User login

Effect of COVID-19 Vaccination on Disease Severity in Patients With Stable Plaque Psoriasis: A Cross-sectional Study

To the Editor:

COVID-19 infection has resulted in 6.9 million deaths worldwide. India has the third highest mortality from COVID-19 infection after the United States and Brazil.1 Vaccination plays a crucial role in containing COVID-19 infection and reducing its severity. At present, 11 vaccines have been approved by the World Health Organization. India started its vaccination program on January 16, 2021, with approval for use of Covaxin (Bharat Biotech) and Covishield (Oxford/AstraZeneca formulation)(Serum Institute of India). More than 2 billion doses have been administered since then.2,3

Patients with psoriasis are prone to develop a severe form of COVID-19 due to comorbidities and the intake of immunosuppressive drugs.4 These patients often are hesitant to receive the vaccine without an expert opinion. COVID-19 vaccines are considered to increase tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells. Tumor necrosis factor α is a key proinflammatory cytokine implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccines induce elevation of IL-6 and helper T cells (TH17), which can induce a flare of psoriasis in a subset of patients.5The International Psoriasis Council recommends that patients with psoriasis receive one of the vaccines approved to prevent COVID-19 infection as soon as possible.6 Reports of new-onset psoriasis and flare of psoriasis after the use of COVID-19 vaccines, such as those manufactured by Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, and AstraZeneca, have been published from different parts of the world.7 India used locally developed whole virion inactivated BBV152 (Covaxin) and nonreplicating viral vaccine ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (Covishield) in its vaccination program and exported them to other developing countries. There is a dearth of data on the safety of these vaccines in patients with psoriasis, which needs to be assessed. Later, Covaxin, ZyCoV-D (DNA plasmid vaccine; Cadila Healthcare), and CorbeVax (protein subunit vaccine; Biological E) were approved for usage in children.8 We conducted a cross-sectional study using the direct interview method.

Patients with psoriasis who attended the outpatient department of the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (Chandigarh, India) from April 2022 to June 2022 were invited to participate in the study after written informed consent was received. Patients 18 years and older with chronic plaque psoriasis who had received a COVID-19 vaccine dose in the last 90 days were enrolled. Data on demographics, comorbidities, treatment received for psoriasis, vaccination concerns, history of COVID-19 infection, type of vaccine received with doses, adverse effects, and psoriasis flare after receiving the vaccine (considered up to 2 weeks from the date of vaccination) were collected. Ordinal logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with a psoriasis flare following vaccination. P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

