer. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(11): 39-40,45-46,48-49.

• Cunningham R, Sarfati D, Stanley J, et al. Cancer survival in the context of mental illness: a national cohort study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37(6):501-506.

Drug Brand Names

Amiodarone • Cordarone

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Asenapine • Saphris

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Citalopram • Celexa

Clozapine • Clozaril

Cyclophosphamide • Cytoxan, Neosar

Doxorubicin • Doxil, Adriamycin

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fulvestrant • Faslodex

Iloperidone • Fanapt

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Letrozole • Femara

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paclitaxel • Onxol

Paliperidone • Invega

Pamidronate • Aredia

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Raloxifene • Evista

Risperidone • Risperdal

Sertraline • Zoloft

Tamoxifen • Nolvadex

Thioridazine • Mellaril

Trastuzumab • Herceptin

Valproic acid • Depakene

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69-90.

2. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2014. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2014.

3. BarChana M, Levav I, Lipshitz I, et al. Enhanced cancer risk among patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2008;108(1-2):43-48.

4. Hung YP, Liu CJ, Tsai CF, et al. Incidence and risk of mood disorders in patients with breast cancers in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based study. Psychooncology. 2013;22(10):2227-2234.

5. Tesli M, Athanasiu L, Mattingsdal M, et al. Association analysis of PALB2 and BRCA2 in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia in a scandinavian case–control sample. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153B(7):1276-1282.

6. Rahman T, Clevenger CV, Kaklamani V, et al. Antipsychotic treatment in breast cancer patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(6):616-621.

7. Armani F, Andersen ML, Galduróz JC. Tamoxifen use for the management of mania: a review of current preclinical evidence. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014;231(4):639-649.

8. Zarate CA Jr, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, et al. Efficacy of a protein kinase C inhibitor (tamoxifen) in the treatment of acute mania: a pilot study. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(6):561-570.

9. Zarate CA, Manji HK. Protein kinase C inhibitors: rationale for use and potential in the treatment of bipolar disorder. CNS Drugs. 2009;23(7):569-582.

10. Fortunati N, Bertino S, Costantino L, et al. Valproic acid restores ER alpha and antiestrogen sensitivity to ER alpha-negative breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;314(1):17-22.

11. Thekdi SM, Trinidad A, Roth A. Psychopharmacology in cancer. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2014;17(1):529.

12. Meng Q, Chen X, Sun L, et al. Carbamazepine promotes Her-2 protein degradation in breast cancer cells by modulating HDAC6 activity and acetylation of Hsp90. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;348(1-2):165-171.

13. Altamura AC, Lietti L, Dobrea C, et al. Mood stabilizers for patients with bipolar disorder: the state of the art. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(1):85-99.

14. Chateauvieux S, Morceau F, Dicato M, et al. Molecular and therapeutic potential and toxicity of valproic acid [published online July 29, 2010]. J Biomed Biotechnol. doi: 10.1155/2010/479364.

15. Jafary H, Ahmadian S, Soleimani M. The enhanced apoptosis and antiproliferative response to combined treatment with valproate and nicotinamide in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 2013;35(3):2701-2710.

16. Fortunati N, Bertino S, Costantino L, et al. Valproic acid is a selective antiproliferative agent in estrogen-sensitive breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2008;259(2):156-164.

17. Pasquini M, Speca A, Biondi M. Quetiapine for tamoxifen-induced insomnia in women with breast cancer. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(2):159-161.

18. Srivastava M, Brito-Dellan N, Davis MP, et al. Olanzapine as an antiemetic in refractory nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25(6):578-582.

19. Sankaranarayanan A, Mulchandani M, Tirupati S. Clozapine, cancer chemotherapy and neutropenia - dilemmas in management. Psychiatr Danub. 2013;25(4):419-422.

20. Cole M, Padmanabhan A. Breast cancer treatment of women with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder from Philadelphia, PA: lessons learned and suggestions for improvement. J Cancer Educ. 2012;27(4):774-779.

CASE Diagnosis, mood changes

Ms. A, age 58, is a white female with a history of chronic bipolar I disorder who is being evaluated as a new patient in an academic psychiatric clinic. Recently, she was diagnosed with ER+, PR+, and HER2+ ductal carcinoma. She does not take her prescribed mood stabilizers.

