User login

Brown Papules on the Penis

The Diagnosis: Bowenoid Papulosis

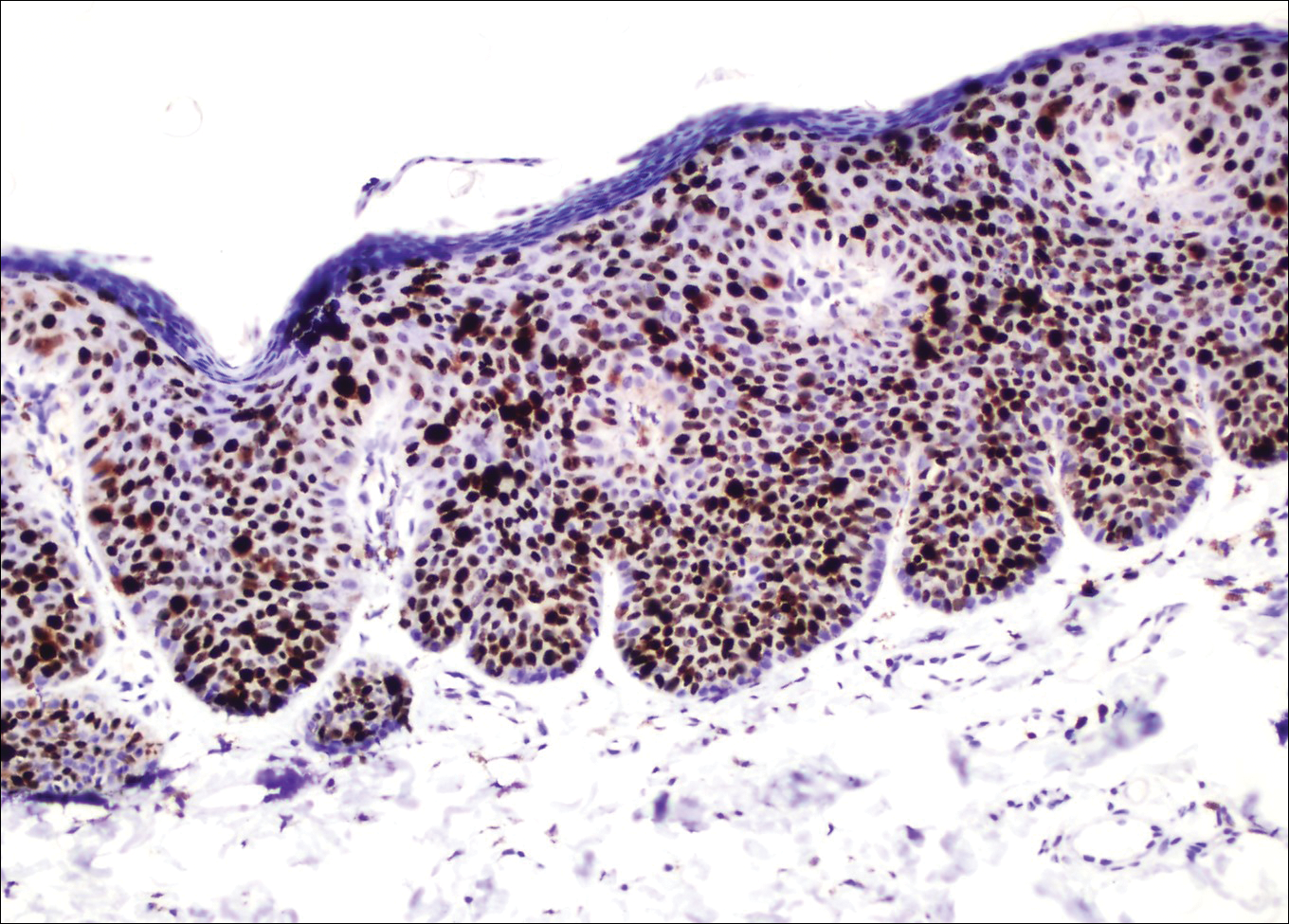

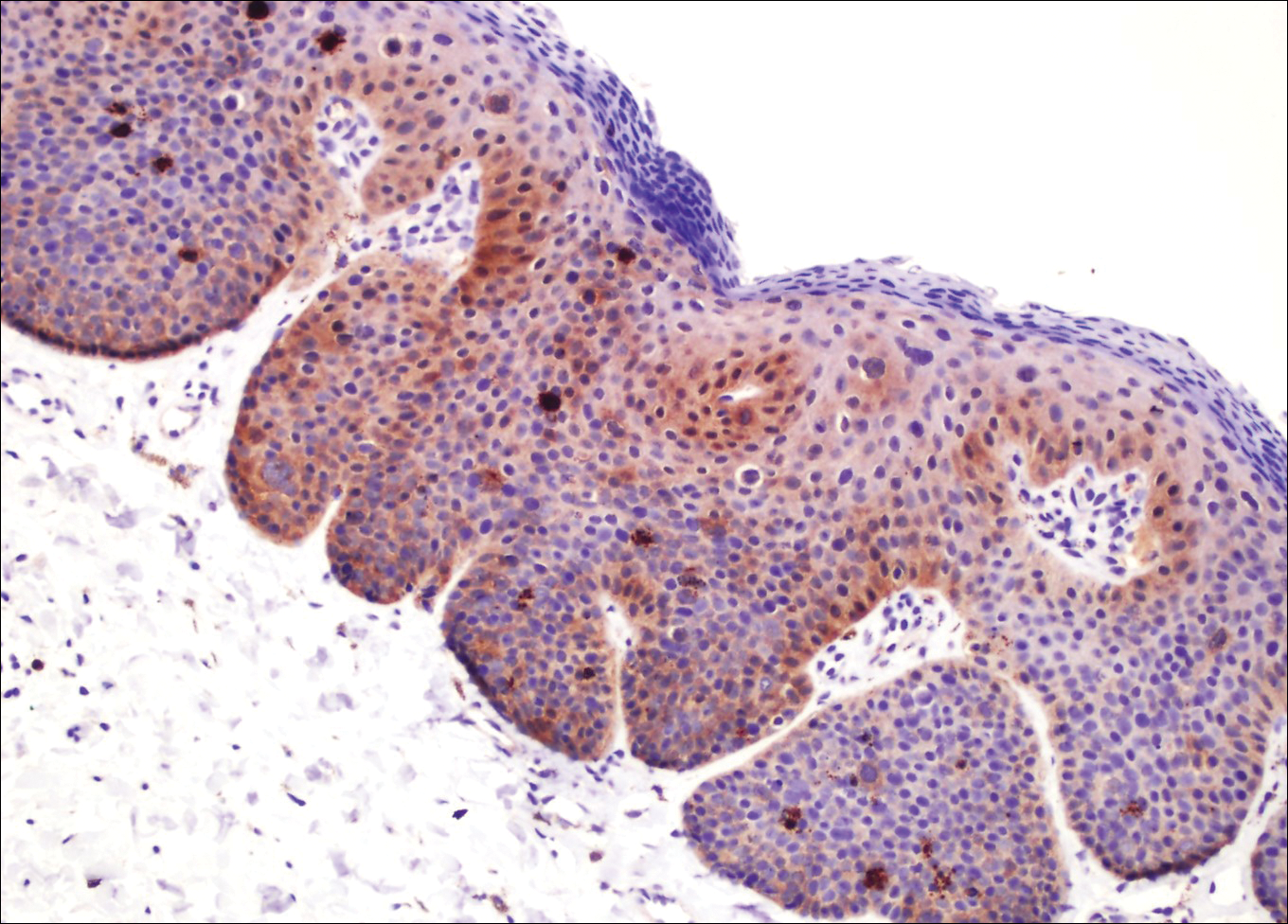

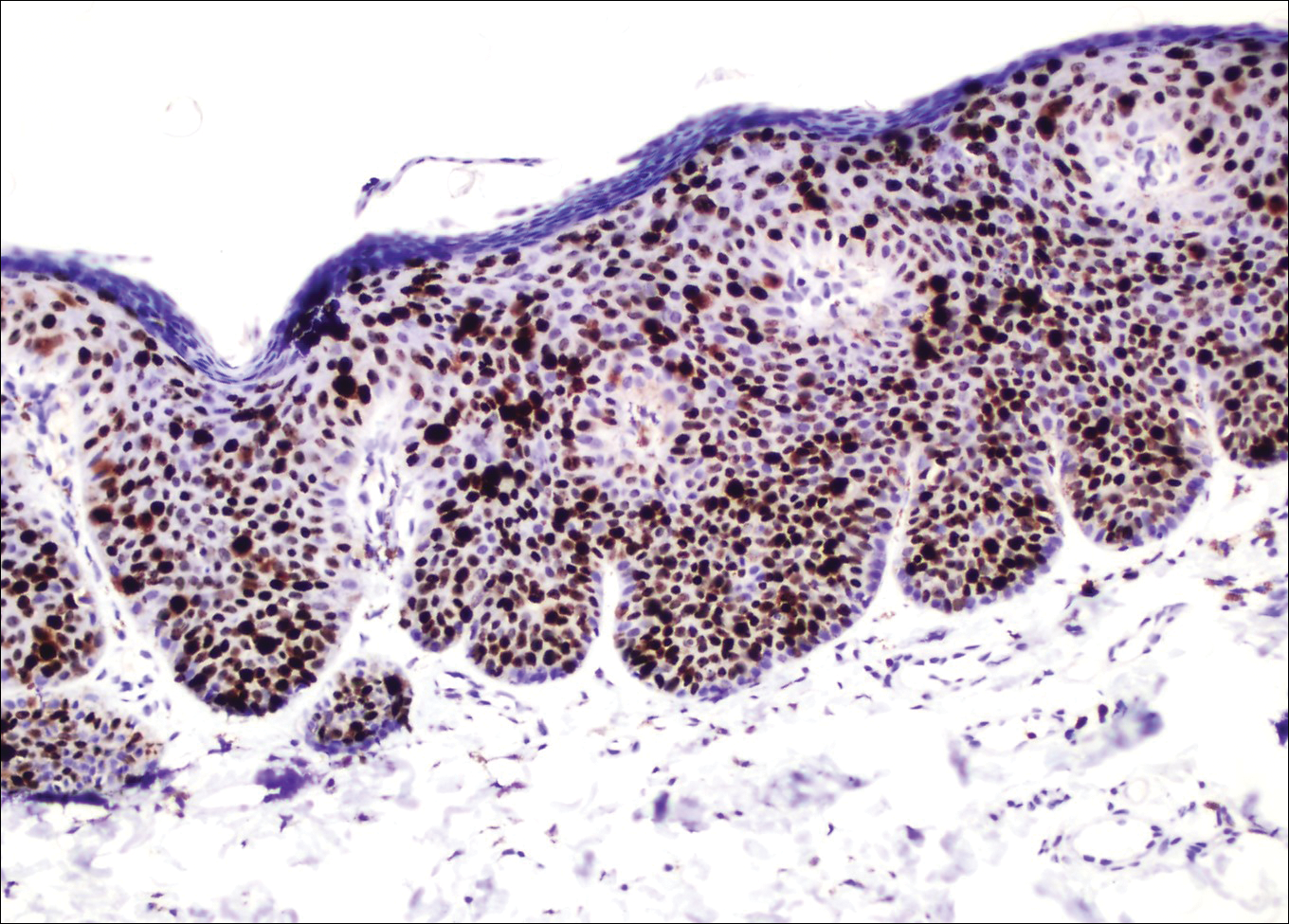

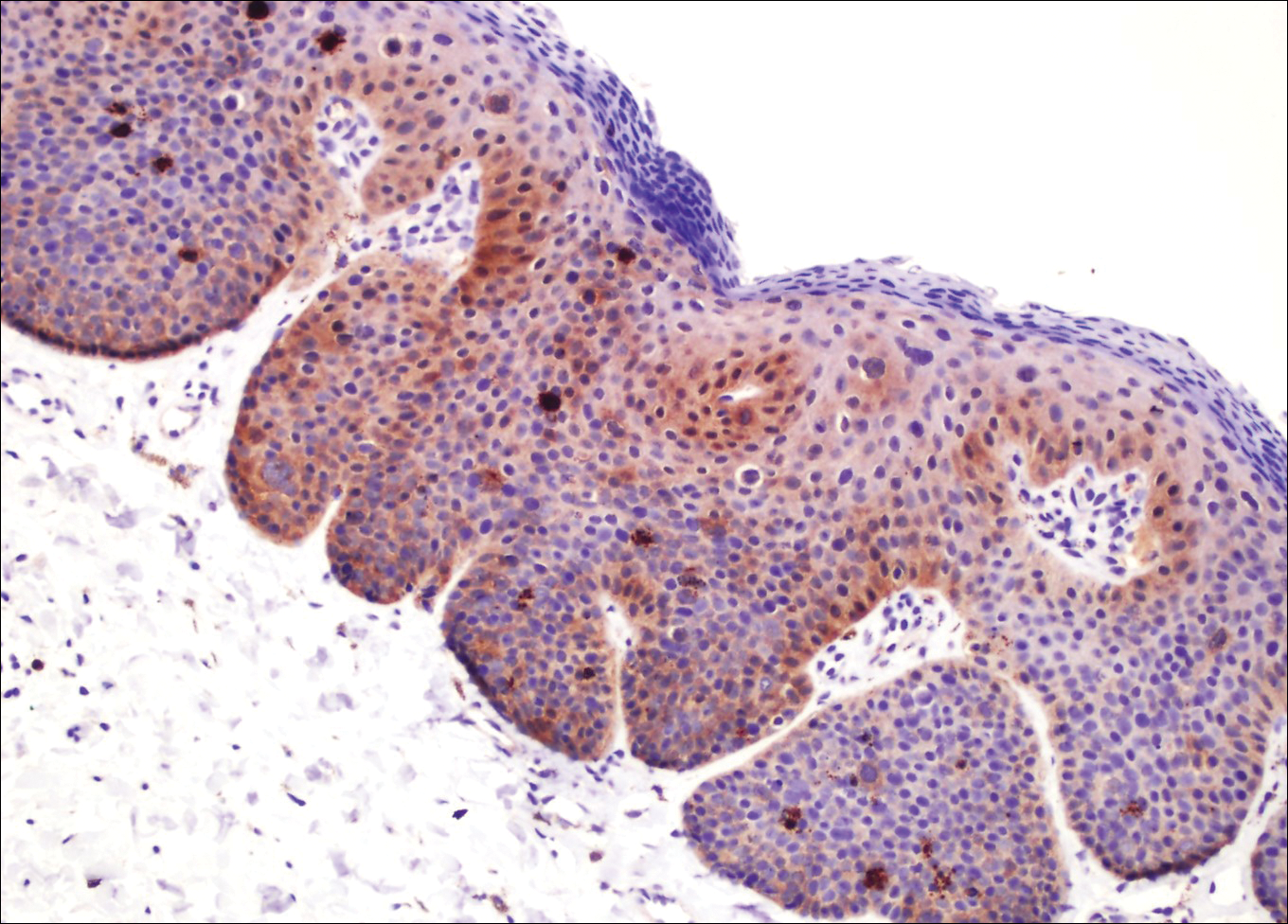

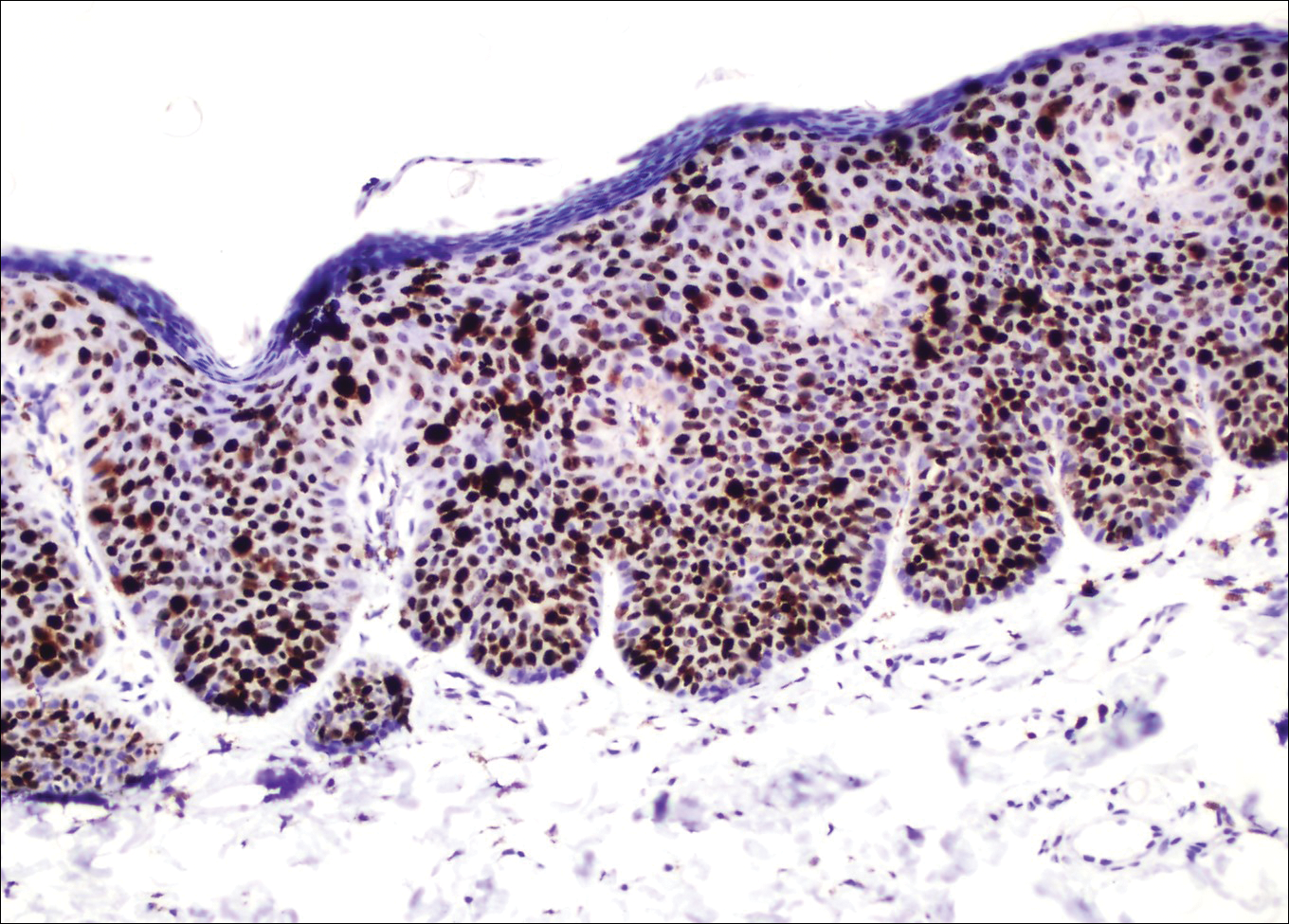

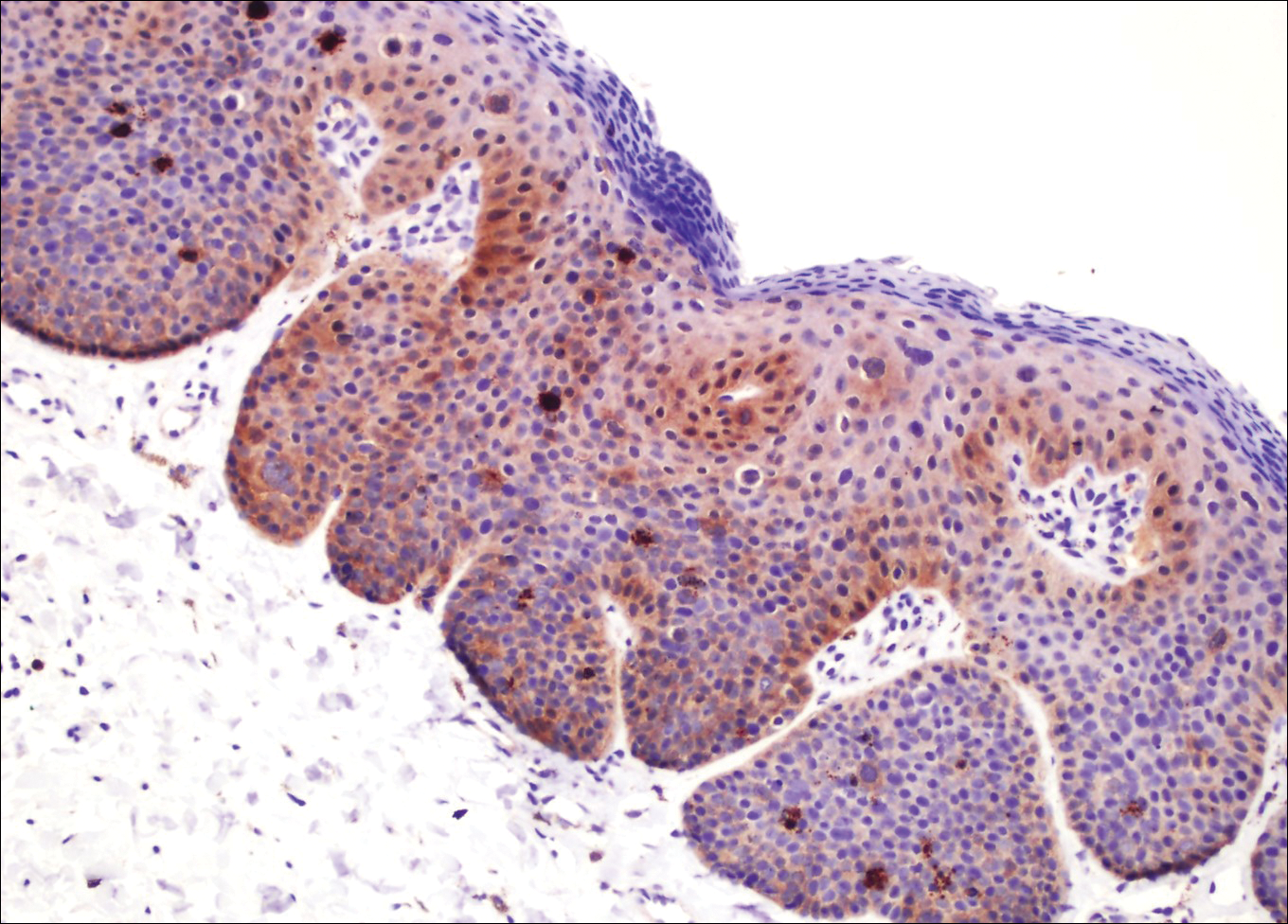

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from the active border of brown plaques on the dorsal penis. Histopathology revealed parakeratotic hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, loss of maturation in epithelium, and full-size atypia (Figure 1). Ki-67 index was 90% positive in the epidermis (Figure 2). Staining for p16 and human papillomavirus (HPV) screening was positive for HPV type 16 (Figure 3). Serologic tests for other sexually transmitted infections were negative. A diagnosis of penile bowenoid papulosis (BP) with grade 3 penile intraepithelial neoplasia was made, and treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) was initiated. Almost total regression was appreciated at 1-month follow-up (Figure 4), and he also was recurrence free at 1-year follow-up.

Penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), or penile squamous cell carcinoma in situ, is a rare disease with high morbidity and mortality rates. Clinically, PIN is comprised of a clinical spectrum including 3 different entities: erythroplasia of Queyrat, Bowen disease, and BP.1 Histologically, PIN also is classified into 3 subtypes according to histological depth of epidermal atypia.1