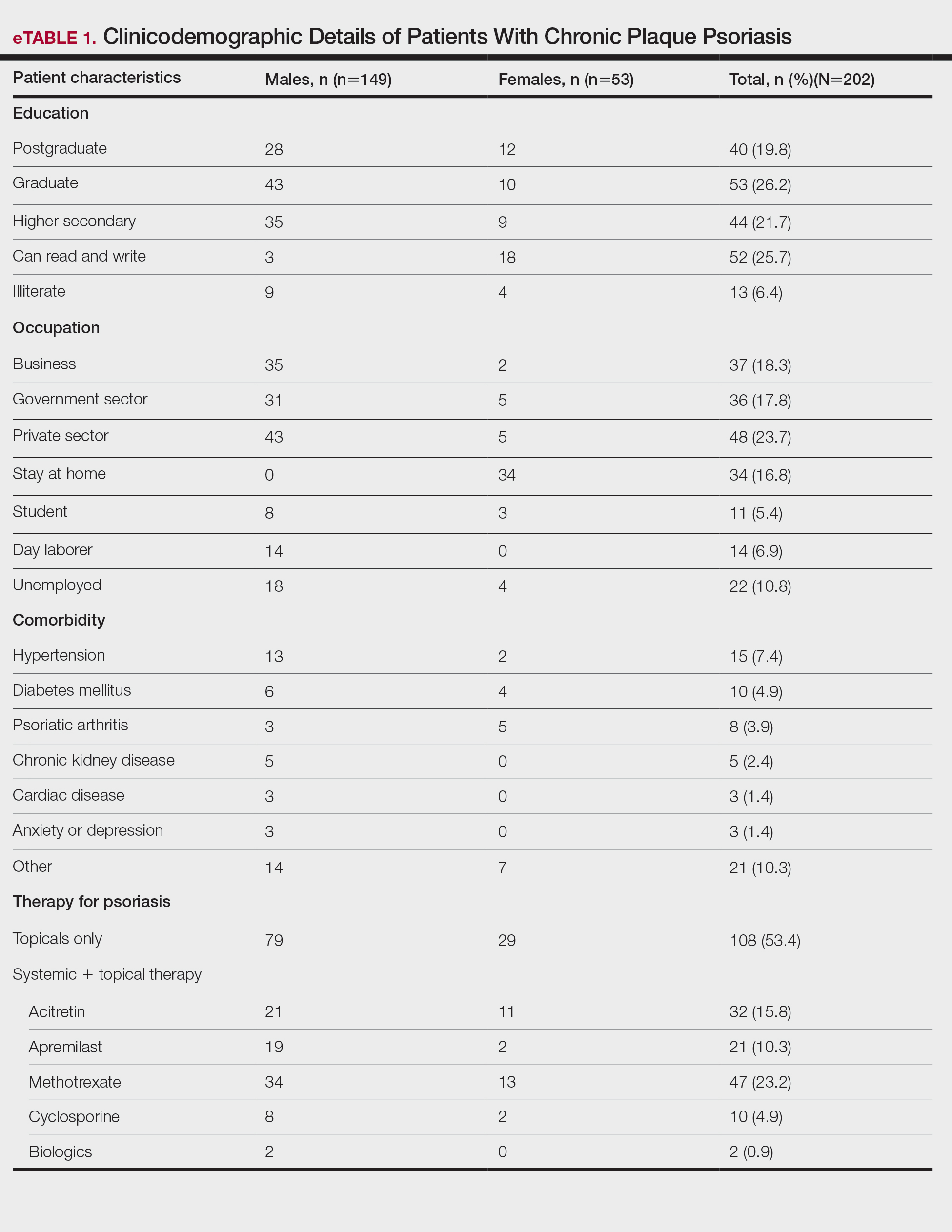

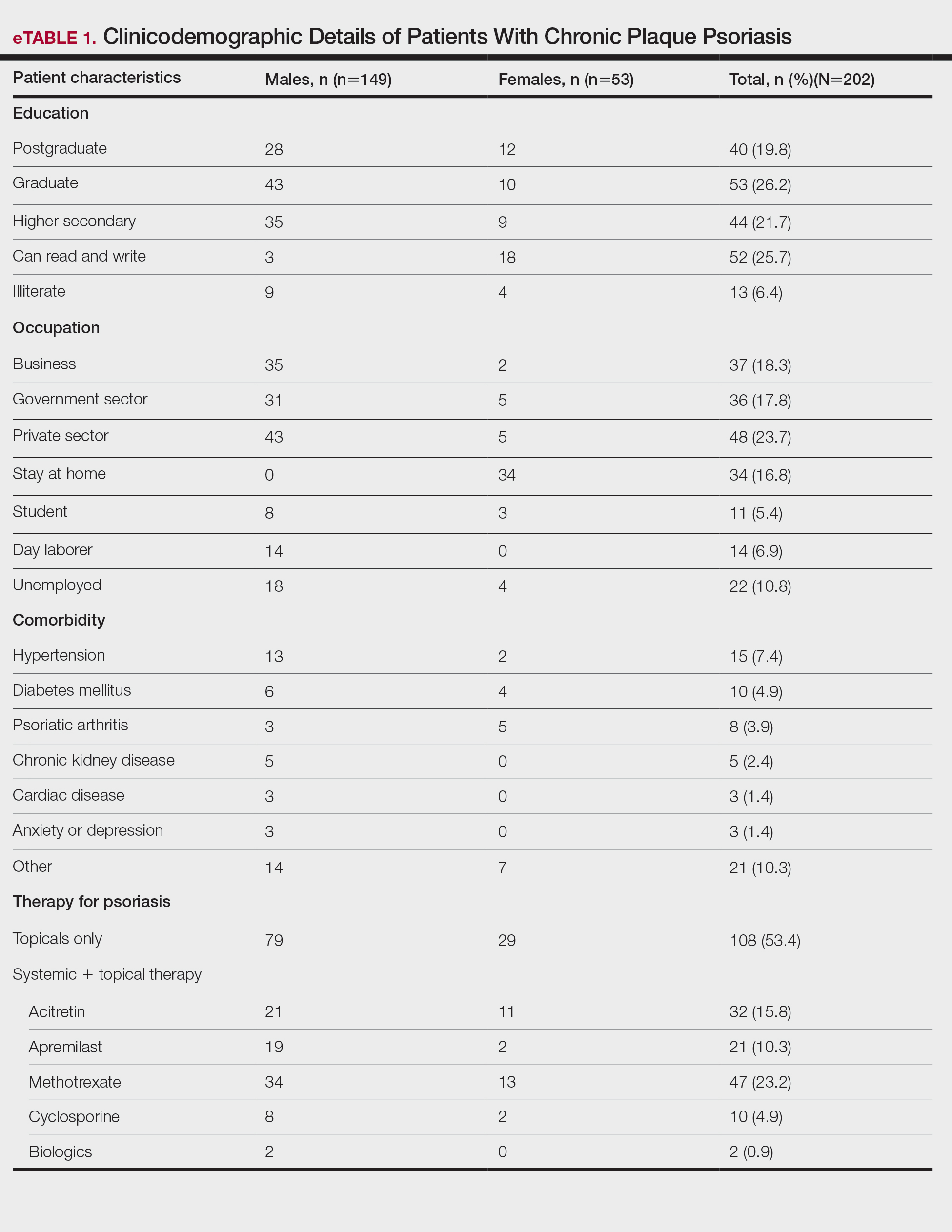

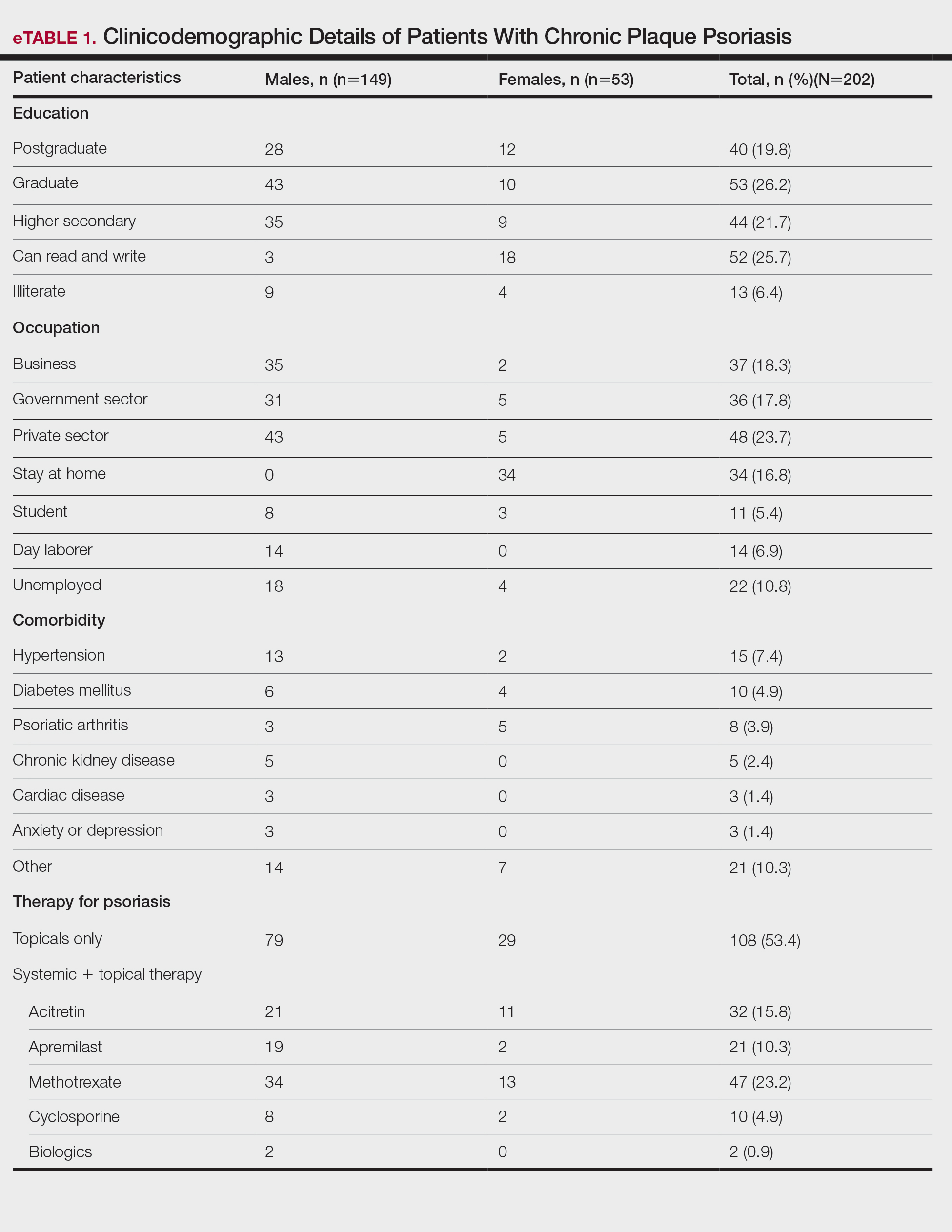

A total of 202 patients with chronic plaque psoriasis who received either Covaxin or Covishield were enrolled during the study period. The mean age (SD) was 40.3 (13.1) years, and 149 (73.8%) patients were male. One hundred thirty-five (66.8%) patients completed 2 doses of the vaccine. eTable 1 provides the clinicodemographic details of the patients. Eighty-three (41.1%) patients had a fear of psoriasis flare after vaccination. Seventy-two (35.6%) patients received the vaccine after clearance from their treating physician/dermatologist. One hundred sixty-four (81.2%) patients received the Covishield vaccine, and 38 (18.8%) patients received Covaxin. Eighty-three (41.1%) patients reported flulike symptoms, such as fever, myalgia, or body pain, within the first week of vaccination. Sixty-one (30.2%) patients reported a psoriasis flare after vaccination in the form of new lesions or worsening of pre-existing lesions. Of these patients, 51 reported a flare after receiving the first dose of vaccine, 8 patients reported a flare after receiving the second dose of vaccine, and 2 patients reported a flare after receiving both doses of vaccine. The mean (SD) flare onset was 8.1 (3.4) days after the vaccination. Eighteen patients considered the flare to be severe. Seventeen (8.4%) patients reported a positive history of COVID-19 infection before vaccination. None of the patients reported breakthrough COVID-19 infection or pustular aggravation of psoriasis following the vaccination.

The self-reported psoriasis flare after receiving the COVID-19 vaccine was significantly higher in patients who experienced immediate adverse effects (P=.005), which included fever, myalgia, joint pain, and injection-site reaction. The reported postvaccination psoriasis flare was not significantly associated with patient sex, history of COVID-19 infection, type of vaccine received, comorbidities, or therapy for psoriasis (eTable 2).

Nearly 30% of our patients reported a postvaccination psoriasis flare, which was more common after the first vaccine dose. Sotiriou et al7 reported 14 cases of psoriasis flare in patients after receiving Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, and AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines. These patients experienced an exacerbation of disease soon after the second dose of vaccine (mean [SD], 10.36 [7.71] days), and 21% of the 713 enrolled patients wanted to forego the immunization due to concern of a postvaccination psoriasis flare.7 In another report, 14 (27%) patients developed a psoriasis flare after COVID-19 vaccination; the mean (SD) flare onset was 9.3 (4.3) days after vaccination.9

Data on the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine in patients using immunosuppressive drugs are limited. We did not find a significant association between the psoriasis flare and use of immunosuppressive drugs or type of vaccine received. Huang and Tsai9 observed similar results, with no association between psoriasis flare and use of immunosuppressive drugs or biologics, while Damiani et al10 demonstrated a protective role of biologics in preventing vaccine-induced psoriasis flare.

Similar to another study from India,11 the immediate adverse effects due to immunization with Covaxin and Covishield were mild in our study and resolved within a week. The incidence of psoriasis flare was significantly higher in patients who reported adverse effects (P=.005). Activation of immune response after vaccination leads to the release of proinflammatory and pyrogenic cytokines (ie, IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α), which may explain the higher incidence of psoriasis flare in patients experiencing adverse effects to vaccination.12

Our study showed approximately 30% of patients developed a psoriasis flare after COVID-19 vaccination, with no patients experiencing any vaccine-related serious adverse events, which suggests that Covaxin and Covishield are safe for patients with psoriasis in India. Limitations of our study include potential inaccuracy of the patient’s self-assessment of symptoms and disease flare, recall bias that may lead to errors in estimating patient-reported outcomes, the flare of psoriasis potentially being a part of disease fluctuation, and flare being enhanced by the psychological stress of vaccination.

Considering a high risk for severe COVID-19 infection in patients with psoriasis with comorbidities and those using immunosuppressive drugs, Covaxin and Covishield can be safely recommended in India. However, caution needs to be exercised when vaccinating patients with an unstable disease or severe psoriasis.

- COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic: weekly trends. Worldometer. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

- National COVID-19 vaccination programme meets its goals by overcoming R&D and logistical challenges, says economic survey 2022-23. Government of India Press Information Bureau website. Published January 31, 2023. Accessed August 24, 2023. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1894907

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. CoWIN. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.cowin.gov.in/

- Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE, et al. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2021;397:1301-1315.

- Wu D, Yang XO. TH17 responses in cytokine storm of COVID-19: anemerging target of JAK2 inhibitor fedratinib. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53:368-370.

- International Psoriasis Council. Revised IPC statement on COVID-19. Published December 19, 2022. Accessed August 24, 2023. https://psoriasiscouncil.org/covid-19/revised-statement-covid-19/

- Sotiriou E, Tsentemeidou A, Bakirtzi K, et al. Psoriasis exacerbation after COVID-19 vaccination: a report of 14 cases from a single centre. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:E857-E859.

- Kaul R. India clears 2 vaccines for kids under 12 years. Hindustan Times. Published April 27, 2022. Accessed August 24, 2023. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/india-clears-2-vaccines-for-kids-under-12-years-101650998027336.html

- Huang YW, Tsai TF. Exacerbation of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination: report from a single center. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:812010.

- Damiani G, Allocco F, Young Dermatologists Italian Network, et al. COVID-19 vaccination and patients with psoriasis under biologics: real-life evidence on safety and effectiveness from Italian vaccinated healthcare workers. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;460:1106-1108.

- Joshi RK, Muralidharan CG, Gulati DS, et al. Higher incidence of reported adverse events following immunisation (AEFI) after first dose of COVID-19 vaccine among previously infected health care workers. Med J Armed Forces India. 2021;77(suppl 2):S505-S507.

- Hervé C, Laupèze B, Del Giudice G, et al. The how’s and what’s of vaccine reactogenicity. NPJ Vaccines. 2019;4:39.

To the Editor:

COVID-19 infection has resulted in 6.9 million deaths worldwide. India has the third highest mortality from COVID-19 infection after the United States and Brazil.1 Vaccination plays a crucial role in containing COVID-19 infection and reducing its severity. At present, 11 vaccines have been approved by the World Health Organization. India started its vaccination program on January 16, 2021, with approval for use of Covaxin (Bharat Biotech) and Covishield (Oxford/AstraZeneca formulation)(Serum Institute of India). More than 2 billion doses have been administered since then.2,3

Patients with psoriasis are prone to develop a severe form of COVID-19 due to comorbidities and the intake of immunosuppressive drugs.4 These patients often are hesitant to receive the vaccine without an expert opinion. COVID-19 vaccines are considered to increase tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells. Tumor necrosis factor α is a key proinflammatory cytokine implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccines induce elevation of IL-6 and helper T cells (TH17), which can induce a flare of psoriasis in a subset of patients.5The International Psoriasis Council recommends that patients with psoriasis receive one of the vaccines approved to prevent COVID-19 infection as soon as possible.6 Reports of new-onset psoriasis and flare of psoriasis after the use of COVID-19 vaccines, such as those manufactured by Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, and AstraZeneca, have been published from different parts of the world.7 India used locally developed whole virion inactivated BBV152 (Covaxin) and nonreplicating viral vaccine ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (Covishield) in its vaccination program and exported them to other developing countries. There is a dearth of data on the safety of these vaccines in patients with psoriasis, which needs to be assessed. Later, Covaxin, ZyCoV-D (DNA plasmid vaccine; Cadila Healthcare), and CorbeVax (protein subunit vaccine; Biological E) were approved for usage in children.8 We conducted a cross-sectional study using the direct interview method.

