User login

New Moves

The transition from hospital to home or to another care site is a high-risk period for the patient for a number of reasons, as we have discussed in The Hospitalist this year. Ineffective communication with the patient and between healthcare practitioners at discharge is common. In addition, primary care providers increasingly delegate inpatient care to hospitalists. This delegation of care can lead to gaps in knowledge that present risks to patient safety.

Further, information transfer among healthcare practitioners—whether they be primary care providers or hospitalists—and their patients is often compromised by record inaccuracies, omissions, illegibility, information never delivered, and delays in generation or transmission.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has identified recall error, increased clinician workloads, interface failures between physicians and clerical staff, and inadequate training of physicians to respect the discharge process as the root causes of deficiencies in the current process of information transfer at discharge. While an interoperable health information technology infrastructure for the nation could effectively address many issues related to discharge planning, such a solution is certainly many years away.

New Approaches

Given the fact that a nationwide, interoperable health information technology infrastructure is not yet a reality, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) is exploring multiple approaches for improving communication with patients and among practitioners in the discharge planning process. This article details those strategies and is meant to stimulate discussion and elicit suggestions for future approaches.

If you have any suggestions for improving the discharge planning process, e-mail us at ldionne@wiley.com. We’ll publish the most effective and intriguing responses in a future issue of The Hospitalist.

Discharge Planning Standards

Patients may be discharged from the hospital entirely or transferred to another level of care, treatment, and services; they may be reassigned to different professionals or settings for continued services. JCAHO standards require that the hospital’s processes for transfer or discharge be based on the patient’s assessed needs. To facilitate discharge or transfer, the hospital should assess the patient’s needs, plan for discharge or transfer, facilitate the discharge or transfer process, and help to ensure that continuity of care, treatment, and services is maintained.

These standards (found in the Provision of Care (PC), Ethics, Rights and Responsibilities (RI), and Management of Information (IM) chapters of the hospital accreditation manual) will be updated in July 2007. The changes include both new language and new requirements meant to improve communication with patients and among providers during the discharge planning process. Rather than a significant overhaul, these changes can be viewed as refinements to the existing standards that will help hospitals ensure that the intent of each standard is actually carried out to benefit patients. For example, an element of performance for standard PC.4.10 that addresses development of a plan of care now specifies that this process should be individualized to the patient’s needs. Another example is standard IM.6.20, for which an element of performance will require that the medical record contain medications dispensed or prescribed at discharge.

It is also important to note that JCAHO standards underscore the importance of the patient retaining information. Today, JCAHO requires—through its National Patient Safety Goals—that a list of current medications be provided to the patient at discharge. For patients who have been treated by a hospitalist, this requirement is especially important when they return to their primary care physicians for follow-up treatment.

Discharge Planning During the On-Site Survey

JCAHO began more closely examining discharge planning in 2005 by piloting a new process that surveyors used to evaluate standards compliance in 2006. The first option tested is a concurrent review in which surveyors observe the discharge instructions as they are being taught to the patient and then interview the patient about the content. The second option is a retrospective review and entails calling patients 24 to 48 hours after discharge to ascertain their understanding of the medication regimen and other instructions provided. Both options are used by JCAHO surveyors to understand how practitioners, nurses, and other caregivers carry out the hospital’s policies.

To help hospitalists understand how surveyors approach this process, the following summary provides information about the two review options.

Discharge Planning—Active Review

- Ask for a list of patients who will be discharged during the survey.

- Review the patient’s medical/clinical record for discharge orders.

- Request that the organization obtain patient permission to observe the discharge process.

- Observe the clinician providing discharge instructions. Components of the discharge instruction may include:

- Activity;

- Diet;

- Medications (post-discharge);

- Plans for physician follow-up;

- Wound care, if applicable;

- Signs and symptoms to be aware of (i.e., elevated temperature, medication side effects);

- The name and telephone number of a physician to call should a problem or question arise following discharge; and

- Patient repetition of information to confirm understanding.

- Review the written discharge instructions given to the patient. The discharge instructions are written in a language the patient can read and understand.

- Interview the patient to determine the patient’s level of understanding of discharge instructions. If applicable to the instructions given to the patient being observed, the patient should understand:

- The purpose for taking any new medication;

- How to take the medication, including dose and frequency;

- Possible side effects of medication;

- The medication regimen, including continuation or discontinuation of medications taken prior to hospital admission;

- Contraindications between prescribed medications and over-the-counter medications and herbal remedies;

- Changes in diet and dietary restric- tions or supplements;

- Signs and symptoms of potential problems and who to call with questions and concerns;

- Information regarding continued self-care (i.e., wound care, activity);

- Follow-up process with physician(s); and

- Arrangements made for home-health needs (i.e., oxygen therapy, physical therapy).

- Interview the nurse/clinician to ascertain the origination of discharge information (physician-nurse communication regarding discharge instruction).

Discharge Planning—Retrospective Review

- Ask for a list of patients discharged during the past 48 hours.

- Review the patient’s old medical record for discharge orders.

- Request that the organization stay with the surveyor as phone calls are made. The organization should first talk with the patient to explain the purpose of the call and obtain permission for a phone interview.

- Interview the patient to determine understanding of discharge instructions provided. If applicable to the instructions given to the patient being observed, the patient should understand:

- The purpose for taking any new medication;

- How to take the medication, including dose and frequency;

- The medication regimen, including continuation or discontinuation of medications taken prior to hospital admission;

- Possible side effects of medication;

- Contraindications between prescribed medications and over-the-counter medications and herbal remedies;

- Changes in diet and dietary restrictions or supplements;

- Signs and symptoms of potential problems and whom to call with questions and concerns;

- Information regarding continued self-care (i.e., wound care, activity);

- Follow-up process with physician(s); and

- Arrangements made for home health needs (i.e., oxygen therapy, physical therapy).

- Explore the patient’s perception of the discharge instructions. Does the patient believe the necessary information was given?

Continuity of Care Record

Recognizing that patients remain the primary vehicle for transporting basic health information between providers, JCAHO is exploring strategies related to the Continuity of Care Record (CCR). This approach acknowledges that electronic health records are—at this time—a goal rather than the norm. Patients typically transport basic health information between providers in the context of completing a basic set of information on a registration form that is attached to a medical clipboard, prior to outpatient appointments and admissions.

An accurate minimum data set, containing such items as medication lists, allergies, conditions, and procedures, would provide substantial value to providers and patients. JCAHO already requires that an accurate medication list be updated at discharge and made available to the patient and the subsequent provider of care, but other key pieces of patient data, such as diagnosis and procedures, as well as the means required to make these data available to the patient or to the next caregiver, are not currently required.

JCAHO is now considering how hospitals and other healthcare organizations could provide or update a clinically relevant minimum data set of summarized health information, such as that contained in the CCR. The CCR is a standard specification being developed jointly by ASTM International, the Massachusetts Medical Society, the Healthcare Information Management Systems Society (HIMSS), the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American Academy of Pediatrics.

