User login

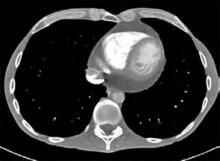

Patient history: A 40-year-old male with a history of anorexia, depression, and recent weight loss presents for a general medical evaluation prompted by his concerned father. A computed tomography (CT) scan of his chest shows a moderate amount of pneumomediastinum (PM) extending superiorly into the tissues of the neck. He also has a moderate-size pericardial effusion. The patient denies symptoms of chest pain, shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, or recreational drug use. Specifically, the patient admits to a depressed mood, but denies any vomiting, retching, or auto-destructive behavior. He has no history or evidence of underlying pulmonary disease.

Other notable findings consistent with the patient’s eating disorder are a body mass index (BMI) of 15, leukopenia, hyponatremia, bradycardia, and low blood pressure. A subsequent gastrograffin esophagram shows no obvious leaks or abnormalities. The patient is admitted to the hospital, allowed nothing by mouth, and placed on intravenous piperacillin and tazobactam, and nutrition. A transthoracic echocardiogram to evaluate the pericardial effusion on the first hospital day shows early tamponade physiology. Repeat evaluation two days later shows mild right atrial collapse but no evidence of hemodynamic compromise. Inpatient psychiatry consultation is obtained regarding his depression and eating disorder. On the fifth hospital day, a repeat CT scan shows moderate improvement of the PM. The patient is discharged home with outpatient follow-up.

Discussion: PM is defined as free air or gas in the mediastinum and is an uncommon finding. The etiology is usually from the airway, esophagus, or external trauma/surgery. Spontaneous PM occurs in the absence of an apparent identifiable cause and can exist in isolation or in conjunction with pneumothorax and soft-tissue emphysema. Elevated intraalveolar pressures related to mechanical ventilation or activities involving Valsalva maneuvers, along with pre-existing lung disease, account for the majority of pulmonary-related PM.1 Esophageal tear or rupture is another, less common cause of PM. Several case reports of PM in patients with anorexia nervosa exist, and some experts have postulated that one possible mechanism is vomiting or some other auto-destructive behavior.2-4 Loss of pulmonary connective tissue related to prolonged starvation leading to spontaneous pneumothorax and PM has also been postulated using rat models.5

The most common symptoms associated with PM are chest pain, voice change, and cough. In rare cases, PM can lead to decreased cardiac output. Common triggers of spontaneous PM, such as cough, physical exercise, and drug abuse, have been reported. A high percentage of patients with spontaneous PM have underlying pulmonary disease, including asthma and COPD.1 PM in conjunction with Boerhaave’s syndrome may have a mortality rate as high as 50% to 70%. In patients with anorexia nervosa, PM is often seen in conjunction with other advanced findings, including pancytopenia, electrolyte disturbances, bradycardia, and hypotension.

The age and gender of the patient are atypical for anorexia nervosa, although he does indeed have a restrictive eating disorder. The PM and pericardial effusion are additive unique findings that likely relate to his malnourished state and possible auto-destructive behavior.

Management: Spontaneous PM has been managed in a variety of ways, ranging from outpatient radiographic follow-up to close, inpatient monitoring. Identifying the etiology and monitoring for further progression or complications is important. For patients in whom esophageal tear or microperforation is suspected, early surgical consultation is recommended. An acceptable algorithm for patients with suspected esophageal perforation after endoscopy is to begin with a contrast CT scan of the neck and chest with oral contrast or to use a water-soluble contrast (gastrograffin) esophagram followed by a barium swallow if the water-soluble study is negative.6,7 When imaging reveals no leakage, the PM can be followed radiographically—typically after 48 hours and thereafter slowly advancing the diet. TH

Mackram Eleid, MD, works in the Division of Internal Medicine at the Mayo Clinic Arizona (Scottsdale/Phoenix). Joseph Charles, MD, FACP, is an assistant professor of Medicine and division education coordinator in the Mayo Clinic Hospital Arizona, Scottsdale/Phoenix.

References

- Campillo-Soto A, Coll-Salinas A, Soria-Aledo V, et al. [Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: descriptive study of our experience with 36 cases.] [in Spanish] Arch Bronconeumol. 2005;41:528-531.

- Danzer G, Mulzer J, Weber G, et al. Advanced anorexia nervosa, associated with pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, and soft-tissue emphysema without esophageal lesion. Int J Eat Disord. 2005 Nov;38(3):281-284.

- Brooks AP, Martyn C. Pneumomediastinum in anorexia nervosa. Br Med J. 1979;1:125.

- Chatfield WR, Bowditch JD, Forrest CA. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum complicating anorexia nervosa. Br Med J. 1979 Jan 13;1(6156):200-201.

- Sahebjami H, MacGee J. Changes in connective tissue composition of the lung in starvation and refeeding. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;128:644-647.

- Dodds WJ, Stewart ET, Vlymen WJ. Appropriate contrast media for the evaluation of esophageal disruption. Radiology. 1982 Jul;144(2):439-441.

