User login

Eccrine Porocarcinoma Presenting as a Recurrent Wart

Eccrine porocarcinoma (EPC), originally described by Pinkus and Mehregan1 in 1963, is an exceedingly rare sweat gland tumor most commonly seen in older patients. Fewer than 300 cases have been reported in the literature, and it is believed to represent only 0.005% to 0.01% of cutaneous malignancies.2 In the absence of established guidelines, wide local excision (WLE) has traditionally been considered the standard of treatment; however, local recurrence and nodal metastasis rates associated with WLE have been reported as high as 20%.3 More recently, a number of case reports and small case series have demonstrated higher cure rates with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), though follow-up is limited.3-5 We describe a case of EPC presenting as a recurrent wart in a 36-year-old man that was successfully treated with MMS.

Case Report

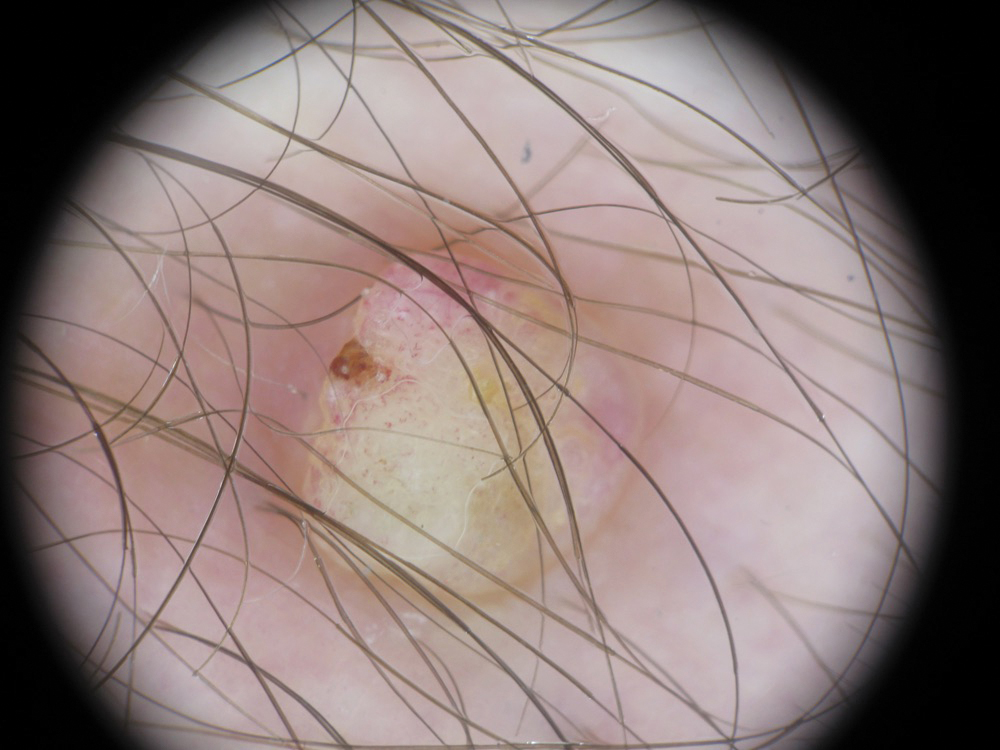

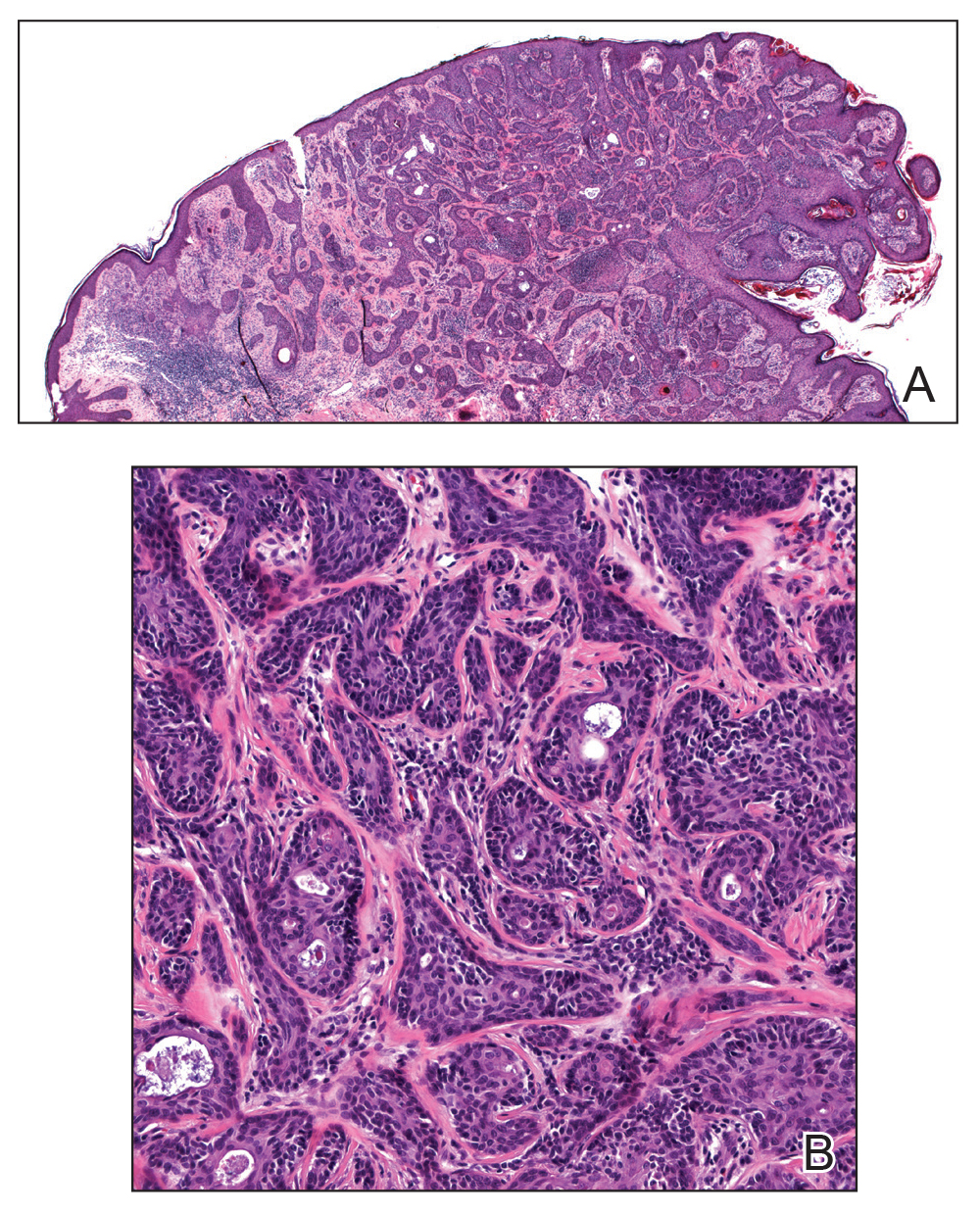

A 36-year-old man with no notable medical history presented with a 0.5×0.5-cm, asymptomatic, flesh-colored, hyperkeratotic, polypoid papule on the right medial thigh (Figure 1). The lesion was diagnosed as a wart and treated with cryotherapy by another dermatologist several years prior to presentation. Dermatoscopic examination at the current presentation showed a homogenous yellow center with a few peripheral vessels and a faint pink-tan halo (Figure 2). Our differential diagnosis included a recurrent wart, fibrosed pyogenic granuloma, irritated intradermal nevus, skin tag, and adnexal neoplasm. A shave biopsy was performed. Histopathologic analysis revealed multiple aggregations of mildly pleomorphic epithelial cells emanating from the epidermis, with many aggregations containing ductal structures (Figure 3). Rare necrotic and pyknotic cells were present, but no mitotic figures or lymphovascular invasion were identified. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen but negative for Ber-EP4. These findings were consistent with a well-differentiated EPC.

The patient was offered MMS or WLE, with or without sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB). He opted for MMS. The initial 1-cm margin taken during MMS was sufficient to achieve complete tumor extirpation, and the final 3.7×2.5-cm defect was closed primarily. The MMS debulking specimen was sent for permanent sectioning and showed a small focus of residual tumor cells, but no mitoses or lymphovascular invasion were seen. The patient was referred to surgical oncology to discuss the option of SLNB, which he ultimately declined. He also was offered regional or whole-body positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) to rule out metastatic disease, which he also declined. There was no evidence of recurrence or lymphadenopathy 19 months postoperatively.

Comment

Eccrine porocarcinoma is an exceptionally rare adnexal neoplasm that most commonly affects older adults. The average age at diagnosis is 71 years in men and 75 years in women.2 Our case is rare because of the patient’s age. Benign eccrine poromas occur most frequently on the palms, soles, axillae, and forehead where eccrine density is highest; EPC occurs most frequently on the lower extremities.6 It may arise de novo or from malignant transformation of a preexisting benign poroma. Clinically, EPC may present as an asymptomatic pink-brown papule, plaque, or nodule and may have a polypoid or verrucous appearance, as in our patient. Ulceration is common.7 The differential diagnosis often includes nodular basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, pyogenic granuloma, and seborrheic keratosis.