JCAHO envisions a minimum data set that includes an accurate list of demographics, medical insurance, medications, diagnosis, past procedures, allergies, and current healthcare providers. It also desires a data set that can be provided to the patient or the patient’s authorized representatives—both as paper and in a fully transportable and interoperable digital format—that could be presented to subsequent caregivers. This summary health record would permit care providers within or outside the organization to review the patient’s important clinical information at the point of care and near the time of clinical decision-making. Subsequent care providers would then be able to update the patient’s minimum data set as appropriate.

In addition to providing caregivers with the most essential and relevant information necessary to ensure safe, quality care, such an approach would minimize the effort necessary to keep such information current. Healthcare providers would have easy access to the most recent patient assessment and the recommendations of the caregiver who last treated the patient.

Patient Involvement

JCAHO has sought to help healthcare organizations in assisting patients with the discharge planning process through its Speak Up education program, which urges people to take an active role in their own healthcare. “Planning Your Recovery” provides tips to help people get more involved in their care and obtain the information they need for the best possible recovery. Patients who understand and follow directions about their follow-up care have a greater chance of getting better faster; they are also less likely to go back to the hospital.

Specifically, the JCAHO education campaign advises patients to:

1. Find out about their condition. This includes knowing how soon they should feel better, getting information about their ability to do everyday activities such as walking or preparing meals, knowing warning signs and symptoms to watch for, enlisting the help of a family member of friend in the discharge process from the hospital, and getting the phone number of a person to call at the hospital if a problem arises.

2. Find out about new medicines. It is important to request written directions about new medicines and ask any questions before leaving the hospital. Other issues that JCAHO advises patients to consider include finding out whether other medicines, vitamins, and herbs could interfere with the new drugs and knowing whether there are any specific foods or drinks to avoid. Understanding the side effects of medications and any necessary restrictions on daily activities because of the potential for dizziness or sleepiness is also crucial.

3. Find out about follow-up care. This includes asking for written directions about cleaning and bandaging wounds, using special equipment, or doing any required exercises; finding out about follow-up visits to the hospital and making transportation arrangements for those visits; reviewing insurance to find out whether the cost of medicines and equipment needed for recovery will be covered; and determining whether home care services or a nursing home or assisted living center will be necessary for follow-up care.

JCAHO is joined in encouraging people to play an active role in planning their recovery by the National Alliance for Caregiving and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Care Planner. Practitioners who want to share this advice with their patients or wish to direct their patients to the information can go to JCAHO’s Web site, www.jointcommission.org, to download a free Speak Up brochure.

Conclusion

Ideally, discharge planning should be a smooth process facilitated by a personal health record that is controlled by the patient and that provides ready access to all of the patient’s health data that have been compiled from all the patient’s healthcare providers. Such a record would be accessible anywhere and at any time, over a lifetime. This concept remains in its infancy, however. Until such time as communication with patients and among providers is more transparent and less prone to error, The Joint Commission will continue to seek methods to better address this important aspect of providing safe, effective care. TH

Dr. Jacott, special advisor for professional relations at JCAHO, is the organization’s liaison to SHM. He also reaches out to state and specialty physician societies, hospital medical staffs, and other professional organizations.

The transition from hospital to home or to another care site is a high-risk period for the patient for a number of reasons, as we have discussed in The Hospitalist this year. Ineffective communication with the patient and between healthcare practitioners at discharge is common. In addition, primary care providers increasingly delegate inpatient care to hospitalists. This delegation of care can lead to gaps in knowledge that present risks to patient safety.

Further, information transfer among healthcare practitioners—whether they be primary care providers or hospitalists—and their patients is often compromised by record inaccuracies, omissions, illegibility, information never delivered, and delays in generation or transmission.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has identified recall error, increased clinician workloads, interface failures between physicians and clerical staff, and inadequate training of physicians to respect the discharge process as the root causes of deficiencies in the current process of information transfer at discharge. While an interoperable health information technology infrastructure for the nation could effectively address many issues related to discharge planning, such a solution is certainly many years away.

New Approaches

Given the fact that a nationwide, interoperable health information technology infrastructure is not yet a reality, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) is exploring multiple approaches for improving communication with patients and among practitioners in the discharge planning process. This article details those strategies and is meant to stimulate discussion and elicit suggestions for future approaches.

If you have any suggestions for improving the discharge planning process, e-mail us at ldionne@wiley.com. We’ll publish the most effective and intriguing responses in a future issue of The Hospitalist.

Discharge Planning Standards

Patients may be discharged from the hospital entirely or transferred to another level of care, treatment, and services; they may be reassigned to different professionals or settings for continued services. JCAHO standards require that the hospital’s processes for transfer or discharge be based on the patient’s assessed needs. To facilitate discharge or transfer, the hospital should assess the patient’s needs, plan for discharge or transfer, facilitate the discharge or transfer process, and help to ensure that continuity of care, treatment, and services is maintained.

These standards (found in the Provision of Care (PC), Ethics, Rights and Responsibilities (RI), and Management of Information (IM) chapters of the hospital accreditation manual) will be updated in July 2007. The changes include both new language and new requirements meant to improve communication with patients and among providers during the discharge planning process. Rather than a significant overhaul, these changes can be viewed as refinements to the existing standards that will help hospitals ensure that the intent of each standard is actually carried out to benefit patients. For example, an element of performance for standard PC.4.10 that addresses development of a plan of care now specifies that this process should be individualized to the patient’s needs. Another example is standard IM.6.20, for which an element of performance will require that the medical record contain medications dispensed or prescribed at discharge.

It is also important to note that JCAHO standards underscore the importance of the patient retaining information. Today, JCAHO requires—through its National Patient Safety Goals—that a list of current medications be provided to the patient at discharge. For patients who have been treated by a hospitalist, this requirement is especially important when they return to their primary care physicians for follow-up treatment.

Discharge Planning During the On-Site Survey

JCAHO began more closely examining discharge planning in 2005 by piloting a new process that surveyors used to evaluate standards compliance in 2006. The first option tested is a concurrent review in which surveyors observe the discharge instructions as they are being taught to the patient and then interview the patient about the content. The second option is a retrospective review and entails calling patients 24 to 48 hours after discharge to ascertain their understanding of the medication regimen and other instructions provided. Both options are used by JCAHO surveyors to understand how practitioners, nurses, and other caregivers carry out the hospital’s policies.

To help hospitalists understand how surveyors approach this process, the following summary provides information about the two review options.

Discharge Planning—Active Review

- Ask for a list of patients who will be discharged during the survey.

- Review the patient’s medical/clinical record for discharge orders.

- Request that the organization obtain patient permission to observe the discharge process.

- Observe the clinician providing discharge instructions. Components of the discharge instruction may include:

- Activity;

- Diet;

- Medications (post-discharge);

- Plans for physician follow-up;

- Wound care, if applicable;

- Signs and symptoms to be aware of (i.e., elevated temperature, medication side effects);

- The name and telephone number of a physician to call should a problem or question arise following discharge; and

- Patient repetition of information to confirm understanding.

- Review the written discharge instructions given to the patient. The discharge instructions are written in a language the patient can read and understand.