- Ghahremani GG. Radiologic evaluation of suspected gastrointestinal perforations. Radiol Clin North Am. 1993 Nov;31(6):1219-1234.

Patient history: A 40-year-old male with a history of anorexia, depression, and recent weight loss presents for a general medical evaluation prompted by his concerned father. A computed tomography (CT) scan of his chest shows a moderate amount of pneumomediastinum (PM) extending superiorly into the tissues of the neck. He also has a moderate-size pericardial effusion. The patient denies symptoms of chest pain, shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, or recreational drug use. Specifically, the patient admits to a depressed mood, but denies any vomiting, retching, or auto-destructive behavior. He has no history or evidence of underlying pulmonary disease.

Other notable findings consistent with the patient’s eating disorder are a body mass index (BMI) of 15, leukopenia, hyponatremia, bradycardia, and low blood pressure. A subsequent gastrograffin esophagram shows no obvious leaks or abnormalities. The patient is admitted to the hospital, allowed nothing by mouth, and placed on intravenous piperacillin and tazobactam, and nutrition. A transthoracic echocardiogram to evaluate the pericardial effusion on the first hospital day shows early tamponade physiology. Repeat evaluation two days later shows mild right atrial collapse but no evidence of hemodynamic compromise. Inpatient psychiatry consultation is obtained regarding his depression and eating disorder. On the fifth hospital day, a repeat CT scan shows moderate improvement of the PM. The patient is discharged home with outpatient follow-up.

Discussion: PM is defined as free air or gas in the mediastinum and is an uncommon finding. The etiology is usually from the airway, esophagus, or external trauma/surgery. Spontaneous PM occurs in the absence of an apparent identifiable cause and can exist in isolation or in conjunction with pneumothorax and soft-tissue emphysema. Elevated intraalveolar pressures related to mechanical ventilation or activities involving Valsalva maneuvers, along with pre-existing lung disease, account for the majority of pulmonary-related PM.1 Esophageal tear or rupture is another, less common cause of PM. Several case reports of PM in patients with anorexia nervosa exist, and some experts have postulated that one possible mechanism is vomiting or some other auto-destructive behavior.2-4 Loss of pulmonary connective tissue related to prolonged starvation leading to spontaneous pneumothorax and PM has also been postulated using rat models.5

The most common symptoms associated with PM are chest pain, voice change, and cough. In rare cases, PM can lead to decreased cardiac output. Common triggers of spontaneous PM, such as cough, physical exercise, and drug abuse, have been reported. A high percentage of patients with spontaneous PM have underlying pulmonary disease, including asthma and COPD.1 PM in conjunction with Boerhaave’s syndrome may have a mortality rate as high as 50% to 70%. In patients with anorexia nervosa, PM is often seen in conjunction with other advanced findings, including pancytopenia, electrolyte disturbances, bradycardia, and hypotension.

The age and gender of the patient are atypical for anorexia nervosa, although he does indeed have a restrictive eating disorder. The PM and pericardial effusion are additive unique findings that likely relate to his malnourished state and possible auto-destructive behavior.

Management: Spontaneous PM has been managed in a variety of ways, ranging from outpatient radiographic follow-up to close, inpatient monitoring. Identifying the etiology and monitoring for further progression or complications is important. For patients in whom esophageal tear or microperforation is suspected, early surgical consultation is recommended. An acceptable algorithm for patients with suspected esophageal perforation after endoscopy is to begin with a contrast CT scan of the neck and chest with oral contrast or to use a water-soluble contrast (gastrograffin) esophagram followed by a barium swallow if the water-soluble study is negative.6,7 When imaging reveals no leakage, the PM can be followed radiographically—typically after 48 hours and thereafter slowly advancing the diet. TH

Mackram Eleid, MD, works in the Division of Internal Medicine at the Mayo Clinic Arizona (Scottsdale/Phoenix). Joseph Charles, MD, FACP, is an assistant professor of Medicine and division education coordinator in the Mayo Clinic Hospital Arizona, Scottsdale/Phoenix.

References

- Campillo-Soto A, Coll-Salinas A, Soria-Aledo V, et al. [Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: descriptive study of our experience with 36 cases.] [in Spanish] Arch Bronconeumol. 2005;41:528-531.

- Danzer G, Mulzer J, Weber G, et al. Advanced anorexia nervosa, associated with pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, and soft-tissue emphysema without esophageal lesion. Int J Eat Disord. 2005 Nov;38(3):281-284.

- Brooks AP, Martyn C. Pneumomediastinum in anorexia nervosa. Br Med J. 1979;1:125.

- Chatfield WR, Bowditch JD, Forrest CA. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum complicating anorexia nervosa. Br Med J. 1979 Jan 13;1(6156):200-201.

- Sahebjami H, MacGee J. Changes in connective tissue composition of the lung in starvation and refeeding. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;128:644-647.

- Dodds WJ, Stewart ET, Vlymen WJ. Appropriate contrast media for the evaluation of esophageal disruption. Radiology. 1982 Jul;144(2):439-441.

- Ghahremani GG. Radiologic evaluation of suspected gastrointestinal perforations. Radiol Clin North Am. 1993 Nov;31(6):1219-1234.

