1.”I CAN’T SEE”

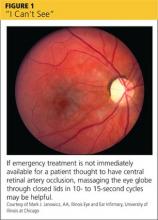

Patients may use words and phrases such as “cloudy vision,“ “a veil over my eyes,” or “fuzziness” to describe diminished vision. Some will report black areas within their visual field; others will have a loss of peripheral vision or total vision loss in one eye, or possibly even both. Some causes of vision problems, such as cataracts, are not emergencies. Causes of more severe (but painless) vision loss include central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO; see Figure 1) or vein occlusion (CRVO), giant cell arteritis (GCA), stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION), and nonorganic (functional) vision loss (see Table).1-11

When the cause is ischemic

Patients with CRAO experience acute loss of vision in one eye, usually occurring within seconds to minutes. Most patients with CRVO will have a similar presentation, depending on the presence or absence of ischemia and involvement of the macula. Those with branch retinal vein occlusion may have no vision loss at all.1-3

Risk factors for CRAO include cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, and other disorders associated with systemic inflammation. In patients older than 60, it is also important to consider GCA (to be discussed shortly) as a cause of CRAO.

In patients with CRAO, an eye exam will show profoundly decreased visual acuity, and the swinging light test (see “Use this mnemonic to ensure a comprehensive eye exam”) will reveal a relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD). Fundoscopy is diagnostic, revealing a pale retina due to decreased blood flow.4 Emergent referral to ophthalmology is indicated to establish a definitive diagnosis and initiate treatment based on the cause of the occlusion. If emergency care is not immediately available, massaging the eye globe through closed lids, then releasing, in 10- to 15-second cycles, may be helpful.5

Risk factors for CRVO include age older than 65 and a number of chronic conditions. One analysis attributed 48% of cases to hypertension, 20% to hyperlipidemia, and 5% to diabetes.3 Fundoscopy will reveal dilated veins, retinal hemorrhages, and cotton wool spots, which look like puffy white patches on the retina.6

As with CRAO, an urgent ophthalmology referral is critical to establish the diagnosis and develop a treatment plan. Outcomes are poor in patients with visual acuity of 20/200 or worse at the time of diagnosis.7,8

GCA. Patients with GCA may develop arteritic ischemic optic neuropathy, resulting in vision loss in one or both eyes. Risk factors for GCA include age (> 50), polymyalgia rheumatica, Caucasian race, and female sex. Systemic symptoms include fever, muscle aches, headache, jaw claudication, and scalp pain.6

The swinging light test will reveal an RAPD;1,2 fundoscopy findings typically include disk edema and disk hemorrhages, or a pale retina if GCA is associated with CRAO.6 Testing, including an erythrocyte sedimentation rate and a C-reactive protein, will provide supportive evidence, and biopsy of the temporal artery will confirm the diagnosis.4

Blindness from GCA is often profound. Bilateral disease is treated immediately with high-dose corticosteroids; when just one eye is affected, high-dose steroids should also be started right away to prevent vision loss in the other eye. Whenever GCA is suspected, initiate treatment and provide an urgent referral to an ophthalmologist for biopsy and further treatment.6

Strokes and TIAs that affect vision may be a result of ischemia of the visual cortex or the eye itself. Visual cortex ischemia will present as a homonymous visual field cut between the eyes; TIAs that affect only one eye (known as amaurosis fugax) are associated with ischemia to the optic nerve or retina.

Patients with amaurosis fugax will experience unilateral loss of vision that extends like a dark shade from the top or bottom periphery to the center of vision. When a TIA is the cause, vision will return to normal within minutes. The underlying pathology is usually carotid artery atherosclerosis. If left untreated, evidence suggests that 30% to 50% of patients will have a stroke within a month.9

Visual acuity may or may not be decreased, depending on whether the ischemia involves the macula. Symptoms suggestive of amaurosis fugax should prompt an urgent ophthalmology referral, while patients with persistent vision loss or visual field deficit require urgent referral to a stroke treatment center.9

NAION is also associated with acute monocular vision loss, particularly in older patients.10 Visual acuity will be markedly decreased, and fundoscopic exam will show a swollen and hemorrhagic optic disc. The vision loss can be profound and is usually permanent; neither medical nor surgical treatment has been shown to improve outcomes.10

When the cause is functional

Functional (nonorganic) visual disturbances should also be considered when sudden blindness is reported. Nonorganic vision loss has a number of causes, and patients present with a range of chief complaints, making diagnosis complex. Because some patients will have organic disease with a component of functional vision loss, it is best to refer individuals whom you suspect of having functional vision loss to an ophthalmologist for testing and a definitive diagnosis. Treatment includes psychological support and reassurance that vision will return.11

Continue for the second problem... "I'm seeing things"