- Interview the patient to determine the patient’s level of understanding of discharge instructions. If applicable to the instructions given to the patient being observed, the patient should understand:

- The purpose for taking any new medication;

- How to take the medication, including dose and frequency;

- Possible side effects of medication;

- The medication regimen, including continuation or discontinuation of medications taken prior to hospital admission;

- Contraindications between prescribed medications and over-the-counter medications and herbal remedies;

- Changes in diet and dietary restric- tions or supplements;

- Signs and symptoms of potential problems and who to call with questions and concerns;

- Information regarding continued self-care (i.e., wound care, activity);

- Follow-up process with physician(s); and

- Arrangements made for home-health needs (i.e., oxygen therapy, physical therapy).

- Interview the nurse/clinician to ascertain the origination of discharge information (physician-nurse communication regarding discharge instruction).

Discharge Planning—Retrospective Review

- Ask for a list of patients discharged during the past 48 hours.

- Review the patient’s old medical record for discharge orders.

- Request that the organization stay with the surveyor as phone calls are made. The organization should first talk with the patient to explain the purpose of the call and obtain permission for a phone interview.

- Interview the patient to determine understanding of discharge instructions provided. If applicable to the instructions given to the patient being observed, the patient should understand:

- The purpose for taking any new medication;

- How to take the medication, including dose and frequency;

- The medication regimen, including continuation or discontinuation of medications taken prior to hospital admission;

- Possible side effects of medication;

- Contraindications between prescribed medications and over-the-counter medications and herbal remedies;

- Changes in diet and dietary restrictions or supplements;

- Signs and symptoms of potential problems and whom to call with questions and concerns;

- Information regarding continued self-care (i.e., wound care, activity);

- Follow-up process with physician(s); and

- Arrangements made for home health needs (i.e., oxygen therapy, physical therapy).

- Explore the patient’s perception of the discharge instructions. Does the patient believe the necessary information was given?

Continuity of Care Record

Recognizing that patients remain the primary vehicle for transporting basic health information between providers, JCAHO is exploring strategies related to the Continuity of Care Record (CCR). This approach acknowledges that electronic health records are—at this time—a goal rather than the norm. Patients typically transport basic health information between providers in the context of completing a basic set of information on a registration form that is attached to a medical clipboard, prior to outpatient appointments and admissions.

An accurate minimum data set, containing such items as medication lists, allergies, conditions, and procedures, would provide substantial value to providers and patients. JCAHO already requires that an accurate medication list be updated at discharge and made available to the patient and the subsequent provider of care, but other key pieces of patient data, such as diagnosis and procedures, as well as the means required to make these data available to the patient or to the next caregiver, are not currently required.

JCAHO is now considering how hospitals and other healthcare organizations could provide or update a clinically relevant minimum data set of summarized health information, such as that contained in the CCR. The CCR is a standard specification being developed jointly by ASTM International, the Massachusetts Medical Society, the Healthcare Information Management Systems Society (HIMSS), the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American Academy of Pediatrics.

JCAHO envisions a minimum data set that includes an accurate list of demographics, medical insurance, medications, diagnosis, past procedures, allergies, and current healthcare providers. It also desires a data set that can be provided to the patient or the patient’s authorized representatives—both as paper and in a fully transportable and interoperable digital format—that could be presented to subsequent caregivers. This summary health record would permit care providers within or outside the organization to review the patient’s important clinical information at the point of care and near the time of clinical decision-making. Subsequent care providers would then be able to update the patient’s minimum data set as appropriate.

In addition to providing caregivers with the most essential and relevant information necessary to ensure safe, quality care, such an approach would minimize the effort necessary to keep such information current. Healthcare providers would have easy access to the most recent patient assessment and the recommendations of the caregiver who last treated the patient.

Patient Involvement

JCAHO has sought to help healthcare organizations in assisting patients with the discharge planning process through its Speak Up education program, which urges people to take an active role in their own healthcare. “Planning Your Recovery” provides tips to help people get more involved in their care and obtain the information they need for the best possible recovery. Patients who understand and follow directions about their follow-up care have a greater chance of getting better faster; they are also less likely to go back to the hospital.

Specifically, the JCAHO education campaign advises patients to:

1. Find out about their condition. This includes knowing how soon they should feel better, getting information about their ability to do everyday activities such as walking or preparing meals, knowing warning signs and symptoms to watch for, enlisting the help of a family member of friend in the discharge process from the hospital, and getting the phone number of a person to call at the hospital if a problem arises.

2. Find out about new medicines. It is important to request written directions about new medicines and ask any questions before leaving the hospital. Other issues that JCAHO advises patients to consider include finding out whether other medicines, vitamins, and herbs could interfere with the new drugs and knowing whether there are any specific foods or drinks to avoid. Understanding the side effects of medications and any necessary restrictions on daily activities because of the potential for dizziness or sleepiness is also crucial.

3. Find out about follow-up care. This includes asking for written directions about cleaning and bandaging wounds, using special equipment, or doing any required exercises; finding out about follow-up visits to the hospital and making transportation arrangements for those visits; reviewing insurance to find out whether the cost of medicines and equipment needed for recovery will be covered; and determining whether home care services or a nursing home or assisted living center will be necessary for follow-up care.

JCAHO is joined in encouraging people to play an active role in planning their recovery by the National Alliance for Caregiving and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Care Planner. Practitioners who want to share this advice with their patients or wish to direct their patients to the information can go to JCAHO’s Web site, www.jointcommission.org, to download a free Speak Up brochure.

Conclusion

Ideally, discharge planning should be a smooth process facilitated by a personal health record that is controlled by the patient and that provides ready access to all of the patient’s health data that have been compiled from all the patient’s healthcare providers. Such a record would be accessible anywhere and at any time, over a lifetime. This concept remains in its infancy, however. Until such time as communication with patients and among providers is more transparent and less prone to error, The Joint Commission will continue to seek methods to better address this important aspect of providing safe, effective care. TH

Dr. Jacott, special advisor for professional relations at JCAHO, is the organization’s liaison to SHM. He also reaches out to state and specialty physician societies, hospital medical staffs, and other professional organizations.

The transition from hospital to home or to another care site is a high-risk period for the patient for a number of reasons, as we have discussed in The Hospitalist this year. Ineffective communication with the patient and between healthcare practitioners at discharge is common. In addition, primary care providers increasingly delegate inpatient care to hospitalists. This delegation of care can lead to gaps in knowledge that present risks to patient safety.

Further, information transfer among healthcare practitioners—whether they be primary care providers or hospitalists—and their patients is often compromised by record inaccuracies, omissions, illegibility, information never delivered, and delays in generation or transmission.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has identified recall error, increased clinician workloads, interface failures between physicians and clerical staff, and inadequate training of physicians to respect the discharge process as the root causes of deficiencies in the current process of information transfer at discharge. While an interoperable health information technology infrastructure for the nation could effectively address many issues related to discharge planning, such a solution is certainly many years away.

New Approaches

Given the fact that a nationwide, interoperable health information technology infrastructure is not yet a reality, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) is exploring multiple approaches for improving communication with patients and among practitioners in the discharge planning process. This article details those strategies and is meant to stimulate discussion and elicit suggestions for future approaches.

