User login

Using Life Stories to Connect Veterans and Providers

Anyone involved with the U.S. health care system has heard one or more of the following dispiriting comments. If you are a patient, you have heard or said, “I wish I felt like my provider understood me. He/she just doesn’t have the time.” If you are a provider, you have heard yourself or another provider say, “I wish I had more time to get to know my patients as people. I could do a better job or at least I could remember them without looking at the chart.” This article describes a novel program—My Life, My Story—instituted at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital (WSMMVH) in Madison, Wisconsin. The program uses personal narratives to foster a sense of connection between providers and their veteran patients.

Related: Infusing Gerontologic Practice Into PACT

My Life, My Story had its origins in a small performance improvement project aimed at helping psychiatric residents learn about their new outpatients during rotation. The clinic staff wanted residents to get to know their patients as people in addition to understanding the veterans’ medical conditions. The veterans were first offered the opportunity to come to writers’ workshops and create personal narratives that would be shared later with their clinicians. Unfortunately, only a few veterans were willing to take on this task.

A more patient-friendly approach for collecting and sharing the stories was developed and funded by the VHA Office of Patient-Centered Care and Cultural Transformation (OPCC&CT). Veterans who chose to participate worked with an interviewer/writer to create a personal narrative, which was then shared with their patient aligned care team (PACT). Another component of the interview process was the Personal Health Inventory (PHI), a questionnaire developed by the OPCC&CT that helps veterans articulate their goals and motivations for physical, social, psychological, and spiritual well-being.1 The PHI and personal narrative were paired, to give health care providers (HCPs) a sense of the veteran and their personal health goals.

Background

The health benefits of telling or writing the story of a difficult emotional event have been demonstrated by Pennebaker.2 In varied groups, from prisoners to patients with chronic pain, the writing or talking about experiences improved mood and lowered distress. In addition, studies of medically ill patients showed a decline in physician visits in the 2 to 6 months following the narrative process.3,4 Improved immune response was also shown for patients with hepatitis B, HIV, asthma, and rheumatoid arthritis in response to completing a narrative.5-7

Related: Experiences of Veterans With Diabetes From Shared Medical Appointments

But the writing task is difficult for many people, especially those with advanced illness. Interviewing these patients and writing their stories is a way to give them a voice that otherwise might go unheard.

Dignity therapy with terminally ill patients, a technique developed by Dr. H.M. Chochinov, used an expert to collect the story by bedside interview and to produce a dignity-enhancing life narrative.8-10 Wise and colleagues modified this process for patients with cancer stages III and IV by using telephone interviews, which showed reduced anger, depression, tension, and an increased sense of peace.11 Personal narratives in which patients tell their story and receive it in written form have been shown to reduce psychological distress, increase hope, and help the patient feel valued.10,12

Pennebaker hypothesized that several mechanisms account for these improvements in health measures.2 First, developing a narrative provides a contextual understanding of stressful events. Creating a personal narrative allows a patient to identify and give meaning to life’s struggles. Through this process, coping is hypothesized to occur.13-15 Second, storytelling connects the teller with a wider audience.16

Another study by Pennebaker and colleagues found an improvement in social connectedness in college students in the days following the disclosure of emotional stories.17 The study speculates that nondisclosure fosters isolation, whereas disclosure connects us with others, helping us to reach out to others and improving a sense of feeling understood.

Methods

Project staff were recruited to conduct the interviews and write the stories. Team members with varied backgrounds and experiences were selected: a nurse at the WSMMVH who served as an army interrogator in Afghanistan; a professional counselor with prior experience working for the VA; and a marriage and family therapist with a poetry MA.

Providers were recruited for participation in the project through (1) presentations to nursing staff on the inpatient units where stories were gathered; (2) compilations of de-identified stories from veterans on those units were distributed; (3) presentations on the project at outpatient clinics, where the narratives of veterans who were patients at those clinics were read aloud; and (4) discussions of the program at monthly hospital-wide meetings.

Related: Diabetes Patient-Centered Medical Home Approach

Patients were recruited from 2 inpatient units and 1 long-term rehabilitative care unit. Interviewers introduced themselves to the veterans, described the project, and gave each one a project brochure. Veterans were given the opportunity to be interviewed immediately, schedule a future interview, decide later, or not participate.

The majority of veterans who participated chose to be interviewed immediately. Scheduling interviews around procedures and discharges on busy inpatient units proved difficult. Overall participation rate was high: 60% of veterans who were told about the project eventually told their story.

Interview Process

Veterans signed a consent form before the interview, and the interviews were recorded on a digital audio recorder. They were informed they could choose to talk—or not talk—about any part of their life, the interviewer would write a draft of the story based on the interview and bring it back for their review, and the story would not be added to their patient record until they gave their approval. Spouses/partners were invited to participate if they desired.

Interviewers were encouraged to follow the lead of the veteran. Those who were clinicians were encouraged to “take off their clinician hat” during the interview. Unless guided otherwise by the veteran, the interview was semichronological and included the following subjects: birth and childhood, family, schooling, military service, relationships and/or marriage, children, career and employment, general health, and current hospital stay and presenting problem.

Interviews lasted about an hour, and 182 interviews were conducted. Interviews were frequently interrupted by HCPs who checked vitals, administering medications, rounding with residents, and so forth. If the HCP indicated that the patient could keep talking, the interview continued. If the patient had to leave the room for a procedure or medical appointment, the interviewer paused the recording and scheduled a time to come back and complete the interview.

After the interview, veterans were told that they could expect to see the first written draft of their story within 2 days. Veterans who were to be discharged the day of the interview or the following day were told that the story would be sent to them in the mail to review at home.

Personal Health Inventory

Interviewers introduced the PHI to veterans as an opportunity to identify their wellness goals and share these with the PACT. Veterans with late-stage cancer or in hospice care were given the option to skip the PHI. Of the 103 veterans who completed the PHI, 96 chose to have the interviewer read the questions and record their answers; only 7 chose to complete the PHI on their own.

One hundred eighty-two veterans completed personal narratives, and 103 completed the PHI. Incomplete PHIs occurred for the following reasons: hospice or end of life, 12; declined, 20; could not complete, 21; discharged, 19; lost to follow-up, 7.