Patients with psoriasis who attended the outpatient department of the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (Chandigarh, India) from April 2022 to June 2022 were invited to participate in the study after written informed consent was received. Patients 18 years and older with chronic plaque psoriasis who had received a COVID-19 vaccine dose in the last 90 days were enrolled. Data on demographics, comorbidities, treatment received for psoriasis, vaccination concerns, history of COVID-19 infection, type of vaccine received with doses, adverse effects, and psoriasis flare after receiving the vaccine (considered up to 2 weeks from the date of vaccination) were collected. Ordinal logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with a psoriasis flare following vaccination. P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 202 patients with chronic plaque psoriasis who received either Covaxin or Covishield were enrolled during the study period. The mean age (SD) was 40.3 (13.1) years, and 149 (73.8%) patients were male. One hundred thirty-five (66.8%) patients completed 2 doses of the vaccine. eTable 1 provides the clinicodemographic details of the patients. Eighty-three (41.1%) patients had a fear of psoriasis flare after vaccination. Seventy-two (35.6%) patients received the vaccine after clearance from their treating physician/dermatologist. One hundred sixty-four (81.2%) patients received the Covishield vaccine, and 38 (18.8%) patients received Covaxin. Eighty-three (41.1%) patients reported flulike symptoms, such as fever, myalgia, or body pain, within the first week of vaccination. Sixty-one (30.2%) patients reported a psoriasis flare after vaccination in the form of new lesions or worsening of pre-existing lesions. Of these patients, 51 reported a flare after receiving the first dose of vaccine, 8 patients reported a flare after receiving the second dose of vaccine, and 2 patients reported a flare after receiving both doses of vaccine. The mean (SD) flare onset was 8.1 (3.4) days after the vaccination. Eighteen patients considered the flare to be severe. Seventeen (8.4%) patients reported a positive history of COVID-19 infection before vaccination. None of the patients reported breakthrough COVID-19 infection or pustular aggravation of psoriasis following the vaccination.

The self-reported psoriasis flare after receiving the COVID-19 vaccine was significantly higher in patients who experienced immediate adverse effects (P=.005), which included fever, myalgia, joint pain, and injection-site reaction. The reported postvaccination psoriasis flare was not significantly associated with patient sex, history of COVID-19 infection, type of vaccine received, comorbidities, or therapy for psoriasis (eTable 2).

Nearly 30% of our patients reported a postvaccination psoriasis flare, which was more common after the first vaccine dose. Sotiriou et al7 reported 14 cases of psoriasis flare in patients after receiving Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, and AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines. These patients experienced an exacerbation of disease soon after the second dose of vaccine (mean [SD], 10.36 [7.71] days), and 21% of the 713 enrolled patients wanted to forego the immunization due to concern of a postvaccination psoriasis flare.7 In another report, 14 (27%) patients developed a psoriasis flare after COVID-19 vaccination; the mean (SD) flare onset was 9.3 (4.3) days after vaccination.9

Data on the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine in patients using immunosuppressive drugs are limited. We did not find a significant association between the psoriasis flare and use of immunosuppressive drugs or type of vaccine received. Huang and Tsai9 observed similar results, with no association between psoriasis flare and use of immunosuppressive drugs or biologics, while Damiani et al10 demonstrated a protective role of biologics in preventing vaccine-induced psoriasis flare.

Similar to another study from India,11 the immediate adverse effects due to immunization with Covaxin and Covishield were mild in our study and resolved within a week. The incidence of psoriasis flare was significantly higher in patients who reported adverse effects (P=.005). Activation of immune response after vaccination leads to the release of proinflammatory and pyrogenic cytokines (ie, IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α), which may explain the higher incidence of psoriasis flare in patients experiencing adverse effects to vaccination.12

Our study showed approximately 30% of patients developed a psoriasis flare after COVID-19 vaccination, with no patients experiencing any vaccine-related serious adverse events, which suggests that Covaxin and Covishield are safe for patients with psoriasis in India. Limitations of our study include potential inaccuracy of the patient’s self-assessment of symptoms and disease flare, recall bias that may lead to errors in estimating patient-reported outcomes, the flare of psoriasis potentially being a part of disease fluctuation, and flare being enhanced by the psychological stress of vaccination.

Considering a high risk for severe COVID-19 infection in patients with psoriasis with comorbidities and those using immunosuppressive drugs, Covaxin and Covishield can be safely recommended in India. However, caution needs to be exercised when vaccinating patients with an unstable disease or severe psoriasis.

To the Editor:

COVID-19 infection has resulted in 6.9 million deaths worldwide. India has the third highest mortality from COVID-19 infection after the United States and Brazil.1 Vaccination plays a crucial role in containing COVID-19 infection and reducing its severity. At present, 11 vaccines have been approved by the World Health Organization. India started its vaccination program on January 16, 2021, with approval for use of Covaxin (Bharat Biotech) and Covishield (Oxford/AstraZeneca formulation)(Serum Institute of India). More than 2 billion doses have been administered since then.2,3

Patients with psoriasis are prone to develop a severe form of COVID-19 due to comorbidities and the intake of immunosuppressive drugs.4 These patients often are hesitant to receive the vaccine without an expert opinion. COVID-19 vaccines are considered to increase tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells. Tumor necrosis factor α is a key proinflammatory cytokine implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccines induce elevation of IL-6 and helper T cells (TH17), which can induce a flare of psoriasis in a subset of patients.5The International Psoriasis Council recommends that patients with psoriasis receive one of the vaccines approved to prevent COVID-19 infection as soon as possible.6 Reports of new-onset psoriasis and flare of psoriasis after the use of COVID-19 vaccines, such as those manufactured by Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, and AstraZeneca, have been published from different parts of the world.7 India used locally developed whole virion inactivated BBV152 (Covaxin) and nonreplicating viral vaccine ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (Covishield) in its vaccination program and exported them to other developing countries. There is a dearth of data on the safety of these vaccines in patients with psoriasis, which needs to be assessed. Later, Covaxin, ZyCoV-D (DNA plasmid vaccine; Cadila Healthcare), and CorbeVax (protein subunit vaccine; Biological E) were approved for usage in children.8 We conducted a cross-sectional study using the direct interview method.

Patients with psoriasis who attended the outpatient department of the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (Chandigarh, India) from April 2022 to June 2022 were invited to participate in the study after written informed consent was received. Patients 18 years and older with chronic plaque psoriasis who had received a COVID-19 vaccine dose in the last 90 days were enrolled. Data on demographics, comorbidities, treatment received for psoriasis, vaccination concerns, history of COVID-19 infection, type of vaccine received with doses, adverse effects, and psoriasis flare after receiving the vaccine (considered up to 2 weeks from the date of vaccination) were collected. Ordinal logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with a psoriasis flare following vaccination. P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 202 patients with chronic plaque psoriasis who received either Covaxin or Covishield were enrolled during the study period. The mean age (SD) was 40.3 (13.1) years, and 149 (73.8%) patients were male. One hundred thirty-five (66.8%) patients completed 2 doses of the vaccine. eTable 1 provides the clinicodemographic details of the patients. Eighty-three (41.1%) patients had a fear of psoriasis flare after vaccination. Seventy-two (35.6%) patients received the vaccine after clearance from their treating physician/dermatologist. One hundred sixty-four (81.2%) patients received the Covishield vaccine, and 38 (18.8%) patients received Covaxin. Eighty-three (41.1%) patients reported flulike symptoms, such as fever, myalgia, or body pain, within the first week of vaccination. Sixty-one (30.2%) patients reported a psoriasis flare after vaccination in the form of new lesions or worsening of pre-existing lesions. Of these patients, 51 reported a flare after receiving the first dose of vaccine, 8 patients reported a flare after receiving the second dose of vaccine, and 2 patients reported a flare after receiving both doses of vaccine. The mean (SD) flare onset was 8.1 (3.4) days after the vaccination. Eighteen patients considered the flare to be severe. Seventeen (8.4%) patients reported a positive history of COVID-19 infection before vaccination. None of the patients reported breakthrough COVID-19 infection or pustular aggravation of psoriasis following the vaccination.

The self-reported psoriasis flare after receiving the COVID-19 vaccine was significantly higher in patients who experienced immediate adverse effects (P=.005), which included fever, myalgia, joint pain, and injection-site reaction. The reported postvaccination psoriasis flare was not significantly associated with patient sex, history of COVID-19 infection, type of vaccine received, comorbidities, or therapy for psoriasis (eTable 2).

Nearly 30% of our patients reported a postvaccination psoriasis flare, which was more common after the first vaccine dose. Sotiriou et al7 reported 14 cases of psoriasis flare in patients after receiving Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, and AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccines. These patients experienced an exacerbation of disease soon after the second dose of vaccine (mean [SD], 10.36 [7.71] days), and 21% of the 713 enrolled patients wanted to forego the immunization due to concern of a postvaccination psoriasis flare.7 In another report, 14 (27%) patients developed a psoriasis flare after COVID-19 vaccination; the mean (SD) flare onset was 9.3 (4.3) days after vaccination.9

Data on the safety of the COVID-19 vaccine in patients using immunosuppressive drugs are limited. We did not find a significant association between the psoriasis flare and use of immunosuppressive drugs or type of vaccine received. Huang and Tsai9 observed similar results, with no association between psoriasis flare and use of immunosuppressive drugs or biologics, while Damiani et al10 demonstrated a protective role of biologics in preventing vaccine-induced psoriasis flare.

Similar to another study from India,11 the immediate adverse effects due to immunization with Covaxin and Covishield were mild in our study and resolved within a week. The incidence of psoriasis flare was significantly higher in patients who reported adverse effects (P=.005). Activation of immune response after vaccination leads to the release of proinflammatory and pyrogenic cytokines (ie, IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α), which may explain the higher incidence of psoriasis flare in patients experiencing adverse effects to vaccination.12

Our study showed approximately 30% of patients developed a psoriasis flare after COVID-19 vaccination, with no patients experiencing any vaccine-related serious adverse events, which suggests that Covaxin and Covishield are safe for patients with psoriasis in India. Limitations of our study include potential inaccuracy of the patient’s self-assessment of symptoms and disease flare, recall bias that may lead to errors in estimating patient-reported outcomes, the flare of psoriasis potentially being a part of disease fluctuation, and flare being enhanced by the psychological stress of vaccination.

Considering a high risk for severe COVID-19 infection in patients with psoriasis with comorbidities and those using immunosuppressive drugs, Covaxin and Covishield can be safely recommended in India. However, caution needs to be exercised when vaccinating patients with an unstable disease or severe psoriasis.

- COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic: weekly trends. Worldometer. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

- National COVID-19 vaccination programme meets its goals by overcoming R&D and logistical challenges, says economic survey 2022-23. Government of India Press Information Bureau website. Published January 31, 2023. Accessed August 24, 2023. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1894907

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. CoWIN. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.cowin.gov.in/

- Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE, et al. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2021;397:1301-1315.

- Wu D, Yang XO. TH17 responses in cytokine storm of COVID-19: anemerging target of JAK2 inhibitor fedratinib. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53:368-370.

- International Psoriasis Council. Revised IPC statement on COVID-19. Published December 19, 2022. Accessed August 24, 2023. https://psoriasiscouncil.org/covid-19/revised-statement-covid-19/

- Sotiriou E, Tsentemeidou A, Bakirtzi K, et al. Psoriasis exacerbation after COVID-19 vaccination: a report of 14 cases from a single centre. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:E857-E859.

- Kaul R. India clears 2 vaccines for kids under 12 years. Hindustan Times. Published April 27, 2022. Accessed August 24, 2023. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/india-clears-2-vaccines-for-kids-under-12-years-101650998027336.html

- Huang YW, Tsai TF. Exacerbation of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination: report from a single center. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:812010.

- Damiani G, Allocco F, Young Dermatologists Italian Network, et al. COVID-19 vaccination and patients with psoriasis under biologics: real-life evidence on safety and effectiveness from Italian vaccinated healthcare workers. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;460:1106-1108.

- Joshi RK, Muralidharan CG, Gulati DS, et al. Higher incidence of reported adverse events following immunisation (AEFI) after first dose of COVID-19 vaccine among previously infected health care workers. Med J Armed Forces India. 2021;77(suppl 2):S505-S507.

- Hervé C, Laupèze B, Del Giudice G, et al. The how’s and what’s of vaccine reactogenicity. NPJ Vaccines. 2019;4:39.

- COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic: weekly trends. Worldometer. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

- National COVID-19 vaccination programme meets its goals by overcoming R&D and logistical challenges, says economic survey 2022-23. Government of India Press Information Bureau website. Published January 31, 2023. Accessed August 24, 2023. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1894907

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. CoWIN. Accessed August 21, 2023. https://www.cowin.gov.in/

- Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE, et al. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2021;397:1301-1315.

- Wu D, Yang XO. TH17 responses in cytokine storm of COVID-19: anemerging target of JAK2 inhibitor fedratinib. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53:368-370.

- International Psoriasis Council. Revised IPC statement on COVID-19. Published December 19, 2022. Accessed August 24, 2023. https://psoriasiscouncil.org/covid-19/revised-statement-covid-19/

- Sotiriou E, Tsentemeidou A, Bakirtzi K, et al. Psoriasis exacerbation after COVID-19 vaccination: a report of 14 cases from a single centre. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:E857-E859.

- Kaul R. India clears 2 vaccines for kids under 12 years. Hindustan Times. Published April 27, 2022. Accessed August 24, 2023. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/india-clears-2-vaccines-for-kids-under-12-years-101650998027336.html

- Huang YW, Tsai TF. Exacerbation of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination: report from a single center. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:812010.

- Damiani G, Allocco F, Young Dermatologists Italian Network, et al. COVID-19 vaccination and patients with psoriasis under biologics: real-life evidence on safety and effectiveness from Italian vaccinated healthcare workers. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;460:1106-1108.

- Joshi RK, Muralidharan CG, Gulati DS, et al. Higher incidence of reported adverse events following immunisation (AEFI) after first dose of COVID-19 vaccine among previously infected health care workers. Med J Armed Forces India. 2021;77(suppl 2):S505-S507.

- Hervé C, Laupèze B, Del Giudice G, et al. The how’s and what’s of vaccine reactogenicity. NPJ Vaccines. 2019;4:39.

Practice Points

- Vaccines are known to induce a psoriasis flare.

- Given the high risk for severe COVID infection in individuals with psoriasis who have comorbidities, vaccination with Covaxin and Covishield can be safely recommended in India for this population.

Sudden Cardiac Death in a Young Patient With Psoriasis

To the Editor:

The evolution in the understanding of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis has unfolded many new facets of this immune-mediated inflammatory disease. Once considered to be just a cutaneous disease, psoriasis is not actually confined to skin but can involve almost any other system of the body. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality are the major concerns in patients with psoriasis. We report the sudden death of a young man with severe psoriasis.

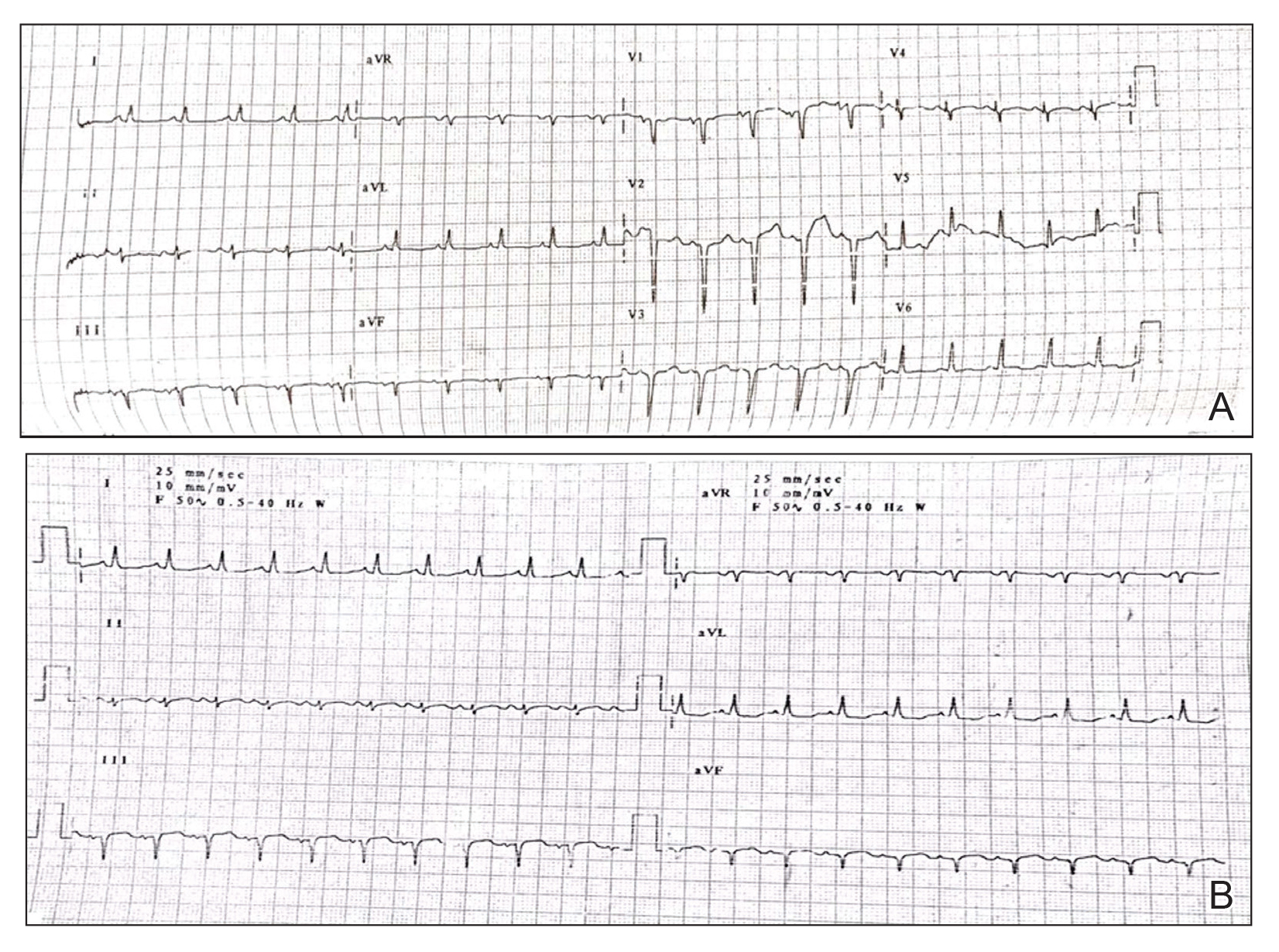

A 31-year-old man was admitted for severe psoriasis with pustular exacerbation (Figures 1A and 1B). He had moderate to severe unstable disease during the last 8 years and was managed with oral methotrexate (0.3–0.5 mg/kg/wk). He was not compliant with treatment, which led to multiple relapses. There was no personal or family history of risk factors for cardiovascular events (CVEs). At the time of present hospitalization, his vital parameters were normal. Physical examination revealed erythematous scaly plaques on more than 75% of the body surface area. Multiple pustules also were noted, often coalescing to form plaques (Figure 1C). Baseline investigations consisting of complete blood cell count, lipid profile, liver and renal functions, and chest radiography were within reference range. Baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) at admission was unremarkable (Figure 2A), except for sinus tachycardia. Low-voltage complexes in limb leads were appreciated as well as a corrected QT interval of 420 milliseconds (within reference range). Echocardiography was normal (visual ejection fraction of 60%).

The patient was unable to tolerate methotrexate due to excessive nausea; he was started on oral acitretin 25 mg once daily. There was no improvement in psoriasis over the following week, and he reported mild upper abdominal discomfort. He did not have any chest pain or dyspnea, and his pulse and blood pressure were normal. Serum electrolytes, liver function, lipid profile, and an ultrasound of the abdomen revealed no abnormalities. A repeat ECG showed no changes, and cardiac biomarkers were not elevated. Two days later, the patient collapsed while still in the hospital. A cardiac monitor and ECG showed ventricular tachycardia (VT)(Figure 2B); however, serum electrolytes, calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus levels were within reference range. Aggressive resuscitative measures including multiple attempts at cardioversion with up to 200 J (biphasic) and intravenous amiodarone infusion failed to revive the patient, and he died.

Proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor α are increased in young people with ventricular arrhythmias who have no evidence of myocardial injury (MI), suggesting an inflammatory background is involved.1 Psoriasis, a common immune-mediated inflammatory disease, has a chronic state of systemic inflammation with notably higher serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, and IL-18 compared to controls.2 This inflammation is not confined to skin but can involve blood vessels, joints, and the liver, as demonstrated by increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake.3 It also seems to exert its influence on supraventricular beat development in patients with psoriasis who do not have a history of CVEs.4 Tumor necrosis factor α is one of the major cytokines playing a role in the inflammatory process of psoriasis. Studies have shown serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α to correlate with the clinical symptoms of heart failure and to supraventricular arrhythmia in animal models.4 Various extreme CVEs can be an expression of this ongoing dynamic process. It would be interesting to know which specific factors among these inflammatory cytokines lead to rhythm irregularities.

