User login

Bluish Red Verrucous Lesions on the Leg

The Diagnosis: Linear Verrucous Hemangioma

Verrucous hemangioma is a rare congenital vascular malformation of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues. Although almost invariably present at birth, it may appear later in childhood or even in adulthood. Lesions commonly are found on the legs and may be linear, multiple, and disseminated or sometimes confined to the digits. In the early phase of evolution, the lesions are nonkeratotic, soft, blue-red plaques, but they gradually become increasingly hyperkeratotic.1 Linear verrucous hemangioma is even more rare with few published reports.

In 1937, Halter2 first used the term verrucous hemangioma to describe a 16-year-old adolescent boy who presented with a linear purpuric cluster of plaques extending from the right buttock to the toes. Imperial and Helwig3 later described it as a distinct entity. Since then, similar lesions have been described using a variety of names such as angiokeratoma circumscriptum neviforme, angiokeratoma circumscriptum, angiokeratoma corporis neviforme, keratotic hemangioma, nevus vascularis unius lateralis, and nevus keratoangiomatosus.3 Therefore, the exact incidence is difficult to determine.

Lesions generally are noted at birth or in early childhood and are often located on the lower extremities. The early lesions are bluish red in color. Secondary infection is a frequent complication, resulting in reactive papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis; thus, the older lesions acquire a verrucous or warty surface.3 Clinically, they may resemble angiokeratoma, lym-phangioma circumscriptum, verrucous epidermal nevus, verrucous cancer, or even malignant melanoma. Lesions initially resemble port-wine stains and later may become soft, bluish red vascular swellings that tend to grow in size and become verrucous.1

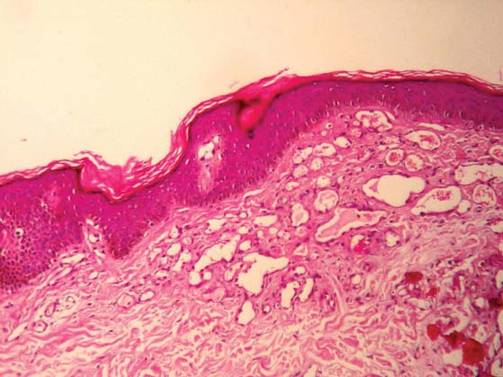

The histologic appearance closely resembles angiokeratoma, as both lesions show vascular spaces beneath a papillomatous and hyperkeratotic epidermis.4 However, in contrast to angiokeratoma, the vascular spaces in verrucous hemangioma also involve the lower dermis and subcutaneous tissues.

Although cases of linear verrucous hemangioma have been reported, its distribution along the lines of Blaschko is rare.5,6 It has been proposed that these lesions may actually be following dermatomal patterns or that the linear arrangement represents genetic mosaicism.5 In our case, the lesion started as a small plaque in childhood and gradually spread linearly to the buttock (Figure 1). A biopsy was taken from the lesion on the right buttock, which showed numerous dilated capillaries in the dermis (Figure 2).

|

Verrucous hemangiomas are best treated by excision. Larger lesions will need grafting. There is a tendency for recurrence to occur unless excision is complete.1 Yang and Ohara7 reported 14 patients with small localized lesions that were cured by 1 session of surgery without recurrence; 9 patients with wider and more extensive lesions required combination therapy in several stages for optimal results.

1. Atherton DJ, Moss C. Naevi and other developmental defects. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. London, England: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 2004:15-60.

2. Halter K. Haemangioma verrucosum mit Osteoatrophie. Dermatol Z. 1937;75:271-279.

3. Imperial R, Helwig EB. Verrucous hemangioma: a clinicopathological study of 21 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:247-253.

4. Calduch L, Ortega C, Navarro V, et al. Verrucous hemangioma: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:213-217.

5. Wentscher U, Happle R. Linear verrucous hemangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:516-518.

6. Jain VK, Aggarwal K, Jain S. Linear verrucous hemangioma on the leg. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:656-658.

7. Yang CH, Ohara K. Successful surgical treatment of verrucous hemangioma: a combined approach. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:913-919.

The Diagnosis: Linear Verrucous Hemangioma

Verrucous hemangioma is a rare congenital vascular malformation of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues. Although almost invariably present at birth, it may appear later in childhood or even in adulthood. Lesions commonly are found on the legs and may be linear, multiple, and disseminated or sometimes confined to the digits. In the early phase of evolution, the lesions are nonkeratotic, soft, blue-red plaques, but they gradually become increasingly hyperkeratotic.1 Linear verrucous hemangioma is even more rare with few published reports.

