User login

To the Editor:

Morphea, atrophoderma, guttate lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A), anetoderma, and their subtypes are inflammatory processes ultimately leading to dermal remodeling. We report a case of a scaly, hypopigmented, macular rash that clinically appeared as an entity along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum and demonstrated unique histopathologic changes in both collagen and elastin confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis. This case is a potentially rare variant representing a combination of clinical and microscopic findings.

A 29-year-old woman presented for an increasing number of white spots distributed on the trunk, arms, and legs. She denied local and systemic symptoms. The patient reported that she was stung by 100 wasps 23 years prior. Following the assault, her grandmother placed chewed tobacco leaves atop the painful erythematous wheals and flares. Upon resolution, hypopigmented macules and patches remained in their place. The patient denied associated symptoms or new lesions; she did not seek care at that time.

In her early 20s, the patient noted new, similarly distributed hypopigmented macules and patches without associated arthropod assault. She was treated by an outside dermatologist without result for presumed tinea versicolor. A follow-up superficial shave biopsy cited subtle psoriasiform dermatitis. Topical steroids did not improve the lesions. Her medical history also was remarkable for a reportedly unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear.

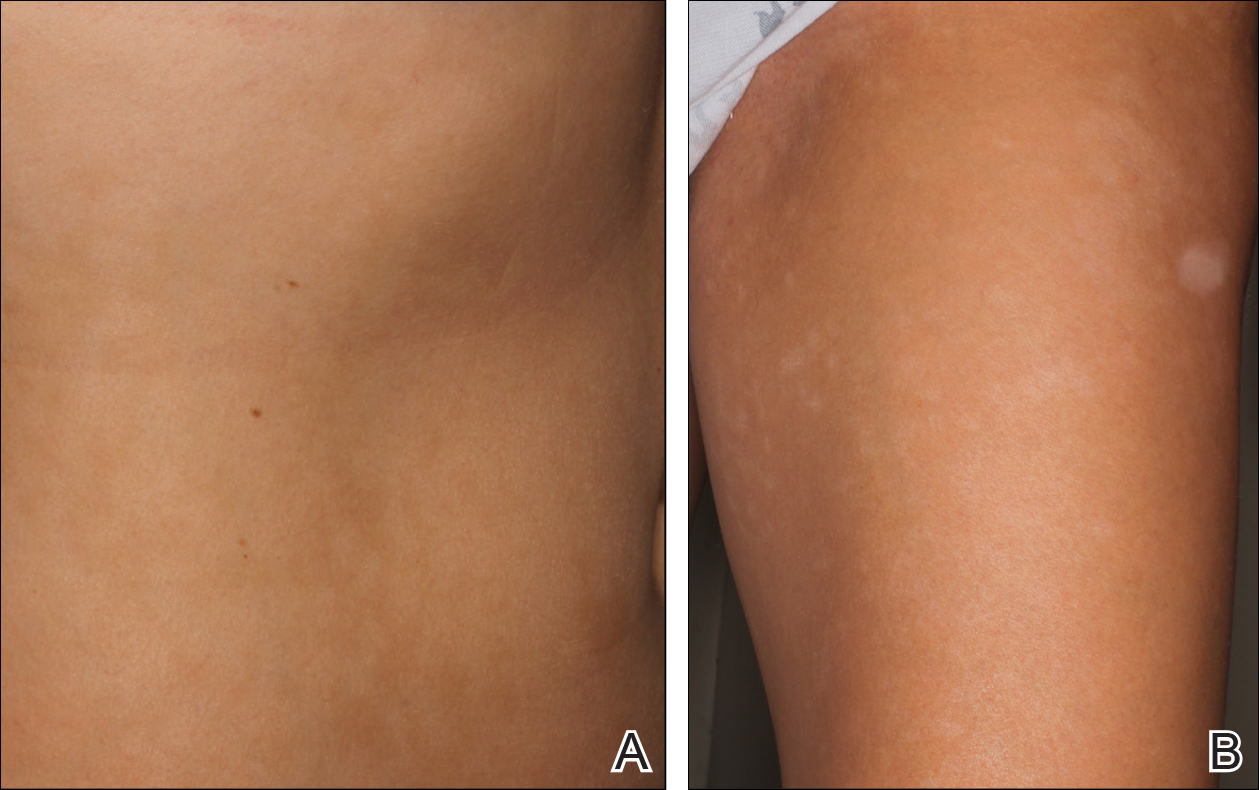

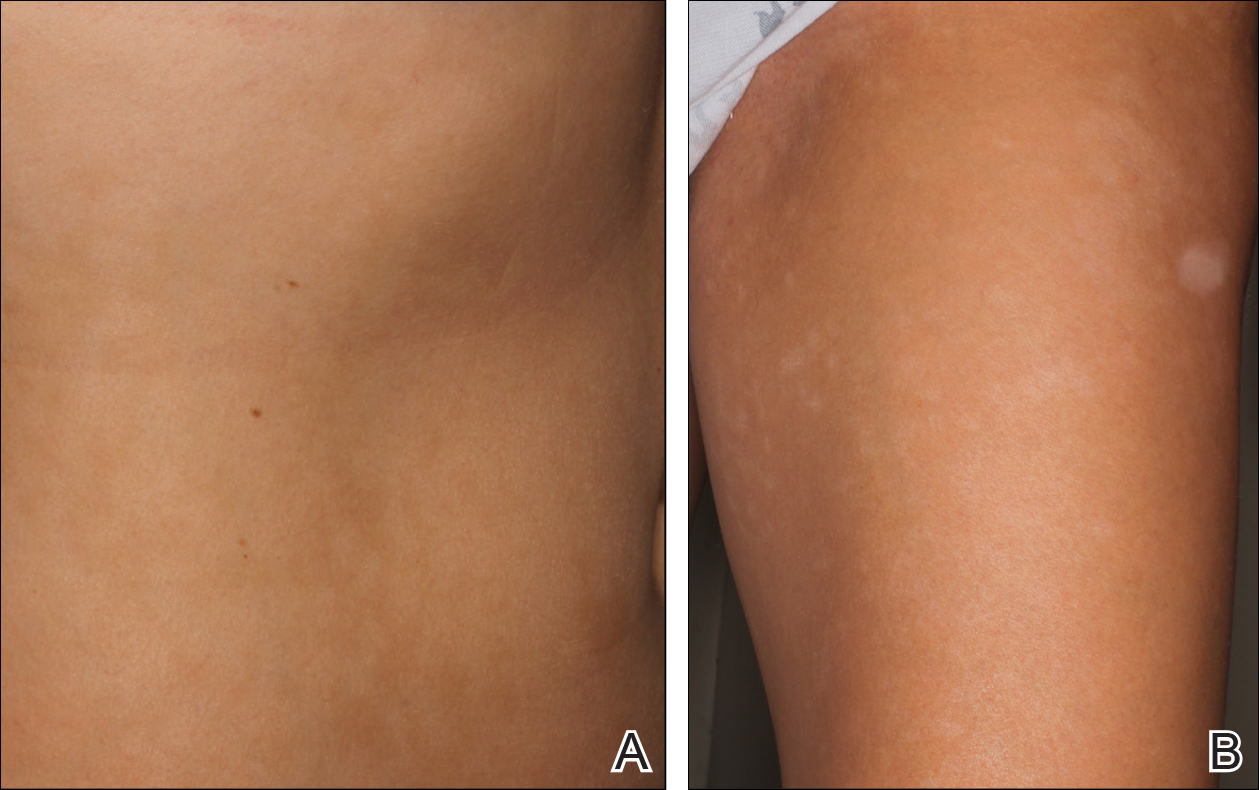

Physical examination revealed 0.5- to 2.0-cm, ill-defined, perifollicular and nonfollicular, slightly scaly macules and patches on the trunk, arms, and legs. There was no follicular plugging (Figure 1A). The hands, feet, face, and mucosal surfaces were spared. She had no family history of similar lesions. Although atrophic in appearance, a single lesion on the left thigh was palpably depressed (Figure 1B). Serology demonstrated a normal complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel, and negative Lyme titers. Light therapy and topical steroids failed to improve the lesions; calcipotriene cream 0.005% made the lesions erythematous and pruritic.