Bowenoid papulosis usually is characterized by multiple red-brown or flesh-colored papules that most commonly appear on the shaft or glans of the penis. Bowenoid papulosis frequently is associated with high-risk types of HPV, such as HPV type 16, and is sometimes difficult to differentiate clinically from pigmented condyloma acuminatum. The clinical lesions of BP usually are less papillomatous, smoother topped, more polymorphic, and more coalescent compared to common genital viral condyloma acuminatum.2 Bowenoid papulosis usually is seen in young (<30 years of age) sexually active men, unlike the patches or plaques of erythroplasia of Queyrat or Bowen disease, which are seen in older men aged 45 to 75 years. Bowenoid papulosis also has a lower malignancy potential than erythroplasia of Queyrat and Bowen disease.2

Penile melanosis, penile lentigo, and seborrheic keratosis comprise the differential diagnosis of dark spots on the penis and also should be kept in mind. Penile melanosis is the most common cause of dark spots on the penis. When the dark spots have irregular borders and change in color, they may be misdiagnosed as malignant lesions such as melanoma.3 In most cases, biopsy is indicated. Histologically, penile melanosis is characterized by hyperpigmentation of the basal cell layer with no melanocytic hyperplasia. Treatment is unnecessary in most cases.

Penile lentigo presents as small flat pigmented spots on the penile skin with clearly defined margins surrounded by normal-appearing skin. Histologically, it is characterized by hyperplasia of melanocytes above the basement membrane of the epidermis.3