If you have any suggestions for improving the discharge planning process, e-mail us at ldionne@wiley.com. We’ll publish the most effective and intriguing responses in a future issue of The Hospitalist.

Discharge Planning Standards

Patients may be discharged from the hospital entirely or transferred to another level of care, treatment, and services; they may be reassigned to different professionals or settings for continued services. JCAHO standards require that the hospital’s processes for transfer or discharge be based on the patient’s assessed needs. To facilitate discharge or transfer, the hospital should assess the patient’s needs, plan for discharge or transfer, facilitate the discharge or transfer process, and help to ensure that continuity of care, treatment, and services is maintained.

These standards (found in the Provision of Care (PC), Ethics, Rights and Responsibilities (RI), and Management of Information (IM) chapters of the hospital accreditation manual) will be updated in July 2007. The changes include both new language and new requirements meant to improve communication with patients and among providers during the discharge planning process. Rather than a significant overhaul, these changes can be viewed as refinements to the existing standards that will help hospitals ensure that the intent of each standard is actually carried out to benefit patients. For example, an element of performance for standard PC.4.10 that addresses development of a plan of care now specifies that this process should be individualized to the patient’s needs. Another example is standard IM.6.20, for which an element of performance will require that the medical record contain medications dispensed or prescribed at discharge.

It is also important to note that JCAHO standards underscore the importance of the patient retaining information. Today, JCAHO requires—through its National Patient Safety Goals—that a list of current medications be provided to the patient at discharge. For patients who have been treated by a hospitalist, this requirement is especially important when they return to their primary care physicians for follow-up treatment.

Discharge Planning During the On-Site Survey

JCAHO began more closely examining discharge planning in 2005 by piloting a new process that surveyors used to evaluate standards compliance in 2006. The first option tested is a concurrent review in which surveyors observe the discharge instructions as they are being taught to the patient and then interview the patient about the content. The second option is a retrospective review and entails calling patients 24 to 48 hours after discharge to ascertain their understanding of the medication regimen and other instructions provided. Both options are used by JCAHO surveyors to understand how practitioners, nurses, and other caregivers carry out the hospital’s policies.

To help hospitalists understand how surveyors approach this process, the following summary provides information about the two review options.

Discharge Planning—Active Review

- Ask for a list of patients who will be discharged during the survey.

- Review the patient’s medical/clinical record for discharge orders.

- Request that the organization obtain patient permission to observe the discharge process.

- Observe the clinician providing discharge instructions. Components of the discharge instruction may include:

- Activity;

- Diet;

- Medications (post-discharge);

- Plans for physician follow-up;

- Wound care, if applicable;

- Signs and symptoms to be aware of (i.e., elevated temperature, medication side effects);

- The name and telephone number of a physician to call should a problem or question arise following discharge; and

- Patient repetition of information to confirm understanding.

- Review the written discharge instructions given to the patient. The discharge instructions are written in a language the patient can read and understand.

- Interview the patient to determine the patient’s level of understanding of discharge instructions. If applicable to the instructions given to the patient being observed, the patient should understand:

- The purpose for taking any new medication;

- How to take the medication, including dose and frequency;

- Possible side effects of medication;

- The medication regimen, including continuation or discontinuation of medications taken prior to hospital admission;

- Contraindications between prescribed medications and over-the-counter medications and herbal remedies;

- Changes in diet and dietary restric- tions or supplements;

- Signs and symptoms of potential problems and who to call with questions and concerns;

- Information regarding continued self-care (i.e., wound care, activity);

- Follow-up process with physician(s); and

- Arrangements made for home-health needs (i.e., oxygen therapy, physical therapy).

- Interview the nurse/clinician to ascertain the origination of discharge information (physician-nurse communication regarding discharge instruction).

Discharge Planning—Retrospective Review

- Ask for a list of patients discharged during the past 48 hours.

- Review the patient’s old medical record for discharge orders.

- Request that the organization stay with the surveyor as phone calls are made. The organization should first talk with the patient to explain the purpose of the call and obtain permission for a phone interview.

- Interview the patient to determine understanding of discharge instructions provided. If applicable to the instructions given to the patient being observed, the patient should understand:

- The purpose for taking any new medication;

- How to take the medication, including dose and frequency;

- The medication regimen, including continuation or discontinuation of medications taken prior to hospital admission;

- Possible side effects of medication;

- Contraindications between prescribed medications and over-the-counter medications and herbal remedies;

- Changes in diet and dietary restrictions or supplements;

- Signs and symptoms of potential problems and whom to call with questions and concerns;

- Information regarding continued self-care (i.e., wound care, activity);

- Follow-up process with physician(s); and

- Arrangements made for home health needs (i.e., oxygen therapy, physical therapy).

- Explore the patient’s perception of the discharge instructions. Does the patient believe the necessary information was given?

Continuity of Care Record

Recognizing that patients remain the primary vehicle for transporting basic health information between providers, JCAHO is exploring strategies related to the Continuity of Care Record (CCR). This approach acknowledges that electronic health records are—at this time—a goal rather than the norm. Patients typically transport basic health information between providers in the context of completing a basic set of information on a registration form that is attached to a medical clipboard, prior to outpatient appointments and admissions.

An accurate minimum data set, containing such items as medication lists, allergies, conditions, and procedures, would provide substantial value to providers and patients. JCAHO already requires that an accurate medication list be updated at discharge and made available to the patient and the subsequent provider of care, but other key pieces of patient data, such as diagnosis and procedures, as well as the means required to make these data available to the patient or to the next caregiver, are not currently required.

JCAHO is now considering how hospitals and other healthcare organizations could provide or update a clinically relevant minimum data set of summarized health information, such as that contained in the CCR. The CCR is a standard specification being developed jointly by ASTM International, the Massachusetts Medical Society, the Healthcare Information Management Systems Society (HIMSS), the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American Academy of Pediatrics.

JCAHO envisions a minimum data set that includes an accurate list of demographics, medical insurance, medications, diagnosis, past procedures, allergies, and current healthcare providers. It also desires a data set that can be provided to the patient or the patient’s authorized representatives—both as paper and in a fully transportable and interoperable digital format—that could be presented to subsequent caregivers. This summary health record would permit care providers within or outside the organization to review the patient’s important clinical information at the point of care and near the time of clinical decision-making. Subsequent care providers would then be able to update the patient’s minimum data set as appropriate.

In addition to providing caregivers with the most essential and relevant information necessary to ensure safe, quality care, such an approach would minimize the effort necessary to keep such information current. Healthcare providers would have easy access to the most recent patient assessment and the recommendations of the caregiver who last treated the patient.

Patient Involvement

JCAHO has sought to help healthcare organizations in assisting patients with the discharge planning process through its Speak Up education program, which urges people to take an active role in their own healthcare. “Planning Your Recovery” provides tips to help people get more involved in their care and obtain the information they need for the best possible recovery. Patients who understand and follow directions about their follow-up care have a greater chance of getting better faster; they are also less likely to go back to the hospital.

