User login

The Evaluation of Medical Inpatients Who Are Admitted on Long-term Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain

Hospitalists face complex questions about how to evaluate and treat the large number of individuals who are admitted on long-term opioid therapy (LTOT, defined as lasting 3 months or longer) for chronic noncancer pain. A recent study at one Veterans Affairs hospital, found 26% of medical inpatients were on LTOT.1 Over the last 2 decades, use of LTOT has risen substantially in the United States, including among middle-aged and older adults.2 Concurrently, inpatient hospitalizations related to the overuse of prescription opioids, including overdose, dependence, abuse, and adverse drug events, have increased by 153%.3 Individuals on LTOT can also be hospitalized for exacerbations of the opioid-treated chronic pain condition or unrelated conditions. In addition to affecting rates of hospitalization, use of LTOT is associated with higher rates of in-hospital adverse events, longer hospital stays, and higher readmission rates.1,4,5

Physicians find managing chronic pain to be stressful, are often concerned about misuse and addiction, and believe their training in opioid prescribing is inadequate.6 Hospitalists report confidence in assessing and prescribing opioids for acute pain but limited success and satisfaction with treating exacerbations of chronic pain.7 Although half of all hospitalized patients receive opioids,5 little information is available to guide the care of hospitalized medical patients on LTOT for chronic noncancer pain.8,9

Our multispecialty team sought to synthesize guideline recommendations and primary literature relevant to the assessment of medical inpatients on LTOT to assist practitioners balance effective pain treatment and opioid risk reduction. This article addresses obtaining a comprehensive pain history, identifying misuse and opioid use disorders, assessing the risk of overdose and adverse drug events, gauging the risk of withdrawal, and based on such findings, appraise indications for opioid therapy. Other authors have recently published narrative reviews on the management of acute pain in hospitalized patients with opioid dependence and the inpatient management of opioid use disorder.10,11

METHODS

To identify primary literature, we searched PubMed, EMBASE, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Health Economic Evaluations Database, key meeting abstracts, and hand searches. To identify guidelines, we searched PubMed, National Guidelines Clearinghouse, specialty societies’ websites, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the United Kingdom National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the Canadian Medical Association, and the Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council. Search terms related to opioids and chronic pain, which was last updated in October 2016.12

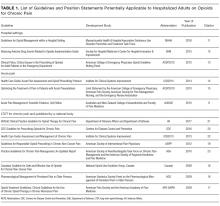

We selected English-language documents on opioids and chronic pain among adults, excluding pain in the setting of procedures, labor and delivery, life-limiting illness, or specific conditions. For primary literature, we considered intervention studies of any design that addressed pain management among hospitalized medical patients. We included guidelines and specialty society position statements published after January 1, 2009, that addressed pain in the hospital setting, acute pain in any setting, or chronic pain in the outpatient setting if published by a national body. Due to the paucity of documents specific to inpatient care, we used a narrative review format to synthesize information. Dual reviewers extracted guideline recommendations potentially relevant to medical inpatients on LTOT. We also summarize relevant assessment instruments, emphasizing very brief screening instruments, which may be more likely to be used by busy hospitalists.

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

Obtaining a Comprehensive Pain History

Hospitalists newly evaluating patients on LTOT often face a dual challenge: deciding if the patient has an immediate indication for additional opioids and if the current long-term opioid regimen should be altered or discontinued. In general, opioids are an accepted short-term treatment for moderate to severe acute pain but their role in chronic noncancer pain is controversial. Newly released guidelines by the CDC recommend initiating LTOT as a last resort, and the Departments of Veterans Affairs and Defense guidelines recommend against initiation of LTOT.22,23

A key first step, therefore, is distinguishing between acute and chronic pain. Among patients on LTOT, pain can represent a new acute pain condition, an exacerbation of chronic pain, opioid-induced hyperalgesia, or opioid withdrawal. Acute pain is defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in relation to such damage.26 In contrast, chronic pain is a complex response that may not be related to actual or ongoing tissue damage, and is influenced by physiological, contextual, and psychological factors. Two acute pain guidelines and 1 chronic pain guideline recommend distinguishing acute and chronic pain,9,16,21 3 chronic pain guidelines reinforce the importance of obtaining a pain history (including timing, intensity, frequency, onset, etc),20,22,23 and 6 guidelines recommend ascertaining a history of prior pain-related treatments.9,13,14,16,20,22 Inquiring how the current pain compares with symptoms “on a good day,” what activities the patient can usually perform, and what the patient does outside the hospital to cope with pain can serve as entry into this conversation.

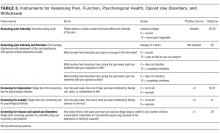

In addition to function, 5 guidelines, including 2 specific guidelines for acute pain or the hospital setting, recommend obtaining a detailed psychosocial history to identify life stressors and gain insight into the patient’s coping skills.14,16,19,20,22 Psychiatric symptoms can intensify the experience of pain or hamper coping ability. Anxiety, depression, and insomnia frequently coexist in patients with chronic pain.31 As such, 3 hospital setting/acute pain guidelines and 3 chronic pain guidelines recommend screening for mental health issues including anxiety and depression.13,14,16,20,22,23 Several depression screening instruments have been validated among inpatients,32 and there are validated single-item, self-administered instruments for both depression and anxiety (Table 3).32,33

Although obtaining a comprehensive history before making treatment decisions is ideal, some patients present in extremis. In emergency departments, some guidelines endorse prompt administration of analgesics based on patient self-report, prior to establishing a diagnosis.17 Given concerns about the growing prevalence of opioid use disorders, several states now recommend emergency medicine prescribers screen for misuse before giving opioids and avoid parenteral opioids for acute exacerbations of chronic pain.34 Treatments received in emergency departments set patients’ expectations for the care they receive during hospitalization, and hospitalists may find it necessary to explain therapies appropriate for urgent management are not intended to be sustained.

Identifying Misuse and Opioid Use Disorders

Nonmedical use of prescription opioids and opioid use disorders have more than doubled over the last decade.35 Five guidelines, including 3 specific guidelines for acute pain or the hospital setting, recommend screening for opioid misuse.13,14,16,19,23 Many states mandate practitioners assess patients for substance use disorders before prescribing controlled substances.36 Instruments to identify aberrant and risky use include the Current Opioid Misuse Measure,37 Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire,38 Addiction Behaviors Checklist,39 Screening Tool for Abuse,40 and the Self-Administered Single-Item Screening Question (Table 3).41 However, the evidence for these and other tools is limited and absent for the inpatient setting.21,42

In addition to obtaining a history from the patient, 4 guidelines specific to hospital settings/acute pain and 4 chronic pain guidelines recommend practitioners access prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs).13-16,19,21-24 PDMPs exist in all states except Missouri, and about half of states mandate practitioners check the PDMP database in certain circumstances.36 Studies examining the effects of PDMPs on prescribing are limited, but checking these databases can uncover concerning patterns including overlapping prescriptions or multiple prescribers.43 PDMPs can also confirm reported medication doses, for which patient report may be less reliable.

Two hospital/acute pain guidelines and 5 chronic pain guidelines also recommend urine drug testing, although differing on when and whom to test, with some favoring universal screening.11,20,23 Screening hospitalized patients may reveal substances not reported by patients, but medications administered in emergency departments can confound results. Furthermore, the commonly used immunoassay does not distinguish heroin from prescription opioids, nor detect hydrocodone, oxycodone, methadone, buprenorphine, or certain benzodiazepines. Chromatography/mass spectrometry assays can but are often not available from hospital laboratories. The differential for unexpected results includes substance use, self treatment of uncontrolled pain, diversion, or laboratory error.20

If concerning opioid use is identified, 3 hospital setting/acute pain specific guidelines and the CDC guideline recommend sharing concerns with patients and assessing for a substance use disorder.9,13,16,22 Determining whether patients have an opioid use disorder that meets the criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th Edition44 can be challenging. Patients may minimize or deny symptoms or fear that the stigma of an opioid use disorder will lead to dismissive or subpar care. Additionally, substance use disorders are subject to federal confidentiality regulations, which can hamper acquisition of information from providers.45 Thus, hospitalists may find specialty consultation helpful to confirm the diagnosis.

Assessing the Risk of Overdose and Adverse Drug Events

Oversedation, respiratory depression, and death can result from iatrogenic or self-administered opioid overdose in the hospital.5 Patient factors that increase this risk among outpatients include a prior history of overdose, preexisting substance use disorders, cognitive impairment, mood and personality disorders, chronic kidney disease, sleep apnea, obstructive lung disease, and recent abstinence from opioids.12 Medication factors include concomitant use of benzodiazepines and other central nervous system depressants, including alcohol; recent initiation of long-acting opioids; use of fentanyl patches, immediate-release fentanyl, or methadone; rapid titration; switching opioids without adequate dose reduction; pharmacokinetic drug–drug interactions; and, importantly, higher doses.12,22 Two guidelines specific to acute pain and hospital settings and 5 chronic pain guidelines recommend screening for use of benzodiazepines among patients on LTOT.13,14,16,18-20,22,21

The CDC guideline recommends careful assessment when doses exceed 50 mg of morphine equivalents per day and avoiding doses above 90 mg per day due to the heightened risk of overdose.22 In the hospital, 23% of patients receive doses at or above 100 mg of morphine equivalents per day,5 and concurrent use of central nervous system depressants is common. Changes in kidney and liver function during acute illness may impact opioid metabolism and contribute to overdose.

In addition to overdose, opioids are leading causes of adverse drug events during hospitalization.46 Most studies have focused on surgical patients reporting common opioid-related events as nausea/vomiting, pruritus, rash, mental status changes, respiratory depression, ileus, and urinary retention.47 Hospitalized patients may also exhibit chronic adverse effects due to LTOT. At least one-third of patients on LTOT eventually stop because of adverse effects, such as endocrinopathies, sleep disordered breathing, constipation, fractures, falls, and mental status changes.48 Patients may lack awareness that their symptoms are attributable to opioids and are willing to reduce their opioid use once informed, especially when alternatives are offered to alleviate pain.