After her cancer diagnosis, Ms. A experiences new-onset agitation, including irritable mood, suicidal thoughts, tearfulness, decreased need for sleep, fast speech, excessive spending, and anorexia. She reports that she hears the voice of God telling her that she could cure her breast cancer through prayer and herbal remedies. Her treatment team, comprising her primary care provider and surgical oncologist, consider several medication adjustments, but are unsure of their effects on Ms. A’s mental health, progression of cancer, and cancer treatment.

What is the most likely cause of Ms. A’s psychiatric symptoms?

a) anxiety from having a diagnosis of cancer

b) stress reaction

c) panic attack

d) manic or mixed phase of bipolar I disorder

The authors’ observations

Treating breast cancer with concurrent severe mental illness is complex and challenging for the patient, family, and health care providers. Mental health and oncology clinicians must collaborate when treating these patients because of overlapping pathophysiology and medication interactions. A comprehensive evaluation is required to tease apart whether a patient is simply demoralized by her new diagnosis, or if a more serious mood disorder is present.

Worldwide, breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer death among women.1 The mean age of women diagnosed with breast cancer is 61 years; 61% of these women are alive 15 years after diagnosis, representing the largest group of female cancer survivors.

The incidence of breast cancer is reported to be higher in women with bipolar disorder compared with the general population.2-4 This positive correlation might be associated with a high rate of smoking, poor health-related behaviors, and, possibly, medication side effects. A genome-wide association study found significant associations between bipolar disorder and the breast cancer-related genes BRCA2 and PALB2.5

Antipsychotics and prolactin

Antipsychotics play an important role in managing bipolar disorder; several, however, are known to raise the serum prolactin level 10- to 20-fold. A high prolactin level could be associated with progression of breast cancer. All antipsychotics have label warnings regarding their use in women with breast cancer.

The prolactin receptor is overexpressed in >95% of breast cancer cells, regardless of estrogen-receptor status. The role of prolactin in development of new breast cancer is open to debate. The effect of a high prolactin level in women with diagnosed breast cancer is unknown, although available preclinical data suggest that high levels should be avoided. Psychiatric clinicians should consider checking the serum prolactin level or switching to a treatment strategy that avoids iatrogenic prolactin elevation. This risk must be carefully weighed against the mood-stabilizing properties of antipsychotics.6

TREATMENT Consider comorbidities

Ms. A receives supportive psychotherapy in addition to quetiapine, 400 mg/d, and valproic acid, 1,500 mg/d. This regimen helps her successfully complete the initial phase of breast cancer treatment, which consists of a single mastectomy, adjuvant chemotherapy (doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel and trastuzumab). She is now on endocrine therapy with tamoxifen.

Ms. A, calm, much improved mood symptoms, and euthymic, has questions regarding her mental health, cancer prognosis, and potential medication side effects with continued cancer treatment.

Which drug used to treat breast cancer might relieve Ms. A’s manic symptoms?

a) cyclophosphamide

b) tamoxifen

c) trastuzumab

d) pamidronate

The authors’ observations

Recent evidence suggests that tamoxifen reduces symptoms of bipolar mania more rapidly than many standard medications for bipolar disorder. Tamoxifen is the only available centrally active protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor,7 although lithium and valproic acid also might inhibit PKC activity. PKC regulates presynaptic and postsynaptic neurotransmission, neuronal excitability, and neurotransmitter release. PKC is thought to be overactive during mania, possibly because of an increase in membrane-bound PKC and PKC translocation from the cytosol to membrane.7,8

Preliminary clinical trials suggest that tamoxifen significantly reduces manic symptoms in patients with bipolar disorder within 5 days of initiation.7 These findings have been confirmed in animal studies and in 1 single-blind and 4 double-blind placebo-controlled clinical studies over the past 15 years.9

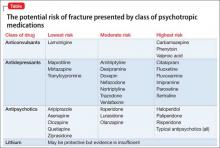

Tamoxifen is a selective estrogen-receptor modulator used to prevent recurrence in receptor-positive breast cancer. Cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 is the principal enzyme that converts tamoxifen to its active metabolite, endoxifen. Inhibition of tamoxifen conversion to endoxifen by CYP2D6 inhibitors could decrease the efficacy of tamoxifen therapy and might increase the risk of breast cancer recurrence. Although antidepressants generally are not recommended as a first-line agent for bipolar disorder, several selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors are potent, moderate, or mild inhibitors of CYP2D610 (Table 1). Approximately 7% of women have nonfunctional CYP2D6 alleles and have a lower endoxifen level.11