Penile pigmented seborrheic keratosis is a rare clinical entity that can be easily misinterpreted as condyloma acuminatum. Histologically, it is characterized by basal cell hyperplasia with cystic formation in the thickened epidermis. Excisional biopsy may be the only way to rule out malignant disease.

Treatment options for PIN include cryotherapy, CO2 or Nd:YAG lasers, photodynamic therapy, topical 5-FU or imiquimod therapy, and surgical excision such as Mohs micrographic surgery.4-9 Although these therapeutic modalities usually are effective, recurrence is common.6 The patients' discomfort and poor cosmetic and functional outcomes from the surgical removal of lesions also present a challenge in treatment planning.

In our patient, we quickly achieved a good result with topical 5-FU, though the disease was in local advanced stage. It is important for clinicians to consider 5-FU as an effective treatment option for PIN before planning surgery.

- Deen K, Burdon-Jones D. Imiquimod in the treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia: an update. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:86-92.

- Porter WM, Francis N, Hawkins D, et al. Penile intraepithelial neoplasia: clinical spectrum and treatment of 35 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1159-1165.

- Fahmy M. Dermatological disease of the penis. In: Fahmy M. Congenital Anomalies of the Penis. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017:257-264.

- Shimizu A, Kato M, Ishikawa O. Bowenoid papulosis successfully treated with imiquimod 5% cream. J Dermatol. 2014;41:545-546.