Writing

The quality of the written stories was critical to the success of the project. Creativity was encouraged to produce stories that captured and brought to life the voice and spirit of the interview subject. The team identified the following features of a good story: (1) written in the first person; (2) nonjudgmental; (3) captures the voice of the veteran; (4) accurately reflects the content of the interview; and (5) nondiagnostic (not labeling).

A short story format was used to increase the likelihood that busy providers would read the narratives. Writers were encouraged to limit the length of the stories to 1 to 2 printed pages (650-1,300 words). Completed stories ranged from 95 words to 2,345 words with an average length of 1,053 words. Veterans wrote 3 and the interviewers wrote 178 narratives; 1 narrative was written by a team member who was not present during the interview but listened to the audio recording.

Editing Process

The first draft of the story was printed and given to the veteran to make any desired changes. Veterans reviewed and updated their stories in different ways. Some wrote their changes on the printed copy and had the writer return at a later time to pick it up. Others read through the story with the writer present and wrote their changes on the printed copy. Some had the writer read the story aloud and alerted the writer when an item needed changing.

Drafts were mailed to already discharged veterans, including a postage-paid return envelope to allow them to mail their changes to the team. After incorporating the veteran’s changes, the team member brought back a second draft of the story for the veteran to review. This process was repeated until the veteran gave final approval. Veterans could then approve whether to share their story with their PACT via the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS).

Some participant attrition occurred at this point. Six veterans requested that their stories not go in the CPRS (although 3 of them requested printed copies). One veteran changed his mind after his story was added to the CPRS; the team then immediately removed it. Two veterans died shortly after being released from the hospital and before they could review their stories. The families of both these veterans requested that an audio file of the interview be mailed to them.

Sharing With Family and Providers

Veterans received a printed copy of the approved story and the option to have additional copies for family members. The average number of additional copies requested was 3. Family and friends responded positively to the interview process and stories. Spouses who sat in on the interviews always added something to the interview process, and some were active participants. Eight of the 182 stories were dual narratives that included the words of the veteran and his/her spouse.

Providers were alerted to the personal narratives and PHI via CPRS. The completed story was added to the veteran’s record with the title “My Story.” The story was then electronically cosigned to the veteran’s inpatient and outpatient PACT. Typically, this included 4 people: the inpatient resident and attending physician and the outpatient provider and nurse care manager. If other providers were directly involved in the care of the veteran (mental health, specialists, surgeons), they were also cosigned to the story. If a veteran received primary care outside WSMMVH, their PACT was notified of the presence of the story in CPRS (and given a copy) via encrypted e-mail, in the CPRS “Postings” section.

Program Feedback

The original interviewer/writer team members (2.5 full-time employee equivalent for 6 months) generated 182 stories. The corresponding My Story notes in the CPRS were cosigned to an average of 3.3 providers. The program received both formal (solicited) feedback and informal (unsolicited) feedback from veterans and providers.

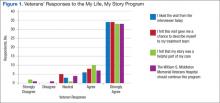

After gathering the first 80 stories, the team solicited participant satisfaction data from interviewed veterans, using a 5-point Likert-type scale. Veteran reaction was positive (Figure 1). The team polled VA providers with an online anonymous survey, using the same Likert-type scale to see whether the story and PHI were useful to providers in their clinical practice. The results suggested they were (Figure 2).

Perhaps the most enlightening and touching feedback were the following unsolicited e-mails and comments:

- I have so appreciated these stories, especially because they immediately become a source of connection with the veterans who come in (some for the first time) to see me about their heart failure. In the midst of a heavy “clinical” topic, knowing their stories has helped us form a stronger patient-provider relationship. It has provided moments of levity and a clear way to tell the patient that I am connecting with them and they are important. —VA employee

- I’m a veteran, and I love reading the real stories of veterans, told in their own words. For us, it’s always wonderful to feel like someone is listening. It’s good to feel like someone wants to hear what you’ve traveled through to get where you are. For those of us who put our lives, our health, our relationships, and our honor on the line for so many others, it’s great when someone will just take the time to listen and understand. It most definitely is very healing. —VA employee

- This is a great way to improve provider understanding and decrease bias and eliminate first impression issues, as people are generally ill and cranky when seeking medical care. —Veteran

- The My Story note was wonderful. I truly feel it has helped me to understand my patients better and to know where they are coming from. This is invaluable to the VA where experiences shape our patients in such a profound way. —VA employee

Recent developments at the WSMMVH suggest that veteran stories are becoming an accepted component of clinical care. The heart/lung transplant team requested that the My Story note be part of the transplant workup process for all new patients. The team also found that new HCPs who were assigned to a veteran regularly cosign that veteran’s My Story note to other providers on the care team. In addition, My Story referrals come from all types of HCPs and staff, both within the hospital and at primary care clinics.

Recent Developments

Two WSMMVH employees suggested using volunteers to gather stories and became the first volunteers: One was a housekeeper who had served in the U.S. Army during the Gulf War, and the other was a registered nurse; both had writing experience.

In 2014, staff trained 12 volunteers from the local community who have been trained to interview and write stories. The volunteers have varied professional backgrounds. All have a background and interest in writing or experience working in a health care setting; 2 are veterans. These volunteers are adding to the team at no additional cost. In development is a standardized training program and a method to look at story collection and writing fidelity, which will allow for further expansion of this program.

My Life, My Story continues to expand significantly. A total of 610 veterans have been interviewed, and 348 of these interviews were conducted by volunteers. The project now has 18 active volunteers with 4 more on a waiting list. A pilot has been launched at a WSMMVH outpatient clinic, which interviews VA primary care providers about their life stories and shares them with their veteran patients. There is now collaboration with the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison to offer a 2-week My Story elective to fourth-year medical students in spring 2016. In March 2015, My Life, My Story expanded to 6 pilot facilities across the VA: Asheville, North Carolina; Bronx, New York; Iowa City, Iowa; Reno, Nevada; Topeka, Kansas; and White River Junction, Vermont.

