User login

How Media Coverage of Oral Minoxidil for Hair Loss Has Impacted Prescribing Habits

Minoxidil, a potent vasodilator, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1963 to treat high blood pressure. Its application as a hair loss treatment was discovered by accident—patients taking oral minoxidil for blood pressure noticed hair growth on their bodies as a side effect of the medication. In 1988, topical minoxidil (Rogaine [Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc]) was approved by the FDA for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men, and then it was approved for the same indication in women in 1991. The mechanism of action by which minoxidil increases hair growth still has not been fully elucidated. When applied topically, it is thought to extend the anagen phase (or growth phase) of the hair cycle and increase hair follicle size. It also increases oxygen to the hair follicle through vasodilation and stimulates the production of vascular endothelial growth factor, which is thought to promote hair growth.1 Since its approval, topical minoxidil has become a first-line treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men and women.

In August 2022, The New York Times (NYT) published an article on dermatologists’ use of oral minoxidil at a fraction of the dose prescribed for blood pressure with profound results in hair regrowth.2 Several dermatologists quoted in the article endorsed that the decreased dose minimizes unwanted side effects such as hypertrichosis, hypotension, and other cardiac issues while still being effective for hair loss. Also, compared to topical minoxidil, low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) is relatively cheaper and easier to use; topicals are more cumbersome to apply and often leave the hair and scalp sticky, leading to noncompliance among patients.2 Currently, oral minoxidil is not approved by the FDA for use in hair loss, making it an off-label use.

Since the NYT article was published, we have observed an increase in patient questions and requests for LDOM as well as heightened use by fellow dermatologists in our community. As of November 2022, the NYT had approximately 9,330,000 total subscribers, solidifying its place as a newspaper of record in the United States and across the world.3 In April 2023, we conducted a survey of US-based board-certified dermatologists to investigate the impact of the NYT article on prescribing practices of LDOM for alopecia. The survey was conducted as a poll in a Facebook group for board-certified dermatologists and asked, “How did the NYT article on oral minoxidil for alopecia change your utilization of LDOM (low-dose oral minoxidil) for alopecia?” Three answer choices were given: (1) I started Rx’ing LDOM or increased the number of patients I manage with LDOM; (2) No change. I never Rx’d LDOM and/or no increase in utilization; and (3) I was already prescribing LDOM.

Of the 65 total respondents, 27 (42%) reported that the NYT article influenced their decision to start prescribing LDOM for alopecia. Nine respondents (14%) reported that the article did not influence their prescribing habits, and 27 (42%) responded that they were already prescribing the medication prior to the article’s publication.

Data from Epiphany Dermatology, a practice with more than 70 locations throughout the United States, showed that oral minoxidil was prescribed for alopecia 107 times in 2020 and 672 times in 2021 (Amy Hadley, Epiphany Dermatology, written communication, March 24, 2023). In 2022, prescriptions increased exponentially to 1626, and in the period of January 2023 to March 2023 alone, oral minoxidil was prescribed 510 times. Following publication of the NYT article in August 2022, LDOM was prescribed a total of 1377 times in the next 8 months.

Moreover, data from Summit Pharmacy, a retail pharmacy in Centennial, Colorado, showed an 1800% increase in LDOM prescriptions in the 7 months following the NYT article’s publication (August 2022 to March 2023) compared with the 7 months prior (January 2022 to August 2022)(Brandon Johnson, Summit Pharmacy, written communication, March 30, 2023). These data provide evidence for the influence of the NYT article on prescribing habits of dermatology providers in the United States.

The safety of oral minoxidil for use in hair loss has been established through several studies in the literature.4,5 These results show that LDOM may be a safe, readily accessible, and revolutionary treatment for hair loss. A retrospective multicenter study of 1404 patients treated with LDOM for any type of alopecia found that side effects were infrequent, and only 1.7% of patients discontinued treatment due to adverse effects. The most frequent adverse effect was hypertrichosis, occurring in 15.1% of patients but leading to treatment withdrawal in only 0.5% of patients.4 Similarly, Randolph and Tosti5 found that hypertrichosis of the face and body was the most common adverse effect observed, though it rarely resulted in discontinuation and likely was dose dependent: less than 10% of patients receiving 0.25 mg/d experienced hypertrichosis compared with more than 50% of those receiving 5 mg/d (N=634). They also described patients in whom topical minoxidil, though effective, posed major barriers to compliance due to the twice-daily application, changes to hair texture from the medication, and scalp irritation. A literature review of 17 studies with 634 patients on LDOM as a primary treatment for hair loss found that it was an effective, well-tolerated treatment and should be considered for healthy patients who have difficulty with topical formulations.5

In the age of media with data constantly at users’ fingertips, the art of practicing medicine also has changed. Although physicians pride themselves on evidence-based medicine, it appears that an NYT article had an impact on how physicians, particularly dermatologists, prescribe oral minoxidil. However, it is difficult to know if the article exposed dermatologists to another treatment in their armamentarium for hair loss or if it influenced patients to ask their health care provider about LDOM for hair loss. One thing is clear—since the article’s publication, the off-label use of LDOM for alopecia has produced what many may call “miracles” for patients with hair loss.5

- Messenger AG, Rundegren J. Minoxidil: mechanisms of action on hair growth. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:186-194. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05785.x

- Kolata G. An old medicine grows new hair for pennies a day, doctors say. The New York Times. August 18, 2022. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/18/health/minoxidil-hair-loss-pills.html

- The New York Times Company reports third-quarter 2022 results. Press release. The New York Times Company; November 2, 2022. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://nytco-assets.nytimes.com/2022/11/NYT-Press-Release-Q3-2022-Final-nM7GzWGr.pdf

- Vañó-Galván S, Pirmez R, Hermosa-Gelbard A, et al. Safety of low-dose oral minoxidil for hair loss: a multicenter study of 1404 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1644-1651. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.054

- Randolph M, Tosti A. Oral minoxidil treatment for hair loss: a review of efficacy and safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:737-746. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1009

Minoxidil, a potent vasodilator, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1963 to treat high blood pressure. Its application as a hair loss treatment was discovered by accident—patients taking oral minoxidil for blood pressure noticed hair growth on their bodies as a side effect of the medication. In 1988, topical minoxidil (Rogaine [Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc]) was approved by the FDA for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men, and then it was approved for the same indication in women in 1991. The mechanism of action by which minoxidil increases hair growth still has not been fully elucidated. When applied topically, it is thought to extend the anagen phase (or growth phase) of the hair cycle and increase hair follicle size. It also increases oxygen to the hair follicle through vasodilation and stimulates the production of vascular endothelial growth factor, which is thought to promote hair growth.1 Since its approval, topical minoxidil has become a first-line treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men and women.

In August 2022, The New York Times (NYT) published an article on dermatologists’ use of oral minoxidil at a fraction of the dose prescribed for blood pressure with profound results in hair regrowth.2 Several dermatologists quoted in the article endorsed that the decreased dose minimizes unwanted side effects such as hypertrichosis, hypotension, and other cardiac issues while still being effective for hair loss. Also, compared to topical minoxidil, low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) is relatively cheaper and easier to use; topicals are more cumbersome to apply and often leave the hair and scalp sticky, leading to noncompliance among patients.2 Currently, oral minoxidil is not approved by the FDA for use in hair loss, making it an off-label use.

Since the NYT article was published, we have observed an increase in patient questions and requests for LDOM as well as heightened use by fellow dermatologists in our community. As of November 2022, the NYT had approximately 9,330,000 total subscribers, solidifying its place as a newspaper of record in the United States and across the world.3 In April 2023, we conducted a survey of US-based board-certified dermatologists to investigate the impact of the NYT article on prescribing practices of LDOM for alopecia. The survey was conducted as a poll in a Facebook group for board-certified dermatologists and asked, “How did the NYT article on oral minoxidil for alopecia change your utilization of LDOM (low-dose oral minoxidil) for alopecia?” Three answer choices were given: (1) I started Rx’ing LDOM or increased the number of patients I manage with LDOM; (2) No change. I never Rx’d LDOM and/or no increase in utilization; and (3) I was already prescribing LDOM.

Of the 65 total respondents, 27 (42%) reported that the NYT article influenced their decision to start prescribing LDOM for alopecia. Nine respondents (14%) reported that the article did not influence their prescribing habits, and 27 (42%) responded that they were already prescribing the medication prior to the article’s publication.

Data from Epiphany Dermatology, a practice with more than 70 locations throughout the United States, showed that oral minoxidil was prescribed for alopecia 107 times in 2020 and 672 times in 2021 (Amy Hadley, Epiphany Dermatology, written communication, March 24, 2023). In 2022, prescriptions increased exponentially to 1626, and in the period of January 2023 to March 2023 alone, oral minoxidil was prescribed 510 times. Following publication of the NYT article in August 2022, LDOM was prescribed a total of 1377 times in the next 8 months.

Moreover, data from Summit Pharmacy, a retail pharmacy in Centennial, Colorado, showed an 1800% increase in LDOM prescriptions in the 7 months following the NYT article’s publication (August 2022 to March 2023) compared with the 7 months prior (January 2022 to August 2022)(Brandon Johnson, Summit Pharmacy, written communication, March 30, 2023). These data provide evidence for the influence of the NYT article on prescribing habits of dermatology providers in the United States.