- Lucky M, Murthy KV, Rogers B, et al. The treatment of penile carcinoma in situ (CIS) within a UK supra-regional network [published online December 15, 2014]. BJU Int. 2015;115:595-598.

- Alnajjar HM, Lam W, Bolgeri M, et al. Treatment of carcinoma in situ of the glans penis with topical chemotherapy agents. Eur Urol. 2012;62:923-928.

- Wang XL, Wang HW, Guo MX, et al. Combination of immunotherapy and photodynamic therapy in the treatment of bowenoid papulosis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2007;4:88-93.

- Zreik A, Rewhorn M, Vint R, et al. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia [published online December 7, 2016]. Surgeon. 2017;15:321-324.

- Machan M, Brodland D, Zitelli J. Penile squamous cell carcinoma: penis-preserving treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:936-944.

The Diagnosis: Bowenoid Papulosis

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from the active border of brown plaques on the dorsal penis. Histopathology revealed parakeratotic hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, loss of maturation in epithelium, and full-size atypia (Figure 1). Ki-67 index was 90% positive in the epidermis (Figure 2). Staining for p16 and human papillomavirus (HPV) screening was positive for HPV type 16 (Figure 3). Serologic tests for other sexually transmitted infections were negative. A diagnosis of penile bowenoid papulosis (BP) with grade 3 penile intraepithelial neoplasia was made, and treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) was initiated. Almost total regression was appreciated at 1-month follow-up (Figure 4), and he also was recurrence free at 1-year follow-up.

Penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), or penile squamous cell carcinoma in situ, is a rare disease with high morbidity and mortality rates. Clinically, PIN is comprised of a clinical spectrum including 3 different entities: erythroplasia of Queyrat, Bowen disease, and BP.1 Histologically, PIN also is classified into 3 subtypes according to histological depth of epidermal atypia.1

Bowenoid papulosis usually is characterized by multiple red-brown or flesh-colored papules that most commonly appear on the shaft or glans of the penis. Bowenoid papulosis frequently is associated with high-risk types of HPV, such as HPV type 16, and is sometimes difficult to differentiate clinically from pigmented condyloma acuminatum. The clinical lesions of BP usually are less papillomatous, smoother topped, more polymorphic, and more coalescent compared to common genital viral condyloma acuminatum.2 Bowenoid papulosis usually is seen in young (<30 years of age) sexually active men, unlike the patches or plaques of erythroplasia of Queyrat or Bowen disease, which are seen in older men aged 45 to 75 years. Bowenoid papulosis also has a lower malignancy potential than erythroplasia of Queyrat and Bowen disease.2

Penile melanosis, penile lentigo, and seborrheic keratosis comprise the differential diagnosis of dark spots on the penis and also should be kept in mind. Penile melanosis is the most common cause of dark spots on the penis. When the dark spots have irregular borders and change in color, they may be misdiagnosed as malignant lesions such as melanoma.3 In most cases, biopsy is indicated. Histologically, penile melanosis is characterized by hyperpigmentation of the basal cell layer with no melanocytic hyperplasia. Treatment is unnecessary in most cases.

Penile lentigo presents as small flat pigmented spots on the penile skin with clearly defined margins surrounded by normal-appearing skin. Histologically, it is characterized by hyperplasia of melanocytes above the basement membrane of the epidermis.3

Penile pigmented seborrheic keratosis is a rare clinical entity that can be easily misinterpreted as condyloma acuminatum. Histologically, it is characterized by basal cell hyperplasia with cystic formation in the thickened epidermis. Excisional biopsy may be the only way to rule out malignant disease.

Treatment options for PIN include cryotherapy, CO2 or Nd:YAG lasers, photodynamic therapy, topical 5-FU or imiquimod therapy, and surgical excision such as Mohs micrographic surgery.4-9 Although these therapeutic modalities usually are effective, recurrence is common.6 The patients' discomfort and poor cosmetic and functional outcomes from the surgical removal of lesions also present a challenge in treatment planning.

In our patient, we quickly achieved a good result with topical 5-FU, though the disease was in local advanced stage. It is important for clinicians to consider 5-FU as an effective treatment option for PIN before planning surgery.

The Diagnosis: Bowenoid Papulosis

A 4-mm punch biopsy was performed from the active border of brown plaques on the dorsal penis. Histopathology revealed parakeratotic hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, loss of maturation in epithelium, and full-size atypia (Figure 1). Ki-67 index was 90% positive in the epidermis (Figure 2). Staining for p16 and human papillomavirus (HPV) screening was positive for HPV type 16 (Figure 3). Serologic tests for other sexually transmitted infections were negative. A diagnosis of penile bowenoid papulosis (BP) with grade 3 penile intraepithelial neoplasia was made, and treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) was initiated. Almost total regression was appreciated at 1-month follow-up (Figure 4), and he also was recurrence free at 1-year follow-up.

Penile intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), or penile squamous cell carcinoma in situ, is a rare disease with high morbidity and mortality rates. Clinically, PIN is comprised of a clinical spectrum including 3 different entities: erythroplasia of Queyrat, Bowen disease, and BP.1 Histologically, PIN also is classified into 3 subtypes according to histological depth of epidermal atypia.1

Bowenoid papulosis usually is characterized by multiple red-brown or flesh-colored papules that most commonly appear on the shaft or glans of the penis. Bowenoid papulosis frequently is associated with high-risk types of HPV, such as HPV type 16, and is sometimes difficult to differentiate clinically from pigmented condyloma acuminatum. The clinical lesions of BP usually are less papillomatous, smoother topped, more polymorphic, and more coalescent compared to common genital viral condyloma acuminatum.2 Bowenoid papulosis usually is seen in young (<30 years of age) sexually active men, unlike the patches or plaques of erythroplasia of Queyrat or Bowen disease, which are seen in older men aged 45 to 75 years. Bowenoid papulosis also has a lower malignancy potential than erythroplasia of Queyrat and Bowen disease.2

Penile melanosis, penile lentigo, and seborrheic keratosis comprise the differential diagnosis of dark spots on the penis and also should be kept in mind. Penile melanosis is the most common cause of dark spots on the penis. When the dark spots have irregular borders and change in color, they may be misdiagnosed as malignant lesions such as melanoma.3 In most cases, biopsy is indicated. Histologically, penile melanosis is characterized by hyperpigmentation of the basal cell layer with no melanocytic hyperplasia. Treatment is unnecessary in most cases.

Penile lentigo presents as small flat pigmented spots on the penile skin with clearly defined margins surrounded by normal-appearing skin. Histologically, it is characterized by hyperplasia of melanocytes above the basement membrane of the epidermis.3

Penile pigmented seborrheic keratosis is a rare clinical entity that can be easily misinterpreted as condyloma acuminatum. Histologically, it is characterized by basal cell hyperplasia with cystic formation in the thickened epidermis. Excisional biopsy may be the only way to rule out malignant disease.

Treatment options for PIN include cryotherapy, CO2 or Nd:YAG lasers, photodynamic therapy, topical 5-FU or imiquimod therapy, and surgical excision such as Mohs micrographic surgery.4-9 Although these therapeutic modalities usually are effective, recurrence is common.6 The patients' discomfort and poor cosmetic and functional outcomes from the surgical removal of lesions also present a challenge in treatment planning.

In our patient, we quickly achieved a good result with topical 5-FU, though the disease was in local advanced stage. It is important for clinicians to consider 5-FU as an effective treatment option for PIN before planning surgery.

- Deen K, Burdon-Jones D. Imiquimod in the treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia: an update. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:86-92.

- Porter WM, Francis N, Hawkins D, et al. Penile intraepithelial neoplasia: clinical spectrum and treatment of 35 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1159-1165.

- Fahmy M. Dermatological disease of the penis. In: Fahmy M. Congenital Anomalies of the Penis. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017:257-264.

- Shimizu A, Kato M, Ishikawa O. Bowenoid papulosis successfully treated with imiquimod 5% cream. J Dermatol. 2014;41:545-546.

- Lucky M, Murthy KV, Rogers B, et al. The treatment of penile carcinoma in situ (CIS) within a UK supra-regional network [published online December 15, 2014]. BJU Int. 2015;115:595-598.

- Alnajjar HM, Lam W, Bolgeri M, et al. Treatment of carcinoma in situ of the glans penis with topical chemotherapy agents. Eur Urol. 2012;62:923-928.

- Wang XL, Wang HW, Guo MX, et al. Combination of immunotherapy and photodynamic therapy in the treatment of bowenoid papulosis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2007;4:88-93.

- Zreik A, Rewhorn M, Vint R, et al. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia [published online December 7, 2016]. Surgeon. 2017;15:321-324.

- Machan M, Brodland D, Zitelli J. Penile squamous cell carcinoma: penis-preserving treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:936-944.

- Deen K, Burdon-Jones D. Imiquimod in the treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia: an update. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:86-92.

