With a prevalence >17%, depression is one of the most common mental disorders in the United States and the second leading cause of disability worldwide.1,2 For decades, primary care and mental health providers have used selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) as first-line treatment for depression—yet the remission rate after the first trial of an antidepressant is <30%, and continues to decline after a first antidepressant failure.3

That is why clinicians continue to seek effective treatments for depression—ones that will provide quick and sustainable remission—and why scientists and pharmaceutical manufacturers have been competing to develop more effective antidepressant medications.

In the past 4 years, the FDA has approved 3 antidepressants—vilazodone, levomilnacipran, and vortioxetine—with the hope of increasing options for patients who suffer from major depression. These 3 antidepressants differ in their mechanisms of action from other available antidepressants, and all have been shown to have acceptable safety and tolerability profiles.

In this article, we review these novel antidepressants and present some clinical pearls for their use. We also present our observations that each agent appears to show particular advantage in a certain subpopulation of depressed patients who often do not respond, or who do not adequately respond, to other antidepressants.

Vilazodone

Vilazodone was approved by the FDA in 2011 (Table 1). The drug increases serotonin bioavailability in synapses through a strong dual action:

• blocking serotonin reuptake through the serotonin transporter

• partial agonism of the 5-HT1A presynaptic receptor.

Vilazodone also has a moderate effect on the 5-HT4 receptor and on dopamine and norepinephrine uptake inhibition.

The unique presynaptic 5-HT1A partial agonism of vilazodone is similar to that of buspirone, in which both drugs initially inhibit serotonin synthesis and neuronal firing.4 Researchers therefore expected that vilazodone would be more suitable for patients who have depression and a comorbid anxiety disorder; current FDA approval, however, is for depression only.

Adverse effects. The 5-HT4 receptor on which vilazodone acts is present in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and contributes to regulating symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)5; not surprisingly, the most frequent adverse effects of vilazodone are GI in nature (diarrhea, nausea, vomiting).

Headache is the most common non- GI side effect of vilazodone. Depressed patients who took vilazodone had no significant weight gain and did not report adverse sexual effects, compared with subjects given placebo.6

The following case—a patient with depression, significant anxiety, and IBS— exemplifies the type of patient for whom we find vilazodone most useful.

CASE Ms. A, age 19, is a college student with a history of major depressive disorder, social anxiety, and panic attacks for 2 years and IBS for 3 years. She was taking lubiprostone for IBS, with incomplete relief of GI symptoms. Because the family history included depression in Ms. A’s mother and sister, and both were doing well on escitalopram, we began a trial of that drug, 10 mg/d, that was quickly titrated to 20 mg/d.

Ms. A did not respond to 20 mg of escitalopram combined with psychotherapy.

We then started vilazodone, 10 mg/d after breakfast, for the first week, and reduced escitalopram to 10 mg/d. During Week 2, escitalopram was discontinued and vilazodone was increased to 20 mg/d. During Week 3, vilazodone was titrated to 40 mg/d.

Ms. A tolerated vilazodone well. Her depressive symptoms improved at the end of Week 2.

Unlike her experience with escitalopram, Ms. A’s anxiety symptoms—tenseness, racing thoughts, and panic attacks—all diminished when she switched to vilazodone. Notably, her IBS symptoms also were relieved, and she discontinued lubiprostone.

Ms. A’s depression remained in remission for 2 years, except for a brief period one summer, when she thought she “could do without any medication.” She tapered the vilazodone, week by week, to 10 mg/d, but her anxiety and bowel symptoms resurfaced to a degree that she resumed the 40-mg/d dosage.

Levomilnacipran

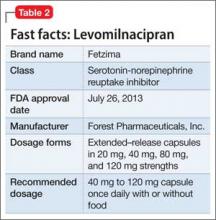

This drug is a 2013 addition to the small serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) family of venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, and duloxetine7 (Table 2). Levomilnacipran is the enantiomer of milnacipran, approved in Europe for depression but only for fibromyalgia pain and peripheral neuropathy in the United States.8 (Levomilnacipran is not FDA-approved for treating fibromyalgia pain.)

Levomilnacipran is unique because it is more of an NSRI, so to speak, than an SNRI: That is, the drug’s uptake inhibition of norepinephrine is more potent than its serotonin inhibition. Theoretically, levomilnacipran should help improve cognitive functions linked to the action of norepinephrine, such as concentration and motivation, and in turn, improve social function. The FDA also has approved levomilnacipran for treating functional impairment in depression.9

Adverse effects. The norepinephrine uptake inhibition of levomilnacipran might be responsible for observed increases in heart rate and blood pressure in some patients, and dose-dependent urinary hesitancy and erectile dysfunction in others. The drug has no significant effect on weight in depressed patients, compared with placebo.

Continue to: The benefits of levomilnacipran