Treating breast cancer

The mainstays of breast cancer treatment are surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and targeted monoclonal antibody therapy. The protocol of choice depends on the stage of cancer, estrogen receptor status, expression of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2), treatment history, and the patient’s menopausal status. Overexpression of HER-2 oncoprotein, found in 25% to 30% of breast cancers, has been shown to promote cell transformation. HER-2 overexpression is associated with aggressive tumor phenotypes, lymph node involvement, and resistance to chemotherapy and endocrine therapy. Therefore, the HER-2 oncoprotein is a key target for treatment. Often, several therapies are combined to prevent recurrence of disease.

Breast cancer treatment often can cause demoralization, menopausal symptoms, sleep disturbance, impaired sexual function, infertility, and disturbed body image. It also can trigger psychiatric symptoms in patients with, or without, a history of mental illness.

Trastuzumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody against HER-2, and is approved for treating HER-2 positive breast cancer. However, approximately 50% of patients with HER-2 overexpression do not respond to trastuzumab alone or combined with chemotherapy, and nearly all patients develop resistance to trastuzumab, leading to recurrence.12 This medication is still used in practice, and research regarding antiepileptic drugs working in synergy with this monoclonal antibody is underway.

OUTCOME Stability achieved

Quetiapine and valproic acid are first-line choices for Ms. A because (1) she would be on long-term tamoxifen to maintain cancer remission maintenance and (2) she is in a manic phase of bipolar disorder. Tamoxifen also could improve her manic symptoms. This medication regimen might enhance the action of cancer treatments and also could reduce adverse effects of cancer treatment, such as insomnia associated with tamoxifen.

After the team educates Ms. A about how her psychiatric medications could benefit her cancer treatment, she becomes more motivated to stay on her regimen. Ms. A does well on these medications and after 18 months has not experienced exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms or recurrence of cancer.

The authors’ observations

There are 3 major classes of mood stabilizers for treating bipolar disorder: lithium, antiepileptic drugs, and atypical antipsychotics.13 In a setting of cancer, mood stabilizers are prescribed for managing mania or drug-induced agitation or anxiety associated with steroid use, brain metastases, and other medical conditions. They also can be used to treat neuropathic pain and hot flashes and seizure prophylaxis.13

Valproic acid

Valproic acid can help treat mood lability, impulsivity, and disinhibition, whether these symptoms are due to primary psychiatric illness or secondary to cancer metastasis. It is a first-line agent for manic and mixed bipolar states, and can be titrated quickly to achieve optimal benefit. Valproic acid also has been described as a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, known to attenuate apoptotic activity, making it of interest as a treatment for cancer.14 HDAC inhibitors have been shown to:

- induce differentiation and cell cycle arrest

- activate the extrinsic or intrinsic pathways of apoptosis

- inhibit invasion, migration, and angiogenesis in different cancer cell lines.15

In regard to breast cancer, valproic acid inhibits growth of cell lines independent of estrogen receptors, increases the action of such breast cancer treatments as tamoxifen, raloxifene, fulvestrant, and letrozole, and induces solid tumor regression.14 Valproic acid also reduces cancer cell viability and could act as a powerful antiproliferative agent in estrogen-sensitive breast cancer cells.16

Valproic acid reduces cell growth-inducing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in ERα-positive breast cancer cells, although it has no significant apoptotic effect in ERα-negative cells.16 However, evidence does support the ability of valproic acid to restore an estrogen-sensitive phenotype in ERα-negative breast cancer cells, allowing successful treatment with the anti-estrogen tamoxifen in vitro.10

Antipsychotics

Antipsychotics act as dopamine D2 receptor antagonists within the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, thus increasing the serum prolactin level. Among atypicals, risperidone and its active metabolite, paliperidone, produce the greatest increase in the prolactin level, whereas quetiapine, clozapine, and aripiprazole minimally elevate the prolactin level.