Gauging the Risk of Withdrawal

Sudden discontinuation of LTOT by patients, practitioners, or intercurrent events can have unanticipated and undesirable consequences. Withdrawal is not only distressing for patients; it can be dangerous because patients may resort to illicit use, diversion of opioids, or masking opioid withdrawal with other substances such as alcohol. The anxiety and distress associated with withdrawal, or anticipatory fear about withdrawal, can undermine therapeutic alliance and interfere with processes of care. Reviewed guidelines did not offer recommendations regarding withdrawal risk or specific strategies for avoidance. There is no specific prior dose threshold or degree of reduction in opioids that puts patients at risk for withdrawal, in part due to patients’ beliefs, expectations, and differences in response to opioid formulations. Symptoms of opioid withdrawal have been compared to a severe case of influenza, including stomach cramps, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, tremor and muscle twitching, sweating, restlessness, yawning, tachycardia, anxiety and irritability, bone and joint aches, runny nose, tearing, and piloerection.49 The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS)49 and the Clinical Institute Narcotic Assessment51 are clinician-administered tools to assess opioid withdrawal similar to the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale, Revised,52 to monitor for withdrawal in the inpatient setting.

Synthesizing and Appraising the Indications for Opioid Therapy

For medical inpatients who report adequate pain control and functional outcomes on current doses of LTOT, without evidence of misuse, the pragmatic approach is to continue the treatment plan established by the outpatient clinician rather than escalating or tapering the dose. If opioids are prescribed at discharge, 3 hospital setting/acute pain guidelines and the CDC guideline recommend prescribing the lowest effective dose of immediate release opioids for 3 to 7 days.13,15,16,22

When patients exhibit evidence of an opioid use disorder, have a history of serious overdose, or are experiencing intolerable opioid-related adverse events, the hospitalist may conclude the harms of LTOT outweigh the benefits. For these patients, opioid treatment in the hospital can be aimed at preventing withdrawal, avoiding the perpetuation of inappropriate opioid use, managing other acute medical conditions, and communicating with outpatient prescribers. For patients with misuse, discontinuing opioids is potentially harmful and may be perceived as punitive. Hospitalists should consider consulting addiction or mental health specialists to assist with formulating a plan of care. However, such specialists may not be available in smaller or rural hospitals and referral at discharge can be challenging.53

Beginning to taper opioids during the hospitalization can be appropriate when patients are motivated and can transition to an outpatient provider who will supervise the taper. In ambulatory settings, tapers of 10% to 30% every 2 to 5 days are generally well tolerated.54 If patients started tapering opioids under supervision of an outpatient provider prior to hospitalization; ideally, the taper can be continued during hospitalization with close coordination with the outpatient clinician.

Unfortunately, many patients on LTOT are admitted with new sources of acute pain and or exacerbations of chronic pain, and some have concomitant substance use disorders; we plan to address the management of these complex situations in future work.

Despite the frequency with which patients on LTOT are hospitalized for nonsurgical stays and the challenges inherent in evaluating pain and assessing the possibility of substance use disorders, no formal guidelines or empirical research studies pertain to this population. Guidelines in this review were developed for hospital settings and acute pain in the absence of LTOT, and for outpatient care of patients on LTOT. We also included a nonsystematic synthesis of literature that varied in relevance to medical inpatients on LTOT.

CONCLUSIONS

Although inpatient assessment and treatment of patients with LTOT remains an underresearched area, we were able to extract and synthesize recommendations from 14 guideline statements and apply these to the assessment of patients with LTOT in the inpatient setting. Hospitalists frequently encounter patients on LTOT for chronic nonmalignant pain and are faced with complex decisions about the effectiveness and safety of LTOT; appropriate patient assessment is fundamental to making these decisions. Key guideline recommendations relevant to inpatient assessment include assessing both pain and functional status, differentiating acute from chronic pain, ascertaining preadmission pain treatment history, obtaining a psychosocial history, screening for mental health issues such as depression and anxiety, screening for substance use disorders, checking state prescription drug monitoring databases, ordering urine drug immunoassays, detecting use of sedative-hypnotics, identifying medical conditions associated with increased risk of overdose and adverse events, and appraising the potential benefits and harms of opioid therapy. Although approaches to assessing medical inpatients on LTOT can be extrapolated from outpatient guidelines, observational studies, and small studies in surgical populations, more work is needed to address these critical topics for inpatients on LTOT.

Disclosure

Dr. Herzig was funded by grant number K23AG042459 from the National Institute on Aging. The funding organization had no involvement in any aspect of the study, including design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. All other authors have no relevant conflicts of interest with the work.

1. Mosher HJ, Jiang L, Sarrazin MSV, Cram P, Kaboli PJ, Vander Weg MW. Prevalence and Characteristics of Hospitalized Adults on Chronic Opioid Therapy. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):82-87. PubMed

2. Campbell CI, Weisner C, Leresche L, et al. Age and Gender Trends in Long-Term Opioid Analgesic Use for Noncancer Pain. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2541-2547. PubMed

3. Owens PL, Barrett ML, Weiss AJ, Washington RE, Kronick R. Hospital Inpatient Utilization Related to Opioid Overuse among Adults, 1993–2012. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. PubMed

33. Young QR, Nguyen M, Roth S, Broadberry A, Mackay MH. Single-Item Measures for Depression and Anxiety: Validation of the Screening Tool for Psychological Distress in an Inpatient Cardiology Setting. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015;14(6):544-551. PubMed

Hospitalists face complex questions about how to evaluate and treat the large number of individuals who are admitted on long-term opioid therapy (LTOT, defined as lasting 3 months or longer) for chronic noncancer pain. A recent study at one Veterans Affairs hospital, found 26% of medical inpatients were on LTOT.1 Over the last 2 decades, use of LTOT has risen substantially in the United States, including among middle-aged and older adults.2 Concurrently, inpatient hospitalizations related to the overuse of prescription opioids, including overdose, dependence, abuse, and adverse drug events, have increased by 153%.3 Individuals on LTOT can also be hospitalized for exacerbations of the opioid-treated chronic pain condition or unrelated conditions. In addition to affecting rates of hospitalization, use of LTOT is associated with higher rates of in-hospital adverse events, longer hospital stays, and higher readmission rates.1,4,5

Physicians find managing chronic pain to be stressful, are often concerned about misuse and addiction, and believe their training in opioid prescribing is inadequate.6 Hospitalists report confidence in assessing and prescribing opioids for acute pain but limited success and satisfaction with treating exacerbations of chronic pain.7 Although half of all hospitalized patients receive opioids,5 little information is available to guide the care of hospitalized medical patients on LTOT for chronic noncancer pain.8,9

Our multispecialty team sought to synthesize guideline recommendations and primary literature relevant to the assessment of medical inpatients on LTOT to assist practitioners balance effective pain treatment and opioid risk reduction. This article addresses obtaining a comprehensive pain history, identifying misuse and opioid use disorders, assessing the risk of overdose and adverse drug events, gauging the risk of withdrawal, and based on such findings, appraise indications for opioid therapy. Other authors have recently published narrative reviews on the management of acute pain in hospitalized patients with opioid dependence and the inpatient management of opioid use disorder.10,11

METHODS

To identify primary literature, we searched PubMed, EMBASE, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Health Economic Evaluations Database, key meeting abstracts, and hand searches. To identify guidelines, we searched PubMed, National Guidelines Clearinghouse, specialty societies’ websites, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the United Kingdom National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the Canadian Medical Association, and the Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council. Search terms related to opioids and chronic pain, which was last updated in October 2016.12

We selected English-language documents on opioids and chronic pain among adults, excluding pain in the setting of procedures, labor and delivery, life-limiting illness, or specific conditions. For primary literature, we considered intervention studies of any design that addressed pain management among hospitalized medical patients. We included guidelines and specialty society position statements published after January 1, 2009, that addressed pain in the hospital setting, acute pain in any setting, or chronic pain in the outpatient setting if published by a national body. Due to the paucity of documents specific to inpatient care, we used a narrative review format to synthesize information. Dual reviewers extracted guideline recommendations potentially relevant to medical inpatients on LTOT. We also summarize relevant assessment instruments, emphasizing very brief screening instruments, which may be more likely to be used by busy hospitalists.

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

Obtaining a Comprehensive Pain History

Hospitalists newly evaluating patients on LTOT often face a dual challenge: deciding if the patient has an immediate indication for additional opioids and if the current long-term opioid regimen should be altered or discontinued. In general, opioids are an accepted short-term treatment for moderate to severe acute pain but their role in chronic noncancer pain is controversial. Newly released guidelines by the CDC recommend initiating LTOT as a last resort, and the Departments of Veterans Affairs and Defense guidelines recommend against initiation of LTOT.22,23

A key first step, therefore, is distinguishing between acute and chronic pain. Among patients on LTOT, pain can represent a new acute pain condition, an exacerbation of chronic pain, opioid-induced hyperalgesia, or opioid withdrawal. Acute pain is defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in relation to such damage.26 In contrast, chronic pain is a complex response that may not be related to actual or ongoing tissue damage, and is influenced by physiological, contextual, and psychological factors. Two acute pain guidelines and 1 chronic pain guideline recommend distinguishing acute and chronic pain,9,16,21 3 chronic pain guidelines reinforce the importance of obtaining a pain history (including timing, intensity, frequency, onset, etc),20,22,23 and 6 guidelines recommend ascertaining a history of prior pain-related treatments.9,13,14,16,20,22 Inquiring how the current pain compares with symptoms “on a good day,” what activities the patient can usually perform, and what the patient does outside the hospital to cope with pain can serve as entry into this conversation.

In addition to function, 5 guidelines, including 2 specific guidelines for acute pain or the hospital setting, recommend obtaining a detailed psychosocial history to identify life stressors and gain insight into the patient’s coping skills.14,16,19,20,22 Psychiatric symptoms can intensify the experience of pain or hamper coping ability. Anxiety, depression, and insomnia frequently coexist in patients with chronic pain.31 As such, 3 hospital setting/acute pain guidelines and 3 chronic pain guidelines recommend screening for mental health issues including anxiety and depression.13,14,16,20,22,23 Several depression screening instruments have been validated among inpatients,32 and there are validated single-item, self-administered instruments for both depression and anxiety (Table 3).32,33

Although obtaining a comprehensive history before making treatment decisions is ideal, some patients present in extremis. In emergency departments, some guidelines endorse prompt administration of analgesics based on patient self-report, prior to establishing a diagnosis.17 Given concerns about the growing prevalence of opioid use disorders, several states now recommend emergency medicine prescribers screen for misuse before giving opioids and avoid parenteral opioids for acute exacerbations of chronic pain.34 Treatments received in emergency departments set patients’ expectations for the care they receive during hospitalization, and hospitalists may find it necessary to explain therapies appropriate for urgent management are not intended to be sustained.