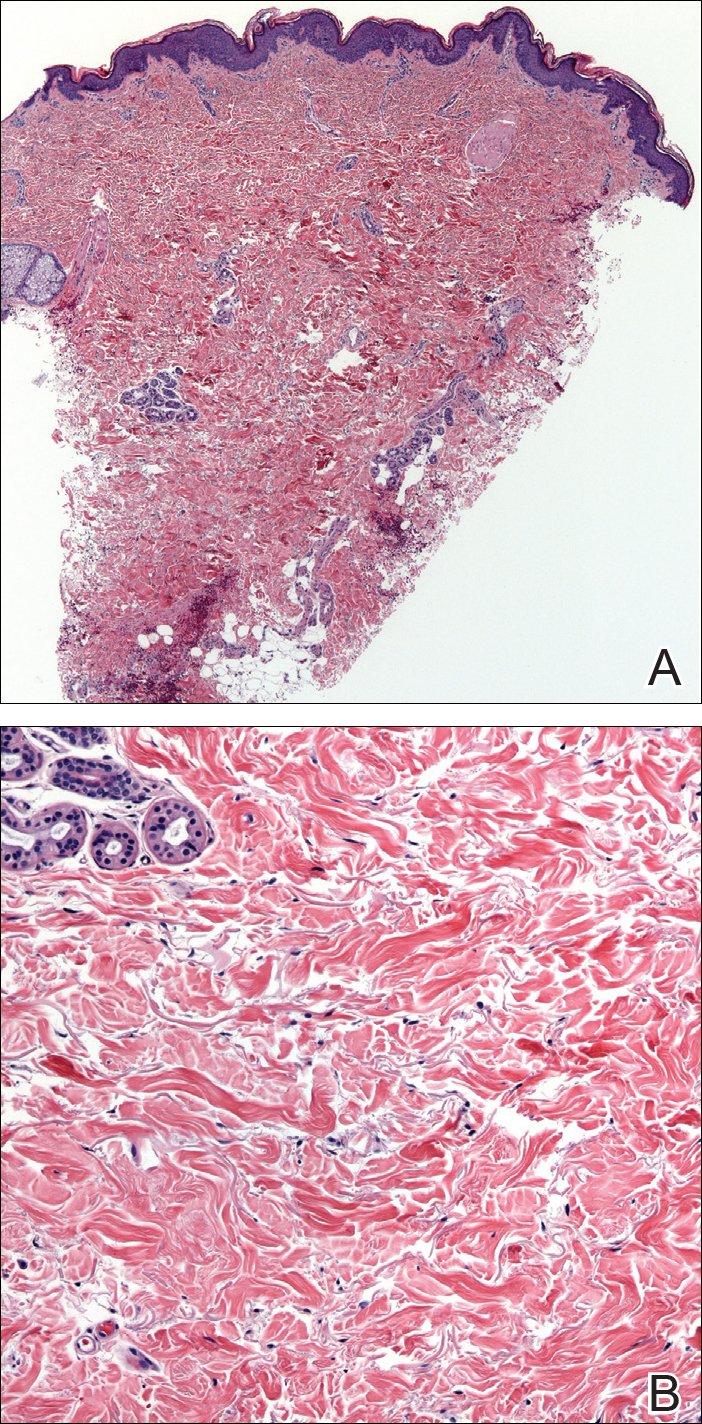

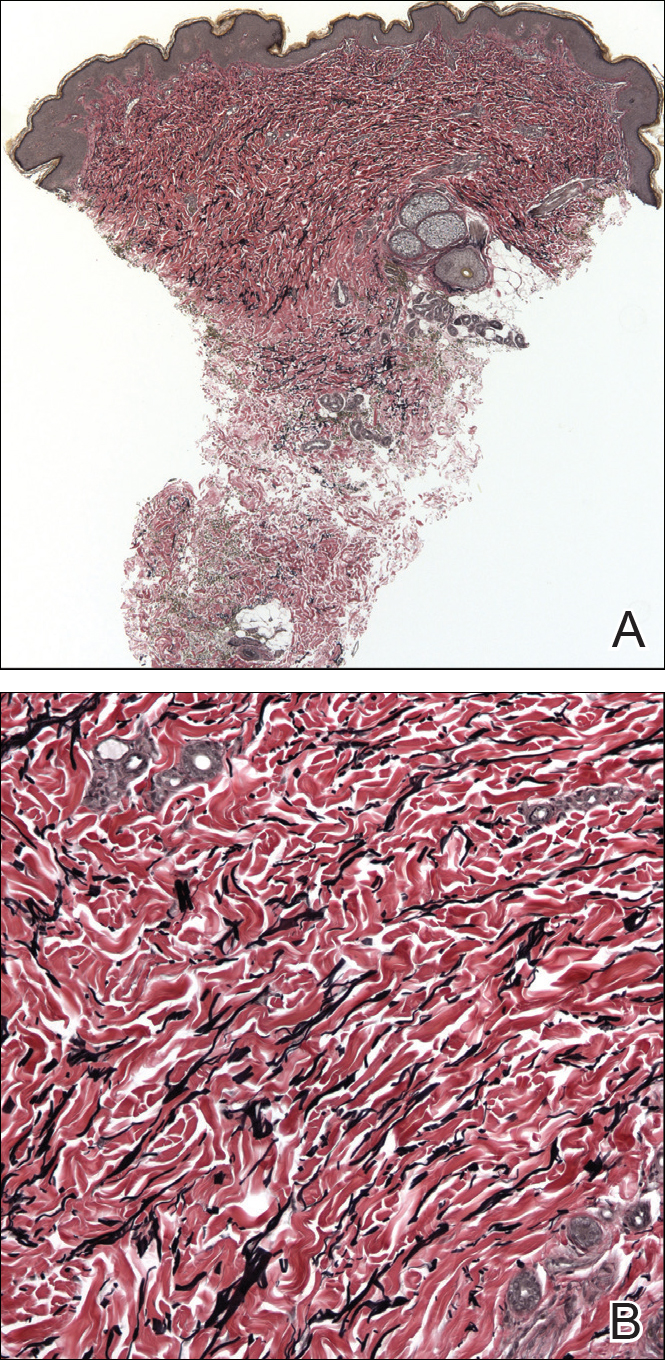

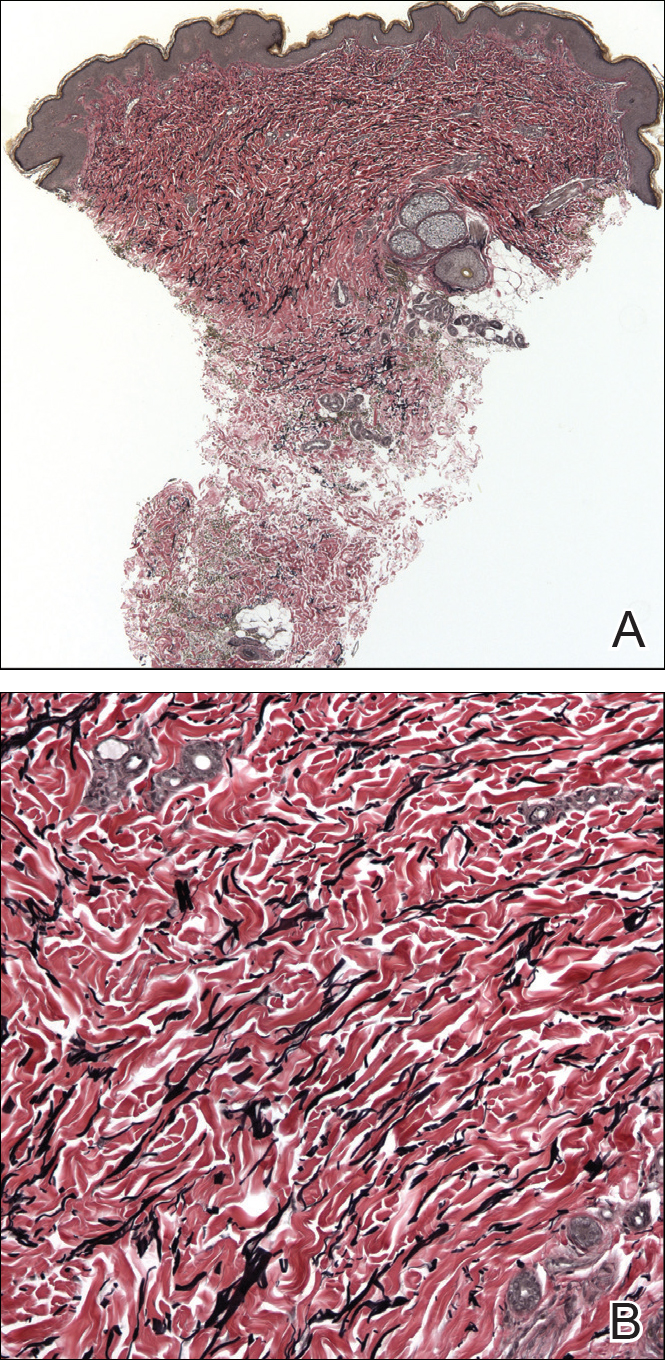

A biopsy from a flank lesion demonstrated a normal epithelium without thinning, a normal basal melanocyte population, and minimally effaced rete ridges. Thin collagen bundles were noted in the upper reticular and papillary dermis with associated fibroplasia (Figure 2). Verhoeff-van Gieson stain revealed decreased and fragmented elastin filaments in the same dermal distribution as the changed collagen (Figure 3). There was no evidence of primary inflammatory disease. The dermis was thinned. Periodic acid–Schiff stain confirmed the absence of hyphae and spores.