Another theory is that young patients may experience micro-MI during the disease course. These small infarcted areas may act as aberrant pulse generators or lead to conduction disturbances. One study found increased correct QT interval dispersion, a predictor of ventricular arrhythmias, to be associated with psoriasis.5 A nationwide population-based matched cohort study by Chiu et al6 revealed that patients with psoriasis have a higher risk for arrhythmia independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Our patient also had severe unstable psoriasis for 8 years that may have led to increased accumulation of proarrhythmogenic cytokines in the heart and could have led to VT.

Acitretin as a potential cause of sudden cardiac death remains a possibility in our case; however, the exact mechanism leading to such sudden arrhythmia is lacking. Acitretin is known to increase serum triglycerides and cholesterol, specifically by shifting high-density lipoproteins to low-density lipoproteins, thereby increasing the risk for CVE. However, it takes time for such derangement to occur, eventually leading to CVE. Mittal et al7 reported a psoriasis patient who died secondary to MI after 5 days of low-dose acitretin. Lack of evidence makes acitretin a less likely cause of mortality.

We present a case of sudden cardiac death secondary to VT in a young patient with psoriasis and no other traditional cardiovascular risk factors. This case highlights the importance of being vigilant for adverse CVEs such as arrhythmia in psoriatic patients, especially in younger patients with severe unstable disease.

- Kowalewski M, Urban M, Mroczko B, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-alpha) and cardiac troponin I (cTnI) in serum of young people with ventricular arrhythmias. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2002;108:647-651.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005:273-279.

- Mehta NN, Yu Y, Saboury B, et al. Systemic and vascular inflammation in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis as measured by [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT): a pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1031-1039.

- Markuszeski L, Bissinger A, Janusz I, et al. Heart rate and arrhythmia in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Arch Med Res. 2007;38:64-69.

- Simsek H, Sahin M, Akyol A, et al. Increased risk of atrial and ventricular arrhythmia in long-lasting psoriasis patients. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:901215.

- Chiu HY, Chang WL, Huang WF, et al. Increased risk of arrhythmia in patients with psoriatic disease: a nationwide population-based matched cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:429-438.

- Mittal R, Malhotra S, Pandhi P, et al. Efficacy and safety of combination acitretin and pioglitazone therapy in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque-type psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:387-393.

To the Editor:

The evolution in the understanding of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis has unfolded many new facets of this immune-mediated inflammatory disease. Once considered to be just a cutaneous disease, psoriasis is not actually confined to skin but can involve almost any other system of the body. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality are the major concerns in patients with psoriasis. We report the sudden death of a young man with severe psoriasis.

A 31-year-old man was admitted for severe psoriasis with pustular exacerbation (Figures 1A and 1B). He had moderate to severe unstable disease during the last 8 years and was managed with oral methotrexate (0.3–0.5 mg/kg/wk). He was not compliant with treatment, which led to multiple relapses. There was no personal or family history of risk factors for cardiovascular events (CVEs). At the time of present hospitalization, his vital parameters were normal. Physical examination revealed erythematous scaly plaques on more than 75% of the body surface area. Multiple pustules also were noted, often coalescing to form plaques (Figure 1C). Baseline investigations consisting of complete blood cell count, lipid profile, liver and renal functions, and chest radiography were within reference range. Baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) at admission was unremarkable (Figure 2A), except for sinus tachycardia. Low-voltage complexes in limb leads were appreciated as well as a corrected QT interval of 420 milliseconds (within reference range). Echocardiography was normal (visual ejection fraction of 60%).

The patient was unable to tolerate methotrexate due to excessive nausea; he was started on oral acitretin 25 mg once daily. There was no improvement in psoriasis over the following week, and he reported mild upper abdominal discomfort. He did not have any chest pain or dyspnea, and his pulse and blood pressure were normal. Serum electrolytes, liver function, lipid profile, and an ultrasound of the abdomen revealed no abnormalities. A repeat ECG showed no changes, and cardiac biomarkers were not elevated. Two days later, the patient collapsed while still in the hospital. A cardiac monitor and ECG showed ventricular tachycardia (VT)(Figure 2B); however, serum electrolytes, calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus levels were within reference range. Aggressive resuscitative measures including multiple attempts at cardioversion with up to 200 J (biphasic) and intravenous amiodarone infusion failed to revive the patient, and he died.

Proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor α are increased in young people with ventricular arrhythmias who have no evidence of myocardial injury (MI), suggesting an inflammatory background is involved.1 Psoriasis, a common immune-mediated inflammatory disease, has a chronic state of systemic inflammation with notably higher serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, and IL-18 compared to controls.2 This inflammation is not confined to skin but can involve blood vessels, joints, and the liver, as demonstrated by increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake.3 It also seems to exert its influence on supraventricular beat development in patients with psoriasis who do not have a history of CVEs.4 Tumor necrosis factor α is one of the major cytokines playing a role in the inflammatory process of psoriasis. Studies have shown serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α to correlate with the clinical symptoms of heart failure and to supraventricular arrhythmia in animal models.4 Various extreme CVEs can be an expression of this ongoing dynamic process. It would be interesting to know which specific factors among these inflammatory cytokines lead to rhythm irregularities.

Another theory is that young patients may experience micro-MI during the disease course. These small infarcted areas may act as aberrant pulse generators or lead to conduction disturbances. One study found increased correct QT interval dispersion, a predictor of ventricular arrhythmias, to be associated with psoriasis.5 A nationwide population-based matched cohort study by Chiu et al6 revealed that patients with psoriasis have a higher risk for arrhythmia independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Our patient also had severe unstable psoriasis for 8 years that may have led to increased accumulation of proarrhythmogenic cytokines in the heart and could have led to VT.

Acitretin as a potential cause of sudden cardiac death remains a possibility in our case; however, the exact mechanism leading to such sudden arrhythmia is lacking. Acitretin is known to increase serum triglycerides and cholesterol, specifically by shifting high-density lipoproteins to low-density lipoproteins, thereby increasing the risk for CVE. However, it takes time for such derangement to occur, eventually leading to CVE. Mittal et al7 reported a psoriasis patient who died secondary to MI after 5 days of low-dose acitretin. Lack of evidence makes acitretin a less likely cause of mortality.

We present a case of sudden cardiac death secondary to VT in a young patient with psoriasis and no other traditional cardiovascular risk factors. This case highlights the importance of being vigilant for adverse CVEs such as arrhythmia in psoriatic patients, especially in younger patients with severe unstable disease.

To the Editor:

The evolution in the understanding of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis has unfolded many new facets of this immune-mediated inflammatory disease. Once considered to be just a cutaneous disease, psoriasis is not actually confined to skin but can involve almost any other system of the body. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality are the major concerns in patients with psoriasis. We report the sudden death of a young man with severe psoriasis.

A 31-year-old man was admitted for severe psoriasis with pustular exacerbation (Figures 1A and 1B). He had moderate to severe unstable disease during the last 8 years and was managed with oral methotrexate (0.3–0.5 mg/kg/wk). He was not compliant with treatment, which led to multiple relapses. There was no personal or family history of risk factors for cardiovascular events (CVEs). At the time of present hospitalization, his vital parameters were normal. Physical examination revealed erythematous scaly plaques on more than 75% of the body surface area. Multiple pustules also were noted, often coalescing to form plaques (Figure 1C). Baseline investigations consisting of complete blood cell count, lipid profile, liver and renal functions, and chest radiography were within reference range. Baseline electrocardiogram (ECG) at admission was unremarkable (Figure 2A), except for sinus tachycardia. Low-voltage complexes in limb leads were appreciated as well as a corrected QT interval of 420 milliseconds (within reference range). Echocardiography was normal (visual ejection fraction of 60%).

The patient was unable to tolerate methotrexate due to excessive nausea; he was started on oral acitretin 25 mg once daily. There was no improvement in psoriasis over the following week, and he reported mild upper abdominal discomfort. He did not have any chest pain or dyspnea, and his pulse and blood pressure were normal. Serum electrolytes, liver function, lipid profile, and an ultrasound of the abdomen revealed no abnormalities. A repeat ECG showed no changes, and cardiac biomarkers were not elevated. Two days later, the patient collapsed while still in the hospital. A cardiac monitor and ECG showed ventricular tachycardia (VT)(Figure 2B); however, serum electrolytes, calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus levels were within reference range. Aggressive resuscitative measures including multiple attempts at cardioversion with up to 200 J (biphasic) and intravenous amiodarone infusion failed to revive the patient, and he died.

Proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor α are increased in young people with ventricular arrhythmias who have no evidence of myocardial injury (MI), suggesting an inflammatory background is involved.1 Psoriasis, a common immune-mediated inflammatory disease, has a chronic state of systemic inflammation with notably higher serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, and IL-18 compared to controls.2 This inflammation is not confined to skin but can involve blood vessels, joints, and the liver, as demonstrated by increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake.3 It also seems to exert its influence on supraventricular beat development in patients with psoriasis who do not have a history of CVEs.4 Tumor necrosis factor α is one of the major cytokines playing a role in the inflammatory process of psoriasis. Studies have shown serum levels of tumor necrosis factor α to correlate with the clinical symptoms of heart failure and to supraventricular arrhythmia in animal models.4 Various extreme CVEs can be an expression of this ongoing dynamic process. It would be interesting to know which specific factors among these inflammatory cytokines lead to rhythm irregularities.

Another theory is that young patients may experience micro-MI during the disease course. These small infarcted areas may act as aberrant pulse generators or lead to conduction disturbances. One study found increased correct QT interval dispersion, a predictor of ventricular arrhythmias, to be associated with psoriasis.5 A nationwide population-based matched cohort study by Chiu et al6 revealed that patients with psoriasis have a higher risk for arrhythmia independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Our patient also had severe unstable psoriasis for 8 years that may have led to increased accumulation of proarrhythmogenic cytokines in the heart and could have led to VT.

Acitretin as a potential cause of sudden cardiac death remains a possibility in our case; however, the exact mechanism leading to such sudden arrhythmia is lacking. Acitretin is known to increase serum triglycerides and cholesterol, specifically by shifting high-density lipoproteins to low-density lipoproteins, thereby increasing the risk for CVE. However, it takes time for such derangement to occur, eventually leading to CVE. Mittal et al7 reported a psoriasis patient who died secondary to MI after 5 days of low-dose acitretin. Lack of evidence makes acitretin a less likely cause of mortality.

