User login

Evidence of human exposure to mercury dates as far back as the Egyptians in 1500

Mercury release in the environment primarily is a function of human activity, including coal-fired power plants, residential heating, and mining.9,10 Mercury from these sources is commonly found in the sediment of lakes and bays, where it is enzymatically converted to methylmercury by aquatic microorganisms; subsequent food chain biomagnification results in elevated mercury levels in apex predators. Substantial release of mercury into the environment also can be attributed to health care facilities from their use of thermometers containing 0.5 to 3 g of elemental mercury,11 blood pressure monitors, and medical waste incinerators.5

Mercury has been reported as the second most common cause of heavy metal poisoning after lead.12 Standards from the US Food and Drug Administration dictate that methylmercury levels in fish and wheat products must not exceed 1 ppm.13 Most plant and animal food sources contain methylmercury at levels between 0.0001 and 0.01 ppm; mercury concentrations are especially high in tuna, averaging 0.4 ppm, while larger predatory fish contain levels in excess of 1 ppm.14 The use of mercury-containing cosmetic products also presents a substantial exposure risk to consumers.5,10 In one study, 3.3% of skin-lightening creams and soaps purchased within the United States contained concentrations of mercury exceeding 1000 ppm.15

We describe a case of mercury toxicity resulting from intentional injection of liquid mercury into the right antecubital fossa in a suicide attempt.

Case Report

A 31-year-old woman presented to the family practice center for evaluation of a firm stained area on the skin of the right arm. She reported increasing anxiety, depression, tremors, irritability, and difficulty concentrating over the last 6 months. She denied headache and joint or muscle pain. Four years earlier, she had broken apart a thermometer and injected approximately 0.7 mL of its contents into the right arm in a suicide attempt. She intended to inject the thermometer’s contents directly into a vein, but the material instead entered the surrounding tissue. She denied notable pain or itching overlying the injection site. Her medications included aripiprazole and buspirone. She noted that she smoked half a pack of cigarettes per day and had a history of methamphetamine abuse. She was homeless and unemployed. Physical examination revealed an anxious tremulous woman with an erythematous to bluish gray, firm plaque on the right antecubital fossa (Figure 1). There were no notable tremors and no gait disturbance.

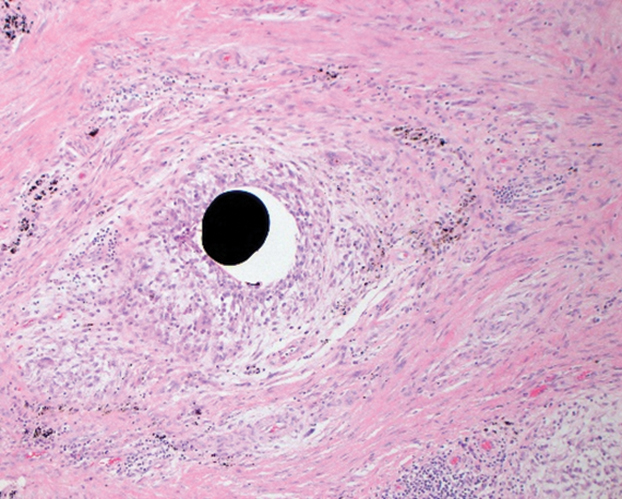

Her blood mercury level was greater than 100 µg/L and urine mercury was 477 µg/g (reference ranges, 1–8 μg/L and 4–5 μg/L, respectively). A radiograph of the right elbow area revealed scattered punctate foci of increased density within or overlying the anterolateral elbow soft tissues. She was diagnosed with mercury granuloma causing chronic mercury elevation. She underwent excision of the granuloma (Figure 2) with endovascular surgery via an elliptical incision. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Comment

Elemental mercury is a silver liquid at room temperature that spontaneously evaporates to form mercury vapor, an invisible, odorless, toxic gas. Accidental cutaneous exposure typically is safely managed by washing exposed skin with soap and water,16 though there is a potential risk for systemic absorption, especially when the skin is inflamed. When metallic mercury is subcutaneously injected, it is advised to promptly excise all subcutaneous areas containing mercury, regardless of any symptoms of systemic toxicity. Patients should subsequently be monitored for signs of both central nervous system (CNS) and renal deficits, undergo chelation therapy when systemic effects are apparent, and finally receive psychiatric consultation and treatment when necessary.17