Identifying Misuse and Opioid Use Disorders

Nonmedical use of prescription opioids and opioid use disorders have more than doubled over the last decade.35 Five guidelines, including 3 specific guidelines for acute pain or the hospital setting, recommend screening for opioid misuse.13,14,16,19,23 Many states mandate practitioners assess patients for substance use disorders before prescribing controlled substances.36 Instruments to identify aberrant and risky use include the Current Opioid Misuse Measure,37 Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire,38 Addiction Behaviors Checklist,39 Screening Tool for Abuse,40 and the Self-Administered Single-Item Screening Question (Table 3).41 However, the evidence for these and other tools is limited and absent for the inpatient setting.21,42

In addition to obtaining a history from the patient, 4 guidelines specific to hospital settings/acute pain and 4 chronic pain guidelines recommend practitioners access prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs).13-16,19,21-24 PDMPs exist in all states except Missouri, and about half of states mandate practitioners check the PDMP database in certain circumstances.36 Studies examining the effects of PDMPs on prescribing are limited, but checking these databases can uncover concerning patterns including overlapping prescriptions or multiple prescribers.43 PDMPs can also confirm reported medication doses, for which patient report may be less reliable.

Two hospital/acute pain guidelines and 5 chronic pain guidelines also recommend urine drug testing, although differing on when and whom to test, with some favoring universal screening.11,20,23 Screening hospitalized patients may reveal substances not reported by patients, but medications administered in emergency departments can confound results. Furthermore, the commonly used immunoassay does not distinguish heroin from prescription opioids, nor detect hydrocodone, oxycodone, methadone, buprenorphine, or certain benzodiazepines. Chromatography/mass spectrometry assays can but are often not available from hospital laboratories. The differential for unexpected results includes substance use, self treatment of uncontrolled pain, diversion, or laboratory error.20

If concerning opioid use is identified, 3 hospital setting/acute pain specific guidelines and the CDC guideline recommend sharing concerns with patients and assessing for a substance use disorder.9,13,16,22 Determining whether patients have an opioid use disorder that meets the criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th Edition44 can be challenging. Patients may minimize or deny symptoms or fear that the stigma of an opioid use disorder will lead to dismissive or subpar care. Additionally, substance use disorders are subject to federal confidentiality regulations, which can hamper acquisition of information from providers.45 Thus, hospitalists may find specialty consultation helpful to confirm the diagnosis.

Assessing the Risk of Overdose and Adverse Drug Events

Oversedation, respiratory depression, and death can result from iatrogenic or self-administered opioid overdose in the hospital.5 Patient factors that increase this risk among outpatients include a prior history of overdose, preexisting substance use disorders, cognitive impairment, mood and personality disorders, chronic kidney disease, sleep apnea, obstructive lung disease, and recent abstinence from opioids.12 Medication factors include concomitant use of benzodiazepines and other central nervous system depressants, including alcohol; recent initiation of long-acting opioids; use of fentanyl patches, immediate-release fentanyl, or methadone; rapid titration; switching opioids without adequate dose reduction; pharmacokinetic drug–drug interactions; and, importantly, higher doses.12,22 Two guidelines specific to acute pain and hospital settings and 5 chronic pain guidelines recommend screening for use of benzodiazepines among patients on LTOT.13,14,16,18-20,22,21

The CDC guideline recommends careful assessment when doses exceed 50 mg of morphine equivalents per day and avoiding doses above 90 mg per day due to the heightened risk of overdose.22 In the hospital, 23% of patients receive doses at or above 100 mg of morphine equivalents per day,5 and concurrent use of central nervous system depressants is common. Changes in kidney and liver function during acute illness may impact opioid metabolism and contribute to overdose.

In addition to overdose, opioids are leading causes of adverse drug events during hospitalization.46 Most studies have focused on surgical patients reporting common opioid-related events as nausea/vomiting, pruritus, rash, mental status changes, respiratory depression, ileus, and urinary retention.47 Hospitalized patients may also exhibit chronic adverse effects due to LTOT. At least one-third of patients on LTOT eventually stop because of adverse effects, such as endocrinopathies, sleep disordered breathing, constipation, fractures, falls, and mental status changes.48 Patients may lack awareness that their symptoms are attributable to opioids and are willing to reduce their opioid use once informed, especially when alternatives are offered to alleviate pain.

Gauging the Risk of Withdrawal

Sudden discontinuation of LTOT by patients, practitioners, or intercurrent events can have unanticipated and undesirable consequences. Withdrawal is not only distressing for patients; it can be dangerous because patients may resort to illicit use, diversion of opioids, or masking opioid withdrawal with other substances such as alcohol. The anxiety and distress associated with withdrawal, or anticipatory fear about withdrawal, can undermine therapeutic alliance and interfere with processes of care. Reviewed guidelines did not offer recommendations regarding withdrawal risk or specific strategies for avoidance. There is no specific prior dose threshold or degree of reduction in opioids that puts patients at risk for withdrawal, in part due to patients’ beliefs, expectations, and differences in response to opioid formulations. Symptoms of opioid withdrawal have been compared to a severe case of influenza, including stomach cramps, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, tremor and muscle twitching, sweating, restlessness, yawning, tachycardia, anxiety and irritability, bone and joint aches, runny nose, tearing, and piloerection.49 The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS)49 and the Clinical Institute Narcotic Assessment51 are clinician-administered tools to assess opioid withdrawal similar to the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale, Revised,52 to monitor for withdrawal in the inpatient setting.

Synthesizing and Appraising the Indications for Opioid Therapy

For medical inpatients who report adequate pain control and functional outcomes on current doses of LTOT, without evidence of misuse, the pragmatic approach is to continue the treatment plan established by the outpatient clinician rather than escalating or tapering the dose. If opioids are prescribed at discharge, 3 hospital setting/acute pain guidelines and the CDC guideline recommend prescribing the lowest effective dose of immediate release opioids for 3 to 7 days.13,15,16,22

When patients exhibit evidence of an opioid use disorder, have a history of serious overdose, or are experiencing intolerable opioid-related adverse events, the hospitalist may conclude the harms of LTOT outweigh the benefits. For these patients, opioid treatment in the hospital can be aimed at preventing withdrawal, avoiding the perpetuation of inappropriate opioid use, managing other acute medical conditions, and communicating with outpatient prescribers. For patients with misuse, discontinuing opioids is potentially harmful and may be perceived as punitive. Hospitalists should consider consulting addiction or mental health specialists to assist with formulating a plan of care. However, such specialists may not be available in smaller or rural hospitals and referral at discharge can be challenging.53

Beginning to taper opioids during the hospitalization can be appropriate when patients are motivated and can transition to an outpatient provider who will supervise the taper. In ambulatory settings, tapers of 10% to 30% every 2 to 5 days are generally well tolerated.54 If patients started tapering opioids under supervision of an outpatient provider prior to hospitalization; ideally, the taper can be continued during hospitalization with close coordination with the outpatient clinician.

Unfortunately, many patients on LTOT are admitted with new sources of acute pain and or exacerbations of chronic pain, and some have concomitant substance use disorders; we plan to address the management of these complex situations in future work.

Despite the frequency with which patients on LTOT are hospitalized for nonsurgical stays and the challenges inherent in evaluating pain and assessing the possibility of substance use disorders, no formal guidelines or empirical research studies pertain to this population. Guidelines in this review were developed for hospital settings and acute pain in the absence of LTOT, and for outpatient care of patients on LTOT. We also included a nonsystematic synthesis of literature that varied in relevance to medical inpatients on LTOT.

CONCLUSIONS

Although inpatient assessment and treatment of patients with LTOT remains an underresearched area, we were able to extract and synthesize recommendations from 14 guideline statements and apply these to the assessment of patients with LTOT in the inpatient setting. Hospitalists frequently encounter patients on LTOT for chronic nonmalignant pain and are faced with complex decisions about the effectiveness and safety of LTOT; appropriate patient assessment is fundamental to making these decisions. Key guideline recommendations relevant to inpatient assessment include assessing both pain and functional status, differentiating acute from chronic pain, ascertaining preadmission pain treatment history, obtaining a psychosocial history, screening for mental health issues such as depression and anxiety, screening for substance use disorders, checking state prescription drug monitoring databases, ordering urine drug immunoassays, detecting use of sedative-hypnotics, identifying medical conditions associated with increased risk of overdose and adverse events, and appraising the potential benefits and harms of opioid therapy. Although approaches to assessing medical inpatients on LTOT can be extrapolated from outpatient guidelines, observational studies, and small studies in surgical populations, more work is needed to address these critical topics for inpatients on LTOT.

Disclosure

Dr. Herzig was funded by grant number K23AG042459 from the National Institute on Aging. The funding organization had no involvement in any aspect of the study, including design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. All other authors have no relevant conflicts of interest with the work.

Hospitalists face complex questions about how to evaluate and treat the large number of individuals who are admitted on long-term opioid therapy (LTOT, defined as lasting 3 months or longer) for chronic noncancer pain. A recent study at one Veterans Affairs hospital, found 26% of medical inpatients were on LTOT.1 Over the last 2 decades, use of LTOT has risen substantially in the United States, including among middle-aged and older adults.2 Concurrently, inpatient hospitalizations related to the overuse of prescription opioids, including overdose, dependence, abuse, and adverse drug events, have increased by 153%.3 Individuals on LTOT can also be hospitalized for exacerbations of the opioid-treated chronic pain condition or unrelated conditions. In addition to affecting rates of hospitalization, use of LTOT is associated with higher rates of in-hospital adverse events, longer hospital stays, and higher readmission rates.1,4,5

Physicians find managing chronic pain to be stressful, are often concerned about misuse and addiction, and believe their training in opioid prescribing is inadequate.6 Hospitalists report confidence in assessing and prescribing opioids for acute pain but limited success and satisfaction with treating exacerbations of chronic pain.7 Although half of all hospitalized patients receive opioids,5 little information is available to guide the care of hospitalized medical patients on LTOT for chronic noncancer pain.8,9

Our multispecialty team sought to synthesize guideline recommendations and primary literature relevant to the assessment of medical inpatients on LTOT to assist practitioners balance effective pain treatment and opioid risk reduction. This article addresses obtaining a comprehensive pain history, identifying misuse and opioid use disorders, assessing the risk of overdose and adverse drug events, gauging the risk of withdrawal, and based on such findings, appraise indications for opioid therapy. Other authors have recently published narrative reviews on the management of acute pain in hospitalized patients with opioid dependence and the inpatient management of opioid use disorder.10,11

METHODS

To identify primary literature, we searched PubMed, EMBASE, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Health Economic Evaluations Database, key meeting abstracts, and hand searches. To identify guidelines, we searched PubMed, National Guidelines Clearinghouse, specialty societies’ websites, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the United Kingdom National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the Canadian Medical Association, and the Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council. Search terms related to opioids and chronic pain, which was last updated in October 2016.12

We selected English-language documents on opioids and chronic pain among adults, excluding pain in the setting of procedures, labor and delivery, life-limiting illness, or specific conditions. For primary literature, we considered intervention studies of any design that addressed pain management among hospitalized medical patients. We included guidelines and specialty society position statements published after January 1, 2009, that addressed pain in the hospital setting, acute pain in any setting, or chronic pain in the outpatient setting if published by a national body. Due to the paucity of documents specific to inpatient care, we used a narrative review format to synthesize information. Dual reviewers extracted guideline recommendations potentially relevant to medical inpatients on LTOT. We also summarize relevant assessment instruments, emphasizing very brief screening instruments, which may be more likely to be used by busy hospitalists.