In 1937, Halter2 first used the term verrucous hemangioma to describe a 16-year-old adolescent boy who presented with a linear purpuric cluster of plaques extending from the right buttock to the toes. Imperial and Helwig3 later described it as a distinct entity. Since then, similar lesions have been described using a variety of names such as angiokeratoma circumscriptum neviforme, angiokeratoma circumscriptum, angiokeratoma corporis neviforme, keratotic hemangioma, nevus vascularis unius lateralis, and nevus keratoangiomatosus.3 Therefore, the exact incidence is difficult to determine.

Lesions generally are noted at birth or in early childhood and are often located on the lower extremities. The early lesions are bluish red in color. Secondary infection is a frequent complication, resulting in reactive papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis; thus, the older lesions acquire a verrucous or warty surface.3 Clinically, they may resemble angiokeratoma, lym-phangioma circumscriptum, verrucous epidermal nevus, verrucous cancer, or even malignant melanoma. Lesions initially resemble port-wine stains and later may become soft, bluish red vascular swellings that tend to grow in size and become verrucous.1

The histologic appearance closely resembles angiokeratoma, as both lesions show vascular spaces beneath a papillomatous and hyperkeratotic epidermis.4 However, in contrast to angiokeratoma, the vascular spaces in verrucous hemangioma also involve the lower dermis and subcutaneous tissues.

Although cases of linear verrucous hemangioma have been reported, its distribution along the lines of Blaschko is rare.5,6 It has been proposed that these lesions may actually be following dermatomal patterns or that the linear arrangement represents genetic mosaicism.5 In our case, the lesion started as a small plaque in childhood and gradually spread linearly to the buttock (Figure 1). A biopsy was taken from the lesion on the right buttock, which showed numerous dilated capillaries in the dermis (Figure 2).

|

Verrucous hemangiomas are best treated by excision. Larger lesions will need grafting. There is a tendency for recurrence to occur unless excision is complete.1 Yang and Ohara7 reported 14 patients with small localized lesions that were cured by 1 session of surgery without recurrence; 9 patients with wider and more extensive lesions required combination therapy in several stages for optimal results.

The Diagnosis: Linear Verrucous Hemangioma

Verrucous hemangioma is a rare congenital vascular malformation of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues. Although almost invariably present at birth, it may appear later in childhood or even in adulthood. Lesions commonly are found on the legs and may be linear, multiple, and disseminated or sometimes confined to the digits. In the early phase of evolution, the lesions are nonkeratotic, soft, blue-red plaques, but they gradually become increasingly hyperkeratotic.1 Linear verrucous hemangioma is even more rare with few published reports.

In 1937, Halter2 first used the term verrucous hemangioma to describe a 16-year-old adolescent boy who presented with a linear purpuric cluster of plaques extending from the right buttock to the toes. Imperial and Helwig3 later described it as a distinct entity. Since then, similar lesions have been described using a variety of names such as angiokeratoma circumscriptum neviforme, angiokeratoma circumscriptum, angiokeratoma corporis neviforme, keratotic hemangioma, nevus vascularis unius lateralis, and nevus keratoangiomatosus.3 Therefore, the exact incidence is difficult to determine.

Lesions generally are noted at birth or in early childhood and are often located on the lower extremities. The early lesions are bluish red in color. Secondary infection is a frequent complication, resulting in reactive papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis; thus, the older lesions acquire a verrucous or warty surface.3 Clinically, they may resemble angiokeratoma, lym-phangioma circumscriptum, verrucous epidermal nevus, verrucous cancer, or even malignant melanoma. Lesions initially resemble port-wine stains and later may become soft, bluish red vascular swellings that tend to grow in size and become verrucous.1

The histologic appearance closely resembles angiokeratoma, as both lesions show vascular spaces beneath a papillomatous and hyperkeratotic epidermis.4 However, in contrast to angiokeratoma, the vascular spaces in verrucous hemangioma also involve the lower dermis and subcutaneous tissues.

