User login

As head of the clinical laboratory at the San Juan University Hospital in Alicante, Spain, Maria Salinas, PhD, is passionate about the role she and her colleagues can play in clinical decision-making.

Her mission is the identification of “hidden diseases,” as she calls them, chronic conditions for which early identification and intervention can change the course of the illness. Her lab has been a leader over the past decade in using technology to partner with clinicians to promote the appropriate use of testing and clinical decision-making.

An example of a disease ripe for this type of intervention is rheumatoid arthritis (RA), the most common form of autoimmune arthritis, affecting around 1.3 million people in the United States. The prognosis for patients is better the earlier treatment begins.

But the

Amy S. Kehl, MD, an attending rheumatologist at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, who also sees patients at Saint John’s Physician Partners in Santa Monica, California, recommends a workup for inflammatory arthritis for patients presenting with the new onset of joint pain and swelling, primarily of small joints, although larger joints can be involved. The workup includes markers of inflammation such as an erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, which are typically elevated and can be used to monitor the progression of the disease. Similarly, the presence of anemia is consistent with RA and helpful in tracking response to treatment.

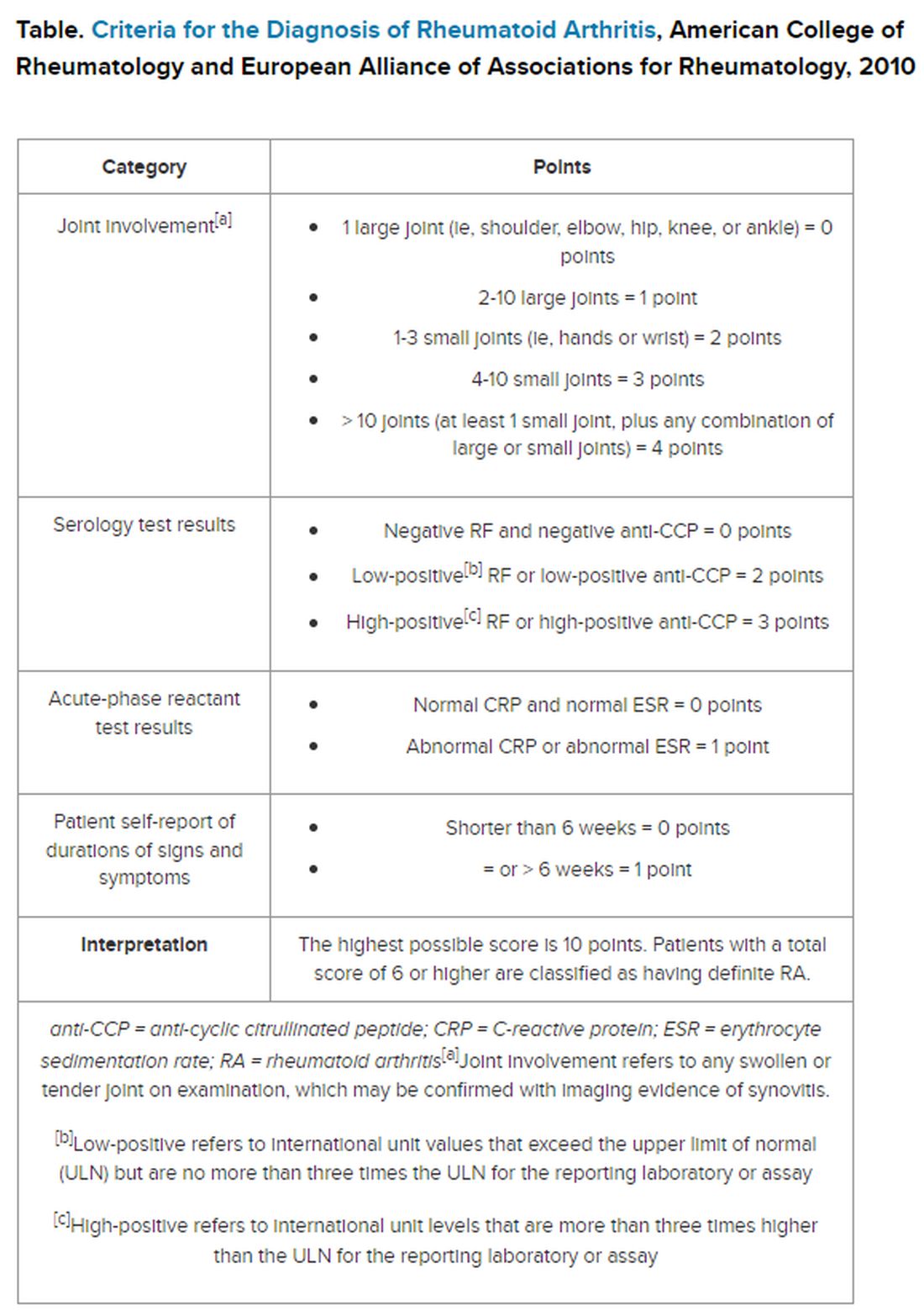

But pinning down the diagnosis requires the presence of autoimmune antibodies. Guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology require a positive result for either rheumatoid factor (RF) or anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibody to definitively determine whether a patient has RA (Table).

“Classically, I find that the primary care physicians include a rheumatoid factor, not always a CCP, and may include other antibodies, including an ANA [antinuclear antibody] test, as part of that workup,” Dr. Kehl said. The problem with that strategy is that although the RF test does detect 60%-80% of patients with RA, it is positive in many other autoimmune conditions. Although the ANA might be positive in patients with RA, it is nonspecific and does not confirm the diagnosis of RA.

Up to 50% of autoimmune antibody tests are inappropriately ordered. And for rheumatologists, that leads to unnecessary referrals of patients with musculoskeletal complaints who do not meet objective clinical criteria for joint disease.

“These tests get ordered almost reflexively, and sometimes they’re ordered as part of a panel that includes a rheumatoid factor and an ANA, and it’s not necessarily going to be a high-yield test,” Dr. Kehl said. Superfluous tests and referrals often cause unnecessary anxiety in patients, as well as drive up costs, she added.

Dr. Salinas made the same observation in her hospital lab, which also serves nine primary care centers. She documented an upward trend in orders for RF testing in her hospital lab between 2011 and 2019. Dr. Salinas also noted that the anti-CCP antibody test was not commonly requested, although it has more utility in the diagnosis. Like the RF, it detects 50%-70% of patients with RA but has 95% specificity, resulting in far fewer false-positive results.