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

Obtaining a Comprehensive Pain History

Hospitalists newly evaluating patients on LTOT often face a dual challenge: deciding if the patient has an immediate indication for additional opioids and if the current long-term opioid regimen should be altered or discontinued. In general, opioids are an accepted short-term treatment for moderate to severe acute pain but their role in chronic noncancer pain is controversial. Newly released guidelines by the CDC recommend initiating LTOT as a last resort, and the Departments of Veterans Affairs and Defense guidelines recommend against initiation of LTOT.22,23

A key first step, therefore, is distinguishing between acute and chronic pain. Among patients on LTOT, pain can represent a new acute pain condition, an exacerbation of chronic pain, opioid-induced hyperalgesia, or opioid withdrawal. Acute pain is defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in relation to such damage.26 In contrast, chronic pain is a complex response that may not be related to actual or ongoing tissue damage, and is influenced by physiological, contextual, and psychological factors. Two acute pain guidelines and 1 chronic pain guideline recommend distinguishing acute and chronic pain,9,16,21 3 chronic pain guidelines reinforce the importance of obtaining a pain history (including timing, intensity, frequency, onset, etc),20,22,23 and 6 guidelines recommend ascertaining a history of prior pain-related treatments.9,13,14,16,20,22 Inquiring how the current pain compares with symptoms “on a good day,” what activities the patient can usually perform, and what the patient does outside the hospital to cope with pain can serve as entry into this conversation.

In addition to function, 5 guidelines, including 2 specific guidelines for acute pain or the hospital setting, recommend obtaining a detailed psychosocial history to identify life stressors and gain insight into the patient’s coping skills.14,16,19,20,22 Psychiatric symptoms can intensify the experience of pain or hamper coping ability. Anxiety, depression, and insomnia frequently coexist in patients with chronic pain.31 As such, 3 hospital setting/acute pain guidelines and 3 chronic pain guidelines recommend screening for mental health issues including anxiety and depression.13,14,16,20,22,23 Several depression screening instruments have been validated among inpatients,32 and there are validated single-item, self-administered instruments for both depression and anxiety (Table 3).32,33

Although obtaining a comprehensive history before making treatment decisions is ideal, some patients present in extremis. In emergency departments, some guidelines endorse prompt administration of analgesics based on patient self-report, prior to establishing a diagnosis.17 Given concerns about the growing prevalence of opioid use disorders, several states now recommend emergency medicine prescribers screen for misuse before giving opioids and avoid parenteral opioids for acute exacerbations of chronic pain.34 Treatments received in emergency departments set patients’ expectations for the care they receive during hospitalization, and hospitalists may find it necessary to explain therapies appropriate for urgent management are not intended to be sustained.

Identifying Misuse and Opioid Use Disorders

Nonmedical use of prescription opioids and opioid use disorders have more than doubled over the last decade.35 Five guidelines, including 3 specific guidelines for acute pain or the hospital setting, recommend screening for opioid misuse.13,14,16,19,23 Many states mandate practitioners assess patients for substance use disorders before prescribing controlled substances.36 Instruments to identify aberrant and risky use include the Current Opioid Misuse Measure,37 Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire,38 Addiction Behaviors Checklist,39 Screening Tool for Abuse,40 and the Self-Administered Single-Item Screening Question (Table 3).41 However, the evidence for these and other tools is limited and absent for the inpatient setting.21,42

In addition to obtaining a history from the patient, 4 guidelines specific to hospital settings/acute pain and 4 chronic pain guidelines recommend practitioners access prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs).13-16,19,21-24 PDMPs exist in all states except Missouri, and about half of states mandate practitioners check the PDMP database in certain circumstances.36 Studies examining the effects of PDMPs on prescribing are limited, but checking these databases can uncover concerning patterns including overlapping prescriptions or multiple prescribers.43 PDMPs can also confirm reported medication doses, for which patient report may be less reliable.

Two hospital/acute pain guidelines and 5 chronic pain guidelines also recommend urine drug testing, although differing on when and whom to test, with some favoring universal screening.11,20,23 Screening hospitalized patients may reveal substances not reported by patients, but medications administered in emergency departments can confound results. Furthermore, the commonly used immunoassay does not distinguish heroin from prescription opioids, nor detect hydrocodone, oxycodone, methadone, buprenorphine, or certain benzodiazepines. Chromatography/mass spectrometry assays can but are often not available from hospital laboratories. The differential for unexpected results includes substance use, self treatment of uncontrolled pain, diversion, or laboratory error.20

If concerning opioid use is identified, 3 hospital setting/acute pain specific guidelines and the CDC guideline recommend sharing concerns with patients and assessing for a substance use disorder.9,13,16,22 Determining whether patients have an opioid use disorder that meets the criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 5th Edition44 can be challenging. Patients may minimize or deny symptoms or fear that the stigma of an opioid use disorder will lead to dismissive or subpar care. Additionally, substance use disorders are subject to federal confidentiality regulations, which can hamper acquisition of information from providers.45 Thus, hospitalists may find specialty consultation helpful to confirm the diagnosis.

Assessing the Risk of Overdose and Adverse Drug Events

Oversedation, respiratory depression, and death can result from iatrogenic or self-administered opioid overdose in the hospital.5 Patient factors that increase this risk among outpatients include a prior history of overdose, preexisting substance use disorders, cognitive impairment, mood and personality disorders, chronic kidney disease, sleep apnea, obstructive lung disease, and recent abstinence from opioids.12 Medication factors include concomitant use of benzodiazepines and other central nervous system depressants, including alcohol; recent initiation of long-acting opioids; use of fentanyl patches, immediate-release fentanyl, or methadone; rapid titration; switching opioids without adequate dose reduction; pharmacokinetic drug–drug interactions; and, importantly, higher doses.12,22 Two guidelines specific to acute pain and hospital settings and 5 chronic pain guidelines recommend screening for use of benzodiazepines among patients on LTOT.13,14,16,18-20,22,21

The CDC guideline recommends careful assessment when doses exceed 50 mg of morphine equivalents per day and avoiding doses above 90 mg per day due to the heightened risk of overdose.22 In the hospital, 23% of patients receive doses at or above 100 mg of morphine equivalents per day,5 and concurrent use of central nervous system depressants is common. Changes in kidney and liver function during acute illness may impact opioid metabolism and contribute to overdose.

In addition to overdose, opioids are leading causes of adverse drug events during hospitalization.46 Most studies have focused on surgical patients reporting common opioid-related events as nausea/vomiting, pruritus, rash, mental status changes, respiratory depression, ileus, and urinary retention.47 Hospitalized patients may also exhibit chronic adverse effects due to LTOT. At least one-third of patients on LTOT eventually stop because of adverse effects, such as endocrinopathies, sleep disordered breathing, constipation, fractures, falls, and mental status changes.48 Patients may lack awareness that their symptoms are attributable to opioids and are willing to reduce their opioid use once informed, especially when alternatives are offered to alleviate pain.

Gauging the Risk of Withdrawal

Sudden discontinuation of LTOT by patients, practitioners, or intercurrent events can have unanticipated and undesirable consequences. Withdrawal is not only distressing for patients; it can be dangerous because patients may resort to illicit use, diversion of opioids, or masking opioid withdrawal with other substances such as alcohol. The anxiety and distress associated with withdrawal, or anticipatory fear about withdrawal, can undermine therapeutic alliance and interfere with processes of care. Reviewed guidelines did not offer recommendations regarding withdrawal risk or specific strategies for avoidance. There is no specific prior dose threshold or degree of reduction in opioids that puts patients at risk for withdrawal, in part due to patients’ beliefs, expectations, and differences in response to opioid formulations. Symptoms of opioid withdrawal have been compared to a severe case of influenza, including stomach cramps, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, tremor and muscle twitching, sweating, restlessness, yawning, tachycardia, anxiety and irritability, bone and joint aches, runny nose, tearing, and piloerection.49 The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS)49 and the Clinical Institute Narcotic Assessment51 are clinician-administered tools to assess opioid withdrawal similar to the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale, Revised,52 to monitor for withdrawal in the inpatient setting.

Synthesizing and Appraising the Indications for Opioid Therapy

For medical inpatients who report adequate pain control and functional outcomes on current doses of LTOT, without evidence of misuse, the pragmatic approach is to continue the treatment plan established by the outpatient clinician rather than escalating or tapering the dose. If opioids are prescribed at discharge, 3 hospital setting/acute pain guidelines and the CDC guideline recommend prescribing the lowest effective dose of immediate release opioids for 3 to 7 days.13,15,16,22

When patients exhibit evidence of an opioid use disorder, have a history of serious overdose, or are experiencing intolerable opioid-related adverse events, the hospitalist may conclude the harms of LTOT outweigh the benefits. For these patients, opioid treatment in the hospital can be aimed at preventing withdrawal, avoiding the perpetuation of inappropriate opioid use, managing other acute medical conditions, and communicating with outpatient prescribers. For patients with misuse, discontinuing opioids is potentially harmful and may be perceived as punitive. Hospitalists should consider consulting addiction or mental health specialists to assist with formulating a plan of care. However, such specialists may not be available in smaller or rural hospitals and referral at discharge can be challenging.53

Beginning to taper opioids during the hospitalization can be appropriate when patients are motivated and can transition to an outpatient provider who will supervise the taper. In ambulatory settings, tapers of 10% to 30% every 2 to 5 days are generally well tolerated.54 If patients started tapering opioids under supervision of an outpatient provider prior to hospitalization; ideally, the taper can be continued during hospitalization with close coordination with the outpatient clinician.

Unfortunately, many patients on LTOT are admitted with new sources of acute pain and or exacerbations of chronic pain, and some have concomitant substance use disorders; we plan to address the management of these complex situations in future work.