Specifically, the JCAHO education campaign advises patients to:

1. Find out about their condition. This includes knowing how soon they should feel better, getting information about their ability to do everyday activities such as walking or preparing meals, knowing warning signs and symptoms to watch for, enlisting the help of a family member of friend in the discharge process from the hospital, and getting the phone number of a person to call at the hospital if a problem arises.

2. Find out about new medicines. It is important to request written directions about new medicines and ask any questions before leaving the hospital. Other issues that JCAHO advises patients to consider include finding out whether other medicines, vitamins, and herbs could interfere with the new drugs and knowing whether there are any specific foods or drinks to avoid. Understanding the side effects of medications and any necessary restrictions on daily activities because of the potential for dizziness or sleepiness is also crucial.

3. Find out about follow-up care. This includes asking for written directions about cleaning and bandaging wounds, using special equipment, or doing any required exercises; finding out about follow-up visits to the hospital and making transportation arrangements for those visits; reviewing insurance to find out whether the cost of medicines and equipment needed for recovery will be covered; and determining whether home care services or a nursing home or assisted living center will be necessary for follow-up care.

JCAHO is joined in encouraging people to play an active role in planning their recovery by the National Alliance for Caregiving and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Care Planner. Practitioners who want to share this advice with their patients or wish to direct their patients to the information can go to JCAHO’s Web site, www.jointcommission.org, to download a free Speak Up brochure.

Conclusion

Ideally, discharge planning should be a smooth process facilitated by a personal health record that is controlled by the patient and that provides ready access to all of the patient’s health data that have been compiled from all the patient’s healthcare providers. Such a record would be accessible anywhere and at any time, over a lifetime. This concept remains in its infancy, however. Until such time as communication with patients and among providers is more transparent and less prone to error, The Joint Commission will continue to seek methods to better address this important aspect of providing safe, effective care. TH

Dr. Jacott, special advisor for professional relations at JCAHO, is the organization’s liaison to SHM. He also reaches out to state and specialty physician societies, hospital medical staffs, and other professional organizations.

No Shortcuts

Despite repeated warnings for more than 25 years by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) and other organizations, one of the major causes of medication errors is the ongoing use of potentially dangerous abbreviations and dose expressions. Root cause analyses information contained in the Joint Commission Sentinel Event Database shows that the underlying factors contributing to many of these medication errors are illegible or confusing handwriting by clinicians and the failure of healthcare providers to communicate clearly with one another.

Symbols and abbreviations are frequently used to save time and effort when writing prescriptions and documenting in patient charts; however, some symbols and abbreviations have the potential for misinterpretation or confusion. Examples of especially problematic abbreviations include “U” for “units” and “µg” for “micrograms.” When “U” is handwritten, it can often look like a zero. There are numerous case reports where the root cause of sentinel events related to insulin dosage has been the interpretation of a “U” as a zero. Using the abbreviation “µg” instead of “mcg” has also been the source of errors because when handwritten, the symbol “µ” can look like an “m.” The use of trailing zeros (e.g., 2.0 versus 2) or use of a leading decimal point without a leading zero (e.g. .2 instead of 0.2) are other dangerous order-writing practices. The decimal point is sometimes not seen when orders are handwritten using trailing zeros or no leading zeros. Misinterpretation of such orders could lead to a 10-fold dosing error.

A New Approach

As part of efforts to improve patient safety, the Joint Commission has long worked with hospitals to develop practical, cost-effective strategies that can be implemented at organizations regardless of unique characteristics, such as ownership, size, or location. One such Joint Commission initiative is a National Patient Safety Goal to improve communication. This goal and one of its requirements specifically addresses the role that abbreviations, acronyms, symbols, and dose designations play in medication errors.

The Joint Commission began establishing National Patient Safety Goals in 2002 as a means to target critical areas where patient safety can be improved through specific action in healthcare organizations. The resulting National Patient Safety Goals are designed to give focus to evidence-based or expert consensus-based, well-defined, practical, and cost-effective actions that have potential for significant improvement in the safety of individuals receiving care. New Goals are recommended annually by the Sentinel Event Advisory Group, a Joint Commission-appointed, multidisciplinary group of patient safety experts.

JCAHO Expectations

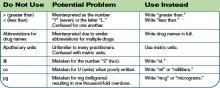

In order to comply with the National Patient Safety Goal related to abbreviations, an organization must conduct a thorough review of its approved abbreviation list and develop a list of unacceptable abbreviations and symbols with the involvement of physicians. In addition, organizations must do the following to meet this goal:

- The list of prohibited abbreviations, acronyms, symbols, and dose designations must be implemented for all handwritten, patient-specific communications, not just medication orders;

- These requirements apply to printed or electronic communications;

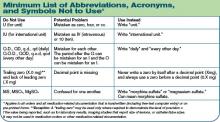

- This goal requires organizations to achieve 100% compliance with a reasonably comprehensive list of prohibited dangerous abbreviations, acronyms, symbols, and dose designations. This list need not be as extensive as some published lists, but must, at a minimum, include a set of Joint Commission-specified dangerous abbreviations, acro-nyms, symbols, and dose designations (see “Minimum List of Abbreviations, Acronyms, and Symbols Not to Use,” top right) and

- An abbreviation on the “do not use” list should not be used in any of its forms—uppercase or lowercase, with or without periods.

In addition to this minimum list, each organization should consider which abbreviations, acronyms, symbols, and dose designations it commonly uses; examine the risks associated with usage; and develop strategies to reduce usage. Hospitals also may wish to look to expert resources such as the Institute of Safe Medication Practices (ISMP)—available at www.ismp.org/Tools/abbreviationslist.pdf—and the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP)—available at www.nccmerp.org/dangerousAbbrev.html—to develop a list of prohibited abbreviations. Finally, organizations may wish to consider the Joint Commission list (see table below) of abbreviations, symbols, and acronyms for future possible inclusion in the official “do not use” list.

Risk Reduction Strategies

To comply with this National Patient Safety Goal Requirement, hospitals may wish to consider implementing the following risk reduction strategies:

- Examine medication error data in the organization. By identifying and selecting an organization-specific set of prohibited abbreviations, it will be much easier to gain support to eliminate certain abbreviations that have been found to be problematic at that organization.

- Provide simplified alternative abbreviations. For example, some staff members may resist writing out “international units” in place of “IU.” A simpler alternative such as “Intl Units” may be a solution.

- Make the list visible. Print the list on brightly colored paper or stickers and place it in patient charts.

- Provide staff with pocket-sized cards with the “do not use” list.

- Print the list in the margin or bottom of the physician order sheets and/or progress notes.

- Attach laminated copies of the list to the back of the physician order divider in the patient chart.

- Send monthly reminders to staff.

- Delete prohibited abbreviations from preprinted order sheets and other forms.

- Work with software vendors to ensure changes are made to be consistent with the list.

- Take a digital picture or scan the document containing the prohibited abbreviation and send it via e-mail directly to the offending prescriber to call attention to the issue.

- Direct the pharmacy not to accept any of the prohibited abbreviations. Orders with dangerous abbreviations or illegible handwriting must be corrected before being dispensed.

- Conduct a mock survey to test staff knowledge.

- At every staff meeting give patient safety updates, including information about the prohibited abbreviations.

