User login

How Media Coverage of Oral Minoxidil for Hair Loss Has Impacted Prescribing Habits

Minoxidil, a potent vasodilator, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1963 to treat high blood pressure. Its application as a hair loss treatment was discovered by accident—patients taking oral minoxidil for blood pressure noticed hair growth on their bodies as a side effect of the medication. In 1988, topical minoxidil (Rogaine [Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc]) was approved by the FDA for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men, and then it was approved for the same indication in women in 1991. The mechanism of action by which minoxidil increases hair growth still has not been fully elucidated. When applied topically, it is thought to extend the anagen phase (or growth phase) of the hair cycle and increase hair follicle size. It also increases oxygen to the hair follicle through vasodilation and stimulates the production of vascular endothelial growth factor, which is thought to promote hair growth.1 Since its approval, topical minoxidil has become a first-line treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men and women.

In August 2022, The New York Times (NYT) published an article on dermatologists’ use of oral minoxidil at a fraction of the dose prescribed for blood pressure with profound results in hair regrowth.2 Several dermatologists quoted in the article endorsed that the decreased dose minimizes unwanted side effects such as hypertrichosis, hypotension, and other cardiac issues while still being effective for hair loss. Also, compared to topical minoxidil, low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) is relatively cheaper and easier to use; topicals are more cumbersome to apply and often leave the hair and scalp sticky, leading to noncompliance among patients.2 Currently, oral minoxidil is not approved by the FDA for use in hair loss, making it an off-label use.

Since the NYT article was published, we have observed an increase in patient questions and requests for LDOM as well as heightened use by fellow dermatologists in our community. As of November 2022, the NYT had approximately 9,330,000 total subscribers, solidifying its place as a newspaper of record in the United States and across the world.3 In April 2023, we conducted a survey of US-based board-certified dermatologists to investigate the impact of the NYT article on prescribing practices of LDOM for alopecia. The survey was conducted as a poll in a Facebook group for board-certified dermatologists and asked, “How did the NYT article on oral minoxidil for alopecia change your utilization of LDOM (low-dose oral minoxidil) for alopecia?” Three answer choices were given: (1) I started Rx’ing LDOM or increased the number of patients I manage with LDOM; (2) No change. I never Rx’d LDOM and/or no increase in utilization; and (3) I was already prescribing LDOM.

Of the 65 total respondents, 27 (42%) reported that the NYT article influenced their decision to start prescribing LDOM for alopecia. Nine respondents (14%) reported that the article did not influence their prescribing habits, and 27 (42%) responded that they were already prescribing the medication prior to the article’s publication.

Data from Epiphany Dermatology, a practice with more than 70 locations throughout the United States, showed that oral minoxidil was prescribed for alopecia 107 times in 2020 and 672 times in 2021 (Amy Hadley, Epiphany Dermatology, written communication, March 24, 2023). In 2022, prescriptions increased exponentially to 1626, and in the period of January 2023 to March 2023 alone, oral minoxidil was prescribed 510 times. Following publication of the NYT article in August 2022, LDOM was prescribed a total of 1377 times in the next 8 months.

Moreover, data from Summit Pharmacy, a retail pharmacy in Centennial, Colorado, showed an 1800% increase in LDOM prescriptions in the 7 months following the NYT article’s publication (August 2022 to March 2023) compared with the 7 months prior (January 2022 to August 2022)(Brandon Johnson, Summit Pharmacy, written communication, March 30, 2023). These data provide evidence for the influence of the NYT article on prescribing habits of dermatology providers in the United States.

The safety of oral minoxidil for use in hair loss has been established through several studies in the literature.4,5 These results show that LDOM may be a safe, readily accessible, and revolutionary treatment for hair loss. A retrospective multicenter study of 1404 patients treated with LDOM for any type of alopecia found that side effects were infrequent, and only 1.7% of patients discontinued treatment due to adverse effects. The most frequent adverse effect was hypertrichosis, occurring in 15.1% of patients but leading to treatment withdrawal in only 0.5% of patients.4 Similarly, Randolph and Tosti5 found that hypertrichosis of the face and body was the most common adverse effect observed, though it rarely resulted in discontinuation and likely was dose dependent: less than 10% of patients receiving 0.25 mg/d experienced hypertrichosis compared with more than 50% of those receiving 5 mg/d (N=634). They also described patients in whom topical minoxidil, though effective, posed major barriers to compliance due to the twice-daily application, changes to hair texture from the medication, and scalp irritation. A literature review of 17 studies with 634 patients on LDOM as a primary treatment for hair loss found that it was an effective, well-tolerated treatment and should be considered for healthy patients who have difficulty with topical formulations.5