We present a case of sudden cardiac death secondary to VT in a young patient with psoriasis and no other traditional cardiovascular risk factors. This case highlights the importance of being vigilant for adverse CVEs such as arrhythmia in psoriatic patients, especially in younger patients with severe unstable disease.

- Kowalewski M, Urban M, Mroczko B, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-alpha) and cardiac troponin I (cTnI) in serum of young people with ventricular arrhythmias. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2002;108:647-651.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005:273-279.

- Mehta NN, Yu Y, Saboury B, et al. Systemic and vascular inflammation in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis as measured by [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT): a pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1031-1039.

- Markuszeski L, Bissinger A, Janusz I, et al. Heart rate and arrhythmia in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Arch Med Res. 2007;38:64-69.

- Simsek H, Sahin M, Akyol A, et al. Increased risk of atrial and ventricular arrhythmia in long-lasting psoriasis patients. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:901215.

- Chiu HY, Chang WL, Huang WF, et al. Increased risk of arrhythmia in patients with psoriatic disease: a nationwide population-based matched cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:429-438.

- Mittal R, Malhotra S, Pandhi P, et al. Efficacy and safety of combination acitretin and pioglitazone therapy in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque-type psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:387-393.

- Kowalewski M, Urban M, Mroczko B, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-alpha) and cardiac troponin I (cTnI) in serum of young people with ventricular arrhythmias. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2002;108:647-651.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005:273-279.

- Mehta NN, Yu Y, Saboury B, et al. Systemic and vascular inflammation in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis as measured by [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT): a pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1031-1039.

- Markuszeski L, Bissinger A, Janusz I, et al. Heart rate and arrhythmia in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Arch Med Res. 2007;38:64-69.

- Simsek H, Sahin M, Akyol A, et al. Increased risk of atrial and ventricular arrhythmia in long-lasting psoriasis patients. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:901215.

- Chiu HY, Chang WL, Huang WF, et al. Increased risk of arrhythmia in patients with psoriatic disease: a nationwide population-based matched cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:429-438.

- Mittal R, Malhotra S, Pandhi P, et al. Efficacy and safety of combination acitretin and pioglitazone therapy in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque-type psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:387-393.

Practice Points

- Low-grade chronic inflammation in patients with psoriasis can lead to vascular inflammation, which can further lead to the development of major adverse cardiovascular events (CVEs) and arrhythmia.

- The need for a multidisciplinary approach and close monitoring of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psoriasis to prevent a CVE is vital.

- Baseline electrocardiogram and biomarkers for cardiovascular disease also should be performed in young patients with severe or unstable psoriasis.

Psychiatric Morbidity in Patients With Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a common immune-mediated papulosquamous skin disease with a generally chronic course. Impairments in quality of life (QOL) and psychological morbidity in the form of anxiety and depression have been reported.1 Because psoriasis is not known to directly affect the central nervous system, the associated psychiatric morbidity is likely caused by the complex interplay of the stress, physical discomfort, and possible disfigurement inherent to psoriasis, as well as the emotional response to the condition mediated by the patient’s personality, emotional and cognitive state, and other social factors (eg, self-stigma and perceived stigma, lack of knowledge about the illness in the patient and in the community and family, lack of resources and support).2 Because a variety of methodologies have been used in research on the association of psoriasis with psychiatric morbidity, it is not easy to compare findings. Most studies have assessed psychiatric symptoms rather than findings from psychiatric diagnostic instruments.3 The diagnosis of psychiatric disorders in patients with psoriasis rather than focusing on symptoms alone is likely to be more useful in generating scientific epidemiologic data and also would serve as a guide in making treatment and policy decisions. Validated clinician-rated instruments are useful in generating these data. However, psychiatric diagnoses are often missed by dermatologists, which may have an adverse impact on eventual outcomes in psoriasis patients.4,5 Patient-assessed diagnostic instruments may help dermatologists overcome this problem.

This study investigated the prevalence and determinants of psychiatric disorders in a cohort of psoriasis patients in North India using both patient self-assessment and clinician-administered instruments.

Methods

Study Participants

The study was conducted from January 2013 to November 2013 at the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, a tertiary-level teaching hospital in Chandigarh, India, which serves the population of a large geographic area in North India. Clearance for this study was obtained from the institute ethics committee.

Patients with chronic plaque psoriasis who presented consecutively to the outpatient clinic of the Departments of Dermatology, Venereology, and Leprology during the study period were approached for participation. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Inclusion criteria were the ability to read the self-assessment questionnaires, and no financial compensation was offered for inclusion in the study. Patients with psoriatic arthritis as well as erythrodermic and pustular variants of psoriasis were excluded. Exclusion criteria also included patients with known diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory ailments, or other notable systemic comorbidities; however, patients did not undergo biochemical testing.

Assessments

A 2-stage methodology was employed. In the first stage of the assessment, sociodemographic and clinical data were recorded. Thereafter, psychiatric symptoms and morbidity were assessed using the patient health questionnaire (PHQ).6 Quality of life was assessed using the dermatology life quality index (DLQI).7 Both tools were based on patient self-assessment. Study participants could seek assistance from the clinician in completing the questionnaires, if needed. Psoriasis severity was evaluated by the clinician using the psoriasis area severity index (PASI) score.8

In the second stage of the assessment, participants underwent subsequent evaluation by a psychiatrist who was blinded to the results of the first assessments. All participants were screened using the Mini international neuropsychiatric interview (MINI)9 and a formal psychiatric diagnosis was made. In subsequent analyses, we considered psychiatric diagnoses as generated with MINI as the gold standard against which other results were compared.

A participant was considered positive for psychiatric morbidity if he/she was positive for at least 1 PHQ or MINI diagnosis.

To assess for concordance between the 2 diagnostic instruments, the following diagnostic groups were compared against each other: (1) MINI depressive disorders (DDs)(ie, major depressive episode, current and recurrent; dysthymia) versus PHQ depressive disorders (ie, major DDs and other DDs); (2) MINI anxiety disorders (ie, panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder) versus PHQ anxiety disorders (ie, panic syndrome and other anxiety syndromes); (3) MINI alcohol abuse (ie, alcohol dependence and abuse) versus PHQ alcohol abuse; (4) comorbid disorders if more than 1 diagnosis was made; and (5) any positive score on the MINI suicide module with a response other than not at all on PHQ depression module item 2(i), which deals with thoughts of self-harm and wishing that one was dead. The MINI depressive disorders and PHQ depressive disorders indicate the presence of a clinically significant depressive state and a need for assessment and treatment.

The PHQ can be used to diagnose somatoform disorders, while the MINI cannot be used. Because the somatoform disorders diagnosed were few in number and comorbid with DDs (n=3) and anxiety disorders (n=1), we included these cases with DDs and anxiety disorders, respectively, for purposes of statistical analysis. All data were analyzed using SPSS software.