Future Projects

- The team is currently analyzing the themes appearing in veteran stories, using grounded theory methodology

- The process for outpatients is being revised, using phone calls and telehealth modalities to collect stories

- The team members are examining relationships between themes in stories and health/wellness goals identified on the PHI

- Eventually, the team will study how this process might improve the veteran/provider relationship on measures of satisfaction with care, quality of care, and health outcomes. The authors will also assess the effects of this process on provider satisfaction and burnout

Conclusion

Veteran stories, when skillfully elicited and carefully crafted, give providers an opportunity to know their patients better, without impinging on their time. For veterans, the experience of being interviewed and the knowledge that their story will be shared with providers is an important recognition that they matter and have a voice in their health care. In a world of high-technology health care, where time is the only thing in short supply, My Life, My Story leverages the old-world technology of storytelling to bring providers and patients closer together.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Amanda Hall and Jessica Jones who were interviewer/writers on the initial project. Both contributed immeasurably to the design and success of the project. The authors would also like to acknowledge Matt Spira who was our first volunteer interviewer and gave us the inspiration to recruit more volunteers. Volunteer Mary Johnston interviewed and wrote the sample veteran story in this article. We would also like to thank the nursing staff on 4A, 4B, and the community living center for their patience when we were in the way and for their support of the project. Last and most important, we would like to thank the veterans who were interviewed for this project. We have all learned more than we could have imagined from the stories that you shared with us. Your sacrifice, courage, and dedication both in the military and your personal lives are truly an inspiration. Thank you.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Veterans Health Administration, Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation. My Story Personal Health Inventory, Revision 20. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www .va.gov/patientcenteredcare/docs/va-opcc-personal -health-inventory-final-508.pdf. Revised October 7, 2013. Accessed May 11, 2015.

2. Pennebaker JW. Telling stories: the health benefits of narrative. Lit Med. 2000;19(1):3-18.

3. Greenberg MA, Stone AA. Writing about disclosed versus undisclosed traumas: immediate and long term effects on mood and health. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63:75-84.

4. Pennebaker JW, Beall SK. Confronting a traumatic event: toward an understanding of inhibition and disease. J Abnorm Psychol. 1986;95(3):274-281.

5. Petrie KJ, Booth RJ, Pennebaker JW, Davidson KP, Thomas MG. Disclosure of trauma and immune response to hepatitis B vaccination program. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63(5):787-792.

6. Petrie KJ, Fontanilla I, Thomas MG, Booth RJ, Pennebaker JW. Effect of written emotional expression on immune function in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: a randomized trial. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(2):272-275.

7. Smyth JM, Stone AA, Hurewitz A, Kaell A. Effects of writing about stressful experiences on symptom reduction in patients with asthma or rheumatoid arthritis. JAMA. 1999;281(14):1304-1309.

8. Chochinov HM. Dignity-conserving care—a new model for palliative care: helping the patient feel valued. JAMA. 2002;287(17):2253-2260.

9. Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, McClement S, Harlos M. Understanding the will to live in patients near death. Psychosom. 2005;46(1):7-10.

10. Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Breitbart W, et al. Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(8):753-762.

11. Wise M, Marchand L, Roberts LJ, Chih M. Existential suffering in advanced cancer: the buffering effects of narrative: a randomized control trial. Poster presented at: University of Washington School of Medicine 6th Annual Department Fair; April 8, 2015; Seattle, Washington.

12. Hall S, Goddard C, Opio D, Speck PW, Martin P, Higginson IJ. A novel approach to enhancing hope in patients with advanced cancer: a randomised phase II trial of dignity therapy. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2011;1(3):315-321.

13. Heiney SP. The healing power of story. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22(6):899-904.

14. Hyden L-C. Illness and narrative. Soc Health Illness. 1997;19(1):48-69.

15. Carlick A, Biley FC. Thoughts on the therapeutic use of narrative in the promotion of coping in cancer care. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2004;13(4):308-317.

16. Niederhoffer KG, Pennebaker JW. Sharing one’s story: on the benefits of writing or talking about emotional experience. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ, eds. Handbook of Positive Psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001:573-583.

17. Pennebaker JW, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R. Disclosure of traumas and immune function: health implications for psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988:56(2):239-245.

Anyone involved with the U.S. health care system has heard one or more of the following dispiriting comments. If you are a patient, you have heard or said, “I wish I felt like my provider understood me. He/she just doesn’t have the time.” If you are a provider, you have heard yourself or another provider say, “I wish I had more time to get to know my patients as people. I could do a better job or at least I could remember them without looking at the chart.” This article describes a novel program—My Life, My Story—instituted at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital (WSMMVH) in Madison, Wisconsin. The program uses personal narratives to foster a sense of connection between providers and their veteran patients.

Related: Infusing Gerontologic Practice Into PACT

My Life, My Story had its origins in a small performance improvement project aimed at helping psychiatric residents learn about their new outpatients during rotation. The clinic staff wanted residents to get to know their patients as people in addition to understanding the veterans’ medical conditions. The veterans were first offered the opportunity to come to writers’ workshops and create personal narratives that would be shared later with their clinicians. Unfortunately, only a few veterans were willing to take on this task.

A more patient-friendly approach for collecting and sharing the stories was developed and funded by the VHA Office of Patient-Centered Care and Cultural Transformation (OPCC&CT). Veterans who chose to participate worked with an interviewer/writer to create a personal narrative, which was then shared with their patient aligned care team (PACT). Another component of the interview process was the Personal Health Inventory (PHI), a questionnaire developed by the OPCC&CT that helps veterans articulate their goals and motivations for physical, social, psychological, and spiritual well-being.1 The PHI and personal narrative were paired, to give health care providers (HCPs) a sense of the veteran and their personal health goals.

Background

The health benefits of telling or writing the story of a difficult emotional event have been demonstrated by Pennebaker.2 In varied groups, from prisoners to patients with chronic pain, the writing or talking about experiences improved mood and lowered distress. In addition, studies of medically ill patients showed a decline in physician visits in the 2 to 6 months following the narrative process.3,4 Improved immune response was also shown for patients with hepatitis B, HIV, asthma, and rheumatoid arthritis in response to completing a narrative.5-7

Related: Experiences of Veterans With Diabetes From Shared Medical Appointments

But the writing task is difficult for many people, especially those with advanced illness. Interviewing these patients and writing their stories is a way to give them a voice that otherwise might go unheard.