In the age of media with data constantly at users’ fingertips, the art of practicing medicine also has changed. Although physicians pride themselves on evidence-based medicine, it appears that an NYT article had an impact on how physicians, particularly dermatologists, prescribe oral minoxidil. However, it is difficult to know if the article exposed dermatologists to another treatment in their armamentarium for hair loss or if it influenced patients to ask their health care provider about LDOM for hair loss. One thing is clear—since the article’s publication, the off-label use of LDOM for alopecia has produced what many may call “miracles” for patients with hair loss.5

- Messenger AG, Rundegren J. Minoxidil: mechanisms of action on hair growth. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:186-194. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05785.x

- Kolata G. An old medicine grows new hair for pennies a day, doctors say. The New York Times. August 18, 2022. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/18/health/minoxidil-hair-loss-pills.html

- The New York Times Company reports third-quarter 2022 results. Press release. The New York Times Company; November 2, 2022. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://nytco-assets.nytimes.com/2022/11/NYT-Press-Release-Q3-2022-Final-nM7GzWGr.pdf

- Vañó-Galván S, Pirmez R, Hermosa-Gelbard A, et al. Safety of low-dose oral minoxidil for hair loss: a multicenter study of 1404 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1644-1651. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.054

- Randolph M, Tosti A. Oral minoxidil treatment for hair loss: a review of efficacy and safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:737-746. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1009

Minoxidil, a potent vasodilator, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1963 to treat high blood pressure. Its application as a hair loss treatment was discovered by accident—patients taking oral minoxidil for blood pressure noticed hair growth on their bodies as a side effect of the medication. In 1988, topical minoxidil (Rogaine [Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc]) was approved by the FDA for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men, and then it was approved for the same indication in women in 1991. The mechanism of action by which minoxidil increases hair growth still has not been fully elucidated. When applied topically, it is thought to extend the anagen phase (or growth phase) of the hair cycle and increase hair follicle size. It also increases oxygen to the hair follicle through vasodilation and stimulates the production of vascular endothelial growth factor, which is thought to promote hair growth.1 Since its approval, topical minoxidil has become a first-line treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men and women.

In August 2022, The New York Times (NYT) published an article on dermatologists’ use of oral minoxidil at a fraction of the dose prescribed for blood pressure with profound results in hair regrowth.2 Several dermatologists quoted in the article endorsed that the decreased dose minimizes unwanted side effects such as hypertrichosis, hypotension, and other cardiac issues while still being effective for hair loss. Also, compared to topical minoxidil, low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) is relatively cheaper and easier to use; topicals are more cumbersome to apply and often leave the hair and scalp sticky, leading to noncompliance among patients.2 Currently, oral minoxidil is not approved by the FDA for use in hair loss, making it an off-label use.

Since the NYT article was published, we have observed an increase in patient questions and requests for LDOM as well as heightened use by fellow dermatologists in our community. As of November 2022, the NYT had approximately 9,330,000 total subscribers, solidifying its place as a newspaper of record in the United States and across the world.3 In April 2023, we conducted a survey of US-based board-certified dermatologists to investigate the impact of the NYT article on prescribing practices of LDOM for alopecia. The survey was conducted as a poll in a Facebook group for board-certified dermatologists and asked, “How did the NYT article on oral minoxidil for alopecia change your utilization of LDOM (low-dose oral minoxidil) for alopecia?” Three answer choices were given: (1) I started Rx’ing LDOM or increased the number of patients I manage with LDOM; (2) No change. I never Rx’d LDOM and/or no increase in utilization; and (3) I was already prescribing LDOM.

Of the 65 total respondents, 27 (42%) reported that the NYT article influenced their decision to start prescribing LDOM for alopecia. Nine respondents (14%) reported that the article did not influence their prescribing habits, and 27 (42%) responded that they were already prescribing the medication prior to the article’s publication.

Data from Epiphany Dermatology, a practice with more than 70 locations throughout the United States, showed that oral minoxidil was prescribed for alopecia 107 times in 2020 and 672 times in 2021 (Amy Hadley, Epiphany Dermatology, written communication, March 24, 2023). In 2022, prescriptions increased exponentially to 1626, and in the period of January 2023 to March 2023 alone, oral minoxidil was prescribed 510 times. Following publication of the NYT article in August 2022, LDOM was prescribed a total of 1377 times in the next 8 months.

