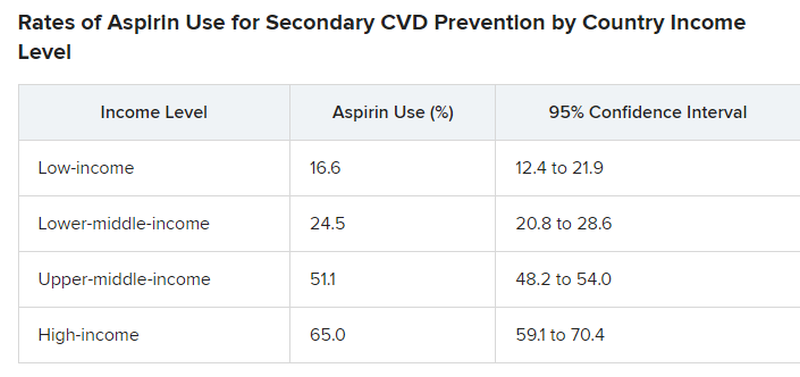

Nationally representative survey data from 51 countries showed that fewer than half of eligible people overall, including less than one-quarter in low-income and lower-middle–income countries, were taking aspirin for secondary CVD prevention.

“Our findings were not surprising but rather disappointing,” first author Sang Gune Yoo, MD, fellow in cardiovascular disease at Washington University in St Louis, said in an interview.

“We had hoped that the rates of aspirin use for secondary prevention would have increased after decades of effort to promote cardiovascular health worldwide,” Dr. Yoo said.

In high-income countries, such as the United States, rates of aspirin use for secondary CVD prevention were higher – at around 65% – but that’s also “really low and not particularly good or anything to be proud of,” Deepak Bhatt, MD, MPH, director of Mount Sinai Heart, New York, who wasn’t involved in the study, said in an interview.

The study was published online in JAMA. It provides the most extensive and up-to-date estimates of the worldwide use of aspirin for secondary prevention of CVD.

The researchers did a cross-sectional analysis using pooled, individual participant data from nationally representative health surveys conducted from 2013 to 2020 in 51 low-, middle-, and high-income countries.

The overall pooled sample included 124,505 nonpregnant adults (mean age, 52 years; 51% women). A total of 10,589 (8.1%) had a self-reported history of CVD and about 40% of these individuals were taking aspirin.

However, rates differed markedly by country, with use rates lowest in low-income and lower-middle–income countries and highest in upper-middle–income and high-income countries.

Primary vs. secondary prevention

The study did not explore the factors or reasons behind suboptimal aspirin use for secondary CVD prevention.

For example, it did not investigate whether data demonstrating that aspirin is not helpful in primary prevention is having a negative effect on use rates for secondary prevention. However, “rates of aspirin use for secondary prevention were low previously and remain suboptimal,” Dr. Yoo said.

Dr. Bhatt said that the “suboptimal” use of aspirin for secondary prevention is “a bit perplexing because this is a medicine that’s familiar, the data in secondary prevention are broadly known to physicians and it’s a cheap medicine so we can’t, in this case, blame high cost.”

Dr. Bhatt said it’s possible that coverage in the lay media of “negative” aspirin trials that may not distinguish between a primary and secondary prevention trial may contribute to confusion about aspirin. “In some cases, the doctor may think the patient is taking aspirin, but self discontinues it based on something they read or saw on the Internet.”

Dr. Yoo and colleagues said that, to meet the goal of reducing premature mortality from noncommunicable diseases, including CVD, “national health policies and health systems must develop, implement and evaluate strategies to promote evidence-based use of aspirin.”

“Strategies to boost appropriate aspirin use must be contextualized to the country and its health system,” Dr. Yoo added.

The study had no commercial funding. Dr. Yoo has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Bhatt disclosed receiving grants and/or personal fees from many companies, publications, and organizations.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.