Dignity therapy with terminally ill patients, a technique developed by Dr. H.M. Chochinov, used an expert to collect the story by bedside interview and to produce a dignity-enhancing life narrative.8-10 Wise and colleagues modified this process for patients with cancer stages III and IV by using telephone interviews, which showed reduced anger, depression, tension, and an increased sense of peace.11 Personal narratives in which patients tell their story and receive it in written form have been shown to reduce psychological distress, increase hope, and help the patient feel valued.10,12

Pennebaker hypothesized that several mechanisms account for these improvements in health measures.2 First, developing a narrative provides a contextual understanding of stressful events. Creating a personal narrative allows a patient to identify and give meaning to life’s struggles. Through this process, coping is hypothesized to occur.13-15 Second, storytelling connects the teller with a wider audience.16

Another study by Pennebaker and colleagues found an improvement in social connectedness in college students in the days following the disclosure of emotional stories.17 The study speculates that nondisclosure fosters isolation, whereas disclosure connects us with others, helping us to reach out to others and improving a sense of feeling understood.

Methods

Project staff were recruited to conduct the interviews and write the stories. Team members with varied backgrounds and experiences were selected: a nurse at the WSMMVH who served as an army interrogator in Afghanistan; a professional counselor with prior experience working for the VA; and a marriage and family therapist with a poetry MA.

Providers were recruited for participation in the project through (1) presentations to nursing staff on the inpatient units where stories were gathered; (2) compilations of de-identified stories from veterans on those units were distributed; (3) presentations on the project at outpatient clinics, where the narratives of veterans who were patients at those clinics were read aloud; and (4) discussions of the program at monthly hospital-wide meetings.

Related: Diabetes Patient-Centered Medical Home Approach

Patients were recruited from 2 inpatient units and 1 long-term rehabilitative care unit. Interviewers introduced themselves to the veterans, described the project, and gave each one a project brochure. Veterans were given the opportunity to be interviewed immediately, schedule a future interview, decide later, or not participate.

The majority of veterans who participated chose to be interviewed immediately. Scheduling interviews around procedures and discharges on busy inpatient units proved difficult. Overall participation rate was high: 60% of veterans who were told about the project eventually told their story.

Interview Process

Veterans signed a consent form before the interview, and the interviews were recorded on a digital audio recorder. They were informed they could choose to talk—or not talk—about any part of their life, the interviewer would write a draft of the story based on the interview and bring it back for their review, and the story would not be added to their patient record until they gave their approval. Spouses/partners were invited to participate if they desired.

Interviewers were encouraged to follow the lead of the veteran. Those who were clinicians were encouraged to “take off their clinician hat” during the interview. Unless guided otherwise by the veteran, the interview was semichronological and included the following subjects: birth and childhood, family, schooling, military service, relationships and/or marriage, children, career and employment, general health, and current hospital stay and presenting problem.

Interviews lasted about an hour, and 182 interviews were conducted. Interviews were frequently interrupted by HCPs who checked vitals, administering medications, rounding with residents, and so forth. If the HCP indicated that the patient could keep talking, the interview continued. If the patient had to leave the room for a procedure or medical appointment, the interviewer paused the recording and scheduled a time to come back and complete the interview.

After the interview, veterans were told that they could expect to see the first written draft of their story within 2 days. Veterans who were to be discharged the day of the interview or the following day were told that the story would be sent to them in the mail to review at home.

Personal Health Inventory

Interviewers introduced the PHI to veterans as an opportunity to identify their wellness goals and share these with the PACT. Veterans with late-stage cancer or in hospice care were given the option to skip the PHI. Of the 103 veterans who completed the PHI, 96 chose to have the interviewer read the questions and record their answers; only 7 chose to complete the PHI on their own.

One hundred eighty-two veterans completed personal narratives, and 103 completed the PHI. Incomplete PHIs occurred for the following reasons: hospice or end of life, 12; declined, 20; could not complete, 21; discharged, 19; lost to follow-up, 7.

Writing

The quality of the written stories was critical to the success of the project. Creativity was encouraged to produce stories that captured and brought to life the voice and spirit of the interview subject. The team identified the following features of a good story: (1) written in the first person; (2) nonjudgmental; (3) captures the voice of the veteran; (4) accurately reflects the content of the interview; and (5) nondiagnostic (not labeling).

A short story format was used to increase the likelihood that busy providers would read the narratives. Writers were encouraged to limit the length of the stories to 1 to 2 printed pages (650-1,300 words). Completed stories ranged from 95 words to 2,345 words with an average length of 1,053 words. Veterans wrote 3 and the interviewers wrote 178 narratives; 1 narrative was written by a team member who was not present during the interview but listened to the audio recording.

Editing Process

The first draft of the story was printed and given to the veteran to make any desired changes. Veterans reviewed and updated their stories in different ways. Some wrote their changes on the printed copy and had the writer return at a later time to pick it up. Others read through the story with the writer present and wrote their changes on the printed copy. Some had the writer read the story aloud and alerted the writer when an item needed changing.

Drafts were mailed to already discharged veterans, including a postage-paid return envelope to allow them to mail their changes to the team. After incorporating the veteran’s changes, the team member brought back a second draft of the story for the veteran to review. This process was repeated until the veteran gave final approval. Veterans could then approve whether to share their story with their PACT via the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS).

Some participant attrition occurred at this point. Six veterans requested that their stories not go in the CPRS (although 3 of them requested printed copies). One veteran changed his mind after his story was added to the CPRS; the team then immediately removed it. Two veterans died shortly after being released from the hospital and before they could review their stories. The families of both these veterans requested that an audio file of the interview be mailed to them.

Sharing With Family and Providers

Veterans received a printed copy of the approved story and the option to have additional copies for family members. The average number of additional copies requested was 3. Family and friends responded positively to the interview process and stories. Spouses who sat in on the interviews always added something to the interview process, and some were active participants. Eight of the 182 stories were dual narratives that included the words of the veteran and his/her spouse.