Moreover, data from Summit Pharmacy, a retail pharmacy in Centennial, Colorado, showed an 1800% increase in LDOM prescriptions in the 7 months following the NYT article’s publication (August 2022 to March 2023) compared with the 7 months prior (January 2022 to August 2022)(Brandon Johnson, Summit Pharmacy, written communication, March 30, 2023). These data provide evidence for the influence of the NYT article on prescribing habits of dermatology providers in the United States.

The safety of oral minoxidil for use in hair loss has been established through several studies in the literature.4,5 These results show that LDOM may be a safe, readily accessible, and revolutionary treatment for hair loss. A retrospective multicenter study of 1404 patients treated with LDOM for any type of alopecia found that side effects were infrequent, and only 1.7% of patients discontinued treatment due to adverse effects. The most frequent adverse effect was hypertrichosis, occurring in 15.1% of patients but leading to treatment withdrawal in only 0.5% of patients.4 Similarly, Randolph and Tosti5 found that hypertrichosis of the face and body was the most common adverse effect observed, though it rarely resulted in discontinuation and likely was dose dependent: less than 10% of patients receiving 0.25 mg/d experienced hypertrichosis compared with more than 50% of those receiving 5 mg/d (N=634). They also described patients in whom topical minoxidil, though effective, posed major barriers to compliance due to the twice-daily application, changes to hair texture from the medication, and scalp irritation. A literature review of 17 studies with 634 patients on LDOM as a primary treatment for hair loss found that it was an effective, well-tolerated treatment and should be considered for healthy patients who have difficulty with topical formulations.5

In the age of media with data constantly at users’ fingertips, the art of practicing medicine also has changed. Although physicians pride themselves on evidence-based medicine, it appears that an NYT article had an impact on how physicians, particularly dermatologists, prescribe oral minoxidil. However, it is difficult to know if the article exposed dermatologists to another treatment in their armamentarium for hair loss or if it influenced patients to ask their health care provider about LDOM for hair loss. One thing is clear—since the article’s publication, the off-label use of LDOM for alopecia has produced what many may call “miracles” for patients with hair loss.5

Minoxidil, a potent vasodilator, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1963 to treat high blood pressure. Its application as a hair loss treatment was discovered by accident—patients taking oral minoxidil for blood pressure noticed hair growth on their bodies as a side effect of the medication. In 1988, topical minoxidil (Rogaine [Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc]) was approved by the FDA for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men, and then it was approved for the same indication in women in 1991. The mechanism of action by which minoxidil increases hair growth still has not been fully elucidated. When applied topically, it is thought to extend the anagen phase (or growth phase) of the hair cycle and increase hair follicle size. It also increases oxygen to the hair follicle through vasodilation and stimulates the production of vascular endothelial growth factor, which is thought to promote hair growth.1 Since its approval, topical minoxidil has become a first-line treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men and women.

In August 2022, The New York Times (NYT) published an article on dermatologists’ use of oral minoxidil at a fraction of the dose prescribed for blood pressure with profound results in hair regrowth.2 Several dermatologists quoted in the article endorsed that the decreased dose minimizes unwanted side effects such as hypertrichosis, hypotension, and other cardiac issues while still being effective for hair loss. Also, compared to topical minoxidil, low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) is relatively cheaper and easier to use; topicals are more cumbersome to apply and often leave the hair and scalp sticky, leading to noncompliance among patients.2 Currently, oral minoxidil is not approved by the FDA for use in hair loss, making it an off-label use.

Since the NYT article was published, we have observed an increase in patient questions and requests for LDOM as well as heightened use by fellow dermatologists in our community. As of November 2022, the NYT had approximately 9,330,000 total subscribers, solidifying its place as a newspaper of record in the United States and across the world.3 In April 2023, we conducted a survey of US-based board-certified dermatologists to investigate the impact of the NYT article on prescribing practices of LDOM for alopecia. The survey was conducted as a poll in a Facebook group for board-certified dermatologists and asked, “How did the NYT article on oral minoxidil for alopecia change your utilization of LDOM (low-dose oral minoxidil) for alopecia?” Three answer choices were given: (1) I started Rx’ing LDOM or increased the number of patients I manage with LDOM; (2) No change. I never Rx’d LDOM and/or no increase in utilization; and (3) I was already prescribing LDOM.

Of the 65 total respondents, 27 (42%) reported that the NYT article influenced their decision to start prescribing LDOM for alopecia. Nine respondents (14%) reported that the article did not influence their prescribing habits, and 27 (42%) responded that they were already prescribing the medication prior to the article’s publication.