Histologically, EPCs are characterized by aggregations of cohesive basaloid epithelial cells forming eccrine ductal structures.2 Cellular atypia may be extremely subtle but, if present, can be helpful in differentiating malignant from benign lesions. Features of basal and squamous cell carcinoma also may be present. Definitive diagnosis is frequently based on the overall invasive architectural pattern.5 Robson et al2 examined 69 cases of EPC for high-risk histologic features and concluded that tumor depth greater than 7 mm, mitoses greater than 14 per high-power field, and the presence of lymphovascular invasion were independently predictive of mortality. Moreover, after adjusting for mitosis and depth, an infiltrative border vs a pushing border was strongly predictive of local recurrence.2 Immunohistochemical stains, although not necessary for diagnosis, may have utility as adjunctive tools. Cells lining the ducts within EPCs commonly stain positive for carcinoembryonic antigen, though glandular myoepithelial cells stain positive for S-100. Negative Ber-EP4 staining helps to differentiate EPC from basal cell carcinoma. Abnormal expression of p53 and overexpression of p16 also has been described.4

The rarity of EPC has precluded the development of any evidence-based management guidelines. Historically, the standard of care has been WLE with 2- to 3-cm margins. A review of 105 cases of EPC treated with WLE showed 20% local recurrence, 20% regional metastases, and 12% distant metastasis rates.8 Mohs micrographic surgery, which allows examination of 100% of the surgical margin vs less than 1% for WLE with the standard bread-loafing technique, might be expected to achieve higher cure rates. A review of 29 cases treated with MMS monotherapy demonstrated no local recurrences, distant metastasis, or disease-specific deaths with follow-up ranging from 19 months to 6 years.5 One case was associated with regional lymph node metastases that were treated with completion lymphadenectomy and adjuvant radiation therapy.7 The high mortality rate of patients with nodal disease has led some to recommend PET-CT and SLNB for patients with EPC. However, the prognostic value of such procedures has not been clearly defined and there is no demonstrated survival benefit for treatment of widespread disease. Our patient declined both SLNB and PET-CT, and our plan was to follow him clinically with symptom-directed imaging only.

Conclusion

Patients with EPC generally have a favorable prognosis with prompt diagnosis and complete surgical excision. Although most commonly seen in elderly patients, EPC may present in younger patients and may be clinically and histologically nondescript with little cytologic atypia. Based on a small but growing body of literature, MMS appears to be at least as effective as WLE as a primary treatment modality for EPC, while offering the advantage of tissue sparing in cosmetically or functionally important areas.

- Pinkus H, Mehregan AH. Epidermatropic eccrine carcinoma. a case combining eccrine poroma and Paget’s dermatoses. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:597-606.

- Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720.

- Tolkachjov SN, Hocker TL, Camilleri MJ, et al. Treatment of porocarcinoma with Mohs micrographic surgery: The Mayo Clinic Experience. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:745-750.

- Tidwell WJ, Mayer JE, Malone J, et al. Treatment of eccrine porocarcinoma with Mohs micrographic surgery: a cases series and literature review. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1078-1083.

- Xu YG, Aylward J, Longley BJ, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma treated by Mohs micrographic surgery: over 6-year follow-up of 12 cases and literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:685-692.

- D’Ambrosia RA, Ward H, Parry E. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the eyelid treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:4:570-571.

- Vleugels FR, Girouard SD, Schmults CD, et al. Metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma after Mohs micrographic surgery: a case report. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:188-191.

- Snow SN, Reizner GT. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the face. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:306-311.

Eccrine porocarcinoma (EPC), originally described by Pinkus and Mehregan1 in 1963, is an exceedingly rare sweat gland tumor most commonly seen in older patients. Fewer than 300 cases have been reported in the literature, and it is believed to represent only 0.005% to 0.01% of cutaneous malignancies.2 In the absence of established guidelines, wide local excision (WLE) has traditionally been considered the standard of treatment; however, local recurrence and nodal metastasis rates associated with WLE have been reported as high as 20%.3 More recently, a number of case reports and small case series have demonstrated higher cure rates with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), though follow-up is limited.3-5 We describe a case of EPC presenting as a recurrent wart in a 36-year-old man that was successfully treated with MMS.

Case Report

A 36-year-old man with no notable medical history presented with a 0.5×0.5-cm, asymptomatic, flesh-colored, hyperkeratotic, polypoid papule on the right medial thigh (Figure 1). The lesion was diagnosed as a wart and treated with cryotherapy by another dermatologist several years prior to presentation. Dermatoscopic examination at the current presentation showed a homogenous yellow center with a few peripheral vessels and a faint pink-tan halo (Figure 2). Our differential diagnosis included a recurrent wart, fibrosed pyogenic granuloma, irritated intradermal nevus, skin tag, and adnexal neoplasm. A shave biopsy was performed. Histopathologic analysis revealed multiple aggregations of mildly pleomorphic epithelial cells emanating from the epidermis, with many aggregations containing ductal structures (Figure 3). Rare necrotic and pyknotic cells were present, but no mitotic figures or lymphovascular invasion were identified. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen but negative for Ber-EP4. These findings were consistent with a well-differentiated EPC.

The patient was offered MMS or WLE, with or without sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB). He opted for MMS. The initial 1-cm margin taken during MMS was sufficient to achieve complete tumor extirpation, and the final 3.7×2.5-cm defect was closed primarily. The MMS debulking specimen was sent for permanent sectioning and showed a small focus of residual tumor cells, but no mitoses or lymphovascular invasion were seen. The patient was referred to surgical oncology to discuss the option of SLNB, which he ultimately declined. He also was offered regional or whole-body positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) to rule out metastatic disease, which he also declined. There was no evidence of recurrence or lymphadenopathy 19 months postoperatively.

Comment

Eccrine porocarcinoma is an exceptionally rare adnexal neoplasm that most commonly affects older adults. The average age at diagnosis is 71 years in men and 75 years in women.2 Our case is rare because of the patient’s age. Benign eccrine poromas occur most frequently on the palms, soles, axillae, and forehead where eccrine density is highest; EPC occurs most frequently on the lower extremities.6 It may arise de novo or from malignant transformation of a preexisting benign poroma. Clinically, EPC may present as an asymptomatic pink-brown papule, plaque, or nodule and may have a polypoid or verrucous appearance, as in our patient. Ulceration is common.7 The differential diagnosis often includes nodular basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, pyogenic granuloma, and seborrheic keratosis.

Histologically, EPCs are characterized by aggregations of cohesive basaloid epithelial cells forming eccrine ductal structures.2 Cellular atypia may be extremely subtle but, if present, can be helpful in differentiating malignant from benign lesions. Features of basal and squamous cell carcinoma also may be present. Definitive diagnosis is frequently based on the overall invasive architectural pattern.5 Robson et al2 examined 69 cases of EPC for high-risk histologic features and concluded that tumor depth greater than 7 mm, mitoses greater than 14 per high-power field, and the presence of lymphovascular invasion were independently predictive of mortality. Moreover, after adjusting for mitosis and depth, an infiltrative border vs a pushing border was strongly predictive of local recurrence.2 Immunohistochemical stains, although not necessary for diagnosis, may have utility as adjunctive tools. Cells lining the ducts within EPCs commonly stain positive for carcinoembryonic antigen, though glandular myoepithelial cells stain positive for S-100. Negative Ber-EP4 staining helps to differentiate EPC from basal cell carcinoma. Abnormal expression of p53 and overexpression of p16 also has been described.4

The rarity of EPC has precluded the development of any evidence-based management guidelines. Historically, the standard of care has been WLE with 2- to 3-cm margins. A review of 105 cases of EPC treated with WLE showed 20% local recurrence, 20% regional metastases, and 12% distant metastasis rates.8 Mohs micrographic surgery, which allows examination of 100% of the surgical margin vs less than 1% for WLE with the standard bread-loafing technique, might be expected to achieve higher cure rates. A review of 29 cases treated with MMS monotherapy demonstrated no local recurrences, distant metastasis, or disease-specific deaths with follow-up ranging from 19 months to 6 years.5 One case was associated with regional lymph node metastases that were treated with completion lymphadenectomy and adjuvant radiation therapy.7 The high mortality rate of patients with nodal disease has led some to recommend PET-CT and SLNB for patients with EPC. However, the prognostic value of such procedures has not been clearly defined and there is no demonstrated survival benefit for treatment of widespread disease. Our patient declined both SLNB and PET-CT, and our plan was to follow him clinically with symptom-directed imaging only.

Conclusion

Patients with EPC generally have a favorable prognosis with prompt diagnosis and complete surgical excision. Although most commonly seen in elderly patients, EPC may present in younger patients and may be clinically and histologically nondescript with little cytologic atypia. Based on a small but growing body of literature, MMS appears to be at least as effective as WLE as a primary treatment modality for EPC, while offering the advantage of tissue sparing in cosmetically or functionally important areas.

Eccrine porocarcinoma (EPC), originally described by Pinkus and Mehregan1 in 1963, is an exceedingly rare sweat gland tumor most commonly seen in older patients. Fewer than 300 cases have been reported in the literature, and it is believed to represent only 0.005% to 0.01% of cutaneous malignancies.2 In the absence of established guidelines, wide local excision (WLE) has traditionally been considered the standard of treatment; however, local recurrence and nodal metastasis rates associated with WLE have been reported as high as 20%.3 More recently, a number of case reports and small case series have demonstrated higher cure rates with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), though follow-up is limited.3-5 We describe a case of EPC presenting as a recurrent wart in a 36-year-old man that was successfully treated with MMS.

