User login

Eccrine Porocarcinoma Presenting as a Recurrent Wart

Eccrine porocarcinoma (EPC), originally described by Pinkus and Mehregan1 in 1963, is an exceedingly rare sweat gland tumor most commonly seen in older patients. Fewer than 300 cases have been reported in the literature, and it is believed to represent only 0.005% to 0.01% of cutaneous malignancies.2 In the absence of established guidelines, wide local excision (WLE) has traditionally been considered the standard of treatment; however, local recurrence and nodal metastasis rates associated with WLE have been reported as high as 20%.3 More recently, a number of case reports and small case series have demonstrated higher cure rates with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), though follow-up is limited.3-5 We describe a case of EPC presenting as a recurrent wart in a 36-year-old man that was successfully treated with MMS.

Case Report

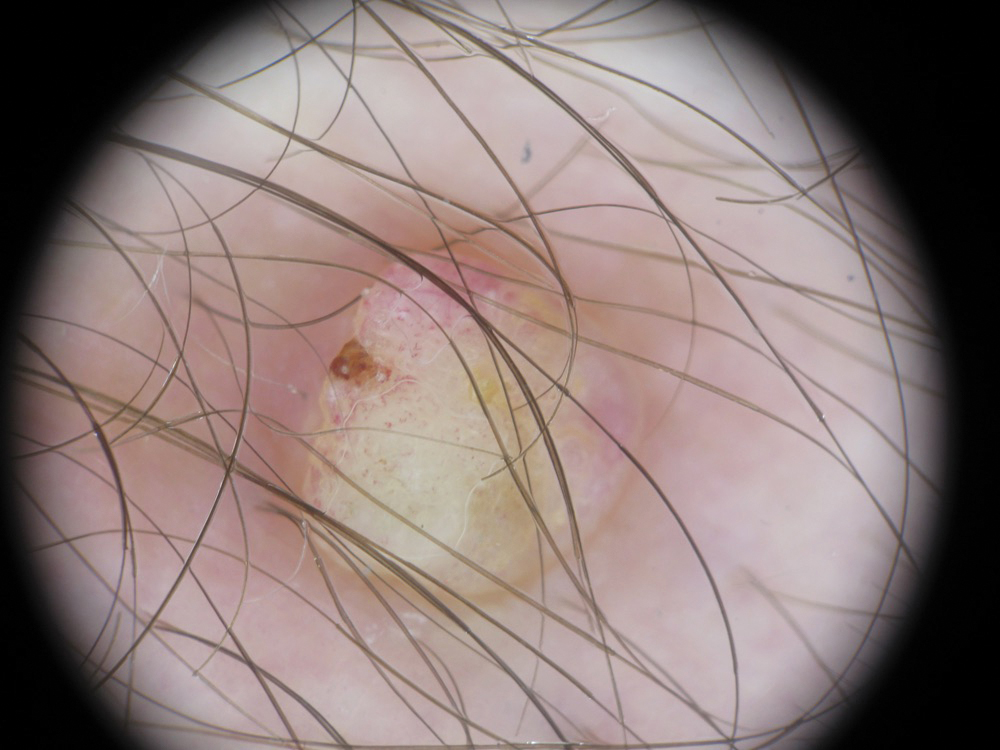

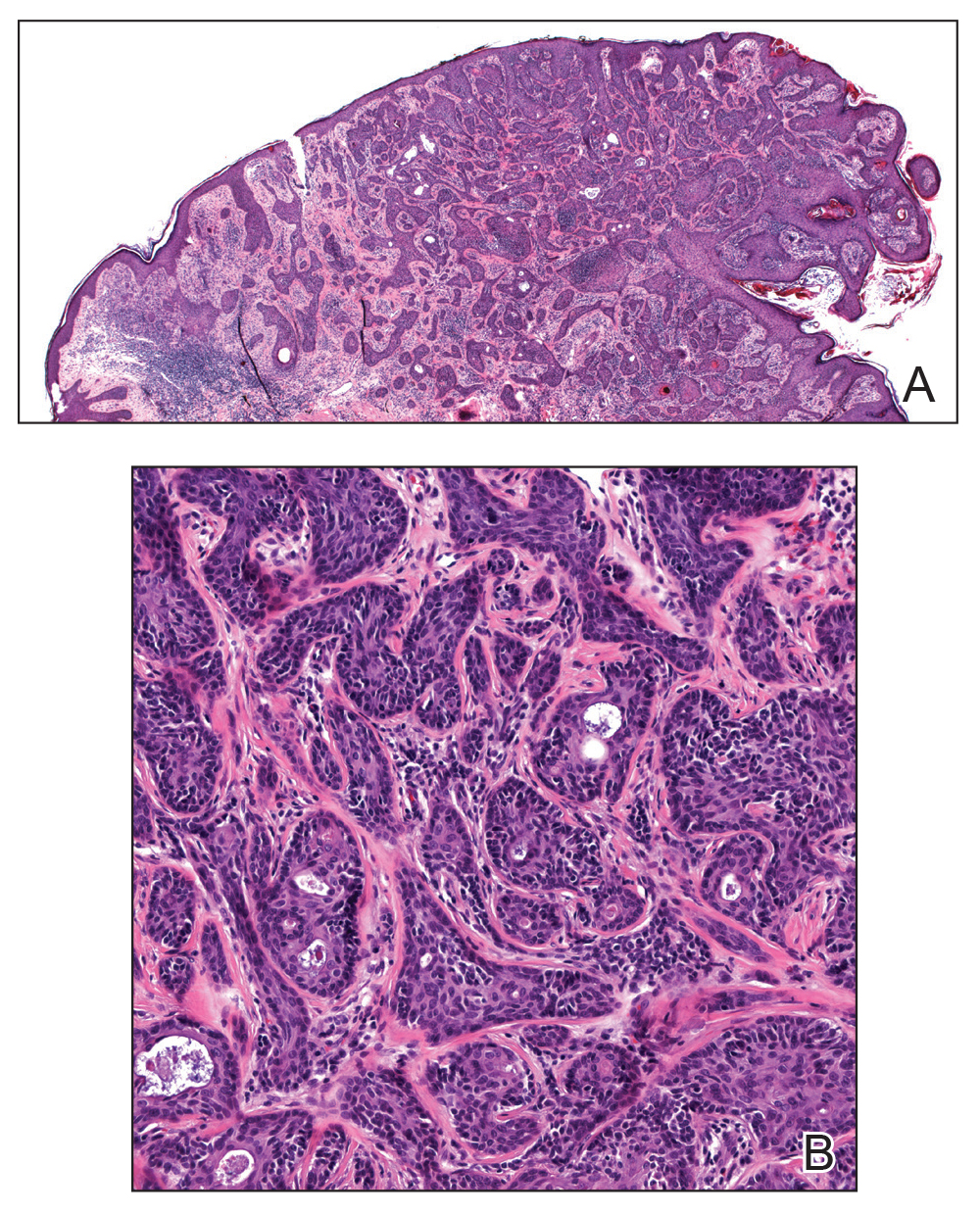

A 36-year-old man with no notable medical history presented with a 0.5×0.5-cm, asymptomatic, flesh-colored, hyperkeratotic, polypoid papule on the right medial thigh (Figure 1). The lesion was diagnosed as a wart and treated with cryotherapy by another dermatologist several years prior to presentation. Dermatoscopic examination at the current presentation showed a homogenous yellow center with a few peripheral vessels and a faint pink-tan halo (Figure 2). Our differential diagnosis included a recurrent wart, fibrosed pyogenic granuloma, irritated intradermal nevus, skin tag, and adnexal neoplasm. A shave biopsy was performed. Histopathologic analysis revealed multiple aggregations of mildly pleomorphic epithelial cells emanating from the epidermis, with many aggregations containing ductal structures (Figure 3). Rare necrotic and pyknotic cells were present, but no mitotic figures or lymphovascular invasion were identified. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen but negative for Ber-EP4. These findings were consistent with a well-differentiated EPC.

The patient was offered MMS or WLE, with or without sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB). He opted for MMS. The initial 1-cm margin taken during MMS was sufficient to achieve complete tumor extirpation, and the final 3.7×2.5-cm defect was closed primarily. The MMS debulking specimen was sent for permanent sectioning and showed a small focus of residual tumor cells, but no mitoses or lymphovascular invasion were seen. The patient was referred to surgical oncology to discuss the option of SLNB, which he ultimately declined. He also was offered regional or whole-body positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) to rule out metastatic disease, which he also declined. There was no evidence of recurrence or lymphadenopathy 19 months postoperatively.

Comment

Eccrine porocarcinoma is an exceptionally rare adnexal neoplasm that most commonly affects older adults. The average age at diagnosis is 71 years in men and 75 years in women.2 Our case is rare because of the patient’s age. Benign eccrine poromas occur most frequently on the palms, soles, axillae, and forehead where eccrine density is highest; EPC occurs most frequently on the lower extremities.6 It may arise de novo or from malignant transformation of a preexisting benign poroma. Clinically, EPC may present as an asymptomatic pink-brown papule, plaque, or nodule and may have a polypoid or verrucous appearance, as in our patient. Ulceration is common.7 The differential diagnosis often includes nodular basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, pyogenic granuloma, and seborrheic keratosis.