Although cases of linear verrucous hemangioma have been reported, its distribution along the lines of Blaschko is rare.5,6 It has been proposed that these lesions may actually be following dermatomal patterns or that the linear arrangement represents genetic mosaicism.5 In our case, the lesion started as a small plaque in childhood and gradually spread linearly to the buttock (Figure 1). A biopsy was taken from the lesion on the right buttock, which showed numerous dilated capillaries in the dermis (Figure 2).

|

Verrucous hemangiomas are best treated by excision. Larger lesions will need grafting. There is a tendency for recurrence to occur unless excision is complete.1 Yang and Ohara7 reported 14 patients with small localized lesions that were cured by 1 session of surgery without recurrence; 9 patients with wider and more extensive lesions required combination therapy in several stages for optimal results.

1. Atherton DJ, Moss C. Naevi and other developmental defects. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. London, England: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 2004:15-60.

2. Halter K. Haemangioma verrucosum mit Osteoatrophie. Dermatol Z. 1937;75:271-279.

3. Imperial R, Helwig EB. Verrucous hemangioma: a clinicopathological study of 21 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:247-253.

4. Calduch L, Ortega C, Navarro V, et al. Verrucous hemangioma: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:213-217.

5. Wentscher U, Happle R. Linear verrucous hemangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:516-518.

6. Jain VK, Aggarwal K, Jain S. Linear verrucous hemangioma on the leg. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:656-658.

7. Yang CH, Ohara K. Successful surgical treatment of verrucous hemangioma: a combined approach. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:913-919.

1. Atherton DJ, Moss C. Naevi and other developmental defects. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 7th ed. London, England: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 2004:15-60.

2. Halter K. Haemangioma verrucosum mit Osteoatrophie. Dermatol Z. 1937;75:271-279.

3. Imperial R, Helwig EB. Verrucous hemangioma: a clinicopathological study of 21 cases. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:247-253.

4. Calduch L, Ortega C, Navarro V, et al. Verrucous hemangioma: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:213-217.

5. Wentscher U, Happle R. Linear verrucous hemangioma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:516-518.

6. Jain VK, Aggarwal K, Jain S. Linear verrucous hemangioma on the leg. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:656-658.

7. Yang CH, Ohara K. Successful surgical treatment of verrucous hemangioma: a combined approach. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:913-919.

An 18-year-old man presented with a history of multiple bluish verrucous lesions over the right leg. A small nodule on the lateral aspect of the right ankle was present at birth; it increased in size and number and gradually extended to the right buttock. He had recurrent bleeding and infection over the lesions. No other remarkable comorbidities were noted. Dermatologic examination revealed multiple well-circumscribed, bluish red, verrucous lesions distributed linearly along the lateral aspect of the leg. The surface of the lesions was verruciform and showed crusting at places. The second and third toes on the right foot were involved. On the buttock, multiple well-defined, bluish red plaques were present. Both limbs were of equal length.

Photoinduced Classic Sweet Syndrome Presenting as Hemorrhagic Bullae

To the Editor:

Sweet syndrome (SS) is characterized by fever; acute onset of painful erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules; peripheral neutrophilic leukocytosis; and histologic findings of a dense neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of primary vasculitis.1 We report a rare case of classic SS presenting with hemorrhagic bullae over photoexposed areas. Our case is notable because of the unusual nature of the clinical manifestation.

A 45-year-old woman presented with painful, fluid-filled lesions on the upper extremities of 1 week’s duration. Lesions were acute in onset and associated with fever. The patient had a history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension, which were well controlled. She also had a history of minimal itching on sun exposure as well as an upper respiratory tract infection 2 months prior to presentation. There was no history of muscle weakness, pain and/or discoloration of the fingertips, or treatment with topical or systemic agents.

On physical examination, the patient was well nourished with an average build. She was febrile (temperature, 38.5°C) with a pulse of 82 beats per minute, a blood pressure of 130/80, and a respiratory rate of 14 breaths per minute. On cutaneous examination multiple erythematous plaques with central large hemorrhagic bullae were present on the extensor aspect of the forearms and dorsum of the left hand. The smallest plaque measured 4×8 cm and the largest measured 8×15 cm (Figure 1). The lesions were tender, and Nikolsky sign was negative. Considering the clinical features, a differential diagnosis of bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, polymorphic light eruption, Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate, and SS were considered. Complete blood cell count demonstrated a hemoglobin level of 12.1 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), total leukocyte count of 13,280/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL), neutrophil count of 80% (reference range, 56%), lymphocyte count of 13% (reference range, 34%), monocyte count of 8% (reference range, 4%), and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 40 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h). Serum creatinine levels were 0.9 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL) and urea nitrogen levels were 26 mg/dL (reference range, 8–23 mg/dL). C-reactive protein was positive, antinuclear antibody was negative, and double-stranded DNA was negative. Ultrasonography of the abdomen and pelvis and a chest radiograph revealed no abnormalities.

