User login

Certain species of anaerobic bacteria have been linked to dramatic increases in colorectal cancer (CRC), often within a year of infection, although whether or not the bacteria are causal has yet to be determined, say Danish researchers.

“We are not convinced that all the bacteria are directly involved in CRC development — they could just be innocent bystanders that invade the blood stream when the cancer [itself] has caused a breach in the intestinal wall,” lead author Ulrik Justesen, MD, Odense University Hospital, Denmark, told Medscape Medical News in an email.

“But an algorithm for colonoscopy based on the [infecting] species, which could then be supplemented with specific characteristics [of the bacteria] along with age, is certainly a realistic perspective,” he added.

The study was to have be presented at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ECCMID) in Paris, France, but the conference was canceled due to COVID-19.

Another study suggesting a link between bacteria and CRC was published earlier this year in Nature, as reported at the time by Medscape Medical News. That study, from the Netherlands, suggests that a strain of Escherichia coli may be involved in the development of CRC.

Population-Based Study

The latest study from Denmark was a population-based study involving over 2 million people.

From this large cohort, blood culture data from the years 2007 and 2016 were analyzed.

“We combined blood culture data with the national register for colorectal cancer — the Danish Colorectal Cancer Group Database — and identified incident CRC after bacteraemia,” the investigators state.