The safety of oral minoxidil for use in hair loss has been established through several studies in the literature.4,5 These results show that LDOM may be a safe, readily accessible, and revolutionary treatment for hair loss. A retrospective multicenter study of 1404 patients treated with LDOM for any type of alopecia found that side effects were infrequent, and only 1.7% of patients discontinued treatment due to adverse effects. The most frequent adverse effect was hypertrichosis, occurring in 15.1% of patients but leading to treatment withdrawal in only 0.5% of patients.4 Similarly, Randolph and Tosti5 found that hypertrichosis of the face and body was the most common adverse effect observed, though it rarely resulted in discontinuation and likely was dose dependent: less than 10% of patients receiving 0.25 mg/d experienced hypertrichosis compared with more than 50% of those receiving 5 mg/d (N=634). They also described patients in whom topical minoxidil, though effective, posed major barriers to compliance due to the twice-daily application, changes to hair texture from the medication, and scalp irritation. A literature review of 17 studies with 634 patients on LDOM as a primary treatment for hair loss found that it was an effective, well-tolerated treatment and should be considered for healthy patients who have difficulty with topical formulations.5

In the age of media with data constantly at users’ fingertips, the art of practicing medicine also has changed. Although physicians pride themselves on evidence-based medicine, it appears that an NYT article had an impact on how physicians, particularly dermatologists, prescribe oral minoxidil. However, it is difficult to know if the article exposed dermatologists to another treatment in their armamentarium for hair loss or if it influenced patients to ask their health care provider about LDOM for hair loss. One thing is clear—since the article’s publication, the off-label use of LDOM for alopecia has produced what many may call “miracles” for patients with hair loss.5

Minoxidil, a potent vasodilator, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1963 to treat high blood pressure. Its application as a hair loss treatment was discovered by accident—patients taking oral minoxidil for blood pressure noticed hair growth on their bodies as a side effect of the medication. In 1988, topical minoxidil (Rogaine [Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc]) was approved by the FDA for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men, and then it was approved for the same indication in women in 1991. The mechanism of action by which minoxidil increases hair growth still has not been fully elucidated. When applied topically, it is thought to extend the anagen phase (or growth phase) of the hair cycle and increase hair follicle size. It also increases oxygen to the hair follicle through vasodilation and stimulates the production of vascular endothelial growth factor, which is thought to promote hair growth.1 Since its approval, topical minoxidil has become a first-line treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men and women.

In August 2022, The New York Times (NYT) published an article on dermatologists’ use of oral minoxidil at a fraction of the dose prescribed for blood pressure with profound results in hair regrowth.2 Several dermatologists quoted in the article endorsed that the decreased dose minimizes unwanted side effects such as hypertrichosis, hypotension, and other cardiac issues while still being effective for hair loss. Also, compared to topical minoxidil, low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) is relatively cheaper and easier to use; topicals are more cumbersome to apply and often leave the hair and scalp sticky, leading to noncompliance among patients.2 Currently, oral minoxidil is not approved by the FDA for use in hair loss, making it an off-label use.

Since the NYT article was published, we have observed an increase in patient questions and requests for LDOM as well as heightened use by fellow dermatologists in our community. As of November 2022, the NYT had approximately 9,330,000 total subscribers, solidifying its place as a newspaper of record in the United States and across the world.3 In April 2023, we conducted a survey of US-based board-certified dermatologists to investigate the impact of the NYT article on prescribing practices of LDOM for alopecia. The survey was conducted as a poll in a Facebook group for board-certified dermatologists and asked, “How did the NYT article on oral minoxidil for alopecia change your utilization of LDOM (low-dose oral minoxidil) for alopecia?” Three answer choices were given: (1) I started Rx’ing LDOM or increased the number of patients I manage with LDOM; (2) No change. I never Rx’d LDOM and/or no increase in utilization; and (3) I was already prescribing LDOM.

Of the 65 total respondents, 27 (42%) reported that the NYT article influenced their decision to start prescribing LDOM for alopecia. Nine respondents (14%) reported that the article did not influence their prescribing habits, and 27 (42%) responded that they were already prescribing the medication prior to the article’s publication.

Data from Epiphany Dermatology, a practice with more than 70 locations throughout the United States, showed that oral minoxidil was prescribed for alopecia 107 times in 2020 and 672 times in 2021 (Amy Hadley, Epiphany Dermatology, written communication, March 24, 2023). In 2022, prescriptions increased exponentially to 1626, and in the period of January 2023 to March 2023 alone, oral minoxidil was prescribed 510 times. Following publication of the NYT article in August 2022, LDOM was prescribed a total of 1377 times in the next 8 months.

Moreover, data from Summit Pharmacy, a retail pharmacy in Centennial, Colorado, showed an 1800% increase in LDOM prescriptions in the 7 months following the NYT article’s publication (August 2022 to March 2023) compared with the 7 months prior (January 2022 to August 2022)(Brandon Johnson, Summit Pharmacy, written communication, March 30, 2023). These data provide evidence for the influence of the NYT article on prescribing habits of dermatology providers in the United States.

The safety of oral minoxidil for use in hair loss has been established through several studies in the literature.4,5 These results show that LDOM may be a safe, readily accessible, and revolutionary treatment for hair loss. A retrospective multicenter study of 1404 patients treated with LDOM for any type of alopecia found that side effects were infrequent, and only 1.7% of patients discontinued treatment due to adverse effects. The most frequent adverse effect was hypertrichosis, occurring in 15.1% of patients but leading to treatment withdrawal in only 0.5% of patients.4 Similarly, Randolph and Tosti5 found that hypertrichosis of the face and body was the most common adverse effect observed, though it rarely resulted in discontinuation and likely was dose dependent: less than 10% of patients receiving 0.25 mg/d experienced hypertrichosis compared with more than 50% of those receiving 5 mg/d (N=634). They also described patients in whom topical minoxidil, though effective, posed major barriers to compliance due to the twice-daily application, changes to hair texture from the medication, and scalp irritation. A literature review of 17 studies with 634 patients on LDOM as a primary treatment for hair loss found that it was an effective, well-tolerated treatment and should be considered for healthy patients who have difficulty with topical formulations.5

In the age of media with data constantly at users’ fingertips, the art of practicing medicine also has changed. Although physicians pride themselves on evidence-based medicine, it appears that an NYT article had an impact on how physicians, particularly dermatologists, prescribe oral minoxidil. However, it is difficult to know if the article exposed dermatologists to another treatment in their armamentarium for hair loss or if it influenced patients to ask their health care provider about LDOM for hair loss. One thing is clear—since the article’s publication, the off-label use of LDOM for alopecia has produced what many may call “miracles” for patients with hair loss.5

- Messenger AG, Rundegren J. Minoxidil: mechanisms of action on hair growth. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:186-194. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05785.x

- Kolata G. An old medicine grows new hair for pennies a day, doctors say. The New York Times. August 18, 2022. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/18/health/minoxidil-hair-loss-pills.html

- The New York Times Company reports third-quarter 2022 results. Press release. The New York Times Company; November 2, 2022. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://nytco-assets.nytimes.com/2022/11/NYT-Press-Release-Q3-2022-Final-nM7GzWGr.pdf

- Vañó-Galván S, Pirmez R, Hermosa-Gelbard A, et al. Safety of low-dose oral minoxidil for hair loss: a multicenter study of 1404 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1644-1651. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.054

- Randolph M, Tosti A. Oral minoxidil treatment for hair loss: a review of efficacy and safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:737-746. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1009

- Messenger AG, Rundegren J. Minoxidil: mechanisms of action on hair growth. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:186-194. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05785.x

- Kolata G. An old medicine grows new hair for pennies a day, doctors say. The New York Times. August 18, 2022. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/18/health/minoxidil-hair-loss-pills.html

- The New York Times Company reports third-quarter 2022 results. Press release. The New York Times Company; November 2, 2022. Accessed May 20, 2024. https://nytco-assets.nytimes.com/2022/11/NYT-Press-Release-Q3-2022-Final-nM7GzWGr.pdf

- Vañó-Galván S, Pirmez R, Hermosa-Gelbard A, et al. Safety of low-dose oral minoxidil for hair loss: a multicenter study of 1404 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1644-1651. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.054

- Randolph M, Tosti A. Oral minoxidil treatment for hair loss: a review of efficacy and safety. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:737-746. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1009

Practice Points

- Low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) prescriptions have increased due to rising attention to its efficacy and safety.

- Media outlets can have a powerful effect on prescribing habits of physicians.

- Physicians should be aware of media trends to help direct patient education.