Inorganic mercury compounds are formed when elemental mercury combines with sulfur or oxygen and often take the form of mercury salts, which appear as white crystals.16 These salts occur naturally in the environment and are used in pesticides, antiseptics, and skin-lightening creams and soaps.18

Methylmercury is a highly toxic, organic compound that is capable of crossing the placental and blood-brain barriers. It is the most common organic mercury compound found in the environment.16 Most humans have trace amounts of methylmercury in their bodies, typically as a result of consuming seafood.5

Exposure to mercury most commonly occurs through chronic consumption of methylmercury in seafood or acute inhalation of elemental mercury vapors.9 Iatrogenic cases of mercury exposure via injection also have been reported in the literature, including a case resulting in acute poisoning due to peritoneal lavage with mercury bichloride.19 Acute mercury-induced pulmonary damage typically resolves completely. However, there have been reported cases of exposure progressing to interstitial emphysema, pneumatocele, pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, interstitial fibrosis, and chronic respiratory insufficiency, with examples of fatal acute respiratory distress syndrome being reported.5,16,20 Although individuals who inhale mercury vapors initially may be unaware of exposure due to little upper airway irritation, symptoms following an initial acute exposure may include ptyalism, a metallic taste, dysphagia, enteritis, diarrhea, nausea, renal damage, and CNS effects.16 Additionally, exposure may lead to confusion with signs and symptoms of metal fume fever, including shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain, stomatitis, lethargy, and vomiting.20

Chronic exposure to mercury vapor can result in accumulation of mercury in the body, leading to neuropsychiatric, dermatologic, oropharyngeal, and renal manifestations. Sore throat, fever, headache, fatigue, dyspnea, chest pain, and pneumonitis are common.16 Typically, low-level exposure to elemental mercury does not lead to long-lasting health effects. However, individuals exposed to high-level elemental mercury vapors may require hospitalization. Treatment of acute mercury poisoning consists of removing the source of exposure, followed by cardiopulmonary support.16

Specific assays for mercury levels in blood and urine are useful to assess the level of exposure and risk to the patient. Blood mercury concentrations of 20 µg/L or below are considered within reference range; however, once blood and urine concentrations of mercury exceed 100 µg/L, clinical signs of acute mercury poisoning typically manifest.21 Chest radiographs can reveal pulmonary damage, while complete blood cell count, metabolic panel, and urinalysis can assess damage to other organs. Neuropsychiatric testing and nerve conduction studies may provide objective evidence of CNS toxicity. Assays for N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase can provide an indication of early renal tubular dysfunction.16

Elemental mercury is not absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, posing minimal risk for acute toxicity from ingestion. Generally, less than 10% of ingested inorganic mercury is absorbed from the gut, while elemental mercury is nonabsorbable.10 If an individual ingests a large amount of mercury, it may persist in the gastrointestinal tract for an extended period. Mercury is radiopaque, and abdominal radiographs should be obtained in all cases of ingestion.16

Mercury is toxic to the CNS and peripheral nervous system, resulting in erethism mercurialis, a constellation of neuropsychologic signs and symptoms including restlessness, irritability, insomnia, emotional lability, difficulty concentrating, and impaired memory. In severe cases, delirium and psychosis may develop. Other CNS effects include tremors, paresthesia, dysarthria, neuromuscular changes, headaches, polyneuropathy, and cerebellar ataxia, as well as ophthalmologic and audiologic impairment.5,16

Upon inhalation exposure, patients with respiratory concerns should be given oxygen. Bronchospasms are treated with bronchodilators; however, if multiple chemical exposures are suspected, bronchial-sensitizing agents may pose additional risks. Corticosteroids and antibiotics have been recommended for treatment of chemical pneumonitis, but their efficacy has not been substantiated.16