Providers were alerted to the personal narratives and PHI via CPRS. The completed story was added to the veteran’s record with the title “My Story.” The story was then electronically cosigned to the veteran’s inpatient and outpatient PACT. Typically, this included 4 people: the inpatient resident and attending physician and the outpatient provider and nurse care manager. If other providers were directly involved in the care of the veteran (mental health, specialists, surgeons), they were also cosigned to the story. If a veteran received primary care outside WSMMVH, their PACT was notified of the presence of the story in CPRS (and given a copy) via encrypted e-mail, in the CPRS “Postings” section.

Program Feedback

The original interviewer/writer team members (2.5 full-time employee equivalent for 6 months) generated 182 stories. The corresponding My Story notes in the CPRS were cosigned to an average of 3.3 providers. The program received both formal (solicited) feedback and informal (unsolicited) feedback from veterans and providers.

After gathering the first 80 stories, the team solicited participant satisfaction data from interviewed veterans, using a 5-point Likert-type scale. Veteran reaction was positive (Figure 1). The team polled VA providers with an online anonymous survey, using the same Likert-type scale to see whether the story and PHI were useful to providers in their clinical practice. The results suggested they were (Figure 2).

Perhaps the most enlightening and touching feedback were the following unsolicited e-mails and comments:

- I have so appreciated these stories, especially because they immediately become a source of connection with the veterans who come in (some for the first time) to see me about their heart failure. In the midst of a heavy “clinical” topic, knowing their stories has helped us form a stronger patient-provider relationship. It has provided moments of levity and a clear way to tell the patient that I am connecting with them and they are important. —VA employee

- I’m a veteran, and I love reading the real stories of veterans, told in their own words. For us, it’s always wonderful to feel like someone is listening. It’s good to feel like someone wants to hear what you’ve traveled through to get where you are. For those of us who put our lives, our health, our relationships, and our honor on the line for so many others, it’s great when someone will just take the time to listen and understand. It most definitely is very healing. —VA employee

- This is a great way to improve provider understanding and decrease bias and eliminate first impression issues, as people are generally ill and cranky when seeking medical care. —Veteran

- The My Story note was wonderful. I truly feel it has helped me to understand my patients better and to know where they are coming from. This is invaluable to the VA where experiences shape our patients in such a profound way. —VA employee

Recent developments at the WSMMVH suggest that veteran stories are becoming an accepted component of clinical care. The heart/lung transplant team requested that the My Story note be part of the transplant workup process for all new patients. The team also found that new HCPs who were assigned to a veteran regularly cosign that veteran’s My Story note to other providers on the care team. In addition, My Story referrals come from all types of HCPs and staff, both within the hospital and at primary care clinics.

Recent Developments

Two WSMMVH employees suggested using volunteers to gather stories and became the first volunteers: One was a housekeeper who had served in the U.S. Army during the Gulf War, and the other was a registered nurse; both had writing experience.

In 2014, staff trained 12 volunteers from the local community who have been trained to interview and write stories. The volunteers have varied professional backgrounds. All have a background and interest in writing or experience working in a health care setting; 2 are veterans. These volunteers are adding to the team at no additional cost. In development is a standardized training program and a method to look at story collection and writing fidelity, which will allow for further expansion of this program.

My Life, My Story continues to expand significantly. A total of 610 veterans have been interviewed, and 348 of these interviews were conducted by volunteers. The project now has 18 active volunteers with 4 more on a waiting list. A pilot has been launched at a WSMMVH outpatient clinic, which interviews VA primary care providers about their life stories and shares them with their veteran patients. There is now collaboration with the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison to offer a 2-week My Story elective to fourth-year medical students in spring 2016. In March 2015, My Life, My Story expanded to 6 pilot facilities across the VA: Asheville, North Carolina; Bronx, New York; Iowa City, Iowa; Reno, Nevada; Topeka, Kansas; and White River Junction, Vermont.

Future Projects

- The team is currently analyzing the themes appearing in veteran stories, using grounded theory methodology

- The process for outpatients is being revised, using phone calls and telehealth modalities to collect stories

- The team members are examining relationships between themes in stories and health/wellness goals identified on the PHI

- Eventually, the team will study how this process might improve the veteran/provider relationship on measures of satisfaction with care, quality of care, and health outcomes. The authors will also assess the effects of this process on provider satisfaction and burnout

Conclusion

Veteran stories, when skillfully elicited and carefully crafted, give providers an opportunity to know their patients better, without impinging on their time. For veterans, the experience of being interviewed and the knowledge that their story will be shared with providers is an important recognition that they matter and have a voice in their health care. In a world of high-technology health care, where time is the only thing in short supply, My Life, My Story leverages the old-world technology of storytelling to bring providers and patients closer together.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Amanda Hall and Jessica Jones who were interviewer/writers on the initial project. Both contributed immeasurably to the design and success of the project. The authors would also like to acknowledge Matt Spira who was our first volunteer interviewer and gave us the inspiration to recruit more volunteers. Volunteer Mary Johnston interviewed and wrote the sample veteran story in this article. We would also like to thank the nursing staff on 4A, 4B, and the community living center for their patience when we were in the way and for their support of the project. Last and most important, we would like to thank the veterans who were interviewed for this project. We have all learned more than we could have imagined from the stories that you shared with us. Your sacrifice, courage, and dedication both in the military and your personal lives are truly an inspiration. Thank you.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Anyone involved with the U.S. health care system has heard one or more of the following dispiriting comments. If you are a patient, you have heard or said, “I wish I felt like my provider understood me. He/she just doesn’t have the time.” If you are a provider, you have heard yourself or another provider say, “I wish I had more time to get to know my patients as people. I could do a better job or at least I could remember them without looking at the chart.” This article describes a novel program—My Life, My Story—instituted at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital (WSMMVH) in Madison, Wisconsin. The program uses personal narratives to foster a sense of connection between providers and their veteran patients.

