ORLANDO – A single injection of liraglutide can prevent ketogenesis in fasting patients with type 1 diabetes who were on basal insulin, findings from a small study have shown.

Husam Ghanim, Ph.D., research associate professor at the State University of New York at Buffalo, presented the results in a late-breaking oral presentation session at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.

In a previous trial (Diabetes Care. 2016;39:1027-35) of patients with type 1 diabetes who took liraglutide, which does not have Food and Drug Administration approval for use in type 1 diabetes, for 12 weeks, investigators observed decreases in blood glucose levels compared with placebo and decreases in glucagon concentrations following a meal compared with before starting liraglutide. When patients already taking liraglutide and insulin were put on dapagliflozin for 12 weeks, glucagon levels rose more with dapagliflozin compared to placebo, and urinary acetoacetate and beta-hydroxybutyrate (adjusted to creatinine) rose over baseline levels.

Some researchers have hypothesized that liraglutide might stimulate residual beta cells (or beta cell stem cells) in patients with type 1 diabetes to produce insulin, thereby reducing the need for exogenous insulin. Promising data from animal studies suggesting that the drug stimulated residual beta cells were not duplicated in human studies. But some evidence shows it may reduce insulin doses anyway, even in cases of patients with no C-peptide, which means they are not producing any insulin on their own (Diabetes Care 2011. 34:1463-8).

In their study, Dr. Ghanim and his associates therefore wanted to test the effect on glucagon, free fatty acid, and ketone levels of acute administration of liraglutide to patients with type 1 diabetes in an insulinopenic condition. They randomly assigned patients with type 1 diabetes, aged 18-75 years, with undetectable C-peptide and hemoglobin A1c less than 8.5%, to receive an injection of 1.8 mg of liraglutide (n = 8) or placebo (n = 8) the morning after an overnight fast, which continued for the 5 hours of the study.

Patients had their basal insulin dose from the night before but no further insulin unless they were on an infusion pump, which they continued. Subjects were excluded if they were taking a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist or a sodium/glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, if they had renal impairment, had type 1 diabetes for less than 1 year, or had various other comorbidities.

The liraglutide group was slightly older than the placebo group (46 vs. 43 years), had a higher HbA1c (7.7% vs. 7.6%), and higher systolic but lower diastolic blood pressure (130/73 vs. 121/78 mm Hg). Body mass index was around 30 kg/m2 for both groups.

In the placebo group, there was no change in the blood glucose concentrations during the study period, whereas the liraglutide group showed a decrease from a baseline of 175 mg/dL to 135 mg/dL at 5 hours (P less than .05). Glucagon levels were maintained in the placebo group but showed significant suppression from 82 ng/L to 65 ng/L in the liraglutide arm (P less than .05).

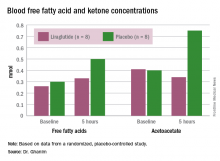

“Free fatty acid increased in both groups, but the increase in the placebo arm was significantly higher than that in the liraglutide group,” Dr. Ghanim said. Ketones increased in the placebo group but actually dropped in the liraglutide arm. Ghrelin levels rose by 20% in the placebo group and fell by 10% with liraglutide. Hormone-sensitive lipase decreased about 10% in both arms over the study period.

Dr. Ghanim proposed that since ghrelin is a mediator of lipolysis, possibly the suppression of ghrelin, as well as glucagon, by liraglutide “could contribute to the lower free fatty acid levels, which therefore leads to a lower ketogenic process and reduced ketone bodies.

“With the significant risk of DKA [diabetic ketoacidosis] in type 1 diabetics, especially when you have a drug like an SGLT2 inhibitor, which has been shown to be ketogenic, it is very important to know that liraglutide actually attenuates that response and reduces ketogenesis and therefore reduces the risk of DKA,” he said.

He suggested that these study results should lead to larger randomized trials of GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors, also not approved for use in type 1 diabetes, for use in this population because most of them are not presently well controlled and need additional agents.

Dr. John Miles, professor of both medicine and endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, Kansas, asked Dr. Ghanim why the study subjects did not vomit when receiving the dose of liraglutide. Dr. Ghanim responded that the subjects were not naive to it and had been on it previously.