Skin reactions associated with skin contact to elemental mercury are rare. However, hives and dermatitis have been observed following accidental contact with inorganic mercury compounds.5 Manifestation in children chronically exposed to mercury includes a nonallergic hypersensitivity (acrodynia),5,17 which is characterized by pain and dusky pink discoloration in the hands and feet, most often seen in children chronically exposed to mercury absorbed from vapor inhalation or cutaneous exposure.16

Renal conditions associated with acute inhalation of elemental mercury vapor include proteinuria, nephrotic syndrome, temporary tubular dysfunction, acute tubular necrosis, and oliguric renal failure.16 Chronic exposure to inorganic mercury compounds also has been reported to cause renal damage.5 Chelation therapy should be performed for any symptomatic patient with a clear history of acute elemental mercury exposure.16 The most frequently used chelation agent in cases of acute inorganic mercury exposures is dimercaprol. In rare cases of mercury intoxication, hemodialysis is required in the treatment of renal failure and to expedite removal of dimercaprol-mercury complexes.16

Cardiovascular symptoms associated with acute inhalation of high levels of elemental mercury include tachycardia and hypertension.16 Increases in blood pressure, palpitations, and heart rate also have been observed in instances of acute elemental mercury exposure. Studies show that exposure to mercury increases both the risk for acute myocardial infarction as well as death from coronary heart and cardiovascular diseases.5

Conclusion

Mercury poisoning presents with varied neuropsychologic signs and symptoms. Our case provides insight into a unique route of exposure for mercury toxicity. In addition to the unusual presentation of a mercury granuloma, our case illustrates how surgical techniques can aid in removal of cutaneous reservoirs in the setting of percutaneous exposure.

- History of mercury. Government of Canada website. Modified April 26, 2010. Accessed March 11, 2021. https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/pollutants/mercury-environment/about/history.html

- Dartmouth Toxic Metals Superfund Research Program website. Accessed March 11, 2021. https://sites.dartmouth.edu/toxmetal/

- Norn S, Permin H, Kruse E, et al. Mercury—a major agent in the history of medicine and alchemy [in Danish]. Dan Medicinhist Arbog. 2008;36:21-40.

- Waldron HA. Did the Mad Hatter have mercury poisoning? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;287:1961.

- Poulin J, Gibb H. Mercury: assessing the environmental burden of disease at national and local levels. WHO Environmental Burden of Disease Series No. 16. World Health Organization; 2008.

- Charcot JM. Clinical lectures of the diseases of the nervous system. In: Kinnier Wilson SA. The Landmark Library of Neurology and Neurosurgery. Gryphon Editions; 1994:186.

- Kinnier Wilson SA. Neurology. In: Kinnier Wilson SA. The Landmark Library of Neurology and Neurosurgery. Gryphon Editions; 1994:739-740.

- Harada M. Minamata disease: methylmercury poisoning in Japan caused by environmental pollution. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1995;25:1-24.

- Mercury and health. World Health Organization website. Updated March 31, 2017. Accessed March 12, 2021. http://www.whoint/mediacentre/factsheets/fs361/en/

- Olson DA. Mercury toxicity. Updated November 5, 2018. Accessed March 12, 2021.http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1175560-overview

- Mercury thermometers. Environmental Protection Agency website. Updated June 26, 2018. https://www.epa.gov/mercury/mercury-thermometers

- Jao-Tan C, Pope E. Cutaneous poisoning syndromes in children: a review. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18:410-416.

- US Department of Health and Human Services: Public Health Service Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Toxicological profile for mercury: regulations and advisories. Published March 1999. Accessed March 23, 2021. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp46.pdf

- US Food and Drug Administration. Mercury levels in commercial fish and shellfish (1990-2012). Updated October 25, 2017. Accessed March 16, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/food/metals-and-your-food/mercury-levels-commercial-fish-and-shellfish-1990-2012

- Hamann CR, Boonchai W, Wen L, et al. Spectrometric analysis of mercury content in 549 skin-lightening products: is mercury toxicity a hidden global health hazard? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:281-287.e3.