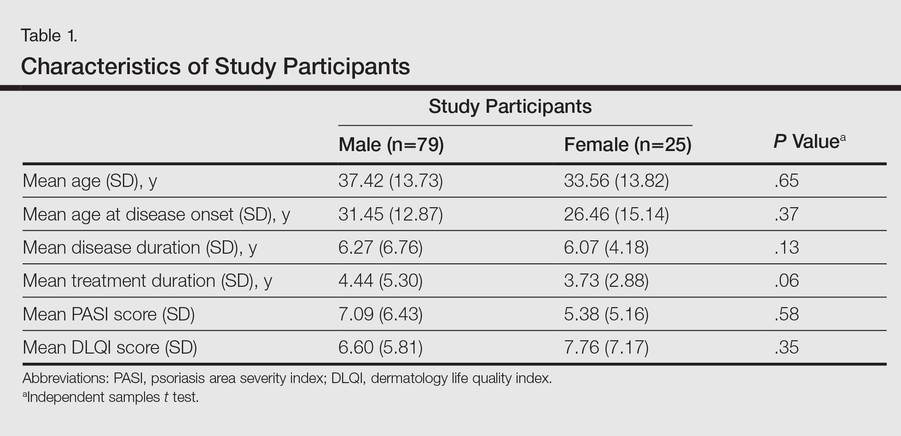

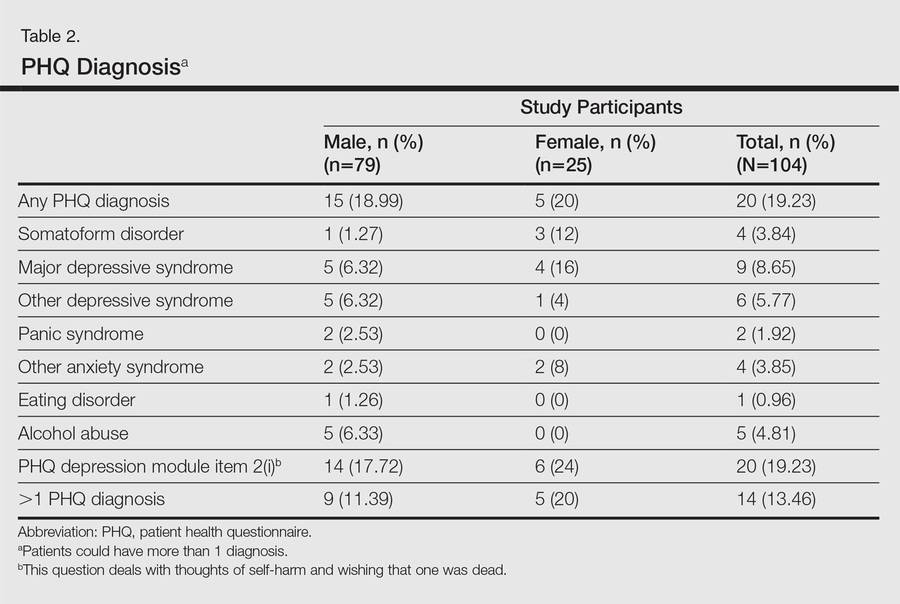

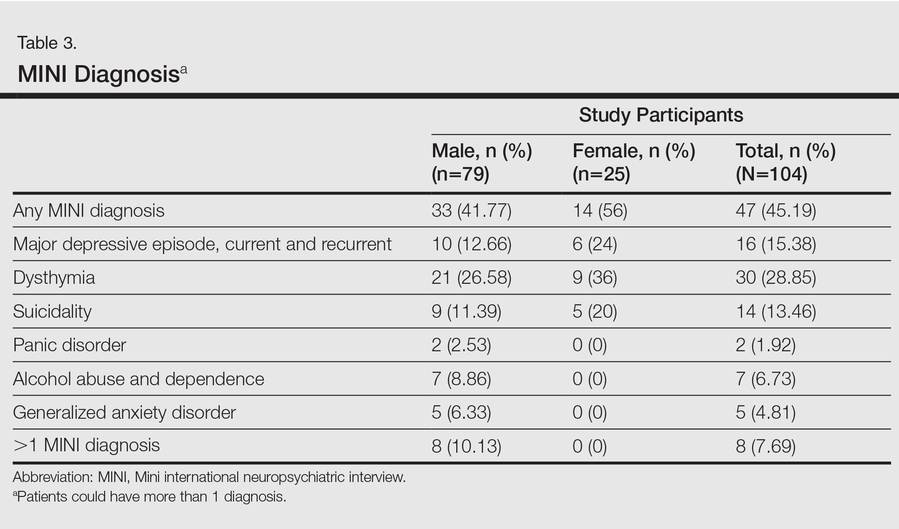

Results

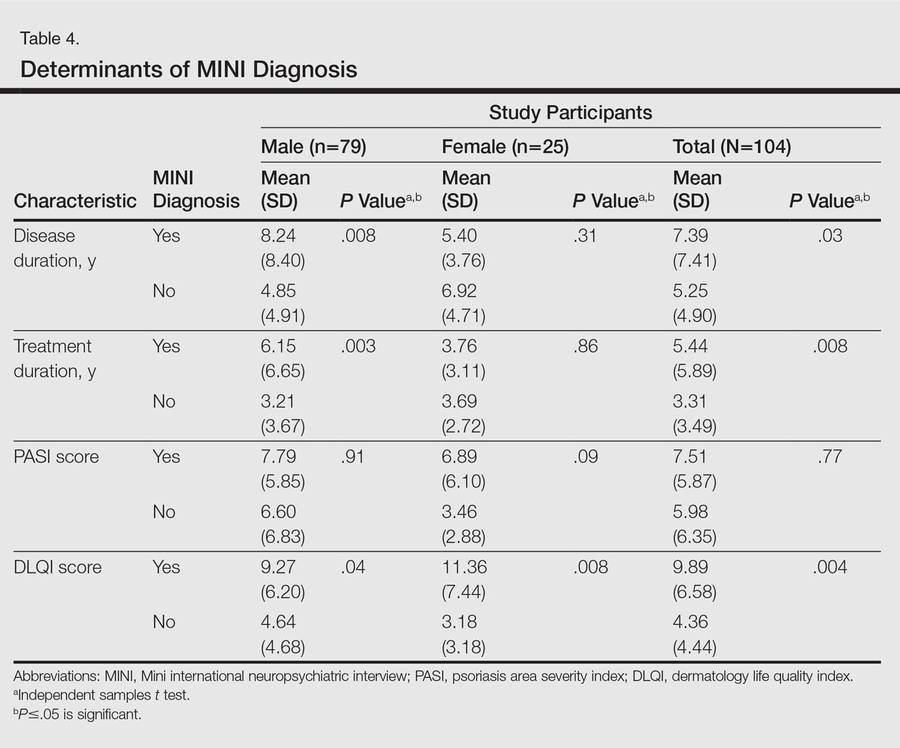

One hundred four participants were included in this study. The sociodemographic, clinical, and diagnostic profiles, as well as the determinants of MINI diagnosis, are provided in Tables 1 through 4. The PASI and DLQI scores indicated that most participants had mild to moderate psoriasis severity.10 The prevalence of alcohol-related disorders was only found in the male subpopulation, which is consistent with the sociocultural context of North India. Psoriasis severity (ie, PASI score) was not found to be a determinant of psychiatric diagnoses in the study population. There was no statistical difference in measures of current clinical status and treatment modality when those with or without any psychiatric diagnoses were compared. When the variables of disease duration, treatment duration, and DLQI were entered into a binary logistic regression with positive status for a MINI diagnosis as a dependent variable indicating the presence of a psychiatric disorder, it was found that the DLQI score was a significant predictor (b=0.19; SE=0.47; χ2=17.92; P<.05). This finding was the same for regression analyses for males and females separately and also for DD as a dependent variable.

Mean DLQI and PASI scores were positively correlated with each other (Pearson r=0.23; P=.01). This relationship was maintained in males (Pearson r=0.24; P=.03) but not in females (Pearson r=0.14; P=.30). The correlations between DLQI and PASI scores and both disease duration and treatment duration were not significant. The Cohen κ values for the interrater reliability analyses done to assess the concordance of the PHQ and MINI diagnostic groups were modest (0.31-0.42), which was true even when MINI depressive disorders without dysthymia and PHQ depressive disorders were compared.

Comment

Studies investigating psychiatric morbidity in psoriasis have varying methodologies, mostly assessing psychiatric symptoms rather than screening for psychiatric disorders.3 In chronic diseases such as psoriasis, there often is an overlap between disease symptoms and common psychiatric disorders (eg, depression).11 Therefore, assessment of symptoms can be misleading. The current study was designed to detect psychiatric disorders in psoriasis patients using both patient self-assessment and clinician-administered instruments. We also investigated the contribution of sociodemographic and clinical variables (eg, psoriasis severity, impairment in QOL) on psychiatric morbidity.

An increased risk for depression, anxiety, and suicidality associated with greater psoriasis severity has been reported.12 The results of the current study indicate that even in a patient population with predominantly mild to moderate psoriasis, psychiatric morbidity, particularly DDs, is common. This finding was seen both on patient self-assessment and clinician-administered evaluations. Earlier studies from this institution and region have reported a lower prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with psoriasis (24.7%–36.7%).13-16 However, prior studies were based on assessment of specific symptoms and clinical diagnoses derived from history and mental status examination rather than the administration of more rigorous research diagnostic assessment tools. A systematic review and meta-analysis also revealed a lower prevalence of clinical depression using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition) codes.3 A possible reason for this apparent discrepancy is the fact that psychiatric morbidity in a majority of participants in the current study was constituted by the diagnosis of dysthymia. If the diagnosis of dysthymia is removed from the current analysis, the prevalence of clinical major depressive syndromes is similar to other data. We found that chronic low-grade depression (dysthymia) was the most common diagnosis from the MINI. Lower prevalence was noted in a prior study, but methodology using clinical interviewing may have resulted in an underestimated prevalence.13 It also is possible that chronic low-grade depression in psoriasis patients may be missed or underestimated in comparison to more readily diagnosed and severe depressive syndromes in other studies. However, there is enough evidence to suggest that dysthymia is clinically relevant in the causation of morbidity and disability (eg, physical, psychological, or cognitive impairment) in patients with chronic physical disorders.17 This distinction between clinical major depressive syndrome and dysthymia is important because different treatment methods may be required; the former may warrant treatment with antidepressants in addition to psychosocial treatment modalities (eg, learning to cope with stress, problem-solving techniques), while the latter may benefit predominantly from psychosocial treatment modalities alone.18,19 In the current study, most of the participants who were diagnosed with dysthymia refused treatment with any psychotropic medications but perceived benefit from discussing their problems with a professional. Our results indicated that chronic low-grade depression is more common than more severe major depressive states, and mental health professionals who are well versed in psychosocial treatment modalities should play an integral role in treatment planning for patients with psoriasis.

In the current study, there was only a modest correlation between the results of the patient self-assessment and clinician-administered evaluations, which indicated that psychiatric disorders may not be obvious to clinicians unless specifically investigated, even for some severely depressed and suicidal patients. Given the high prevalence of clinically relevant psychiatric morbidity among psoriasis patients, dermatology professionals should be more sensitive to the possible presence of psychiatric disorders in this patient population and should consider the use of formal screening or other diagnostic tools for detection of depression and anxiety in psoriasis patients.

The main determinant of psychiatric morbidity in our study population was impairment in QOL. Interestingly enough, psoriasis severity was not associated with psychiatric morbidity in our study. Depressive states in patients with chronic physical illnesses are well known and could be due to the chronic stress of illness or impaired QOL, or depression may be a direct effect of the illness and/or treatment on the central nervous system. Psoriasis is not known to have any direct effect on the central nervous system. Our findings suggest that QOL impairment plays an important role in psychiatric morbidity in patients with psoriasis. Even though the DLQI is designed to measure QOL over the preceding week, our findings suggest that impairment in QOL in psoriasis is a manifestation of a more long-term effect of interplay between many factors; the impairment in activities of daily living, disease-related physical discomfort and impaired self-esteem and self-perception, impairments in interpersonal relationships, and the stress of chronicity of illness seem to play an important role. Additionally, variables such as emotional dysfunction, magnitude and site of the area of involvement, nature and magnitude of comorbidities, and complications of illness and coping also may be relevant.20 Although these factors are common in other chronic disorders, psoriasis in particular may predisposepatients to depression due to its unpredictable and relapsing nature, lack of any curative therapy, and the stigmatizing prominent lesions that often are impossible to camouflage. In chronic diseases such as psoriasis, the amelioration of impairment of different aspects of QOL may be more important than mere symptom control.

Our study was limited in that the study population was predominantly male. Fewer females may have consented to participate in the study due to time constraints associated with domestic responsibilities, reluctance to discuss psychological distress, or inability to meet the inclusion criteria (eg, level of education required to read questionnaires). However, there was no significant difference between males and females for sociodemographic variables or diagnoses other than alcohol-related disorders. Our study also had a cross-sectional design and there was no control group, without which it is difficult to assess the true prevalence and determinants of these psychiatric morbidities. Moreover, the sample size was small and did not include enough participants with moderate to severe psoriasis (ie, PASI score ≥10) to be able to detect a correlation between psychiatric morbidities and psoriasis severity. Our findings underline the need for effective screening and integrated management of psychiatric disorders in patients with psoriasis.

- Griffiths CE, Barker JN. Pathogenesis and clinical features of psoriasis. Lancet. 2007;370:263-271.

- Fried RG, Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Depression and skin disease. Dermatol Clin. 2005;23:657-664.

- Dowlatshahi EA, Wakkee M, Arends LR, et al. The prevalence and odds of depressive symptoms and clinical depression in psoriasis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1542-1551.

- Richards HL, Fortune DG, Weidmann A, et al. Detection of psychological distress in patients with psoriasis: low consensus between dermatologist and patient. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:1227-1233.

