This illness is the most common cause of acquired heart disease in children in developed nations (with rheumatic fever remaining a more common cause in developing countries).1 The clinical features of KD are self-limited and will resolve even without appropriate therapy, but the patient can be left with significant coronary artery abnormalities.

A high index of clinical suspicion is needed to make a diagnosis of KD. Early diagnosis is critical because early treatment with IV gamma globulin can prevent coronary artery inflammation.2,3 Additionally, KD is potentially fatal; deaths continue to occur, even in the era of gamma globulin therapy.4 KD-associated mortality rates are fortunately very low—especially in Japan, where awareness of the illness is high, and diagnosis and treatment are usually prompt.5,6 Fatalities more commonly occur in children in whom the diagnosis is “missed,” not considered, or delayed.4Additionally, morbidity can be substantial in children who survive but are left with significant coronary artery abnormalities.7

KD has the highest incidence in children of Asian, particularly Japanese, descent: about 1 in 100 Japanese children develop KD by age 5 years.5Boys are more commonly affected than girls, at a ratio of 3 to 2.6 Also of note is that there is a 10-fold increased risk for KD in children with an affected sibling and a twofold increased risk for those with a previously affected parent.8,9 High incidence persists in Japanese children who have adopted a Western lifestyle10; thus, genetics are clearly a factor in KD incidence. However, KD occurs in all ethnic and racial groups worldwide. In areas with a low population of persons of Asian descent, most cases of KD occur in non-Asian children.11 In general, incidence in white children is one-tenth of that in Asian children, with an intermediate incidence in black and Hispanic children.

Clinical and epidemiologic features of KD strongly suggest an infectious cause, but no specific etiologic agent has yet been identified.12 The responsible agent could be a “new,” currently undiscovered virus.13

Patient Presentation and History

KD usually occurs in previously healthy children. Generally, the parent of a child with KD notices that the child seems more ill than is compatible with a typical viral illness. Though not included in the classic diagnostic criteria, marked irritability is very common in KD, particularly in infants. The history generally includes abrupt onset of fever that persists daily, with emergence of other KD signs and symptoms. On occasion, the parent will observe red eyes or a rash prior to fever onset.

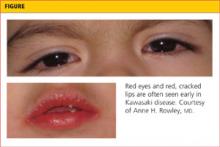

In KD, the known signs and symptoms of illness may not all be present simultaneously (see figure). If a child presents to the clinician on day 7 of fever and has red cracked lips, red, swollen hands and feet, and conjunctival injection, and the parent states that the child had a red rash from day 2 through day 5 of illness that is no longer present on examination, the history of rash can be useful in making a diagnosis of KD.14 Such a patient should be considered to have prolonged fever with physical examination revealing four of the five other known clinical features—fulfilling the classic diagnostic criteria for KD.

Criteria for Diagnosis of KD

KD is recognized to occur in two forms: classic and incomplete (“atypical”) cases. Children with classic cases have prolonged fever and at least four of the five clinical findings as described by the American Heart Association (AHA) Committee on Endocarditis, Rheumatic Fever, and Kawasaki Disease14 (see Table 1,14). Patients with incomplete cases have prolonged fever with fewer than four of the five known clinical findings.

Classic and incomplete cases share the same laboratory profile and pathologic features. At present, the development of coronary artery abnormalities is the only means by which a patient with an incomplete case can be confirmed to have had KD. However, because early treatment can reduce the prevalence of coronary artery abnormalities,2 timely diagnosis of either a classic or an incomplete case of KD is essential. Use of the AHA Committee algorithm14 can help the clinician make this diagnosis.

Classic KD

Fever

Fever in children with KD is generally high-spiking, usually reaching 39°C to 40°C daily, and intermittent, with fever usually occurring several times per day, and normal temperatures between fevers. Classic diagnostic criteria require that fever be present for at least five days, but KD can be diagnosed prior to the fifth day of illness by an experienced clinician. Duration of fever is the single best predictor of the development of coronary artery abnormalities,15 and temperatures should be carefully monitored, rectally or orally, in any child in whom a diagnosis of KD is being considered.