The appearance of both RF and anti-CCP antibodies often predicts a rapid progression to clinical disease. Dr. Kehl wants symptomatic patients with positive results for both markers to be seen right away by a rheumatologist. “We do know from studies that bony erosions can develop as early as a month or months after the onset of an inflammatory arthritis,” she said.

To address this need, Dr. Salinas worked with rheumatologists and primary care clinicians to develop an algorithm that called for reflex testing of samples from patients with positive RF results (> 30 IU/mL) for anti-CCP antibodies. If the anti-CCP antibody result was > 40 IU/mL, a comment in the lab report suggested rheumatology referral. The lab turned down requests to test sample for RF if the patient had a negative result in the previous 12 months — but it would perform the test if the clinician repeated the request.

The results were encouraging, Dr. Salinas said. “The main result in this study was that we really identified more hidden cases of patients with rheumatoid arthritis,” she told this news organization.

Compared with baseline trends, during the study period from April 2019 to January 2021 her lab demonstrated:

- Reduced RF tests conducted by canceling 16% of tests ordered for patients with negative RF result in the previous 12 months

- Fewer unnecessary referrals, from 22% in the baseline period to 8% during the intervention period

- A smaller percentage of missed patients, from 21% to 16%

To be sure, pre- and post-implementation comparisons are difficult when the implementation period happens to coincide with the emergence of SARS-CoV-2.

Although fewer patients were seen and fewer lab tests were ordered overall in Alicante during the COVID-19 pandemic, the proportion of tests ordered for RF testing dropped, and all the patients identified with double positives for RF and anti-CCP antibodies were referred to rheumatology, suggesting evidence of benefit.

Dr. Kehl said the practice of using clinical decision support systems could be used in the United States. “I thought this was an important study,” she said. Electronic health records systems “have all these capabilities where we can include best practice alerts when you order a test to make sure that it’s clinically warranted and cost-effective.”

Dr. Salinas and Dr. Kehl reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

As head of the clinical laboratory at the San Juan University Hospital in Alicante, Spain, Maria Salinas, PhD, is passionate about the role she and her colleagues can play in clinical decision-making.

Her mission is the identification of “hidden diseases,” as she calls them, chronic conditions for which early identification and intervention can change the course of the illness. Her lab has been a leader over the past decade in using technology to partner with clinicians to promote the appropriate use of testing and clinical decision-making.