Histologically, EPCs are characterized by aggregations of cohesive basaloid epithelial cells forming eccrine ductal structures.2 Cellular atypia may be extremely subtle but, if present, can be helpful in differentiating malignant from benign lesions. Features of basal and squamous cell carcinoma also may be present. Definitive diagnosis is frequently based on the overall invasive architectural pattern.5 Robson et al2 examined 69 cases of EPC for high-risk histologic features and concluded that tumor depth greater than 7 mm, mitoses greater than 14 per high-power field, and the presence of lymphovascular invasion were independently predictive of mortality. Moreover, after adjusting for mitosis and depth, an infiltrative border vs a pushing border was strongly predictive of local recurrence.2 Immunohistochemical stains, although not necessary for diagnosis, may have utility as adjunctive tools. Cells lining the ducts within EPCs commonly stain positive for carcinoembryonic antigen, though glandular myoepithelial cells stain positive for S-100. Negative Ber-EP4 staining helps to differentiate EPC from basal cell carcinoma. Abnormal expression of p53 and overexpression of p16 also has been described.4

The rarity of EPC has precluded the development of any evidence-based management guidelines. Historically, the standard of care has been WLE with 2- to 3-cm margins. A review of 105 cases of EPC treated with WLE showed 20% local recurrence, 20% regional metastases, and 12% distant metastasis rates.8 Mohs micrographic surgery, which allows examination of 100% of the surgical margin vs less than 1% for WLE with the standard bread-loafing technique, might be expected to achieve higher cure rates. A review of 29 cases treated with MMS monotherapy demonstrated no local recurrences, distant metastasis, or disease-specific deaths with follow-up ranging from 19 months to 6 years.5 One case was associated with regional lymph node metastases that were treated with completion lymphadenectomy and adjuvant radiation therapy.7 The high mortality rate of patients with nodal disease has led some to recommend PET-CT and SLNB for patients with EPC. However, the prognostic value of such procedures has not been clearly defined and there is no demonstrated survival benefit for treatment of widespread disease. Our patient declined both SLNB and PET-CT, and our plan was to follow him clinically with symptom-directed imaging only.

Conclusion

Patients with EPC generally have a favorable prognosis with prompt diagnosis and complete surgical excision. Although most commonly seen in elderly patients, EPC may present in younger patients and may be clinically and histologically nondescript with little cytologic atypia. Based on a small but growing body of literature, MMS appears to be at least as effective as WLE as a primary treatment modality for EPC, while offering the advantage of tissue sparing in cosmetically or functionally important areas.

- Pinkus H, Mehregan AH. Epidermatropic eccrine carcinoma. a case combining eccrine poroma and Paget’s dermatoses. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:597-606.

- Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720.

- Tolkachjov SN, Hocker TL, Camilleri MJ, et al. Treatment of porocarcinoma with Mohs micrographic surgery: The Mayo Clinic Experience. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:745-750.

- Tidwell WJ, Mayer JE, Malone J, et al. Treatment of eccrine porocarcinoma with Mohs micrographic surgery: a cases series and literature review. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1078-1083.

- Xu YG, Aylward J, Longley BJ, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma treated by Mohs micrographic surgery: over 6-year follow-up of 12 cases and literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:685-692.

