User login

Painful Nail with Longitudinal Erythronychia

A 46-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to our dermatology clinic with a one year history of progressively increasing pain radiating from the proximal nail fold of her right middle finger. She denied any history of trauma and noted that the pain was worse when her finger was exposed to cold.

On examination, we noted that there was a red line that extended the length of the nail, beginning at the area of pain and ending distally, where the nail split (FIGURE).

FIGURE

Red line extends from area of pain to area of nail splitting

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

Diagnosis: Subungual glomus tumor

Glomus tumor is a rare vascular neoplasm derived from the cells of the glomus body, a specialized arteriovenous shunt involved in temperature regulation. Glomus bodies are most abundant in the extremities, and 75% of glomus tumors are found in the hand.1 The most common location is the subungual region, where glomus bodies are highly concentrated.

These lesions are typically benign, although a malignant variant has been reported in 1% of cases.1,2 Glomus tumors are most common in adults 30 to 50 years of age, with subungual tumors occurring more often in women.3 The majority of glomus tumors are solitary and less than 1 cm in size.2,4 Multiple tumors may be familial and tend to occur in children.2,4

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital practitioners made the correct diagnosis.Patients with subungual glomus tumors present with intense pain that they may describe as shooting or pulsating in nature.

The pain may be spontaneous or triggered by mild trauma or changes in temperature—especially warm to cold. The classic triad of symptoms includes pinpoint tenderness, paroxysmal pain, and cold hypersensitivity. 3,4 The glomus tumor may appear as a focal bluish to erythematous discoloration visible through the nail plate, and in some cases the tumor may form a palpable nodule. Nail deformities such as ridging and distal fissuring occur in approximately one-third of patients.4

Longitudinal erythronychia, as seen in our patient, results when the glomus tumor exerts pressure on the distal nail matrix. This force leads to a thinning of the nail plate and the formation of a groove on the ventral surface of the nail. Swelling of the underlying nail bed with engorgement of vessels produces the red streak that is seen through the thinned nail.5 And, because the affected portion of the nail is fragile, it tends to split distally.

Longitudinal erythronychia with nail dystrophy involving multiple nails is also seen in inflammatory diseases, such as lichen planus and Darier disease, due to multifocal loss of nail matrix function.5

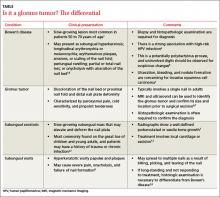

Differential Dx includes subungual warts, Bowen’s disease

Clinical mimics of glomus tumors include neuromas, melanomas, Bowen’s disease, arthritis, gout, paronychia, causalgia, subungual exostosis, osteochondroma, and subungual warts. (The TABLE1,6-8 describes some of the more common mimics.)

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital-based practitioners correctly made the diagnosis.3

Suspect a glomus tumor? Perform these tests

Three clinical tests can aid in evaluating for glomus tumors.

- Love’s test involves applying pressure to the affected fingertip using the head of a pin or the end of a paperclip. The point of maximal tenderness locates the tumor.

- In Hildreth’s test, the physician applies a tourniquet to the digit and repeats the Love’s test. The test is considered suggestive of glomus tumor if the patient no longer experiences tenderness with pressure.

- The cold sensitivity test requires that the physician expose the finger to cold by, say, placing the finger in an ice bath. This exposure will elicit increased pain in a patient who has a glomus tumor.

The sensitivity and specificity of these tests, according to one study involving 18 patients, is as follows: Love’s test (100%, 78%); Hildreth’s test (77.4%, 100%); and the cold sensitivity test (100%, 100%).9 Clinical suspicion must be confirmed by histopathologic examination and the patient must be alerted to the risks of biopsy, which include permanent nail deformity.

In addition, imaging studies may aid in the diagnosis as well as determine the preoperative size and location of the tumor. Radiography may show bone erosion in certain cases, and it is useful in differentiating a glomus tumor from subungual exostosis.10 Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound imaging have also been used to identify glomus tumors and to aid in determining the method of excision.10,11

Surgical excision is the preferred approach

While there are reports of successful treatment with laser and sclerotherapy, surgical excision remains the accepted intervention to relieve pain and minimize recurrence.12,13 The optimal surgical approach, which depends on the location of the tumor,13,14 will minimize the risk of postsurgical nail deformity while allowing for complete tumor removal.

Patients report relief of symptoms following excision, although it may take several weeks for the pain to resolve completely.1 The rate of recurrence following excision is estimated at 10% to 20%.1 This may be due to incomplete excision or the development of a new lesion. Therefore, patients should be re-evaluated and considered for possible re-exploration if symptoms return or persist for more than 3 months after the excision.13

A biopsy for our patient

While the intent of our biopsy was diagnostic, it also proved to be therapeutic as our patient experienced complete resolution of her pain immediately after the procedure. Six months later, she remained asymptomatic and reported no nail deformity. We counseled her on the possibility that her symptoms might return and encouraged her to come back in for further care as needed.