Case Report

A 36-year-old man with no notable medical history presented with a 0.5×0.5-cm, asymptomatic, flesh-colored, hyperkeratotic, polypoid papule on the right medial thigh (Figure 1). The lesion was diagnosed as a wart and treated with cryotherapy by another dermatologist several years prior to presentation. Dermatoscopic examination at the current presentation showed a homogenous yellow center with a few peripheral vessels and a faint pink-tan halo (Figure 2). Our differential diagnosis included a recurrent wart, fibrosed pyogenic granuloma, irritated intradermal nevus, skin tag, and adnexal neoplasm. A shave biopsy was performed. Histopathologic analysis revealed multiple aggregations of mildly pleomorphic epithelial cells emanating from the epidermis, with many aggregations containing ductal structures (Figure 3). Rare necrotic and pyknotic cells were present, but no mitotic figures or lymphovascular invasion were identified. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen but negative for Ber-EP4. These findings were consistent with a well-differentiated EPC.

The patient was offered MMS or WLE, with or without sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB). He opted for MMS. The initial 1-cm margin taken during MMS was sufficient to achieve complete tumor extirpation, and the final 3.7×2.5-cm defect was closed primarily. The MMS debulking specimen was sent for permanent sectioning and showed a small focus of residual tumor cells, but no mitoses or lymphovascular invasion were seen. The patient was referred to surgical oncology to discuss the option of SLNB, which he ultimately declined. He also was offered regional or whole-body positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) to rule out metastatic disease, which he also declined. There was no evidence of recurrence or lymphadenopathy 19 months postoperatively.

Comment

Eccrine porocarcinoma is an exceptionally rare adnexal neoplasm that most commonly affects older adults. The average age at diagnosis is 71 years in men and 75 years in women.2 Our case is rare because of the patient’s age. Benign eccrine poromas occur most frequently on the palms, soles, axillae, and forehead where eccrine density is highest; EPC occurs most frequently on the lower extremities.6 It may arise de novo or from malignant transformation of a preexisting benign poroma. Clinically, EPC may present as an asymptomatic pink-brown papule, plaque, or nodule and may have a polypoid or verrucous appearance, as in our patient. Ulceration is common.7 The differential diagnosis often includes nodular basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, pyogenic granuloma, and seborrheic keratosis.

Histologically, EPCs are characterized by aggregations of cohesive basaloid epithelial cells forming eccrine ductal structures.2 Cellular atypia may be extremely subtle but, if present, can be helpful in differentiating malignant from benign lesions. Features of basal and squamous cell carcinoma also may be present. Definitive diagnosis is frequently based on the overall invasive architectural pattern.5 Robson et al2 examined 69 cases of EPC for high-risk histologic features and concluded that tumor depth greater than 7 mm, mitoses greater than 14 per high-power field, and the presence of lymphovascular invasion were independently predictive of mortality. Moreover, after adjusting for mitosis and depth, an infiltrative border vs a pushing border was strongly predictive of local recurrence.2 Immunohistochemical stains, although not necessary for diagnosis, may have utility as adjunctive tools. Cells lining the ducts within EPCs commonly stain positive for carcinoembryonic antigen, though glandular myoepithelial cells stain positive for S-100. Negative Ber-EP4 staining helps to differentiate EPC from basal cell carcinoma. Abnormal expression of p53 and overexpression of p16 also has been described.4

The rarity of EPC has precluded the development of any evidence-based management guidelines. Historically, the standard of care has been WLE with 2- to 3-cm margins. A review of 105 cases of EPC treated with WLE showed 20% local recurrence, 20% regional metastases, and 12% distant metastasis rates.8 Mohs micrographic surgery, which allows examination of 100% of the surgical margin vs less than 1% for WLE with the standard bread-loafing technique, might be expected to achieve higher cure rates. A review of 29 cases treated with MMS monotherapy demonstrated no local recurrences, distant metastasis, or disease-specific deaths with follow-up ranging from 19 months to 6 years.5 One case was associated with regional lymph node metastases that were treated with completion lymphadenectomy and adjuvant radiation therapy.7 The high mortality rate of patients with nodal disease has led some to recommend PET-CT and SLNB for patients with EPC. However, the prognostic value of such procedures has not been clearly defined and there is no demonstrated survival benefit for treatment of widespread disease. Our patient declined both SLNB and PET-CT, and our plan was to follow him clinically with symptom-directed imaging only.

Conclusion

Patients with EPC generally have a favorable prognosis with prompt diagnosis and complete surgical excision. Although most commonly seen in elderly patients, EPC may present in younger patients and may be clinically and histologically nondescript with little cytologic atypia. Based on a small but growing body of literature, MMS appears to be at least as effective as WLE as a primary treatment modality for EPC, while offering the advantage of tissue sparing in cosmetically or functionally important areas.

- Pinkus H, Mehregan AH. Epidermatropic eccrine carcinoma. a case combining eccrine poroma and Paget’s dermatoses. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:597-606.

- Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720.

- Tolkachjov SN, Hocker TL, Camilleri MJ, et al. Treatment of porocarcinoma with Mohs micrographic surgery: The Mayo Clinic Experience. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:745-750.

- Tidwell WJ, Mayer JE, Malone J, et al. Treatment of eccrine porocarcinoma with Mohs micrographic surgery: a cases series and literature review. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1078-1083.

- Xu YG, Aylward J, Longley BJ, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma treated by Mohs micrographic surgery: over 6-year follow-up of 12 cases and literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:685-692.

- D’Ambrosia RA, Ward H, Parry E. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the eyelid treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:4:570-571.

- Vleugels FR, Girouard SD, Schmults CD, et al. Metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma after Mohs micrographic surgery: a case report. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:188-191.

- Snow SN, Reizner GT. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the face. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:306-311.

- Pinkus H, Mehregan AH. Epidermatropic eccrine carcinoma. a case combining eccrine poroma and Paget’s dermatoses. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:597-606.

- Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720.

- Tolkachjov SN, Hocker TL, Camilleri MJ, et al. Treatment of porocarcinoma with Mohs micrographic surgery: The Mayo Clinic Experience. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:745-750.

- Tidwell WJ, Mayer JE, Malone J, et al. Treatment of eccrine porocarcinoma with Mohs micrographic surgery: a cases series and literature review. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1078-1083.

- Xu YG, Aylward J, Longley BJ, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma treated by Mohs micrographic surgery: over 6-year follow-up of 12 cases and literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:685-692.

- D’Ambrosia RA, Ward H, Parry E. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the eyelid treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:4:570-571.

- Vleugels FR, Girouard SD, Schmults CD, et al. Metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma after Mohs micrographic surgery: a case report. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:188-191.

- Snow SN, Reizner GT. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the face. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:306-311.

Practice Points

- Eccrine porocarcinoma is more common in older patients (age range, 71–75 years).

- Local recurrence and nodal metastasis are reported as high as 20% with wide local excision.

- Higher cure rates recently have been reported with Mohs micrographic surgery.

Atrophodermalike Guttate Morphea

To the Editor:

Morphea, atrophoderma, guttate lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A), anetoderma, and their subtypes are inflammatory processes ultimately leading to dermal remodeling. We report a case of a scaly, hypopigmented, macular rash that clinically appeared as an entity along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum and demonstrated unique histopathologic changes in both collagen and elastin confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis. This case is a potentially rare variant representing a combination of clinical and microscopic findings.

A 29-year-old woman presented for an increasing number of white spots distributed on the trunk, arms, and legs. She denied local and systemic symptoms. The patient reported that she was stung by 100 wasps 23 years prior. Following the assault, her grandmother placed chewed tobacco leaves atop the painful erythematous wheals and flares. Upon resolution, hypopigmented macules and patches remained in their place. The patient denied associated symptoms or new lesions; she did not seek care at that time.

In her early 20s, the patient noted new, similarly distributed hypopigmented macules and patches without associated arthropod assault. She was treated by an outside dermatologist without result for presumed tinea versicolor. A follow-up superficial shave biopsy cited subtle psoriasiform dermatitis. Topical steroids did not improve the lesions. Her medical history also was remarkable for a reportedly unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear.