- Ask all staff to sign a statement that he or she has received the list and agrees not to use the abbreviations.

- Promote a “do-not-use abbreviation of the month” policy.

- Develop and implement a policy to ensure that staff refer to the list and take steps to ensure compliance. Consider including a policy that states if an unacceptable abbreviation is used, the prescriber verifies the prescription order before it is filled.

- Monitor staff compliance with the list and offer additional education and training, as appropriate.

Conclusion

During the past decade, healthcare providers have been searching for more effective ways to reduce the risk of systems breakdowns that result in serious harm to patients. The Joint Commission is committed to working with organizations through the accreditation process on ways to anticipate and prevent errors. National Patient Safety Goals, such as the one associated with prohibited abbreviations, are one such method to promote specific improvements in patient safety. By using the principals of sound system design, organizations and providers further strengthen foundations that support safe, high-quality care. TH

Dr. Jacott is special advisor for professional relations for the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations.

Despite repeated warnings for more than 25 years by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) and other organizations, one of the major causes of medication errors is the ongoing use of potentially dangerous abbreviations and dose expressions. Root cause analyses information contained in the Joint Commission Sentinel Event Database shows that the underlying factors contributing to many of these medication errors are illegible or confusing handwriting by clinicians and the failure of healthcare providers to communicate clearly with one another.

Symbols and abbreviations are frequently used to save time and effort when writing prescriptions and documenting in patient charts; however, some symbols and abbreviations have the potential for misinterpretation or confusion. Examples of especially problematic abbreviations include “U” for “units” and “µg” for “micrograms.” When “U” is handwritten, it can often look like a zero. There are numerous case reports where the root cause of sentinel events related to insulin dosage has been the interpretation of a “U” as a zero. Using the abbreviation “µg” instead of “mcg” has also been the source of errors because when handwritten, the symbol “µ” can look like an “m.” The use of trailing zeros (e.g., 2.0 versus 2) or use of a leading decimal point without a leading zero (e.g. .2 instead of 0.2) are other dangerous order-writing practices. The decimal point is sometimes not seen when orders are handwritten using trailing zeros or no leading zeros. Misinterpretation of such orders could lead to a 10-fold dosing error.

A New Approach

As part of efforts to improve patient safety, the Joint Commission has long worked with hospitals to develop practical, cost-effective strategies that can be implemented at organizations regardless of unique characteristics, such as ownership, size, or location. One such Joint Commission initiative is a National Patient Safety Goal to improve communication. This goal and one of its requirements specifically addresses the role that abbreviations, acronyms, symbols, and dose designations play in medication errors.

The Joint Commission began establishing National Patient Safety Goals in 2002 as a means to target critical areas where patient safety can be improved through specific action in healthcare organizations. The resulting National Patient Safety Goals are designed to give focus to evidence-based or expert consensus-based, well-defined, practical, and cost-effective actions that have potential for significant improvement in the safety of individuals receiving care. New Goals are recommended annually by the Sentinel Event Advisory Group, a Joint Commission-appointed, multidisciplinary group of patient safety experts.

JCAHO Expectations

In order to comply with the National Patient Safety Goal related to abbreviations, an organization must conduct a thorough review of its approved abbreviation list and develop a list of unacceptable abbreviations and symbols with the involvement of physicians. In addition, organizations must do the following to meet this goal:

- The list of prohibited abbreviations, acronyms, symbols, and dose designations must be implemented for all handwritten, patient-specific communications, not just medication orders;

- These requirements apply to printed or electronic communications;

- This goal requires organizations to achieve 100% compliance with a reasonably comprehensive list of prohibited dangerous abbreviations, acronyms, symbols, and dose designations. This list need not be as extensive as some published lists, but must, at a minimum, include a set of Joint Commission-specified dangerous abbreviations, acro-nyms, symbols, and dose designations (see “Minimum List of Abbreviations, Acronyms, and Symbols Not to Use,” top right) and

- An abbreviation on the “do not use” list should not be used in any of its forms—uppercase or lowercase, with or without periods.

In addition to this minimum list, each organization should consider which abbreviations, acronyms, symbols, and dose designations it commonly uses; examine the risks associated with usage; and develop strategies to reduce usage. Hospitals also may wish to look to expert resources such as the Institute of Safe Medication Practices (ISMP)—available at www.ismp.org/Tools/abbreviationslist.pdf—and the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP)—available at www.nccmerp.org/dangerousAbbrev.html—to develop a list of prohibited abbreviations. Finally, organizations may wish to consider the Joint Commission list (see table below) of abbreviations, symbols, and acronyms for future possible inclusion in the official “do not use” list.

Risk Reduction Strategies

To comply with this National Patient Safety Goal Requirement, hospitals may wish to consider implementing the following risk reduction strategies:

- Examine medication error data in the organization. By identifying and selecting an organization-specific set of prohibited abbreviations, it will be much easier to gain support to eliminate certain abbreviations that have been found to be problematic at that organization.

- Provide simplified alternative abbreviations. For example, some staff members may resist writing out “international units” in place of “IU.” A simpler alternative such as “Intl Units” may be a solution.

- Make the list visible. Print the list on brightly colored paper or stickers and place it in patient charts.

- Provide staff with pocket-sized cards with the “do not use” list.

- Print the list in the margin or bottom of the physician order sheets and/or progress notes.

- Attach laminated copies of the list to the back of the physician order divider in the patient chart.

- Send monthly reminders to staff.

- Delete prohibited abbreviations from preprinted order sheets and other forms.

- Work with software vendors to ensure changes are made to be consistent with the list.

- Take a digital picture or scan the document containing the prohibited abbreviation and send it via e-mail directly to the offending prescriber to call attention to the issue.

- Direct the pharmacy not to accept any of the prohibited abbreviations. Orders with dangerous abbreviations or illegible handwriting must be corrected before being dispensed.

- Conduct a mock survey to test staff knowledge.

- At every staff meeting give patient safety updates, including information about the prohibited abbreviations.

- Ask all staff to sign a statement that he or she has received the list and agrees not to use the abbreviations.

- Promote a “do-not-use abbreviation of the month” policy.

- Develop and implement a policy to ensure that staff refer to the list and take steps to ensure compliance. Consider including a policy that states if an unacceptable abbreviation is used, the prescriber verifies the prescription order before it is filled.

- Monitor staff compliance with the list and offer additional education and training, as appropriate.

Conclusion

During the past decade, healthcare providers have been searching for more effective ways to reduce the risk of systems breakdowns that result in serious harm to patients. The Joint Commission is committed to working with organizations through the accreditation process on ways to anticipate and prevent errors. National Patient Safety Goals, such as the one associated with prohibited abbreviations, are one such method to promote specific improvements in patient safety. By using the principals of sound system design, organizations and providers further strengthen foundations that support safe, high-quality care. TH

Dr. Jacott is special advisor for professional relations for the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations.

Despite repeated warnings for more than 25 years by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) and other organizations, one of the major causes of medication errors is the ongoing use of potentially dangerous abbreviations and dose expressions. Root cause analyses information contained in the Joint Commission Sentinel Event Database shows that the underlying factors contributing to many of these medication errors are illegible or confusing handwriting by clinicians and the failure of healthcare providers to communicate clearly with one another.