Asymptomatic Umbilical Nodule

The Diagnosis: Sister Mary Joseph Nodule

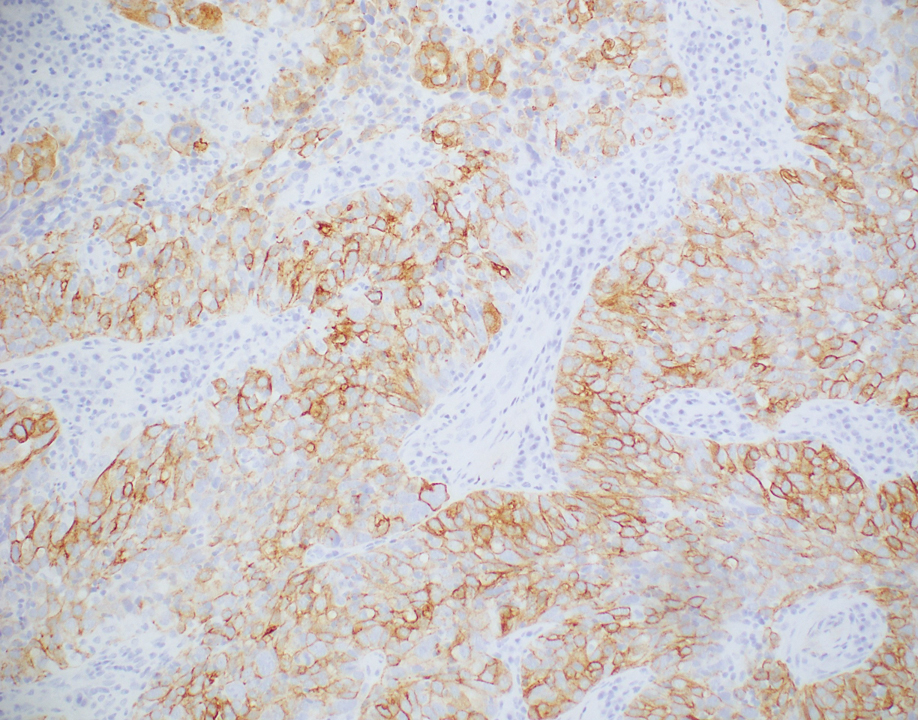

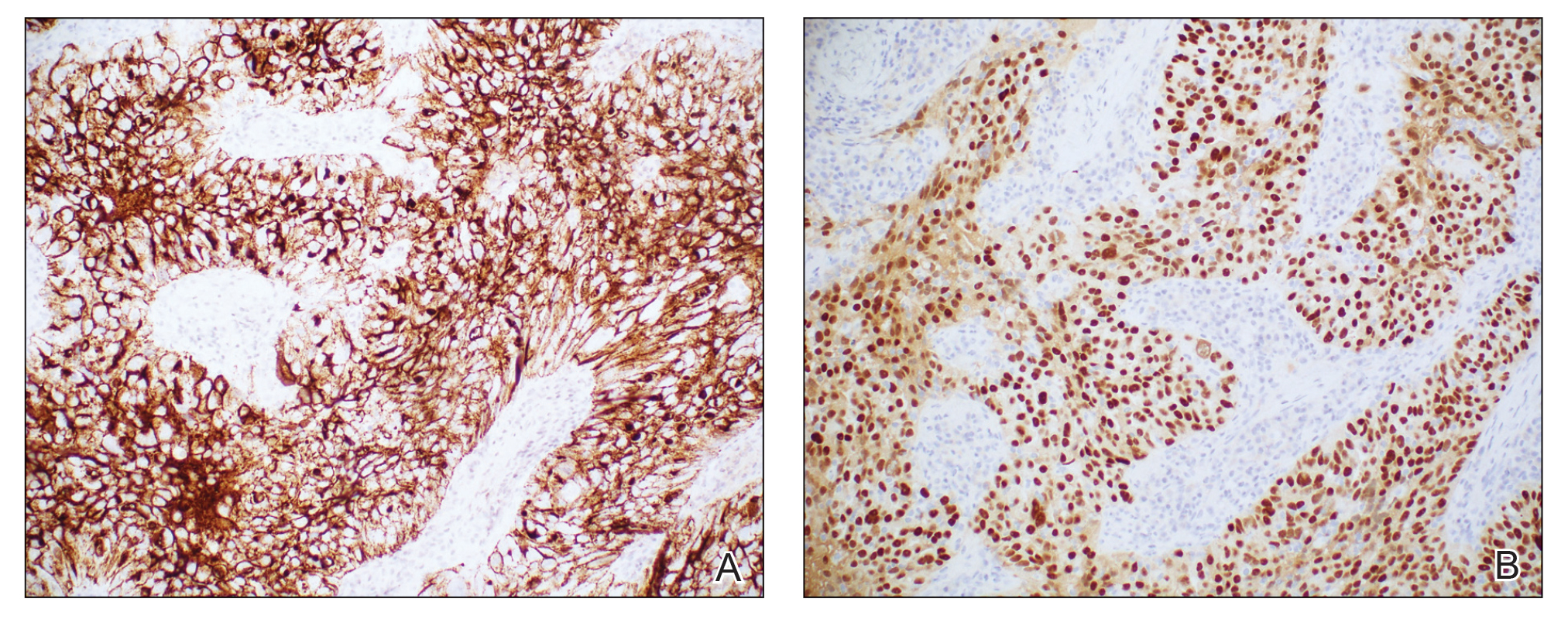

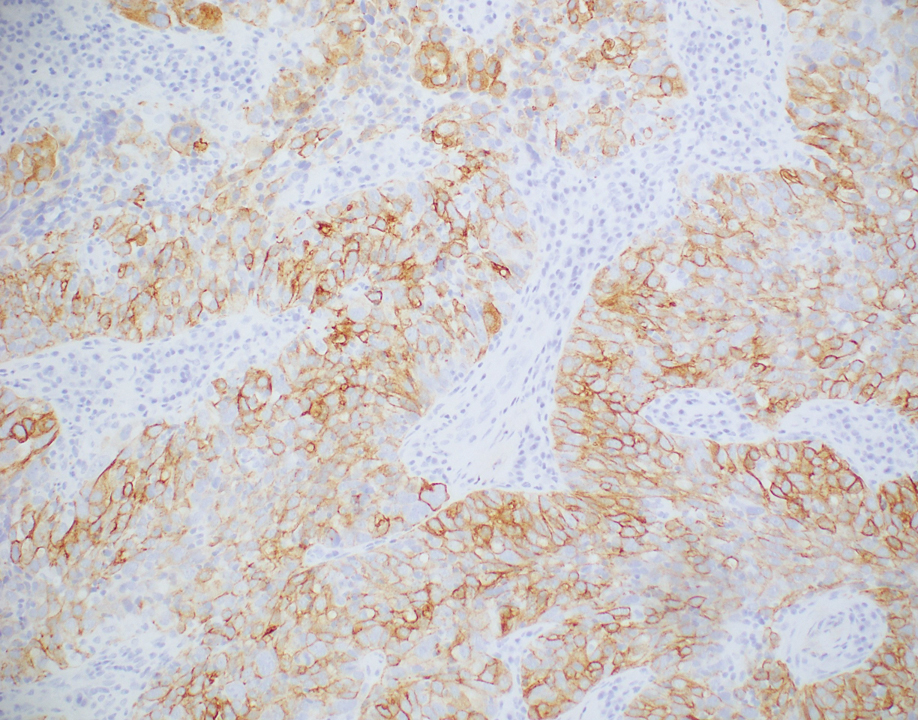

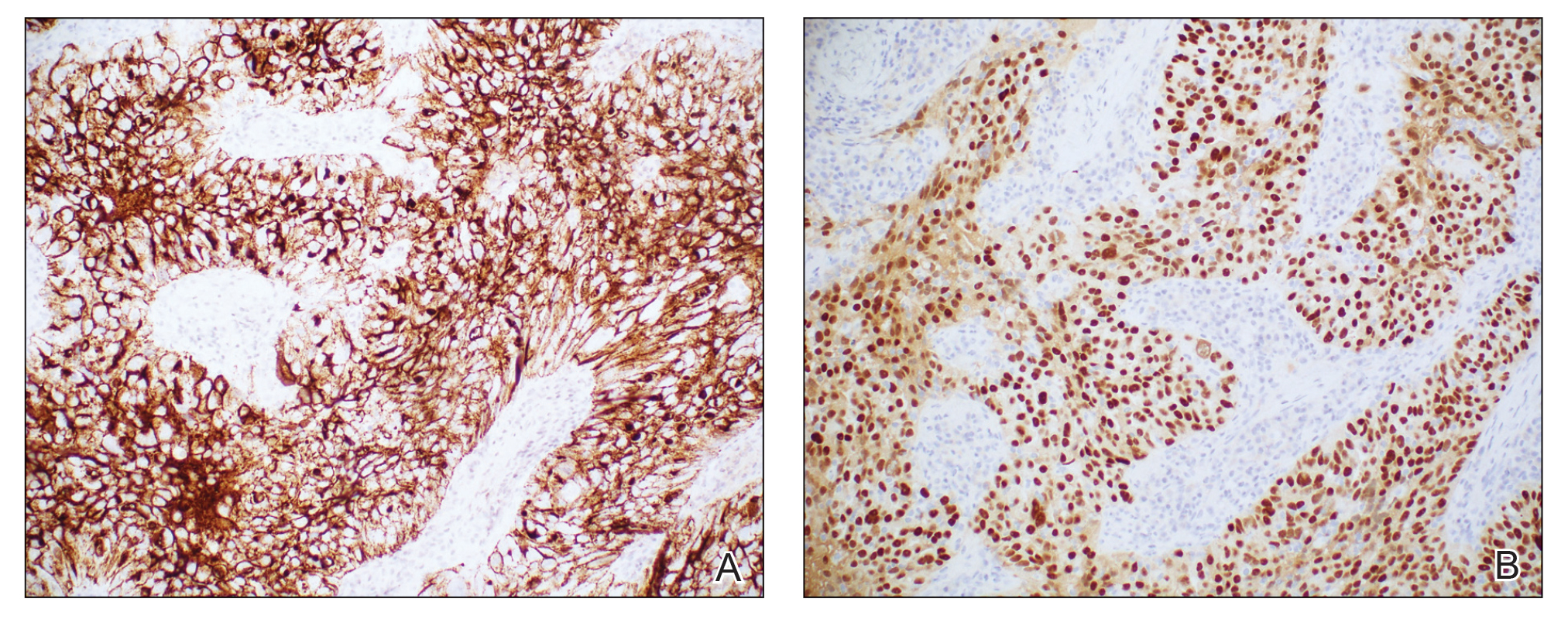

Histopathologic analysis of the biopsy specimen revealed a dense infiltrate of large, hyperchromatic, mucin-producing cells exhibiting varying degrees of nuclear pleomorphism (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was negative for cytokeratin (CK) 20; however, CK7 was found positive (Figure 2), which confirmed the presence of a metastatic adenocarcinoma, consistent with the clinical diagnosis of a Sister Mary Joseph nodule (SMJN). Subsequent IHC workup to determine the site of origin revealed densely positive expression of both cancer antigen 125 and paired homeobox gene 8 (PAX-8)(Figure 3), consistent with primary ovarian disease. Furthermore, expression of estrogen receptor and p53 both were positive within the nuclei, illustrating an aberrant expression pattern. On the other hand, cancer antigen 19-9, caudal-type homeobox 2, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, and mammaglobin were all determined negative, thus leading to the pathologic diagnosis of a metastatic ovarian adenocarcinoma. Additional workup with computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis highlighted a large left ovarian mass with multiple omental nodules as well as enlarged retroperitoneal and pelvic lymph nodes.