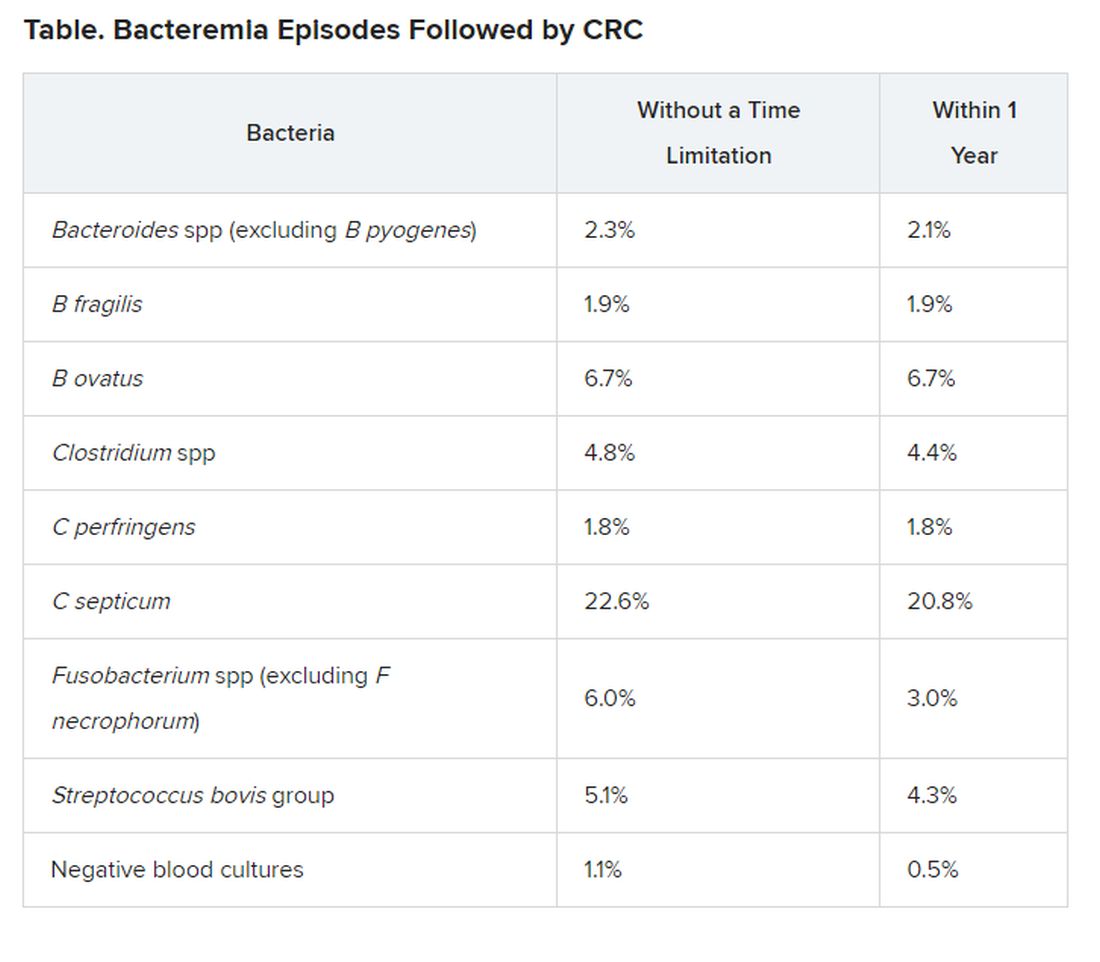

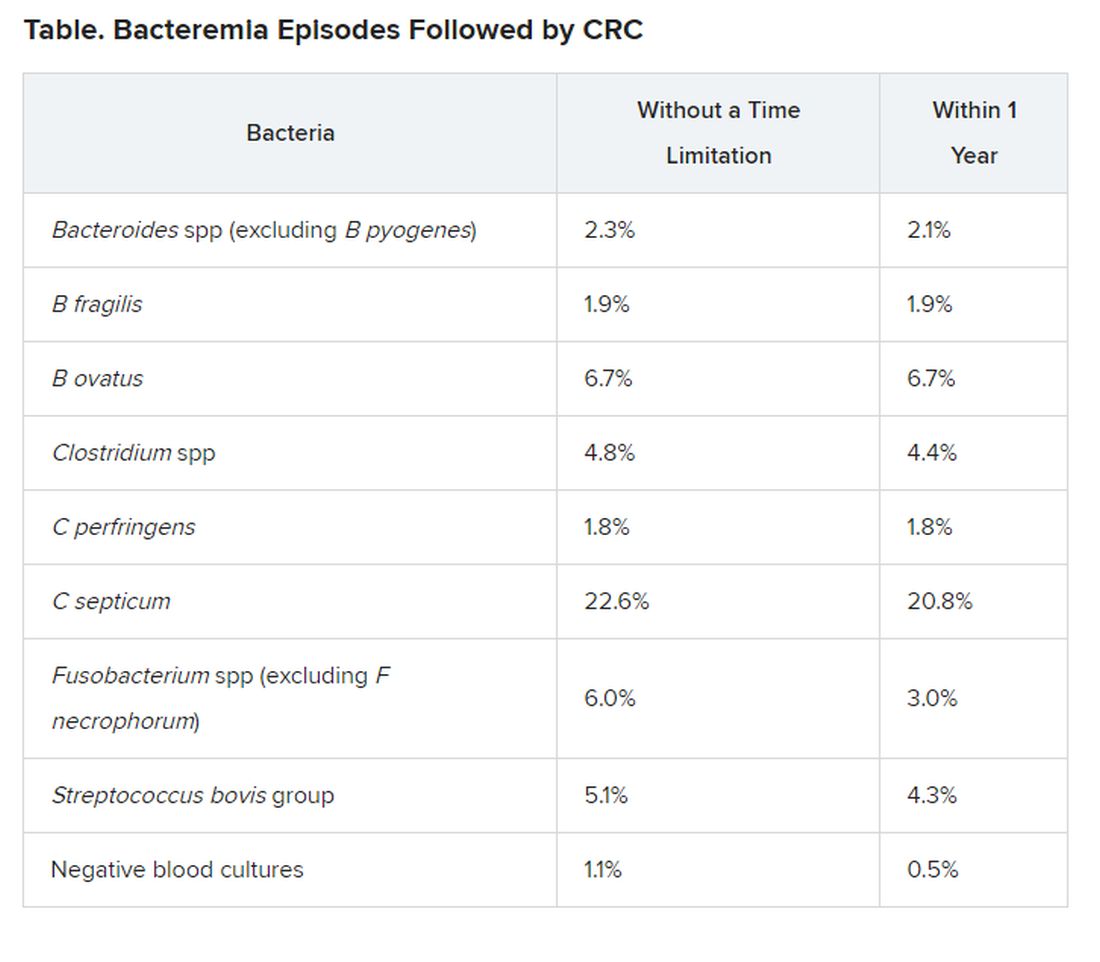

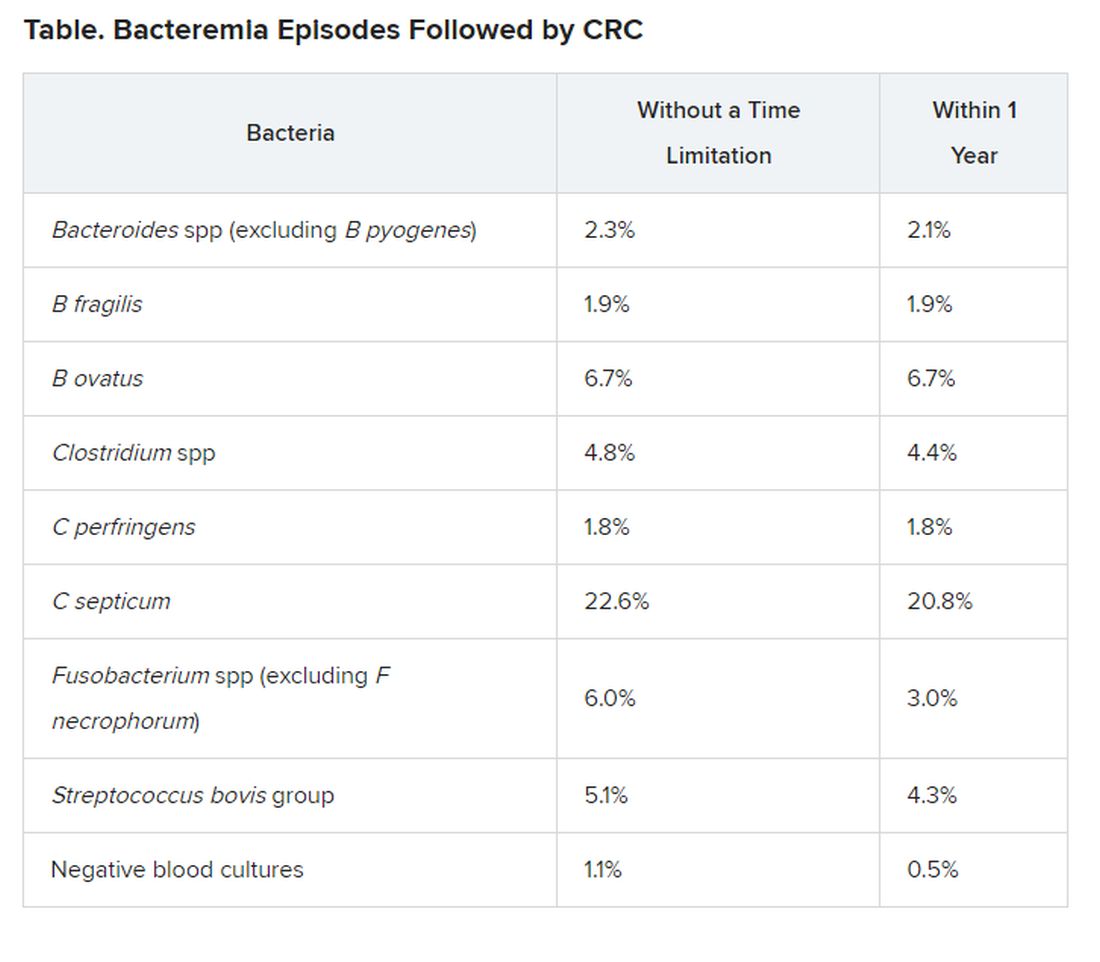

The risk for incident CRC was investigated specifically for the anaerobic bacteria Bacteroides spp, Clostridium spp, and Fusobacterium spp.