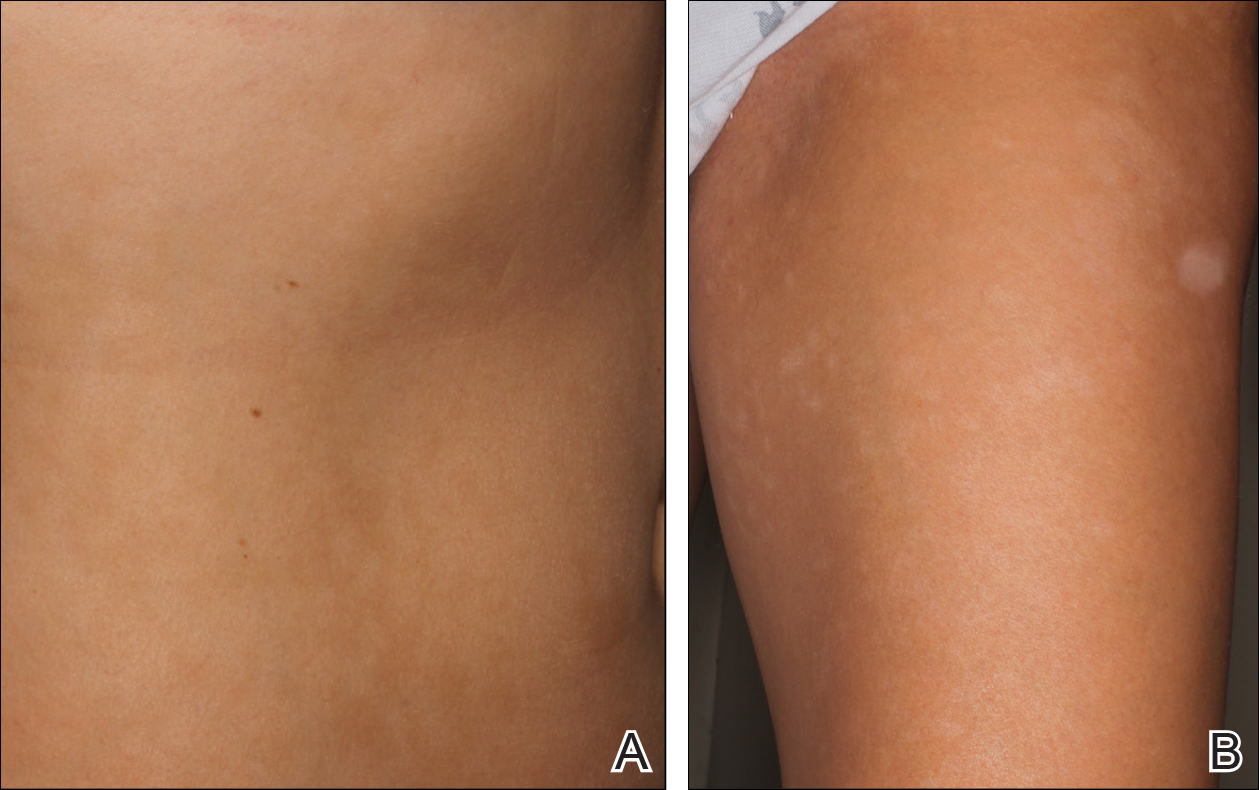

Physical examination revealed 0.5- to 2.0-cm, ill-defined, perifollicular and nonfollicular, slightly scaly macules and patches on the trunk, arms, and legs. There was no follicular plugging (Figure 1A). The hands, feet, face, and mucosal surfaces were spared. She had no family history of similar lesions. Although atrophic in appearance, a single lesion on the left thigh was palpably depressed (Figure 1B). Serology demonstrated a normal complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel, and negative Lyme titers. Light therapy and topical steroids failed to improve the lesions; calcipotriene cream 0.005% made the lesions erythematous and pruritic.

A biopsy from a flank lesion demonstrated a normal epithelium without thinning, a normal basal melanocyte population, and minimally effaced rete ridges. Thin collagen bundles were noted in the upper reticular and papillary dermis with associated fibroplasia (Figure 2). Verhoeff-van Gieson stain revealed decreased and fragmented elastin filaments in the same dermal distribution as the changed collagen (Figure 3). There was no evidence of primary inflammatory disease. The dermis was thinned. Periodic acid–Schiff stain confirmed the absence of hyphae and spores.

The relevant findings in our patient including the following: (1) onset of hypopigmented macules and patches following resolution of a toxic insult; (2) initially stable number of lesions that progressed in number but not size; (3) thinned collagen associated with fibroplasia in the upper reticular and papillary dermis; (4) decreased number and fragmentation of elastin filaments confined to the same region; (5) no congenital lesions or similar lesions in family members; and (6) a complete rotator cuff tear with no findings of a systemic connective-tissue disorder such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

We performed a literature search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using combinations of the terms atrophic, hypopigmented, white, spot disease, confetti-like, guttate, macules, atrophoderma, morphea, anetoderma, elastin, and collagen to identify potentially similar reports of guttate hypopigmented macules demonstrating changes of the collagen and elastin in the papillary and upper reticular dermis. Some variants, namely atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini (APP), guttate morphea, and superficial morphea, demonstrate similar clinical and histopathologic findings.

Findings similar to our case were documented in case reports of 2 women (aged 34 and 42 years)1 presenting with asymptomatic, atrophic, well-demarcated, shiny, hypopigmented macules over the trunk and upper extremities, which demonstrated a thinned epidermis with coarse hyalinized collagen bundles in the mid and lower dermis. There was upper and diffuse dermal elastolysis (patient 1 and patient 2, respectively).1 Our patient’s lesions were hypopigmented and atrophic in appearance but were slightly scaly and also involved the extremities. Distinct from these patient reports, histopathology from our case demonstrated thin packed collagen bundles and decreased fragmented elastin filaments confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis.

Plaque morphea is the most common type of localized scleroderma.2 The subtype APP demonstrates round to ovoid, gray-brown depressions with cliff-drop borders. They may appear flesh colored or hypopigmented.3,4 These sclerodermoid lesions lack the violaceous border classic to morphea. Sclerosis and induration also are typically absent.5 Clinically, our patient’s macules resembled this entity. Histopathologically, APP shows normal epithelium with an increased basal layer pigmentation; preserved adnexal structures; and mid to lower dermal collagen edema, clumping, and homogenization.3,4 Elastic fibers classically are unchanged, with exceptions.6-11 Changes in the collagen and elastin of our patient were unlike those reported in APP, which occur in the mid to lower dermis.

Guttate morphea demonstrates small, pale, minimally indurated, coin-shaped lesions on the trunk. Histopathology reveals less sclerosis and more edema, resembling LS&A.12 The earliest descriptions of this entity describe 3 stages: ivory/chalk white, scaly, and atrophic. Follicular plugging (absent in this patient) and fine scale can exist at any stage.13,14 Flattened rete ridges mark an otherwise preserved epidermis; hyalinized collagen typically is superficial and demonstrates less sclerosis yet increased edema.12-14 Fewer elastic fibers typically are present compared to normal skin. Changes seen in this entity are more superficial, as with our patient, than classic scleroderma. However, classic edema was not found in our patient’s biopsy specimen.

Superficial morphea, occurring predominantly in females, presents with hyperpigmented or hypopigmented patches having minimal to no induration. The lesions typically are asymptomatic. Histopathologically, collagen deposition and inflammation are confined to the superficial dermis without homogenization associated with LS&A, findings that were consistent with this patient’s biopsy.15,16 However, similar to other morpheaform variants, elastic fibers are unchanged.15 Verhoeff-van Gieson stain of the biopsy (Figure 3) showed the decreased and fragmented elastin network in the upper reticular and papillary dermis, making this entity less compatible.

Guttate LS&A may present with interfollicular, bluish white macules or papules coalescing into patches or plaques. Lesions evolve to reveal atrophic thin skin with follicular plugging. Histology demonstrates a thinned epidermis with orthohypokeratosis marked by flattened rete ridges. The dermis reveals short hyalinized collagen fibrils with a loss of elastic fibers in the papillary and upper reticular dermis, giving a homogenized appearance. Early disease is marked by an inflammatory infiltrate.17 Most of these findings are consistent with our patient’s pathology, which was confined to the upper dermis. Lacking, however, were characteristic findings of LS&A, including upper dermal homogenization, near-total effacement of rete ridges, orthokeratosis, and vacuolar degeneration at the dermoepidermal junction. As such, this entity is less compatible.

Atrophoderma elastolyticum discretum has clinical features of atrophoderma with elastolytic histopathologic findings.1 Anetoderma presents with outpouchings of atrophic skin with a surrounding ring of normal tissue. Histopathologically, this entity shows normal collagen with elastolysis; there also is a decrease in desmosine, an elastin cross-linker.1,3 Neither the clinical nor histopathologic findings in this patient matched these 2 entities.

The reported chronologic association of these lesions with an arthropod assault raised suspicion to their association with toxic insult or postinflammatory changes. One study reported mechanical trauma, including insect bites, as a possible inciting factor of morphea.11 These data, gathered from patient surveys, reported trauma associated to lesion development.1,17 A review of the literature regarding atrophoderma, morphea, and LS&A failed to identify pathogenic changes seen in this patient following initial trauma. Moreover, although it is difficult to prove causality in the formation of the original hypopigmented spots, the development of identical spots in a similar distribution without further trauma suggests against these etiologies to fully explain her lesions. Nonetheless, circumstance makes it difficult to prove whether the original arthropod insult spurred a smoldering reactive process that caused the newer lesions.

Hereditary connective-tissue disorders also were considered in the differential diagnosis. Because of the patient’s history of an unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome was considered; however, the remainder of her examination was normal, making a syndromic systemic disorder a less likely etiology.Because of the distinct clinical and histopathologic findings, this case may represent a rare and previously unreported variant of morphea. Clinically, these hypopigmented macules and patches exist somewhere along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum. Histopathologic findings do not conform to prior reports. The name atrophodermalike guttate morphea may be an appropriate appellation. It is possible this presentation represents a variant of what dermatologists have referred to as white spot disease.18 We hope that this case may bring others to discussion, allowing for the identification of a more precise entity and etiology so that patients may receive more directed therapy.