Oral Mucosal Changes

Erythema of the lips, mouth, and pharynx are common findings. The lips can be so dry and chapped that they bleed. Oral ulcerations are not a feature of KD, and pharyngeal exudate is not present. A “strawberry” tongue, with prominent papillae on an erythematous base, may be observed.14

Conjunctival Injection

Redness of the bulbar conjunctiva (involving the globe of the eye rather than the palpebral conjunctiva of the eyelid) is a notable feature that can persist for weeks in some patients. There is generally minimal to no exudate. Children with KD may experience light sensitivity, likely related to anterior uveitis, which can be a feature of KD.14

Changes in the Hands and Feet

Redness and swelling of the hands and feet can be clinically striking and quite painful for the child. As a result, children with KD who experience this development will often refuse to walk and may refuse to hold objects. These are unusual complaints in minor viral illnesses of childhood and should heighten the clinician’s suspicion for KD. Some children with KD have more noticeable involvement of the hands or the feet alone, but these extremity changes are bilateral. Swelling of only one hand or foot, for example, should raise suspicion for a bacterial infection, such as cellulitis, arthritis, or osteomyelitis, and reduce suspicion for KD.

Desquamation of the fingers and toes, beginning just beneath the nailbeds, is commonly observed in the subacute phase of KD, at about two to three weeks after onset of fever.14 Therefore, this finding is not useful in making a diagnosis of KD in the first week of illness—the optimal time for therapy to be initiated.

Rash

Rash in KD generally takes one of three forms. Most common is an erythematous, maculopapular rash on the trunk and extremities. Some children have a scarlatiniform rash on the trunk and extremities, prompting an initial concern for group A streptococcal infection. Other children with KD have erythema multiforme, with typical target lesions. Bullae and pustules are not observed in KD, although on rare occasions, a very fine micropustular rash can be observed.14

Of note, some children with KD have a significant rash in the groin area, which can be confused with candidal diaper dermatitis. This rash can occur in toilet-trained children as well as those still in diapers; it is often associated with desquamation of the affected skin, which is not typical of candidal dermatitis. In any child with prolonged fever and a desquamating erythematous groin rash, it is essential to make a careful examination for other features of KD.

Cervical Lymphadenopathy

This feature of KD is the least commonly observed, particularly in infants.16 In some older children, however, it is the most striking feature and can lead to a misdiagnosis of bacterial cervical adenitis.14 Children with this misdiagnosis are often treated with antibiotics with no response and delay of the correct diagnosis. Careful examination will usually reveal other clinical features of KD. Small lymph nodes are commonly palpated in the neck of young children; the lymph node should be > 1.5 cm in diameter to fulfill this criterion, according to the AHA Committee criteria for diagnosing KD.14 Lymphadenopathy, when present, tends to involve primarily the anterior cervical nodes overlying the sternocleidomastoid muscles.17

Incomplete KD

Patients with incomplete or “atypical” KD have fever with fewer than four of the other clinical findings. The term atypical does not indicate the presence of clinical findings that are not characteristic of KD. The AHA Committee14 recommends that a diagnosis of incomplete KD be considered in a child with fever for five days or longer with at least two other clinical features of KD, and with compatible laboratory and/or echocardiographic findings, as shown in Table 1.14

Laboratory Workup

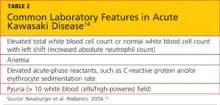

In the absence of a known pathologic cause of KD, no definitive diagnostic test exists. However, certain laboratory findings, shown in Table 214, are considered characteristic of the diagnosis. For example, a low peripheral white blood cell count with lymphocyte predominance is not considered a compatible laboratory profile for KD.

Generally, a complete blood count with differential, C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), liver function tests, and urinalysis are ordered. On diagnosis of KD, an echocardiogram should also be obtained to determine whether early coronary artery dilation is present, and to serve as a comparison for future studies.14,18

Diagnosis

In the presence of the previously described diagnostic criteria, a diagnosis of KD can be made. Patients with a presentation suggestive of incomplete KD should be treated for the illness if they have elevated CRP or ESR and other compatible laboratory or echocardiographic features shown in Table 1.14 In all children with a history of prolonged fever, rash and nonpurulent conjunctivitis—especially those younger than 1 year but including adolescents—KD should be included in the differential diagnosis.