Histopathology from a lesion on the forearm revealed a dense, predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate located in the superficial dermis as well as prominent papillary dermal edema infiltration in the dermis with vasodilatation in some areas without leukocytoclastic vasculitis features (Figures 2 and 3). Considering the clinical and histopathologic features, a diagnosis of SS was made, and the patient was started on intravenous dexamethasone (4 mg twice daily) with a dramatic response, as the lesions almost cleared within 4 to 5 days of treatment (Figure 4).

Sweet syndrome was first described in 1964 as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis.2 Sweet syndrome can be subdivided into 3 groups depending on the clinical setting: classic or idiopathic, malignancy associated, and drug induced.3 Classic or idiopathic SS typically affects women in the third to fifth decades of life,4 as seen in our case. The proposed diagnostic criteria for SS state that patients must meet both of the 2 major criteria and 2 of 4 minor criteria for the diagnosis.3 The major criteria include acute onset of typical skin lesions and histopathologic findings consistent with SS. The minor criteria include fever (temperature >38°C) or general malaise; association with malignancy, inflammatory disease, pregnancy, or antecedent respiratory or gastrointestinal tract infection; excellent response to treatment with systemic corticosteroids or potassium iodide; and abnormal laboratory values at presentation (3 of 4 required: erythrocyte sedimentation rate >20 mm/h; leukocyte count >8000/μL; neutrophil count >70%; positive C-reactive protein). Our patient fulfilled both the major criteria and 3 of 4 minor criteria. Although the exact etiology of SS is unknown, it is widely believed that SS may be a hypersensitivity response to underlying bacterial infections such as Yersinia enterocolitica, viral infections, or tumors.5

Cytokine dysregulation also has been indicated in the pathogenesis of SS, an imbalance of cytokine secretion from helper T cells such as IL-2 and IFN-γ, which may stimulate the cytokine cascade leading to activation of neutrophils and release of toxic metabolites.6 The cutaneous manifestations of SS consist of erythematous to violaceous tender papules or nodules that often coalesce to form irregular plaques.7 Rare clinical manifestations include bullous lesions; oral involvement; glomerulonephritis; myositis; and ocular manifestations including conjunctivitis, episcleritis, and iridocyclitis.5,8 Photoaggravated and photoinduced syndromes also have been reported.9

Bullous-type SS has been reported, but all the known cases were secondary to malignancy or were drug induced8,10; they did not present in a classic or idiopathic variant. Our case is unique in that it is a report of the classic SS variant with lesions including bullae over photoexposed areas, possibly indicating a causal association of sun exposure and the development of SS.

The diagnostic histopathologic features of SS include a dense, predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate located in the superficial dermis as well as prominent papillary dermal edema, which occasionally may lead to subepidermal vesiculation.11,12 The epidermis often is normal but spongiosis may be present, and rarely neutrophils may extend into the epidermis to form subcorneal pustules.13 Severe edema in the papillary dermis may cause subepidermal blistering and bullous lesions.10 Systemic steroids are the therapeutic mainstay in SS. Other treatment options include methylprednisolone, potassium iodide, colchicine, indomethacin, cyclosporine, and dapsone.

1. Von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-556.

2. Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;74:349-356.

3. Su WP, Liu HN. Diagnostic criteria for Sweet’s syndrome. Cutis. 1986;37:167-174.

4. Cohen PR. Pregnancy-associated Sweet’s syndrome: world literature review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1993;48:584-587.

5. Cohen PR, Hönigsmann H, Kurzrock R. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome). In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008:289-295.

6. Giasuddin AS, El-Orfi AH, Ziu MM, et al. Sweet’s syndrome: is the pathogenesis mediated by helper T cell type 1 cytokines? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:940-943.

7. Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

8. Lund JJ, Stratman EJ, Jose D, et al. Drug-induced bullous Sweet syndrome with multiple autoimmune features. Autoimmune Dis. 2010;2011:176749.

9. Bessis D, Dereure O, Peyron JL, et al. Photoinduced Sweet syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2003;137:1106-1108.

10. Bielsa S, Baradad M, Martí RM, et al. Sweet’s syndrome with bullous lesions [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2005;96:315-316.