- Aksoy B, Ustün H, Gulbahce R, et al. Confetti-like macular atrophy: a new entity? J Dermatol. 2009;36:592-597.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Bauer EA, et al. Morphea and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. clinical and histopathologic studies in patients with combined features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:271-279.

- Buechner SA, Rufli T. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. clinical and histopathologic findings and antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi in thirty-four patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:441-446.

- Saleh Z, Abbas O, Dahdah MJ, et al. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini: a clinical and histopathological study. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1108-1114.

- Canizares O, Sachs PM, Jaimovich L, et al. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Arch Dermatol. 1958;77:42-58; discussion 58-60.

- Pullara TJ, Lober CW, Fenske NA. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:643-645.

- Jablonska S, Szczepanski A. Atrophoderma Pasini-Pierini: is it an entity? Dermatologica. 1962;125:226-242.

- Ang G, Hyde PM, Lee JB. Unilateral congenital linear atrophoderma of the leg. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:350-354.

- Miteva L, Kadurina M. Unilateral idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1391-1393.

- Kee CE, Brothers WS, New W. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini with coexistent morphea. a case report. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:100-103.

- Zulian F, Athreya BH, Laxer R, et al. Juvenile localized scleroderma: clinical and epidemiological features in 750 children. an international study. Rheumatology. 2006;45:614-620.

- Winkelmann RK. Localized cutaneous scleroderma. Semin Dermatol. 1985;4:90-103.

- Dore SE. Two cases of morphoea guttata. Proc R Soc Med. 1918;11:26-28.

- Dore SE. Guttate morphoea. Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:3-5.

- McNiff JM, Glusac EJ, Lazova RZ, et al. Morphea limited to the superficial reticular dermis: an underrecognized histologic phenomenon. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:315-319.

- Jacobson L, Palazij R, Jaworsky C. Superficial morphea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:323-325.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. London, England: Mosby Elsevier; 2007.

- Bunch JL. White-spot disease (morphoea guttata). Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:24-27.

To the Editor:

Morphea, atrophoderma, guttate lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A), anetoderma, and their subtypes are inflammatory processes ultimately leading to dermal remodeling. We report a case of a scaly, hypopigmented, macular rash that clinically appeared as an entity along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum and demonstrated unique histopathologic changes in both collagen and elastin confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis. This case is a potentially rare variant representing a combination of clinical and microscopic findings.

A 29-year-old woman presented for an increasing number of white spots distributed on the trunk, arms, and legs. She denied local and systemic symptoms. The patient reported that she was stung by 100 wasps 23 years prior. Following the assault, her grandmother placed chewed tobacco leaves atop the painful erythematous wheals and flares. Upon resolution, hypopigmented macules and patches remained in their place. The patient denied associated symptoms or new lesions; she did not seek care at that time.

In her early 20s, the patient noted new, similarly distributed hypopigmented macules and patches without associated arthropod assault. She was treated by an outside dermatologist without result for presumed tinea versicolor. A follow-up superficial shave biopsy cited subtle psoriasiform dermatitis. Topical steroids did not improve the lesions. Her medical history also was remarkable for a reportedly unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear.

Physical examination revealed 0.5- to 2.0-cm, ill-defined, perifollicular and nonfollicular, slightly scaly macules and patches on the trunk, arms, and legs. There was no follicular plugging (Figure 1A). The hands, feet, face, and mucosal surfaces were spared. She had no family history of similar lesions. Although atrophic in appearance, a single lesion on the left thigh was palpably depressed (Figure 1B). Serology demonstrated a normal complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel, and negative Lyme titers. Light therapy and topical steroids failed to improve the lesions; calcipotriene cream 0.005% made the lesions erythematous and pruritic.

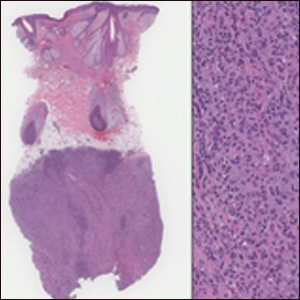

A biopsy from a flank lesion demonstrated a normal epithelium without thinning, a normal basal melanocyte population, and minimally effaced rete ridges. Thin collagen bundles were noted in the upper reticular and papillary dermis with associated fibroplasia (Figure 2). Verhoeff-van Gieson stain revealed decreased and fragmented elastin filaments in the same dermal distribution as the changed collagen (Figure 3). There was no evidence of primary inflammatory disease. The dermis was thinned. Periodic acid–Schiff stain confirmed the absence of hyphae and spores.

The relevant findings in our patient including the following: (1) onset of hypopigmented macules and patches following resolution of a toxic insult; (2) initially stable number of lesions that progressed in number but not size; (3) thinned collagen associated with fibroplasia in the upper reticular and papillary dermis; (4) decreased number and fragmentation of elastin filaments confined to the same region; (5) no congenital lesions or similar lesions in family members; and (6) a complete rotator cuff tear with no findings of a systemic connective-tissue disorder such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

We performed a literature search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using combinations of the terms atrophic, hypopigmented, white, spot disease, confetti-like, guttate, macules, atrophoderma, morphea, anetoderma, elastin, and collagen to identify potentially similar reports of guttate hypopigmented macules demonstrating changes of the collagen and elastin in the papillary and upper reticular dermis. Some variants, namely atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini (APP), guttate morphea, and superficial morphea, demonstrate similar clinical and histopathologic findings.

Findings similar to our case were documented in case reports of 2 women (aged 34 and 42 years)1 presenting with asymptomatic, atrophic, well-demarcated, shiny, hypopigmented macules over the trunk and upper extremities, which demonstrated a thinned epidermis with coarse hyalinized collagen bundles in the mid and lower dermis. There was upper and diffuse dermal elastolysis (patient 1 and patient 2, respectively).1 Our patient’s lesions were hypopigmented and atrophic in appearance but were slightly scaly and also involved the extremities. Distinct from these patient reports, histopathology from our case demonstrated thin packed collagen bundles and decreased fragmented elastin filaments confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis.

Plaque morphea is the most common type of localized scleroderma.2 The subtype APP demonstrates round to ovoid, gray-brown depressions with cliff-drop borders. They may appear flesh colored or hypopigmented.3,4 These sclerodermoid lesions lack the violaceous border classic to morphea. Sclerosis and induration also are typically absent.5 Clinically, our patient’s macules resembled this entity. Histopathologically, APP shows normal epithelium with an increased basal layer pigmentation; preserved adnexal structures; and mid to lower dermal collagen edema, clumping, and homogenization.3,4 Elastic fibers classically are unchanged, with exceptions.6-11 Changes in the collagen and elastin of our patient were unlike those reported in APP, which occur in the mid to lower dermis.

Guttate morphea demonstrates small, pale, minimally indurated, coin-shaped lesions on the trunk. Histopathology reveals less sclerosis and more edema, resembling LS&A.12 The earliest descriptions of this entity describe 3 stages: ivory/chalk white, scaly, and atrophic. Follicular plugging (absent in this patient) and fine scale can exist at any stage.13,14 Flattened rete ridges mark an otherwise preserved epidermis; hyalinized collagen typically is superficial and demonstrates less sclerosis yet increased edema.12-14 Fewer elastic fibers typically are present compared to normal skin. Changes seen in this entity are more superficial, as with our patient, than classic scleroderma. However, classic edema was not found in our patient’s biopsy specimen.

Superficial morphea, occurring predominantly in females, presents with hyperpigmented or hypopigmented patches having minimal to no induration. The lesions typically are asymptomatic. Histopathologically, collagen deposition and inflammation are confined to the superficial dermis without homogenization associated with LS&A, findings that were consistent with this patient’s biopsy.15,16 However, similar to other morpheaform variants, elastic fibers are unchanged.15 Verhoeff-van Gieson stain of the biopsy (Figure 3) showed the decreased and fragmented elastin network in the upper reticular and papillary dermis, making this entity less compatible.

Guttate LS&A may present with interfollicular, bluish white macules or papules coalescing into patches or plaques. Lesions evolve to reveal atrophic thin skin with follicular plugging. Histology demonstrates a thinned epidermis with orthohypokeratosis marked by flattened rete ridges. The dermis reveals short hyalinized collagen fibrils with a loss of elastic fibers in the papillary and upper reticular dermis, giving a homogenized appearance. Early disease is marked by an inflammatory infiltrate.17 Most of these findings are consistent with our patient’s pathology, which was confined to the upper dermis. Lacking, however, were characteristic findings of LS&A, including upper dermal homogenization, near-total effacement of rete ridges, orthokeratosis, and vacuolar degeneration at the dermoepidermal junction. As such, this entity is less compatible.

Atrophoderma elastolyticum discretum has clinical features of atrophoderma with elastolytic histopathologic findings.1 Anetoderma presents with outpouchings of atrophic skin with a surrounding ring of normal tissue. Histopathologically, this entity shows normal collagen with elastolysis; there also is a decrease in desmosine, an elastin cross-linker.1,3 Neither the clinical nor histopathologic findings in this patient matched these 2 entities.