- D’Ambrosia RA, Ward H, Parry E. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the eyelid treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:4:570-571.

- Vleugels FR, Girouard SD, Schmults CD, et al. Metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma after Mohs micrographic surgery: a case report. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:188-191.

- Snow SN, Reizner GT. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the face. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:306-311.

Eccrine porocarcinoma (EPC), originally described by Pinkus and Mehregan1 in 1963, is an exceedingly rare sweat gland tumor most commonly seen in older patients. Fewer than 300 cases have been reported in the literature, and it is believed to represent only 0.005% to 0.01% of cutaneous malignancies.2 In the absence of established guidelines, wide local excision (WLE) has traditionally been considered the standard of treatment; however, local recurrence and nodal metastasis rates associated with WLE have been reported as high as 20%.3 More recently, a number of case reports and small case series have demonstrated higher cure rates with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), though follow-up is limited.3-5 We describe a case of EPC presenting as a recurrent wart in a 36-year-old man that was successfully treated with MMS.

Case Report

A 36-year-old man with no notable medical history presented with a 0.5×0.5-cm, asymptomatic, flesh-colored, hyperkeratotic, polypoid papule on the right medial thigh (Figure 1). The lesion was diagnosed as a wart and treated with cryotherapy by another dermatologist several years prior to presentation. Dermatoscopic examination at the current presentation showed a homogenous yellow center with a few peripheral vessels and a faint pink-tan halo (Figure 2). Our differential diagnosis included a recurrent wart, fibrosed pyogenic granuloma, irritated intradermal nevus, skin tag, and adnexal neoplasm. A shave biopsy was performed. Histopathologic analysis revealed multiple aggregations of mildly pleomorphic epithelial cells emanating from the epidermis, with many aggregations containing ductal structures (Figure 3). Rare necrotic and pyknotic cells were present, but no mitotic figures or lymphovascular invasion were identified. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen but negative for Ber-EP4. These findings were consistent with a well-differentiated EPC.

The patient was offered MMS or WLE, with or without sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB). He opted for MMS. The initial 1-cm margin taken during MMS was sufficient to achieve complete tumor extirpation, and the final 3.7×2.5-cm defect was closed primarily. The MMS debulking specimen was sent for permanent sectioning and showed a small focus of residual tumor cells, but no mitoses or lymphovascular invasion were seen. The patient was referred to surgical oncology to discuss the option of SLNB, which he ultimately declined. He also was offered regional or whole-body positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) to rule out metastatic disease, which he also declined. There was no evidence of recurrence or lymphadenopathy 19 months postoperatively.

Comment

Eccrine porocarcinoma is an exceptionally rare adnexal neoplasm that most commonly affects older adults. The average age at diagnosis is 71 years in men and 75 years in women.2 Our case is rare because of the patient’s age. Benign eccrine poromas occur most frequently on the palms, soles, axillae, and forehead where eccrine density is highest; EPC occurs most frequently on the lower extremities.6 It may arise de novo or from malignant transformation of a preexisting benign poroma. Clinically, EPC may present as an asymptomatic pink-brown papule, plaque, or nodule and may have a polypoid or verrucous appearance, as in our patient. Ulceration is common.7 The differential diagnosis often includes nodular basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, pyogenic granuloma, and seborrheic keratosis.

Histologically, EPCs are characterized by aggregations of cohesive basaloid epithelial cells forming eccrine ductal structures.2 Cellular atypia may be extremely subtle but, if present, can be helpful in differentiating malignant from benign lesions. Features of basal and squamous cell carcinoma also may be present. Definitive diagnosis is frequently based on the overall invasive architectural pattern.5 Robson et al2 examined 69 cases of EPC for high-risk histologic features and concluded that tumor depth greater than 7 mm, mitoses greater than 14 per high-power field, and the presence of lymphovascular invasion were independently predictive of mortality. Moreover, after adjusting for mitosis and depth, an infiltrative border vs a pushing border was strongly predictive of local recurrence.2 Immunohistochemical stains, although not necessary for diagnosis, may have utility as adjunctive tools. Cells lining the ducts within EPCs commonly stain positive for carcinoembryonic antigen, though glandular myoepithelial cells stain positive for S-100. Negative Ber-EP4 staining helps to differentiate EPC from basal cell carcinoma. Abnormal expression of p53 and overexpression of p16 also has been described.4

The rarity of EPC has precluded the development of any evidence-based management guidelines. Historically, the standard of care has been WLE with 2- to 3-cm margins. A review of 105 cases of EPC treated with WLE showed 20% local recurrence, 20% regional metastases, and 12% distant metastasis rates.8 Mohs micrographic surgery, which allows examination of 100% of the surgical margin vs less than 1% for WLE with the standard bread-loafing technique, might be expected to achieve higher cure rates. A review of 29 cases treated with MMS monotherapy demonstrated no local recurrences, distant metastasis, or disease-specific deaths with follow-up ranging from 19 months to 6 years.5 One case was associated with regional lymph node metastases that were treated with completion lymphadenectomy and adjuvant radiation therapy.7 The high mortality rate of patients with nodal disease has led some to recommend PET-CT and SLNB for patients with EPC. However, the prognostic value of such procedures has not been clearly defined and there is no demonstrated survival benefit for treatment of widespread disease. Our patient declined both SLNB and PET-CT, and our plan was to follow him clinically with symptom-directed imaging only.

Conclusion

Patients with EPC generally have a favorable prognosis with prompt diagnosis and complete surgical excision. Although most commonly seen in elderly patients, EPC may present in younger patients and may be clinically and histologically nondescript with little cytologic atypia. Based on a small but growing body of literature, MMS appears to be at least as effective as WLE as a primary treatment modality for EPC, while offering the advantage of tissue sparing in cosmetically or functionally important areas.

Eccrine porocarcinoma (EPC), originally described by Pinkus and Mehregan1 in 1963, is an exceedingly rare sweat gland tumor most commonly seen in older patients. Fewer than 300 cases have been reported in the literature, and it is believed to represent only 0.005% to 0.01% of cutaneous malignancies.2 In the absence of established guidelines, wide local excision (WLE) has traditionally been considered the standard of treatment; however, local recurrence and nodal metastasis rates associated with WLE have been reported as high as 20%.3 More recently, a number of case reports and small case series have demonstrated higher cure rates with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS), though follow-up is limited.3-5 We describe a case of EPC presenting as a recurrent wart in a 36-year-old man that was successfully treated with MMS.

