At some time or other, we’ve each been the clinician who suddenly became the patient; an entirely new level of confusion, frustration, and anxiety appears when the patient is your child. Hard enough to wear the two hats of clinician and patient—but trying to be a clinician and a parent at the same time is an entirely different matter.

During his pre-adolescent years, my son complained of stomachaches, nausea, and fatigue. Guzzling Gatorade seemed to help—he called it “magic juice.” His baseball teammates, understandably, started putting pressure on him to keep up. I wanted him to experience teamwork but decided that signing him up for another season would not be good for his self-esteem.

By the time he was 12, his symptoms had progressively worsened. Although he loved to swim, he would come out of the water shivering excessively, looking pale and mottled. He started to have trouble focusing on his schoolwork and said he often felt like collapsing in gym class. Sleepovers wiped him out for two or three days. Occasionally, he had bouts of restlessness after standing for long periods, followed by days of fatigue and stomachaches. He was always excessively thirsty. A glass or two of milk could calm him when he was restless or irritable or perk him up when he was fatigued.

At his annual physical, his weight was low, and his height had plateaued on the growth chart. It had actually been 18 months since his last physical, because of a change to new health insurance. In the days that followed, his symptoms became episodic and seemed to be aggravated by activity. Even a 15-minute walk required a break. Essentially, he was fine if he stayed at rest, but this was no way for a 12-year-old to live.

In pursuit of answers, I made an appointment for him with an endocrinologist and a urologist. Of course, my son looked fine once we got there—just like all the other times I’d whisked him to the doctor after a crippling episode. The test results were inconclusive.

After a number of calls to pick up my son at school, I made another appointment with the pediatrician. I explained again that his symptoms seemed to wax and wane under different conditions. The doctor considered severe constipation, but an abdominal x-ray was inconclusive.

The pediatrician then told my son that he must go to school unless he had a temperature of at least 100.4°F. It was heart wrenching to force him to go when he felt so miserable. “Mom, when I feel sick, my legs can barely carry me to class,” he said. “The doctor doesn’t understand.” He did not feel he was being taken seriously.

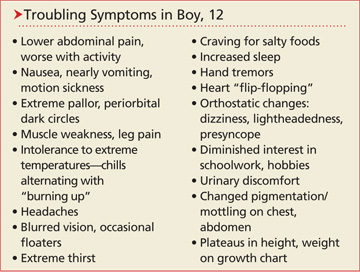

For a comprehensive evaluation, I scheduled time off from work and took him to a children’s hospital, with a list of his episodic symptoms (see box).

At the hospital, many tests were run, including blood work, MRI, an eye exam, and a resting ECG. I asked if my son could be put on a treadmill to “recreate” his symptoms, but my request went unheeded. He was discharged with a diagnosis of abdominal migraines.

During our visit to the gastroenterologist to schedule a colonoscopy and endoscopy, my son was not feeling well. After sitting up on the exam table, he turned sheet-white. The doctor referred us to a cardiologist.

I was convinced this would be another trudge to another appointment with more inconclusive results. The cardiology appointment included a tilt table test, ultrasound, and a stress test. The cardiologist’s conclusion: postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS). Finally, a proper diagnosis!

The cardiologist recommended increased salt and fluids to offset my son’s low fluid volume and the pooling of blood in his lower extremities. An abdominal binder was ordered, along with cardiac conditioning to build up his muscle tone—with a goal to keep the blood in his upper body and head.

My son had missed 30 days of school in eighth grade, and I had missed a lot of work. As we pursued further treatment, low-dose fluoxetine was suggested for secondary anxiety and its alpha-adrenergic effects on the vasculature. This was somewhat helpful, but my son was still intolerant of exercise and came home from school wiped out. Without his daily “dose” of Gatorade, he struggled to make it through the day. Standing at a lab station in class, he said, was intolerable.

I scheduled a consult at the Autonomic Disorders Clinic at the University of Toledo. There, my son finally felt validated, since he had many of the cardinal symptoms of POTS. Also, we were told that he is not the only teenager who refuses to wear an abdominal binder or support hose! He was started on fludrocortisone 0.1 mg every morning.