11. Jordaan HF. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: a histopathological study of 37 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 1989;11:99-111.

12. Kemmett D, Hunter JA. Sweet’s syndrome: a clinicopathologic review of twenty-nine cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(3, pt 1):503-507.

13. Wallach D. Neutrophilic disease [in French]. Rev Prat. 1999;49:356-358.

To the Editor:

Sweet syndrome (SS) is characterized by fever; acute onset of painful erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules; peripheral neutrophilic leukocytosis; and histologic findings of a dense neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of primary vasculitis.1 We report a rare case of classic SS presenting with hemorrhagic bullae over photoexposed areas. Our case is notable because of the unusual nature of the clinical manifestation.

A 45-year-old woman presented with painful, fluid-filled lesions on the upper extremities of 1 week’s duration. Lesions were acute in onset and associated with fever. The patient had a history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension, which were well controlled. She also had a history of minimal itching on sun exposure as well as an upper respiratory tract infection 2 months prior to presentation. There was no history of muscle weakness, pain and/or discoloration of the fingertips, or treatment with topical or systemic agents.

On physical examination, the patient was well nourished with an average build. She was febrile (temperature, 38.5°C) with a pulse of 82 beats per minute, a blood pressure of 130/80, and a respiratory rate of 14 breaths per minute. On cutaneous examination multiple erythematous plaques with central large hemorrhagic bullae were present on the extensor aspect of the forearms and dorsum of the left hand. The smallest plaque measured 4×8 cm and the largest measured 8×15 cm (Figure 1). The lesions were tender, and Nikolsky sign was negative. Considering the clinical features, a differential diagnosis of bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, polymorphic light eruption, Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate, and SS were considered. Complete blood cell count demonstrated a hemoglobin level of 12.1 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), total leukocyte count of 13,280/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL), neutrophil count of 80% (reference range, 56%), lymphocyte count of 13% (reference range, 34%), monocyte count of 8% (reference range, 4%), and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 40 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h). Serum creatinine levels were 0.9 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL) and urea nitrogen levels were 26 mg/dL (reference range, 8–23 mg/dL). C-reactive protein was positive, antinuclear antibody was negative, and double-stranded DNA was negative. Ultrasonography of the abdomen and pelvis and a chest radiograph revealed no abnormalities.

Histopathology from a lesion on the forearm revealed a dense, predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate located in the superficial dermis as well as prominent papillary dermal edema infiltration in the dermis with vasodilatation in some areas without leukocytoclastic vasculitis features (Figures 2 and 3). Considering the clinical and histopathologic features, a diagnosis of SS was made, and the patient was started on intravenous dexamethasone (4 mg twice daily) with a dramatic response, as the lesions almost cleared within 4 to 5 days of treatment (Figure 4).

Sweet syndrome was first described in 1964 as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis.2 Sweet syndrome can be subdivided into 3 groups depending on the clinical setting: classic or idiopathic, malignancy associated, and drug induced.3 Classic or idiopathic SS typically affects women in the third to fifth decades of life,4 as seen in our case. The proposed diagnostic criteria for SS state that patients must meet both of the 2 major criteria and 2 of 4 minor criteria for the diagnosis.3 The major criteria include acute onset of typical skin lesions and histopathologic findings consistent with SS. The minor criteria include fever (temperature >38°C) or general malaise; association with malignancy, inflammatory disease, pregnancy, or antecedent respiratory or gastrointestinal tract infection; excellent response to treatment with systemic corticosteroids or potassium iodide; and abnormal laboratory values at presentation (3 of 4 required: erythrocyte sedimentation rate >20 mm/h; leukocyte count >8000/μL; neutrophil count >70%; positive C-reactive protein). Our patient fulfilled both the major criteria and 3 of 4 minor criteria. Although the exact etiology of SS is unknown, it is widely believed that SS may be a hypersensitivity response to underlying bacterial infections such as Yersinia enterocolitica, viral infections, or tumors.5

Cytokine dysregulation also has been indicated in the pathogenesis of SS, an imbalance of cytokine secretion from helper T cells such as IL-2 and IFN-γ, which may stimulate the cytokine cascade leading to activation of neutrophils and release of toxic metabolites.6 The cutaneous manifestations of SS consist of erythematous to violaceous tender papules or nodules that often coalesce to form irregular plaques.7 Rare clinical manifestations include bullous lesions; oral involvement; glomerulonephritis; myositis; and ocular manifestations including conjunctivitis, episcleritis, and iridocyclitis.5,8 Photoaggravated and photoinduced syndromes also have been reported.9

Bullous-type SS has been reported, but all the known cases were secondary to malignancy or were drug induced8,10; they did not present in a classic or idiopathic variant. Our case is unique in that it is a report of the classic SS variant with lesions including bullae over photoexposed areas, possibly indicating a causal association of sun exposure and the development of SS.