Several other illnesses should be considered in the differential diagnosis of KD.

Measles, in an unimmunized or immigrant child, is a diagnosis that should be considered. In measles, rash usually begins on the face and behind the ears, then progresses to involve the entire body. In patients with measles in whom the rash has just appeared, Koplik spots (small white spots on the reddened oral mucosa near the molars) may be visible. Patients with measles have the classic triad of cough, coryza (rhinorrhea), and conjunctivitis; conjunctivitis is generally exudative.19

Scarlet fever should be considered, along with possible KD, in patients with a scarlatiniform rash. Because in some geographic areas 20% to 30% of children can be carriers of group A streptococcus, a positive throat culture could indicate acute infection or the carrier state.20 Treatment with penicillin for 24 hours generally clarifies the diagnosis; if the patient fails to improve on this therapy, KD should once again be considered.

Toxic shock syndrome can share some clinical features with severe KD, and patients with KD can experience shock.21 The presence of a staphylococcal or streptococcal focus of infection indicates toxic shock syndrome as the diagnosis, whereas the presence of coronary dilation on echocardiography points to KD.

Drug reactions can sometimes be confused with KD, and some patients with KD have a rash that may itch. The presence of facial and eyelid swelling is more likely to suggest a drug reaction than KD, and laboratory testing generally shows markedly elevated acute-phase reactants in KD,22 compared with those who are experiencing a drug reaction.

Viral illnesses, such as enterovirus infection, can share clinical features of KD, but usually will yield the elevated neutrophil count and acute-phase reactant elevations found in patients with KD.14,22 Children with adenovirus infection usually present with exudative pharyngitis and conjunctivitis.23

Once Diagnosis Is Confirmed

Patients in whom a diagnosis of KD is confirmed should be treated in a hospital where pediatric echocardiography is available, including measurement of coronary artery diameters in small children. In these patients, a Z score is calculated, representing standard deviations exceeding mean coronary artery dimensions, based on the patient’s body surface area. A child with a right proximal or left anterior descending coronary artery Z score greater than 2.5 (ie, 2.5 standard deviations above the mean) is confirmed to have an enlarged coronary artery.14,18

Echocardiography technicians must be well trained and experienced to be able to perform the necessary measurements, particularly in febrile, ill, uncooperative children. Only a pediatric cardiologist is qualified to interpret the studies.14

Treatment and Management

As soon as possible after a diagnosis of KD is made, patients should be treated with IV gamma globulin, 2 g/kg over 8 to 12 hours, and oral aspirin 80 to 100 mg/kg/d, divided for administration every 6 hours.3,14,24 High-dose aspirin is needed for its anti-inflammatory effect; its benefits for patients with KD appear to greatly outweigh the extremely low risk for Reye syndrome associated with aspirin use. In the rare patient with KD who has concurrent, documented influenza or varicella (and thus an increased risk for Reye syndrome with aspirin use), aspirin should be withheld, and an expert in KD should be consulted.

Most patients with KD respond rapidly to this therapeutic approach, with resolution of fever and improvement in clinical signs within 24 to 48 hours. However, 15% to 20% of patients do not respond to this initial treatment.14,25 The optimal therapy for such patients is unknown, but a second 2 g/kg dose of IV gamma globulin, IV methylprednisolone 30 mg/kg for 1 to 3 days, or IV infliximab 5 mg/kg are additional options.25-28

Patients who still do not respond may require additional therapies (eg, steroid therapy, infliximab, perhaps other immunosuppressive therapies), as these children are at high risk for coronary artery abnormalities. Referral of such patients to a center with extensive experience in caring for patients with KD should be considered.

Classic treatment studies have demonstrated a reduction in the prevalence of coronary artery abnormalities two months after illness onset from 18% in patients who were treated with aspirin alone to 4% in those who received IV gamma globulin and aspirin.24 However, more recent research, using newer algorithms to calculate normal coronary artery size based on body surface area, reveals that coronary artery dilation is more common in KD than previously recognized.2 Specifically, about 18% of patients with KD who present within the first 10 days of fever onset have already experienced some degree of coronary artery dilation before therapy is initiated. This highlights the importance of earlier diagnosis and treatment.