The SMJN is a rare presentation of internal malignancy that appears as a nodule that metastasizes to the umbilicus. It may be ulcerated or necrotic and is seen in up to 10% of patients with cutaneous metastases from internal malignancy.1 These nodules are named after Sister Mary Joseph, the surgical assistant of Dr. William Mayo who first described the relationship between umbilical nodules seen in patients with gastrointestinal and genitourinary cancer. The most common underlying malignancies include primary gastrointestinal and gynecologic adenocarcinomas. In a retrospective study of 34 patients by Chalya et al,2 the stomach was found to be the most common primary site (41.1%). The presence of an SMJN affords a poor prognosis, with a mean overall survival of 11 months from the time of diagnosis.3 The mechanism of disease dissemination remains unknown but is thought to occur through lymphovascular invasion of tumor cells and spread via the umbilical ligament.1,4

Merkel cell carcinoma is a cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor that most commonly presents in elderly patients as red-violet nodules or plaques. Although Merkel cell carcinoma most frequently is encountered on sun-exposed skin, they also can arise on the trunk and abdomen. Positive IHC staining for CK20 would be expected; however, it was negative in our case.5

Cutaneous endometriosis is a rare disease presentation and most commonly occurs as a secondary process due to surgical inoculation of the abdominal wall. Primary cutaneous endometriosis in which there is no history of abdominal surgery less frequently is encountered. Patients typically will report pain and cyclical bleeding with menses. Pathology demonstrates ectopic endometrial tissue with glands and uterine myxoid stroma.6

Amelanotic melanoma is an uncommon subtype of malignant melanoma that presents as nonpigmented nodules that have a propensity to ulcerate and bleed. Furthermore, the umbilicus is an exceedingly rare location for primary melanoma. However, one report does exist, and amelanotic melanoma should be considered in the differential for patients with umbilical nodules.7

Dermoid cysts are benign congenital lesions that typically present as a painless, slow-growing, and wellcircumscribed nodule, as similarly experienced by our patient. They most commonly are found on the testicles and ovaries but also are known to arise in embryologic fusion planes, and reports of umbilical lesions exist.8 Dermoid cysts are diagnosed based on histopathology, supporting the need for a biopsy to distinguish a malignant process from benign lesions.9

- Gabriele R, Conte M, Egidi F, et al. Umbilical metastases: current viewpoint. World J Surg Oncol. 2005;3:13.

- Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Rambau PF, et al. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule at a university teaching hospital in northwestern Tanzania: a retrospective review of 34 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:151.

- Leyrat B, Bernadach M, Ginzac A, et al. Sister Mary Joseph nodules: a case report about a rare location of skin metastasis. Case Rep Oncol. 2021;14:664-670.

- Yendluri V, Centeno B, Springett GM. Pancreatic cancer presenting as a Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule: case report and update of the literature. Pancreas. 2007;34:161-164.

- Uchi H. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and immunotherapy. Front Oncol. 2018;8:48.

- Bittar PG, Hryneewycz KT, Bryant EA. Primary cutaneous endometriosis presenting as an umbilical nodule. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1227.

- Kovitwanichkanont T, Joseph S, Yip L. Hidden in plain sight: umbilical melanoma [published online January 28, 2020]. Med J Aust. 2020;212:154-155.e1.

- Prior A, Anania P, Pacetti M, et al. Dermoid and epidermoid cysts of scalp: case series of 234 consecutive patients. World Neurosurg. 2018;120:119-124.

- Akinci O, Turker C, Erturk MS, et al. Umbilical dermoid cyst: a rare case. Cerrahpasa Med J. 2020;44:51-53.

The Diagnosis: Sister Mary Joseph Nodule

Histopathologic analysis of the biopsy specimen revealed a dense infiltrate of large, hyperchromatic, mucin-producing cells exhibiting varying degrees of nuclear pleomorphism (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was negative for cytokeratin (CK) 20; however, CK7 was found positive (Figure 2), which confirmed the presence of a metastatic adenocarcinoma, consistent with the clinical diagnosis of a Sister Mary Joseph nodule (SMJN). Subsequent IHC workup to determine the site of origin revealed densely positive expression of both cancer antigen 125 and paired homeobox gene 8 (PAX-8)(Figure 3), consistent with primary ovarian disease. Furthermore, expression of estrogen receptor and p53 both were positive within the nuclei, illustrating an aberrant expression pattern. On the other hand, cancer antigen 19-9, caudal-type homeobox 2, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, and mammaglobin were all determined negative, thus leading to the pathologic diagnosis of a metastatic ovarian adenocarcinoma. Additional workup with computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis highlighted a large left ovarian mass with multiple omental nodules as well as enlarged retroperitoneal and pelvic lymph nodes.

The SMJN is a rare presentation of internal malignancy that appears as a nodule that metastasizes to the umbilicus. It may be ulcerated or necrotic and is seen in up to 10% of patients with cutaneous metastases from internal malignancy.1 These nodules are named after Sister Mary Joseph, the surgical assistant of Dr. William Mayo who first described the relationship between umbilical nodules seen in patients with gastrointestinal and genitourinary cancer. The most common underlying malignancies include primary gastrointestinal and gynecologic adenocarcinomas. In a retrospective study of 34 patients by Chalya et al,2 the stomach was found to be the most common primary site (41.1%). The presence of an SMJN affords a poor prognosis, with a mean overall survival of 11 months from the time of diagnosis.3 The mechanism of disease dissemination remains unknown but is thought to occur through lymphovascular invasion of tumor cells and spread via the umbilical ligament.1,4

Merkel cell carcinoma is a cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor that most commonly presents in elderly patients as red-violet nodules or plaques. Although Merkel cell carcinoma most frequently is encountered on sun-exposed skin, they also can arise on the trunk and abdomen. Positive IHC staining for CK20 would be expected; however, it was negative in our case.5

Cutaneous endometriosis is a rare disease presentation and most commonly occurs as a secondary process due to surgical inoculation of the abdominal wall. Primary cutaneous endometriosis in which there is no history of abdominal surgery less frequently is encountered. Patients typically will report pain and cyclical bleeding with menses. Pathology demonstrates ectopic endometrial tissue with glands and uterine myxoid stroma.6

Amelanotic melanoma is an uncommon subtype of malignant melanoma that presents as nonpigmented nodules that have a propensity to ulcerate and bleed. Furthermore, the umbilicus is an exceedingly rare location for primary melanoma. However, one report does exist, and amelanotic melanoma should be considered in the differential for patients with umbilical nodules.7

Dermoid cysts are benign congenital lesions that typically present as a painless, slow-growing, and wellcircumscribed nodule, as similarly experienced by our patient. They most commonly are found on the testicles and ovaries but also are known to arise in embryologic fusion planes, and reports of umbilical lesions exist.8 Dermoid cysts are diagnosed based on histopathology, supporting the need for a biopsy to distinguish a malignant process from benign lesions.9

The Diagnosis: Sister Mary Joseph Nodule

Histopathologic analysis of the biopsy specimen revealed a dense infiltrate of large, hyperchromatic, mucin-producing cells exhibiting varying degrees of nuclear pleomorphism (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was negative for cytokeratin (CK) 20; however, CK7 was found positive (Figure 2), which confirmed the presence of a metastatic adenocarcinoma, consistent with the clinical diagnosis of a Sister Mary Joseph nodule (SMJN). Subsequent IHC workup to determine the site of origin revealed densely positive expression of both cancer antigen 125 and paired homeobox gene 8 (PAX-8)(Figure 3), consistent with primary ovarian disease. Furthermore, expression of estrogen receptor and p53 both were positive within the nuclei, illustrating an aberrant expression pattern. On the other hand, cancer antigen 19-9, caudal-type homeobox 2, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, and mammaglobin were all determined negative, thus leading to the pathologic diagnosis of a metastatic ovarian adenocarcinoma. Additional workup with computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis highlighted a large left ovarian mass with multiple omental nodules as well as enlarged retroperitoneal and pelvic lymph nodes.

The SMJN is a rare presentation of internal malignancy that appears as a nodule that metastasizes to the umbilicus. It may be ulcerated or necrotic and is seen in up to 10% of patients with cutaneous metastases from internal malignancy.1 These nodules are named after Sister Mary Joseph, the surgical assistant of Dr. William Mayo who first described the relationship between umbilical nodules seen in patients with gastrointestinal and genitourinary cancer. The most common underlying malignancies include primary gastrointestinal and gynecologic adenocarcinomas. In a retrospective study of 34 patients by Chalya et al,2 the stomach was found to be the most common primary site (41.1%). The presence of an SMJN affords a poor prognosis, with a mean overall survival of 11 months from the time of diagnosis.3 The mechanism of disease dissemination remains unknown but is thought to occur through lymphovascular invasion of tumor cells and spread via the umbilical ligament.1,4

Merkel cell carcinoma is a cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor that most commonly presents in elderly patients as red-violet nodules or plaques. Although Merkel cell carcinoma most frequently is encountered on sun-exposed skin, they also can arise on the trunk and abdomen. Positive IHC staining for CK20 would be expected; however, it was negative in our case.5

Cutaneous endometriosis is a rare disease presentation and most commonly occurs as a secondary process due to surgical inoculation of the abdominal wall. Primary cutaneous endometriosis in which there is no history of abdominal surgery less frequently is encountered. Patients typically will report pain and cyclical bleeding with menses. Pathology demonstrates ectopic endometrial tissue with glands and uterine myxoid stroma.6

Amelanotic melanoma is an uncommon subtype of malignant melanoma that presents as nonpigmented nodules that have a propensity to ulcerate and bleed. Furthermore, the umbilicus is an exceedingly rare location for primary melanoma. However, one report does exist, and amelanotic melanoma should be considered in the differential for patients with umbilical nodules.7

Dermoid cysts are benign congenital lesions that typically present as a painless, slow-growing, and wellcircumscribed nodule, as similarly experienced by our patient. They most commonly are found on the testicles and ovaries but also are known to arise in embryologic fusion planes, and reports of umbilical lesions exist.8 Dermoid cysts are diagnosed based on histopathology, supporting the need for a biopsy to distinguish a malignant process from benign lesions.9

- Gabriele R, Conte M, Egidi F, et al. Umbilical metastases: current viewpoint. World J Surg Oncol. 2005;3:13.

- Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Rambau PF, et al. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule at a university teaching hospital in northwestern Tanzania: a retrospective review of 34 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:151.

- Leyrat B, Bernadach M, Ginzac A, et al. Sister Mary Joseph nodules: a case report about a rare location of skin metastasis. Case Rep Oncol. 2021;14:664-670.

- Yendluri V, Centeno B, Springett GM. Pancreatic cancer presenting as a Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule: case report and update of the literature. Pancreas. 2007;34:161-164.

- Uchi H. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and immunotherapy. Front Oncol. 2018;8:48.

- Bittar PG, Hryneewycz KT, Bryant EA. Primary cutaneous endometriosis presenting as an umbilical nodule. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1227.

- Kovitwanichkanont T, Joseph S, Yip L. Hidden in plain sight: umbilical melanoma [published online January 28, 2020]. Med J Aust. 2020;212:154-155.e1.