- Mercury. Managing Hazardous Materials Incidents. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry website. Accessed March 16, 2021. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/MHMI/mmg46.pdf

- Krohn IT, Solof A, Mobini J, et al. Subcutaneous injection of metallic mercury. JAMA. 1980;243:548-549.

- Lai O, Parsi KK, Wu D, et al. Mercury toxicity presenting acrodynia and a papulovesicular eruption in a 5-year-old girl. Dermatol Online J. 2016;16;22:13030/qt6444r7nc.

- Dolianiti M, Tasiopoulou K, Kalostou A, et al. Mercury bichloride iatrogenic poisoning: a case report. J Clin Toxicol. 2016;6:2. doi:10.4172/2161-0495.1000290

- Broussard LA, Hammett-Stabler CA, Winecker RE, et al. The toxicology of mercury. Lab Med. 2002;33:614-625. doi:10.1309/5HY1-V3NE-2LFL-P9MT

- Byeong-Jin Y, Byoung-Gwon K, Man-Joong J, et al. Evaluation of mercury exposure levels, clinical diagnosis and treatment for mercury intoxication. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2016;28:5.

Evidence of human exposure to mercury dates as far back as the Egyptians in 1500

Mercury release in the environment primarily is a function of human activity, including coal-fired power plants, residential heating, and mining.9,10 Mercury from these sources is commonly found in the sediment of lakes and bays, where it is enzymatically converted to methylmercury by aquatic microorganisms; subsequent food chain biomagnification results in elevated mercury levels in apex predators. Substantial release of mercury into the environment also can be attributed to health care facilities from their use of thermometers containing 0.5 to 3 g of elemental mercury,11 blood pressure monitors, and medical waste incinerators.5

Mercury has been reported as the second most common cause of heavy metal poisoning after lead.12 Standards from the US Food and Drug Administration dictate that methylmercury levels in fish and wheat products must not exceed 1 ppm.13 Most plant and animal food sources contain methylmercury at levels between 0.0001 and 0.01 ppm; mercury concentrations are especially high in tuna, averaging 0.4 ppm, while larger predatory fish contain levels in excess of 1 ppm.14 The use of mercury-containing cosmetic products also presents a substantial exposure risk to consumers.5,10 In one study, 3.3% of skin-lightening creams and soaps purchased within the United States contained concentrations of mercury exceeding 1000 ppm.15

We describe a case of mercury toxicity resulting from intentional injection of liquid mercury into the right antecubital fossa in a suicide attempt.

Case Report

A 31-year-old woman presented to the family practice center for evaluation of a firm stained area on the skin of the right arm. She reported increasing anxiety, depression, tremors, irritability, and difficulty concentrating over the last 6 months. She denied headache and joint or muscle pain. Four years earlier, she had broken apart a thermometer and injected approximately 0.7 mL of its contents into the right arm in a suicide attempt. She intended to inject the thermometer’s contents directly into a vein, but the material instead entered the surrounding tissue. She denied notable pain or itching overlying the injection site. Her medications included aripiprazole and buspirone. She noted that she smoked half a pack of cigarettes per day and had a history of methamphetamine abuse. She was homeless and unemployed. Physical examination revealed an anxious tremulous woman with an erythematous to bluish gray, firm plaque on the right antecubital fossa (Figure 1). There were no notable tremors and no gait disturbance.

Her blood mercury level was greater than 100 µg/L and urine mercury was 477 µg/g (reference ranges, 1–8 μg/L and 4–5 μg/L, respectively). A radiograph of the right elbow area revealed scattered punctate foci of increased density within or overlying the anterolateral elbow soft tissues. She was diagnosed with mercury granuloma causing chronic mercury elevation. She underwent excision of the granuloma (Figure 2) with endovascular surgery via an elliptical incision. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Comment

Elemental mercury is a silver liquid at room temperature that spontaneously evaporates to form mercury vapor, an invisible, odorless, toxic gas. Accidental cutaneous exposure typically is safely managed by washing exposed skin with soap and water,16 though there is a potential risk for systemic absorption, especially when the skin is inflamed. When metallic mercury is subcutaneously injected, it is advised to promptly excise all subcutaneous areas containing mercury, regardless of any symptoms of systemic toxicity. Patients should subsequently be monitored for signs of both central nervous system (CNS) and renal deficits, undergo chelation therapy when systemic effects are apparent, and finally receive psychiatric consultation and treatment when necessary.17