Despite the frequency with which patients on LTOT are hospitalized for nonsurgical stays and the challenges inherent in evaluating pain and assessing the possibility of substance use disorders, no formal guidelines or empirical research studies pertain to this population. Guidelines in this review were developed for hospital settings and acute pain in the absence of LTOT, and for outpatient care of patients on LTOT. We also included a nonsystematic synthesis of literature that varied in relevance to medical inpatients on LTOT.

CONCLUSIONS

Although inpatient assessment and treatment of patients with LTOT remains an underresearched area, we were able to extract and synthesize recommendations from 14 guideline statements and apply these to the assessment of patients with LTOT in the inpatient setting. Hospitalists frequently encounter patients on LTOT for chronic nonmalignant pain and are faced with complex decisions about the effectiveness and safety of LTOT; appropriate patient assessment is fundamental to making these decisions. Key guideline recommendations relevant to inpatient assessment include assessing both pain and functional status, differentiating acute from chronic pain, ascertaining preadmission pain treatment history, obtaining a psychosocial history, screening for mental health issues such as depression and anxiety, screening for substance use disorders, checking state prescription drug monitoring databases, ordering urine drug immunoassays, detecting use of sedative-hypnotics, identifying medical conditions associated with increased risk of overdose and adverse events, and appraising the potential benefits and harms of opioid therapy. Although approaches to assessing medical inpatients on LTOT can be extrapolated from outpatient guidelines, observational studies, and small studies in surgical populations, more work is needed to address these critical topics for inpatients on LTOT.

Disclosure

Dr. Herzig was funded by grant number K23AG042459 from the National Institute on Aging. The funding organization had no involvement in any aspect of the study, including design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. All other authors have no relevant conflicts of interest with the work.

1. Mosher HJ, Jiang L, Sarrazin MSV, Cram P, Kaboli PJ, Vander Weg MW. Prevalence and Characteristics of Hospitalized Adults on Chronic Opioid Therapy. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):82-87. PubMed

2. Campbell CI, Weisner C, Leresche L, et al. Age and Gender Trends in Long-Term Opioid Analgesic Use for Noncancer Pain. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2541-2547. PubMed

3. Owens PL, Barrett ML, Weiss AJ, Washington RE, Kronick R. Hospital Inpatient Utilization Related to Opioid Overuse among Adults, 1993–2012. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. PubMed

33. Young QR, Nguyen M, Roth S, Broadberry A, Mackay MH. Single-Item Measures for Depression and Anxiety: Validation of the Screening Tool for Psychological Distress in an Inpatient Cardiology Setting. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015;14(6):544-551. PubMed

1. Mosher HJ, Jiang L, Sarrazin MSV, Cram P, Kaboli PJ, Vander Weg MW. Prevalence and Characteristics of Hospitalized Adults on Chronic Opioid Therapy. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):82-87. PubMed

2. Campbell CI, Weisner C, Leresche L, et al. Age and Gender Trends in Long-Term Opioid Analgesic Use for Noncancer Pain. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2541-2547. PubMed

3. Owens PL, Barrett ML, Weiss AJ, Washington RE, Kronick R. Hospital Inpatient Utilization Related to Opioid Overuse among Adults, 1993–2012. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. PubMed

33. Young QR, Nguyen M, Roth S, Broadberry A, Mackay MH. Single-Item Measures for Depression and Anxiety: Validation of the Screening Tool for Psychological Distress in an Inpatient Cardiology Setting. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015;14(6):544-551. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Screening for depression in hospitalized medical patients

In our current healthcare system, pressure to provide cost- and time-efficient care is immense. Inpatient care often focuses on assessing the patient’s presenting illness or injury and treating that condition in a manner that gets the patient on their feet and out of the hospital quickly. Because depression is not an indication for hospitalization so long as active suicidality is absent, inpatient physicians may view it as a problem best managed in the outpatient setting. Yet both psychosocial and physical factors associated with depression put patients at risk for rehospitalization.1 Furthermore, hospitalization represents an unrecognized opportunity to optimize both mental and physical health outcomes.2

Indeed, poor physical and mental health often occur together. Depressed inpatients have poorer outcomes, increased length of stay, and greater vulnerability to hospital readmission.3,4 Among elderly hospitalized patients, depression is particularly common, especially in those with poor physical health, alcoholism,5 hip fracture, and stroke.6 Yet little is known about how often depression goes unrecognized, undiagnosed, and, therefore, untreated.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening for depression in the general adult population, including pregnant and postpartum women, and further suggests that screening should be implemented “with adequate systems in place to ensure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and appropriate follow-up.”2 The USPSTF guidelines do not distinguish between inpatient and outpatient settings. However, the preponderance of evidence for screening comes from outpatient care settings, and little is known about screening among inpatient populations.7

This study had 2 objectives. First, we sought to examine the performance of depression screening tools in inpatient settings. If depression screening were to become routine in hospital settings, screening tools would need to be sensitive and specific as well as brief and suitable for self-administration by patients or for administration by nurses, resident physicians, or hospitalists. It is also important to consider administration by mental health professionals, who may be best trained to administer such tests. We, therefore, examined 3 types of studies: (1) studies that tested a self-administered screening instrument, (2) studies that tested screening by individuals without formal training, and (3) studies that compared screening tools administered by mental health professionals. Second, we sought to describe associations between depression and clinical or utilization outcomes among hospitalized patients.

METHODS

We adhered to recommendations in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement,8,9 including designing the analysis before performing the review. However, we did not post a protocol in an online registry, formally assess study quality, or perform a meta-analysis.

Data Sources and Searches

We searched PsycINFO and PubMed databases for articles published between 1990 and 2016 (as of July 31, 2016). In PubMed, 2 search term strings were used to capture studies of depression screening tools in inpatient settings. The first used the advanced search option to exclude studies related to primary care settings or children and adolescents, and the second used MeSH terms to ensure that a wide variety of studies were included. Specific search terms are included in the Appendix. A similar search was conducted in the PsycINFO database and these search terms are also included in the Appendix.

Study Selection

Articles were eligible if they were published in English in peer-reviewed journals, included at least 20 adults hospitalized for nonpsychiatric reasons, and described the use of at least 1 measure of depression. The studies must have either tested the validity of a depression screening tool or examined the association between depression screening and clinical or utilization outcomes. Two investigators reviewed each title, abstract, and full-text article to determine eligibility, then reached a consensus on which studies to include in this review.

Data Extraction

Two investigators reviewed each full-text article to extract information related to study design, population, and outcomes regarding screening tool analysis or clinical results. From articles that assessed the performance of depression screening tools, we extracted information related to the nature and application of the index test, the nature and application of the reference test, the prevalence of depression, and the sensitivity and specificity of the index test compared with the reference test. For articles that focused on the association between depression screening and clinical or utilization outcomes, the data on relevant clinical outcomes included symptom severity, quality of life, and daily functioning, whereas the data on utilization outcomes included length of stay, readmission, and the cost of care.

RESULTS

Altogether, the search identified 3226 records. After eliminating duplicates and abstracts not suitable for inclusion (Figure), 101 articles underwent full-text review and 32 were found to be eligible. Of these, 12 focused on the association between depression and clinical or utilization outcomes, while 20 assessed the performance of depression screening tools.

