“Critical Window” HT Timing Is Revealed

Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1353-1368.

After the initial 2002 publication of findings from the WHI trial of women with an intact uterus who were randomized to receive conjugated equine estrogens and medroxyprogesterone acetate or placebo, prominent news headlines claimed that HT causes myocardial infarction (MI) and breast cancer. As a result, millions of women worldwide stopped taking HT. A second impact of the report: Many clinicians became reluctant to prescribe HT.

Although it generated far less media attention, research published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in October 2013 details findings from a 13-year follow-up of WHI HT clinical trial participants and better informs clinicians and our patients about HT’s safety profile.

During the WHI intervention phase, absolute risks were modest

Although HT was associated with a multifaceted pattern of benefits and risks in both the estrogen-progestin therapy (EPT) and estrogen-only therapy (ET) arms of the WHI, absolute risks, as reflected in an increase or decrease in the number of cases per 10,000 women treated per year, were modest.

For example, the hazard ratio (HR) for coronary heart disease (CHD) during the intervention phase, during which participants were given HT or placebo (mean 5.2 years for EPT and 6.8 years for ET) was 1.18 in the EPT arm (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.95-1.45) and 0.94 in the ET arm (95% CI, 0.78-1.14). In both arms, women given HT had reduced risk for vasomotor symptoms, hip fractures, and diabetes, and increased risk for stroke, venous thromboembolism (VTE), and gallbladder disease, compared with women receiving placebo.

The results for breast cancer differed markedly between arms. During the intervention period, an elevated risk was observed with EPT while a borderline reduced risk was observed with ET.

Among participants older than 65 at baseline, the risk for cognitive decline was increased in the EPT arm but not in the ET arm.

Post intervention, most risks and benefits attenuated

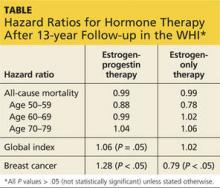

An elevation in the risk for breast cancer persisted in the EPT arm (cumulative HR over 13 years, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.11-1.48). In contrast, in the ET arm, a significantly reduced risk for breast cancer materialized (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.65-0.97) (see Table).

To put into perspective the elevated risk for breast cancer observed among women randomly allocated to EPT, the attributable risk is less than 1 additional case of breast cancer diagnosed per 1,000 EPT users annually. Another way to frame this elevated risk: An HR of 1.28 is slightly higher than the HR conferred by consuming one glass of wine daily and lower than the HR noted with two glasses daily.1

Overall, results tended to be more favorable for ET than for EPT. Neither type of HT affected overall mortality rates.

Age differences come to the fore

The WHI findings demonstrate a lower absolute risk for adverse events with HT in younger versus older participants. In addition, age and time since menopause appeared to affect many of the HRs observed in the trial. In the ET arm, more favorable results for all-cause mortality, MI, colorectal cancer, and the global index (CHD, invasive breast cancer, pulmonary embolism, colorectal cancer, and endometrial cancer) were observed in women ages 50 to 59 at baseline. In the EPT arm, the risk for MI was elevated only in women more than 10 years past the onset of menopause at baseline. Both HT regimens, however, were associated with increased risk for stroke, VTE, and gallbladder disease.

EPT increased the risk for breast cancer in all age-groups. However, the lower absolute risks for adverse events, and generally more favorable HRs for many outcomes, in younger women resulted in substantially lower rates of adverse events attributable to HT in the younger age-group, compared with older women.

As far as CHD is concerned, the impact of age (or time since menopause) on the vascular response to HT in women and in nonhuman models has generated support for a “critical window” or timing hypothesis, which postulates that estrogen reduces the development of early stages of atherosclerosis while causing plaque destabilization and other adverse effects when advanced atherosclerotic lesions are present. Recent studies from Scandinavia provide additional support for this hypothesis (see the sidebar).

REFERENCE

1. Chen WY, Rosner B, Hankinson SE, et al. Moderate alcohol consumption during adult life, drinking patterns, and breast cancer risk. JAMA. 2011;306(17):1884-190.

Continue for ACOG Guidance on menopausal symptoms >>