Patient history: A 40-year-old male with a history of anorexia, depression, and recent weight loss presents for a general medical evaluation prompted by his concerned father. A computed tomography (CT) scan of his chest shows a moderate amount of pneumomediastinum (PM) extending superiorly into the tissues of the neck. He also has a moderate-size pericardial effusion. The patient denies symptoms of chest pain, shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, or recreational drug use. Specifically, the patient admits to a depressed mood, but denies any vomiting, retching, or auto-destructive behavior. He has no history or evidence of underlying pulmonary disease.

Other notable findings consistent with the patient’s eating disorder are a body mass index (BMI) of 15, leukopenia, hyponatremia, bradycardia, and low blood pressure. A subsequent gastrograffin esophagram shows no obvious leaks or abnormalities. The patient is admitted to the hospital, allowed nothing by mouth, and placed on intravenous piperacillin and tazobactam, and nutrition. A transthoracic echocardiogram to evaluate the pericardial effusion on the first hospital day shows early tamponade physiology. Repeat evaluation two days later shows mild right atrial collapse but no evidence of hemodynamic compromise. Inpatient psychiatry consultation is obtained regarding his depression and eating disorder. On the fifth hospital day, a repeat CT scan shows moderate improvement of the PM. The patient is discharged home with outpatient follow-up.

Discussion: PM is defined as free air or gas in the mediastinum and is an uncommon finding. The etiology is usually from the airway, esophagus, or external trauma/surgery. Spontaneous PM occurs in the absence of an apparent identifiable cause and can exist in isolation or in conjunction with pneumothorax and soft-tissue emphysema. Elevated intraalveolar pressures related to mechanical ventilation or activities involving Valsalva maneuvers, along with pre-existing lung disease, account for the majority of pulmonary-related PM.1 Esophageal tear or rupture is another, less common cause of PM. Several case reports of PM in patients with anorexia nervosa exist, and some experts have postulated that one possible mechanism is vomiting or some other auto-destructive behavior.2-4 Loss of pulmonary connective tissue related to prolonged starvation leading to spontaneous pneumothorax and PM has also been postulated using rat models.5

The most common symptoms associated with PM are chest pain, voice change, and cough. In rare cases, PM can lead to decreased cardiac output. Common triggers of spontaneous PM, such as cough, physical exercise, and drug abuse, have been reported. A high percentage of patients with spontaneous PM have underlying pulmonary disease, including asthma and COPD.1 PM in conjunction with Boerhaave’s syndrome may have a mortality rate as high as 50% to 70%. In patients with anorexia nervosa, PM is often seen in conjunction with other advanced findings, including pancytopenia, electrolyte disturbances, bradycardia, and hypotension.

The age and gender of the patient are atypical for anorexia nervosa, although he does indeed have a restrictive eating disorder. The PM and pericardial effusion are additive unique findings that likely relate to his malnourished state and possible auto-destructive behavior.

Management: Spontaneous PM has been managed in a variety of ways, ranging from outpatient radiographic follow-up to close, inpatient monitoring. Identifying the etiology and monitoring for further progression or complications is important. For patients in whom esophageal tear or microperforation is suspected, early surgical consultation is recommended. An acceptable algorithm for patients with suspected esophageal perforation after endoscopy is to begin with a contrast CT scan of the neck and chest with oral contrast or to use a water-soluble contrast (gastrograffin) esophagram followed by a barium swallow if the water-soluble study is negative.6,7 When imaging reveals no leakage, the PM can be followed radiographically—typically after 48 hours and thereafter slowly advancing the diet. TH

Mackram Eleid, MD, works in the Division of Internal Medicine at the Mayo Clinic Arizona (Scottsdale/Phoenix). Joseph Charles, MD, FACP, is an assistant professor of Medicine and division education coordinator in the Mayo Clinic Hospital Arizona, Scottsdale/Phoenix.

References

- Campillo-Soto A, Coll-Salinas A, Soria-Aledo V, et al. [Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: descriptive study of our experience with 36 cases.] [in Spanish] Arch Bronconeumol. 2005;41:528-531.

- Danzer G, Mulzer J, Weber G, et al. Advanced anorexia nervosa, associated with pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, and soft-tissue emphysema without esophageal lesion. Int J Eat Disord. 2005 Nov;38(3):281-284.

- Brooks AP, Martyn C. Pneumomediastinum in anorexia nervosa. Br Med J. 1979;1:125.

- Chatfield WR, Bowditch JD, Forrest CA. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum complicating anorexia nervosa. Br Med J. 1979 Jan 13;1(6156):200-201.

- Sahebjami H, MacGee J. Changes in connective tissue composition of the lung in starvation and refeeding. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;128:644-647.

- Dodds WJ, Stewart ET, Vlymen WJ. Appropriate contrast media for the evaluation of esophageal disruption. Radiology. 1982 Jul;144(2):439-441.

- Ghahremani GG. Radiologic evaluation of suspected gastrointestinal perforations. Radiol Clin North Am. 1993 Nov;31(6):1219-1234.