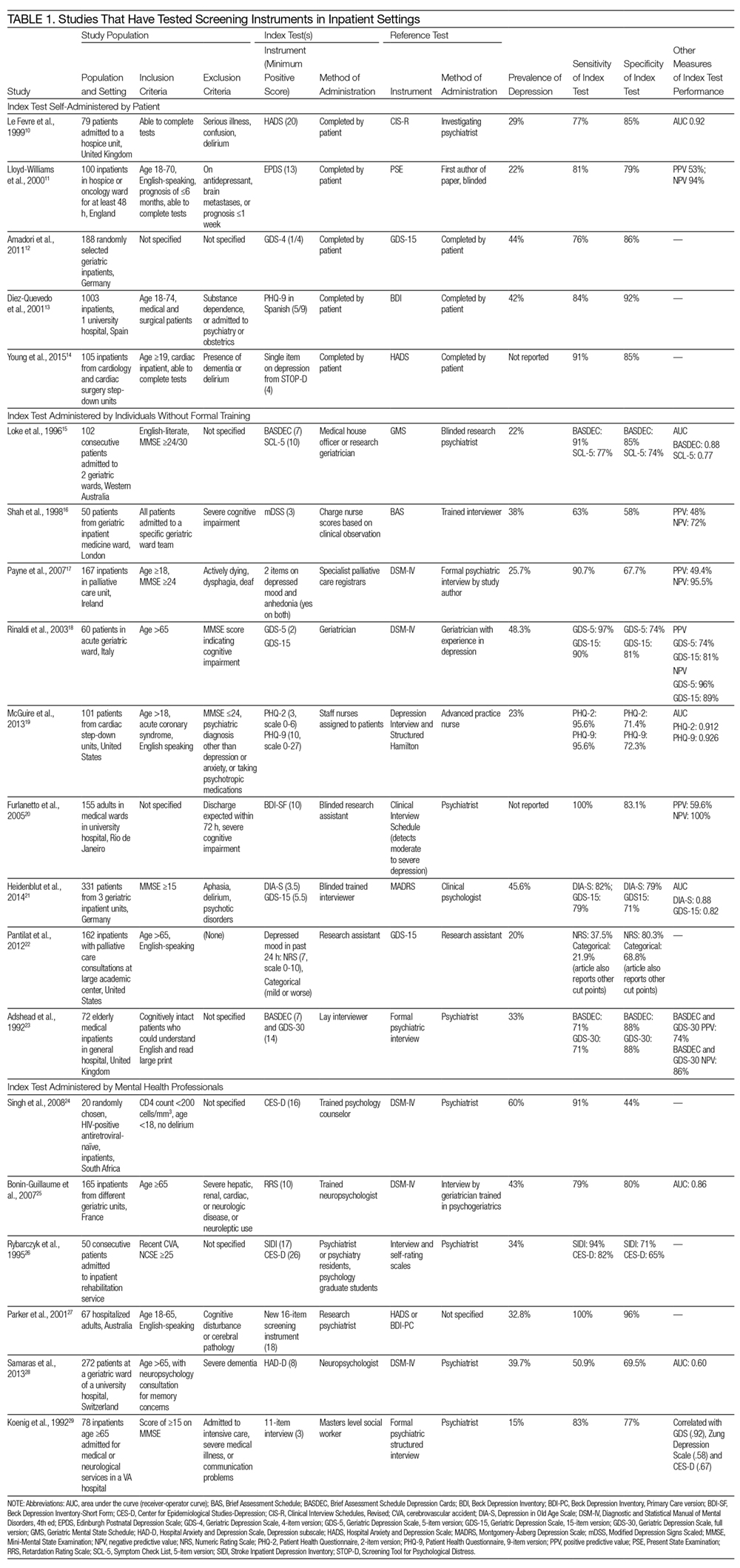

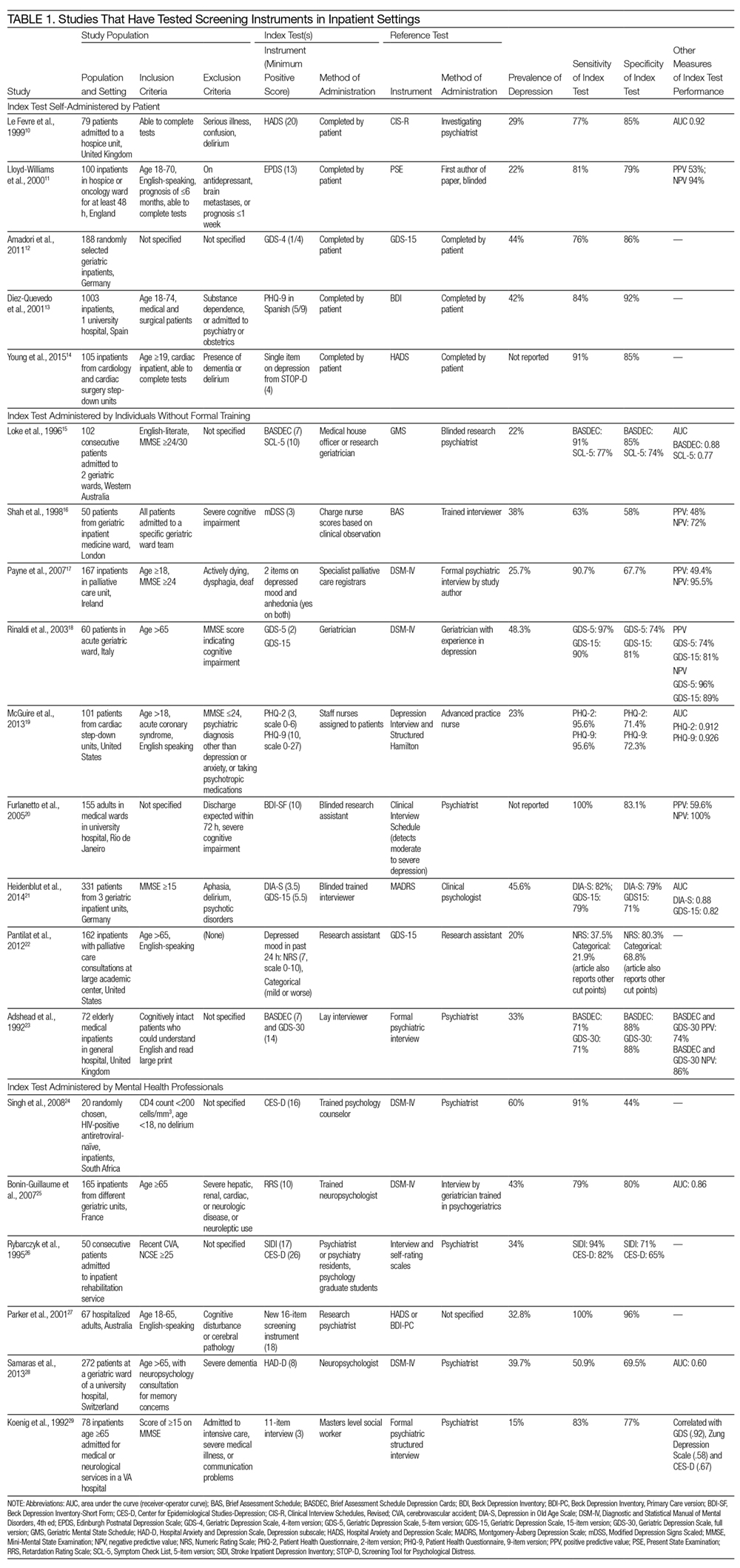

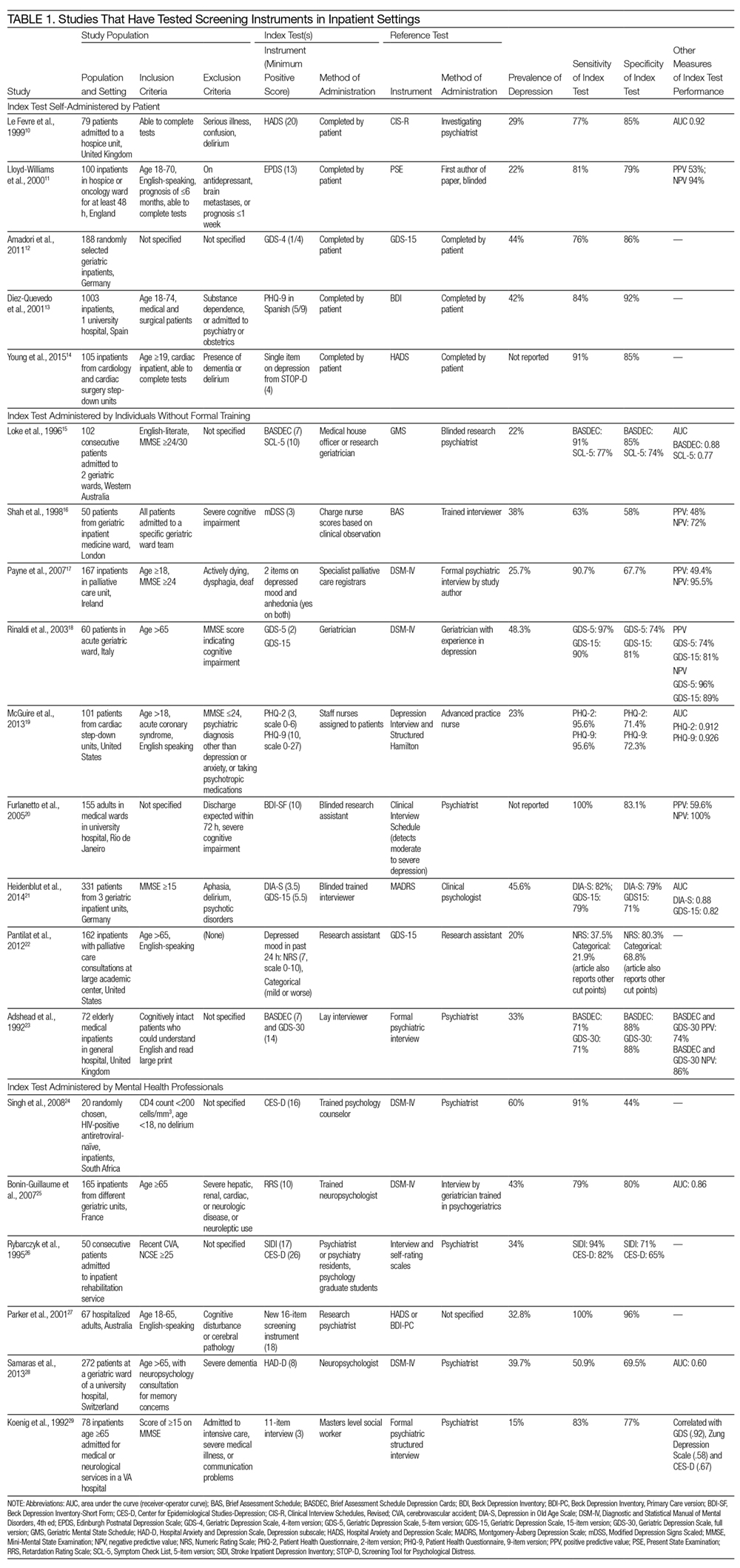

Depression Screening Tools

Table 1 describes the index and reference instruments as well as methods of administration, the prevalence of depression, and the sensitivity and specificity of the index instruments relative to the reference instruments. Across the 20 studies, the prevalence of depression ranged from 15% to 60%, with a median of 34%.10–29 This finding may reflect different methods of screening or variation among diverse hospitalized populations. Many of the studies excluded patients with cognitive impairment or communication barriers.

The included studies tested a wide range of unique instruments, and compared them with diverse reference standards. Five studies examined instruments that were self-administered by patients10–14; 9 studies assessed instruments administered by nurses, physicians, or research staff members without formal psychiatric training15–23; and 6 studies evaluated instruments administered by mental health professionals.24–29 Four studies compared different instruments that were administered in the same manner (eg, both self-administered by patients).12–14,22 In the remaining studies, both instruments and methods of administration differed between the index and reference conditions.

Eight studies tested brief instruments with 5 or fewer items, most of which exhibited good sensitivity (range 38%–91%) and specificity (range 68%–86%) relative to longer instruments.12,14–19,22 In 2 of these studies, instruments were self-administered. In 1 case, a single self-administered item from the STOP-D instrument (“Over the past 2 weeks, how much have you been bothered by feeling sad, down, or uninterested in life?”) performed nearly as well as the 14-item Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.14 In the other 6 studies testing brief instruments, the instruments were administered by individuals without formal training.15–19,22 In 1 such study, geriatricians asking 2 questions about depressed mood and anhedonia performed well compared with a formal psychiatric interview.17

Four studies tested variations of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS).12,18,21,23 In 3 of these studies, abbreviated versions of the GDS exhibited relatively high sensitivity and specificity.12,18,21 However, a study comparing the 15-item GDS (GDS-15) with the GDS-4 found that GDS-15 correctly classified 10% more patients with suspected depression.12 Two studies examined variations of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ). One study found that both the PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 obtained by staff nurses performed well relative to a comprehensive assessment by a trained advanced practice nurse.13,19

When reported, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and area under the receiver-operator curve were generally high.