Hyperprolactinemia correlates with rapid breast cancer progression and inferior prognosis, regardless of breast cancer receptor typing. Therefore, prolactin-sparing antipsychotics are preferred when treating a patient with comorbid bipolar disorder and breast cancer. Checking the serum prolactin level might help guide treatment. The literature is mixed regarding antipsychotic use and new mammary tumorigenesis; current research does not support antipsychotic choice based on future risk of breast cancer.6

Other adverse effects from antipsychotic use for bipolar disorder could have an impact on patients with breast cancer. Several of these medications could ameliorate side effects of advanced cancer and chemotherapy. Quetiapine, for example, might improve tamoxifen-induced insomnia in women with breast cancer because of its high affinity for serotonergic receptors, thus enhancing central serotonergic neurotransmitters and decreasing excitatory glutamatergic transmission.17

In any type of advanced cancer, nausea and vomiting are common, independent of chemotherapy and medication regimens. Metabolic derangement, vestibular dysfunction, CNS disorders, and visceral metastasis all contribute to hyperemesis. Olanzapine has been shown to significantly reduce refractory nausea and can cause weight gain and improved appetite, which benefits cachectic patients.18

Last, clozapine is one of the more effective antipsychotic medications, but also carries a risk of neutropenia. In patients with neutropenia secondary to chemotherapy, clozapine could increase the risk of infection in an immunocompromised patient.19 Granulocyte colony stimulating factor might be useful as a rescue medication for treatment-emergent neutropenia.19

Treatment considerations

Cancer patients might be unable or unwilling to seek services for mental health during their cancer treatment, and many who have a diagnosis of psychiatric illness might stop following up with psychiatric care when cancer treatment takes priority. It is critical for clinicians to be aware of the current literature regarding the impact of mood-stabilizing medication on cancer treatment. Monitoring for drug interactions is essential, and electronic drug interaction tools, such as Lexicomp, may be useful for this purpose.13 Because of special vulnerabilities in this population, cautious and judicious prescribing practices are advised.

The risk-benefit profile for medications for bipolar disorder must be considered before they are initiated or changes are made to the regimen (Table 2). Changing an effective mood stabilizer to gain benefits in breast cancer prognosis is not recommended in most cases, because benefits have been shown to be only significant in preclinical research; currently, there are no clinical guidelines. However, medication adjustments should be made with these theoretical benefits in mind, as long as the treatment of bipolar disorder remains effective.

Regardless of what treatment regimen the health team decides on, several underlying issues that affect patient care must be considered in this population. Successfully treating breast cancer in a woman with severe mental illness only can be accomplished when her mental illness is under control. Once she is psychiatrically stable, it is important for her to have a basic understanding of how cancer can affect the body and know the reasons behind treatment.

It is imperative that physicians provide their patients with a general understanding of their comorbid disorders, and find ways to help patients remain adherent with treatment of both diseases. Many patients feel demoralized by a cancer diagnosis and adherence to a medication regimen might be a difficult task among those with bipolar disorder who also are socially isolated, lack education, or have poor recall of treatment recommendations.20

Bottom Line

Managing comorbid bipolar disorder and breast cancer might seem daunting,

but treatments for the 2 diseases can work in synergy. You have an opportunity to

educate patients and colleagues in treating bipolar disorder and comorbid breast

cancer. Optimizing care using known psychopharmacologic data can not only lead

to better outcomes, but might additionally offer some hope and reason to remain

treatment-adherent for patients suffering from this complex comorbidity.

Related Resources

• Agarwala P, Riba MB. Tailoring depression treatment for women with breast cancer. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(11): 39-40,45-46,48-49.

• Cunningham R, Sarfati D, Stanley J, et al. Cancer survival in the context of mental illness: a national cohort study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37(6):501-506.