Correspondence

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Wilford Hall Medical Center, Department of Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; thomas.beachkofsky@us.af.mil

1. Baran R, Richert B. Common nail tumors. Dermatol Clin. 206;24:297-311.

2. Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1448-1452.

3. Heys SD, Brittenden J, Atkinson P, et al. Glomus tumour: an analysis of 43 patients and review of the literature. Br J Surg. 1992;79:345-347.

4. McDermott EM, Weiss AP. Glomus tumors. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:1397-1400.

5. De Berker DA, Perrin C, Baran R. Localized longitudinal erythronychia: diagnostic significance and physical explanation. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1253-1257.

6. Grundmeier N, Hamm H, Weissbrich B, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus infection in Bowen’s disease of the nail unit: report of three cases and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2011;223:293-300.

7. Bach DQ, McQueen AA, Lio PA. A refractory wart? Subungual exostosis. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:e3-e4.

8. Garman ME, Orengo IF, Netscher D, et al. On glomus tumors, warts, and razors. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:192-194.

9. Bhaskaranand K, Navadgi BC. Glomus tumour of the hand. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27:229-231.

10. Takemura N, Fujii N, Tanaka T. Subungual glomus tumor diagnosis based on imaging. J Dermatol. 2006;33:389-393.

11. Matsunaga A, Ochiai T, Abe I, et al. Subungual glomus tumour: evaluation of ultrasound imaging in preoperative assessment. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:67-69.

12. Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Friedman PM, Goldberg LH. Long-pulse 595-nm pulsed dye laser for the treatment of a glomus tumor. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1463-1465.

13. Netscher DT, Aburto J, Koepplinger M. Subungual glomus tumor. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:821-823.

14. Takata H, Ikuta Y, Ishida O, et al. Treatment of subungual glomus tumour. Hand Surg. 2001;6:25-27.

A 46-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to our dermatology clinic with a one year history of progressively increasing pain radiating from the proximal nail fold of her right middle finger. She denied any history of trauma and noted that the pain was worse when her finger was exposed to cold.

On examination, we noted that there was a red line that extended the length of the nail, beginning at the area of pain and ending distally, where the nail split (FIGURE).

FIGURE

Red line extends from area of pain to area of nail splitting

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

Diagnosis: Subungual glomus tumor

Glomus tumor is a rare vascular neoplasm derived from the cells of the glomus body, a specialized arteriovenous shunt involved in temperature regulation. Glomus bodies are most abundant in the extremities, and 75% of glomus tumors are found in the hand.1 The most common location is the subungual region, where glomus bodies are highly concentrated.

These lesions are typically benign, although a malignant variant has been reported in 1% of cases.1,2 Glomus tumors are most common in adults 30 to 50 years of age, with subungual tumors occurring more often in women.3 The majority of glomus tumors are solitary and less than 1 cm in size.2,4 Multiple tumors may be familial and tend to occur in children.2,4

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital practitioners made the correct diagnosis.Patients with subungual glomus tumors present with intense pain that they may describe as shooting or pulsating in nature.

The pain may be spontaneous or triggered by mild trauma or changes in temperature—especially warm to cold. The classic triad of symptoms includes pinpoint tenderness, paroxysmal pain, and cold hypersensitivity. 3,4 The glomus tumor may appear as a focal bluish to erythematous discoloration visible through the nail plate, and in some cases the tumor may form a palpable nodule. Nail deformities such as ridging and distal fissuring occur in approximately one-third of patients.4

Longitudinal erythronychia, as seen in our patient, results when the glomus tumor exerts pressure on the distal nail matrix. This force leads to a thinning of the nail plate and the formation of a groove on the ventral surface of the nail. Swelling of the underlying nail bed with engorgement of vessels produces the red streak that is seen through the thinned nail.5 And, because the affected portion of the nail is fragile, it tends to split distally.

Longitudinal erythronychia with nail dystrophy involving multiple nails is also seen in inflammatory diseases, such as lichen planus and Darier disease, due to multifocal loss of nail matrix function.5

Differential Dx includes subungual warts, Bowen’s disease

Clinical mimics of glomus tumors include neuromas, melanomas, Bowen’s disease, arthritis, gout, paronychia, causalgia, subungual exostosis, osteochondroma, and subungual warts. (The TABLE1,6-8 describes some of the more common mimics.)

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital-based practitioners correctly made the diagnosis.3

Suspect a glomus tumor? Perform these tests

Three clinical tests can aid in evaluating for glomus tumors.

- Love’s test involves applying pressure to the affected fingertip using the head of a pin or the end of a paperclip. The point of maximal tenderness locates the tumor.