The relevant findings in our patient including the following: (1) onset of hypopigmented macules and patches following resolution of a toxic insult; (2) initially stable number of lesions that progressed in number but not size; (3) thinned collagen associated with fibroplasia in the upper reticular and papillary dermis; (4) decreased number and fragmentation of elastin filaments confined to the same region; (5) no congenital lesions or similar lesions in family members; and (6) a complete rotator cuff tear with no findings of a systemic connective-tissue disorder such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

We performed a literature search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using combinations of the terms atrophic, hypopigmented, white, spot disease, confetti-like, guttate, macules, atrophoderma, morphea, anetoderma, elastin, and collagen to identify potentially similar reports of guttate hypopigmented macules demonstrating changes of the collagen and elastin in the papillary and upper reticular dermis. Some variants, namely atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini (APP), guttate morphea, and superficial morphea, demonstrate similar clinical and histopathologic findings.

Findings similar to our case were documented in case reports of 2 women (aged 34 and 42 years)1 presenting with asymptomatic, atrophic, well-demarcated, shiny, hypopigmented macules over the trunk and upper extremities, which demonstrated a thinned epidermis with coarse hyalinized collagen bundles in the mid and lower dermis. There was upper and diffuse dermal elastolysis (patient 1 and patient 2, respectively).1 Our patient’s lesions were hypopigmented and atrophic in appearance but were slightly scaly and also involved the extremities. Distinct from these patient reports, histopathology from our case demonstrated thin packed collagen bundles and decreased fragmented elastin filaments confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis.

Plaque morphea is the most common type of localized scleroderma.2 The subtype APP demonstrates round to ovoid, gray-brown depressions with cliff-drop borders. They may appear flesh colored or hypopigmented.3,4 These sclerodermoid lesions lack the violaceous border classic to morphea. Sclerosis and induration also are typically absent.5 Clinically, our patient’s macules resembled this entity. Histopathologically, APP shows normal epithelium with an increased basal layer pigmentation; preserved adnexal structures; and mid to lower dermal collagen edema, clumping, and homogenization.3,4 Elastic fibers classically are unchanged, with exceptions.6-11 Changes in the collagen and elastin of our patient were unlike those reported in APP, which occur in the mid to lower dermis.

Guttate morphea demonstrates small, pale, minimally indurated, coin-shaped lesions on the trunk. Histopathology reveals less sclerosis and more edema, resembling LS&A.12 The earliest descriptions of this entity describe 3 stages: ivory/chalk white, scaly, and atrophic. Follicular plugging (absent in this patient) and fine scale can exist at any stage.13,14 Flattened rete ridges mark an otherwise preserved epidermis; hyalinized collagen typically is superficial and demonstrates less sclerosis yet increased edema.12-14 Fewer elastic fibers typically are present compared to normal skin. Changes seen in this entity are more superficial, as with our patient, than classic scleroderma. However, classic edema was not found in our patient’s biopsy specimen.

Superficial morphea, occurring predominantly in females, presents with hyperpigmented or hypopigmented patches having minimal to no induration. The lesions typically are asymptomatic. Histopathologically, collagen deposition and inflammation are confined to the superficial dermis without homogenization associated with LS&A, findings that were consistent with this patient’s biopsy.15,16 However, similar to other morpheaform variants, elastic fibers are unchanged.15 Verhoeff-van Gieson stain of the biopsy (Figure 3) showed the decreased and fragmented elastin network in the upper reticular and papillary dermis, making this entity less compatible.

Guttate LS&A may present with interfollicular, bluish white macules or papules coalescing into patches or plaques. Lesions evolve to reveal atrophic thin skin with follicular plugging. Histology demonstrates a thinned epidermis with orthohypokeratosis marked by flattened rete ridges. The dermis reveals short hyalinized collagen fibrils with a loss of elastic fibers in the papillary and upper reticular dermis, giving a homogenized appearance. Early disease is marked by an inflammatory infiltrate.17 Most of these findings are consistent with our patient’s pathology, which was confined to the upper dermis. Lacking, however, were characteristic findings of LS&A, including upper dermal homogenization, near-total effacement of rete ridges, orthokeratosis, and vacuolar degeneration at the dermoepidermal junction. As such, this entity is less compatible.

Atrophoderma elastolyticum discretum has clinical features of atrophoderma with elastolytic histopathologic findings.1 Anetoderma presents with outpouchings of atrophic skin with a surrounding ring of normal tissue. Histopathologically, this entity shows normal collagen with elastolysis; there also is a decrease in desmosine, an elastin cross-linker.1,3 Neither the clinical nor histopathologic findings in this patient matched these 2 entities.

The reported chronologic association of these lesions with an arthropod assault raised suspicion to their association with toxic insult or postinflammatory changes. One study reported mechanical trauma, including insect bites, as a possible inciting factor of morphea.11 These data, gathered from patient surveys, reported trauma associated to lesion development.1,17 A review of the literature regarding atrophoderma, morphea, and LS&A failed to identify pathogenic changes seen in this patient following initial trauma. Moreover, although it is difficult to prove causality in the formation of the original hypopigmented spots, the development of identical spots in a similar distribution without further trauma suggests against these etiologies to fully explain her lesions. Nonetheless, circumstance makes it difficult to prove whether the original arthropod insult spurred a smoldering reactive process that caused the newer lesions.