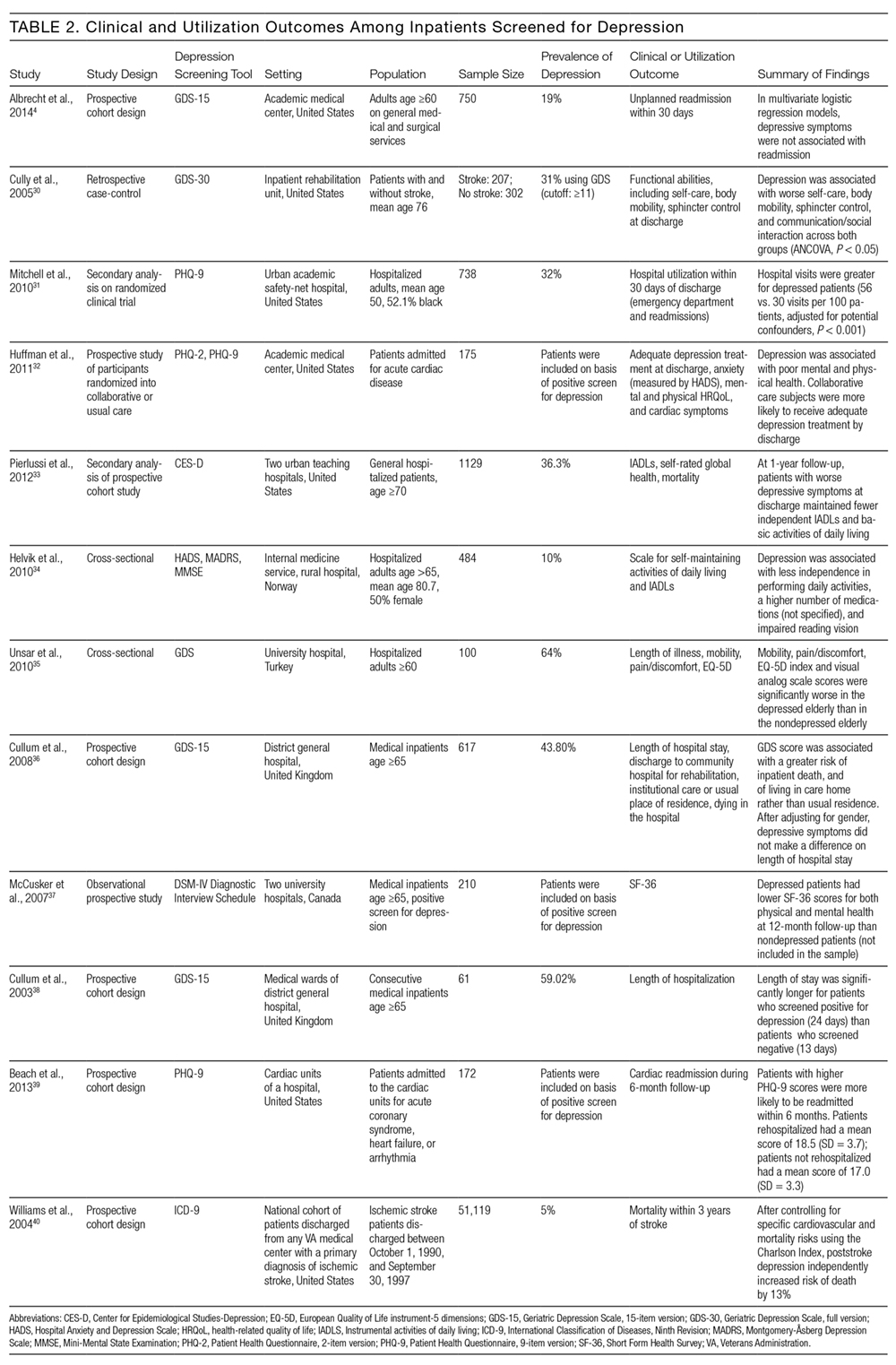

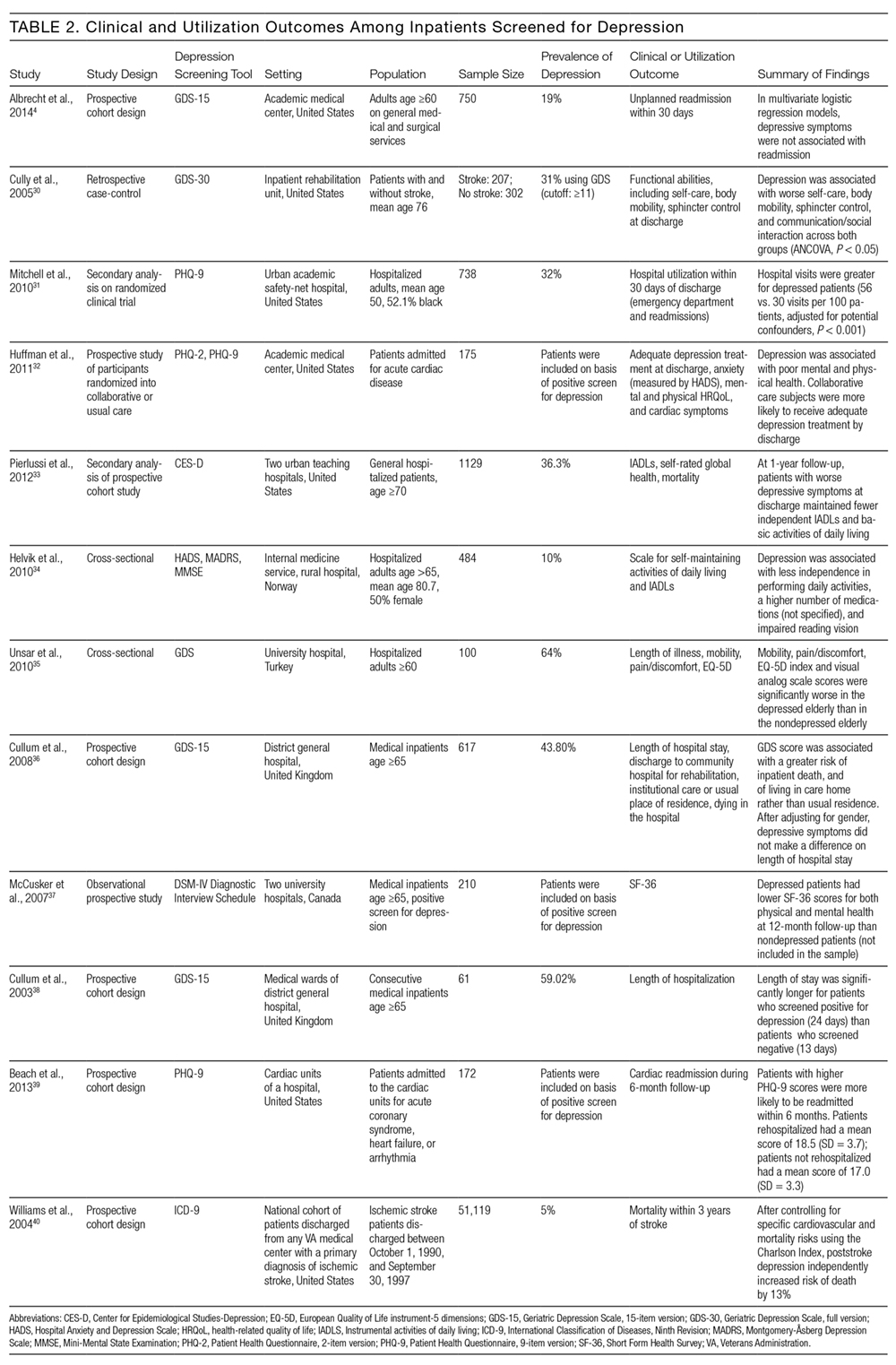

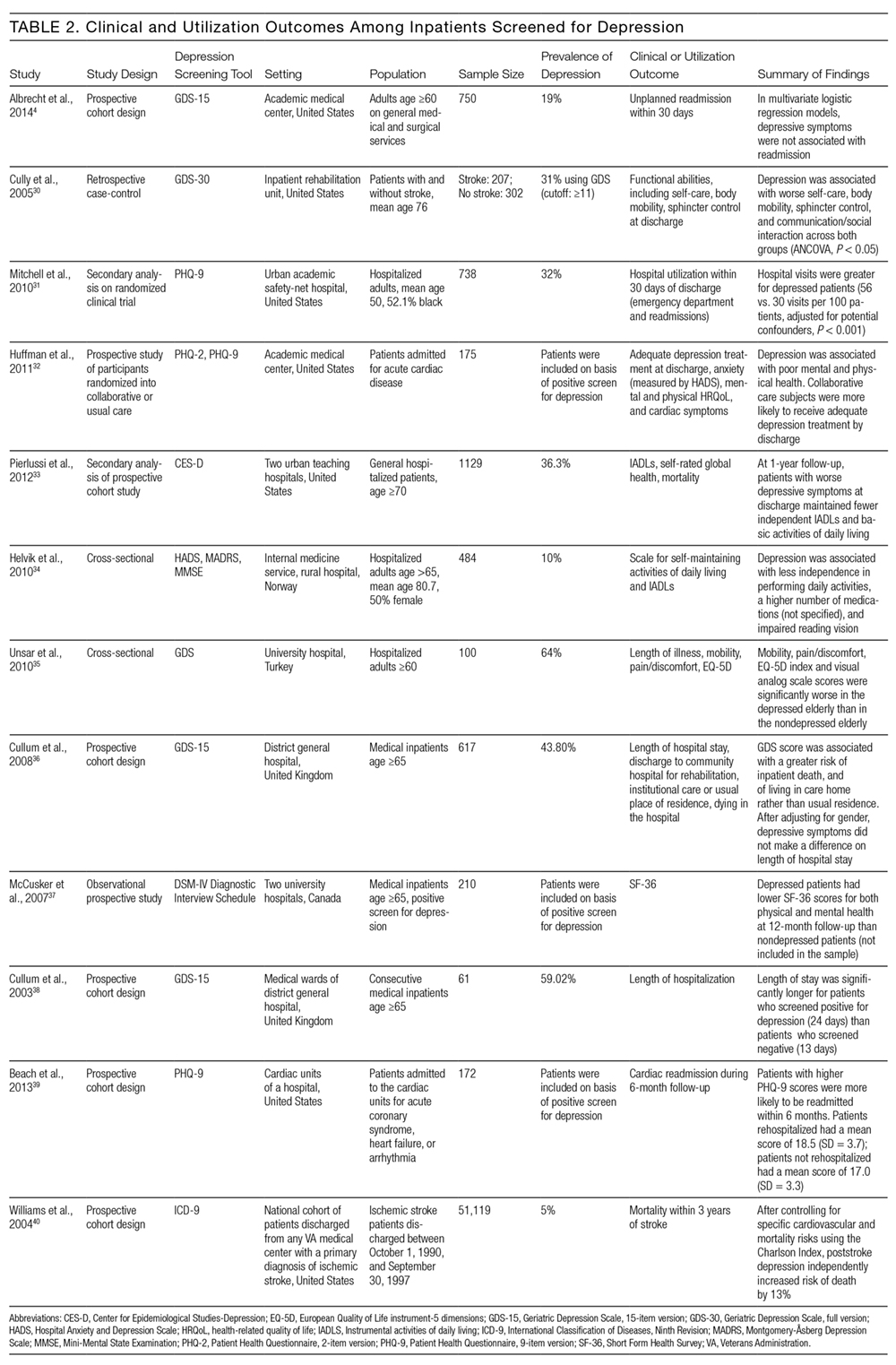

Depression and Clinical or Utilization Outcomes

Of the 12 studies that reported either clinical or utilization outcomes for depression screening in an inpatient setting,4,30–40 3 measured rates of rehospitalization.4,31,39 The other 9 studies tested for associations between symptoms of depression and either health or treatment outcomes. Table 2 provides a more detailed description of the study designs and results.