The diagnostic histopathologic features of SS include a dense, predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate located in the superficial dermis as well as prominent papillary dermal edema, which occasionally may lead to subepidermal vesiculation.11,12 The epidermis often is normal but spongiosis may be present, and rarely neutrophils may extend into the epidermis to form subcorneal pustules.13 Severe edema in the papillary dermis may cause subepidermal blistering and bullous lesions.10 Systemic steroids are the therapeutic mainstay in SS. Other treatment options include methylprednisolone, potassium iodide, colchicine, indomethacin, cyclosporine, and dapsone.

To the Editor:

Sweet syndrome (SS) is characterized by fever; acute onset of painful erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules; peripheral neutrophilic leukocytosis; and histologic findings of a dense neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of primary vasculitis.1 We report a rare case of classic SS presenting with hemorrhagic bullae over photoexposed areas. Our case is notable because of the unusual nature of the clinical manifestation.

A 45-year-old woman presented with painful, fluid-filled lesions on the upper extremities of 1 week’s duration. Lesions were acute in onset and associated with fever. The patient had a history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension, which were well controlled. She also had a history of minimal itching on sun exposure as well as an upper respiratory tract infection 2 months prior to presentation. There was no history of muscle weakness, pain and/or discoloration of the fingertips, or treatment with topical or systemic agents.

On physical examination, the patient was well nourished with an average build. She was febrile (temperature, 38.5°C) with a pulse of 82 beats per minute, a blood pressure of 130/80, and a respiratory rate of 14 breaths per minute. On cutaneous examination multiple erythematous plaques with central large hemorrhagic bullae were present on the extensor aspect of the forearms and dorsum of the left hand. The smallest plaque measured 4×8 cm and the largest measured 8×15 cm (Figure 1). The lesions were tender, and Nikolsky sign was negative. Considering the clinical features, a differential diagnosis of bullous systemic lupus erythematosus, polymorphic light eruption, Jessner lymphocytic infiltrate, and SS were considered. Complete blood cell count demonstrated a hemoglobin level of 12.1 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), total leukocyte count of 13,280/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL), neutrophil count of 80% (reference range, 56%), lymphocyte count of 13% (reference range, 34%), monocyte count of 8% (reference range, 4%), and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 40 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h). Serum creatinine levels were 0.9 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL) and urea nitrogen levels were 26 mg/dL (reference range, 8–23 mg/dL). C-reactive protein was positive, antinuclear antibody was negative, and double-stranded DNA was negative. Ultrasonography of the abdomen and pelvis and a chest radiograph revealed no abnormalities.

Histopathology from a lesion on the forearm revealed a dense, predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate located in the superficial dermis as well as prominent papillary dermal edema infiltration in the dermis with vasodilatation in some areas without leukocytoclastic vasculitis features (Figures 2 and 3). Considering the clinical and histopathologic features, a diagnosis of SS was made, and the patient was started on intravenous dexamethasone (4 mg twice daily) with a dramatic response, as the lesions almost cleared within 4 to 5 days of treatment (Figure 4).

Sweet syndrome was first described in 1964 as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis.2 Sweet syndrome can be subdivided into 3 groups depending on the clinical setting: classic or idiopathic, malignancy associated, and drug induced.3 Classic or idiopathic SS typically affects women in the third to fifth decades of life,4 as seen in our case. The proposed diagnostic criteria for SS state that patients must meet both of the 2 major criteria and 2 of 4 minor criteria for the diagnosis.3 The major criteria include acute onset of typical skin lesions and histopathologic findings consistent with SS. The minor criteria include fever (temperature >38°C) or general malaise; association with malignancy, inflammatory disease, pregnancy, or antecedent respiratory or gastrointestinal tract infection; excellent response to treatment with systemic corticosteroids or potassium iodide; and abnormal laboratory values at presentation (3 of 4 required: erythrocyte sedimentation rate >20 mm/h; leukocyte count >8000/μL; neutrophil count >70%; positive C-reactive protein). Our patient fulfilled both the major criteria and 3 of 4 minor criteria. Although the exact etiology of SS is unknown, it is widely believed that SS may be a hypersensitivity response to underlying bacterial infections such as Yersinia enterocolitica, viral infections, or tumors.5

