In addition, the acupuncturist providing treatment in a trial is typically unblinded. This is also true of trials measuring other physical modalities, but it contributes to the debate surrounding the magnitude of placebo response in acupuncture studies.

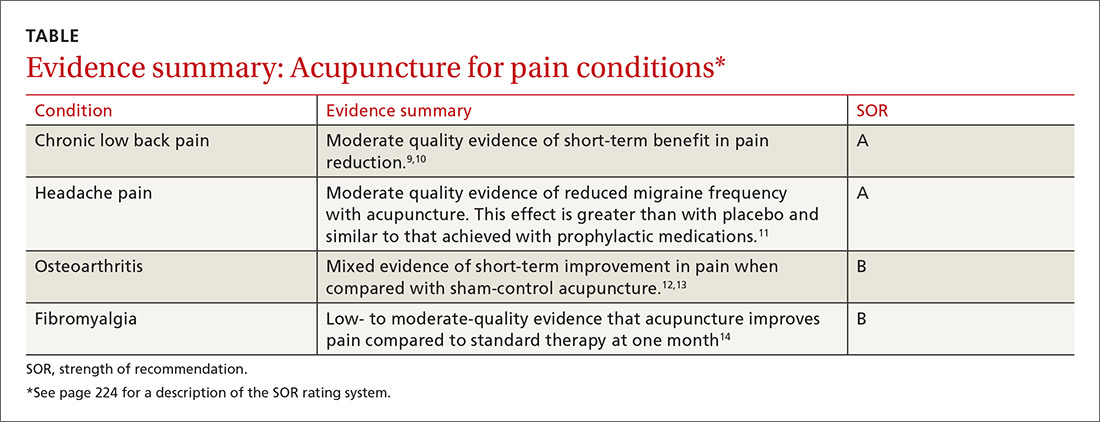

Finally, many randomized trials involving acupuncture have had low methodologic quality. Fortunately, there are now several high-quality systematic reviews that have attempted to filter out the lower-quality research and provide a better representation of the evidence (TABLE9-14). A discussion of them follows.

General chronic pain. A 2012 meta-analysis15 evaluated the effectiveness of acupuncture for the treatment of chronic pain with one of 4 etiologies: nonspecific back or neck pain, chronic headache, osteoarthritis, and shoulder pain. This analysis attempted to control for the high variability of study quality in the acupuncture literature by including only studies of high methodologic character. The final analysis included 29 randomized controlled trials (N=17,922). The authors concluded that acupuncture was superior to both no acupuncture and sham (placebo) acupuncture for all pain conditions in the study. The average effect size was 0.5 standard deviations on a 10-point scale. The authors considered this to be clinically relevant, although the magnitude of benefit was modest.15

Low back pain. A 2017 systematic review by Chou et al9 evaluated 32 trials (N=5931) reviewing acupuncture for the treatment of chronic low back pain. This review found acupuncture was associated with lower pain intensity and improved function in the short term when compared with no treatment. And while acupuncture was associated with lower pain intensity when compared with a sham control, there was no difference in function between the 2 groups. Of note, 3 of the included trials compared acupuncture to standard medications used in the treatment of low back pain and found acupuncture to be superior in terms of both pain reduction and improved function.9

The authors of a 2008 systematic review that evaluated 23 trials (N=6359)10 similarly concluded that there is moderate evidence for the use of acupuncture (compared to no treatment) for the treatment of nonspecific low back pain, but did not find evidence that acupuncture was superior to sham controls.10 The 2017 American College of Physicians clinical practice guidelines support the use of acupuncture for the treatment of chronic low back pain.16

In addition to helping with chronic low back pain, acupuncture is also showing promise as a treatment for acute spinal pain. A 2013 systematic review (11 trials, N=1139) showed that acupuncture may be more effective than nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in treating acute low back pain and may cause fewer adverse effects.17

Headache pain. Evidence favoring acupuncture in the management of headache has been fairly consistent over the past decade. An updated Cochrane review on the prevention of migraine headaches was published in 2016.11 Acupuncture was compared with no treatment in 4 trials (n=2199). The authors found moderate quality evidence that acupuncture reduces headache frequency (number needed to treat=4). Acupuncture achieved at least 50% headache reduction in 41% vs 17% in the groups that received no acupuncture. When compared with sham control groups (10 trials, n=1534), acupuncture demonstrated a small but statistically significant improvement in headache frequency. Three trials (n=744) compared acupuncture to medication prophylaxis for migraine headaches and found acupuncture had similar effectiveness with fewer adverse effects.11

Osteoarthritis (OA). Most studies have focused on OA of the knee, and, thus far, have generated conflicting results. A Cochrane review in 2010 included 4 trials (n=884) that had a wait list control and 9 trials (n=1835) that compared acupuncture to a sham control.12 When compared to a wait list control, acupuncture resulted in statistically significant and clinically relevant improvement in pain and function. However, when compared to sham treatment for OA, the review showed statistically significant improvement in pain and function for acupuncture that was unlikely to be clinically relevant.12

A more recent meta-analysis in 2016 evaluated 10 trials (N=2007) investigating acupuncture in the treatment of knee OA.13 The authors found acupuncture improved both pain and functional outcome measures when compared with either no treatment or a sham control.

Fibromyalgia. Systematic reviews in 2007 (5 trials, N=316)18 and 2010 (7 trials, N=385)19 showed that acupuncture did provide short-term pain relief in patients with fibromyalgia, but that the effect was not sustained at follow-up.These reviews were limited by a high risk of bias, which was noted in the studies. The authors of both reviews concluded that acupuncture could not be recommended for the treatment of fibromyalgia.

A more recent Cochrane review published in 2013 (9 trials, N=395) offered low- to moderate-level evidence of benefit for acupuncture compared with no treatment at one month follow-up.14 Of note, there was also evidence of benefit in improved sleep and global well-being, in addition to pain and stiffness measures in this review. The overall magnitude of benefit was small, but clinically significant. Acupuncture also has evidence of benefit in the treatment of conditions commonly seen in conjunction with fibromyalgia, including headaches and low back pain as described earlier.