Related: Infusing Gerontologic Practice Into PACT

My Life, My Story had its origins in a small performance improvement project aimed at helping psychiatric residents learn about their new outpatients during rotation. The clinic staff wanted residents to get to know their patients as people in addition to understanding the veterans’ medical conditions. The veterans were first offered the opportunity to come to writers’ workshops and create personal narratives that would be shared later with their clinicians. Unfortunately, only a few veterans were willing to take on this task.

A more patient-friendly approach for collecting and sharing the stories was developed and funded by the VHA Office of Patient-Centered Care and Cultural Transformation (OPCC&CT). Veterans who chose to participate worked with an interviewer/writer to create a personal narrative, which was then shared with their patient aligned care team (PACT). Another component of the interview process was the Personal Health Inventory (PHI), a questionnaire developed by the OPCC&CT that helps veterans articulate their goals and motivations for physical, social, psychological, and spiritual well-being.1 The PHI and personal narrative were paired, to give health care providers (HCPs) a sense of the veteran and their personal health goals.

Background

The health benefits of telling or writing the story of a difficult emotional event have been demonstrated by Pennebaker.2 In varied groups, from prisoners to patients with chronic pain, the writing or talking about experiences improved mood and lowered distress. In addition, studies of medically ill patients showed a decline in physician visits in the 2 to 6 months following the narrative process.3,4 Improved immune response was also shown for patients with hepatitis B, HIV, asthma, and rheumatoid arthritis in response to completing a narrative.5-7

Related: Experiences of Veterans With Diabetes From Shared Medical Appointments

But the writing task is difficult for many people, especially those with advanced illness. Interviewing these patients and writing their stories is a way to give them a voice that otherwise might go unheard.

Dignity therapy with terminally ill patients, a technique developed by Dr. H.M. Chochinov, used an expert to collect the story by bedside interview and to produce a dignity-enhancing life narrative.8-10 Wise and colleagues modified this process for patients with cancer stages III and IV by using telephone interviews, which showed reduced anger, depression, tension, and an increased sense of peace.11 Personal narratives in which patients tell their story and receive it in written form have been shown to reduce psychological distress, increase hope, and help the patient feel valued.10,12

Pennebaker hypothesized that several mechanisms account for these improvements in health measures.2 First, developing a narrative provides a contextual understanding of stressful events. Creating a personal narrative allows a patient to identify and give meaning to life’s struggles. Through this process, coping is hypothesized to occur.13-15 Second, storytelling connects the teller with a wider audience.16

Another study by Pennebaker and colleagues found an improvement in social connectedness in college students in the days following the disclosure of emotional stories.17 The study speculates that nondisclosure fosters isolation, whereas disclosure connects us with others, helping us to reach out to others and improving a sense of feeling understood.

Methods

Project staff were recruited to conduct the interviews and write the stories. Team members with varied backgrounds and experiences were selected: a nurse at the WSMMVH who served as an army interrogator in Afghanistan; a professional counselor with prior experience working for the VA; and a marriage and family therapist with a poetry MA.

Providers were recruited for participation in the project through (1) presentations to nursing staff on the inpatient units where stories were gathered; (2) compilations of de-identified stories from veterans on those units were distributed; (3) presentations on the project at outpatient clinics, where the narratives of veterans who were patients at those clinics were read aloud; and (4) discussions of the program at monthly hospital-wide meetings.

Related: Diabetes Patient-Centered Medical Home Approach

Patients were recruited from 2 inpatient units and 1 long-term rehabilitative care unit. Interviewers introduced themselves to the veterans, described the project, and gave each one a project brochure. Veterans were given the opportunity to be interviewed immediately, schedule a future interview, decide later, or not participate.

The majority of veterans who participated chose to be interviewed immediately. Scheduling interviews around procedures and discharges on busy inpatient units proved difficult. Overall participation rate was high: 60% of veterans who were told about the project eventually told their story.

Interview Process

Veterans signed a consent form before the interview, and the interviews were recorded on a digital audio recorder. They were informed they could choose to talk—or not talk—about any part of their life, the interviewer would write a draft of the story based on the interview and bring it back for their review, and the story would not be added to their patient record until they gave their approval. Spouses/partners were invited to participate if they desired.

Interviewers were encouraged to follow the lead of the veteran. Those who were clinicians were encouraged to “take off their clinician hat” during the interview. Unless guided otherwise by the veteran, the interview was semichronological and included the following subjects: birth and childhood, family, schooling, military service, relationships and/or marriage, children, career and employment, general health, and current hospital stay and presenting problem.

Interviews lasted about an hour, and 182 interviews were conducted. Interviews were frequently interrupted by HCPs who checked vitals, administering medications, rounding with residents, and so forth. If the HCP indicated that the patient could keep talking, the interview continued. If the patient had to leave the room for a procedure or medical appointment, the interviewer paused the recording and scheduled a time to come back and complete the interview.

After the interview, veterans were told that they could expect to see the first written draft of their story within 2 days. Veterans who were to be discharged the day of the interview or the following day were told that the story would be sent to them in the mail to review at home.

Personal Health Inventory

Interviewers introduced the PHI to veterans as an opportunity to identify their wellness goals and share these with the PACT. Veterans with late-stage cancer or in hospice care were given the option to skip the PHI. Of the 103 veterans who completed the PHI, 96 chose to have the interviewer read the questions and record their answers; only 7 chose to complete the PHI on their own.

One hundred eighty-two veterans completed personal narratives, and 103 completed the PHI. Incomplete PHIs occurred for the following reasons: hospice or end of life, 12; declined, 20; could not complete, 21; discharged, 19; lost to follow-up, 7.

Writing

The quality of the written stories was critical to the success of the project. Creativity was encouraged to produce stories that captured and brought to life the voice and spirit of the interview subject. The team identified the following features of a good story: (1) written in the first person; (2) nonjudgmental; (3) captures the voice of the veteran; (4) accurately reflects the content of the interview; and (5) nondiagnostic (not labeling).

A short story format was used to increase the likelihood that busy providers would read the narratives. Writers were encouraged to limit the length of the stories to 1 to 2 printed pages (650-1,300 words). Completed stories ranged from 95 words to 2,345 words with an average length of 1,053 words. Veterans wrote 3 and the interviewers wrote 178 narratives; 1 narrative was written by a team member who was not present during the interview but listened to the audio recording.