- Porter WM, Francis N, Hawkins D, et al. Penile intraepithelial neoplasia: clinical spectrum and treatment of 35 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:1159-1165.

- Fahmy M. Dermatological disease of the penis. In: Fahmy M. Congenital Anomalies of the Penis. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017:257-264.

- Shimizu A, Kato M, Ishikawa O. Bowenoid papulosis successfully treated with imiquimod 5% cream. J Dermatol. 2014;41:545-546.

- Lucky M, Murthy KV, Rogers B, et al. The treatment of penile carcinoma in situ (CIS) within a UK supra-regional network [published online December 15, 2014]. BJU Int. 2015;115:595-598.

- Alnajjar HM, Lam W, Bolgeri M, et al. Treatment of carcinoma in situ of the glans penis with topical chemotherapy agents. Eur Urol. 2012;62:923-928.

- Wang XL, Wang HW, Guo MX, et al. Combination of immunotherapy and photodynamic therapy in the treatment of bowenoid papulosis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2007;4:88-93.

- Zreik A, Rewhorn M, Vint R, et al. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of penile intraepithelial neoplasia [published online December 7, 2016]. Surgeon. 2017;15:321-324.

- Machan M, Brodland D, Zitelli J. Penile squamous cell carcinoma: penis-preserving treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:936-944.

A 32-year-old man presented to the outpatient clinic with reddish brown lesions on the penis of 5 months' duration. Dermatologic examination revealed multiple mildly infiltrated, bright reddish brown papules and plaques on the dorsal penis.

Severe pruritus • crusted lesions affecting face, extremities, and trunk • hepatitis C virus carrier • Dx?

THE CASE

An 85-year-old woman sought care at our outpatient clinic for a 9-month history of severe pruritus and crusted lesions on her face, extremities, and trunk. She had been diagnosed with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection one year ago and was not taking any medication. The patient, who had been living with her family, had visited various clinics for her complaints and was diagnosed as having contact dermatitis and senile pruritus. She was prescribed topical mometasone furoate and moisturizers.

After 6 months of using this therapy, widespread grey-white plaques and minimal excoriation appeared on her face, scalp, and trunk. This was diagnosed as psoriasis, and the patient was prescribed topical corticosteroids, which she used for 9 months until she came to our clinic. She said the lesions regressed minimally with the topical corticosteroids, but did not fully clear.

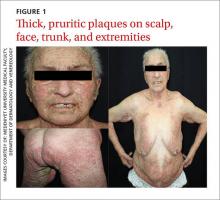

Dermatologic examination revealed widespread erythema and grey-white, cohesive, thick, pruritic plaques on her scalp, face, trunk, and bilateral extremities (FIGURE 1). A punch biopsy specimen was taken from the border of a plaque on her trunk.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A complete blood cell count and wide biochemistry panel, including tumor markers and viral serology for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), were normal. The patient had lymphadenopathy in her posterior cervical, bilateral preauricular, and bilateral inguinal regions.

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and spongiotic edema in the epidermis, and vesiculation and mites in the stratum corneum. The dermal changes consisted of perivascular and diffuse cell infiltrates that were mainly mononuclear cells and eosinophilic granulocytes.

Based on the dermatologic examination and the histopathologic findings, we diagnosed the patient with crusted (Norwegian) scabies.

DISCUSSION

Crusted (Norwegian) scabies is a rare, highly contagious form of scabies that is characterized by the presence of millions of Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis mites in the epidermis.1 This variant of scabies can affect individuals of any age, gender, or race.2 It was first described by Boeck and Danielssen in 1848 in Norway and was named Norwegian scabies by von Hebra in 1862.3 In 2010, more than 200 cases of crusted scabies were reported in the literature.4

Crusted scabies is usually seen in immunocompromised patients, such as the elderly, those who’ve had solid organ transplantation, and those with HIV, malignancy, or malnutrition. Crusted scabies may also occur in patients with decreased sensory function (such as those with leprosy) or decreased ability to scratch, intellectual disabilities, and in those who use biologic agents or systemic/topical corticosteroids.4-8

Crusted scabies is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, especially in children and the elderly, because of complications such as secondary bacterial infections and sepsis.1,3 Widespread inflammation may also cause erythroderma, which can lead to metabolic disorders.

Distinguish it from other pruritic papulosquamous diseases

The differential diagnosis for crusted scabies includes psoriasis, eczema, cutaneous lymphoma, Darier disease, and adverse drug reactions.9 Crusted scabies can be differentiated from these other diagnoses by its clinical presentation and histopathological examination.

Crusted scabies is characterized by hyperkeratosis and wart-like crusts that are due to extreme proliferation of mites in the stratum corneum of the epidermis.2 Lesions are usually localized on acral sites (especially the hands), although the entire body, including the face and the scalp, can be involved.1 Psoriasiform or bullous pemphigoid-like eruptions have also been reported in the literature.5,9

Our patient presented with widespread erythema and psoriasiform grey-white crusts on her scalp, face, chest, periareolar region, and extremities. In addition, she did not have an immunosuppressant disease or medication history.

However, the fact that our patient was using topical corticosteroids for so long explained the extent of her condition. Topical corticosteroids have been linked to scabies incognito.10 Topical or systemic corticosteroid use for long periods of time may alter the skin immune system by suppressing cellular immunity, thereby reducing the inflammatory response. This may lead to progression of the regular variant of scabies to crusted scabies, as our patient had.

Topical treatments, oral ivermectin proven to be effective

Topical keratolytics, permethrin 5%, lindane 1%, crotamiton 10%, sulfur ointment (5%-10%), malathion 0.5%, benzyl benzoate (10%-25%), oral ivermectin (2 doses of 200 mcg/kg/dose), and systemic antihistamines are appropriate therapies.3 While oral ivermectin is effective, it is not available in Turkey.

Because of our patient’s hepatic disorder, we opted for a topical, rather than a systemic, treatment and recommended repeated applications of topical permethrin. Repeated treatment with topical permethrin is often sufficient in patients who are unable to take systemic therapy. In fact, Binic et al4 reported a case in which an elderly patient with crusted scabies (who had previously been treated with systemic and topical corticosteroids) responded well to repeated topical treatment with lindane 1%, 25% benzyl benzoate, and 10% precipitated sulfur.

Our patient. We prescribed topical 5% permethrin lotion for our patient to apply to her entire body 4 times a week and advised her to wash her clothing and bed linens at 140° F. She was scheduled for biweekly check-ups. We also advised the patient’s family to use the same topical therapy 2 times per week because crusted scabies is highly contagious. One month later, our patient’s lesions had resolved (FIGURE 2).

THE TAKEAWAY

Early diagnosis and treatment of crusted scabies is important, both for the treatment of the patient and to stop the spread of the disease. Although rare, crusted scabies should be included in the differential diagnosis of long-term pruritic papulosquamous diseases, and the possibility of an atypical presentation in all patients should be considered—whether their immunity is compromised or not. Scabies should also be considered in patients with a positive family history of the disease and in those with chronic pruritus that is unresponsive to topical therapies.

1. Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG, Morrell DS. Infestations. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, et al, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2012;1423-1426.