Data from Epiphany Dermatology, a practice with more than 70 locations throughout the United States, showed that oral minoxidil was prescribed for alopecia 107 times in 2020 and 672 times in 2021 (Amy Hadley, Epiphany Dermatology, written communication, March 24, 2023). In 2022, prescriptions increased exponentially to 1626, and in the period of January 2023 to March 2023 alone, oral minoxidil was prescribed 510 times. Following publication of the NYT article in August 2022, LDOM was prescribed a total of 1377 times in the next 8 months.

Moreover, data from Summit Pharmacy, a retail pharmacy in Centennial, Colorado, showed an 1800% increase in LDOM prescriptions in the 7 months following the NYT article’s publication (August 2022 to March 2023) compared with the 7 months prior (January 2022 to August 2022)(Brandon Johnson, Summit Pharmacy, written communication, March 30, 2023). These data provide evidence for the influence of the NYT article on prescribing habits of dermatology providers in the United States.

The safety of oral minoxidil for use in hair loss has been established through several studies in the literature.4,5 These results show that LDOM may be a safe, readily accessible, and revolutionary treatment for hair loss. A retrospective multicenter study of 1404 patients treated with LDOM for any type of alopecia found that side effects were infrequent, and only 1.7% of patients discontinued treatment due to adverse effects. The most frequent adverse effect was hypertrichosis, occurring in 15.1% of patients but leading to treatment withdrawal in only 0.5% of patients.4 Similarly, Randolph and Tosti5 found that hypertrichosis of the face and body was the most common adverse effect observed, though it rarely resulted in discontinuation and likely was dose dependent: less than 10% of patients receiving 0.25 mg/d experienced hypertrichosis compared with more than 50% of those receiving 5 mg/d (N=634). They also described patients in whom topical minoxidil, though effective, posed major barriers to compliance due to the twice-daily application, changes to hair texture from the medication, and scalp irritation. A literature review of 17 studies with 634 patients on LDOM as a primary treatment for hair loss found that it was an effective, well-tolerated treatment and should be considered for healthy patients who have difficulty with topical formulations.5

In the age of media with data constantly at users’ fingertips, the art of practicing medicine also has changed. Although physicians pride themselves on evidence-based medicine, it appears that an NYT article had an impact on how physicians, particularly dermatologists, prescribe oral minoxidil. However, it is difficult to know if the article exposed dermatologists to another treatment in their armamentarium for hair loss or if it influenced patients to ask their health care provider about LDOM for hair loss. One thing is clear—since the article’s publication, the off-label use of LDOM for alopecia has produced what many may call “miracles” for patients with hair loss.5

- Messenger AG, Rundegren J. Minoxidil: mechanisms of action on hair growth. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:186-194. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05785.x

- Kolata G. An old medicine grows new hair for pennies a day, doctors say. The New York Times. August 18, 2022. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/18/health/minoxidil-hair-loss-pills.html

- The New York Times Company reports third-quarter 2022 results. Press release. The New York Times Company; November 2, 2022. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://nytco-assets.nytimes.com/2022/11/NYT-Press-Release-Q3-2022-Final-nM7GzWGr.pdf

- Vañó-Galván S, Pirmez R, Hermosa-Gelbard A, et al. Safety of low-dose oral minoxidil for hair loss: a multicenter study of 1404 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1644-1651. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.054

- Randolph M, Tosti A. Oral minoxidil treatment for hair loss: a review of efficacy and safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:737-746. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1009

- Messenger AG, Rundegren J. Minoxidil: mechanisms of action on hair growth. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:186-194. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05785.x

- Kolata G. An old medicine grows new hair for pennies a day, doctors say. The New York Times. August 18, 2022. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/18/health/minoxidil-hair-loss-pills.html

- The New York Times Company reports third-quarter 2022 results. Press release. The New York Times Company; November 2, 2022. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://nytco-assets.nytimes.com/2022/11/NYT-Press-Release-Q3-2022-Final-nM7GzWGr.pdf

- Vañó-Galván S, Pirmez R, Hermosa-Gelbard A, et al. Safety of low-dose oral minoxidil for hair loss: a multicenter study of 1404 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1644-1651. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.054

- Randolph M, Tosti A. Oral minoxidil treatment for hair loss: a review of efficacy and safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:737-746. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1009

Practice Points

- Low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) prescriptions have increased due to rising attention to its efficacy and safety.

- Media outlets can have a powerful effect on prescribing habits of physicians.

- Physicians should be aware of media trends to help direct patient education.