Case Report

A 36-year-old man with no notable medical history presented with a 0.5×0.5-cm, asymptomatic, flesh-colored, hyperkeratotic, polypoid papule on the right medial thigh (Figure 1). The lesion was diagnosed as a wart and treated with cryotherapy by another dermatologist several years prior to presentation. Dermatoscopic examination at the current presentation showed a homogenous yellow center with a few peripheral vessels and a faint pink-tan halo (Figure 2). Our differential diagnosis included a recurrent wart, fibrosed pyogenic granuloma, irritated intradermal nevus, skin tag, and adnexal neoplasm. A shave biopsy was performed. Histopathologic analysis revealed multiple aggregations of mildly pleomorphic epithelial cells emanating from the epidermis, with many aggregations containing ductal structures (Figure 3). Rare necrotic and pyknotic cells were present, but no mitotic figures or lymphovascular invasion were identified. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen but negative for Ber-EP4. These findings were consistent with a well-differentiated EPC.

The patient was offered MMS or WLE, with or without sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB). He opted for MMS. The initial 1-cm margin taken during MMS was sufficient to achieve complete tumor extirpation, and the final 3.7×2.5-cm defect was closed primarily. The MMS debulking specimen was sent for permanent sectioning and showed a small focus of residual tumor cells, but no mitoses or lymphovascular invasion were seen. The patient was referred to surgical oncology to discuss the option of SLNB, which he ultimately declined. He also was offered regional or whole-body positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) to rule out metastatic disease, which he also declined. There was no evidence of recurrence or lymphadenopathy 19 months postoperatively.

Comment

Eccrine porocarcinoma is an exceptionally rare adnexal neoplasm that most commonly affects older adults. The average age at diagnosis is 71 years in men and 75 years in women.2 Our case is rare because of the patient’s age. Benign eccrine poromas occur most frequently on the palms, soles, axillae, and forehead where eccrine density is highest; EPC occurs most frequently on the lower extremities.6 It may arise de novo or from malignant transformation of a preexisting benign poroma. Clinically, EPC may present as an asymptomatic pink-brown papule, plaque, or nodule and may have a polypoid or verrucous appearance, as in our patient. Ulceration is common.7 The differential diagnosis often includes nodular basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, pyogenic granuloma, and seborrheic keratosis.

Histologically, EPCs are characterized by aggregations of cohesive basaloid epithelial cells forming eccrine ductal structures.2 Cellular atypia may be extremely subtle but, if present, can be helpful in differentiating malignant from benign lesions. Features of basal and squamous cell carcinoma also may be present. Definitive diagnosis is frequently based on the overall invasive architectural pattern.5 Robson et al2 examined 69 cases of EPC for high-risk histologic features and concluded that tumor depth greater than 7 mm, mitoses greater than 14 per high-power field, and the presence of lymphovascular invasion were independently predictive of mortality. Moreover, after adjusting for mitosis and depth, an infiltrative border vs a pushing border was strongly predictive of local recurrence.2 Immunohistochemical stains, although not necessary for diagnosis, may have utility as adjunctive tools. Cells lining the ducts within EPCs commonly stain positive for carcinoembryonic antigen, though glandular myoepithelial cells stain positive for S-100. Negative Ber-EP4 staining helps to differentiate EPC from basal cell carcinoma. Abnormal expression of p53 and overexpression of p16 also has been described.4

The rarity of EPC has precluded the development of any evidence-based management guidelines. Historically, the standard of care has been WLE with 2- to 3-cm margins. A review of 105 cases of EPC treated with WLE showed 20% local recurrence, 20% regional metastases, and 12% distant metastasis rates.8 Mohs micrographic surgery, which allows examination of 100% of the surgical margin vs less than 1% for WLE with the standard bread-loafing technique, might be expected to achieve higher cure rates. A review of 29 cases treated with MMS monotherapy demonstrated no local recurrences, distant metastasis, or disease-specific deaths with follow-up ranging from 19 months to 6 years.5 One case was associated with regional lymph node metastases that were treated with completion lymphadenectomy and adjuvant radiation therapy.7 The high mortality rate of patients with nodal disease has led some to recommend PET-CT and SLNB for patients with EPC. However, the prognostic value of such procedures has not been clearly defined and there is no demonstrated survival benefit for treatment of widespread disease. Our patient declined both SLNB and PET-CT, and our plan was to follow him clinically with symptom-directed imaging only.

Conclusion

Patients with EPC generally have a favorable prognosis with prompt diagnosis and complete surgical excision. Although most commonly seen in elderly patients, EPC may present in younger patients and may be clinically and histologically nondescript with little cytologic atypia. Based on a small but growing body of literature, MMS appears to be at least as effective as WLE as a primary treatment modality for EPC, while offering the advantage of tissue sparing in cosmetically or functionally important areas.

- Pinkus H, Mehregan AH. Epidermatropic eccrine carcinoma. a case combining eccrine poroma and Paget’s dermatoses. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:597-606.

- Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720.

- Tolkachjov SN, Hocker TL, Camilleri MJ, et al. Treatment of porocarcinoma with Mohs micrographic surgery: The Mayo Clinic Experience. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:745-750.

- Tidwell WJ, Mayer JE, Malone J, et al. Treatment of eccrine porocarcinoma with Mohs micrographic surgery: a cases series and literature review. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1078-1083.

- Xu YG, Aylward J, Longley BJ, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma treated by Mohs micrographic surgery: over 6-year follow-up of 12 cases and literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:685-692.

- D’Ambrosia RA, Ward H, Parry E. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the eyelid treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:4:570-571.

- Vleugels FR, Girouard SD, Schmults CD, et al. Metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma after Mohs micrographic surgery: a case report. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:188-191.

- Snow SN, Reizner GT. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the face. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:306-311.

- Pinkus H, Mehregan AH. Epidermatropic eccrine carcinoma. a case combining eccrine poroma and Paget’s dermatoses. Arch Dermatol. 1963;88:597-606.

- Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:710-720.

- Tolkachjov SN, Hocker TL, Camilleri MJ, et al. Treatment of porocarcinoma with Mohs micrographic surgery: The Mayo Clinic Experience. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:745-750.

- Tidwell WJ, Mayer JE, Malone J, et al. Treatment of eccrine porocarcinoma with Mohs micrographic surgery: a cases series and literature review. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1078-1083.

- Xu YG, Aylward J, Longley BJ, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma treated by Mohs micrographic surgery: over 6-year follow-up of 12 cases and literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:685-692.

- D’Ambrosia RA, Ward H, Parry E. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the eyelid treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:4:570-571.

- Vleugels FR, Girouard SD, Schmults CD, et al. Metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma after Mohs micrographic surgery: a case report. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:188-191.

- Snow SN, Reizner GT. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the face. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:306-311.

Practice Points

- Eccrine porocarcinoma is more common in older patients (age range, 71–75 years).

- Local recurrence and nodal metastasis are reported as high as 20% with wide local excision.

- Higher cure rates recently have been reported with Mohs micrographic surgery.

Asymptomatic Subcutaneous Nodule on the Cheek

The Diagnosis: Lymphoepitheliomalike Carcinoma of the Skin

The term lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin (LELCS) initially was proposed by Swanson et al1 in 1988 when they described 5 patients with cutaneous neoplasms histologically resembling nasopharyngeal carcinoma, also known as lymphoepithelioma. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin revealed over 60 cases of LELCS since 1988. However, unlike nasopharyngeal carcinoma, LELCS has not been associated with Epstein-Barr virus, with the exception of 1 known reported case.2 The clinical appearance of LELCS is nonspecific but usually presents as a flesh-colored to erythematous nodule, as was seen in the current case. Lesions commonly are found on the head and neck in middle-aged to elderly patients with a slight male predominance.2

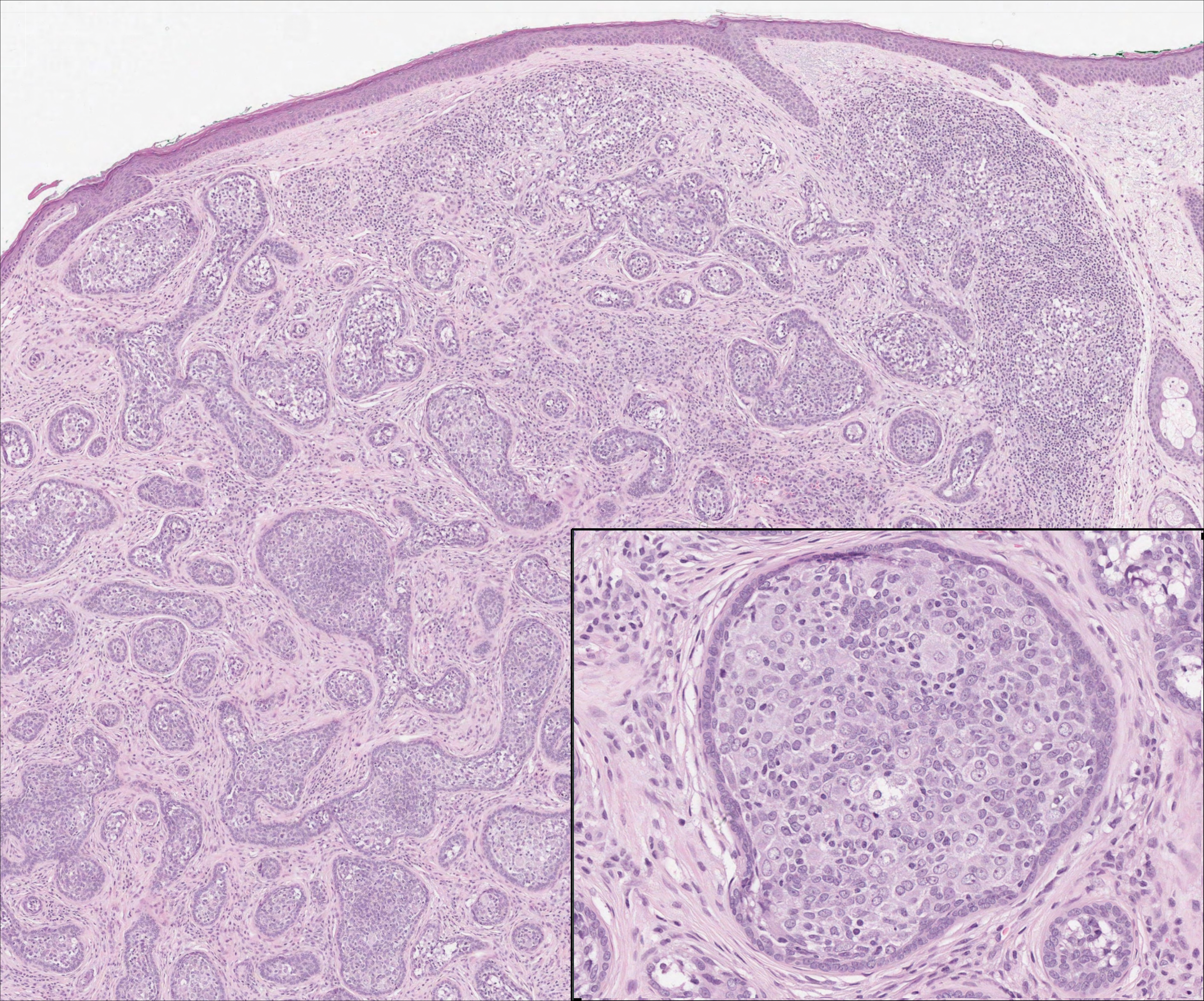

On histology, LELCS is characterized by aggregations of large, atypical epithelioid cells surrounded by a dense lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate (right quiz image). The neoplasm tends to reside within the deep dermis and/or subcutis1 without appreciable epidermal involvement (left quiz image). The atypical epithelioid cells demonstrate positive immunoreactivity for cytokeratins (right quiz image inset), p40/p63, and epithelial membrane antigen,3 and the surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate stains positively for leukocyte common antigen. The tumor histogenesis still is unknown, although an epidermal origin has been suggested given its staining pattern.2 Other investigators have postulated on an adnexal origin, citing the tumor's dermal location along with case reports describing possible glandular, sebaceous, or follicular differentiation.2,4

