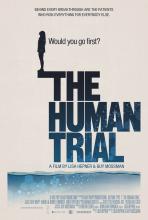

New data and a new documentary called “The Human Trial” together illuminate the hard work, sacrifice, and slow, iterative progress in the long search for a biological cure for type 1 diabetes.

Opening in select theaters on June 24, the film was written by Los Angeles filmmaker Lisa Hepner, who has type 1 diabetes, and codirected by Ms. Hepner and her husband Guy Mossman, who also filmed it. The couple co-own a film production company.

“The Human Trial” follows the personal journeys of two of the first participants in ViaCyte’s early phase 2 trial of stem cell–derived islet cell transplants, as well as those of the investigators and Ms. Hepner herself, who narrates and appears in the film, interweaving her own experience with type 1 diabetes while acting as a “bridge” between the trial’s participants and scientists. The film spans 7 years of the trial.

The timing of the film’s opening happens to follow presentations at two major medical meetings in early June of more recent islet cell transplantation data from ViaCyte and two other companies, Sernova and Vertex. Each is taking a different practical approach, with the most effective and safe technique yet to be determined.

But all are pursuing the same goal: A biological “cure” for type 1 diabetes with the aim of restoring fully functioning islet cells that can produce insulin and keep blood sugar levels in target range. Ultimately, the hope is to eliminate the need for both exogenous insulin and immunosuppression for all people with type 1 diabetes.

“Cell therapy is an attempt to drastically and substantially change the paradigm of how we actually treat type 1 diabetes,” Manasi S. Jaiman, MD, pediatric endocrinologist and chief medical officer at ViaCyte, said during a presentation at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Transplantation of cadaver-derived pancreatic islet cells to treat type 1 diabetes dates back more than 20 years to the landmark Edmonton Protocol, with many refinements since. About 1,500 recipients have received them, and roughly a quarter has maintained insulin independence after 10 years, Dr. Jaiman said.

More recently, islets derived from stem cells – either embryonic or autologous – have been used to address the supply and quality problems that arise from cadaveric (dead) donors.

Still, though, the need for lifelong immune suppression means the only current recipients are people with type 1 diabetes for whom the risk of diabetes outweighs that of immune suppression, such as those with hypoglycemic unawareness or extreme glucose swings.

Many research efforts are underway to counter the need for immune suppression by a variety of techniques including cell encapsulation or gene modification.

While the data thus far are encouraging, most of the reports align with what Ms. Hepner says in the film: “We all want stories with a beginning, middle, and end where all the loose pieces fit together. But clinical research is messy and hard. It doesn’t fit into a tidy headline, no matter how much you want it to.”