- In Hildreth’s test, the physician applies a tourniquet to the digit and repeats the Love’s test. The test is considered suggestive of glomus tumor if the patient no longer experiences tenderness with pressure.

- The cold sensitivity test requires that the physician expose the finger to cold by, say, placing the finger in an ice bath. This exposure will elicit increased pain in a patient who has a glomus tumor.

The sensitivity and specificity of these tests, according to one study involving 18 patients, is as follows: Love’s test (100%, 78%); Hildreth’s test (77.4%, 100%); and the cold sensitivity test (100%, 100%).9 Clinical suspicion must be confirmed by histopathologic examination and the patient must be alerted to the risks of biopsy, which include permanent nail deformity.

In addition, imaging studies may aid in the diagnosis as well as determine the preoperative size and location of the tumor. Radiography may show bone erosion in certain cases, and it is useful in differentiating a glomus tumor from subungual exostosis.10 Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound imaging have also been used to identify glomus tumors and to aid in determining the method of excision.10,11

Surgical excision is the preferred approach

While there are reports of successful treatment with laser and sclerotherapy, surgical excision remains the accepted intervention to relieve pain and minimize recurrence.12,13 The optimal surgical approach, which depends on the location of the tumor,13,14 will minimize the risk of postsurgical nail deformity while allowing for complete tumor removal.

Patients report relief of symptoms following excision, although it may take several weeks for the pain to resolve completely.1 The rate of recurrence following excision is estimated at 10% to 20%.1 This may be due to incomplete excision or the development of a new lesion. Therefore, patients should be re-evaluated and considered for possible re-exploration if symptoms return or persist for more than 3 months after the excision.13

A biopsy for our patient

While the intent of our biopsy was diagnostic, it also proved to be therapeutic as our patient experienced complete resolution of her pain immediately after the procedure. Six months later, she remained asymptomatic and reported no nail deformity. We counseled her on the possibility that her symptoms might return and encouraged her to come back in for further care as needed.

Correspondence

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Wilford Hall Medical Center, Department of Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; thomas.beachkofsky@us.af.mil

A 46-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to our dermatology clinic with a one year history of progressively increasing pain radiating from the proximal nail fold of her right middle finger. She denied any history of trauma and noted that the pain was worse when her finger was exposed to cold.

On examination, we noted that there was a red line that extended the length of the nail, beginning at the area of pain and ending distally, where the nail split (FIGURE).

FIGURE

Red line extends from area of pain to area of nail splitting

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

Diagnosis: Subungual glomus tumor

Glomus tumor is a rare vascular neoplasm derived from the cells of the glomus body, a specialized arteriovenous shunt involved in temperature regulation. Glomus bodies are most abundant in the extremities, and 75% of glomus tumors are found in the hand.1 The most common location is the subungual region, where glomus bodies are highly concentrated.

These lesions are typically benign, although a malignant variant has been reported in 1% of cases.1,2 Glomus tumors are most common in adults 30 to 50 years of age, with subungual tumors occurring more often in women.3 The majority of glomus tumors are solitary and less than 1 cm in size.2,4 Multiple tumors may be familial and tend to occur in children.2,4

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital practitioners made the correct diagnosis.Patients with subungual glomus tumors present with intense pain that they may describe as shooting or pulsating in nature.

The pain may be spontaneous or triggered by mild trauma or changes in temperature—especially warm to cold. The classic triad of symptoms includes pinpoint tenderness, paroxysmal pain, and cold hypersensitivity. 3,4 The glomus tumor may appear as a focal bluish to erythematous discoloration visible through the nail plate, and in some cases the tumor may form a palpable nodule. Nail deformities such as ridging and distal fissuring occur in approximately one-third of patients.4

Longitudinal erythronychia, as seen in our patient, results when the glomus tumor exerts pressure on the distal nail matrix. This force leads to a thinning of the nail plate and the formation of a groove on the ventral surface of the nail. Swelling of the underlying nail bed with engorgement of vessels produces the red streak that is seen through the thinned nail.5 And, because the affected portion of the nail is fragile, it tends to split distally.

Longitudinal erythronychia with nail dystrophy involving multiple nails is also seen in inflammatory diseases, such as lichen planus and Darier disease, due to multifocal loss of nail matrix function.5

Differential Dx includes subungual warts, Bowen’s disease

Clinical mimics of glomus tumors include neuromas, melanomas, Bowen’s disease, arthritis, gout, paronychia, causalgia, subungual exostosis, osteochondroma, and subungual warts. (The TABLE1,6-8 describes some of the more common mimics.)

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital-based practitioners correctly made the diagnosis.3

Suspect a glomus tumor? Perform these tests

Three clinical tests can aid in evaluating for glomus tumors.

- Love’s test involves applying pressure to the affected fingertip using the head of a pin or the end of a paperclip. The point of maximal tenderness locates the tumor.