Hereditary connective-tissue disorders also were considered in the differential diagnosis. Because of the patient’s history of an unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome was considered; however, the remainder of her examination was normal, making a syndromic systemic disorder a less likely etiology.Because of the distinct clinical and histopathologic findings, this case may represent a rare and previously unreported variant of morphea. Clinically, these hypopigmented macules and patches exist somewhere along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum. Histopathologic findings do not conform to prior reports. The name atrophodermalike guttate morphea may be an appropriate appellation. It is possible this presentation represents a variant of what dermatologists have referred to as white spot disease.18 We hope that this case may bring others to discussion, allowing for the identification of a more precise entity and etiology so that patients may receive more directed therapy.

- Aksoy B, Ustün H, Gulbahce R, et al. Confetti-like macular atrophy: a new entity? J Dermatol. 2009;36:592-597.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Bauer EA, et al. Morphea and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. clinical and histopathologic studies in patients with combined features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:271-279.

- Buechner SA, Rufli T. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. clinical and histopathologic findings and antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi in thirty-four patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:441-446.

- Saleh Z, Abbas O, Dahdah MJ, et al. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini: a clinical and histopathological study. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1108-1114.

- Canizares O, Sachs PM, Jaimovich L, et al. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Arch Dermatol. 1958;77:42-58; discussion 58-60.

- Pullara TJ, Lober CW, Fenske NA. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:643-645.

- Jablonska S, Szczepanski A. Atrophoderma Pasini-Pierini: is it an entity? Dermatologica. 1962;125:226-242.

- Ang G, Hyde PM, Lee JB. Unilateral congenital linear atrophoderma of the leg. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:350-354.

- Miteva L, Kadurina M. Unilateral idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1391-1393.

- Kee CE, Brothers WS, New W. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini with coexistent morphea. a case report. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:100-103.

- Zulian F, Athreya BH, Laxer R, et al. Juvenile localized scleroderma: clinical and epidemiological features in 750 children. an international study. Rheumatology. 2006;45:614-620.

- Winkelmann RK. Localized cutaneous scleroderma. Semin Dermatol. 1985;4:90-103.

- Dore SE. Two cases of morphoea guttata. Proc R Soc Med. 1918;11:26-28.

- Dore SE. Guttate morphoea. Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:3-5.

- McNiff JM, Glusac EJ, Lazova RZ, et al. Morphea limited to the superficial reticular dermis: an underrecognized histologic phenomenon. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:315-319.

- Jacobson L, Palazij R, Jaworsky C. Superficial morphea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:323-325.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. London, England: Mosby Elsevier; 2007.

- Bunch JL. White-spot disease (morphoea guttata). Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:24-27.

To the Editor:

Morphea, atrophoderma, guttate lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A), anetoderma, and their subtypes are inflammatory processes ultimately leading to dermal remodeling. We report a case of a scaly, hypopigmented, macular rash that clinically appeared as an entity along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum and demonstrated unique histopathologic changes in both collagen and elastin confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis. This case is a potentially rare variant representing a combination of clinical and microscopic findings.

A 29-year-old woman presented for an increasing number of white spots distributed on the trunk, arms, and legs. She denied local and systemic symptoms. The patient reported that she was stung by 100 wasps 23 years prior. Following the assault, her grandmother placed chewed tobacco leaves atop the painful erythematous wheals and flares. Upon resolution, hypopigmented macules and patches remained in their place. The patient denied associated symptoms or new lesions; she did not seek care at that time.

In her early 20s, the patient noted new, similarly distributed hypopigmented macules and patches without associated arthropod assault. She was treated by an outside dermatologist without result for presumed tinea versicolor. A follow-up superficial shave biopsy cited subtle psoriasiform dermatitis. Topical steroids did not improve the lesions. Her medical history also was remarkable for a reportedly unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear.

Physical examination revealed 0.5- to 2.0-cm, ill-defined, perifollicular and nonfollicular, slightly scaly macules and patches on the trunk, arms, and legs. There was no follicular plugging (Figure 1A). The hands, feet, face, and mucosal surfaces were spared. She had no family history of similar lesions. Although atrophic in appearance, a single lesion on the left thigh was palpably depressed (Figure 1B). Serology demonstrated a normal complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel, and negative Lyme titers. Light therapy and topical steroids failed to improve the lesions; calcipotriene cream 0.005% made the lesions erythematous and pruritic.

A biopsy from a flank lesion demonstrated a normal epithelium without thinning, a normal basal melanocyte population, and minimally effaced rete ridges. Thin collagen bundles were noted in the upper reticular and papillary dermis with associated fibroplasia (Figure 2). Verhoeff-van Gieson stain revealed decreased and fragmented elastin filaments in the same dermal distribution as the changed collagen (Figure 3). There was no evidence of primary inflammatory disease. The dermis was thinned. Periodic acid–Schiff stain confirmed the absence of hyphae and spores.

The relevant findings in our patient including the following: (1) onset of hypopigmented macules and patches following resolution of a toxic insult; (2) initially stable number of lesions that progressed in number but not size; (3) thinned collagen associated with fibroplasia in the upper reticular and papillary dermis; (4) decreased number and fragmentation of elastin filaments confined to the same region; (5) no congenital lesions or similar lesions in family members; and (6) a complete rotator cuff tear with no findings of a systemic connective-tissue disorder such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

We performed a literature search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using combinations of the terms atrophic, hypopigmented, white, spot disease, confetti-like, guttate, macules, atrophoderma, morphea, anetoderma, elastin, and collagen to identify potentially similar reports of guttate hypopigmented macules demonstrating changes of the collagen and elastin in the papillary and upper reticular dermis. Some variants, namely atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini (APP), guttate morphea, and superficial morphea, demonstrate similar clinical and histopathologic findings.