Cytokine dysregulation also has been indicated in the pathogenesis of SS, an imbalance of cytokine secretion from helper T cells such as IL-2 and IFN-γ, which may stimulate the cytokine cascade leading to activation of neutrophils and release of toxic metabolites.6 The cutaneous manifestations of SS consist of erythematous to violaceous tender papules or nodules that often coalesce to form irregular plaques.7 Rare clinical manifestations include bullous lesions; oral involvement; glomerulonephritis; myositis; and ocular manifestations including conjunctivitis, episcleritis, and iridocyclitis.5,8 Photoaggravated and photoinduced syndromes also have been reported.9

Bullous-type SS has been reported, but all the known cases were secondary to malignancy or were drug induced8,10; they did not present in a classic or idiopathic variant. Our case is unique in that it is a report of the classic SS variant with lesions including bullae over photoexposed areas, possibly indicating a causal association of sun exposure and the development of SS.

The diagnostic histopathologic features of SS include a dense, predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate located in the superficial dermis as well as prominent papillary dermal edema, which occasionally may lead to subepidermal vesiculation.11,12 The epidermis often is normal but spongiosis may be present, and rarely neutrophils may extend into the epidermis to form subcorneal pustules.13 Severe edema in the papillary dermis may cause subepidermal blistering and bullous lesions.10 Systemic steroids are the therapeutic mainstay in SS. Other treatment options include methylprednisolone, potassium iodide, colchicine, indomethacin, cyclosporine, and dapsone.

1. Von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-556.

2. Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;74:349-356.

3. Su WP, Liu HN. Diagnostic criteria for Sweet’s syndrome. Cutis. 1986;37:167-174.

4. Cohen PR. Pregnancy-associated Sweet’s syndrome: world literature review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1993;48:584-587.

5. Cohen PR, Hönigsmann H, Kurzrock R. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome). In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008:289-295.

6. Giasuddin AS, El-Orfi AH, Ziu MM, et al. Sweet’s syndrome: is the pathogenesis mediated by helper T cell type 1 cytokines? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:940-943.

7. Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

8. Lund JJ, Stratman EJ, Jose D, et al. Drug-induced bullous Sweet syndrome with multiple autoimmune features. Autoimmune Dis. 2010;2011:176749.

9. Bessis D, Dereure O, Peyron JL, et al. Photoinduced Sweet syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2003;137:1106-1108.

10. Bielsa S, Baradad M, Martí RM, et al. Sweet’s syndrome with bullous lesions [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2005;96:315-316.

11. Jordaan HF. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: a histopathological study of 37 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 1989;11:99-111.

12. Kemmett D, Hunter JA. Sweet’s syndrome: a clinicopathologic review of twenty-nine cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(3, pt 1):503-507.

13. Wallach D. Neutrophilic disease [in French]. Rev Prat. 1999;49:356-358.

1. Von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-556.

2. Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;74:349-356.

3. Su WP, Liu HN. Diagnostic criteria for Sweet’s syndrome. Cutis. 1986;37:167-174.

4. Cohen PR. Pregnancy-associated Sweet’s syndrome: world literature review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1993;48:584-587.

5. Cohen PR, Hönigsmann H, Kurzrock R. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome). In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2008:289-295.

6. Giasuddin AS, El-Orfi AH, Ziu MM, et al. Sweet’s syndrome: is the pathogenesis mediated by helper T cell type 1 cytokines? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:940-943.

7. Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34.

8. Lund JJ, Stratman EJ, Jose D, et al. Drug-induced bullous Sweet syndrome with multiple autoimmune features. Autoimmune Dis. 2010;2011:176749.

9. Bessis D, Dereure O, Peyron JL, et al. Photoinduced Sweet syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2003;137:1106-1108.

10. Bielsa S, Baradad M, Martí RM, et al. Sweet’s syndrome with bullous lesions [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2005;96:315-316.

11. Jordaan HF. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: a histopathological study of 37 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 1989;11:99-111.

12. Kemmett D, Hunter JA. Sweet’s syndrome: a clinicopathologic review of twenty-nine cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(3, pt 1):503-507.

13. Wallach D. Neutrophilic disease [in French]. Rev Prat. 1999;49:356-358.