Treatment for LELCS can include either standard surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery, with radiation reserved for lymph node involvement, tumor recurrence, or poor surgical candidates.2,3,5 With appropriate therapy, prognosis may be considered favorable. Data from 49 LELCS patients presenting from 1988 and 2008 showed that 36 (73.5%) had no evidence of recurrence after treatment with standard surgical excision, 4 (8.2%) had local recurrence, and 6 (12.2%) developed lymph node metastasis, which led to death in 1 (2.0%) patient.2

Given the histologic similarity of LELCS to nasopharyngeal carcinoma, it is important to rule out the possibility of cutaneous metastasis, which can be done by testing for Epstein-Barr virus and performing either computed tomography imaging or comprehensive laryngoscopic examination of the head and neck region. In the current case, the patient was referred for laryngoscopy, at which time no suspicious lesions were identified. He subsequently underwent treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery, and the tumor was cleared after 2 surgical stages. At 5-month follow-up, the patient continued to do well with no signs of clinical recurrence.

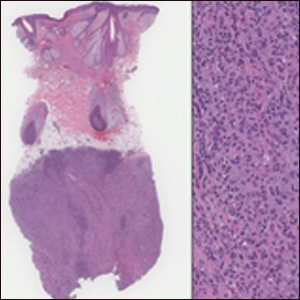

Cutaneous lymphadenoma may be included in the differential diagnosis for LELCS on histopathology. This neoplasm is characterized by a well-circumscribed dermal proliferation of basaloid tumor islands within a fibrotic stroma (Figure 1). The basaloid cells may display peripheral palisading, and lymphocytes often are seen infiltrating the tumor lobules and the surrounding stroma (Figure 1 inset). Clinically, cutaneous lymphadenomas are slowly growing nodules that typically occur in young to middle-aged patients,4,6 unlike LELCS, which is more commonly observed in middle-aged to elderly patients.2

The dense lymphocytic infiltrate seen in LELCS may obscure the neoplastic epithelioid cells and in doing so may mimic a lymphoproliferative disorder, such as lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP). Lymphomatoid papulosis is a chronic CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder consisting of recurrent crops of self-resolving papulonodules occurring on the trunk, arms, and legs. The average age of onset is in the third to fourth decades of life. Histology is dependent on the subtype; type A, the most common subtype, displays a wedge-shaped dermal infiltrate consisting of small lymphocytes (Figure 2) admixed with larger CD30+ atypical lymphocytes with prominent nucleoli (Figure 2 inset).7 Bizarre, binucleated forms resembling Reed-Sternberg cells also may be observed along with hallmark cells, which contain a horseshoe-shaped nucleus. The presence of admixed neutrophils and eosinophils also are common in type A LyP, a feature that is not characteristic of LELCS. Moreover, the atypical cells in LyP would not stain positively for epithelial markers as they would in LELCS.

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare condition that usually presents with painless cervical lymphadenopathy, typically in the first and second decades of life. Skin involvement can be seen in a small subset of extranodal cases, but cutaneous involvement alone is uncommon. On histopathology, cutaneous lesions are characterized by a dense dermal infiltrate of atypical histiocytes with vesicular nuclei and pale cytoplasm admixed with inflammatory cells, including lymphocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells (Figure 3). Intracytoplasmic inflammatory cells or emperipolesis often is appreciated (Figure 3 inset).8,9 The atypical histiocytes stain positively for S100 and negatively for CD1a.

Lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin sometimes is considered to be a poorly differentiated, inflamed variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).10 A number of features may allow distinction of a primary cutaneous SCC from LELCS; for instance, SCC is more likely to have an epidermal connection and at least focal signs of squamous differentiation,11 which can include the presence of poorly differentiated epithelial cells with mitoses (Figure 4), keratin pearls, dyskeratotic cells, or intercellular bridges.12 Moreover, SCCs have a more variable surrounding inflammatory infiltrate compared to LELCS.

- Swanson SA, Cooper PH, Mills SE, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin. Mod Pathol. 1988;1:359-365.

- Aoki R, Mitsui H, Harada K, et al. A case of lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:681-684.

- Morteza Abedi S, Salama S, Alowami S. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: case report and approach to surgical pathology sign out. Rare Tumors. 2013;5:E47.

- Requena L, Sánchez Yus E, Jiménez E, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: a light-microscopic and immunohistochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:541-548.

- Welch PQ, Williams SB, Foss RD, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of head and neck skin: a systematic analysis of 11 cases and review of literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:78-86.

- Santa Cruz DJ, Barr RJ, Headington JT. Cutaneous lymphadenoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:101-110.

- Patterson JW. Cutaneous infiltrates--lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Patterson JW, Hosler GA, eds. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 2016:1186-1189.

- Patterson JW. Cutaneous infiltrates--nonlymphoid. In: Patterson JW, Hosler GA, eds. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 2016:1158.

- Skiljo M, Garcia-Lora E, Tercedor J, et al. Purely cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Dermatology. 1995;191:49-51.

- Wang G, Bordeaux JS, Rowe DJ, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma vs inflamed squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1367-1368.

- Hall G, Duncan A, Azurdia R, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: a case with lymph node metastases at presentation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:211-215.

- Lind AC, Breer WA, Wick MR. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin with apparent origin in the epidermis--a pattern or an entity? a case report. Cancer. 1999;85:884-890.