An example of a disease ripe for this type of intervention is rheumatoid arthritis (RA), the most common form of autoimmune arthritis, affecting around 1.3 million people in the United States. The prognosis for patients is better the earlier treatment begins.

But the

Amy S. Kehl, MD, an attending rheumatologist at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, who also sees patients at Saint John’s Physician Partners in Santa Monica, California, recommends a workup for inflammatory arthritis for patients presenting with the new onset of joint pain and swelling, primarily of small joints, although larger joints can be involved. The workup includes markers of inflammation such as an erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, which are typically elevated and can be used to monitor the progression of the disease. Similarly, the presence of anemia is consistent with RA and helpful in tracking response to treatment.

But pinning down the diagnosis requires the presence of autoimmune antibodies. Guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology require a positive result for either rheumatoid factor (RF) or anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibody to definitively determine whether a patient has RA (Table).

“Classically, I find that the primary care physicians include a rheumatoid factor, not always a CCP, and may include other antibodies, including an ANA [antinuclear antibody] test, as part of that workup,” Dr. Kehl said. The problem with that strategy is that although the RF test does detect 60%-80% of patients with RA, it is positive in many other autoimmune conditions. Although the ANA might be positive in patients with RA, it is nonspecific and does not confirm the diagnosis of RA.

Up to 50% of autoimmune antibody tests are inappropriately ordered. And for rheumatologists, that leads to unnecessary referrals of patients with musculoskeletal complaints who do not meet objective clinical criteria for joint disease.

“These tests get ordered almost reflexively, and sometimes they’re ordered as part of a panel that includes a rheumatoid factor and an ANA, and it’s not necessarily going to be a high-yield test,” Dr. Kehl said. Superfluous tests and referrals often cause unnecessary anxiety in patients, as well as drive up costs, she added.

Dr. Salinas made the same observation in her hospital lab, which also serves nine primary care centers. She documented an upward trend in orders for RF testing in her hospital lab between 2011 and 2019. Dr. Salinas also noted that the anti-CCP antibody test was not commonly requested, although it has more utility in the diagnosis. Like the RF, it detects 50%-70% of patients with RA but has 95% specificity, resulting in far fewer false-positive results.

The appearance of both RF and anti-CCP antibodies often predicts a rapid progression to clinical disease. Dr. Kehl wants symptomatic patients with positive results for both markers to be seen right away by a rheumatologist. “We do know from studies that bony erosions can develop as early as a month or months after the onset of an inflammatory arthritis,” she said.

To address this need, Dr. Salinas worked with rheumatologists and primary care clinicians to develop an algorithm that called for reflex testing of samples from patients with positive RF results (> 30 IU/mL) for anti-CCP antibodies. If the anti-CCP antibody result was > 40 IU/mL, a comment in the lab report suggested rheumatology referral. The lab turned down requests to test sample for RF if the patient had a negative result in the previous 12 months — but it would perform the test if the clinician repeated the request.

The results were encouraging, Dr. Salinas said. “The main result in this study was that we really identified more hidden cases of patients with rheumatoid arthritis,” she told this news organization.

Compared with baseline trends, during the study period from April 2019 to January 2021 her lab demonstrated:

- Reduced RF tests conducted by canceling 16% of tests ordered for patients with negative RF result in the previous 12 months

- Fewer unnecessary referrals, from 22% in the baseline period to 8% during the intervention period

- A smaller percentage of missed patients, from 21% to 16%

To be sure, pre- and post-implementation comparisons are difficult when the implementation period happens to coincide with the emergence of SARS-CoV-2.

Although fewer patients were seen and fewer lab tests were ordered overall in Alicante during the COVID-19 pandemic, the proportion of tests ordered for RF testing dropped, and all the patients identified with double positives for RF and anti-CCP antibodies were referred to rheumatology, suggesting evidence of benefit.

Dr. Kehl said the practice of using clinical decision support systems could be used in the United States. “I thought this was an important study,” she said. Electronic health records systems “have all these capabilities where we can include best practice alerts when you order a test to make sure that it’s clinically warranted and cost-effective.”

Dr. Salinas and Dr. Kehl reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

As head of the clinical laboratory at the San Juan University Hospital in Alicante, Spain, Maria Salinas, PhD, is passionate about the role she and her colleagues can play in clinical decision-making.