Drug Brand Names

Amiodarone • Cordarone

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Asenapine • Saphris

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Citalopram • Celexa

Clozapine • Clozaril

Cyclophosphamide • Cytoxan, Neosar

Doxorubicin • Doxil, Adriamycin

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fulvestrant • Faslodex

Iloperidone • Fanapt

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Letrozole • Femara

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lurasidone • Latuda

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paclitaxel • Onxol

Paliperidone • Invega

Pamidronate • Aredia

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Raloxifene • Evista

Risperidone • Risperdal

Sertraline • Zoloft

Tamoxifen • Nolvadex

Thioridazine • Mellaril

Trastuzumab • Herceptin

Valproic acid • Depakene

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE Diagnosis, mood changes

Ms. A, age 58, is a white female with a history of chronic bipolar I disorder who is being evaluated as a new patient in an academic psychiatric clinic. Recently, she was diagnosed with ER+, PR+, and HER2+ ductal carcinoma. She does not take her prescribed mood stabilizers.

After her cancer diagnosis, Ms. A experiences new-onset agitation, including irritable mood, suicidal thoughts, tearfulness, decreased need for sleep, fast speech, excessive spending, and anorexia. She reports that she hears the voice of God telling her that she could cure her breast cancer through prayer and herbal remedies. Her treatment team, comprising her primary care provider and surgical oncologist, consider several medication adjustments, but are unsure of their effects on Ms. A’s mental health, progression of cancer, and cancer treatment.

What is the most likely cause of Ms. A’s psychiatric symptoms?

a) anxiety from having a diagnosis of cancer

b) stress reaction

c) panic attack

d) manic or mixed phase of bipolar I disorder

The authors’ observations

Treating breast cancer with concurrent severe mental illness is complex and challenging for the patient, family, and health care providers. Mental health and oncology clinicians must collaborate when treating these patients because of overlapping pathophysiology and medication interactions. A comprehensive evaluation is required to tease apart whether a patient is simply demoralized by her new diagnosis, or if a more serious mood disorder is present.

Worldwide, breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer death among women.1 The mean age of women diagnosed with breast cancer is 61 years; 61% of these women are alive 15 years after diagnosis, representing the largest group of female cancer survivors.

The incidence of breast cancer is reported to be higher in women with bipolar disorder compared with the general population.2-4 This positive correlation might be associated with a high rate of smoking, poor health-related behaviors, and, possibly, medication side effects. A genome-wide association study found significant associations between bipolar disorder and the breast cancer-related genes BRCA2 and PALB2.5

Antipsychotics and prolactin

Antipsychotics play an important role in managing bipolar disorder; several, however, are known to raise the serum prolactin level 10- to 20-fold. A high prolactin level could be associated with progression of breast cancer. All antipsychotics have label warnings regarding their use in women with breast cancer.

The prolactin receptor is overexpressed in >95% of breast cancer cells, regardless of estrogen-receptor status. The role of prolactin in development of new breast cancer is open to debate. The effect of a high prolactin level in women with diagnosed breast cancer is unknown, although available preclinical data suggest that high levels should be avoided. Psychiatric clinicians should consider checking the serum prolactin level or switching to a treatment strategy that avoids iatrogenic prolactin elevation. This risk must be carefully weighed against the mood-stabilizing properties of antipsychotics.6

TREATMENT Consider comorbidities

Ms. A receives supportive psychotherapy in addition to quetiapine, 400 mg/d, and valproic acid, 1,500 mg/d. This regimen helps her successfully complete the initial phase of breast cancer treatment, which consists of a single mastectomy, adjuvant chemotherapy (doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by paclitaxel and trastuzumab). She is now on endocrine therapy with tamoxifen.

Ms. A, calm, much improved mood symptoms, and euthymic, has questions regarding her mental health, cancer prognosis, and potential medication side effects with continued cancer treatment.

Which drug used to treat breast cancer might relieve Ms. A’s manic symptoms?

a) cyclophosphamide

b) tamoxifen

c) trastuzumab

d) pamidronate

The authors’ observations

Recent evidence suggests that tamoxifen reduces symptoms of bipolar mania more rapidly than many standard medications for bipolar disorder. Tamoxifen is the only available centrally active protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor,7 although lithium and valproic acid also might inhibit PKC activity. PKC regulates presynaptic and postsynaptic neurotransmission, neuronal excitability, and neurotransmitter release. PKC is thought to be overactive during mania, possibly because of an increase in membrane-bound PKC and PKC translocation from the cytosol to membrane.7,8

Preliminary clinical trials suggest that tamoxifen significantly reduces manic symptoms in patients with bipolar disorder within 5 days of initiation.7 These findings have been confirmed in animal studies and in 1 single-blind and 4 double-blind placebo-controlled clinical studies over the past 15 years.9