- Prior A, Anania P, Pacetti M, et al. Dermoid and epidermoid cysts of scalp: case series of 234 consecutive patients. World Neurosurg. 2018;120:119-124.

- Akinci O, Turker C, Erturk MS, et al. Umbilical dermoid cyst: a rare case. Cerrahpasa Med J. 2020;44:51-53.

- Gabriele R, Conte M, Egidi F, et al. Umbilical metastases: current viewpoint. World J Surg Oncol. 2005;3:13.

- Chalya PL, Mabula JB, Rambau PF, et al. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule at a university teaching hospital in northwestern Tanzania: a retrospective review of 34 cases. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:151.

- Leyrat B, Bernadach M, Ginzac A, et al. Sister Mary Joseph nodules: a case report about a rare location of skin metastasis. Case Rep Oncol. 2021;14:664-670.

- Yendluri V, Centeno B, Springett GM. Pancreatic cancer presenting as a Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule: case report and update of the literature. Pancreas. 2007;34:161-164.

- Uchi H. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and immunotherapy. Front Oncol. 2018;8:48.

- Bittar PG, Hryneewycz KT, Bryant EA. Primary cutaneous endometriosis presenting as an umbilical nodule. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1227.

- Kovitwanichkanont T, Joseph S, Yip L. Hidden in plain sight: umbilical melanoma [published online January 28, 2020]. Med J Aust. 2020;212:154-155.e1.

- Prior A, Anania P, Pacetti M, et al. Dermoid and epidermoid cysts of scalp: case series of 234 consecutive patients. World Neurosurg. 2018;120:119-124.

- Akinci O, Turker C, Erturk MS, et al. Umbilical dermoid cyst: a rare case. Cerrahpasa Med J. 2020;44:51-53.

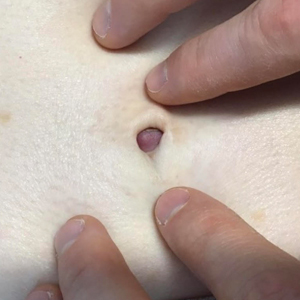

A 64-year-old woman with no notable medical history was referred to our dermatology clinic with an intermittent eczematous rash around the eyelids of 3 months’ duration. While performing a total-body skin examination, a firm pink nodule with a smooth surface incidentally was discovered on the umbilicus. The patient was uncertain when the lesion first appeared and denied any associated symptoms including pain and bleeding. Additionally, a lymph node examination revealed right inguinal lymphadenopathy. Upon further questioning, she reported worsening muscle weakness, fatigue, night sweats, and an unintentional weight loss of 10 pounds. A 6-mm punch biopsy of the umbilical lesion was obtained for routine histopathology.

Hydrogen Peroxide as a Hemostatic Agent During Dermatologic Surgery

The number of skin cancer surgeries continues to rise, especially in the older population, many of whom are on blood thinners. The sequela of bleeding, even in minor cases, is one of the most frequently encountered complications of cutaneous surgery. Surgical site bleeding can increase the risk for infection, skin graft failure, wound dehiscence, and hematoma formation, which may lead to disrupted wound healing and eventual poor scar outcome. Although achieving hemostasis is important, it is recommended to limit certain alternative modalities such as electrosurgery due to the accompanied thermal tissue damage that in turn can prolong healing time, worsen scarring, and increase the risk for infection.1

Practice Gap

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a common topical antiseptic used to clean wounds by killing pathogens through oxidation burst and local oxygen production.2 It is generally affordable, nonallergenic, and easy to obtain. We describe our positive experience using H2O2 as a hemostatic agent during dermatologic surgery, highlighting the agent’s underutilization as well as the recent literature negating traditional viewpoints that it probably causes tissue necrosis and impaired wound healing through its high oxidative property.

The Technique

Before surgery, the site is prepared with chlorhexidine gluconate. A stack of 4×4-in gauze on the surgical tray is saturated with 3% H2O2 and used by the surgeon and surgical assistant throughout the procedure. We currently use this technique during standard excisions, Mohs micrographic surgery stages, repairs, and dermabrasion. Additionally, as a first measure of hemostasis, we recommend H2O2 soaks immediately postoperatively in patients with active bleeding.

We have been utilizing this technique since H2O2 was described as an intraprocedural hemostatic agent during manual dermabrasion.3 Hydrogen peroxide is known to facilitate hemostasis with several accepted mechanisms that include regulating the contractility and barrier function of endothelial cells, activating latent cell surface tissue factor and platelet aggregation, and stimulating platelet-derived growth factor activation.4 It has been reported that increasing H2O2 levels leads to a dose-response increase in aggregation in the presence of subaggregating amounts of collagen.5 This concept was described in an article that utilizes H2O2 as a way to obtain hemostasis before skin grafting burn patients.6 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms h202, hydrogen peroxide, hemostasis, wound healing, surgery, and wound produced several surgical specialties—neurosurgery, orthopedics, gastroenterology, and maxillofacial surgery—that also utilize H2O2 as a hemostatic agent.7,8 One article described a dual-enzyme H2O2 generation machinery in hydrogels as a novel antimicrobial wound treatment.9

Practice Implications

The use of H2O2 as a topical hemostatic agent during surgery was described in 1984.2 The use of H2O2 is not suggested as a substitute for other strong and well-known hemostatic agents, such as aluminum chloride and ferric subsulfate, but rather as a technique that can be used in conjunction with standard methods of hemostasis and antisepsis. For surgical sites that are intended to be closed, we do not suggest these hemostatic agents, as they are known to be caustic, irritating, and pigmenting. In addition to H2O2’s known hemostatic and antiseptic properties, more recent literature invalidates wound impairment concerns and describes its possible role in signaling effector cells to respond downstream, contributing to tissue formation and remodeling.4 The use of H2O2 in wound and incision care has been controversial and avoided due to described skin irritation and possible premature removal of suture10; however, positive biochemical effects of H2O2 on acute wounds have been reported and dispel arguments that this agent causes tissue damage.4 Contrary to the traditional viewpoint that H2O2 probably impairs tissue through its high oxidative property, a proper level of H2O2 is considered an important requirement for normal wound healing. The report published in 1985 that raised concerns of H2O2 causing impaired wound healing through its effect on fibroblasts has been challenged given that the killed cultured fibroblasts were in an in vitro model and not likely representative of the complexities of a healing wound.10 In our experience, the use of H2O2 has not demonstrated any impairments or delays in wound healing, and we postulate that the exposure to H2O2 as described in our technique is not sufficient to cause notable impairment in fibroblast function in vivo. In addition, the role of H2O2 promoting oxidative stress as well as resolving inflammation may suggest it serves as a bidirectional regulator.

Future Directions

Additional studies are needed to assess this precise balance of H2O2 forming a favorable microenvironment in wounds. Similarly, although we discuss minimal and brief use of H2O2 during a procedure, the lack of data on the role of H2O2 as a prophylactic anti-infective agent for postoperative wound care also may be an area of future exploration.

- Henley J, Brewer JD. Newer hemostatic agents used in the practice of dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Res Pract. 2013;2013:279289.

- Hankin FM, Campbell SE, Goldstein SA, et al. Hydrogen peroxide as a topical hemostatic agent. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;186:244-247.

- Weiss J, Winkleman FJ, Titone A, et al. Evaluation of hydrogen peroxide as an intraprocedural hemostatic agent in manual dermabrasion. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1601-1603.

- Zhu G, Wang Q, Lu S, et al. Hydrogen peroxide: a potential wound therapeutic target? Med Princ Pract. 2017;26:301-308.

- Practicò D, Iuliano L, Ghiselli A, et al. Hydrogen peroxide as trigger of platelet aggregation. Haemostasis. 1991;21:169-174.

- Potyondy L, Lottenberg L, Anderson J, et al. The use of hydrogen peroxide for achieving dermal hemostasis after burn excision in a patient with platelet dysfunction. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27:99-101.

- Mawk JR. Hydrogen peroxide for hemostasis. Neurosurgery. 1986;18:827.

- Arakeri G, Brennan PA. Povidone-iodine and hydrogen peroxide mixture soaked gauze pack: a novel hemostatic technique. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71:1833.e1-1833.e3.

- Huber D, Tegl G, Mensah A, et al. A dual-enzyme hydrogen peroxide generation machinery in hydrogels supports antimicrobial wound treatment. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9:15307-15316.

- Lineaweaver W, McMorris S, Soucy D, et al. Cellular and bacterial toxicities of topical antimicrobials. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;75:394-396.

The number of skin cancer surgeries continues to rise, especially in the older population, many of whom are on blood thinners. The sequela of bleeding, even in minor cases, is one of the most frequently encountered complications of cutaneous surgery. Surgical site bleeding can increase the risk for infection, skin graft failure, wound dehiscence, and hematoma formation, which may lead to disrupted wound healing and eventual poor scar outcome. Although achieving hemostasis is important, it is recommended to limit certain alternative modalities such as electrosurgery due to the accompanied thermal tissue damage that in turn can prolong healing time, worsen scarring, and increase the risk for infection.1

Practice Gap

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a common topical antiseptic used to clean wounds by killing pathogens through oxidation burst and local oxygen production.2 It is generally affordable, nonallergenic, and easy to obtain. We describe our positive experience using H2O2 as a hemostatic agent during dermatologic surgery, highlighting the agent’s underutilization as well as the recent literature negating traditional viewpoints that it probably causes tissue necrosis and impaired wound healing through its high oxidative property.

The Technique

Before surgery, the site is prepared with chlorhexidine gluconate. A stack of 4×4-in gauze on the surgical tray is saturated with 3% H2O2 and used by the surgeon and surgical assistant throughout the procedure. We currently use this technique during standard excisions, Mohs micrographic surgery stages, repairs, and dermabrasion. Additionally, as a first measure of hemostasis, we recommend H2O2 soaks immediately postoperatively in patients with active bleeding.