The reported chronologic association of these lesions with an arthropod assault raised suspicion to their association with toxic insult or postinflammatory changes. One study reported mechanical trauma, including insect bites, as a possible inciting factor of morphea.11 These data, gathered from patient surveys, reported trauma associated to lesion development.1,17 A review of the literature regarding atrophoderma, morphea, and LS&A failed to identify pathogenic changes seen in this patient following initial trauma. Moreover, although it is difficult to prove causality in the formation of the original hypopigmented spots, the development of identical spots in a similar distribution without further trauma suggests against these etiologies to fully explain her lesions. Nonetheless, circumstance makes it difficult to prove whether the original arthropod insult spurred a smoldering reactive process that caused the newer lesions.

Hereditary connective-tissue disorders also were considered in the differential diagnosis. Because of the patient’s history of an unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome was considered; however, the remainder of her examination was normal, making a syndromic systemic disorder a less likely etiology.Because of the distinct clinical and histopathologic findings, this case may represent a rare and previously unreported variant of morphea. Clinically, these hypopigmented macules and patches exist somewhere along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum. Histopathologic findings do not conform to prior reports. The name atrophodermalike guttate morphea may be an appropriate appellation. It is possible this presentation represents a variant of what dermatologists have referred to as white spot disease.18 We hope that this case may bring others to discussion, allowing for the identification of a more precise entity and etiology so that patients may receive more directed therapy.

To the Editor:

Morphea, atrophoderma, guttate lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A), anetoderma, and their subtypes are inflammatory processes ultimately leading to dermal remodeling. We report a case of a scaly, hypopigmented, macular rash that clinically appeared as an entity along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum and demonstrated unique histopathologic changes in both collagen and elastin confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis. This case is a potentially rare variant representing a combination of clinical and microscopic findings.

A 29-year-old woman presented for an increasing number of white spots distributed on the trunk, arms, and legs. She denied local and systemic symptoms. The patient reported that she was stung by 100 wasps 23 years prior. Following the assault, her grandmother placed chewed tobacco leaves atop the painful erythematous wheals and flares. Upon resolution, hypopigmented macules and patches remained in their place. The patient denied associated symptoms or new lesions; she did not seek care at that time.

In her early 20s, the patient noted new, similarly distributed hypopigmented macules and patches without associated arthropod assault. She was treated by an outside dermatologist without result for presumed tinea versicolor. A follow-up superficial shave biopsy cited subtle psoriasiform dermatitis. Topical steroids did not improve the lesions. Her medical history also was remarkable for a reportedly unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear.

Physical examination revealed 0.5- to 2.0-cm, ill-defined, perifollicular and nonfollicular, slightly scaly macules and patches on the trunk, arms, and legs. There was no follicular plugging (Figure 1A). The hands, feet, face, and mucosal surfaces were spared. She had no family history of similar lesions. Although atrophic in appearance, a single lesion on the left thigh was palpably depressed (Figure 1B). Serology demonstrated a normal complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel, and negative Lyme titers. Light therapy and topical steroids failed to improve the lesions; calcipotriene cream 0.005% made the lesions erythematous and pruritic.

A biopsy from a flank lesion demonstrated a normal epithelium without thinning, a normal basal melanocyte population, and minimally effaced rete ridges. Thin collagen bundles were noted in the upper reticular and papillary dermis with associated fibroplasia (Figure 2). Verhoeff-van Gieson stain revealed decreased and fragmented elastin filaments in the same dermal distribution as the changed collagen (Figure 3). There was no evidence of primary inflammatory disease. The dermis was thinned. Periodic acid–Schiff stain confirmed the absence of hyphae and spores.

The relevant findings in our patient including the following: (1) onset of hypopigmented macules and patches following resolution of a toxic insult; (2) initially stable number of lesions that progressed in number but not size; (3) thinned collagen associated with fibroplasia in the upper reticular and papillary dermis; (4) decreased number and fragmentation of elastin filaments confined to the same region; (5) no congenital lesions or similar lesions in family members; and (6) a complete rotator cuff tear with no findings of a systemic connective-tissue disorder such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

We performed a literature search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using combinations of the terms atrophic, hypopigmented, white, spot disease, confetti-like, guttate, macules, atrophoderma, morphea, anetoderma, elastin, and collagen to identify potentially similar reports of guttate hypopigmented macules demonstrating changes of the collagen and elastin in the papillary and upper reticular dermis. Some variants, namely atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini (APP), guttate morphea, and superficial morphea, demonstrate similar clinical and histopathologic findings.

Findings similar to our case were documented in case reports of 2 women (aged 34 and 42 years)1 presenting with asymptomatic, atrophic, well-demarcated, shiny, hypopigmented macules over the trunk and upper extremities, which demonstrated a thinned epidermis with coarse hyalinized collagen bundles in the mid and lower dermis. There was upper and diffuse dermal elastolysis (patient 1 and patient 2, respectively).1 Our patient’s lesions were hypopigmented and atrophic in appearance but were slightly scaly and also involved the extremities. Distinct from these patient reports, histopathology from our case demonstrated thin packed collagen bundles and decreased fragmented elastin filaments confined to the upper reticular and papillary dermis.

Plaque morphea is the most common type of localized scleroderma.2 The subtype APP demonstrates round to ovoid, gray-brown depressions with cliff-drop borders. They may appear flesh colored or hypopigmented.3,4 These sclerodermoid lesions lack the violaceous border classic to morphea. Sclerosis and induration also are typically absent.5 Clinically, our patient’s macules resembled this entity. Histopathologically, APP shows normal epithelium with an increased basal layer pigmentation; preserved adnexal structures; and mid to lower dermal collagen edema, clumping, and homogenization.3,4 Elastic fibers classically are unchanged, with exceptions.6-11 Changes in the collagen and elastin of our patient were unlike those reported in APP, which occur in the mid to lower dermis.

Guttate morphea demonstrates small, pale, minimally indurated, coin-shaped lesions on the trunk. Histopathology reveals less sclerosis and more edema, resembling LS&A.12 The earliest descriptions of this entity describe 3 stages: ivory/chalk white, scaly, and atrophic. Follicular plugging (absent in this patient) and fine scale can exist at any stage.13,14 Flattened rete ridges mark an otherwise preserved epidermis; hyalinized collagen typically is superficial and demonstrates less sclerosis yet increased edema.12-14 Fewer elastic fibers typically are present compared to normal skin. Changes seen in this entity are more superficial, as with our patient, than classic scleroderma. However, classic edema was not found in our patient’s biopsy specimen.

Superficial morphea, occurring predominantly in females, presents with hyperpigmented or hypopigmented patches having minimal to no induration. The lesions typically are asymptomatic. Histopathologically, collagen deposition and inflammation are confined to the superficial dermis without homogenization associated with LS&A, findings that were consistent with this patient’s biopsy.15,16 However, similar to other morpheaform variants, elastic fibers are unchanged.15 Verhoeff-van Gieson stain of the biopsy (Figure 3) showed the decreased and fragmented elastin network in the upper reticular and papillary dermis, making this entity less compatible.

Guttate LS&A may present with interfollicular, bluish white macules or papules coalescing into patches or plaques. Lesions evolve to reveal atrophic thin skin with follicular plugging. Histology demonstrates a thinned epidermis with orthohypokeratosis marked by flattened rete ridges. The dermis reveals short hyalinized collagen fibrils with a loss of elastic fibers in the papillary and upper reticular dermis, giving a homogenized appearance. Early disease is marked by an inflammatory infiltrate.17 Most of these findings are consistent with our patient’s pathology, which was confined to the upper dermis. Lacking, however, were characteristic findings of LS&A, including upper dermal homogenization, near-total effacement of rete ridges, orthokeratosis, and vacuolar degeneration at the dermoepidermal junction. As such, this entity is less compatible.

Atrophoderma elastolyticum discretum has clinical features of atrophoderma with elastolytic histopathologic findings.1 Anetoderma presents with outpouchings of atrophic skin with a surrounding ring of normal tissue. Histopathologically, this entity shows normal collagen with elastolysis; there also is a decrease in desmosine, an elastin cross-linker.1,3 Neither the clinical nor histopathologic findings in this patient matched these 2 entities.

The reported chronologic association of these lesions with an arthropod assault raised suspicion to their association with toxic insult or postinflammatory changes. One study reported mechanical trauma, including insect bites, as a possible inciting factor of morphea.11 These data, gathered from patient surveys, reported trauma associated to lesion development.1,17 A review of the literature regarding atrophoderma, morphea, and LS&A failed to identify pathogenic changes seen in this patient following initial trauma. Moreover, although it is difficult to prove causality in the formation of the original hypopigmented spots, the development of identical spots in a similar distribution without further trauma suggests against these etiologies to fully explain her lesions. Nonetheless, circumstance makes it difficult to prove whether the original arthropod insult spurred a smoldering reactive process that caused the newer lesions.

Hereditary connective-tissue disorders also were considered in the differential diagnosis. Because of the patient’s history of an unprovoked complete rotator cuff tear, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome was considered; however, the remainder of her examination was normal, making a syndromic systemic disorder a less likely etiology.Because of the distinct clinical and histopathologic findings, this case may represent a rare and previously unreported variant of morphea. Clinically, these hypopigmented macules and patches exist somewhere along the morphea-atrophoderma spectrum. Histopathologic findings do not conform to prior reports. The name atrophodermalike guttate morphea may be an appropriate appellation. It is possible this presentation represents a variant of what dermatologists have referred to as white spot disease.18 We hope that this case may bring others to discussion, allowing for the identification of a more precise entity and etiology so that patients may receive more directed therapy.