Findings similar to our case were documented in case reports of 2 women (aged 34 and 42 years)1 presenting with asymptomatic, atrophic, well-demarcated, shiny, hypopigmented macules over the trunk and upper extremities, which demonstrated a thinned epidermis with coarse hyalinized collagen bundles in the mid and lower dermis. There was upper and diffuse dermal elastolysis (patient 1 and patient 2, respectively).1 Our patient’s lesions were hypopigmented and atrophic in appearance but were slightly scaly and also involved the extremities. Distinct from these patient reports, histopathology from our case demonstrated thin packed collagen bundles and decreased fragmented elastin filaments confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis.

Plaque morphea is the most common type of localized scleroderma.2 The subtype APP demonstrates round to ovoid, gray-brown depressions with cliff-drop borders. They may appear flesh colored or hypopigmented.3,4 These sclerodermoid lesions lack the violaceous border classic to morphea. Sclerosis and induration also are typically absent.5 Clinically, our patient’s macules resembled this entity. Histopathologically, APP shows normal epithelium with an increased basal layer pigmentation; preserved adnexal structures; and mid to lower dermal collagen edema, clumping, and homogenization.3,4 Elastic fibers classically are unchanged, with exceptions.6-11 Changes in the collagen and elastin of our patient were unlike those reported in APP, which occur in the mid to lower dermis.

Guttate morphea demonstrates small, pale, minimally indurated, coin-shaped lesions on the trunk. Histopathology reveals less sclerosis and more edema, resembling LS&A.12 The earliest descriptions of this entity describe 3 stages: ivory/chalk white, scaly, and atrophic. Follicular plugging (absent in this patient) and fine scale can exist at any stage.13,14 Flattened rete ridges mark an otherwise preserved epidermis; hyalinized collagen typically is superficial and demonstrates less sclerosis yet increased edema.12-14 Fewer elastic fibers typically are present compared to normal skin. Changes seen in this entity are more superficial, as with our patient, than classic scleroderma. However, classic edema was not found in our patient’s biopsy specimen.

Superficial morphea, occurring predominantly in females, presents with hyperpigmented or hypopigmented patches having minimal to no induration. The lesions typically are asymptomatic. Histopathologically, collagen deposition and inflammation are confined to the superficial dermis without homogenization associated with LS&A, findings that were consistent with this patient’s biopsy.15,16 However, similar to other morpheaform variants, elastic fibers are unchanged.15 Verhoeff-van Gieson stain of the biopsy (Figure 3) showed the decreased and fragmented elastin network in the upper reticular and papillary dermis, making this entity less compatible.

Guttate LS&A may present with interfollicular, bluish white macules or papules coalescing into patches or plaques. Lesions evolve to reveal atrophic thin skin with follicular plugging. Histology demonstrates a thinned epidermis with orthohypokeratosis marked by flattened rete ridges. The dermis reveals short hyalinized collagen fibrils with a loss of elastic fibers in the papillary and upper reticular dermis, giving a homogenized appearance. Early disease is marked by an inflammatory infiltrate.17 Most of these findings are consistent with our patient’s pathology, which was confined to the upper dermis. Lacking, however, were characteristic findings of LS&A, including upper dermal homogenization, near-total effacement of rete ridges, orthokeratosis, and vacuolar degeneration at the dermoepidermal junction. As such, this entity is less compatible.

Atrophoderma elastolyticum discretum has clinical features of atrophoderma with elastolytic histopathologic findings.1 Anetoderma presents with outpouchings of atrophic skin with a surrounding ring of normal tissue. Histopathologically, this entity shows normal collagen with elastolysis; there also is a decrease in desmosine, an elastin cross-linker.1,3 Neither the clinical nor histopathologic findings in this patient matched these 2 entities.

The reported chronologic association of these lesions with an arthropod assault raised suspicion to their association with toxic insult or postinflammatory changes. One study reported mechanical trauma, including insect bites, as a possible inciting factor of morphea.11 These data, gathered from patient surveys, reported trauma associated to lesion development.1,17 A review of the literature regarding atrophoderma, morphea, and LS&A failed to identify pathogenic changes seen in this patient following initial trauma. Moreover, although it is difficult to prove causality in the formation of the original hypopigmented spots, the development of identical spots in a similar distribution without further trauma suggests against these etiologies to fully explain her lesions. Nonetheless, circumstance makes it difficult to prove whether the original arthropod insult spurred a smoldering reactive process that caused the newer lesions.

Hereditary connective-tissue disorders also were considered in the differential diagnosis. Because of the patient’s history of an unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome was considered; however, the remainder of her examination was normal, making a syndromic systemic disorder a less likely etiology.Because of the distinct clinical and histopathologic findings, this case may represent a rare and previously unreported variant of morphea. Clinically, these hypopigmented macules and patches exist somewhere along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum. Histopathologic findings do not conform to prior reports. The name atrophodermalike guttate morphea may be an appropriate appellation. It is possible this presentation represents a variant of what dermatologists have referred to as white spot disease.18 We hope that this case may bring others to discussion, allowing for the identification of a more precise entity and etiology so that patients may receive more directed therapy.

To the Editor:

Morphea, atrophoderma, guttate lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A), anetoderma, and their subtypes are inflammatory processes ultimately leading to dermal remodeling. We report a case of a scaly, hypopigmented, macular rash that clinically appeared as an entity along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum and demonstrated unique histopathologic changes in both collagen and elastin confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis. This case is a potentially rare variant representing a combination of clinical and microscopic findings.

A 29-year-old woman presented for an increasing number of white spots distributed on the trunk, arms, and legs. She denied local and systemic symptoms. The patient reported that she was stung by 100 wasps 23 years prior. Following the assault, her grandmother placed chewed tobacco leaves atop the painful erythematous wheals and flares. Upon resolution, hypopigmented macules and patches remained in their place. The patient denied associated symptoms or new lesions; she did not seek care at that time.