2. Subramaniam G, Kaliaperumal K, Duraipandian J, et al. Norwegian scabies in a malnourished young adult: a case report. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2010;4:349-351.

3. Karthikeyan K. Crusted scabies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:340-347.

4. Binic I, Jankovic A, Jovanovic D, et al. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies following systemic and topical corticosteroid therapy. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:188-191.

5. Ramachandran V, Shankar EM, Devaleenal B, et al. Atypically distributed cutaneous lesions of Norwegian scabies in an HIV-positive man in South India: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:82.

6. Lai YC, Teng CJ, Chen PC, et al. Unusual scalp crusted scabies in an adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma patient. Ups J Med Sci. 2011;116:77-78.

7. Saillard C, Darrieux L, Safa G. Crusted scabies complicates etanercept therapy in a patient with severe psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:e138-e139.

8. Marlière V, Roul S, Labrèze C, et al. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies induced by use of topical corticosteroids and treated successfully with ivermectin. J Pediatr. 1999;135:122-124.

9. Goyal NN, Wong GA. Psoriasis or crusted scabies. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:211-212.

10. Kim KJ, Roh KH, Choi JH, et al. Scabies incognito presenting as urticaria pigmentosa in an infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:409-411.

THE CASE

An 85-year-old woman sought care at our outpatient clinic for a 9-month history of severe pruritus and crusted lesions on her face, extremities, and trunk. She had been diagnosed with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection one year ago and was not taking any medication. The patient, who had been living with her family, had visited various clinics for her complaints and was diagnosed as having contact dermatitis and senile pruritus. She was prescribed topical mometasone furoate and moisturizers.

After 6 months of using this therapy, widespread grey-white plaques and minimal excoriation appeared on her face, scalp, and trunk. This was diagnosed as psoriasis, and the patient was prescribed topical corticosteroids, which she used for 9 months until she came to our clinic. She said the lesions regressed minimally with the topical corticosteroids, but did not fully clear.

Dermatologic examination revealed widespread erythema and grey-white, cohesive, thick, pruritic plaques on her scalp, face, trunk, and bilateral extremities (FIGURE 1). A punch biopsy specimen was taken from the border of a plaque on her trunk.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A complete blood cell count and wide biochemistry panel, including tumor markers and viral serology for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), were normal. The patient had lymphadenopathy in her posterior cervical, bilateral preauricular, and bilateral inguinal regions.

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and spongiotic edema in the epidermis, and vesiculation and mites in the stratum corneum. The dermal changes consisted of perivascular and diffuse cell infiltrates that were mainly mononuclear cells and eosinophilic granulocytes.

Based on the dermatologic examination and the histopathologic findings, we diagnosed the patient with crusted (Norwegian) scabies.

DISCUSSION

Crusted (Norwegian) scabies is a rare, highly contagious form of scabies that is characterized by the presence of millions of Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis mites in the epidermis.1 This variant of scabies can affect individuals of any age, gender, or race.2 It was first described by Boeck and Danielssen in 1848 in Norway and was named Norwegian scabies by von Hebra in 1862.3 In 2010, more than 200 cases of crusted scabies were reported in the literature.4

Crusted scabies is usually seen in immunocompromised patients, such as the elderly, those who’ve had solid organ transplantation, and those with HIV, malignancy, or malnutrition. Crusted scabies may also occur in patients with decreased sensory function (such as those with leprosy) or decreased ability to scratch, intellectual disabilities, and in those who use biologic agents or systemic/topical corticosteroids.4-8

Crusted scabies is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, especially in children and the elderly, because of complications such as secondary bacterial infections and sepsis.1,3 Widespread inflammation may also cause erythroderma, which can lead to metabolic disorders.

Distinguish it from other pruritic papulosquamous diseases

The differential diagnosis for crusted scabies includes psoriasis, eczema, cutaneous lymphoma, Darier disease, and adverse drug reactions.9 Crusted scabies can be differentiated from these other diagnoses by its clinical presentation and histopathological examination.

Crusted scabies is characterized by hyperkeratosis and wart-like crusts that are due to extreme proliferation of mites in the stratum corneum of the epidermis.2 Lesions are usually localized on acral sites (especially the hands), although the entire body, including the face and the scalp, can be involved.1 Psoriasiform or bullous pemphigoid-like eruptions have also been reported in the literature.5,9

Our patient presented with widespread erythema and psoriasiform grey-white crusts on her scalp, face, chest, periareolar region, and extremities. In addition, she did not have an immunosuppressant disease or medication history.

However, the fact that our patient was using topical corticosteroids for so long explained the extent of her condition. Topical corticosteroids have been linked to scabies incognito.10 Topical or systemic corticosteroid use for long periods of time may alter the skin immune system by suppressing cellular immunity, thereby reducing the inflammatory response. This may lead to progression of the regular variant of scabies to crusted scabies, as our patient had.

Topical treatments, oral ivermectin proven to be effective

Topical keratolytics, permethrin 5%, lindane 1%, crotamiton 10%, sulfur ointment (5%-10%), malathion 0.5%, benzyl benzoate (10%-25%), oral ivermectin (2 doses of 200 mcg/kg/dose), and systemic antihistamines are appropriate therapies.3 While oral ivermectin is effective, it is not available in Turkey.

Because of our patient’s hepatic disorder, we opted for a topical, rather than a systemic, treatment and recommended repeated applications of topical permethrin. Repeated treatment with topical permethrin is often sufficient in patients who are unable to take systemic therapy. In fact, Binic et al4 reported a case in which an elderly patient with crusted scabies (who had previously been treated with systemic and topical corticosteroids) responded well to repeated topical treatment with lindane 1%, 25% benzyl benzoate, and 10% precipitated sulfur.

Our patient. We prescribed topical 5% permethrin lotion for our patient to apply to her entire body 4 times a week and advised her to wash her clothing and bed linens at 140° F. She was scheduled for biweekly check-ups. We also advised the patient’s family to use the same topical therapy 2 times per week because crusted scabies is highly contagious. One month later, our patient’s lesions had resolved (FIGURE 2).

THE TAKEAWAY

Early diagnosis and treatment of crusted scabies is important, both for the treatment of the patient and to stop the spread of the disease. Although rare, crusted scabies should be included in the differential diagnosis of long-term pruritic papulosquamous diseases, and the possibility of an atypical presentation in all patients should be considered—whether their immunity is compromised or not. Scabies should also be considered in patients with a positive family history of the disease and in those with chronic pruritus that is unresponsive to topical therapies.

THE CASE

An 85-year-old woman sought care at our outpatient clinic for a 9-month history of severe pruritus and crusted lesions on her face, extremities, and trunk. She had been diagnosed with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection one year ago and was not taking any medication. The patient, who had been living with her family, had visited various clinics for her complaints and was diagnosed as having contact dermatitis and senile pruritus. She was prescribed topical mometasone furoate and moisturizers.

After 6 months of using this therapy, widespread grey-white plaques and minimal excoriation appeared on her face, scalp, and trunk. This was diagnosed as psoriasis, and the patient was prescribed topical corticosteroids, which she used for 9 months until she came to our clinic. She said the lesions regressed minimally with the topical corticosteroids, but did not fully clear.