- Scharloo M, Kaptein AA, Weinman J, et al. Patients’ illness perceptions and coping as predictors of functional status in psoriasis: a 1-year follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:899-907.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. primary care evaluation of mental disorders. patient health questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737-1744.

- Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210-216.

- Langley RG, Ellis CN. Evaluating psoriasis with Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, Psoriasis Global Assessment, and Lattice System Physician’s Global Assessment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:563-569.

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(suppl 20):22-33, quiz 34-57.

- Mrowietz U, Kragballe K, Reich K, et al. Definition of treatment goals for moderate to severe psoriasis: a European consensus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2011;303:1-10.

- Ellis GK, Robinson JA, Crawford GB. When symptoms of disease overlap with symptoms of depression. Aust Fam Physician. 2006;35:647-649.

- Kurd SK, Troxel AB, Crits-Christoph P, et al. The risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidality in patients with psoriasis: a population-based cohort study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:891-895.

- Kumar V, Mattoo SK, Handa S. Psychiatric morbidity in pemphigus and psoriasis: a comparative study from India. Asian J Psychiatry. 2013;6:151-156.

- Mattoo S, Handa S, Kaur I, et al. Psychiatric morbidity in psoriasis: prevalence and correlates in India. Ger J Psychiatry. 2005;8:17-22.

- Mattoo SK, Handa S, Kaur I, et al. Psychiatric morbidity in vitiligo and psoriasis: a comparative study from India. J Dermatol. 2001;28:424-432.

- Mehta V, Malhotra S. Psychiatric evaluation of patients with psoriasis vulgaris and chronic urticaria. Ger J Psychiatry. 2007;10:104-110.

- Meeks TW, Vahia IV, Lavretsky H, et al. A tune in “a minor” can “b major”: a review of epidemiology, illness course, and public health implications of subthreshold depression in older adults. J Affect Disord. 2011;129:126-142.

- Hegerl U, Schönknecht P, Mergl R. Are antidepressants useful in the treatment of minor depression: a critical update of the current literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25:1-6.

- Rizzo M, Creed F, Goldberg D, et al. A systematic review of non-pharmacological treatments for depression in people with chronic physical health problems. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71:18-27.

- de Korte J, Sprangers MA, Mombers FM, et al. Quality of life in patients with psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:140-147.

Psoriasis is a common immune-mediated papulosquamous skin disease with a generally chronic course. Impairments in quality of life (QOL) and psychological morbidity in the form of anxiety and depression have been reported.1 Because psoriasis is not known to directly affect the central nervous system, the associated psychiatric morbidity is likely caused by the complex interplay of the stress, physical discomfort, and possible disfigurement inherent to psoriasis, as well as the emotional response to the condition mediated by the patient’s personality, emotional and cognitive state, and other social factors (eg, self-stigma and perceived stigma, lack of knowledge about the illness in the patient and in the community and family, lack of resources and support).2 Because a variety of methodologies have been used in research on the association of psoriasis with psychiatric morbidity, it is not easy to compare findings. Most studies have assessed psychiatric symptoms rather than findings from psychiatric diagnostic instruments.3 The diagnosis of psychiatric disorders in patients with psoriasis rather than focusing on symptoms alone is likely to be more useful in generating scientific epidemiologic data and also would serve as a guide in making treatment and policy decisions. Validated clinician-rated instruments are useful in generating these data. However, psychiatric diagnoses are often missed by dermatologists, which may have an adverse impact on eventual outcomes in psoriasis patients.4,5 Patient-assessed diagnostic instruments may help dermatologists overcome this problem.

This study investigated the prevalence and determinants of psychiatric disorders in a cohort of psoriasis patients in North India using both patient self-assessment and clinician-administered instruments.

Methods

Study Participants

The study was conducted from January 2013 to November 2013 at the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, a tertiary-level teaching hospital in Chandigarh, India, which serves the population of a large geographic area in North India. Clearance for this study was obtained from the institute ethics committee.

Patients with chronic plaque psoriasis who presented consecutively to the outpatient clinic of the Departments of Dermatology, Venereology, and Leprology during the study period were approached for participation. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Inclusion criteria were the ability to read the self-assessment questionnaires, and no financial compensation was offered for inclusion in the study. Patients with psoriatic arthritis as well as erythrodermic and pustular variants of psoriasis were excluded. Exclusion criteria also included patients with known diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory ailments, or other notable systemic comorbidities; however, patients did not undergo biochemical testing.

Assessments

A 2-stage methodology was employed. In the first stage of the assessment, sociodemographic and clinical data were recorded. Thereafter, psychiatric symptoms and morbidity were assessed using the patient health questionnaire (PHQ).6 Quality of life was assessed using the dermatology life quality index (DLQI).7 Both tools were based on patient self-assessment. Study participants could seek assistance from the clinician in completing the questionnaires, if needed. Psoriasis severity was evaluated by the clinician using the psoriasis area severity index (PASI) score.8

In the second stage of the assessment, participants underwent subsequent evaluation by a psychiatrist who was blinded to the results of the first assessments. All participants were screened using the Mini international neuropsychiatric interview (MINI)9 and a formal psychiatric diagnosis was made. In subsequent analyses, we considered psychiatric diagnoses as generated with MINI as the gold standard against which other results were compared.

A participant was considered positive for psychiatric morbidity if he/she was positive for at least 1 PHQ or MINI diagnosis.

To assess for concordance between the 2 diagnostic instruments, the following diagnostic groups were compared against each other: (1) MINI depressive disorders (DDs)(ie, major depressive episode, current and recurrent; dysthymia) versus PHQ depressive disorders (ie, major DDs and other DDs); (2) MINI anxiety disorders (ie, panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder) versus PHQ anxiety disorders (ie, panic syndrome and other anxiety syndromes); (3) MINI alcohol abuse (ie, alcohol dependence and abuse) versus PHQ alcohol abuse; (4) comorbid disorders if more than 1 diagnosis was made; and (5) any positive score on the MINI suicide module with a response other than not at all on PHQ depression module item 2(i), which deals with thoughts of self-harm and wishing that one was dead. The MINI depressive disorders and PHQ depressive disorders indicate the presence of a clinically significant depressive state and a need for assessment and treatment.

The PHQ can be used to diagnose somatoform disorders, while the MINI cannot be used. Because the somatoform disorders diagnosed were few in number and comorbid with DDs (n=3) and anxiety disorders (n=1), we included these cases with DDs and anxiety disorders, respectively, for purposes of statistical analysis. All data were analyzed using SPSS software.

Results

One hundred four participants were included in this study. The sociodemographic, clinical, and diagnostic profiles, as well as the determinants of MINI diagnosis, are provided in Tables 1 through 4. The PASI and DLQI scores indicated that most participants had mild to moderate psoriasis severity.10 The prevalence of alcohol-related disorders was only found in the male subpopulation, which is consistent with the sociocultural context of North India. Psoriasis severity (ie, PASI score) was not found to be a determinant of psychiatric diagnoses in the study population. There was no statistical difference in measures of current clinical status and treatment modality when those with or without any psychiatric diagnoses were compared. When the variables of disease duration, treatment duration, and DLQI were entered into a binary logistic regression with positive status for a MINI diagnosis as a dependent variable indicating the presence of a psychiatric disorder, it was found that the DLQI score was a significant predictor (b=0.19; SE=0.47; χ2=17.92; P<.05). This finding was the same for regression analyses for males and females separately and also for DD as a dependent variable.

Mean DLQI and PASI scores were positively correlated with each other (Pearson r=0.23; P=.01). This relationship was maintained in males (Pearson r=0.24; P=.03) but not in females (Pearson r=0.14; P=.30). The correlations between DLQI and PASI scores and both disease duration and treatment duration were not significant. The Cohen κ values for the interrater reliability analyses done to assess the concordance of the PHQ and MINI diagnostic groups were modest (0.31-0.42), which was true even when MINI depressive disorders without dysthymia and PHQ depressive disorders were compared.

Comment

Studies investigating psychiatric morbidity in psoriasis have varying methodologies, mostly assessing psychiatric symptoms rather than screening for psychiatric disorders.3 In chronic diseases such as psoriasis, there often is an overlap between disease symptoms and common psychiatric disorders (eg, depression).11 Therefore, assessment of symptoms can be misleading. The current study was designed to detect psychiatric disorders in psoriasis patients using both patient self-assessment and clinician-administered instruments. We also investigated the contribution of sociodemographic and clinical variables (eg, psoriasis severity, impairment in QOL) on psychiatric morbidity.

An increased risk for depression, anxiety, and suicidality associated with greater psoriasis severity has been reported.12 The results of the current study indicate that even in a patient population with predominantly mild to moderate psoriasis, psychiatric morbidity, particularly DDs, is common. This finding was seen both on patient self-assessment and clinician-administered evaluations. Earlier studies from this institution and region have reported a lower prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with psoriasis (24.7%–36.7%).13-16 However, prior studies were based on assessment of specific symptoms and clinical diagnoses derived from history and mental status examination rather than the administration of more rigorous research diagnostic assessment tools. A systematic review and meta-analysis also revealed a lower prevalence of clinical depression using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition) codes.3 A possible reason for this apparent discrepancy is the fact that psychiatric morbidity in a majority of participants in the current study was constituted by the diagnosis of dysthymia. If the diagnosis of dysthymia is removed from the current analysis, the prevalence of clinical major depressive syndromes is similar to other data. We found that chronic low-grade depression (dysthymia) was the most common diagnosis from the MINI. Lower prevalence was noted in a prior study, but methodology using clinical interviewing may have resulted in an underestimated prevalence.13 It also is possible that chronic low-grade depression in psoriasis patients may be missed or underestimated in comparison to more readily diagnosed and severe depressive syndromes in other studies. However, there is enough evidence to suggest that dysthymia is clinically relevant in the causation of morbidity and disability (eg, physical, psychological, or cognitive impairment) in patients with chronic physical disorders.17 This distinction between clinical major depressive syndrome and dysthymia is important because different treatment methods may be required; the former may warrant treatment with antidepressants in addition to psychosocial treatment modalities (eg, learning to cope with stress, problem-solving techniques), while the latter may benefit predominantly from psychosocial treatment modalities alone.18,19 In the current study, most of the participants who were diagnosed with dysthymia refused treatment with any psychotropic medications but perceived benefit from discussing their problems with a professional. Our results indicated that chronic low-grade depression is more common than more severe major depressive states, and mental health professionals who are well versed in psychosocial treatment modalities should play an integral role in treatment planning for patients with psoriasis.