CE/CME

How to Increase HPV Vaccination Rates

Although accreditation for this CE/CME activity has expired, and the posttest is no longer available, you can still read the full article.

...

Janet Purath is an Associate Professor at Washington State University in Spokane, Washington. Theresa Coyner practices at Randall Dermatology, West Lafayette, Indiana.

The authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

Many of the 50 million persons affected by acne in the United States present to primary care. Acne severity guides treatment choices, which include topical antibiotics and retinoids, hormonal agents, and systemic antibiotics and retinoids. Formulating a treatment plan requires a thorough understanding of the dosing, mechanism of action, and potential adverse effects of available medications.

Acne vulgaris (acne) is a common skin condition that is frequently encountered in primary care. Acne affects up to 50 million people in the United States, and about 85% of teenagers experience it at some point.1 Costs for treatment exceed $3 billion per year.2 Although commonly considered a condition of adolescence and young adults (85% prevalence), acne may persist in both men and women well into their 30s and 40s (43% prevalence). In fact, 5% of women ages 40 and older may experience acne.3

Acne is associated with considerable, long-lasting psychological sequelae, even in those with mild conditions, as many affected patients experience self-esteem issues and may avoid social interactions.4 Recognition of patients’ concerns about acne will help to promote a trusting patient-provider relationship. This article describes the pathophysiology and classifications of acne and reviews therapeutic options, enabling the practitioner to initiate treatment.

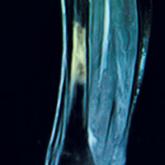

Acne lesions may occur on the face, neck, trunk, and extremities. The severity of acne is assessed based on lesion type, number, and size, and this grading is used to inform decisions about treatment options. Mild acne is characterized by plugging of the sebaceous gland (comedones), with small numbers of inflammatory papules and pustules. Moderate acne involves a larger number of inflammatory papules/pustules as well as the presence of small cystic nodules. Severe acne is marked by the presence of large numbers of noninflammatory and inflammatory lesions and cystic nodules or widespread involvement of these lesions.5 Examples of mild, moderate, and severe acne are shown in Figure 1. Assessment should include questions about the patient’s experiences with prior therapies.

The pathogenesis of acne is a complex process involving multiple factors (see Figure 2). Knowledge about acne pathogenesis continues to evolve, but the current view is that a combination of simultaneous noninflammatory and inflammatory events involving pilosebaceous units (which consist of sebaceous glands and hair follicles) contribute to its development.6 Activation of the sebaceous glands is influenced by androgens, which increase sebum production and shedding of the keratinocytes lining the gland. Plugging of the pilosebaceous canal ensues, leading to the development of a microcomedone. Increased proliferation of Propionibacterium acnes occurs within the obstructed gland. The inflammatory response to this process includes a cascade of numerous cytokines, most notably toll-like receptor 2 (TLR-2).7 The plug at the opening of the sebaceous gland creates either an open comedone (blackhead) or a closed comedone (whitehead). Eventually, the follicular wall ruptures, leading to the formation of erythematous papules and pustules on the skin surface or deep-seated cystic structures under the skin surface. Current pharmacologic agents target one or more of these identified factors underlying acne pathogenesis.

Pharmacologic treatment options for acne include topical, systemic, and hormonal agents. Topical and systemic therapies reduce inflammation and follicular plugging. Topical treatments include antibiotics, anti-inflammatories, and retinoids. Oral treatments include antibiotics, hormones, and retinoids. The clinician must have a thorough understanding of the actions, potential adverse reactions, and drug interactions of each proposed therapy prior to formulating a treatment plan.

Topical retinoids are the most effective comedolytic agents available.1 Since comedones are thought to be the precursor of all other acne lesions, retinoids are appropriate for cases in which comedones are seen.1 Retinoids belong to a class of compounds structurally related to vitamin A. Topical retinoids act by promoting normal follicular keratinocyte desquamation, which prevents obstruction of the pilosebaceous canal and thereby inhibits the formation of microcomedones.8

They also exhibit anti-inflammatory action via inhibition of TLR-2.9 The comedolytic and anti-inflammatory actions of topical retinoids make them a mainstay of acne treatment, although some patients are unable to tolerate their adverse effects, which include erythema and dryness related to increases in transepidermal water loss. Application of noncomedogenic emollients can improve these common effects.10 The newer micronized and time-release retinoid formulations may have less potential for irritation.8 Vehicle formulation and concentration also play a role in skin irritation, with gels and liquids and formulations with higher concentrations of retinoids generally causing more drying than creams and lower potency formulations.8 Table 1 summarizes the mechanisms of action, available formulations, and potential adverse effects of the topical retinoids and other topical agents.1,6,9-16

It is important to note that retinoids can adversely affect the developing fetus when absorbed in large quantities. Notably, tazarotene is assigned to pregnancy category X because when it is used to treat psoriasis, one of its approved indications, large surface areas may be treated, increasing absorption. Absorption amounts are extremely low when tazarotene is used to treat acne. Nevertheless, verification of a negative pregnancy test is recommended prior to initiating tazarotene therapy. Effective birth control measures should be utilized throughout therapy. Even though other commonly used retinoids (tretinoin and adapalene) are assigned to pregnancy category C, all topical retinoids should be avoided during pregnancy.9

As noted, patient education is key for increasing patient adherence to therapy. Patients should be instructed to use a small (pea-sized) amount of medication for the entire face. Providers should also inform patients that transient erythema and dryness can be expected, and that application of a noncomedolytic moisturizer may reduce irritation. Tretinoin is best used at night,1 and it is useful to advise that erythema and irritation associated with retinoid use can be reduced by initially using the medication every other night to every third night, gradually building up to nightly use.1

Although accreditation for this CE/CME activity has expired, and the posttest is no longer available, you can still read the full article.

...

Although accreditation for this CE/CME activity has expired, and the posttest is no longer available, you can still read the full article.

...

Although accreditation for this CE/CME activity has expired, and the posttest is no longer available, you can still read the full article.

...