The Diagnosis: Lymphoepitheliomalike Carcinoma of the Skin

The term lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin (LELCS) initially was proposed by Swanson et al1 in 1988 when they described 5 patients with cutaneous neoplasms histologically resembling nasopharyngeal carcinoma, also known as lymphoepithelioma. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin revealed over 60 cases of LELCS since 1988. However, unlike nasopharyngeal carcinoma, LELCS has not been associated with Epstein-Barr virus, with the exception of 1 known reported case.2 The clinical appearance of LELCS is nonspecific but usually presents as a flesh-colored to erythematous nodule, as was seen in the current case. Lesions commonly are found on the head and neck in middle-aged to elderly patients with a slight male predominance.2

On histology, LELCS is characterized by aggregations of large, atypical epithelioid cells surrounded by a dense lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate (right quiz image). The neoplasm tends to reside within the deep dermis and/or subcutis1 without appreciable epidermal involvement (left quiz image). The atypical epithelioid cells demonstrate positive immunoreactivity for cytokeratins (right quiz image inset), p40/p63, and epithelial membrane antigen,3 and the surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate stains positively for leukocyte common antigen. The tumor histogenesis still is unknown, although an epidermal origin has been suggested given its staining pattern.2 Other investigators have postulated on an adnexal origin, citing the tumor's dermal location along with case reports describing possible glandular, sebaceous, or follicular differentiation.2,4

Treatment for LELCS can include either standard surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery, with radiation reserved for lymph node involvement, tumor recurrence, or poor surgical candidates.2,3,5 With appropriate therapy, prognosis may be considered favorable. Data from 49 LELCS patients presenting from 1988 and 2008 showed that 36 (73.5%) had no evidence of recurrence after treatment with standard surgical excision, 4 (8.2%) had local recurrence, and 6 (12.2%) developed lymph node metastasis, which led to death in 1 (2.0%) patient.2

Given the histologic similarity of LELCS to nasopharyngeal carcinoma, it is important to rule out the possibility of cutaneous metastasis, which can be done by testing for Epstein-Barr virus and performing either computed tomography imaging or comprehensive laryngoscopic examination of the head and neck region. In the current case, the patient was referred for laryngoscopy, at which time no suspicious lesions were identified. He subsequently underwent treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery, and the tumor was cleared after 2 surgical stages. At 5-month follow-up, the patient continued to do well with no signs of clinical recurrence.

Cutaneous lymphadenoma may be included in the differential diagnosis for LELCS on histopathology. This neoplasm is characterized by a well-circumscribed dermal proliferation of basaloid tumor islands within a fibrotic stroma (Figure 1). The basaloid cells may display peripheral palisading, and lymphocytes often are seen infiltrating the tumor lobules and the surrounding stroma (Figure 1 inset). Clinically, cutaneous lymphadenomas are slowly growing nodules that typically occur in young to middle-aged patients,4,6 unlike LELCS, which is more commonly observed in middle-aged to elderly patients.2

The dense lymphocytic infiltrate seen in LELCS may obscure the neoplastic epithelioid cells and in doing so may mimic a lymphoproliferative disorder, such as lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP). Lymphomatoid papulosis is a chronic CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder consisting of recurrent crops of self-resolving papulonodules occurring on the trunk, arms, and legs. The average age of onset is in the third to fourth decades of life. Histology is dependent on the subtype; type A, the most common subtype, displays a wedge-shaped dermal infiltrate consisting of small lymphocytes (Figure 2) admixed with larger CD30+ atypical lymphocytes with prominent nucleoli (Figure 2 inset).7 Bizarre, binucleated forms resembling Reed-Sternberg cells also may be observed along with hallmark cells, which contain a horseshoe-shaped nucleus. The presence of admixed neutrophils and eosinophils also are common in type A LyP, a feature that is not characteristic of LELCS. Moreover, the atypical cells in LyP would not stain positively for epithelial markers as they would in LELCS.

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare condition that usually presents with painless cervical lymphadenopathy, typically in the first and second decades of life. Skin involvement can be seen in a small subset of extranodal cases, but cutaneous involvement alone is uncommon. On histopathology, cutaneous lesions are characterized by a dense dermal infiltrate of atypical histiocytes with vesicular nuclei and pale cytoplasm admixed with inflammatory cells, including lymphocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells (Figure 3). Intracytoplasmic inflammatory cells or emperipolesis often is appreciated (Figure 3 inset).8,9 The atypical histiocytes stain positively for S100 and negatively for CD1a.

Lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin sometimes is considered to be a poorly differentiated, inflamed variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).10 A number of features may allow distinction of a primary cutaneous SCC from LELCS; for instance, SCC is more likely to have an epidermal connection and at least focal signs of squamous differentiation,11 which can include the presence of poorly differentiated epithelial cells with mitoses (Figure 4), keratin pearls, dyskeratotic cells, or intercellular bridges.12 Moreover, SCCs have a more variable surrounding inflammatory infiltrate compared to LELCS.

The Diagnosis: Lymphoepitheliomalike Carcinoma of the Skin

The term lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin (LELCS) initially was proposed by Swanson et al1 in 1988 when they described 5 patients with cutaneous neoplasms histologically resembling nasopharyngeal carcinoma, also known as lymphoepithelioma. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin revealed over 60 cases of LELCS since 1988. However, unlike nasopharyngeal carcinoma, LELCS has not been associated with Epstein-Barr virus, with the exception of 1 known reported case.2 The clinical appearance of LELCS is nonspecific but usually presents as a flesh-colored to erythematous nodule, as was seen in the current case. Lesions commonly are found on the head and neck in middle-aged to elderly patients with a slight male predominance.2

On histology, LELCS is characterized by aggregations of large, atypical epithelioid cells surrounded by a dense lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate (right quiz image). The neoplasm tends to reside within the deep dermis and/or subcutis1 without appreciable epidermal involvement (left quiz image). The atypical epithelioid cells demonstrate positive immunoreactivity for cytokeratins (right quiz image inset), p40/p63, and epithelial membrane antigen,3 and the surrounding lymphocytic infiltrate stains positively for leukocyte common antigen. The tumor histogenesis still is unknown, although an epidermal origin has been suggested given its staining pattern.2 Other investigators have postulated on an adnexal origin, citing the tumor's dermal location along with case reports describing possible glandular, sebaceous, or follicular differentiation.2,4

Treatment for LELCS can include either standard surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery, with radiation reserved for lymph node involvement, tumor recurrence, or poor surgical candidates.2,3,5 With appropriate therapy, prognosis may be considered favorable. Data from 49 LELCS patients presenting from 1988 and 2008 showed that 36 (73.5%) had no evidence of recurrence after treatment with standard surgical excision, 4 (8.2%) had local recurrence, and 6 (12.2%) developed lymph node metastasis, which led to death in 1 (2.0%) patient.2

Given the histologic similarity of LELCS to nasopharyngeal carcinoma, it is important to rule out the possibility of cutaneous metastasis, which can be done by testing for Epstein-Barr virus and performing either computed tomography imaging or comprehensive laryngoscopic examination of the head and neck region. In the current case, the patient was referred for laryngoscopy, at which time no suspicious lesions were identified. He subsequently underwent treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery, and the tumor was cleared after 2 surgical stages. At 5-month follow-up, the patient continued to do well with no signs of clinical recurrence.