Incident rates were then compared to those from nonanaerobic bacteria, including the Streptococcus bovis group, Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus, as well as from negative blood samples.

“We included 45,760 bacteraemia episodes, of which 492 or 1.1% were diagnosed with CRC after the bacteraemia; 241 ― 0.5% ― within 1 year,” the researchers report.

The risk for CRC was notably increased in association with most anaerobic species, compared with negative blood cultures and with E coli and S aureus cultures, for which the risk was similar to that of negative blood cultures.

For example, infection with C septicum was associated with a 42 times greater risk for CRC within 1 year of infection and a 21 times greater risk overall with no time limitation.

Infection with B ovatus was linked to a 13 times greater risk for CRC within 1 year and a six times greater risk overall with no time limitation.

Justesen noted that their group will now focus on specific bacteria from cancer patients in an effort to identify characteristics of the bacteria that could be implicated in cancer development.

“If this is the case, it could be of great importance when it comes to screening and treatment of CRC,” he said in a statement.

For example, if there was evidence that a patient had been infected with C septicum, the anaerobic species associated with the highest risk for CRC within 1 year of infection, “we would immediately inform the treating physician about this risk and that the [patient] should be investigated further,” he told Medscape Medical News.

Justesen also noted that if there was evidence that a patient was infected with any of these high-risk bacteria and the patient was elderly, “then it would definitely be worth screening the patient for CRC,” he said. However, more research is needed before specific recommendations can be made for CRC screening in the context of any anaerobic infection, he stressed.

Justesen has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Certain species of anaerobic bacteria have been linked to dramatic increases in colorectal cancer (CRC), often within a year of infection, although whether or not the bacteria are causal has yet to be determined, say Danish researchers.

“We are not convinced that all the bacteria are directly involved in CRC development — they could just be innocent bystanders that invade the blood stream when the cancer [itself] has caused a breach in the intestinal wall,” lead author Ulrik Justesen, MD, Odense University Hospital, Denmark, told Medscape Medical News in an email.

“But an algorithm for colonoscopy based on the [infecting] species, which could then be supplemented with specific characteristics [of the bacteria] along with age, is certainly a realistic perspective,” he added.

The study was to have be presented at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ECCMID) in Paris, France, but the conference was canceled due to COVID-19.

Another study suggesting a link between bacteria and CRC was published earlier this year in Nature, as reported at the time by Medscape Medical News. That study, from the Netherlands, suggests that a strain of Escherichia coli may be involved in the development of CRC.

Population-Based Study

The latest study from Denmark was a population-based study involving over 2 million people.

From this large cohort, blood culture data from the years 2007 and 2016 were analyzed.

“We combined blood culture data with the national register for colorectal cancer — the Danish Colorectal Cancer Group Database — and identified incident CRC after bacteraemia,” the investigators state.

The risk for incident CRC was investigated specifically for the anaerobic bacteria Bacteroides spp, Clostridium spp, and Fusobacterium spp.

Incident rates were then compared to those from nonanaerobic bacteria, including the Streptococcus bovis group, Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus, as well as from negative blood samples.

“We included 45,760 bacteraemia episodes, of which 492 or 1.1% were diagnosed with CRC after the bacteraemia; 241 ― 0.5% ― within 1 year,” the researchers report.

The risk for CRC was notably increased in association with most anaerobic species, compared with negative blood cultures and with E coli and S aureus cultures, for which the risk was similar to that of negative blood cultures.

For example, infection with C septicum was associated with a 42 times greater risk for CRC within 1 year of infection and a 21 times greater risk overall with no time limitation.