We have been utilizing this technique since H2O2 was described as an intraprocedural hemostatic agent during manual dermabrasion.3 Hydrogen peroxide is known to facilitate hemostasis with several accepted mechanisms that include regulating the contractility and barrier function of endothelial cells, activating latent cell surface tissue factor and platelet aggregation, and stimulating platelet-derived growth factor activation.4 It has been reported that increasing H2O2 levels leads to a dose-response increase in aggregation in the presence of subaggregating amounts of collagen.5 This concept was described in an article that utilizes H2O2 as a way to obtain hemostasis before skin grafting burn patients.6 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms h202, hydrogen peroxide, hemostasis, wound healing, surgery, and wound produced several surgical specialties—neurosurgery, orthopedics, gastroenterology, and maxillofacial surgery—that also utilize H2O2 as a hemostatic agent.7,8 One article described a dual-enzyme H2O2 generation machinery in hydrogels as a novel antimicrobial wound treatment.9

Practice Implications

The use of H2O2 as a topical hemostatic agent during surgery was described in 1984.2 The use of H2O2 is not suggested as a substitute for other strong and well-known hemostatic agents, such as aluminum chloride and ferric subsulfate, but rather as a technique that can be used in conjunction with standard methods of hemostasis and antisepsis. For surgical sites that are intended to be closed, we do not suggest these hemostatic agents, as they are known to be caustic, irritating, and pigmenting. In addition to H2O2’s known hemostatic and antiseptic properties, more recent literature invalidates wound impairment concerns and describes its possible role in signaling effector cells to respond downstream, contributing to tissue formation and remodeling.4 The use of H2O2 in wound and incision care has been controversial and avoided due to described skin irritation and possible premature removal of suture10; however, positive biochemical effects of H2O2 on acute wounds have been reported and dispel arguments that this agent causes tissue damage.4 Contrary to the traditional viewpoint that H2O2 probably impairs tissue through its high oxidative property, a proper level of H2O2 is considered an important requirement for normal wound healing. The report published in 1985 that raised concerns of H2O2 causing impaired wound healing through its effect on fibroblasts has been challenged given that the killed cultured fibroblasts were in an in vitro model and not likely representative of the complexities of a healing wound.10 In our experience, the use of H2O2 has not demonstrated any impairments or delays in wound healing, and we postulate that the exposure to H2O2 as described in our technique is not sufficient to cause notable impairment in fibroblast function in vivo. In addition, the role of H2O2 promoting oxidative stress as well as resolving inflammation may suggest it serves as a bidirectional regulator.

Future Directions

Additional studies are needed to assess this precise balance of H2O2 forming a favorable microenvironment in wounds. Similarly, although we discuss minimal and brief use of H2O2 during a procedure, the lack of data on the role of H2O2 as a prophylactic anti-infective agent for postoperative wound care also may be an area of future exploration.

The number of skin cancer surgeries continues to rise, especially in the older population, many of whom are on blood thinners. The sequela of bleeding, even in minor cases, is one of the most frequently encountered complications of cutaneous surgery. Surgical site bleeding can increase the risk for infection, skin graft failure, wound dehiscence, and hematoma formation, which may lead to disrupted wound healing and eventual poor scar outcome. Although achieving hemostasis is important, it is recommended to limit certain alternative modalities such as electrosurgery due to the accompanied thermal tissue damage that in turn can prolong healing time, worsen scarring, and increase the risk for infection.1

Practice Gap

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a common topical antiseptic used to clean wounds by killing pathogens through oxidation burst and local oxygen production.2 It is generally affordable, nonallergenic, and easy to obtain. We describe our positive experience using H2O2 as a hemostatic agent during dermatologic surgery, highlighting the agent’s underutilization as well as the recent literature negating traditional viewpoints that it probably causes tissue necrosis and impaired wound healing through its high oxidative property.

The Technique

Before surgery, the site is prepared with chlorhexidine gluconate. A stack of 4×4-in gauze on the surgical tray is saturated with 3% H2O2 and used by the surgeon and surgical assistant throughout the procedure. We currently use this technique during standard excisions, Mohs micrographic surgery stages, repairs, and dermabrasion. Additionally, as a first measure of hemostasis, we recommend H2O2 soaks immediately postoperatively in patients with active bleeding.

We have been utilizing this technique since H2O2 was described as an intraprocedural hemostatic agent during manual dermabrasion.3 Hydrogen peroxide is known to facilitate hemostasis with several accepted mechanisms that include regulating the contractility and barrier function of endothelial cells, activating latent cell surface tissue factor and platelet aggregation, and stimulating platelet-derived growth factor activation.4 It has been reported that increasing H2O2 levels leads to a dose-response increase in aggregation in the presence of subaggregating amounts of collagen.5 This concept was described in an article that utilizes H2O2 as a way to obtain hemostasis before skin grafting burn patients.6 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms h202, hydrogen peroxide, hemostasis, wound healing, surgery, and wound produced several surgical specialties—neurosurgery, orthopedics, gastroenterology, and maxillofacial surgery—that also utilize H2O2 as a hemostatic agent.7,8 One article described a dual-enzyme H2O2 generation machinery in hydrogels as a novel antimicrobial wound treatment.9

Practice Implications

The use of H2O2 as a topical hemostatic agent during surgery was described in 1984.2 The use of H2O2 is not suggested as a substitute for other strong and well-known hemostatic agents, such as aluminum chloride and ferric subsulfate, but rather as a technique that can be used in conjunction with standard methods of hemostasis and antisepsis. For surgical sites that are intended to be closed, we do not suggest these hemostatic agents, as they are known to be caustic, irritating, and pigmenting. In addition to H2O2’s known hemostatic and antiseptic properties, more recent literature invalidates wound impairment concerns and describes its possible role in signaling effector cells to respond downstream, contributing to tissue formation and remodeling.4 The use of H2O2 in wound and incision care has been controversial and avoided due to described skin irritation and possible premature removal of suture10; however, positive biochemical effects of H2O2 on acute wounds have been reported and dispel arguments that this agent causes tissue damage.4 Contrary to the traditional viewpoint that H2O2 probably impairs tissue through its high oxidative property, a proper level of H2O2 is considered an important requirement for normal wound healing. The report published in 1985 that raised concerns of H2O2 causing impaired wound healing through its effect on fibroblasts has been challenged given that the killed cultured fibroblasts were in an in vitro model and not likely representative of the complexities of a healing wound.10 In our experience, the use of H2O2 has not demonstrated any impairments or delays in wound healing, and we postulate that the exposure to H2O2 as described in our technique is not sufficient to cause notable impairment in fibroblast function in vivo. In addition, the role of H2O2 promoting oxidative stress as well as resolving inflammation may suggest it serves as a bidirectional regulator.

Future Directions

Additional studies are needed to assess this precise balance of H2O2 forming a favorable microenvironment in wounds. Similarly, although we discuss minimal and brief use of H2O2 during a procedure, the lack of data on the role of H2O2 as a prophylactic anti-infective agent for postoperative wound care also may be an area of future exploration.

- Henley J, Brewer JD. Newer hemostatic agents used in the practice of dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Res Pract. 2013;2013:279289.

- Hankin FM, Campbell SE, Goldstein SA, et al. Hydrogen peroxide as a topical hemostatic agent. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;186:244-247.

- Weiss J, Winkleman FJ, Titone A, et al. Evaluation of hydrogen peroxide as an intraprocedural hemostatic agent in manual dermabrasion. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1601-1603.

- Zhu G, Wang Q, Lu S, et al. Hydrogen peroxide: a potential wound therapeutic target? Med Princ Pract. 2017;26:301-308.

- Practicò D, Iuliano L, Ghiselli A, et al. Hydrogen peroxide as trigger of platelet aggregation. Haemostasis. 1991;21:169-174.

- Potyondy L, Lottenberg L, Anderson J, et al. The use of hydrogen peroxide for achieving dermal hemostasis after burn excision in a patient with platelet dysfunction. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27:99-101.

- Mawk JR. Hydrogen peroxide for hemostasis. Neurosurgery. 1986;18:827.

- Arakeri G, Brennan PA. Povidone-iodine and hydrogen peroxide mixture soaked gauze pack: a novel hemostatic technique. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71:1833.e1-1833.e3.

- Huber D, Tegl G, Mensah A, et al. A dual-enzyme hydrogen peroxide generation machinery in hydrogels supports antimicrobial wound treatment. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9:15307-15316.

- Lineaweaver W, McMorris S, Soucy D, et al. Cellular and bacterial toxicities of topical antimicrobials. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;75:394-396.

- Henley J, Brewer JD. Newer hemostatic agents used in the practice of dermatologic surgery. Dermatol Res Pract. 2013;2013:279289.

- Hankin FM, Campbell SE, Goldstein SA, et al. Hydrogen peroxide as a topical hemostatic agent. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;186:244-247.

- Weiss J, Winkleman FJ, Titone A, et al. Evaluation of hydrogen peroxide as an intraprocedural hemostatic agent in manual dermabrasion. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1601-1603.

- Zhu G, Wang Q, Lu S, et al. Hydrogen peroxide: a potential wound therapeutic target? Med Princ Pract. 2017;26:301-308.

- Practicò D, Iuliano L, Ghiselli A, et al. Hydrogen peroxide as trigger of platelet aggregation. Haemostasis. 1991;21:169-174.

- Potyondy L, Lottenberg L, Anderson J, et al. The use of hydrogen peroxide for achieving dermal hemostasis after burn excision in a patient with platelet dysfunction. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27:99-101.

- Mawk JR. Hydrogen peroxide for hemostasis. Neurosurgery. 1986;18:827.

- Arakeri G, Brennan PA. Povidone-iodine and hydrogen peroxide mixture soaked gauze pack: a novel hemostatic technique. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71:1833.e1-1833.e3.

- Huber D, Tegl G, Mensah A, et al. A dual-enzyme hydrogen peroxide generation machinery in hydrogels supports antimicrobial wound treatment. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9:15307-15316.

- Lineaweaver W, McMorris S, Soucy D, et al. Cellular and bacterial toxicities of topical antimicrobials. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;75:394-396.