Erythematous Plaque on the Back of a Newborn

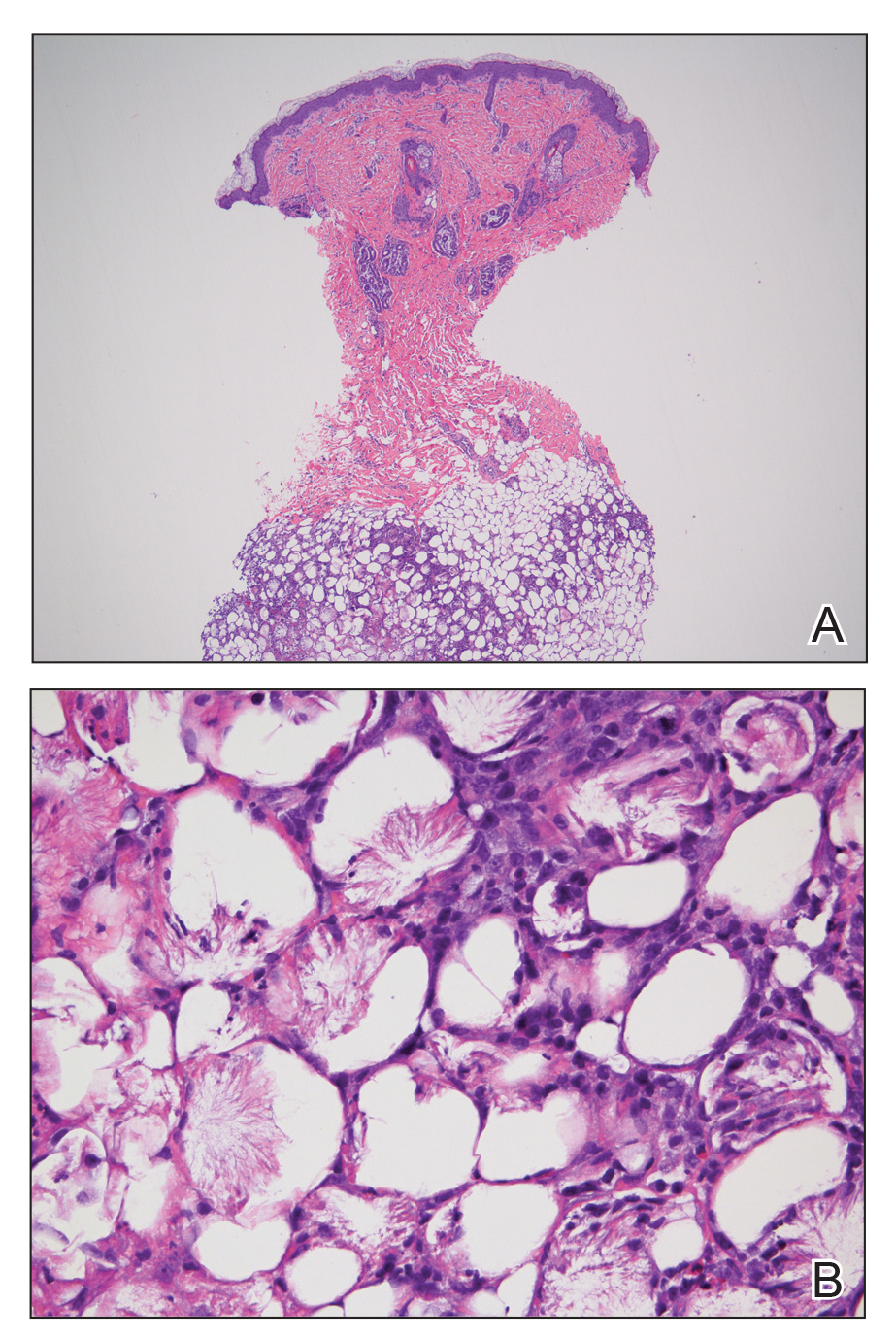

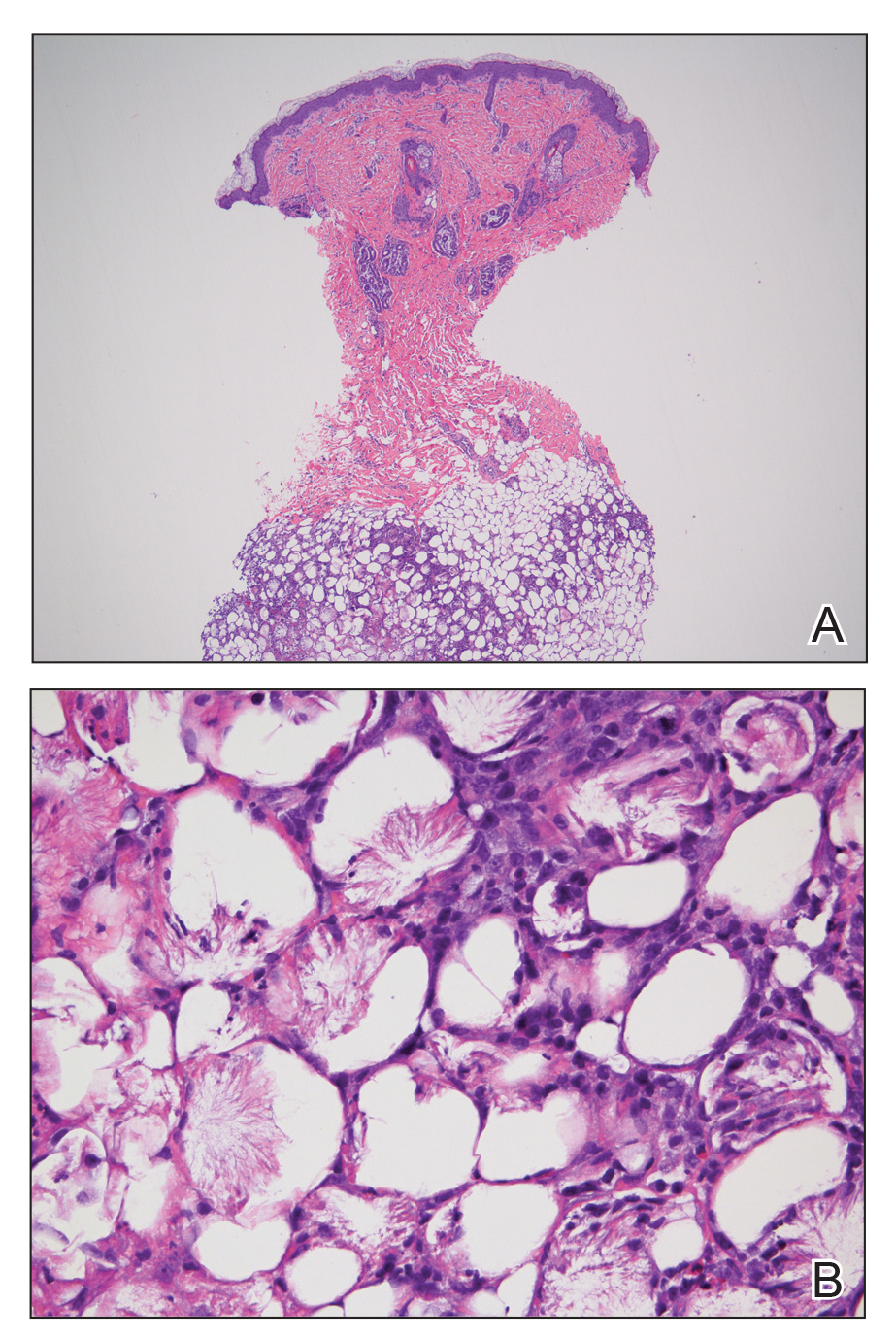

Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn is a benign and self-limited condition that commonly occurs in term to postterm infants.1 However, it is an important diagnosis to recognize, as the potential exists for co-occurring metabolic derangements, most commonly hypercalcemia.1-4 Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn is characterized by a panniculitis, most often on the back, shoulders, face, and buttocks. Lesions commonly present as erythematous nodules and plaques with overlying induration and can appear from birth to up to the first 6 weeks of life; calcification can be present in long-standing cases.2 Biopsy is diagnostic, showing a normal epidermis and dermis with a diffuse lobular panniculitis (Figure, A). Fat degeneration, radial crystal formation, and interstitial histiocytes also can be seen (Figure, B).

Patients with suspected subcutaneous fat necrosis should have their calcium levels checked, as up to 25% of patients may have coexisting hypercalcemia, which can contribute to morbidity and mortality.2 The hypercalcemia can occur with the onset of the lesions; however, it may be seen after they resolve completely.3 Thus, it is recommended that calcium levels be monitored for at least 1 month after lesions resolve. The exact etiology of subcutaneous fat necrosis is unknown, but it has been associated with perinatal stress and neonatal and maternal risk factors such as umbilical cord prolapse, meconium aspiration, neonatal sepsis, preeclampsia, and Rh incompatibility.1 The prognosis generally is excellent, with no treatment necessary for the skin lesions, as they resolve within a few months without subsequent sequelae or scarring.1,2 Patients with hypercalcemia should be treated appropriately with measures such as hydration and restriction of vitamin D; severe cases can be treated with bisphosphonates or loop diuretics.4