- Aksoy B, Ustün H, Gulbahce R, et al. Confetti-like macular atrophy: a new entity? J Dermatol. 2009;36:592-597.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Bauer EA, et al. Morphea and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. clinical and histopathologic studies in patients with combined features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:271-279.

- Buechner SA, Rufli T. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. clinical and histopathologic findings and antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi in thirty-four patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:441-446.

- Saleh Z, Abbas O, Dahdah MJ, et al. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini: a clinical and histopathological study. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1108-1114.

- Canizares O, Sachs PM, Jaimovich L, et al. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Arch Dermatol. 1958;77:42-58; discussion 58-60.

- Pullara TJ, Lober CW, Fenske NA. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:643-645.

- Jablonska S, Szczepanski A. Atrophoderma Pasini-Pierini: is it an entity? Dermatologica. 1962;125:226-242.

- Ang G, Hyde PM, Lee JB. Unilateral congenital linear atrophoderma of the leg. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:350-354.

- Miteva L, Kadurina M. Unilateral idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1391-1393.

- Kee CE, Brothers WS, New W. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini with coexistent morphea. a case report. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:100-103.

- Zulian F, Athreya BH, Laxer R, et al. Juvenile localized scleroderma: clinical and epidemiological features in 750 children. an international study. Rheumatology. 2006;45:614-620.

- Winkelmann RK. Localized cutaneous scleroderma. Semin Dermatol. 1985;4:90-103.

- Dore SE. Two cases of morphoea guttata. Proc R Soc Med. 1918;11:26-28.

- Dore SE. Guttate morphoea. Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:3-5.

- McNiff JM, Glusac EJ, Lazova RZ, et al. Morphea limited to the superficial reticular dermis: an underrecognized histologic phenomenon. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:315-319.

- Jacobson L, Palazij R, Jaworsky C. Superficial morphea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:323-325.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. London, England: Mosby Elsevier; 2007.

- Bunch JL. White-spot disease (morphoea guttata). Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:24-27.

- Aksoy B, Ustün H, Gulbahce R, et al. Confetti-like macular atrophy: a new entity? J Dermatol. 2009;36:592-597.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Bauer EA, et al. Morphea and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. clinical and histopathologic studies in patients with combined features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:271-279.

- Buechner SA, Rufli T. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. clinical and histopathologic findings and antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi in thirty-four patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:441-446.

- Saleh Z, Abbas O, Dahdah MJ, et al. Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini: a clinical and histopathological study. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:1108-1114.

- Canizares O, Sachs PM, Jaimovich L, et al. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Arch Dermatol. 1958;77:42-58; discussion 58-60.

- Pullara TJ, Lober CW, Fenske NA. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:643-645.

- Jablonska S, Szczepanski A. Atrophoderma Pasini-Pierini: is it an entity? Dermatologica. 1962;125:226-242.

- Ang G, Hyde PM, Lee JB. Unilateral congenital linear atrophoderma of the leg. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:350-354.

- Miteva L, Kadurina M. Unilateral idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1391-1393.

- Kee CE, Brothers WS, New W. Idiopathic atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini with coexistent morphea. a case report. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:100-103.

- Zulian F, Athreya BH, Laxer R, et al. Juvenile localized scleroderma: clinical and epidemiological features in 750 children. an international study. Rheumatology. 2006;45:614-620.

- Winkelmann RK. Localized cutaneous scleroderma. Semin Dermatol. 1985;4:90-103.

- Dore SE. Two cases of morphoea guttata. Proc R Soc Med. 1918;11:26-28.

- Dore SE. Guttate morphoea. Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:3-5.

- McNiff JM, Glusac EJ, Lazova RZ, et al. Morphea limited to the superficial reticular dermis: an underrecognized histologic phenomenon. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:315-319.

- Jacobson L, Palazij R, Jaworsky C. Superficial morphea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:323-325.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. London, England: Mosby Elsevier; 2007.

- Bunch JL. White-spot disease (morphoea guttata). Proc R Soc Med. 1919;12:24-27.

Practice Points

- Atrophodermalike guttate morphea is a potentially underreported or undescribed entity consisting of a combination of clinicopathologic features.

- Widespread hypopigmented macules on the trunk and extremities marked by thinned collagen, fibroplasia, and altered fragmented elastin in the papillary dermis and upper reticular dermis are the key features.

- Atrophoderma, morphea, and lichen sclerosus et atrophicus should be ruled out during clinical workup.

Asymptomatic Subcutaneous Nodule on the Cheek

The Diagnosis: Lymphoepitheliomalike Carcinoma of the Skin

The term lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin (LELCS) initially was proposed by Swanson et al1 in 1988 when they described 5 patients with cutaneous neoplasms histologically resembling nasopharyngeal carcinoma, also known as lymphoepithelioma. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin revealed over 60 cases of LELCS since 1988. However, unlike nasopharyngeal carcinoma, LELCS has not been associated with Epstein-Barr virus, with the exception of 1 known reported case.2 The clinical appearance of LELCS is nonspecific but usually presents as a flesh-colored to erythematous nodule, as was seen in the current case. Lesions commonly are found on the head and neck in middle-aged to elderly patients with a slight male predominance.2

On histology, LELCS is characterized by aggregations of large, atypical epithelioid cells surrounded by a dense lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate (right quiz image). The neoplasm tends to reside within the deep dermis and/or subcutis1 without appreciable epidermal involvement (left quiz image). The atypical epithelioid cells demonstrate positive immunoreactivity for cytokeratins (right quiz image inset), p40/p63, and epithelial membrane antigen,3 and the surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate stains positively for leukocyte common antigen. The tumor histogenesis still is unknown, although an epidermal origin has been suggested given its staining pattern.2 Other investigators have postulated on an adnexal origin, citing the tumor's dermal location along with case reports describing possible glandular, sebaceous, or follicular differentiation.2,4

Treatment for LELCS can include either standard surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery, with radiation reserved for lymph node involvement, tumor recurrence, or poor surgical candidates.2,3,5 With appropriate therapy, prognosis may be considered favorable. Data from 49 LELCS patients presenting from 1988 and 2008 showed that 36 (73.5%) had no evidence of recurrence after treatment with standard surgical excision, 4 (8.2%) had local recurrence, and 6 (12.2%) developed lymph node metastasis, which led to death in 1 (2.0%) patient.2

Given the histologic similarity of LELCS to nasopharyngeal carcinoma, it is important to rule out the possibility of cutaneous metastasis, which can be done by testing for Epstein-Barr virus and performing either computed tomography imaging or comprehensive laryngoscopic examination of the head and neck region. In the current case, the patient was referred for laryngoscopy, at which time no suspicious lesions were identified. He subsequently underwent treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery, and the tumor was cleared after 2 surgical stages. At 5-month follow-up, the patient continued to do well with no signs of clinical recurrence.

Cutaneous lymphadenoma may be included in the differential diagnosis for LELCS on histopathology. This neoplasm is characterized by a well-circumscribed dermal proliferation of basaloid tumor islands within a fibrotic stroma (Figure 1). The basaloid cells may display peripheral palisading, and lymphocytes often are seen infiltrating the tumor lobules and the surrounding stroma (Figure 1 inset). Clinically, cutaneous lymphadenomas are slowly growing nodules that typically occur in young to middle-aged patients,4,6 unlike LELCS, which is more commonly observed in middle-aged to elderly patients.2

The dense lymphocytic infiltrate seen in LELCS may obscure the neoplastic epithelioid cells and in doing so may mimic a lymphoproliferative disorder, such as lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP). Lymphomatoid papulosis is a chronic CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder consisting of recurrent crops of self-resolving papulonodules occurring on the trunk, arms, and legs. The average age of onset is in the third to fourth decades of life. Histology is dependent on the subtype; type A, the most common subtype, displays a wedge-shaped dermal infiltrate consisting of small lymphocytes (Figure 2) admixed with larger CD30+ atypical lymphocytes with prominent nucleoli (Figure 2 inset).7 Bizarre, binucleated forms resembling Reed-Sternberg cells also may be observed along with hallmark cells, which contain a horseshoe-shaped nucleus. The presence of admixed neutrophils and eosinophils also are common in type A LyP, a feature that is not characteristic of LELCS. Moreover, the atypical cells in LyP would not stain positively for epithelial markers as they would in LELCS.

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare condition that usually presents with painless cervical lymphadenopathy, typically in the first and second decades of life. Skin involvement can be seen in a small subset of extranodal cases, but cutaneous involvement alone is uncommon. On histopathology, cutaneous lesions are characterized by a dense dermal infiltrate of atypical histiocytes with vesicular nuclei and pale cytoplasm admixed with inflammatory cells, including lymphocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells (Figure 3). Intracytoplasmic inflammatory cells or emperipolesis often is appreciated (Figure 3 inset).8,9 The atypical histiocytes stain positively for S100 and negatively for CD1a.

Lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin sometimes is considered to be a poorly differentiated, inflamed variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).10 A number of features may allow distinction of a primary cutaneous SCC from LELCS; for instance, SCC is more likely to have an epidermal connection and at least focal signs of squamous differentiation,11 which can include the presence of poorly differentiated epithelial cells with mitoses (Figure 4), keratin pearls, dyskeratotic cells, or intercellular bridges.12 Moreover, SCCs have a more variable surrounding inflammatory infiltrate compared to LELCS.