Chromoblastomycosis Infection From a House Plant

To the Editor:

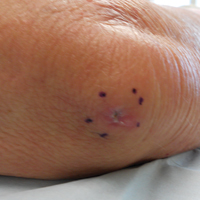

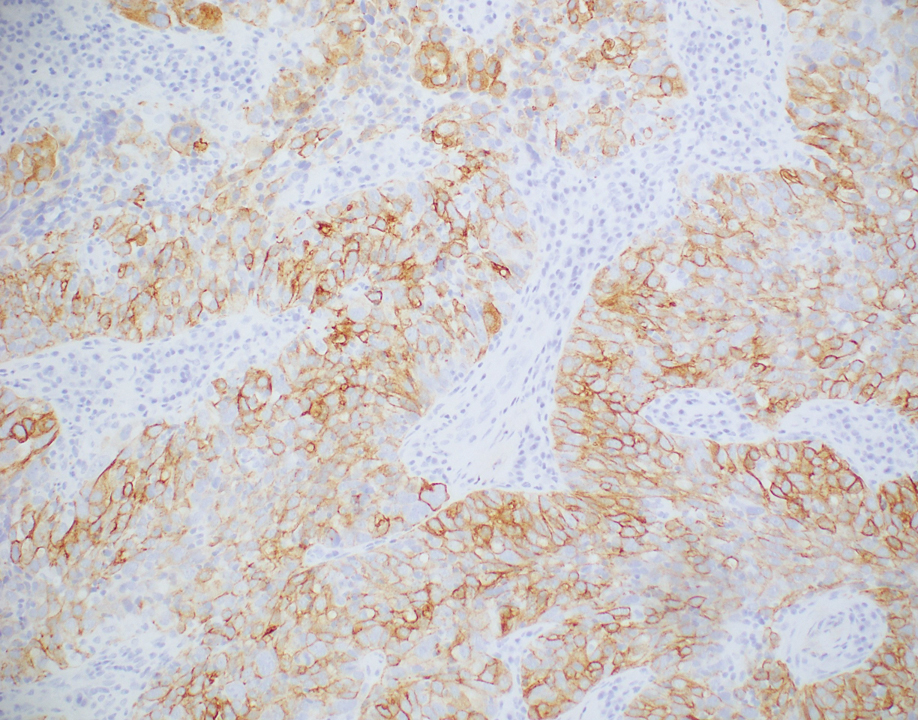

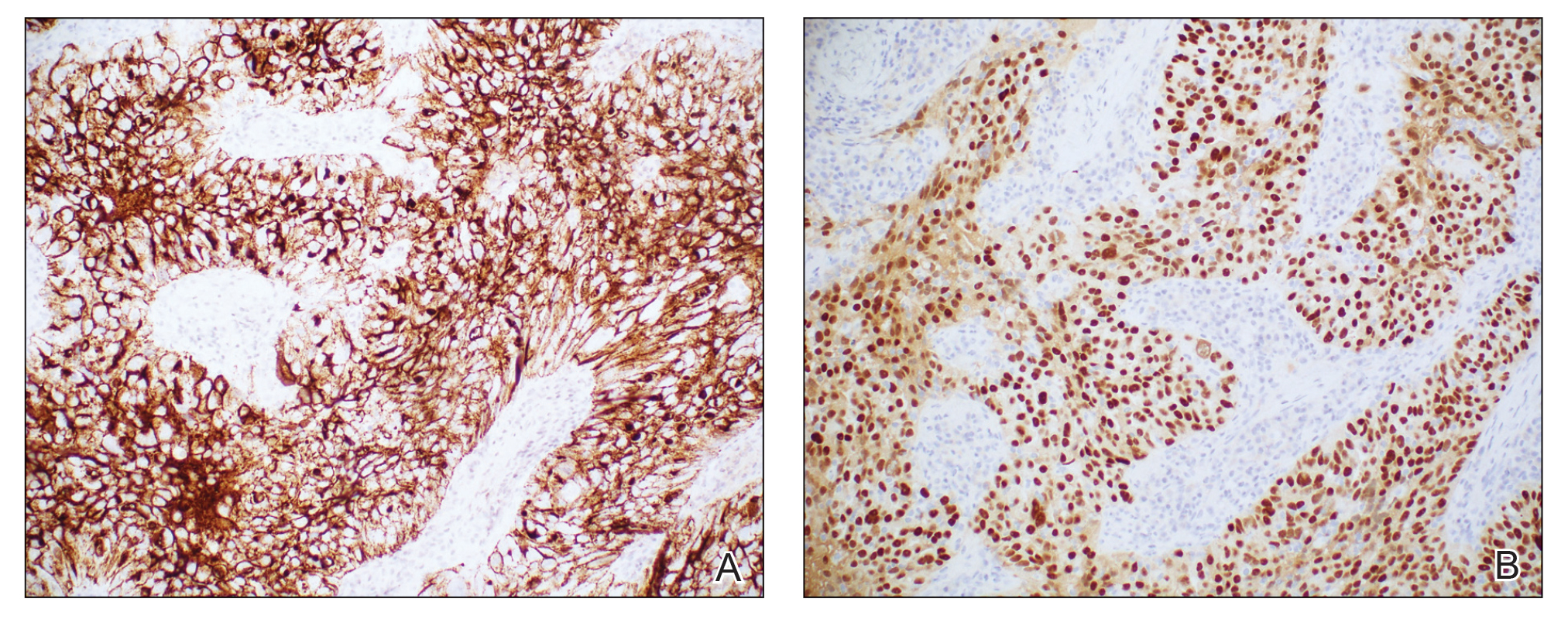

A 69-year-old woman with no history of immunodeficiency presented 1 month after a thorn from her locally grown Madagascar palm plant (Pachypodium lamerei) pierced the skin. The patient developed a painful nodule at the site on the left elbow (Figure 1). An excisional biopsy by an outside dermatologist was performed, which showed granulomatous inflammation within the dermis with epidermal hyperplasia and the presence of golden brown spherules (medlar bodies). The diagnosis was a dermal fungal infection consistent with chromoblastomycosis. A curative surgical excision was performed, and medlar bodies were seen adjacent to a polarizable foreign body consistent with plant material on histology (Figure 2). Because the lesion was localized, adjuvant medical treatment was not deemed necessary. The patient has not had any recurrence in the last 1.5 years since the resection.

The categorization of chromoblastomycosis includes a chronic fungal infection of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi. This definition is such that there are a multitude of organisms that can be the primary cause of this diagnosis. Generally, infection follows a traumatic permeation of the skin by a foreign body contaminated by the causative organism in agricultural workers. The most common dematiaceous pathogens are Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Phialophora verrucosa, and Cladosporium carrionii; however, the specific causative organism varies heavily on geographic location. With inoculation by a foreign body, a small papule develops at the site of the lesion. Several years after the primary infection, nodules and verrucous erythematous plaques develop in the same area, and patients present with concerns of pain and pruritus.1 Lesions usually are localized to the initial area of inoculation, generally a break in the skin by the offending foreign body, on the legs, arms, or hands, but hematogenous or lymphatic dissemination with distant transmission due to scratching also can occur. Ulceration due to secondary bacterial infection is another possible manifestation, resulting in a foul odor and less commonly lymphedema. Rarely, squamous cell carcinoma is a complication.2

RELATED ARTICLE: Fungal Foes: Presentations of Chromoblastomycosis Post–Hurricane Ike

On histopathology, thick-walled sclerotic bodies termed medlar bodies or copper pennies are pathognomonic for chromoblastomycosis and represent the fungal elements. Grossly, black dots can be seen on the skin in the affected areas from the transepidermal elimination of the fungi.1,2 However, there is no specificity for determining the causative organism in this manner, or even with culture, as it is difficult to differentiate the species morphologically. More advanced tests can help, such as polymerase chain reaction or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, where available.2 Hematoxylin and eosin stain also shows epidermal hyperplasia and dermal mononuclear infiltrate.

Treatment modalities include surgical excision, cryotherapy, pharmacologic treatment, and combination therapy. Localized lesions often can be resected, but more severe infections can require pharmacologic treatment. Unfortunately, there tends to be a high risk for relapse with most antifungal modalities. The combination of itraconazole and terbinafine has been shown to offer the best medical therapy with lower risk for refractoriness to treatment by producing a synergistic effect between the 2 antifungals.2,3 Many surgical treatments often are combined with oral antifungals to try to attain complete eradication in deep or extensive lesions, as seen in a case in which oral terbinafine was used prior to surgery to reduce the size of the lesion, followed by complete resection.4 With localized lesions that are resectable, a wide and deep incision often can be curative. Cryotherapy also may be coupled with surgical excision or pharmacologic therapy. Most literature suggests that cryotherapy or the use of antifungals prior to excision offers improved outcomes.2,5 Prognosis tends to be good for chromoblastomycoses, particularly with smaller lesions. Complete eradication varies greatly on the size and depth of the lesion, independent of the causative pathogen.

Our patient’s presentation with chromoblastomycosis is unique because of the source of infection, which was a plant grown from seeds in a local nursery in South Florida and then sold to the patient. The majority of chromoblastomycosis infections occur in agricultural workers, typically in tropical climates such as South and Central America, the Caribbean, and Mexico.1,2 Historically, infections in the United States have been uncommon, with the majority presenting in patients on prolonged corticosteroid therapy or with other immunosuppressive conditions.6,7

- Torres-Guerrero E, Isa-Isa R, Isa M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:403-408.

- Ameen M. Managing chromoblastomycosis. Trop Doct. 2010;40:65-67.

- Zhang J, Xi L, Lu C, et al. Successful treatment for chromoblastomycosis caused by Fonsecaea monophora: a report of three cases in Guangdong, China. Mycoses. 2009;52:176-181.

- Tamura K, Matsuyama T, Yahagi E, et al. A case of chromomycosis treated by surgical therapy combined with preceded oral administration of terbinafine to reduce the size of the lesion. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2012;37:6-10.

- Patel U, Chu J, Patel R, et al. Subcutaneous dematiaceous fungal infection. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:19.

- Basílio FM, Hammerschmidt M, Mukai MM, et al. Mucormycosis and chromoblastomycosis occurring in a patient with leprosy type 2 reaction under prolonged corticosteroid and thalidomide therapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:767-771.

- Parente JN, Talhari C, Ginter-Hanselmayer G, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis in immunocompetent patients: two new cases caused by Exophiala jeanselmei and Cladophialophora carrionii. Mycoses. 2001;54:265-269.