Cutaneous lymphadenoma may be included in the differential diagnosis for LELCS on histopathology. This neoplasm is characterized by a well-circumscribed dermal proliferation of basaloid tumor islands within a fibrotic stroma (Figure 1). The basaloid cells may display peripheral palisading, and lymphocytes often are seen infiltrating the tumor lobules and the surrounding stroma (Figure 1 inset). Clinically, cutaneous lymphadenomas are slowly growing nodules that typically occur in young to middle-aged patients,4,6 unlike LELCS, which is more commonly observed in middle-aged to elderly patients.2

The dense lymphocytic infiltrate seen in LELCS may obscure the neoplastic epithelioid cells and in doing so may mimic a lymphoproliferative disorder, such as lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP). Lymphomatoid papulosis is a chronic CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder consisting of recurrent crops of self-resolving papulonodules occurring on the trunk, arms, and legs. The average age of onset is in the third to fourth decades of life. Histology is dependent on the subtype; type A, the most common subtype, displays a wedge-shaped dermal infiltrate consisting of small lymphocytes (Figure 2) admixed with larger CD30+ atypical lymphocytes with prominent nucleoli (Figure 2 inset).7 Bizarre, binucleated forms resembling Reed-Sternberg cells also may be observed along with hallmark cells, which contain a horseshoe-shaped nucleus. The presence of admixed neutrophils and eosinophils also are common in type A LyP, a feature that is not characteristic of LELCS. Moreover, the atypical cells in LyP would not stain positively for epithelial markers as they would in LELCS.

Rosai-Dorfman disease is a rare condition that usually presents with painless cervical lymphadenopathy, typically in the first and second decades of life. Skin involvement can be seen in a small subset of extranodal cases, but cutaneous involvement alone is uncommon. On histopathology, cutaneous lesions are characterized by a dense dermal infiltrate of atypical histiocytes with vesicular nuclei and pale cytoplasm admixed with inflammatory cells, including lymphocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells (Figure 3). Intracytoplasmic inflammatory cells or emperipolesis often is appreciated (Figure 3 inset).8,9 The atypical histiocytes stain positively for S100 and negatively for CD1a.

Lymphoepitheliomalike carcinoma of the skin sometimes is considered to be a poorly differentiated, inflamed variant of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).10 A number of features may allow distinction of a primary cutaneous SCC from LELCS; for instance, SCC is more likely to have an epidermal connection and at least focal signs of squamous differentiation,11 which can include the presence of poorly differentiated epithelial cells with mitoses (Figure 4), keratin pearls, dyskeratotic cells, or intercellular bridges.12 Moreover, SCCs have a more variable surrounding inflammatory infiltrate compared to LELCS.

- Swanson SA, Cooper PH, Mills SE, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin. Mod Pathol. 1988;1:359-365.

- Aoki R, Mitsui H, Harada K, et al. A case of lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:681-684.

- Morteza Abedi S, Salama S, Alowami S. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: case report and approach to surgical pathology sign out. Rare Tumors. 2013;5:E47.

- Requena L, Sánchez Yus E, Jiménez E, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: a light-microscopic and immunohistochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:541-548.

- Welch PQ, Williams SB, Foss RD, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of head and neck skin: a systematic analysis of 11 cases and review of literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:78-86.

- Santa Cruz DJ, Barr RJ, Headington JT. Cutaneous lymphadenoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:101-110.

- Patterson JW. Cutaneous infiltrates--lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Patterson JW, Hosler GA, eds. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 2016:1186-1189.

- Patterson JW. Cutaneous infiltrates--nonlymphoid. In: Patterson JW, Hosler GA, eds. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 2016:1158.

- Skiljo M, Garcia-Lora E, Tercedor J, et al. Purely cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Dermatology. 1995;191:49-51.

- Wang G, Bordeaux JS, Rowe DJ, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma vs inflamed squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1367-1368.

- Hall G, Duncan A, Azurdia R, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: a case with lymph node metastases at presentation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:211-215.

- Lind AC, Breer WA, Wick MR. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin with apparent origin in the epidermis--a pattern or an entity? a case report. Cancer. 1999;85:884-890.

- Swanson SA, Cooper PH, Mills SE, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin. Mod Pathol. 1988;1:359-365.

- Aoki R, Mitsui H, Harada K, et al. A case of lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:681-684.

- Morteza Abedi S, Salama S, Alowami S. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: case report and approach to surgical pathology sign out. Rare Tumors. 2013;5:E47.

- Requena L, Sánchez Yus E, Jiménez E, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: a light-microscopic and immunohistochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:541-548.

- Welch PQ, Williams SB, Foss RD, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of head and neck skin: a systematic analysis of 11 cases and review of literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:78-86.

- Santa Cruz DJ, Barr RJ, Headington JT. Cutaneous lymphadenoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:101-110.

- Patterson JW. Cutaneous infiltrates--lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Patterson JW, Hosler GA, eds. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 2016:1186-1189.

- Patterson JW. Cutaneous infiltrates--nonlymphoid. In: Patterson JW, Hosler GA, eds. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. London, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 2016:1158.

- Skiljo M, Garcia-Lora E, Tercedor J, et al. Purely cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. Dermatology. 1995;191:49-51.

- Wang G, Bordeaux JS, Rowe DJ, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma vs inflamed squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1367-1368.

- Hall G, Duncan A, Azurdia R, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin: a case with lymph node metastases at presentation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:211-215.

- Lind AC, Breer WA, Wick MR. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the skin with apparent origin in the epidermis--a pattern or an entity? a case report. Cancer. 1999;85:884-890.

An 81-year-old man with history of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer presented with a subcutaneous nodule on the left cheek of 3 months' duration. The lesion was reportedly asymptomatic and measured 2.6×2.9 cm. A punch biopsy of the lesion was obtained for histopathologic evaluation.