Dermatologic examination revealed widespread erythema and grey-white, cohesive, thick, pruritic plaques on her scalp, face, trunk, and bilateral extremities (FIGURE 1). A punch biopsy specimen was taken from the border of a plaque on her trunk.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A complete blood cell count and wide biochemistry panel, including tumor markers and viral serology for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), were normal. The patient had lymphadenopathy in her posterior cervical, bilateral preauricular, and bilateral inguinal regions.

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and spongiotic edema in the epidermis, and vesiculation and mites in the stratum corneum. The dermal changes consisted of perivascular and diffuse cell infiltrates that were mainly mononuclear cells and eosinophilic granulocytes.

Based on the dermatologic examination and the histopathologic findings, we diagnosed the patient with crusted (Norwegian) scabies.

DISCUSSION

Crusted (Norwegian) scabies is a rare, highly contagious form of scabies that is characterized by the presence of millions of Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis mites in the epidermis.1 This variant of scabies can affect individuals of any age, gender, or race.2 It was first described by Boeck and Danielssen in 1848 in Norway and was named Norwegian scabies by von Hebra in 1862.3 In 2010, more than 200 cases of crusted scabies were reported in the literature.4

Crusted scabies is usually seen in immunocompromised patients, such as the elderly, those who’ve had solid organ transplantation, and those with HIV, malignancy, or malnutrition. Crusted scabies may also occur in patients with decreased sensory function (such as those with leprosy) or decreased ability to scratch, intellectual disabilities, and in those who use biologic agents or systemic/topical corticosteroids.4-8

Crusted scabies is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, especially in children and the elderly, because of complications such as secondary bacterial infections and sepsis.1,3 Widespread inflammation may also cause erythroderma, which can lead to metabolic disorders.

Distinguish it from other pruritic papulosquamous diseases

The differential diagnosis for crusted scabies includes psoriasis, eczema, cutaneous lymphoma, Darier disease, and adverse drug reactions.9 Crusted scabies can be differentiated from these other diagnoses by its clinical presentation and histopathological examination.

Crusted scabies is characterized by hyperkeratosis and wart-like crusts that are due to extreme proliferation of mites in the stratum corneum of the epidermis.2 Lesions are usually localized on acral sites (especially the hands), although the entire body, including the face and the scalp, can be involved.1 Psoriasiform or bullous pemphigoid-like eruptions have also been reported in the literature.5,9

Our patient presented with widespread erythema and psoriasiform grey-white crusts on her scalp, face, chest, periareolar region, and extremities. In addition, she did not have an immunosuppressant disease or medication history.

However, the fact that our patient was using topical corticosteroids for so long explained the extent of her condition. Topical corticosteroids have been linked to scabies incognito.10 Topical or systemic corticosteroid use for long periods of time may alter the skin immune system by suppressing cellular immunity, thereby reducing the inflammatory response. This may lead to progression of the regular variant of scabies to crusted scabies, as our patient had.

Topical treatments, oral ivermectin proven to be effective

Topical keratolytics, permethrin 5%, lindane 1%, crotamiton 10%, sulfur ointment (5%-10%), malathion 0.5%, benzyl benzoate (10%-25%), oral ivermectin (2 doses of 200 mcg/kg/dose), and systemic antihistamines are appropriate therapies.3 While oral ivermectin is effective, it is not available in Turkey.

Because of our patient’s hepatic disorder, we opted for a topical, rather than a systemic, treatment and recommended repeated applications of topical permethrin. Repeated treatment with topical permethrin is often sufficient in patients who are unable to take systemic therapy. In fact, Binic et al4 reported a case in which an elderly patient with crusted scabies (who had previously been treated with systemic and topical corticosteroids) responded well to repeated topical treatment with lindane 1%, 25% benzyl benzoate, and 10% precipitated sulfur.

Our patient. We prescribed topical 5% permethrin lotion for our patient to apply to her entire body 4 times a week and advised her to wash her clothing and bed linens at 140° F. She was scheduled for biweekly check-ups. We also advised the patient’s family to use the same topical therapy 2 times per week because crusted scabies is highly contagious. One month later, our patient’s lesions had resolved (FIGURE 2).

THE TAKEAWAY

Early diagnosis and treatment of crusted scabies is important, both for the treatment of the patient and to stop the spread of the disease. Although rare, crusted scabies should be included in the differential diagnosis of long-term pruritic papulosquamous diseases, and the possibility of an atypical presentation in all patients should be considered—whether their immunity is compromised or not. Scabies should also be considered in patients with a positive family history of the disease and in those with chronic pruritus that is unresponsive to topical therapies.

1. Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG, Morrell DS. Infestations. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, et al, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2012;1423-1426.

2. Subramaniam G, Kaliaperumal K, Duraipandian J, et al. Norwegian scabies in a malnourished young adult: a case report. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2010;4:349-351.

3. Karthikeyan K. Crusted scabies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:340-347.

4. Binic I, Jankovic A, Jovanovic D, et al. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies following systemic and topical corticosteroid therapy. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:188-191.

5. Ramachandran V, Shankar EM, Devaleenal B, et al. Atypically distributed cutaneous lesions of Norwegian scabies in an HIV-positive man in South India: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:82.

6. Lai YC, Teng CJ, Chen PC, et al. Unusual scalp crusted scabies in an adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma patient. Ups J Med Sci. 2011;116:77-78.

7. Saillard C, Darrieux L, Safa G. Crusted scabies complicates etanercept therapy in a patient with severe psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:e138-e139.

8. Marlière V, Roul S, Labrèze C, et al. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies induced by use of topical corticosteroids and treated successfully with ivermectin. J Pediatr. 1999;135:122-124.

9. Goyal NN, Wong GA. Psoriasis or crusted scabies. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:211-212.

10. Kim KJ, Roh KH, Choi JH, et al. Scabies incognito presenting as urticaria pigmentosa in an infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:409-411.

1. Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG, Morrell DS. Infestations. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, et al, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2012;1423-1426.

2. Subramaniam G, Kaliaperumal K, Duraipandian J, et al. Norwegian scabies in a malnourished young adult: a case report. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2010;4:349-351.

3. Karthikeyan K. Crusted scabies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:340-347.

4. Binic I, Jankovic A, Jovanovic D, et al. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies following systemic and topical corticosteroid therapy. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:188-191.

5. Ramachandran V, Shankar EM, Devaleenal B, et al. Atypically distributed cutaneous lesions of Norwegian scabies in an HIV-positive man in South India: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:82.

6. Lai YC, Teng CJ, Chen PC, et al. Unusual scalp crusted scabies in an adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma patient. Ups J Med Sci. 2011;116:77-78.

7. Saillard C, Darrieux L, Safa G. Crusted scabies complicates etanercept therapy in a patient with severe psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:e138-e139.

8. Marlière V, Roul S, Labrèze C, et al. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies induced by use of topical corticosteroids and treated successfully with ivermectin. J Pediatr. 1999;135:122-124.

9. Goyal NN, Wong GA. Psoriasis or crusted scabies. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:211-212.

10. Kim KJ, Roh KH, Choi JH, et al. Scabies incognito presenting as urticaria pigmentosa in an infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:409-411.