- In Hildreth’s test, the physician applies a tourniquet to the digit and repeats the Love’s test. The test is considered suggestive of glomus tumor if the patient no longer experiences tenderness with pressure.

- The cold sensitivity test requires that the physician expose the finger to cold by, say, placing the finger in an ice bath. This exposure will elicit increased pain in a patient who has a glomus tumor.

The sensitivity and specificity of these tests, according to one study involving 18 patients, is as follows: Love’s test (100%, 78%); Hildreth’s test (77.4%, 100%); and the cold sensitivity test (100%, 100%).9 Clinical suspicion must be confirmed by histopathologic examination and the patient must be alerted to the risks of biopsy, which include permanent nail deformity.

In addition, imaging studies may aid in the diagnosis as well as determine the preoperative size and location of the tumor. Radiography may show bone erosion in certain cases, and it is useful in differentiating a glomus tumor from subungual exostosis.10 Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound imaging have also been used to identify glomus tumors and to aid in determining the method of excision.10,11

Surgical excision is the preferred approach

While there are reports of successful treatment with laser and sclerotherapy, surgical excision remains the accepted intervention to relieve pain and minimize recurrence.12,13 The optimal surgical approach, which depends on the location of the tumor,13,14 will minimize the risk of postsurgical nail deformity while allowing for complete tumor removal.

Patients report relief of symptoms following excision, although it may take several weeks for the pain to resolve completely.1 The rate of recurrence following excision is estimated at 10% to 20%.1 This may be due to incomplete excision or the development of a new lesion. Therefore, patients should be re-evaluated and considered for possible re-exploration if symptoms return or persist for more than 3 months after the excision.13

A biopsy for our patient

While the intent of our biopsy was diagnostic, it also proved to be therapeutic as our patient experienced complete resolution of her pain immediately after the procedure. Six months later, she remained asymptomatic and reported no nail deformity. We counseled her on the possibility that her symptoms might return and encouraged her to come back in for further care as needed.

Correspondence

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Wilford Hall Medical Center, Department of Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; thomas.beachkofsky@us.af.mil

1. Baran R, Richert B. Common nail tumors. Dermatol Clin. 206;24:297-311.

2. Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1448-1452.

3. Heys SD, Brittenden J, Atkinson P, et al. Glomus tumour: an analysis of 43 patients and review of the literature. Br J Surg. 1992;79:345-347.

4. McDermott EM, Weiss AP. Glomus tumors. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:1397-1400.

5. De Berker DA, Perrin C, Baran R. Localized longitudinal erythronychia: diagnostic significance and physical explanation. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1253-1257.

6. Grundmeier N, Hamm H, Weissbrich B, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus infection in Bowen’s disease of the nail unit: report of three cases and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2011;223:293-300.

7. Bach DQ, McQueen AA, Lio PA. A refractory wart? Subungual exostosis. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:e3-e4.

8. Garman ME, Orengo IF, Netscher D, et al. On glomus tumors, warts, and razors. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:192-194.

9. Bhaskaranand K, Navadgi BC. Glomus tumour of the hand. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27:229-231.

10. Takemura N, Fujii N, Tanaka T. Subungual glomus tumor diagnosis based on imaging. J Dermatol. 2006;33:389-393.

11. Matsunaga A, Ochiai T, Abe I, et al. Subungual glomus tumour: evaluation of ultrasound imaging in preoperative assessment. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:67-69.

12. Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Friedman PM, Goldberg LH. Long-pulse 595-nm pulsed dye laser for the treatment of a glomus tumor. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1463-1465.

13. Netscher DT, Aburto J, Koepplinger M. Subungual glomus tumor. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:821-823.

14. Takata H, Ikuta Y, Ishida O, et al. Treatment of subungual glomus tumour. Hand Surg. 2001;6:25-27.

1. Baran R, Richert B. Common nail tumors. Dermatol Clin. 206;24:297-311.

2. Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1448-1452.

3. Heys SD, Brittenden J, Atkinson P, et al. Glomus tumour: an analysis of 43 patients and review of the literature. Br J Surg. 1992;79:345-347.

4. McDermott EM, Weiss AP. Glomus tumors. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:1397-1400.

5. De Berker DA, Perrin C, Baran R. Localized longitudinal erythronychia: diagnostic significance and physical explanation. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1253-1257.

6. Grundmeier N, Hamm H, Weissbrich B, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus infection in Bowen’s disease of the nail unit: report of three cases and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2011;223:293-300.

7. Bach DQ, McQueen AA, Lio PA. A refractory wart? Subungual exostosis. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:e3-e4.

8. Garman ME, Orengo IF, Netscher D, et al. On glomus tumors, warts, and razors. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:192-194.

9. Bhaskaranand K, Navadgi BC. Glomus tumour of the hand. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27:229-231.