Symbols and abbreviations are frequently used to save time and effort when writing prescriptions and documenting in patient charts; however, some symbols and abbreviations have the potential for misinterpretation or confusion. Examples of especially problematic abbreviations include “U” for “units” and “µg” for “micrograms.” When “U” is handwritten, it can often look like a zero. There are numerous case reports where the root cause of sentinel events related to insulin dosage has been the interpretation of a “U” as a zero. Using the abbreviation “µg” instead of “mcg” has also been the source of errors because when handwritten, the symbol “µ” can look like an “m.” The use of trailing zeros (e.g., 2.0 versus 2) or use of a leading decimal point without a leading zero (e.g. .2 instead of 0.2) are other dangerous order-writing practices. The decimal point is sometimes not seen when orders are handwritten using trailing zeros or no leading zeros. Misinterpretation of such orders could lead to a 10-fold dosing error.

A New Approach

As part of efforts to improve patient safety, the Joint Commission has long worked with hospitals to develop practical, cost-effective strategies that can be implemented at organizations regardless of unique characteristics, such as ownership, size, or location. One such Joint Commission initiative is a National Patient Safety Goal to improve communication. This goal and one of its requirements specifically addresses the role that abbreviations, acronyms, symbols, and dose designations play in medication errors.

The Joint Commission began establishing National Patient Safety Goals in 2002 as a means to target critical areas where patient safety can be improved through specific action in healthcare organizations. The resulting National Patient Safety Goals are designed to give focus to evidence-based or expert consensus-based, well-defined, practical, and cost-effective actions that have potential for significant improvement in the safety of individuals receiving care. New Goals are recommended annually by the Sentinel Event Advisory Group, a Joint Commission-appointed, multidisciplinary group of patient safety experts.

JCAHO Expectations

In order to comply with the National Patient Safety Goal related to abbreviations, an organization must conduct a thorough review of its approved abbreviation list and develop a list of unacceptable abbreviations and symbols with the involvement of physicians. In addition, organizations must do the following to meet this goal:

- The list of prohibited abbreviations, acronyms, symbols, and dose designations must be implemented for all handwritten, patient-specific communications, not just medication orders;

- These requirements apply to printed or electronic communications;

- This goal requires organizations to achieve 100% compliance with a reasonably comprehensive list of prohibited dangerous abbreviations, acronyms, symbols, and dose designations. This list need not be as extensive as some published lists, but must, at a minimum, include a set of Joint Commission-specified dangerous abbreviations, acro-nyms, symbols, and dose designations (see “Minimum List of Abbreviations, Acronyms, and Symbols Not to Use,” top right) and

- An abbreviation on the “do not use” list should not be used in any of its forms—uppercase or lowercase, with or without periods.

In addition to this minimum list, each organization should consider which abbreviations, acronyms, symbols, and dose designations it commonly uses; examine the risks associated with usage; and develop strategies to reduce usage. Hospitals also may wish to look to expert resources such as the Institute of Safe Medication Practices (ISMP)—available at www.ismp.org/Tools/abbreviationslist.pdf—and the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP)—available at www.nccmerp.org/dangerousAbbrev.html—to develop a list of prohibited abbreviations. Finally, organizations may wish to consider the Joint Commission list (see table below) of abbreviations, symbols, and acronyms for future possible inclusion in the official “do not use” list.

Risk Reduction Strategies

To comply with this National Patient Safety Goal Requirement, hospitals may wish to consider implementing the following risk reduction strategies:

- Examine medication error data in the organization. By identifying and selecting an organization-specific set of prohibited abbreviations, it will be much easier to gain support to eliminate certain abbreviations that have been found to be problematic at that organization.

- Provide simplified alternative abbreviations. For example, some staff members may resist writing out “international units” in place of “IU.” A simpler alternative such as “Intl Units” may be a solution.

- Make the list visible. Print the list on brightly colored paper or stickers and place it in patient charts.

- Provide staff with pocket-sized cards with the “do not use” list.

- Print the list in the margin or bottom of the physician order sheets and/or progress notes.

- Attach laminated copies of the list to the back of the physician order divider in the patient chart.

- Send monthly reminders to staff.

- Delete prohibited abbreviations from preprinted order sheets and other forms.

- Work with software vendors to ensure changes are made to be consistent with the list.

- Take a digital picture or scan the document containing the prohibited abbreviation and send it via e-mail directly to the offending prescriber to call attention to the issue.

- Direct the pharmacy not to accept any of the prohibited abbreviations. Orders with dangerous abbreviations or illegible handwriting must be corrected before being dispensed.

- Conduct a mock survey to test staff knowledge.

- At every staff meeting give patient safety updates, including information about the prohibited abbreviations.

- Ask all staff to sign a statement that he or she has received the list and agrees not to use the abbreviations.

- Promote a “do-not-use abbreviation of the month” policy.

- Develop and implement a policy to ensure that staff refer to the list and take steps to ensure compliance. Consider including a policy that states if an unacceptable abbreviation is used, the prescriber verifies the prescription order before it is filled.

- Monitor staff compliance with the list and offer additional education and training, as appropriate.

Conclusion

During the past decade, healthcare providers have been searching for more effective ways to reduce the risk of systems breakdowns that result in serious harm to patients. The Joint Commission is committed to working with organizations through the accreditation process on ways to anticipate and prevent errors. National Patient Safety Goals, such as the one associated with prohibited abbreviations, are one such method to promote specific improvements in patient safety. By using the principals of sound system design, organizations and providers further strengthen foundations that support safe, high-quality care. TH

Dr. Jacott is special advisor for professional relations for the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations.

A Trace of Improvement

The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) has dramatically redesigned and improved the value of its accreditation process. The new process includes revised standards, a periodic performance review (PPR), new survey techniques, and a revised decision process.

Known as Shared Visions-New Pathways and implemented in 2004, this transformation of the accreditation process has shifted the emphasis from survey preparation to continuous improvement of operational systems that contribute directly to the delivery of safe, high-quality care. The emphasis of the revised accreditation process is on how healthcare organizations normally provide care and use JCAHO standards as a framework to deliver safe care on a daily basis. There is a significant focus on clinical care.

This article explores the two major parts of this revised accreditation process: the patient tracer methodology that guides the on-site survey and the PPR, a self-assessment tool that results in corrective action plans. (These are particularly relevant for the hospitalist.)

Patient Tracer Methodology and the Hospitalist

The patient tracer methodology provides a framework for JCAHO surveyors to assess standards compliance and patient safety during on-site surveys. The process involves interviewing the caregivers to evaluate the quality and safety of the patient care process. By evaluating the actual delivery of care services, less time is devoted to examining written policies and procedures. Surveyors use 50%-60% of their time tracing the care of randomly selected patients to learn how staff from various disciplines work together and communicate across departments to provide safe, high-quality care.

