It is often the case that children with disabilities do not report abuse because they are unable to recognize an act as abusive. Depending on the severity of a child’s disability and his or her ordinarily atypical presentation, the abuse may never be discovered.15

Poverty appears to be a contributing factor. Children from families of low socioeconomic status are at least three times as likely as other children to be abused and seven times as likely to experience neglect.14 It has been conjectured that these children are more likely to have contact with social workers, law enforcement officers, and representatives of other agencies with an increased awareness of the manifestations of child abuse. Abuse within affluent families may be underreported, as such families have the wherewithal to protect themselves from detection and prosecution.16

PRESENTATION

There is no “gold standard” for making a confirmed diagnosis of child abuse,17 and no “typical” presentation of an abused child (see case study). Dress that is inappropriate for the season and consistently poor hygiene are indicative of neglect. Symptoms of abuse may be overt or silent, and signs of physical abuse are often hidden beneath clothing. Children who are physically abused often explain their injuries by saying “I fell,” or may even respond to questioning by saying, “I don’t know.” The parent or caregiver may attribute bruises or even broken bones to falls or rough play with other children. Bruises, the most common visible form of child abuse,18 may suggest the nature of injury by their location, patterns, and various stages of healing.

Fractures are the second most common presenting symptom among children experiencing physical abuse.17 According to findings from a meta-analysis by Kemp et al,19 determining whether fractures have occurred accidentally depends on three factors:

Age. Among children younger than 1 year, 25% to 56% of fractures are attributable to intentional harm. In one landmark study, one fracture in nine was found to have resulted from abuse, among children younger than 18 months—compared with one in 205 among children ages 19 months to 5 years.19,20

Site. In cases not involving a motor vehicle accident or other traumatic event, it has been determined in ongoing systematic reviews by Welsh researchers that rib fractures have a 71% probability of being inflicted, followed by humeral fractures (about 50% probability), then by femoral fractures or skull fractures (about 33% probability).19,21

Fracture type. Fracture types suggestive of abuse differ by site. Among humeral fractures, for example, a midshaft fracture is more likely to have been inflicted, whereas a supracondylar fracture is more likely the result of accidental injury. Both parietal and linear skull fractures may occur accidentally or through physical abuse.19 Epiphyseal-metaphyseal fractures, vertebral compression fractures, and lateral clavicle fractures have been associated with child abuse.22,23 Multiple or bilateral fractures have an increased association with abuse.19,20,24

Injuries that are inconsistent with the given history should raise red flags, and they should be carefully investigated, with findings documented. Minor falls cause minor injuries, not potentially life-threatening ones.

As with fractures, burns may have specific features that help the clinician distinguish between accidental and intentional. Uniform depth, well-defined edges, and multiple lesions are more likely to indicate nonaccidental contact burns, particularly when found in “protected” sites (eg, perineal and gluteal areas).18 Accidental cigarette burns are usually ovoid or irregular in shape and superficial, while those intentionally inflicted are round, deep, and well-demarcated and are often grouped on the hands, feet, or face.18,25 Burns on the chest, upper limbs, and palms of the hands are likely to be accidental; the face, the backs of the hands, the lower stomach, back, buttocks, legs, and feet are often the target of intentional burns.18,26

HISTORY

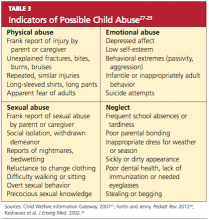

A key factor in suspected abuse is the child’s history. During history taking, clinicians should be alert to the evidence-based indicators of potential child abuse, as shown in Table 327-29. Not every child who exhibits these characteristics is an abused child, nor will every abused child exhibit any or all of these characteristics. Through artful, careful history taking and astute observation of the child, the clinician is usually able to distinguish between the heightened anxiety that may occur in any child during the history-taking process and the demeanor of a child who may have been coerced or threatened to maintain secrecy.

Engaging the child in a reassuring manner, the clinician can use a conversational style of questioning, such as, “Tell me how you got that bruise on your arm,” rather than a direct question: “Did [name] hit you on the arm with [his/her] fist?”