10. Takemura N, Fujii N, Tanaka T. Subungual glomus tumor diagnosis based on imaging. J Dermatol. 2006;33:389-393.

11. Matsunaga A, Ochiai T, Abe I, et al. Subungual glomus tumour: evaluation of ultrasound imaging in preoperative assessment. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:67-69.

12. Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Friedman PM, Goldberg LH. Long-pulse 595-nm pulsed dye laser for the treatment of a glomus tumor. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1463-1465.

13. Netscher DT, Aburto J, Koepplinger M. Subungual glomus tumor. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:821-823.

14. Takata H, Ikuta Y, Ishida O, et al. Treatment of subungual glomus tumour. Hand Surg. 2001;6:25-27.

Painful nail with longitudinal erythronychia

A 46-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to our dermatology clinic with a one year history of progressively increasing pain radiating from the proximal nail fold of her right middle finger. She denied any history of trauma and noted that the pain was worse when her finger was exposed to cold.

On examination, we noted that there was a red line that extended the length of the nail, beginning at the area of pain and ending distally, where the nail split (FIGURE).

FIGURE

Red line extends from area of pain to area of nail splitting

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

Diagnosis: Subungual glomus tumor

Glomus tumor is a rare vascular neoplasm derived from the cells of the glomus body, a specialized arteriovenous shunt involved in temperature regulation. Glomus bodies are most abundant in the extremities, and 75% of glomus tumors are found in the hand.1 The most common location is the subungual region, where glomus bodies are highly concentrated.

These lesions are typically benign, although a malignant variant has been reported in 1% of cases.1,2 Glomus tumors are most common in adults 30 to 50 years of age, with subungual tumors occurring more often in women.3 The majority of glomus tumors are solitary and less than 1 cm in size.2,4 Multiple tumors may be familial and tend to occur in children.2,4

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital practitioners made the correct diagnosis.Patients with subungual glomus tumors present with intense pain that they may describe as shooting or pulsating in nature.

The pain may be spontaneous or triggered by mild trauma or changes in temperature—especially warm to cold. The classic triad of symptoms includes pinpoint tenderness, paroxysmal pain, and cold hypersensitivity. 3,4 The glomus tumor may appear as a focal bluish to erythematous discoloration visible through the nail plate, and in some cases the tumor may form a palpable nodule. Nail deformities such as ridging and distal fissuring occur in approximately one-third of patients.4

Longitudinal erythronychia, as seen in our patient, results when the glomus tumor exerts pressure on the distal nail matrix. This force leads to a thinning of the nail plate and the formation of a groove on the ventral surface of the nail. Swelling of the underlying nail bed with engorgement of vessels produces the red streak that is seen through the thinned nail.5 And, because the affected portion of the nail is fragile, it tends to split distally.

Longitudinal erythronychia with nail dystrophy involving multiple nails is also seen in inflammatory diseases, such as lichen planus and Darier disease, due to multifocal loss of nail matrix function.5

Differential Dx includes subungual warts, Bowen’s disease

Clinical mimics of glomus tumors include neuromas, melanomas, Bowen’s disease, arthritis, gout, paronychia, causalgia, subungual exostosis, osteochondroma, and subungual warts. (The TABLE1,6-8 describes some of the more common mimics.)

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital-based practitioners correctly made the diagnosis.3

Suspect a glomus tumor? Perform these tests

Three clinical tests can aid in evaluating for glomus tumors.

- Love’s test involves applying pressure to the affected fingertip using the head of a pin or the end of a paperclip. The point of maximal tenderness locates the tumor.

- In Hildreth’s test, the physician applies a tourniquet to the digit and repeats the Love’s test. The test is considered suggestive of glomus tumor if the patient no longer experiences tenderness with pressure.

- The cold sensitivity test requires that the physician expose the finger to cold by, say, placing the finger in an ice bath. This exposure will elicit increased pain in a patient who has a glomus tumor.

The sensitivity and specificity of these tests, according to one study involving 18 patients, is as follows: Love’s test (100%, 78%); Hildreth’s test (77.4%, 100%); and the cold sensitivity test (100%, 100%).9 Clinical suspicion must be confirmed by histopathologic examination and the patient must be alerted to the risks of biopsy, which include permanent nail deformity.

In addition, imaging studies may aid in the diagnosis as well as determine the preoperative size and location of the tumor. Radiography may show bone erosion in certain cases, and it is useful in differentiating a glomus tumor from subungual exostosis.10 Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound imaging have also been used to identify glomus tumors and to aid in determining the method of excision.10,11

Surgical excision is the preferred approach

While there are reports of successful treatment with laser and sclerotherapy, surgical excision remains the accepted intervention to relieve pain and minimize recurrence.12,13 The optimal surgical approach, which depends on the location of the tumor,13,14 will minimize the risk of postsurgical nail deformity while allowing for complete tumor removal.