Inorganic mercury compounds are formed when elemental mercury combines with sulfur or oxygen and often take the form of mercury salts, which appear as white crystals.16 These salts occur naturally in the environment and are used in pesticides, antiseptics, and skin-lightening creams and soaps.18

Methylmercury is a highly toxic, organic compound that is capable of crossing the placental and blood-brain barriers. It is the most common organic mercury compound found in the environment.16 Most humans have trace amounts of methylmercury in their bodies, typically as a result of consuming seafood.5

Exposure to mercury most commonly occurs through chronic consumption of methylmercury in seafood or acute inhalation of elemental mercury vapors.9 Iatrogenic cases of mercury exposure via injection also have been reported in the literature, including a case resulting in acute poisoning due to peritoneal lavage with mercury bichloride.19 Acute mercury-induced pulmonary damage typically resolves completely. However, there have been reported cases of exposure progressing to interstitial emphysema, pneumatocele, pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, interstitial fibrosis, and chronic respiratory insufficiency, with examples of fatal acute respiratory distress syndrome being reported.5,16,20 Although individuals who inhale mercury vapors initially may be unaware of exposure due to little upper airway irritation, symptoms following an initial acute exposure may include ptyalism, a metallic taste, dysphagia, enteritis, diarrhea, nausea, renal damage, and CNS effects.16 Additionally, exposure may lead to confusion with signs and symptoms of metal fume fever, including shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain, stomatitis, lethargy, and vomiting.20

Chronic exposure to mercury vapor can result in accumulation of mercury in the body, leading to neuropsychiatric, dermatologic, oropharyngeal, and renal manifestations. Sore throat, fever, headache, fatigue, dyspnea, chest pain, and pneumonitis are common.16 Typically, low-level exposure to elemental mercury does not lead to long-lasting health effects. However, individuals exposed to high-level elemental mercury vapors may require hospitalization. Treatment of acute mercury poisoning consists of removing the source of exposure, followed by cardiopulmonary support.16

Specific assays for mercury levels in blood and urine are useful to assess the level of exposure and risk to the patient. Blood mercury concentrations of 20 µg/L or below are considered within reference range; however, once blood and urine concentrations of mercury exceed 100 µg/L, clinical signs of acute mercury poisoning typically manifest.21 Chest radiographs can reveal pulmonary damage, while complete blood cell count, metabolic panel, and urinalysis can assess damage to other organs. Neuropsychiatric testing and nerve conduction studies may provide objective evidence of CNS toxicity. Assays for N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase can provide an indication of early renal tubular dysfunction.16

Elemental mercury is not absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, posing minimal risk for acute toxicity from ingestion. Generally, less than 10% of ingested inorganic mercury is absorbed from the gut, while elemental mercury is nonabsorbable.10 If an individual ingests a large amount of mercury, it may persist in the gastrointestinal tract for an extended period. Mercury is radiopaque, and abdominal radiographs should be obtained in all cases of ingestion.16

Mercury is toxic to the CNS and peripheral nervous system, resulting in erethism mercurialis, a constellation of neuropsychologic signs and symptoms including restlessness, irritability, insomnia, emotional lability, difficulty concentrating, and impaired memory. In severe cases, delirium and psychosis may develop. Other CNS effects include tremors, paresthesia, dysarthria, neuromuscular changes, headaches, polyneuropathy, and cerebellar ataxia, as well as ophthalmologic and audiologic impairment.5,16

Upon inhalation exposure, patients with respiratory concerns should be given oxygen. Bronchospasms are treated with bronchodilators; however, if multiple chemical exposures are suspected, bronchial-sensitizing agents may pose additional risks. Corticosteroids and antibiotics have been recommended for treatment of chemical pneumonitis, but their efficacy has not been substantiated.16

