On an autumn day, a 38-year-old woman with a history of asthma presented to the emergency department (ED) with the chief complaint of shortness of breath (SOB). The patient described her SOB as sudden in onset and not relieved by use of her albuterol inhaler; hence the ED visit.

She denied any chest pain, palpitations, dizziness, orthopnea, upper respiratory tract infection, cough, wheezing, fever or chills, headache, vision changes, body aches, sick contacts, or pets at home. She said she uses her albuterol inhaler as needed, and that she had used it that day for the first time in “a few months.” She denied any history of intubation or steroid use. Additionally, she had not been seen by a primary care provider in years.

The woman, a native of Ghana, had been living in the United States for many years. She denied any recent travel or exposure to toxic chemicals; any use of tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs; or any history of sexually transmitted disease.

The patient was afebrile (temperature, 98.6°F), with a respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min; blood pressure, 144/69 mm Hg; and ventricular rate, 125 beats/min. On physical examination, her extraocular movements were intact; pupils were equal, round, reactive to light and accommodation; and sclera were nonicteric. The patient’s head was normocephalic and atraumatic, and the neck was supple with normal range of motion and no jugular venous distension or lymphadenopathy. Her mucous membranes were moist with no pharyngeal erythema or exudates. Cardiovascular examination, including ECG, revealed tachycardia but no murmurs or gallops.

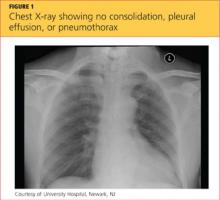

While being evaluated in the ED, the patient became tachypneic and began to experience respiratory distress. She was intubated for airway protection, at which time she developed pulseless electrical activity (PEA), with 30 beats/min. She responded to atropine and epinephrine injections. A repeat ECG showed sinus tachycardia and right atrial enlargement with right-axis deviation. Chest x-ray (see Figure 1) showed no consolidation, pleural effusion, or pneumothorax.

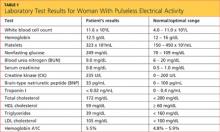

Results from the patient’s lab work are shown in the table, above. Negative results were reported for a urine pregnancy test.

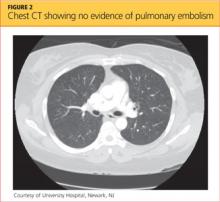

Since there was no clear etiology for the patient’s PEA, she underwent pan-culturing, with the following tests ordered: HIV antibody testing, immunovirology for influenza A and B viruses, and urine toxicology. Doppler ultrasound of the bilateral lower extremities was also ordered, in addition to chest CT and transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography (TTE and TEE, respectively). The patient was intubated and transferred to the medical ICU for further management.

The differential diagnosis included cardiac tamponade, acute MI, acute pulmonary embolus (PE), tension pneumothorax, hypovolemia, and asthma exacerbated by viral or bacterial infection.1,2 Although the case patient presented with PEA, she did not have the presenting signs of cardiac tamponade known as Beck’s triad: hypotension, jugular venous distension, and muffled heart sounds.3 TTE showed an ejection fraction of 65% and grade 2 diastolic dysfunction but no pericardial effusions (which accumulate rapidly in the patient with cardiac tamponade, resulting from fluid buildup in the pericardial layers),4 and TEE showed no atrial thrombi (which can masquerade as cardiac tamponade5). The patient had no signs of trauma and denied any history of malignancy (both potential causes of cardiac tamponade). Chest x-ray showed normal heart size and no pneumothorax, consolidations, or pleural effusions.4,6-8 Thus, the diagnosis of cardiac tamponade was ruled out.

Common presenting symptoms of acute MI include sudden-onset chest pain, SOB, palpitations, dizziness, nausea, and/or vomiting. Women may experience less dramatic symptoms—often little more than SOB and fatigue.9 According to a 2000 consensus document from a joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology committee10 in which MI was redefined, the diagnosis of MI relies on a rise in cardiac troponin levels, typical MI symptoms, and changes in ECG showing pathological Q waves or ST elevation or depression. The case patient’s troponin I level was less than 0.02 ng/mL, and ECG did not reveal Q waves or ST-T wave changes; additionally, since the patient had no chest pain, palpitations, diaphoresis, nausea, or vomiting, acute MI was ruled out.

Blood clots capable of blocking the pulmonary artery usually originate in the deep veins of the lower extremities.11 Three main factors, called Virchow’s triad, are known to contribute to these deep vein thromboses (DVTs): venous stasis, endothelial injury, and a hypercoagulability state.12,13 The patient had denied any trauma, recent travel, history of malignancy, or use of tobacco or oral contraceptives, and the result of her urine pregnancy test was negative. Even though the patient presented with tachypnea and acute SOB, with ECG showing right-axis deviation and tachycardia (common presenting signs and symptoms for PE), her chest CT showed no evidence of PE (see Figure 2); additionally, Doppler ultrasound of the bilateral lower extremities revealed no DVTs. Thus, PE was also excluded.