A biopsy for our patient

While the intent of our biopsy was diagnostic, it also proved to be therapeutic as our patient experienced complete resolution of her pain immediately after the procedure. Six months later, she remained asymptomatic and reported no nail deformity. We counseled her on the possibility that her symptoms might return and encouraged her to come back in for further care as needed.

Correspondence

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Wilford Hall Medical Center, Department of Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; thomas.beachkofsky@us.af.mil

1. Baran R, Richert B. Common nail tumors. Dermatol Clin. 206;24:297-311.

2. Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1448-1452.

3. Heys SD, Brittenden J, Atkinson P, et al. Glomus tumour: an analysis of 43 patients and review of the literature. Br J Surg. 1992;79:345-347.

4. McDermott EM, Weiss AP. Glomus tumors. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:1397-1400.

5. De Berker DA, Perrin C, Baran R. Localized longitudinal erythronychia: diagnostic significance and physical explanation. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1253-1257.

6. Grundmeier N, Hamm H, Weissbrich B, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus infection in Bowen’s disease of the nail unit: report of three cases and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2011;223:293-300.

7. Bach DQ, McQueen AA, Lio PA. A refractory wart? Subungual exostosis. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:e3-e4.

8. Garman ME, Orengo IF, Netscher D, et al. On glomus tumors, warts, and razors. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:192-194.

9. Bhaskaranand K, Navadgi BC. Glomus tumour of the hand. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27:229-231.

10. Takemura N, Fujii N, Tanaka T. Subungual glomus tumor diagnosis based on imaging. J Dermatol. 2006;33:389-393.

11. Matsunaga A, Ochiai T, Abe I, et al. Subungual glomus tumour: evaluation of ultrasound imaging in preoperative assessment. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:67-69.

12. Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Friedman PM, Goldberg LH. Long-pulse 595-nm pulsed dye laser for the treatment of a glomus tumor. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1463-1465.

13. Netscher DT, Aburto J, Koepplinger M. Subungual glomus tumor. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:821-823.

14. Takata H, Ikuta Y, Ishida O, et al. Treatment of subungual glomus tumour. Hand Surg. 2001;6:25-27.

A 46-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to our dermatology clinic with a one year history of progressively increasing pain radiating from the proximal nail fold of her right middle finger. She denied any history of trauma and noted that the pain was worse when her finger was exposed to cold.

On examination, we noted that there was a red line that extended the length of the nail, beginning at the area of pain and ending distally, where the nail split (FIGURE).

FIGURE

Red line extends from area of pain to area of nail splitting

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

Diagnosis: Subungual glomus tumor

Glomus tumor is a rare vascular neoplasm derived from the cells of the glomus body, a specialized arteriovenous shunt involved in temperature regulation. Glomus bodies are most abundant in the extremities, and 75% of glomus tumors are found in the hand.1 The most common location is the subungual region, where glomus bodies are highly concentrated.

These lesions are typically benign, although a malignant variant has been reported in 1% of cases.1,2 Glomus tumors are most common in adults 30 to 50 years of age, with subungual tumors occurring more often in women.3 The majority of glomus tumors are solitary and less than 1 cm in size.2,4 Multiple tumors may be familial and tend to occur in children.2,4

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital practitioners made the correct diagnosis.Patients with subungual glomus tumors present with intense pain that they may describe as shooting or pulsating in nature.

The pain may be spontaneous or triggered by mild trauma or changes in temperature—especially warm to cold. The classic triad of symptoms includes pinpoint tenderness, paroxysmal pain, and cold hypersensitivity. 3,4 The glomus tumor may appear as a focal bluish to erythematous discoloration visible through the nail plate, and in some cases the tumor may form a palpable nodule. Nail deformities such as ridging and distal fissuring occur in approximately one-third of patients.4

Longitudinal erythronychia, as seen in our patient, results when the glomus tumor exerts pressure on the distal nail matrix. This force leads to a thinning of the nail plate and the formation of a groove on the ventral surface of the nail. Swelling of the underlying nail bed with engorgement of vessels produces the red streak that is seen through the thinned nail.5 And, because the affected portion of the nail is fragile, it tends to split distally.

Longitudinal erythronychia with nail dystrophy involving multiple nails is also seen in inflammatory diseases, such as lichen planus and Darier disease, due to multifocal loss of nail matrix function.5

Differential Dx includes subungual warts, Bowen’s disease

Clinical mimics of glomus tumors include neuromas, melanomas, Bowen’s disease, arthritis, gout, paronychia, causalgia, subungual exostosis, osteochondroma, and subungual warts. (The TABLE1,6-8 describes some of the more common mimics.)

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital-based practitioners correctly made the diagnosis.3

Suspect a glomus tumor? Perform these tests

Three clinical tests can aid in evaluating for glomus tumors.

- Love’s test involves applying pressure to the affected fingertip using the head of a pin or the end of a paperclip. The point of maximal tenderness locates the tumor.