In her early 20s, the patient noted new, similarly distributed hypopigmented macules and patches without associated arthropod assault. She was treated by an outside dermatologist without result for presumed tinea versicolor. A follow-up superficial shave biopsy cited subtle psoriasiform dermatitis. Topical steroids did not improve the lesions. Her medical history also was remarkable for a reportedly unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear.

Physical examination revealed 0.5- to 2.0-cm, ill-defined, perifollicular and nonfollicular, slightly scaly macules and patches on the trunk, arms, and legs. There was no follicular plugging (Figure 1A). The hands, feet, face, and mucosal surfaces were spared. She had no family history of similar lesions. Although atrophic in appearance, a single lesion on the left thigh was palpably depressed (Figure 1B). Serology demonstrated a normal complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel, and negative Lyme titers. Light therapy and topical steroids failed to improve the lesions; calcipotriene cream 0.005% made the lesions erythematous and pruritic.

A biopsy from a flank lesion demonstrated a normal epithelium without thinning, a normal basal melanocyte population, and minimally effaced rete ridges. Thin collagen bundles were noted in the upper reticular and papillary dermis with associated fibroplasia (Figure 2). Verhoeff-van Gieson stain revealed decreased and fragmented elastin filaments in the same dermal distribution as the changed collagen (Figure 3). There was no evidence of primary inflammatory disease. The dermis was thinned. Periodic acid–Schiff stain confirmed the absence of hyphae and spores.

The relevant findings in our patient including the following: (1) onset of hypopigmented macules and patches following resolution of a toxic insult; (2) initially stable number of lesions that progressed in number but not size; (3) thinned collagen associated with fibroplasia in the upper reticular and papillary dermis; (4) decreased number and fragmentation of elastin filaments confined to the same region; (5) no congenital lesions or similar lesions in family members; and (6) a complete rotator cuff tear with no findings of a systemic connective-tissue disorder such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

We performed a literature search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using combinations of the terms atrophic, hypopigmented, white, spot disease, confetti-like, guttate, macules, atrophoderma, morphea, anetoderma, elastin, and collagen to identify potentially similar reports of guttate hypopigmented macules demonstrating changes of the collagen and elastin in the papillary and upper reticular dermis. Some variants, namely atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini (APP), guttate morphea, and superficial morphea, demonstrate similar clinical and histopathologic findings.

Findings similar to our case were documented in case reports of 2 women (aged 34 and 42 years)1 presenting with asymptomatic, atrophic, well-demarcated, shiny, hypopigmented macules over the trunk and upper extremities, which demonstrated a thinned epidermis with coarse hyalinized collagen bundles in the mid and lower dermis. There was upper and diffuse dermal elastolysis (patient 1 and patient 2, respectively).1 Our patient’s lesions were hypopigmented and atrophic in appearance but were slightly scaly and also involved the extremities. Distinct from these patient reports, histopathology from our case demonstrated thin packed collagen bundles and decreased fragmented elastin filaments confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis.

Plaque morphea is the most common type of localized scleroderma.2 The subtype APP demonstrates round to ovoid, gray-brown depressions with cliff-drop borders. They may appear flesh colored or hypopigmented.3,4 These sclerodermoid lesions lack the violaceous border classic to morphea. Sclerosis and induration also are typically absent.5 Clinically, our patient’s macules resembled this entity. Histopathologically, APP shows normal epithelium with an increased basal layer pigmentation; preserved adnexal structures; and mid to lower dermal collagen edema, clumping, and homogenization.3,4 Elastic fibers classically are unchanged, with exceptions.6-11 Changes in the collagen and elastin of our patient were unlike those reported in APP, which occur in the mid to lower dermis.

Guttate morphea demonstrates small, pale, minimally indurated, coin-shaped lesions on the trunk. Histopathology reveals less sclerosis and more edema, resembling LS&A.12 The earliest descriptions of this entity describe 3 stages: ivory/chalk white, scaly, and atrophic. Follicular plugging (absent in this patient) and fine scale can exist at any stage.13,14 Flattened rete ridges mark an otherwise preserved epidermis; hyalinized collagen typically is superficial and demonstrates less sclerosis yet increased edema.12-14 Fewer elastic fibers typically are present compared to normal skin. Changes seen in this entity are more superficial, as with our patient, than classic scleroderma. However, classic edema was not found in our patient’s biopsy specimen.

Superficial morphea, occurring predominantly in females, presents with hyperpigmented or hypopigmented patches having minimal to no induration. The lesions typically are asymptomatic. Histopathologically, collagen deposition and inflammation are confined to the superficial dermis without homogenization associated with LS&A, findings that were consistent with this patient’s biopsy.15,16 However, similar to other morpheaform variants, elastic fibers are unchanged.15 Verhoeff-van Gieson stain of the biopsy (Figure 3) showed the decreased and fragmented elastin network in the upper reticular and papillary dermis, making this entity less compatible.

Guttate LS&A may present with interfollicular, bluish white macules or papules coalescing into patches or plaques. Lesions evolve to reveal atrophic thin skin with follicular plugging. Histology demonstrates a thinned epidermis with orthohypokeratosis marked by flattened rete ridges. The dermis reveals short hyalinized collagen fibrils with a loss of elastic fibers in the papillary and upper reticular dermis, giving a homogenized appearance. Early disease is marked by an inflammatory infiltrate.17 Most of these findings are consistent with our patient’s pathology, which was confined to the upper dermis. Lacking, however, were characteristic findings of LS&A, including upper dermal homogenization, near-total effacement of rete ridges, orthokeratosis, and vacuolar degeneration at the dermoepidermal junction. As such, this entity is less compatible.

Atrophoderma elastolyticum discretum has clinical features of atrophoderma with elastolytic histopathologic findings.1 Anetoderma presents with outpouchings of atrophic skin with a surrounding ring of normal tissue. Histopathologically, this entity shows normal collagen with elastolysis; there also is a decrease in desmosine, an elastin cross-linker.1,3 Neither the clinical nor histopathologic findings in this patient matched these 2 entities.