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old woman with no history of immunodeficiency presented 1 month after a thorn from her locally grown Madagascar palm plant (Pachypodium lamerei) pierced the skin. The patient developed a painful nodule at the site on the left elbow (Figure 1). An excisional biopsy by an outside dermatologist was performed, which showed granulomatous inflammation within the dermis with epidermal hyperplasia and the presence of golden brown spherules (medlar bodies). The diagnosis was a dermal fungal infection consistent with chromoblastomycosis. A curative surgical excision was performed, and medlar bodies were seen adjacent to a polarizable foreign body consistent with plant material on histology (Figure 2). Because the lesion was localized, adjuvant medical treatment was not deemed necessary. The patient has not had any recurrence in the last 1.5 years since the resection.

The categorization of chromoblastomycosis includes a chronic fungal infection of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi. This definition is such that there are a multitude of organisms that can be the primary cause of this diagnosis. Generally, infection follows a traumatic permeation of the skin by a foreign body contaminated by the causative organism in agricultural workers. The most common dematiaceous pathogens are Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Phialophora verrucosa, and Cladosporium carrionii; however, the specific causative organism varies heavily on geographic location. With inoculation by a foreign body, a small papule develops at the site of the lesion. Several years after the primary infection, nodules and verrucous erythematous plaques develop in the same area, and patients present with concerns of pain and pruritus.1 Lesions usually are localized to the initial area of inoculation, generally a break in the skin by the offending foreign body, on the legs, arms, or hands, but hematogenous or lymphatic dissemination with distant transmission due to scratching also can occur. Ulceration due to secondary bacterial infection is another possible manifestation, resulting in a foul odor and less commonly lymphedema. Rarely, squamous cell carcinoma is a complication.2

RELATED ARTICLE: Fungal Foes: Presentations of Chromoblastomycosis Post–Hurricane Ike

On histopathology, thick-walled sclerotic bodies termed medlar bodies or copper pennies are pathognomonic for chromoblastomycosis and represent the fungal elements. Grossly, black dots can be seen on the skin in the affected areas from the transepidermal elimination of the fungi.1,2 However, there is no specificity for determining the causative organism in this manner, or even with culture, as it is difficult to differentiate the species morphologically. More advanced tests can help, such as polymerase chain reaction or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, where available.2 Hematoxylin and eosin stain also shows epidermal hyperplasia and dermal mononuclear infiltrate.

Treatment modalities include surgical excision, cryotherapy, pharmacologic treatment, and combination therapy. Localized lesions often can be resected, but more severe infections can require pharmacologic treatment. Unfortunately, there tends to be a high risk for relapse with most antifungal modalities. The combination of itraconazole and terbinafine has been shown to offer the best medical therapy with lower risk for refractoriness to treatment by producing a synergistic effect between the 2 antifungals.2,3 Many surgical treatments often are combined with oral antifungals to try to attain complete eradication in deep or extensive lesions, as seen in a case in which oral terbinafine was used prior to surgery to reduce the size of the lesion, followed by complete resection.4 With localized lesions that are resectable, a wide and deep incision often can be curative. Cryotherapy also may be coupled with surgical excision or pharmacologic therapy. Most literature suggests that cryotherapy or the use of antifungals prior to excision offers improved outcomes.2,5 Prognosis tends to be good for chromoblastomycoses, particularly with smaller lesions. Complete eradication varies greatly on the size and depth of the lesion, independent of the causative pathogen.

Our patient’s presentation with chromoblastomycosis is unique because of the source of infection, which was a plant grown from seeds in a local nursery in South Florida and then sold to the patient. The majority of chromoblastomycosis infections occur in agricultural workers, typically in tropical climates such as South and Central America, the Caribbean, and Mexico.1,2 Historically, infections in the United States have been uncommon, with the majority presenting in patients on prolonged corticosteroid therapy or with other immunosuppressive conditions.6,7

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old woman with no history of immunodeficiency presented 1 month after a thorn from her locally grown Madagascar palm plant (Pachypodium lamerei) pierced the skin. The patient developed a painful nodule at the site on the left elbow (Figure 1). An excisional biopsy by an outside dermatologist was performed, which showed granulomatous inflammation within the dermis with epidermal hyperplasia and the presence of golden brown spherules (medlar bodies). The diagnosis was a dermal fungal infection consistent with chromoblastomycosis. A curative surgical excision was performed, and medlar bodies were seen adjacent to a polarizable foreign body consistent with plant material on histology (Figure 2). Because the lesion was localized, adjuvant medical treatment was not deemed necessary. The patient has not had any recurrence in the last 1.5 years since the resection.

The categorization of chromoblastomycosis includes a chronic fungal infection of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi. This definition is such that there are a multitude of organisms that can be the primary cause of this diagnosis. Generally, infection follows a traumatic permeation of the skin by a foreign body contaminated by the causative organism in agricultural workers. The most common dematiaceous pathogens are Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Phialophora verrucosa, and Cladosporium carrionii; however, the specific causative organism varies heavily on geographic location. With inoculation by a foreign body, a small papule develops at the site of the lesion. Several years after the primary infection, nodules and verrucous erythematous plaques develop in the same area, and patients present with concerns of pain and pruritus.1 Lesions usually are localized to the initial area of inoculation, generally a break in the skin by the offending foreign body, on the legs, arms, or hands, but hematogenous or lymphatic dissemination with distant transmission due to scratching also can occur. Ulceration due to secondary bacterial infection is another possible manifestation, resulting in a foul odor and less commonly lymphedema. Rarely, squamous cell carcinoma is a complication.2

RELATED ARTICLE: Fungal Foes: Presentations of Chromoblastomycosis Post–Hurricane Ike

On histopathology, thick-walled sclerotic bodies termed medlar bodies or copper pennies are pathognomonic for chromoblastomycosis and represent the fungal elements. Grossly, black dots can be seen on the skin in the affected areas from the transepidermal elimination of the fungi.1,2 However, there is no specificity for determining the causative organism in this manner, or even with culture, as it is difficult to differentiate the species morphologically. More advanced tests can help, such as polymerase chain reaction or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, where available.2 Hematoxylin and eosin stain also shows epidermal hyperplasia and dermal mononuclear infiltrate.

Treatment modalities include surgical excision, cryotherapy, pharmacologic treatment, and combination therapy. Localized lesions often can be resected, but more severe infections can require pharmacologic treatment. Unfortunately, there tends to be a high risk for relapse with most antifungal modalities. The combination of itraconazole and terbinafine has been shown to offer the best medical therapy with lower risk for refractoriness to treatment by producing a synergistic effect between the 2 antifungals.2,3 Many surgical treatments often are combined with oral antifungals to try to attain complete eradication in deep or extensive lesions, as seen in a case in which oral terbinafine was used prior to surgery to reduce the size of the lesion, followed by complete resection.4 With localized lesions that are resectable, a wide and deep incision often can be curative. Cryotherapy also may be coupled with surgical excision or pharmacologic therapy. Most literature suggests that cryotherapy or the use of antifungals prior to excision offers improved outcomes.2,5 Prognosis tends to be good for chromoblastomycoses, particularly with smaller lesions. Complete eradication varies greatly on the size and depth of the lesion, independent of the causative pathogen.

Our patient’s presentation with chromoblastomycosis is unique because of the source of infection, which was a plant grown from seeds in a local nursery in South Florida and then sold to the patient. The majority of chromoblastomycosis infections occur in agricultural workers, typically in tropical climates such as South and Central America, the Caribbean, and Mexico.1,2 Historically, infections in the United States have been uncommon, with the majority presenting in patients on prolonged corticosteroid therapy or with other immunosuppressive conditions.6,7

- Torres-Guerrero E, Isa-Isa R, Isa M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:403-408.

- Ameen M. Managing chromoblastomycosis. Trop Doct. 2010;40:65-67.

- Zhang J, Xi L, Lu C, et al. Successful treatment for chromoblastomycosis caused by Fonsecaea monophora: a report of three cases in Guangdong, China. Mycoses. 2009;52:176-181.

- Tamura K, Matsuyama T, Yahagi E, et al. A case of chromomycosis treated by surgical therapy combined with preceded oral administration of terbinafine to reduce the size of the lesion. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2012;37:6-10.

- Patel U, Chu J, Patel R, et al. Subcutaneous dematiaceous fungal infection. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:19.

- Basílio FM, Hammerschmidt M, Mukai MM, et al. Mucormycosis and chromoblastomycosis occurring in a patient with leprosy type 2 reaction under prolonged corticosteroid and thalidomide therapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:767-771.

- Parente JN, Talhari C, Ginter-Hanselmayer G, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis in immunocompetent patients: two new cases caused by Exophiala jeanselmei and Cladophialophora carrionii. Mycoses. 2001;54:265-269.

- Torres-Guerrero E, Isa-Isa R, Isa M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:403-408.

- Ameen M. Managing chromoblastomycosis. Trop Doct. 2010;40:65-67.

- Zhang J, Xi L, Lu C, et al. Successful treatment for chromoblastomycosis caused by Fonsecaea monophora: a report of three cases in Guangdong, China. Mycoses. 2009;52:176-181.

- Tamura K, Matsuyama T, Yahagi E, et al. A case of chromomycosis treated by surgical therapy combined with preceded oral administration of terbinafine to reduce the size of the lesion. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2012;37:6-10.

- Patel U, Chu J, Patel R, et al. Subcutaneous dematiaceous fungal infection. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:19.

- Basílio FM, Hammerschmidt M, Mukai MM, et al. Mucormycosis and chromoblastomycosis occurring in a patient with leprosy type 2 reaction under prolonged corticosteroid and thalidomide therapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:767-771.

- Parente JN, Talhari C, Ginter-Hanselmayer G, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis in immunocompetent patients: two new cases caused by Exophiala jeanselmei and Cladophialophora carrionii. Mycoses. 2001;54:265-269.

Practice Points

- Chromoblastomycosis is an uncommon fungal infection that should be considered in cases of traumatic injuries to the skin.

- Biopsies of growing or nonhealing nodules will demonstrate characteristic golden brown spherules (medlar bodies).

- In localized cases, surgical excision may be curative.