Skin reactions associated with skin contact to elemental mercury are rare. However, hives and dermatitis have been observed following accidental contact with inorganic mercury compounds.5 Manifestation in children chronically exposed to mercury includes a nonallergic hypersensitivity (acrodynia),5,17 which is characterized by pain and dusky pink discoloration in the hands and feet, most often seen in children chronically exposed to mercury absorbed from vapor inhalation or cutaneous exposure.16

Renal conditions associated with acute inhalation of elemental mercury vapor include proteinuria, nephrotic syndrome, temporary tubular dysfunction, acute tubular necrosis, and oliguric renal failure.16 Chronic exposure to inorganic mercury compounds also has been reported to cause renal damage.5 Chelation therapy should be performed for any symptomatic patient with a clear history of acute elemental mercury exposure.16 The most frequently used chelation agent in cases of acute inorganic mercury exposures is dimercaprol. In rare cases of mercury intoxication, hemodialysis is required in the treatment of renal failure and to expedite removal of dimercaprol-mercury complexes.16

Cardiovascular symptoms associated with acute inhalation of high levels of elemental mercury include tachycardia and hypertension.16 Increases in blood pressure, palpitations, and heart rate also have been observed in instances of acute elemental mercury exposure. Studies show that exposure to mercury increases both the risk for acute myocardial infarction as well as death from coronary heart and cardiovascular diseases.5

Conclusion

Mercury poisoning presents with varied neuropsychologic signs and symptoms. Our case provides insight into a unique route of exposure for mercury toxicity. In addition to the unusual presentation of a mercury granuloma, our case illustrates how surgical techniques can aid in removal of cutaneous reservoirs in the setting of percutaneous exposure.

Evidence of human exposure to mercury dates as far back as the Egyptians in 1500

Mercury release in the environment primarily is a function of human activity, including coal-fired power plants, residential heating, and mining.9,10 Mercury from these sources is commonly found in the sediment of lakes and bays, where it is enzymatically converted to methylmercury by aquatic microorganisms; subsequent food chain biomagnification results in elevated mercury levels in apex predators. Substantial release of mercury into the environment also can be attributed to health care facilities from their use of thermometers containing 0.5 to 3 g of elemental mercury,11 blood pressure monitors, and medical waste incinerators.5

Mercury has been reported as the second most common cause of heavy metal poisoning after lead.12 Standards from the US Food and Drug Administration dictate that methylmercury levels in fish and wheat products must not exceed 1 ppm.13 Most plant and animal food sources contain methylmercury at levels between 0.0001 and 0.01 ppm; mercury concentrations are especially high in tuna, averaging 0.4 ppm, while larger predatory fish contain levels in excess of 1 ppm.14 The use of mercury-containing cosmetic products also presents a substantial exposure risk to consumers.5,10 In one study, 3.3% of skin-lightening creams and soaps purchased within the United States contained concentrations of mercury exceeding 1000 ppm.15

We describe a case of mercury toxicity resulting from intentional injection of liquid mercury into the right antecubital fossa in a suicide attempt.

Case Report

A 31-year-old woman presented to the family practice center for evaluation of a firm stained area on the skin of the right arm. She reported increasing anxiety, depression, tremors, irritability, and difficulty concentrating over the last 6 months. She denied headache and joint or muscle pain. Four years earlier, she had broken apart a thermometer and injected approximately 0.7 mL of its contents into the right arm in a suicide attempt. She intended to inject the thermometer’s contents directly into a vein, but the material instead entered the surrounding tissue. She denied notable pain or itching overlying the injection site. Her medications included aripiprazole and buspirone. She noted that she smoked half a pack of cigarettes per day and had a history of methamphetamine abuse. She was homeless and unemployed. Physical examination revealed an anxious tremulous woman with an erythematous to bluish gray, firm plaque on the right antecubital fossa (Figure 1). There were no notable tremors and no gait disturbance.