The reported chronologic association of these lesions with an arthropod assault raised suspicion to their association with toxic insult or postinflammatory changes. One study reported mechanical trauma, including insect bites, as a possible inciting factor of morphea.11 These data, gathered from patient surveys, reported trauma associated to lesion development.1,17 A review of the literature regarding atrophoderma, morphea, and LS&A failed to identify pathogenic changes seen in this patient following initial trauma. Moreover, although it is difficult to prove causality in the formation of the original hypopigmented spots, the development of identical spots in a similar distribution without further trauma suggests against these etiologies to fully explain her lesions. Nonetheless, circumstance makes it difficult to prove whether the original arthropod insult spurred a smoldering reactive process that caused the newer lesions.

Hereditary connective-tissue disorders also were considered in the differential diagnosis. Because of the patient’s history of an unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome was considered; however, the remainder of her examination was normal, making a syndromic systemic disorder a less likely etiology.Because of the distinct clinical and histopathologic findings, this case may represent a rare and previously unreported variant of morphea. Clinically, these hypopigmented macules and patches exist somewhere along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum. Histopathologic findings do not conform to prior reports. The name atrophodermalike guttate morphea may be an appropriate appellation. It is possible this presentation represents a variant of what dermatologists have referred to as white spot disease.18 We hope that this case may bring others to discussion, allowing for the identification of a more precise entity and etiology so that patients may receive more directed therapy.

- Aksoy B, Ustün H, Gulbahce R, et al. Confetti-like macular atrophy: a new entity? J Dermatol. 2009;36:592-597.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Bauer EA, et al. Morphea and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. clinical and histopathologic studies in patients with combined features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:271-279.

- Buechner SA, Rufli T. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. clinical and histopathologic findings and antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi in thirty-four patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:441-446.

- Saleh Z, Abbas O, Dahdah MJ, et al. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini: a clinical and histopathological study. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1108-1114.

- Canizares O, Sachs PM, Jaimovich L, et al. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Arch Dermatol. 1958;77:42-58; discussion 58-60.

- Pullara TJ, Lober CW, Fenske NA. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:643-645.

- Jablonska S, Szczepanski A. Atrophoderma Pasini-Pierini: is it an entity? Dermatologica. 1962;125:226-242.

- Ang G, Hyde PM, Lee JB. Unilateral congenital linear atrophoderma of the leg. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:350-354.

- Miteva L, Kadurina M. Unilateral idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1391-1393.

- Kee CE, Brothers WS, New W. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini with coexistent morphea. a case report. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:100-103.

- Zulian F, Athreya BH, Laxer R, et al. Juvenile localized scleroderma: clinical and epidemiological features in 750 children. an international study. Rheumatology. 2006;45:614-620.

- Winkelmann RK. Localized cutaneous scleroderma. Semin Dermatol. 1985;4:90-103.

- Dore SE. Two cases of morphoea guttata. Proc R Soc Med. 1918;11:26-28.

- Dore SE. Guttate morphoea. Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:3-5.

- McNiff JM, Glusac EJ, Lazova RZ, et al. Morphea limited to the superficial reticular dermis: an underrecognized histologic phenomenon. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:315-319.

- Jacobson L, Palazij R, Jaworsky C. Superficial morphea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:323-325.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. London, England: Mosby Elsevier; 2007.

- Bunch JL. White-spot disease (morphoea guttata). Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:24-27.

- Aksoy B, Ustün H, Gulbahce R, et al. Confetti-like macular atrophy: a new entity? J Dermatol. 2009;36:592-597.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Bauer EA, et al. Morphea and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. clinical and histopathologic studies in patients with combined features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:271-279.

- Buechner SA, Rufli T. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. clinical and histopathologic findings and antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi in thirty-four patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:441-446.

- Saleh Z, Abbas O, Dahdah MJ, et al. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini: a clinical and histopathological study. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1108-1114.

- Canizares O, Sachs PM, Jaimovich L, et al. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Arch Dermatol. 1958;77:42-58; discussion 58-60.

- Pullara TJ, Lober CW, Fenske NA. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:643-645.

- Jablonska S, Szczepanski A. Atrophoderma Pasini-Pierini: is it an entity? Dermatologica. 1962;125:226-242.

- Ang G, Hyde PM, Lee JB. Unilateral congenital linear atrophoderma of the leg. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:350-354.

- Miteva L, Kadurina M. Unilateral idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1391-1393.

- Kee CE, Brothers WS, New W. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini with coexistent morphea. a case report. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:100-103.

- Zulian F, Athreya BH, Laxer R, et al. Juvenile localized scleroderma: clinical and epidemiological features in 750 children. an international study. Rheumatology. 2006;45:614-620.

- Winkelmann RK. Localized cutaneous scleroderma. Semin Dermatol. 1985;4:90-103.

- Dore SE. Two cases of morphoea guttata. Proc R Soc Med. 1918;11:26-28.

- Dore SE. Guttate morphoea. Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:3-5.

- McNiff JM, Glusac EJ, Lazova RZ, et al. Morphea limited to the superficial reticular dermis: an underrecognized histologic phenomenon. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:315-319.

- Jacobson L, Palazij R, Jaworsky C. Superficial morphea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:323-325.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. London, England: Mosby Elsevier; 2007.

- Bunch JL. White-spot disease (morphoea guttata). Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:24-27.

Practice Points

- Atrophodermalike guttate morphea is a potentially underreported or undescribed entity consisting of a combination of clinicopathologic features.

- Widespread hypopigmented macules on the trunk and extremities marked by thinned collagen, fibroplasia, and altered fragmented elastin in the papillary dermis and upper reticular dermis are the key features.

- Atrophoderma, morphea, and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus should be ruled out during clinical workup.