Editing Process

The first draft of the story was printed and given to the veteran to make any desired changes. Veterans reviewed and updated their stories in different ways. Some wrote their changes on the printed copy and had the writer return at a later time to pick it up. Others read through the story with the writer present and wrote their changes on the printed copy. Some had the writer read the story aloud and alerted the writer when an item needed changing.

Drafts were mailed to already discharged veterans, including a postage-paid return envelope to allow them to mail their changes to the team. After incorporating the veteran’s changes, the team member brought back a second draft of the story for the veteran to review. This process was repeated until the veteran gave final approval. Veterans could then approve whether to share their story with their PACT via the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS).

Some participant attrition occurred at this point. Six veterans requested that their stories not go in the CPRS (although 3 of them requested printed copies). One veteran changed his mind after his story was added to the CPRS; the team then immediately removed it. Two veterans died shortly after being released from the hospital and before they could review their stories. The families of both these veterans requested that an audio file of the interview be mailed to them.

Sharing With Family and Providers

Veterans received a printed copy of the approved story and the option to have additional copies for family members. The average number of additional copies requested was 3. Family and friends responded positively to the interview process and stories. Spouses who sat in on the interviews always added something to the interview process, and some were active participants. Eight of the 182 stories were dual narratives that included the words of the veteran and his/her spouse.

Providers were alerted to the personal narratives and PHI via CPRS. The completed story was added to the veteran’s record with the title “My Story.” The story was then electronically cosigned to the veteran’s inpatient and outpatient PACT. Typically, this included 4 people: the inpatient resident and attending physician and the outpatient provider and nurse care manager. If other providers were directly involved in the care of the veteran (mental health, specialists, surgeons), they were also cosigned to the story. If a veteran received primary care outside WSMMVH, their PACT was notified of the presence of the story in CPRS (and given a copy) via encrypted e-mail, in the CPRS “Postings” section.

Program Feedback

The original interviewer/writer team members (2.5 full-time employee equivalent for 6 months) generated 182 stories. The corresponding My Story notes in the CPRS were cosigned to an average of 3.3 providers. The program received both formal (solicited) feedback and informal (unsolicited) feedback from veterans and providers.

After gathering the first 80 stories, the team solicited participant satisfaction data from interviewed veterans, using a 5-point Likert-type scale. Veteran reaction was positive (Figure 1). The team polled VA providers with an online anonymous survey, using the same Likert-type scale to see whether the story and PHI were useful to providers in their clinical practice. The results suggested they were (Figure 2).

Perhaps the most enlightening and touching feedback were the following unsolicited e-mails and comments:

- I have so appreciated these stories, especially because they immediately become a source of connection with the veterans who come in (some for the first time) to see me about their heart failure. In the midst of a heavy “clinical” topic, knowing their stories has helped us form a stronger patient-provider relationship. It has provided moments of levity and a clear way to tell the patient that I am connecting with them and they are important. —VA employee

- I’m a veteran, and I love reading the real stories of veterans, told in their own words. For us, it’s always wonderful to feel like someone is listening. It’s good to feel like someone wants to hear what you’ve traveled through to get where you are. For those of us who put our lives, our health, our relationships, and our honor on the line for so many others, it’s great when someone will just take the time to listen and understand. It most definitely is very healing. —VA employee

- This is a great way to improve provider understanding and decrease bias and eliminate first impression issues, as people are generally ill and cranky when seeking medical care. —Veteran

- The My Story note was wonderful. I truly feel it has helped me to understand my patients better and to know where they are coming from. This is invaluable to the VA where experiences shape our patients in such a profound way. —VA employee

Recent developments at the WSMMVH suggest that veteran stories are becoming an accepted component of clinical care. The heart/lung transplant team requested that the My Story note be part of the transplant workup process for all new patients. The team also found that new HCPs who were assigned to a veteran regularly cosign that veteran’s My Story note to other providers on the care team. In addition, My Story referrals come from all types of HCPs and staff, both within the hospital and at primary care clinics.

Recent Developments

Two WSMMVH employees suggested using volunteers to gather stories and became the first volunteers: One was a housekeeper who had served in the U.S. Army during the Gulf War, and the other was a registered nurse; both had writing experience.

In 2014, staff trained 12 volunteers from the local community who have been trained to interview and write stories. The volunteers have varied professional backgrounds. All have a background and interest in writing or experience working in a health care setting; 2 are veterans. These volunteers are adding to the team at no additional cost. In development is a standardized training program and a method to look at story collection and writing fidelity, which will allow for further expansion of this program.

My Life, My Story continues to expand significantly. A total of 610 veterans have been interviewed, and 348 of these interviews were conducted by volunteers. The project now has 18 active volunteers with 4 more on a waiting list. A pilot has been launched at a WSMMVH outpatient clinic, which interviews VA primary care providers about their life stories and shares them with their veteran patients. There is now collaboration with the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison to offer a 2-week My Story elective to fourth-year medical students in spring 2016. In March 2015, My Life, My Story expanded to 6 pilot facilities across the VA: Asheville, North Carolina; Bronx, New York; Iowa City, Iowa; Reno, Nevada; Topeka, Kansas; and White River Junction, Vermont.

