Incidence and Characteristics

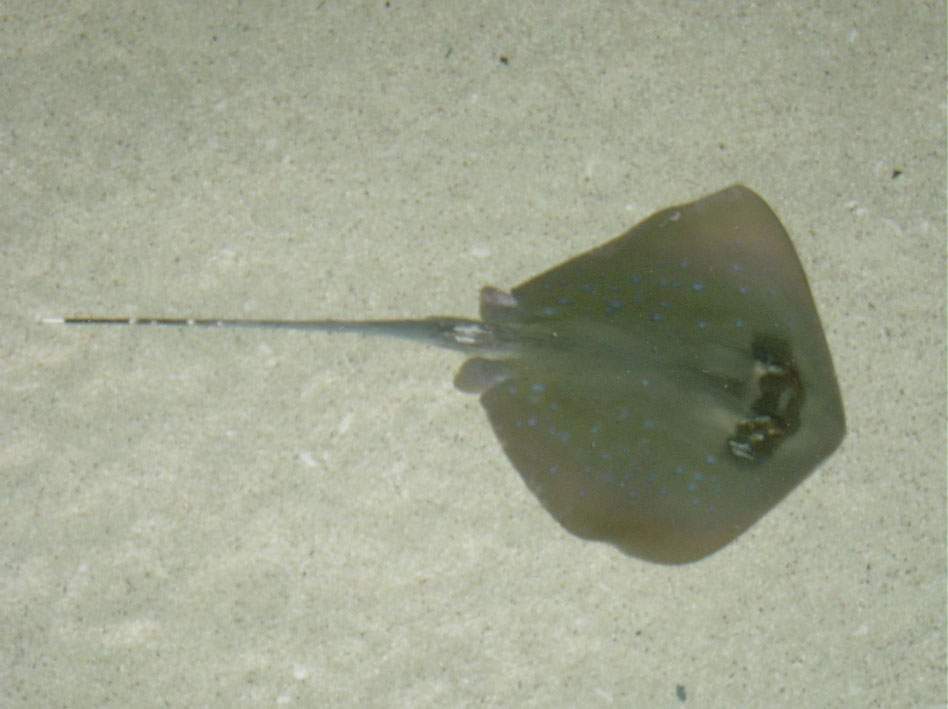

Stingrays are the most common cause of fish-related stings worldwide.1 The Urolophidae and Dasyatidae stingray families are responsible for most marine stingray injuries, including approximately 1500 reported injuries in the United States annually.1,2 Saltwater stingrays from these families commonly are encountered in shallow temperate and tropical coastal waters across the globe and possess dorsally and distally located spines capable of injuring humans that step on them (Figure 1).1,3 Freshwater stingrays (Potamotrygonidae family)(Figure 2) are not present in North America but rather inhabit lakes and river systems in South America, Africa, Laos, and Vietnam.4 Although recent incidence is unknown, Marinkelle5 estimated that thousands of stingray injuries occurred annually in the freshwater of Columbia during the 1960s. Unfortunately, the annual worldwide incidence of stingray injuries is generally unknown and is difficult to estimate, in part because injuries often go unreported.

Stingrays are dorsoventrally flattened, diamond-shaped fish with light-colored ventral and dark-colored dorsal surfaces. They have strong pectoral wings that allow them to swim forward and backward and even launch off waves.3 Stingrays range in size from the palm of a human hand to 6.5 ft in width. They possess 1 or more spines (2.5 to >30 cm in length) that are disguised by much longer tails.6,7 They often are encountered accidentally because they bury themselves in the sand or mud of shallow coastal waters or rivers with only their eyes and tails exposed to fool prey and avoid predators.

Injury Clinical Presentation

Stingray injuries typically involve the lower legs, ankles, or feet after stepping on a stingray.8 Fishermen can present with injuries of the upper extremities after handling fish with their hands.9 Other rarer injuries occur when individuals are swimming alongside stingrays or when stingrays catapult off waves into moving boats.10,11 Stingrays impale victims by using their tails to direct a retroserrate barb composed of a strong cartilaginous material called vasodentin. The barb releases venom by breaking through the venom-containing integumentary sheath that encapsulates it. Stingray venom contains phosphodiesterase, serotonin, and 5′-nucleotidase. It causes severe pain, vasoconstriction, ischemia, and poor wound healing, along with systemic effects such as disorientation, syncope, seizures, salivation, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, muscle cramps or fasciculations, pruritus, allergic reaction, hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, dyspnea, paralysis, and possibly death.1,8,12,13

Management

Pain Relief

As with many marine envenomations, immersion in hot but not scalding water can inactivate venom and reduce symptoms.8,9 In one retrospective review, 52 of 75 (69%) patients reporting to a California poison center with stingray injuries had improvement in pain within 1 hour of hot water immersion before any analgesics were instituted.8 In another review, 65 of 74 (88%) patients presenting to a California emergency department within 24 hours of sustaining a stingray injury had complete relief of pain within 30 minutes of hot water immersion. Patients who received analgesics in addition to hot water immersion did not require a second dose.9 In concordance with these studies, we suggest immersing areas affected by stingray injuries in hot water (temperature, 43.3°C to 46.1°C [110°F–115°F]; or as close to this range as tolerated) until pain subsides.8,9,14 Ice packs are an alternative to hot water immersion that may be more readily available to patients. If pain does not resolve following hot water immersion or application of an ice pack, additional analgesics and xylocaine without epinephrine may be helpful.9,15