Cutis marmorata presents symmetrically on the trunk and may affect the upper and lower extremities as a reticulated erythema, often in response to cold temperature. Lesions are transient and resolve with warming. The isolated location of the skin lesions on the back, consistent course, and induration is unlikely to be seen in cutis marmorata. Infantile hemangiomas present several weeks to months after birth, and they undergo a rapid growth phase and subsequent slower involution phase. Furthermore, infantile hemangiomas have a rubbery feel and typically are not hard plaques, as seen in our patient.5 Patients with bacterial cellulitis often have systemic symptoms such as fever or chills, and the lesion generally is an ill-defined area of erythema and edema that can enlarge and become fluctuant.6 Sclerema neonatorum is a rare condition characterized by diffuse thickening of the skin that occurs in premature infants.7 These patients often are severely ill, as opposed to our asymptomatic full-term patient.

- Rubin G, Spagnut G, Morandi F, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn. Clin Case Rep. 2015;3:1017-1020.

- de Campos Luciano Gomes MP, Porro AM, Simões da Silva Enokihara MM, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn: clinical manifestations in two cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):154-157.

- Karochristou K, Siahanidou T, Kakourou-Tsivitanidou T, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with severe hypocalcemia in a neonate. J Perinatol. 2005;26:64-66.

- Salas IV, Miralbell AR, Peinado CM, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn and hypercalcemia: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:AB149.

- Darrow DH, Greene AK, Mancini AJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of infantile hemangioma. Pediatrics. 2015;136:E1060-E1104.

- Linder KA, Malani PN. Cellulitis. JAMA. 2017;317:2142.

- Jardine D, Atherton DJ, Trompeter RS. Sclerema neonaturm and subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn in the same infant. Eur J Pediatr. 1990;150:125-126.

Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn is a benign and self-limited condition that commonly occurs in term to postterm infants.1 However, it is an important diagnosis to recognize, as the potential exists for co-occurring metabolic derangements, most commonly hypercalcemia.1-4 Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn is characterized by a panniculitis, most often on the back, shoulders, face, and buttocks. Lesions commonly present as erythematous nodules and plaques with overlying induration and can appear from birth to up to the first 6 weeks of life; calcification can be present in long-standing cases.2 Biopsy is diagnostic, showing a normal epidermis and dermis with a diffuse lobular panniculitis (Figure, A). Fat degeneration, radial crystal formation, and interstitial histiocytes also can be seen (Figure, B).

Patients with suspected subcutaneous fat necrosis should have their calcium levels checked, as up to 25% of patients may have coexisting hypercalcemia, which can contribute to morbidity and mortality.2 The hypercalcemia can occur with the onset of the lesions; however, it may be seen after they resolve completely.3 Thus, it is recommended that calcium levels be monitored for at least 1 month after lesions resolve. The exact etiology of subcutaneous fat necrosis is unknown, but it has been associated with perinatal stress and neonatal and maternal risk factors such as umbilical cord prolapse, meconium aspiration, neonatal sepsis, preeclampsia, and Rh incompatibility.1 The prognosis generally is excellent, with no treatment necessary for the skin lesions, as they resolve within a few months without subsequent sequelae or scarring.1,2 Patients with hypercalcemia should be treated appropriately with measures such as hydration and restriction of vitamin D; severe cases can be treated with bisphosphonates or loop diuretics.4

Cutis marmorata presents symmetrically on the trunk and may affect the upper and lower extremities as a reticulated erythema, often in response to cold temperature. Lesions are transient and resolve with warming. The isolated location of the skin lesions on the back, consistent course, and induration is unlikely to be seen in cutis marmorata. Infantile hemangiomas present several weeks to months after birth, and they undergo a rapid growth phase and subsequent slower involution phase. Furthermore, infantile hemangiomas have a rubbery feel and typically are not hard plaques, as seen in our patient.5 Patients with bacterial cellulitis often have systemic symptoms such as fever or chills, and the lesion generally is an ill-defined area of erythema and edema that can enlarge and become fluctuant.6 Sclerema neonatorum is a rare condition characterized by diffuse thickening of the skin that occurs in premature infants.7 These patients often are severely ill, as opposed to our asymptomatic full-term patient.

Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn is a benign and self-limited condition that commonly occurs in term to postterm infants.1 However, it is an important diagnosis to recognize, as the potential exists for co-occurring metabolic derangements, most commonly hypercalcemia.1-4 Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn is characterized by a panniculitis, most often on the back, shoulders, face, and buttocks. Lesions commonly present as erythematous nodules and plaques with overlying induration and can appear from birth to up to the first 6 weeks of life; calcification can be present in long-standing cases.2 Biopsy is diagnostic, showing a normal epidermis and dermis with a diffuse lobular panniculitis (Figure, A). Fat degeneration, radial crystal formation, and interstitial histiocytes also can be seen (Figure, B).

Patients with suspected subcutaneous fat necrosis should have their calcium levels checked, as up to 25% of patients may have coexisting hypercalcemia, which can contribute to morbidity and mortality.2 The hypercalcemia can occur with the onset of the lesions; however, it may be seen after they resolve completely.3 Thus, it is recommended that calcium levels be monitored for at least 1 month after lesions resolve. The exact etiology of subcutaneous fat necrosis is unknown, but it has been associated with perinatal stress and neonatal and maternal risk factors such as umbilical cord prolapse, meconium aspiration, neonatal sepsis, preeclampsia, and Rh incompatibility.1 The prognosis generally is excellent, with no treatment necessary for the skin lesions, as they resolve within a few months without subsequent sequelae or scarring.1,2 Patients with hypercalcemia should be treated appropriately with measures such as hydration and restriction of vitamin D; severe cases can be treated with bisphosphonates or loop diuretics.4

Cutis marmorata presents symmetrically on the trunk and may affect the upper and lower extremities as a reticulated erythema, often in response to cold temperature. Lesions are transient and resolve with warming. The isolated location of the skin lesions on the back, consistent course, and induration is unlikely to be seen in cutis marmorata. Infantile hemangiomas present several weeks to months after birth, and they undergo a rapid growth phase and subsequent slower involution phase. Furthermore, infantile hemangiomas have a rubbery feel and typically are not hard plaques, as seen in our patient.5 Patients with bacterial cellulitis often have systemic symptoms such as fever or chills, and the lesion generally is an ill-defined area of erythema and edema that can enlarge and become fluctuant.6 Sclerema neonatorum is a rare condition characterized by diffuse thickening of the skin that occurs in premature infants.7 These patients often are severely ill, as opposed to our asymptomatic full-term patient.

- Rubin G, Spagnut G, Morandi F, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn. Clin Case Rep. 2015;3:1017-1020.

- de Campos Luciano Gomes MP, Porro AM, Simões da Silva Enokihara MM, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn: clinical manifestations in two cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):154-157.

- Karochristou K, Siahanidou T, Kakourou-Tsivitanidou T, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with severe hypocalcemia in a neonate. J Perinatol. 2005;26:64-66.

- Salas IV, Miralbell AR, Peinado CM, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn and hypercalcemia: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:AB149.

- Darrow DH, Greene AK, Mancini AJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of infantile hemangioma. Pediatrics. 2015;136:E1060-E1104.

- Linder KA, Malani PN. Cellulitis. JAMA. 2017;317:2142.

- Jardine D, Atherton DJ, Trompeter RS. Sclerema neonaturm and subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn in the same infant. Eur J Pediatr. 1990;150:125-126.

- Rubin G, Spagnut G, Morandi F, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn. Clin Case Rep. 2015;3:1017-1020.

- de Campos Luciano Gomes MP, Porro AM, Simões da Silva Enokihara MM, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn: clinical manifestations in two cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):154-157.

- Karochristou K, Siahanidou T, Kakourou-Tsivitanidou T, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with severe hypocalcemia in a neonate. J Perinatol. 2005;26:64-66.

- Salas IV, Miralbell AR, Peinado CM, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn and hypercalcemia: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:AB149.

- Darrow DH, Greene AK, Mancini AJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of infantile hemangioma. Pediatrics. 2015;136:E1060-E1104.

- Linder KA, Malani PN. Cellulitis. JAMA. 2017;317:2142.

- Jardine D, Atherton DJ, Trompeter RS. Sclerema neonaturm and subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn in the same infant. Eur J Pediatr. 1990;150:125-126.

An 8-day-old female infant presented with a mass on the lower back that had been present since birth. The patient was well appearing, alert, and active. Physical examination revealed a 6×5-cm, erythematous, ill-defined, indurated plaque on the lower thoracic back. There was no associated family history of similar findings. According to the mother, the patient was feeding well with no recent fever, irritability, or lethargy. The patient was born via elective induction of labor at term due to maternal intrauterine infection from chorioamnionitis. The birth was complicated by shoulder dystocia with an Erb palsy, and she was hospitalized for 5 days after delivery for management of hypotension and ABO isoimmunization and to rule out sepsis; blood cultures were negative for neonatal infection.