Tamoxifen is a selective estrogen-receptor modulator used to prevent recurrence in receptor-positive breast cancer. Cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 is the principal enzyme that converts tamoxifen to its active metabolite, endoxifen. Inhibition of tamoxifen conversion to endoxifen by CYP2D6 inhibitors could decrease the efficacy of tamoxifen therapy and might increase the risk of breast cancer recurrence. Although antidepressants generally are not recommended as a first-line agent for bipolar disorder, several selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors are potent, moderate, or mild inhibitors of CYP2D610 (Table 1). Approximately 7% of women have nonfunctional CYP2D6 alleles and have a lower endoxifen level.11

Treating breast cancer

The mainstays of breast cancer treatment are surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, and targeted monoclonal antibody therapy. The protocol of choice depends on the stage of cancer, estrogen receptor status, expression of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2), treatment history, and the patient’s menopausal status. Overexpression of HER-2 oncoprotein, found in 25% to 30% of breast cancers, has been shown to promote cell transformation. HER-2 overexpression is associated with aggressive tumor phenotypes, lymph node involvement, and resistance to chemotherapy and endocrine therapy. Therefore, the HER-2 oncoprotein is a key target for treatment. Often, several therapies are combined to prevent recurrence of disease.

Breast cancer treatment often can cause demoralization, menopausal symptoms, sleep disturbance, impaired sexual function, infertility, and disturbed body image. It also can trigger psychiatric symptoms in patients with, or without, a history of mental illness.

Trastuzumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody against HER-2, and is approved for treating HER-2 positive breast cancer. However, approximately 50% of patients with HER-2 overexpression do not respond to trastuzumab alone or combined with chemotherapy, and nearly all patients develop resistance to trastuzumab, leading to recurrence.12 This medication is still used in practice, and research regarding antiepileptic drugs working in synergy with this monoclonal antibody is underway.

OUTCOME Stability achieved

Quetiapine and valproic acid are first-line choices for Ms. A because (1) she would be on long-term tamoxifen to maintain cancer remission maintenance and (2) she is in a manic phase of bipolar disorder. Tamoxifen also could improve her manic symptoms. This medication regimen might enhance the action of cancer treatments and also could reduce adverse effects of cancer treatment, such as insomnia associated with tamoxifen.

After the team educates Ms. A about how her psychiatric medications could benefit her cancer treatment, she becomes more motivated to stay on her regimen. Ms. A does well on these medications and after 18 months has not experienced exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms or recurrence of cancer.

The authors’ observations

There are 3 major classes of mood stabilizers for treating bipolar disorder: lithium, antiepileptic drugs, and atypical antipsychotics.13 In a setting of cancer, mood stabilizers are prescribed for managing mania or drug-induced agitation or anxiety associated with steroid use, brain metastases, and other medical conditions. They also can be used to treat neuropathic pain and hot flashes and seizure prophylaxis.13

Valproic acid

Valproic acid can help treat mood lability, impulsivity, and disinhibition, whether these symptoms are due to primary psychiatric illness or secondary to cancer metastasis. It is a first-line agent for manic and mixed bipolar states, and can be titrated quickly to achieve optimal benefit. Valproic acid also has been described as a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, known to attenuate apoptotic activity, making it of interest as a treatment for cancer.14 HDAC inhibitors have been shown to:

- induce differentiation and cell cycle arrest

- activate the extrinsic or intrinsic pathways of apoptosis

- inhibit invasion, migration, and angiogenesis in different cancer cell lines.15

In regard to breast cancer, valproic acid inhibits growth of cell lines independent of estrogen receptors, increases the action of such breast cancer treatments as tamoxifen, raloxifene, fulvestrant, and letrozole, and induces solid tumor regression.14 Valproic acid also reduces cancer cell viability and could act as a powerful antiproliferative agent in estrogen-sensitive breast cancer cells.16

Valproic acid reduces cell growth-inducing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in ERα-positive breast cancer cells, although it has no significant apoptotic effect in ERα-negative cells.16 However, evidence does support the ability of valproic acid to restore an estrogen-sensitive phenotype in ERα-negative breast cancer cells, allowing successful treatment with the anti-estrogen tamoxifen in vitro.10

Antipsychotics

Antipsychotics act as dopamine D2 receptor antagonists within the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, thus increasing the serum prolactin level. Among atypicals, risperidone and its active metabolite, paliperidone, produce the greatest increase in the prolactin level, whereas quetiapine, clozapine, and aripiprazole minimally elevate the prolactin level.