Future Projects

- The team is currently analyzing the themes appearing in veteran stories, using grounded theory methodology

- The process for outpatients is being revised, using phone calls and telehealth modalities to collect stories

- The team members are examining relationships between themes in stories and health/wellness goals identified on the PHI

- Eventually, the team will study how this process might improve the veteran/provider relationship on measures of satisfaction with care, quality of care, and health outcomes. The authors will also assess the effects of this process on provider satisfaction and burnout

Conclusion

Veteran stories, when skillfully elicited and carefully crafted, give providers an opportunity to know their patients better, without impinging on their time. For veterans, the experience of being interviewed and the knowledge that their story will be shared with providers is an important recognition that they matter and have a voice in their health care. In a world of high-technology health care, where time is the only thing in short supply, My Life, My Story leverages the old-world technology of storytelling to bring providers and patients closer together.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Amanda Hall and Jessica Jones who were interviewer/writers on the initial project. Both contributed immeasurably to the design and success of the project. The authors would also like to acknowledge Matt Spira who was our first volunteer interviewer and gave us the inspiration to recruit more volunteers. Volunteer Mary Johnston interviewed and wrote the sample veteran story in this article. We would also like to thank the nursing staff on 4A, 4B, and the community living center for their patience when we were in the way and for their support of the project. Last and most important, we would like to thank the veterans who were interviewed for this project. We have all learned more than we could have imagined from the stories that you shared with us. Your sacrifice, courage, and dedication both in the military and your personal lives are truly an inspiration. Thank you.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Veterans Health Administration, Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation. My Story Personal Health Inventory, Revision 20. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www .va.gov/patientcenteredcare/docs/va-opcc-personal -health-inventory-final-508.pdf. Revised October 7, 2013. Accessed May 11, 2015.

2. Pennebaker JW. Telling stories: the health benefits of narrative. Lit Med. 2000;19(1):3-18.

3. Greenberg MA, Stone AA. Writing about disclosed versus undisclosed traumas: immediate and long term effects on mood and health. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63:75-84.

4. Pennebaker JW, Beall SK. Confronting a traumatic event: toward an understanding of inhibition and disease. J Abnorm Psychol. 1986;95(3):274-281.

5. Petrie KJ, Booth RJ, Pennebaker JW, Davidson KP, Thomas MG. Disclosure of trauma and immune response to hepatitis B vaccination program. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63(5):787-792.

6. Petrie KJ, Fontanilla I, Thomas MG, Booth RJ, Pennebaker JW. Effect of written emotional expression on immune function in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: a randomized trial. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(2):272-275.

7. Smyth JM, Stone AA, Hurewitz A, Kaell A. Effects of writing about stressful experiences on symptom reduction in patients with asthma or rheumatoid arthritis. JAMA. 1999;281(14):1304-1309.

8. Chochinov HM. Dignity-conserving care—a new model for palliative care: helping the patient feel valued. JAMA. 2002;287(17):2253-2260.

9. Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, McClement S, Harlos M. Understanding the will to live in patients near death. Psychosom. 2005;46(1):7-10.

10. Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Breitbart W, et al. Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(8):753-762.

11. Wise M, Marchand L, Roberts LJ, Chih M. Existential suffering in advanced cancer: the buffering effects of narrative: a randomized control trial. Poster presented at: University of Washington School of Medicine 6th Annual Department Fair; April 8, 2015; Seattle, Washington.

12. Hall S, Goddard C, Opio D, Speck PW, Martin P, Higginson IJ. A novel approach to enhancing hope in patients with advanced cancer: a randomised phase II trial of dignity therapy. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2011;1(3):315-321.

13. Heiney SP. The healing power of story. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22(6):899-904.

14. Hyden L-C. Illness and narrative. Soc Health Illness. 1997;19(1):48-69.

15. Carlick A, Biley FC. Thoughts on the therapeutic use of narrative in the promotion of coping in cancer care. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2004;13(4):308-317.

16. Niederhoffer KG, Pennebaker JW. Sharing one’s story: on the benefits of writing or talking about emotional experience. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ, eds. Handbook of Positive Psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001:573-583.

17. Pennebaker JW, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R. Disclosure of traumas and immune function: health implications for psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988:56(2):239-245.

1. Veterans Health Administration, Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation. My Story Personal Health Inventory, Revision 20. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www .va.gov/patientcenteredcare/docs/va-opcc-personal -health-inventory-final-508.pdf. Revised October 7, 2013. Accessed May 11, 2015.

2. Pennebaker JW. Telling stories: the health benefits of narrative. Lit Med. 2000;19(1):3-18.

3. Greenberg MA, Stone AA. Writing about disclosed versus undisclosed traumas: immediate and long term effects on mood and health. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63:75-84.

4. Pennebaker JW, Beall SK. Confronting a traumatic event: toward an understanding of inhibition and disease. J Abnorm Psychol. 1986;95(3):274-281.

5. Petrie KJ, Booth RJ, Pennebaker JW, Davidson KP, Thomas MG. Disclosure of trauma and immune response to hepatitis B vaccination program. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63(5):787-792.

6. Petrie KJ, Fontanilla I, Thomas MG, Booth RJ, Pennebaker JW. Effect of written emotional expression on immune function in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection: a randomized trial. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(2):272-275.

7. Smyth JM, Stone AA, Hurewitz A, Kaell A. Effects of writing about stressful experiences on symptom reduction in patients with asthma or rheumatoid arthritis. JAMA. 1999;281(14):1304-1309.

8. Chochinov HM. Dignity-conserving care—a new model for palliative care: helping the patient feel valued. JAMA. 2002;287(17):2253-2260.

9. Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, McClement S, Harlos M. Understanding the will to live in patients near death. Psychosom. 2005;46(1):7-10.

10. Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Breitbart W, et al. Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(8):753-762.

11. Wise M, Marchand L, Roberts LJ, Chih M. Existential suffering in advanced cancer: the buffering effects of narrative: a randomized control trial. Poster presented at: University of Washington School of Medicine 6th Annual Department Fair; April 8, 2015; Seattle, Washington.

12. Hall S, Goddard C, Opio D, Speck PW, Martin P, Higginson IJ. A novel approach to enhancing hope in patients with advanced cancer: a randomised phase II trial of dignity therapy. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2011;1(3):315-321.

13. Heiney SP. The healing power of story. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1995;22(6):899-904.

14. Hyden L-C. Illness and narrative. Soc Health Illness. 1997;19(1):48-69.

15. Carlick A, Biley FC. Thoughts on the therapeutic use of narrative in the promotion of coping in cancer care. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2004;13(4):308-317.

16. Niederhoffer KG, Pennebaker JW. Sharing one’s story: on the benefits of writing or talking about emotional experience. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ, eds. Handbook of Positive Psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001:573-583.

17. Pennebaker JW, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R. Disclosure of traumas and immune function: health implications for psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988:56(2):239-245.