On the 14th day after fever onset (or 2 to 3 days after fever has resolved), aspirin is reduced to a single daily dose of 3 to 5 mg/kg.14 Aspirin use is continued for its antithrombotic effect until the ESR has normalized, provided echocardiography results have remained normal throughout. Aspirin therapy may be required indefinitely in patients who develop coronary artery aneurysms; in severe cases, additional antiplatelet or antithrombotic therapies may be required to prevent aneurysmal thrombosis.

Patient Education

A diagnosis of KD can be frightening. In the United States, most parents of a child diagnosed with KD have never heard of the condition and will need education and support. Once the child has been discharged and the parents discuss the illness with friends and acquaintances, they generally become aware that other children they know have had KD. The illness is not rare, but the public is generally unfamiliar with it.

Parents can be referred to the Web sites of the American Heart Association (www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/More/CardiovascularConditionsof Childhood/Kawasaki-Disease_UCM_308777_Article.jsp) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (see www.healthychildren.org), where educational materials about KD are posted. In the US, the Kawasaki Disease Foundation (http://www.kdfoundation.org/) also provides information and support to families with children affected by KD.

Follow-Up

Children with KD should undergo echocardiography at diagnosis, at 2 to 3 weeks, and again at 6 to 8 weeks after fever onset.14 At that point, a child with KD who has developed no evidence of coronary artery abnormalities will require no additional echocardiograms, as no evidence of late-onset, KD-associated coronary artery dilation has been reported.14,29 Children who have developed coronary artery dilation, however, will require further studies, as recommended by their pediatric cardiologist.

Laboratory testing should be performed at diagnosis, and acute-phase reactants (eg, CRP) should be monitored after discharge until normal levels are reached. Follow-up visits (often scheduled at 2 to 3 weeks and 6 to 8 weeks after illness onset) should consist of physical examination and laboratory testing, generally including a complete blood count and CRP level. This value often normalizes within 2 to 3 weeks after illness onset and can be helpful in monitoring clinical response, particularly in patients with persistent fever who require continuing therapy. Because the ESR rises transiently after IV gamma globulin therapy,30 it is not considered useful in monitoring response to therapy; the ESR usually normalizes by 6 to 8 weeks after fever onset.

Conclusion

KD is a potentially life-threatening illness of early childhood that should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any child with prolonged, unexplained fever. In KD, fever, rash, conjunctival injection, oral mucosal changes, extremity changes, and cervical adenopathy are self-limited, but any resulting coronary artery dilation and aneurysms can persist lifelong.

A high index of clinical suspicion is required to make a diagnosis of KD. Children with incomplete KD may present with fever and fewer than four other known clinical features; these children must undergo laboratory and echocardiographic studies for a diagnosis to be confirmed. Early diagnosis is essential for effective therapy with IV gamma globulin and aspirin to be administered before KD-associated coronary artery abnormalities can develop.

Additional research is needed to identify the cause of the disease, making it possible to develop a specific diagnostic test and etiology-targeted therapy.

References

1. Taubert KA, Rowley AH, Shulman ST. Seven-year national survey of Kawasaki disease and acute rheumatic fever. Pediatr Infect Dis J.1994;13(8):704-708.

2. Dominguez SR, Anderson MS, Eladawy M, Glodé MP. Preventing coronary artery abnormalities: a need for earlier diagnosis and treatment of Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012 Jul 3. [Epub ahead of print]

3. Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Beiser AS, et al. A single intravenous infusion of gamma globulin as compared with four infusions in the treatment of acute Kawasaki syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(23):1633-1639.

4. Orenstein JM, Shulman ST, Fox LM, et al. Three linked vasculopathic processes characterize Kawasaki disease: a light and transmission electron microscopic study. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e38998. Epub 2012 Jun 18.

5. Nakamura Y, Yashiro M, Uehara R, et al. Epidemiologic features of Kawasaki disease in Japan: results of the 2009-2010 nationwide survey. J Epidemiol. 2012;22(3):216-221.

6. Nakamura Y, Yanagawa H, Harada K, et al. Mortality among persons with a history of Kawasaki disease in Japan: the fifth look. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(2):162-165.

