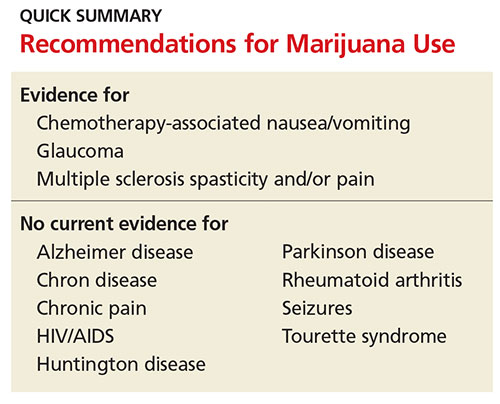

Marijuana has been used medicinally worldwide for thousands of years.1,2 In the early 1990s, the discovery of cannabinoid receptors in the central and peripheral nervous systems began to propagate interest in other potential therapeutic values of marijuana.3 Since then, marijuana has been used by patients experiencing chemotherapy-induced anorexia, nausea and vomiting, pain, and forms of spasticity. Use among patients with glaucoma and HIV/AIDS has also been widely reported.

In light of this—and of increasing efforts to legalize medical marijuana use across the United States—clinicians should be cognizant of the substance’s negative effects, as well as its potential health benefits. Marijuana has significant systemic effects and associated risks of which patients and health care providers should be aware. Questions remain regarding the safety, efficacy, and long-term impact of use. Use of marijuana for medical purposes requires a careful examination of the risks and benefits.

PHARMACOKINETICS

Marijuana contains approximately 60 cannabinoids, two of which have been specifically identified as primary components. The first, delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), is believed to be the most psychoactive.4,5 THC was identified in 1964 and is responsible for the well-documented symptoms of euphoria, appetite stimulation, impaired memory and cognition, and analgesia. The THC content in marijuana products varies widely and has increased over time, complicating research on the long-term effects of marijuana use.5,6

The second compound, cannabidiol (CBD), is a serotonin receptor agonist that lacks psychoactive effects. Potential benefits of CBD include antiemetic and anxiolytic properties, as well as anti-inflammatory effects. There is some evidence to suggest that CBD might also have antipsychotic properties.1,4

AVAILABLE FORMULATIONS

Two synthetic forms of THC have been approved by the FDA since 1985 for medicinal use: nabilone (categorized as a Schedule II drug) and dronabinol (Schedule III). Both are cannabinoid receptor agonists approved for treating chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. They are recommended for use after failure of standard therapies, such as 5-HT3 receptor antagonists, but overall interest has decreased since the advent of agents such as ondansetron.2,4

Nabiximols, an oral buccal spray, is a combination of THC and CBD. It was approved in Canada in 2005 for pain management in cancer patients and for multiple sclerosis–related pain and spasticity. It is not currently available in the US.2,4

Marijuana use is currently legal in 25 states and the District of Columbia.7,8 However, state laws regarding the criteria for medical use are vague and varied. For example, not all states require that clinicians review risks and benefits of marijuana use with patients. Even for those that do, the lack of clinical trials on the safety and efficacy of marijuana make it difficult for clinicians to properly educate themselves and their patients.9

LIMITATIONS OF RESEARCH

Why the lack of data? In 1937, a federal tax restricted marijuana prescription in the US, and in 1942, marijuana was removed from the US Pharmacopeia.2,4 The Controlled Substances Act in 1970 designated marijuana as a Schedule I drug, a categorization for drugs with high potential for abuse and no currently accepted medical use.9 Following this designation, research on marijuana was nearly halted in the US. Several medical organizations have subsequently called for reclassification to Schedule II in order to facilitate scientific research into marijuana’s medicinal benefits and risks.

Research is also limited due to the comorbid use of tobacco and other drugs in study subjects, the variation of cannabinoid levels among products, and differences in the route of administration—particularly smoking versus oral or buccal routes.5 Conducting marijuana research in a fashion similar to pharmaceuticals would not only serve the medical community but also the legislative faction.

Despite these obstacles, there is some available evidence on medical use of marijuana. A review of the associated risks and potential uses for the substance follows.