PUMP OPTIONS AND GLUCOSE MONITORING

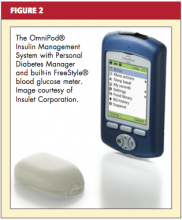

In addition to using wireless communication, current “disposable” (“patch”) pumps operate without the conventional infusion set and tubing. Some smart pumps are now equipped with a combination device: a diabetes-specific, PDA-like apparatus with an integrated glucose monitor that links to the pump through infrared technology (see Figure 2). Another pump has a “linked” glucose monitor (see Figure 3) that allows the user to test blood sugar, with the reading downloaded to the pump. The pump (or PDA) calculates the needed dose, based on programmed insulin-to-carbohydrate ratios and correction factors.22

A bolus calculator on the PDA helps the user calculate the bolus dose to be delivered to the pump without the user’s having to remove the pump to administer a dose. The pumper can discreetly administer insulin, even when the patient is eating out.

The one patch pump that is currently on the market requires the user to set the PDA to bolus, since the pod has no buttons with which to input instructions for a bolus. Use of the PDA or linked meter requires the pumper to use a particular brand of test strips. If insurance does not cover that brand, the patient can use another manufacturer’s monitor and enter blood sugar readings manually.

Potential Pump Problems

Patients who are considering any CSII pump must be willing to check blood glucose levels frequently. Malfunction of insulin pumps (including a blockage or pump failure) is associated with an increased risk for DKA,8 because the pump delivers only short-acting insulin. Without the presence of long-acting insulin as a backup, DKA can develop rapidly. All pumps have pressure-sensing alarms to detect blockages; in patients who receive small doses of insulin, however, it may take time for the alarm to be triggered. Thus, the importance of frequent blood glucose monitoring is evident. (Additionally, in case of pump failure, patients should know their basal rates and insulin-to-carbohydrate ratios or keep them written down.)

Pumpers are taught that if they experience two or more unexplained high glucose readings in a row to troubleshoot the infusion set for air bubbles or a clog. They should also take an injection of insulin to correct the high glucose and change the reservoir and infusion set.

Continuous Glucose Monitor

Some patients use continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) with a sensor that measures glucose levels in the interstitial fluid. At the time of this writing, one currently available pump is equipped with an integrated glucose sensor (see Figure 3). This device monitors interstitial fluid glucose levels continuously and can provide trend data, letting the user know whether blood sugars are rising or falling and how rapidly.25

Recently, researchers for the Sensor-Augmented Pump Therapy for A1C Reduction (STAR 3) study26,27 reported that use of sensor-augmented insulin pumps (SAP) reduces A1C without increasing hypoglycemia, compared with MDI insulin regimens. Additional markers of success in SAP use, compared with an MDI regimen, are sensor glucose values that are closer to target, bolus-calculator interactions, amount of sensor use, and lower glycemic variability—especially in patients who achieve lower A1C.28,29

Even when the patient is using a glucose sensor, however, blood sugars must still be tested at least twice a day to calibrate the sensor. There is a common misperception that CGM serves as a substitute for blood glucose (finger-stick) monitoring, but there is a lag time between interstitial fluid glucose levels and blood glucose levels.30 Blood glucose monitoring by finger-stick is still considered the gold standard for measuring glucose; sensor manufacturers recommend that patients not take a treatment action based on sensor data without confirming first with a finger-stick.

Barriers to effective glucose sensor use include the high cost of sensors and variability in insurance coverage, user factors (patients’ not using sensors daily, calibrating them inaccurately), insertion-site infections, and technology issues, like sensor failure.27,31

Memory Features

Pump technology makes it possible to review bolus history (ie, the amount of bolus and the time at which it was given) as well as the dosage of insulin taken throughout the day. Based on these data, several assessments can be made:

• Is the basal-to-bolus ratio appropriate? (It should be about 40% to 50% basal / 50% to 60% bolus.)8

• Is the amount of insulin adequate? Adults and prepubertal children with type 1 diabetes usually require 0.6 to 0.9 units/kg/d.15 During puberty, insulin requirements can rise to 1.5 units/kg/d32 due to increased insulin resistance, surges in pubertal hormones, and greater caloric intake during growth spurts. Pump manufacturers offer data management software that allows the user to produce graphs, track trends, and monitor basal-to-bolus ratios.