7. Suda K, Iemura M, Nishiono H, et al. Long-term prognosis of patients with Kawasaki disease complicated by giant coronary aneurysms: a single-institution experience. Circulation. 2011;123(17):1836-1842.

8. Fujita Y, Nakamura Y, Sakata K, et al. Kawasaki disease in families. Pediatrics. 1989;84(4):666-669.

9. Uehara R, Yashiro M, Nakamura Y, Yanagawa H. Kawasaki disease in parents and children. Acta Paediatr. 2003;92(6):694-697.

10. Dean AG, Melish ME, Hicks R, Palumbo NE. An epidemic of Kawasaki syndrome in Hawaii. J Pediatr. 1982;100(4):552-557.

11. Shulman ST, McAuley JB, Pachman LM, et al. Risk of coronary abnormalities due to Kawasaki disease in urban area with small Asian population. Am J Dis Child. 1987;141(4):420-425.

12. Rowley AH, Baker SC, Orenstein JM, Shulman ST. Searching for the cause of Kawasaki disease: cytoplasmic inclusion bodies provide new insight. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6(5):394-401.

13. Rowley AH, Baker SC, Shulman ST, et al. Ultrastructural, immunofluorescence, and RNA evidence support the hypothesis of a “new” virus associated with Kawasaki disease. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(7):1021-1030.

14. Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Gerber MA, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a statement for health professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association. Pediatrics. 2004;114(6):1708-1733.

15. Koren G, Lavi S, Rose V, Rowe R. Kawasaki disease: review of risk factors for coronary aneurysms. J Pediatr. 1986;108(3):388-392.

16. Sung RY, Ng YM, Choi KC, et al; Hong Kong Kawasaki Disease Study Group. Lack of association of cervical lymphadenopathy and coronary artery complications in Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25(6):521-525.

17. April MM, Burns JC, Newburger JW, Healy GB. Kawasaki disease and cervical adenopathy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;115:512.

18. Bratincsak A, Reddy VD, Purohit PJ, et al. Coronary artery dilation in acute Kawasaki disease and acute illnesses associated with fever.Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(9):924-926.

19. CDC. Hospital-associated measles outbreak: Pennsylvania, March – April 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(2):30-32.

20. Roberts AL, Connolly KL, Kirse DJ, et al. Detection of group A Streptococcus in tonsils from pediatric patients reveals high rate of asymptomatic streptococcal carriage. BMC Pediatr. 2012 Jan 9;12:3.

21. Dominguez SR, Friedman K, Seewalk R, et al. Kawasaki disease in a pediatric intensive care unit: a case-control study. Pediatrics.2008;122(4):e786-e790.

22. Huang MY, Gupta-Malhotra M, Huang JJ, et al. Acute-phase reactants and a supplemental diagnostic aid for Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 2010;31(8):1209-1213.

23. Singh-Naz N, Rodriguez W. Adenoviral infections in children. Adv Pediatr Infect Dis. 1996;11:365-388.

24. Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Burns JC, et al. The treatment of Kawasaki syndrome with intravenous gamma globulin. N Engl J Med.1986;315(6):341-347.

25. Son MB, Gauvreau K, Ma L, et al. Treatment of Kawasaki disease: analysis of 27 US pediatric hospitals from 2001 to 2007. Pediatrics.2009;124(1):1-8.

26. Chiyonobu T, Yoshihara T, Mori K, et al. Early intravenous gamma globulin retreatment for refractory Kawasaki disease. Clin Pediatr (Phila).2003;42(3):269-272.

27. Shah I, Prabhu SS. Response of refractory Kawasaki disease to intravenous methylprednisolone. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2009;29(1):51-53.

28. Blaisdell LL, Hayman JA, Moran. Infliximab treatment for pediatric refractory Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 2011;32(7):1023-1027.

29. Senzaki H. Long-term outcome of Kawasaki disease. Circulation. 2008;118(25);2763-2772.

30. Lee KY, Lee HS, Hong JH, et al. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulin downregulates the activated levels of inflammatory indices except erythrocyte sedimentation rate in acute stage of Kawasaki disease. J Trop Pediatr. 2005;51(2):98-101.