- In Hildreth’s test, the physician applies a tourniquet to the digit and repeats the Love’s test. The test is considered suggestive of glomus tumor if the patient no longer experiences tenderness with pressure.

- The cold sensitivity test requires that the physician expose the finger to cold by, say, placing the finger in an ice bath. This exposure will elicit increased pain in a patient who has a glomus tumor.

The sensitivity and specificity of these tests, according to one study involving 18 patients, is as follows: Love’s test (100%, 78%); Hildreth’s test (77.4%, 100%); and the cold sensitivity test (100%, 100%).9 Clinical suspicion must be confirmed by histopathologic examination and the patient must be alerted to the risks of biopsy, which include permanent nail deformity.

In addition, imaging studies may aid in the diagnosis as well as determine the preoperative size and location of the tumor. Radiography may show bone erosion in certain cases, and it is useful in differentiating a glomus tumor from subungual exostosis.10 Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound imaging have also been used to identify glomus tumors and to aid in determining the method of excision.10,11

Surgical excision is the preferred approach

While there are reports of successful treatment with laser and sclerotherapy, surgical excision remains the accepted intervention to relieve pain and minimize recurrence.12,13 The optimal surgical approach, which depends on the location of the tumor,13,14 will minimize the risk of postsurgical nail deformity while allowing for complete tumor removal.

A biopsy for our patient

While the intent of our biopsy was diagnostic, it also proved to be therapeutic as our patient experienced complete resolution of her pain immediately after the procedure. Six months later, she remained asymptomatic and reported no nail deformity. We counseled her on the possibility that her symptoms might return and encouraged her to come back in for further care as needed.

Correspondence

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Wilford Hall Medical Center, Department of Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; thomas.beachkofsky@us.af.mil

A 46-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to our dermatology clinic with a one year history of progressively increasing pain radiating from the proximal nail fold of her right middle finger. She denied any history of trauma and noted that the pain was worse when her finger was exposed to cold.

On examination, we noted that there was a red line that extended the length of the nail, beginning at the area of pain and ending distally, where the nail split (FIGURE).

FIGURE

Red line extends from area of pain to area of nail splitting

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

Diagnosis: Subungual glomus tumor

Glomus tumor is a rare vascular neoplasm derived from the cells of the glomus body, a specialized arteriovenous shunt involved in temperature regulation. Glomus bodies are most abundant in the extremities, and 75% of glomus tumors are found in the hand.1 The most common location is the subungual region, where glomus bodies are highly concentrated.

These lesions are typically benign, although a malignant variant has been reported in 1% of cases.1,2 Glomus tumors are most common in adults 30 to 50 years of age, with subungual tumors occurring more often in women.3 The majority of glomus tumors are solitary and less than 1 cm in size.2,4 Multiple tumors may be familial and tend to occur in children.2,4

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital practitioners made the correct diagnosis.Patients with subungual glomus tumors present with intense pain that they may describe as shooting or pulsating in nature.

The pain may be spontaneous or triggered by mild trauma or changes in temperature—especially warm to cold. The classic triad of symptoms includes pinpoint tenderness, paroxysmal pain, and cold hypersensitivity. 3,4 The glomus tumor may appear as a focal bluish to erythematous discoloration visible through the nail plate, and in some cases the tumor may form a palpable nodule. Nail deformities such as ridging and distal fissuring occur in approximately one-third of patients.4

Longitudinal erythronychia, as seen in our patient, results when the glomus tumor exerts pressure on the distal nail matrix. This force leads to a thinning of the nail plate and the formation of a groove on the ventral surface of the nail. Swelling of the underlying nail bed with engorgement of vessels produces the red streak that is seen through the thinned nail.5 And, because the affected portion of the nail is fragile, it tends to split distally.

Longitudinal erythronychia with nail dystrophy involving multiple nails is also seen in inflammatory diseases, such as lichen planus and Darier disease, due to multifocal loss of nail matrix function.5

Differential Dx includes subungual warts, Bowen’s disease

Clinical mimics of glomus tumors include neuromas, melanomas, Bowen’s disease, arthritis, gout, paronychia, causalgia, subungual exostosis, osteochondroma, and subungual warts. (The TABLE1,6-8 describes some of the more common mimics.)

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital-based practitioners correctly made the diagnosis.3

Suspect a glomus tumor? Perform these tests

Three clinical tests can aid in evaluating for glomus tumors.

- Love’s test involves applying pressure to the affected fingertip using the head of a pin or the end of a paperclip. The point of maximal tenderness locates the tumor.

- In Hildreth’s test, the physician applies a tourniquet to the digit and repeats the Love’s test. The test is considered suggestive of glomus tumor if the patient no longer experiences tenderness with pressure.

- The cold sensitivity test requires that the physician expose the finger to cold by, say, placing the finger in an ice bath. This exposure will elicit increased pain in a patient who has a glomus tumor.