Her mission is the identification of “hidden diseases,” as she calls them, chronic conditions for which early identification and intervention can change the course of the illness. Her lab has been a leader over the past decade in using technology to partner with clinicians to promote the appropriate use of testing and clinical decision-making.

An example of a disease ripe for this type of intervention is rheumatoid arthritis (RA), the most common form of autoimmune arthritis, affecting around 1.3 million people in the United States. The prognosis for patients is better the earlier treatment begins.

But the

Amy S. Kehl, MD, an attending rheumatologist at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, who also sees patients at Saint John’s Physician Partners in Santa Monica, California, recommends a workup for inflammatory arthritis for patients presenting with the new onset of joint pain and swelling, primarily of small joints, although larger joints can be involved. The workup includes markers of inflammation such as an erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, which are typically elevated and can be used to monitor the progression of the disease. Similarly, the presence of anemia is consistent with RA and helpful in tracking response to treatment.

But pinning down the diagnosis requires the presence of autoimmune antibodies. Guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology require a positive result for either rheumatoid factor (RF) or anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibody to definitively determine whether a patient has RA (Table).

“Classically, I find that the primary care physicians include a rheumatoid factor, not always a CCP, and may include other antibodies, including an ANA [antinuclear antibody] test, as part of that workup,” Dr. Kehl said. The problem with that strategy is that although the RF test does detect 60%-80% of patients with RA, it is positive in many other autoimmune conditions. Although the ANA might be positive in patients with RA, it is nonspecific and does not confirm the diagnosis of RA.

Up to 50% of autoimmune antibody tests are inappropriately ordered. And for rheumatologists, that leads to unnecessary referrals of patients with musculoskeletal complaints who do not meet objective clinical criteria for joint disease.

“These tests get ordered almost reflexively, and sometimes they’re ordered as part of a panel that includes a rheumatoid factor and an ANA, and it’s not necessarily going to be a high-yield test,” Dr. Kehl said. Superfluous tests and referrals often cause unnecessary anxiety in patients, as well as drive up costs, she added.

Dr. Salinas made the same observation in her hospital lab, which also serves nine primary care centers. She documented an upward trend in orders for RF testing in her hospital lab between 2011 and 2019. Dr. Salinas also noted that the anti-CCP antibody test was not commonly requested, although it has more utility in the diagnosis. Like the RF, it detects 50%-70% of patients with RA but has 95% specificity, resulting in far fewer false-positive results.

The appearance of both RF and anti-CCP antibodies often predicts a rapid progression to clinical disease. Dr. Kehl wants symptomatic patients with positive results for both markers to be seen right away by a rheumatologist. “We do know from studies that bony erosions can develop as early as a month or months after the onset of an inflammatory arthritis,” she said.

To address this need, Dr. Salinas worked with rheumatologists and primary care clinicians to develop an algorithm that called for reflex testing of samples from patients with positive RF results (> 30 IU/mL) for anti-CCP antibodies. If the anti-CCP antibody result was > 40 IU/mL, a comment in the lab report suggested rheumatology referral. The lab turned down requests to test sample for RF if the patient had a negative result in the previous 12 months — but it would perform the test if the clinician repeated the request.

The results were encouraging, Dr. Salinas said. “The main result in this study was that we really identified more hidden cases of patients with rheumatoid arthritis,” she told this news organization.

Compared with baseline trends, during the study period from April 2019 to January 2021 her lab demonstrated:

- Reduced RF tests conducted by canceling 16% of tests ordered for patients with negative RF result in the previous 12 months

- Fewer unnecessary referrals, from 22% in the baseline period to 8% during the intervention period

- A smaller percentage of missed patients, from 21% to 16%

To be sure, pre- and post-implementation comparisons are difficult when the implementation period happens to coincide with the emergence of SARS-CoV-2.

Although fewer patients were seen and fewer lab tests were ordered overall in Alicante during the COVID-19 pandemic, the proportion of tests ordered for RF testing dropped, and all the patients identified with double positives for RF and anti-CCP antibodies were referred to rheumatology, suggesting evidence of benefit.

Dr. Kehl said the practice of using clinical decision support systems could be used in the United States. “I thought this was an important study,” she said. Electronic health records systems “have all these capabilities where we can include best practice alerts when you order a test to make sure that it’s clinically warranted and cost-effective.”

Dr. Salinas and Dr. Kehl reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.