Other studies found that depression was associated with reduced functional abilities such as mobility and self-care,30,32–34 and increased hospital readmission31 as well as physical and mental health deficits.37 Interestingly, although 1 study did not find that depression and hospital readmission were closely linked (frequency at 19%), it found that comorbid illness and previous hospitalizations predicted readmission.4

We also evaluated the associations between depression diagnosed in the inpatient studies and 2 types of outcomes. The first type includes clinical outcomes including symptom severity, quality of life, and daily functioning. Most studies we identified assessed clinical outcomes, and all detected an association between depression and worse clinical outcomes. The second type includes healthcare utilization, which can be measured with the patients’ length of hospital stay, readmission and cost of care. In 1 such study, Mitchell aet al.31 reported a 54% increase in readmission within 30 days of discharge among patients who screened positive for depression.31 Additionally, Cully et al.30 found that depression may impinge on the recovery process of acute rehabilitation patients.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to describe the feasibility and performance of depression screening tools in inpatient medical settings, as well as associations between depression diagnosed in the inpatient setting and clinical and utilization outcomes. The median rate at which depression was detected among inpatients was 33%, ranging from 5% to 60%. Studies from several individual hospitals indicated that depression can be associated with higher healthcare utilization, including return to the hospital after discharge, as well as worse clinical outcomes. To detect undiagnosed depression among inpatients, screening appears feasible. Depression screening instruments generally exhibited good sensitivity and specificity relative to comprehensive clinical evaluations by mental health professionals. Furthermore, several self-administered and brief instruments had good performance. Prior authors have reported that screening for depression among inpatients may not be particularly burdensome to patients or staff members.41

The studies we reviewed used diverse screening instruments. Further research is needed to determine which tools are preferable in which patient populations, and to confirm that brief instruments are adequate for screening. The GDS is widely used, and many patients hospitalized in the United States fall into the geriatric group. The PHQ has been validated for self-administration and is widely used among outpatients42; it may be more suitable for younger populations. We found that several abbreviated versions of these and other screening instruments have exhibited good sensitivity and specificity among inpatients. However, many of the studies excluded patients with cognitive impairment or communication barriers. For individuals with auditory impairment, the Brief Assessment Schedule Depression Cards (BASDEC) might be an option. Used in 2 studies, the BASDEC involves showing patients a deck of 19 easy-to-read cards. The time required to administer the BASDEC is modest.15,23 Sets of smiley face diagrams might also be suitable for some patients with communication barriers or cognitive impairment. An ineligible study among stroke survivors found that selecting a sad face had a sensitivity of 76% and specificity of 77% relative to a formal diagnostic evaluation for depression.43

In considering the instruments that may be most suitable for inpatients, the role of somatic symptoms is also important because these can overlap between depression and the medical conditions that lead to hospitalization.44–46 Prior investigators found, for example, that 47% of Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) scores were attributable to somatic symptoms among patients hospitalized after myocardial infarction, whereas 37% of BDI scores were attributable to somatic symptoms among depressed outpatients.47 Future research is needed to determine the significance of somatic symptoms among inpatients, including whether they should be considered during screening, add prognostic value, or warrant specific treatment. In addition, although positive and negative predictive values were generally high among the screening instruments we evaluated, confirming the diagnosis of depression with a thorough clinical assessment is likely to be necessary.44,45

Despite the high prevalence of depression, associations with suboptimal outcomes, and the good performance of screening tools to date, screening for depression in the inpatient setting has received little attention. Prior authors have questioned whether hospital-based screening is an efficient and effective way to detect depression, and have raised valid concerns regarding false-positive diagnoses and unnecessary treatment, as well as a lack of randomized controlled trials.7,48,49 Whereas some studies suggest that depression is associated with greater healthcare utilization,3,4 little information exists regarding whether screening during hospitalization and treating previously undiagnosed depression improves clinical outcomes or reduces healthcare utilization.

Several important questions remain. What is the pathophysiology of depressed mood during hospitalization? How often does depressed mood during hospitalization reflect longstanding undiagnosed depression, longstanding undertreated depression, an acute stress disorder, or a normal if unpleasant short-term reaction to the stress of acute illnesses? Do the manifestations and effects of depressed mood differ among these situations? What is the prognosis of depressed mood occurring during hospitalization, and how many patients continue to have depression after recovery from acute illness; what factors affect prognosis? In a small sample of hospitalized patients, nearly 50% of those who had been depressed at intake remained depressed 1 month after discharge.50 Given that most antidepressant medications have to be taken for several weeks before effects can be detected, what, if any, approach to treatment should be taken? More research is needed on the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of diagnosing and treating depression in the inpatient setting.

This work has several limitations. We found relatively few studies meeting eligibility criteria, particularly studies assessing clinical and utilization outcomes among depressed inpatients. Among the screening tools that were studied in the hospital setting, the highly diverse instruments and modes of administration precluded a quantitative synthesis such as meta-analysis. Prior meta-analyses on specific screening tools have focused on outpatient populations.51–53 Furthermore, we did not evaluate study quality or risk of bias.

In conclusion, screening for depression in the inpatient setting via patient self-assessment or assessment by hospital staff appears feasible. Several brief screening tools are available that have good sensitivity and specificity relative to diagnoses made by mental health professionals. Limited evidence suggests that screening tools for depression may be ready to integrate into inpatient care.41 Yet, although depression appears to be common and associated with worse clinical outcomes and higher healthcare utilization, more research is needed on the benefits, risks, and potential costs of adding depression screening in the inpatient healthcare setting.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

1. Kahn KL, Keeler EB, Sherwood MJ, et al. Comparing outcomes of care before and after implementation of the DRG-based prospective payment system. JAMA. 1990;264(15):1984-1988. PubMed

2. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Screening for depression in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315(4):380-387. PubMed

3. Dennis M, Kadri A, Coffey J. Depression in older people in the general hospital: a systematic review of screening instruments. Age Ageing. 2012;41(2):148-154. PubMed

4. Albrecht JS, Gruber-Baldini AL, Hirshon JM, et al. Depressive symptoms and hospital readmission in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(3):495-499. PubMed

5. Grant BF, Hasin DS, Harford TC. Screening for major depression among alcoholics: an application of receiver operating characteristic analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1989;23(2):123-131. PubMed

6. Lieberman D, Galinsky D, Fried V, et al. Geriatric Depression Screening Scale (GDS) in patients hospitalized for physical rehabilitation. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14(7):549-555. PubMed

7. Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Recommendations on screening for depression in adults. CMAJ. 2013;185(9):775-782.

8. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. PubMed

9. Shea BJ, Hamel C, Wells GA, et al. AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1013-1020. PubMed

10. Le Fevre P, Devereux J, Smith S, Lawrie SM, Cornbleet M. Screening for psychiatric illness in the palliative care inpatient setting: a comparison between the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and the General Health Questionnaire-12. Palliat Med. 1999;13(5):399-407. PubMed

11. Lloyd-Williams M, Friedman T, Rudd N. Criterion validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale as a screening tool for depression in patients with advanced metastatic cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2000;20(4):259-265. PubMed

12. Amadori K, Herrmann E, Püllen RK. Comparison of the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) and the GDS-4 during screening for depression in an in-patient geriatric patient group. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(1):171-172. PubMed

13. Diez-Quevedo C, Rangil T, Sanchez-Planell L, Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. Validation and utility of the Patient Health Questionnaire in diagnosing mental disorders in 1003 general hospital Spanish inpatients. Psychosom Med. 2001;63(4):679-686. PubMed

14. Young Q-R, Nguyen M, Roth S, Broadberry A, Mackay MH. Single-item measures for depression and anxiety: validation of the screening tool for psychological distress in an inpatient cardiology setting. Eur J Cardiovasc Nursing. 2015;14(6):544-551. PubMed

15. Loke B, Nicklason F, Burvill P. Screening for depression: clinical validation of geriatricians’ diagnosis, the Brief Assessment Schedule Depression Cards and the 5-item version of the Symptom Check List among non-demented geriatric inpatients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1996;11(5):461-465.

16. Shah A, Karasu M, De T. Nursing staff and screening for depression among acutely ill geriatric inpatients: a pilot study. Aging Ment Health. 1998;2(1):71-74.

17. Payne A, Barry S, Creedon B, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of a two-question screening tool for depression in a specialist palliative care unit. Palliat Med. 2007;21(3):193-198. PubMed

18. Rinaldi P, Mecocci P, Benedetti C, et al. Validation of the five-item geriatric depression scale in elderly subjects in three different settings. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(5):694-698. PubMed

19. McGuire AW, Eastwood J, Macabasco-O’Connell A, Hays RD, Doering LV. Depression screening: utility of the Patient Health Questionnaire in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Am J Crit Care. 2013;22(1):12-19. PubMed

20. Furlanetto LM, Mendlowicz MV, Bueno JR. The validity of the Beck Depression Inventory-Short Form as a screening and diagnostic instrument for moderate and severe depression in medical inpatients. J Affect Disord. 2005;86(1):87-91. PubMed

21. Heidenblut S, Zank S. Screening for depression with the Depression in Old Age Scale (DIA-S) and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS15): diagnostic accuracy in a geriatric inpatient setting. GeroPsych (Bern). 2014;27(1):41. PubMed

22. Pantilat SZ, O’Riordan DL, Dibble SL, Landefeld CS. An assessment of the screening performance of a single-item measure of depression from the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale among chronically ill hospitalized patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43(5):866-873. PubMed

23. Adshead F, Cody DD, Pitt B. BASDEC: a novel screening instrument for depression in elderly medical inpatients. BMJ. 1992;305(6850):397. PubMed

24. Singh D, Sunpath H, John S, Eastham L, Gouden R. The utility of a rapid screening tool for depression and HIV dementia amongst patients with low CD4 counts – a preliminary report. Afr J Psychiatry (Johannesbg). 2008;11(4):282-286. PubMed

25. Bonin-Guillaume S, Sautel L, Demattei C, Jouve E, Blin O. Validation of the Retardation Rating Scale for detecting in geriatric inpatients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(1):68-76. PubMed