The sensitivity and specificity of these tests, according to one study involving 18 patients, is as follows: Love’s test (100%, 78%); Hildreth’s test (77.4%, 100%); and the cold sensitivity test (100%, 100%).9 Clinical suspicion must be confirmed by histopathologic examination and the patient must be alerted to the risks of biopsy, which include permanent nail deformity.

In addition, imaging studies may aid in the diagnosis as well as determine the preoperative size and location of the tumor. Radiography may show bone erosion in certain cases, and it is useful in differentiating a glomus tumor from subungual exostosis.10 Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound imaging have also been used to identify glomus tumors and to aid in determining the method of excision.10,11

Surgical excision is the preferred approach

While there are reports of successful treatment with laser and sclerotherapy, surgical excision remains the accepted intervention to relieve pain and minimize recurrence.12,13 The optimal surgical approach, which depends on the location of the tumor,13,14 will minimize the risk of postsurgical nail deformity while allowing for complete tumor removal.

A biopsy for our patient

While the intent of our biopsy was diagnostic, it also proved to be therapeutic as our patient experienced complete resolution of her pain immediately after the procedure. Six months later, she remained asymptomatic and reported no nail deformity. We counseled her on the possibility that her symptoms might return and encouraged her to come back in for further care as needed.

Correspondence

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Wilford Hall Medical Center, Department of Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; thomas.beachkofsky@us.af.mil

1. Baran R, Richert B. Common nail tumors. Dermatol Clin. 206;24:297-311.

2. Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1448-1452.

3. Heys SD, Brittenden J, Atkinson P, et al. Glomus tumour: an analysis of 43 patients and review of the literature. Br J Surg. 1992;79:345-347.

4. McDermott EM, Weiss AP. Glomus tumors. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:1397-1400.

5. De Berker DA, Perrin C, Baran R. Localized longitudinal erythronychia: diagnostic significance and physical explanation. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1253-1257.

6. Grundmeier N, Hamm H, Weissbrich B, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus infection in Bowen’s disease of the nail unit: report of three cases and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2011;223:293-300.

7. Bach DQ, McQueen AA, Lio PA. A refractory wart? Subungual exostosis. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:e3-e4.

8. Garman ME, Orengo IF, Netscher D, et al. On glomus tumors, warts, and razors. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:192-194.

9. Bhaskaranand K, Navadgi BC. Glomus tumour of the hand. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27:229-231.

10. Takemura N, Fujii N, Tanaka T. Subungual glomus tumor diagnosis based on imaging. J Dermatol. 2006;33:389-393.

11. Matsunaga A, Ochiai T, Abe I, et al. Subungual glomus tumour: evaluation of ultrasound imaging in preoperative assessment. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:67-69.

12. Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Friedman PM, Goldberg LH. Long-pulse 595-nm pulsed dye laser for the treatment of a glomus tumor. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1463-1465.

13. Netscher DT, Aburto J, Koepplinger M. Subungual glomus tumor. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:821-823.

14. Takata H, Ikuta Y, Ishida O, et al. Treatment of subungual glomus tumour. Hand Surg. 2001;6:25-27.

1. Baran R, Richert B. Common nail tumors. Dermatol Clin. 206;24:297-311.

2. Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1448-1452.

3. Heys SD, Brittenden J, Atkinson P, et al. Glomus tumour: an analysis of 43 patients and review of the literature. Br J Surg. 1992;79:345-347.

4. McDermott EM, Weiss AP. Glomus tumors. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:1397-1400.

5. De Berker DA, Perrin C, Baran R. Localized longitudinal erythronychia: diagnostic significance and physical explanation. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1253-1257.

6. Grundmeier N, Hamm H, Weissbrich B, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus infection in Bowen’s disease of the nail unit: report of three cases and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2011;223:293-300.

7. Bach DQ, McQueen AA, Lio PA. A refractory wart? Subungual exostosis. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:e3-e4.

8. Garman ME, Orengo IF, Netscher D, et al. On glomus tumors, warts, and razors. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:192-194.

9. Bhaskaranand K, Navadgi BC. Glomus tumour of the hand. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27:229-231.

10. Takemura N, Fujii N, Tanaka T. Subungual glomus tumor diagnosis based on imaging. J Dermatol. 2006;33:389-393.

11. Matsunaga A, Ochiai T, Abe I, et al. Subungual glomus tumour: evaluation of ultrasound imaging in preoperative assessment. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:67-69.

12. Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Friedman PM, Goldberg LH. Long-pulse 595-nm pulsed dye laser for the treatment of a glomus tumor. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1463-1465.

13. Netscher DT, Aburto J, Koepplinger M. Subungual glomus tumor. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:821-823.

14. Takata H, Ikuta Y, Ishida O, et al. Treatment of subungual glomus tumour. Hand Surg. 2001;6:25-27.