Additional Steps Before Initiating Treatment

After screening and diagnostic evaluation provide evidence that a patient is opioid dependent, you can take several steps to guide him or her to the appropriate treatment.

A thorough biopsychosocial assessment covering co-occurring psychiatric illnesses, pain, psychosocial stressors contributing to opioid use, and infectious disease screening is required to gain a clear picture of the patient's situation. In every case, acute emergencies such as suicidal ideation require immediate intervention, which may include hospitalization.19

Assess the patient's desire for help. After the initial assessment, it is often helpful to categorize the patient's "stage of change" (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, or maintenance)20 and to tailor your next step accordingly. A patient who denies that opioid use is a problem or who is clearly ambivalent about seeking treatment may require a conversation that uses principles of motivational interviewing—a collaborative approach that aims to evoke and strengthen personal motivation for change.21 Consider a question that encourages him or her to express reasons for change, such as: "How would you like your current situation to be different?" As almost everyone abusing opioids has thoughts about stopping, such a question may help the patient focus on specific changes.

CASE When you question Sam about his interest in oxycodone, he breaks down. He's been unable to find work or to lose the excess weight he gained during the many months he cared for his wife. He tells you that soon after his wife stopped taking the pain pills, he started taking them. At first, he took one occasionally. Then he started taking the opioids every day, and finally, whenever he awakened at night. Now, Sam says, he has no more pills, and he's nauseous, depressed, and unable to sleep—and looking to you for help.

Sam fits the criteria for opioid withdrawal as a result of physiological dependence; further questioning reveals that he also suffers from opioid dependence, and that he is receptive to treatment.

Recommending Treatment and Following Up

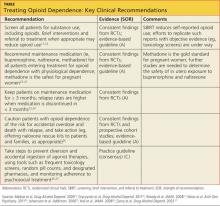

Several options are available for patients who, like Sam, have signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal as a result of physiological dependence. You can provide a referral to a clinician who specializes in addiction, recommend detoxification and/or treatment in an inpatient facility, or initiate pharmacologic treatment and provide a referral to a behavioral therapist. Whatever the initial approach, most patients will ultimately be treated as outpatients, with a combination of pharmacotherapy and behavioral therapy—often, with monitoring and oversight by a primary care provider. Which approach to pursue should be guided by evidence-based recommendations (see table17,22-27) and jointly decided by provider and patient.

Medication Plays a Key Role in Recovery

Recommend medication-assisted treatment, either with an agonist (buprenorphine or methadone) or an antagonist (naltrexone), for every patient with physiological opioid dependence. The goals of pharmacotherapy are to prevent or reduce withdrawal symptoms and craving, avoid relapse, and restore to a normal state any physiological functions (eg, sleep, bowel habits) that have been disrupted by opioid use.28 When continued for at least three months, medication has been shown to improve outcomes.23,24,29 In one recent study, 49% of opioid-dependent participants who were still taking buprenorphine-naloxone at 12 weeks had successful outcomes (minimal or no opioid use), compared with 7% of those undergoing a brief buprenorphine-naloxone taper.24

There are risks associated with medication-assisted therapy, however. Those of greatest concern are a potential increase in drug interactions, the risk of diversion (a concern with both buprenorphine and methadone), and the potential for accidental overdose.2,30

Buprenorphine, a partial m-opioid receptor agonist, is a Schedule III controlled substance and can be dispensed by a pharmacist, making inpatient opioid detoxification unnecessary for many opioid-dependent patients. Clinicians who wish to prescribe buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid dependence must complete an 8-hour course, offered by the American Medical Association and the APA, among other medical groups, and obtain a Drug Enforcement Administration (code "X") license.31

Buprenorphine has a high affinity for, and a slow dissociation from, m-opioid receptors, resulting in the displacement of other opioids from the m receptor and less severe withdrawal.32 As a partial agonist, buprenorphine attenuates opioid withdrawal symptoms with a ceiling, or near-maximal, effect at 16 mg, thereby lowering the risk for overdose.33 A sublingual formulation that combines buprenorphine with naloxone, an opioid antagonist that exerts its full effect when injected but is minimally absorbed sublingually, reduces the potential for abuse of buprenorphine without interfering with its effectiveness.34

Compared with methadone, buprenorphine is less likely to interact with antiretroviral medications or to cause QTc prolongation, erectile dysfunction, or cognitive or psychomotor impairment.31,35-37 Limitations include the ceiling effect, which can be a problem for cases in which more agonist is needed; cost (approximately $12/d); and the lack of approval by the FDA for use during pregnancy.