Hyperprolactinemia correlates with rapid breast cancer progression and inferior prognosis, regardless of breast cancer receptor typing. Therefore, prolactin-sparing antipsychotics are preferred when treating a patient with comorbid bipolar disorder and breast cancer. Checking the serum prolactin level might help guide treatment. The literature is mixed regarding antipsychotic use and new mammary tumorigenesis; current research does not support antipsychotic choice based on future risk of breast cancer.6

Other adverse effects from antipsychotic use for bipolar disorder could have an impact on patients with breast cancer. Several of these medications could ameliorate side effects of advanced cancer and chemotherapy. Quetiapine, for example, might improve tamoxifen-induced insomnia in women with breast cancer because of its high affinity for serotonergic receptors, thus enhancing central serotonergic neurotransmitters and decreasing excitatory glutamatergic transmission.17

In any type of advanced cancer, nausea and vomiting are common, independent of chemotherapy and medication regimens. Metabolic derangement, vestibular dysfunction, CNS disorders, and visceral metastasis all contribute to hyperemesis. Olanzapine has been shown to significantly reduce refractory nausea and can cause weight gain and improved appetite, which benefits cachectic patients.18

Last, clozapine is one of the more effective antipsychotic medications, but also carries a risk of neutropenia. In patients with neutropenia secondary to chemotherapy, clozapine could increase the risk of infection in an immunocompromised patient.19 Granulocyte colony stimulating factor might be useful as a rescue medication for treatment-emergent neutropenia.19

Treatment considerations

Cancer patients might be unable or unwilling to seek services for mental health during their cancer treatment, and many who have a diagnosis of psychiatric illness might stop following up with psychiatric care when cancer treatment takes priority. It is critical for clinicians to be aware of the current literature regarding the impact of mood-stabilizing medication on cancer treatment. Monitoring for drug interactions is essential, and electronic drug interaction tools, such as Lexicomp, may be useful for this purpose.13 Because of special vulnerabilities in this population, cautious and judicious prescribing practices are advised.

The risk-benefit profile for medications for bipolar disorder must be considered before they are initiated or changes are made to the regimen (Table 2). Changing an effective mood stabilizer to gain benefits in breast cancer prognosis is not recommended in most cases, because benefits have been shown to be only significant in preclinical research; currently, there are no clinical guidelines. However, medication adjustments should be made with these theoretical benefits in mind, as long as the treatment of bipolar disorder remains effective.

Regardless of what treatment regimen the health team decides on, several underlying issues that affect patient care must be considered in this population. Successfully treating breast cancer in a woman with severe mental illness only can be accomplished when her mental illness is under control. Once she is psychiatrically stable, it is important for her to have a basic understanding of how cancer can affect the body and know the reasons behind treatment.

It is imperative that physicians provide their patients with a general understanding of their comorbid disorders, and find ways to help patients remain adherent with treatment of both diseases. Many patients feel demoralized by a cancer diagnosis and adherence to a medication regimen might be a difficult task among those with bipolar disorder who also are socially isolated, lack education, or have poor recall of treatment recommendations.20

Bottom Line

Managing comorbid bipolar disorder and breast cancer might seem daunting,

but treatments for the 2 diseases can work in synergy. You have an opportunity to

educate patients and colleagues in treating bipolar disorder and comorbid breast

cancer. Optimizing care using known psychopharmacologic data can not only lead

to better outcomes, but might additionally offer some hope and reason to remain

treatment-adherent for patients suffering from this complex comorbidity.

Related Resources

• Agarwala P, Riba MB. Tailoring depression treatment for women with breast cancer. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(11): 39-40,45-46,48-49.

• Cunningham R, Sarfati D, Stanley J, et al. Cancer survival in the context of mental illness: a national cohort study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37(6):501-506.

Drug Brand Names

Amiodarone • Cordarone

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Asenapine • Saphris