Infection with B ovatus was linked to a 13 times greater risk for CRC within 1 year and a six times greater risk overall with no time limitation.

Justesen noted that their group will now focus on specific bacteria from cancer patients in an effort to identify characteristics of the bacteria that could be implicated in cancer development.

“If this is the case, it could be of great importance when it comes to screening and treatment of CRC,” he said in a statement.

For example, if there was evidence that a patient had been infected with C septicum, the anaerobic species associated with the highest risk for CRC within 1 year of infection, “we would immediately inform the treating physician about this risk and that the [patient] should be investigated further,” he told Medscape Medical News.

Justesen also noted that if there was evidence that a patient was infected with any of these high-risk bacteria and the patient was elderly, “then it would definitely be worth screening the patient for CRC,” he said. However, more research is needed before specific recommendations can be made for CRC screening in the context of any anaerobic infection, he stressed.

Justesen has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Certain species of anaerobic bacteria have been linked to dramatic increases in colorectal cancer (CRC), often within a year of infection, although whether or not the bacteria are causal has yet to be determined, say Danish researchers.

“We are not convinced that all the bacteria are directly involved in CRC development — they could just be innocent bystanders that invade the blood stream when the cancer [itself] has caused a breach in the intestinal wall,” lead author Ulrik Justesen, MD, Odense University Hospital, Denmark, told Medscape Medical News in an email.

“But an algorithm for colonoscopy based on the [infecting] species, which could then be supplemented with specific characteristics [of the bacteria] along with age, is certainly a realistic perspective,” he added.

The study was to have be presented at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ECCMID) in Paris, France, but the conference was canceled due to COVID-19.

Another study suggesting a link between bacteria and CRC was published earlier this year in Nature, as reported at the time by Medscape Medical News. That study, from the Netherlands, suggests that a strain of Escherichia coli may be involved in the development of CRC.

Population-Based Study

The latest study from Denmark was a population-based study involving over 2 million people.

From this large cohort, blood culture data from the years 2007 and 2016 were analyzed.

“We combined blood culture data with the national register for colorectal cancer — the Danish Colorectal Cancer Group Database — and identified incident CRC after bacteraemia,” the investigators state.

The risk for incident CRC was investigated specifically for the anaerobic bacteria Bacteroides spp, Clostridium spp, and Fusobacterium spp.

Incident rates were then compared to those from nonanaerobic bacteria, including the Streptococcus bovis group, Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus, as well as from negative blood samples.

“We included 45,760 bacteraemia episodes, of which 492 or 1.1% were diagnosed with CRC after the bacteraemia; 241 ― 0.5% ― within 1 year,” the researchers report.

The risk for CRC was notably increased in association with most anaerobic species, compared with negative blood cultures and with E coli and S aureus cultures, for which the risk was similar to that of negative blood cultures.

For example, infection with C septicum was associated with a 42 times greater risk for CRC within 1 year of infection and a 21 times greater risk overall with no time limitation.

Infection with B ovatus was linked to a 13 times greater risk for CRC within 1 year and a six times greater risk overall with no time limitation.

Justesen noted that their group will now focus on specific bacteria from cancer patients in an effort to identify characteristics of the bacteria that could be implicated in cancer development.

“If this is the case, it could be of great importance when it comes to screening and treatment of CRC,” he said in a statement.

For example, if there was evidence that a patient had been infected with C septicum, the anaerobic species associated with the highest risk for CRC within 1 year of infection, “we would immediately inform the treating physician about this risk and that the [patient] should be investigated further,” he told Medscape Medical News.

Justesen also noted that if there was evidence that a patient was infected with any of these high-risk bacteria and the patient was elderly, “then it would definitely be worth screening the patient for CRC,” he said. However, more research is needed before specific recommendations can be made for CRC screening in the context of any anaerobic infection, he stressed.

Justesen has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.