One way surveyors look at how hospitals deliver safe, high-quality care is to interview hospitalists and other staff physicians. In the patient tracer methodology, the surveyor selects a patient and uses that patient’s care record as a roadmap to assess and evaluate the services that the healthcare organization provides. This type of interaction, coupled with an emphasis on continual compliance with standards such as infection control and medication management (which address issues crucial to good outcomes for patients), is exactly what physicians have told JCAHO they desire from the accreditation process.

The goal is not for the hospitalist to memorize JCAHO standards, but instead to be able to discuss patient care systems and processes. This is already an area with which hospitalists are familiar. Hospitalists are a vital part of the organizational structure and play a large role within the care systems. Hospitalists can help surveyors understand processes used within their healthcare organizations.

How Patient Tracers Work

Surveyors begin the patient tracer by starting where the patient is currently located. They then move to where the patient first entered the organization, and to any areas in the organization where the patient received care. Each tracer takes from one hour to three hours to complete. A three-day survey includes an average of 11 individual tracers.

For example, a surveyor might select a patient admitted to a hospital’s emergency department with cardiac disease. The patient went to cardiac cath, to the operating room for a CABG, and then to the intensive care unit. The patient had complications and ventilator-associated pneumonia. The surveyor would trace the patient’s path through the emergency department, cardiac cath area, operating room, post-anesthesia care unit, and intensive care unit.

The surveyor might focus on how each of these departments assessed the patient, obtained a medical history, developed the care plan, provided treatment, and addressed issues related to infection control. The surveyor also would return to the unit where the patient resides to discuss the findings as they explore the care processes. It may be that a new theme or area of focus—such as assessment and care/services—emerges from this tracer process. The surveyor would then explore this new area more thoroughly and ask other surveyors at the hospital to explore assessment and care/services in their tracers to determine if similar findings exist in other tracer patients.

Surveyors also may use the tracer methodology to examine how National Patient Safety Goals are addressed. On the surgical unit, a surveyor may observe a nurse giving medications ordered by the hospitalist. The surveyor would spend time talking with the nurse and hospitalist about the patient selected for the tracer, perhaps asking for the unique identifiers used for the patient. Other queries may include: What is the patient’s diagnosis? How is the hospitalist caring for this patient? What was the admission date? The surveyor would note whether any of the “do not use” abbreviations related to medications are used and talk with the hospitalist about this issue. How are healthcare-acquired infections addressed?

The patient tracer process takes surveyors across a wide variety of departments and involves practitioners and other caregivers in the accreditation process, asking them to describe how they carried out their work. Instead of asking the hospitalist about particular standards, surveyors explain the purpose of the tracer and engage in an educational as well as an evaluative process. This approach moves the on-site survey away from high-level conferences with administrators about policies and procedures to focused discussions with those actually delivering care. The idea is to create an atmosphere that allows for an open exchange of information and ideas between surveyors and the hospitalist and other staff.

These discussions with hospitalists, other staff, and patients—combined with review of clinical charts and the observations of surveyors—make for a dynamic survey process that provides a complete picture of an organization’s processes and services. In other words, the tracers allow surveyors to “see” care or services through the eyes of patients and staff and then analyze the systems for providing that care, treatment, or services.

As surveyors use the tracer methodology to determine standards of compliance as they relate to care delivered to individual patients, they also assess organizational systems by conducting patient-system tracers. The concept behind the patient-system tracers methodology, which focuses on high-risk processes across an organization, is to test the strength of the chain of operations and processes. By examining a set of components that work together toward a common goal, the surveyor can evaluate its level of efficiency and the ways in which an organization’s systems function. This approach addresses the interrelationships of the many elements that go into delivering safe, high-quality care and translates standards compliance issues into potential organization-wide vulnerabilities.

The system tracers provide a forum for discussion of important topics related to the safety and quality of care at the organization level. Surveyors use the system tracers to understand organization findings and to facilitate an exchange of educational information on key topics such as data use for infection control and medication management.

While some of the patient system tracer activities consist of formal interviews, an interactive session, which involves a surveyor and relevant staff members, is an important component of the process. Discussions in this interactive session with the hospitalist and other staff include:

- The flow of the processes, including identification and management of risk points, integration of key activities, and communication among staff/units involved in the process;

- Strengths in the processes and possible actions to be taken in areas needing improvement;

- Issues requiring further exploration in other survey activities; and

- A baseline assessment of standards compliance.

PPR and the Hospitalist

Beyond the onsite survey, JCAHO’s accreditation process is designed to help organizations maintain continuous compliance with the standards and use them as a daily management tool for improving patient care and safety. This represents a paradigm shift for the hospitalist, who may be more accustomed to organizations ramping up before an on-site survey. This frenzy of activity prior to an on-site survey did not meet the goals of JCAHO accreditation in that it drew physicians and staff away from providing care and managing performance improvement over time.

The PPR is a new form of evaluation conducted by the organization to assess its level of compliance with standards. This comprehensive, self-directed review provides the framework for continuous standards compliance and focuses on the critical systems and processes that affect patient care and safety. By conducting the PPR annually, organizations can self-evaluate their compliance with all Accreditation Participation Requirements, Standards and Evidence of Performance; develop plans of action to address any identified opportunities for improvement; and implement those plans to improve care.

JCAHO requires that physicians at accredited hospitals be involved in the self-assessment component of the PPR and in developing plans of action. Each hospital must make its own determinations about how involved hospitalists and other physicians are with the PPR. JCAHO recognizes that hospitalists have limited time for performance improvement activities, but believes that their participation is crucial because of their commitment to providing care that results in positive outcomes for patients and reduces risk.

Patient Tracer Methodology and PPR in 2006

As part of changes to the accreditation process, JCAHO will shift from scheduled to unannounced on-site surveys. The transition to unannounced surveys began this year:

- To enhance the credibility of the accreditation process by ensuring that surveyors observe organization performance under normal circumstances;

- To help healthcare organizations focus on providing safe, high quality care at all times, and not just when preparing for survey;

- To reduce the unnecessary costs that healthcare organizations incur to prepare for survey; and

- To address public concerns that JCAHO receive an accurate reflection of the quality and safety of care.

The new accreditation process supports this transition by considering the information generated by the PPR. Organizations will be able to update the PPR, available on each organization’s extranet site, annually to support continuous performance improvement efforts.

JCAHO conducted pilot testing of the unannounced survey process in volunteer organizations during 2004 and 2005, giving its staff insight into real-life issues and concerns at accreditation organizations. JCAHO also worked closely with its various advisory groups, accredited organizations and other stakeholder groups to gain their input and smooth the transition to unannounced surveys.

Conclusion

The participation of the hospitalist in the JCAHO accreditation process is dependent upon common interests in improving healthcare quality and safety. JCAHO accreditation can be used to help the hospitalist and healthcare organizations meet their goals and responsibilities to individual patients. Accreditation activities can help to focus physician involvement in patient safety and other important areas, thus bringing increased relevance to the accreditation process.

In conclusion, the importance of the hospitalist to the JCAHO accreditation process on a continuous basis, not just during the on-site survey, is crucial. TH

Dr. Jacott was appointed a special advisor for professional relations to the Joint Commission in January 2002. As special advisor for professional relations, Dr. Jacott serves as the Joint Commission’s liaison to SHM.