- Swanson SA, Cooper PH, Mills SE, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin. Mod Pathol. 1988;1:359-365.

- Aoki R, Mitsui H, Harada K, et al. A case of lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:681-684.

- Morteza Abedi S, Salama S, Alowami S. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: case report and approach to surgical pathology sign out. Rare Tumors. 2013;5:E47.

- Requena L, Sánchez Yus E, Jiménez E, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: a light-microscopic and immunohistochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:541-548.

- Welch PQ, Williams SB, Foss RD, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of head and neck skin: a systematic analysis of 11 cases and review of literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:78-86.

- Santa Cruz DJ, Barr RJ, Headington JT. Cutaneous lymphadenoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:101-110.

- Patterson JW. Cutaneous infiltrates--lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Patterson JW, Hosler GA, eds. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 2016:1186-1189.

- Patterson JW. Cutaneous infiltrates--nonlymphoid. In: Patterson JW, Hosler GA, eds. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 2016:1158.

- Skiljo M, Garcia-Lora E, Tercedor J, et al. Purely cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Dermatology. 1995;191:49-51.

- Wang G, Bordeaux JS, Rowe DJ, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma vs inflamed squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1367-1368.

- Hall G, Duncan A, Azurdia R, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: a case with lymph node metastases at presentation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:211-215.

- Lind AC, Breer WA, Wick MR. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin with apparent origin in the epidermis--a pattern or an entity? a case report. Cancer. 1999;85:884-890.

The Diagnosis: Lymphoepitheliomalike Carcinoma of the Skin

The term lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin (LELCS) initially was proposed by Swanson et al1 in 1988 when they described 5 patients with cutaneous neoplasms histologically resembling nasopharyngeal carcinoma, also known as lymphoepithelioma. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin revealed over 60 cases of LELCS since 1988. However, unlike nasopharyngeal carcinoma, LELCS has not been associated with Epstein-Barr virus, with the exception of 1 known reported case.2 The clinical appearance of LELCS is nonspecific but usually presents as a flesh-colored to erythematous nodule, as was seen in the current case. Lesions commonly are found on the head and neck in middle-aged to elderly patients with a slight male predominance.2

On histology, LELCS is characterized by aggregations of large, atypical epithelioid cells surrounded by a dense lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate (right quiz image). The neoplasm tends to reside within the deep dermis and/or subcutis1 without appreciable epidermal involvement (left quiz image). The atypical epithelioid cells demonstrate positive immunoreactivity for cytokeratins (right quiz image inset), p40/p63, and epithelial membrane antigen,3 and the surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate stains positively for leukocyte common antigen. The tumor histogenesis still is unknown, although an epidermal origin has been suggested given its staining pattern.2 Other investigators have postulated on an adnexal origin, citing the tumor's dermal location along with case reports describing possible glandular, sebaceous, or follicular differentiation.2,4

Treatment for LELCS can include either standard surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery, with radiation reserved for lymph node involvement, tumor recurrence, or poor surgical candidates.2,3,5 With appropriate therapy, prognosis may be considered favorable. Data from 49 LELCS patients presenting from 1988 and 2008 showed that 36 (73.5%) had no evidence of recurrence after treatment with standard surgical excision, 4 (8.2%) had local recurrence, and 6 (12.2%) developed lymph node metastasis, which led to death in 1 (2.0%) patient.2

Given the histologic similarity of LELCS to nasopharyngeal carcinoma, it is important to rule out the possibility of cutaneous metastasis, which can be done by testing for Epstein-Barr virus and performing either computed tomography imaging or comprehensive laryngoscopic examination of the head and neck region. In the current case, the patient was referred for laryngoscopy, at which time no suspicious lesions were identified. He subsequently underwent treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery, and the tumor was cleared after 2 surgical stages. At 5-month follow-up, the patient continued to do well with no signs of clinical recurrence.

Cutaneous lymphadenoma may be included in the differential diagnosis for LELCS on histopathology. This neoplasm is characterized by a well-circumscribed dermal proliferation of basaloid tumor islands within a fibrotic stroma (Figure 1). The basaloid cells may display peripheral palisading, and lymphocytes often are seen infiltrating the tumor lobules and the surrounding stroma (Figure 1 inset). Clinically, cutaneous lymphadenomas are slowly growing nodules that typically occur in young to middle-aged patients,4,6 unlike LELCS, which is more commonly observed in middle-aged to elderly patients.2

The dense lymphocytic infiltrate seen in LELCS may obscure the neoplastic epithelioid cells and in doing so may mimic a lymphoproliferative disorder, such as lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP). Lymphomatoid papulosis is a chronic CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder consisting of recurrent crops of self-resolving papulonodules occurring on the trunk, arms, and legs. The average age of onset is in the third to fourth decades of life. Histology is dependent on the subtype; type A, the most common subtype, displays a wedge-shaped dermal infiltrate consisting of small lymphocytes (Figure 2) admixed with larger CD30+ atypical lymphocytes with prominent nucleoli (Figure 2 inset).7 Bizarre, binucleated forms resembling Reed-Sternberg cells also may be observed along with hallmark cells, which contain a horseshoe-shaped nucleus. The presence of admixed neutrophils and eosinophils also are common in type A LyP, a feature that is not characteristic of LELCS. Moreover, the atypical cells in LyP would not stain positively for epithelial markers as they would in LELCS.

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare condition that usually presents with painless cervical lymphadenopathy, typically in the first and second decades of life. Skin involvement can be seen in a small subset of extranodal cases, but cutaneous involvement alone is uncommon. On histopathology, cutaneous lesions are characterized by a dense dermal infiltrate of atypical histiocytes with vesicular nuclei and pale cytoplasm admixed with inflammatory cells, including lymphocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells (Figure 3). Intracytoplasmic inflammatory cells or emperipolesis often is appreciated (Figure 3 inset).8,9 The atypical histiocytes stain positively for S100 and negatively for CD1a.

Lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin sometimes is considered to be a poorly differentiated, inflamed variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).10 A number of features may allow distinction of a primary cutaneous SCC from LELCS; for instance, SCC is more likely to have an epidermal connection and at least focal signs of squamous differentiation,11 which can include the presence of poorly differentiated epithelial cells with mitoses (Figure 4), keratin pearls, dyskeratotic cells, or intercellular bridges.12 Moreover, SCCs have a more variable surrounding inflammatory infiltrate compared to LELCS.

The Diagnosis: Lymphoepitheliomalike Carcinoma of the Skin

The term lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin (LELCS) initially was proposed by Swanson et al1 in 1988 when they described 5 patients with cutaneous neoplasms histologically resembling nasopharyngeal carcinoma, also known as lymphoepithelioma. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin revealed over 60 cases of LELCS since 1988. However, unlike nasopharyngeal carcinoma, LELCS has not been associated with Epstein-Barr virus, with the exception of 1 known reported case.2 The clinical appearance of LELCS is nonspecific but usually presents as a flesh-colored to erythematous nodule, as was seen in the current case. Lesions commonly are found on the head and neck in middle-aged to elderly patients with a slight male predominance.2

On histology, LELCS is characterized by aggregations of large, atypical epithelioid cells surrounded by a dense lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate (right quiz image). The neoplasm tends to reside within the deep dermis and/or subcutis1 without appreciable epidermal involvement (left quiz image). The atypical epithelioid cells demonstrate positive immunoreactivity for cytokeratins (right quiz image inset), p40/p63, and epithelial membrane antigen,3 and the surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate stains positively for leukocyte common antigen. The tumor histogenesis still is unknown, although an epidermal origin has been suggested given its staining pattern.2 Other investigators have postulated on an adnexal origin, citing the tumor's dermal location along with case reports describing possible glandular, sebaceous, or follicular differentiation.2,4

Treatment for LELCS can include either standard surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery, with radiation reserved for lymph node involvement, tumor recurrence, or poor surgical candidates.2,3,5 With appropriate therapy, prognosis may be considered favorable. Data from 49 LELCS patients presenting from 1988 and 2008 showed that 36 (73.5%) had no evidence of recurrence after treatment with standard surgical excision, 4 (8.2%) had local recurrence, and 6 (12.2%) developed lymph node metastasis, which led to death in 1 (2.0%) patient.2

Given the histologic similarity of LELCS to nasopharyngeal carcinoma, it is important to rule out the possibility of cutaneous metastasis, which can be done by testing for Epstein-Barr virus and performing either computed tomography imaging or comprehensive laryngoscopic examination of the head and neck region. In the current case, the patient was referred for laryngoscopy, at which time no suspicious lesions were identified. He subsequently underwent treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery, and the tumor was cleared after 2 surgical stages. At 5-month follow-up, the patient continued to do well with no signs of clinical recurrence.

Cutaneous lymphadenoma may be included in the differential diagnosis for LELCS on histopathology. This neoplasm is characterized by a well-circumscribed dermal proliferation of basaloid tumor islands within a fibrotic stroma (Figure 1). The basaloid cells may display peripheral palisading, and lymphocytes often are seen infiltrating the tumor lobules and the surrounding stroma (Figure 1 inset). Clinically, cutaneous lymphadenomas are slowly growing nodules that typically occur in young to middle-aged patients,4,6 unlike LELCS, which is more commonly observed in middle-aged to elderly patients.2