Her blood mercury level was greater than 100 µg/L and urine mercury was 477 µg/g (reference ranges, 1–8 μg/L and 4–5 μg/L, respectively). A radiograph of the right elbow area revealed scattered punctate foci of increased density within or overlying the anterolateral elbow soft tissues. She was diagnosed with mercury granuloma causing chronic mercury elevation. She underwent excision of the granuloma (Figure 2) with endovascular surgery via an elliptical incision. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Comment

Elemental mercury is a silver liquid at room temperature that spontaneously evaporates to form mercury vapor, an invisible, odorless, toxic gas. Accidental cutaneous exposure typically is safely managed by washing exposed skin with soap and water,16 though there is a potential risk for systemic absorption, especially when the skin is inflamed. When metallic mercury is subcutaneously injected, it is advised to promptly excise all subcutaneous areas containing mercury, regardless of any symptoms of systemic toxicity. Patients should subsequently be monitored for signs of both central nervous system (CNS) and renal deficits, undergo chelation therapy when systemic effects are apparent, and finally receive psychiatric consultation and treatment when necessary.17

Inorganic mercury compounds are formed when elemental mercury combines with sulfur or oxygen and often take the form of mercury salts, which appear as white crystals.16 These salts occur naturally in the environment and are used in pesticides, antiseptics, and skin-lightening creams and soaps.18

Methylmercury is a highly toxic, organic compound that is capable of crossing the placental and blood-brain barriers. It is the most common organic mercury compound found in the environment.16 Most humans have trace amounts of methylmercury in their bodies, typically as a result of consuming seafood.5

Exposure to mercury most commonly occurs through chronic consumption of methylmercury in seafood or acute inhalation of elemental mercury vapors.9 Iatrogenic cases of mercury exposure via injection also have been reported in the literature, including a case resulting in acute poisoning due to peritoneal lavage with mercury bichloride.19 Acute mercury-induced pulmonary damage typically resolves completely. However, there have been reported cases of exposure progressing to interstitial emphysema, pneumatocele, pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, interstitial fibrosis, and chronic respiratory insufficiency, with examples of fatal acute respiratory distress syndrome being reported.5,16,20 Although individuals who inhale mercury vapors initially may be unaware of exposure due to little upper airway irritation, symptoms following an initial acute exposure may include ptyalism, a metallic taste, dysphagia, enteritis, diarrhea, nausea, renal damage, and CNS effects.16 Additionally, exposure may lead to confusion with signs and symptoms of metal fume fever, including shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain, stomatitis, lethargy, and vomiting.20

Chronic exposure to mercury vapor can result in accumulation of mercury in the body, leading to neuropsychiatric, dermatologic, oropharyngeal, and renal manifestations. Sore throat, fever, headache, fatigue, dyspnea, chest pain, and pneumonitis are common.16 Typically, low-level exposure to elemental mercury does not lead to long-lasting health effects. However, individuals exposed to high-level elemental mercury vapors may require hospitalization. Treatment of acute mercury poisoning consists of removing the source of exposure, followed by cardiopulmonary support.16

Specific assays for mercury levels in blood and urine are useful to assess the level of exposure and risk to the patient. Blood mercury concentrations of 20 µg/L or below are considered within reference range; however, once blood and urine concentrations of mercury exceed 100 µg/L, clinical signs of acute mercury poisoning typically manifest.21 Chest radiographs can reveal pulmonary damage, while complete blood cell count, metabolic panel, and urinalysis can assess damage to other organs. Neuropsychiatric testing and nerve conduction studies may provide objective evidence of CNS toxicity. Assays for N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase can provide an indication of early renal tubular dysfunction.16

Elemental mercury is not absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, posing minimal risk for acute toxicity from ingestion. Generally, less than 10% of ingested inorganic mercury is absorbed from the gut, while elemental mercury is nonabsorbable.10 If an individual ingests a large amount of mercury, it may persist in the gastrointestinal tract for an extended period. Mercury is radiopaque, and abdominal radiographs should be obtained in all cases of ingestion.16

Mercury is toxic to the CNS and peripheral nervous system, resulting in erethism mercurialis, a constellation of neuropsychologic signs and symptoms including restlessness, irritability, insomnia, emotional lability, difficulty concentrating, and impaired memory. In severe cases, delirium and psychosis may develop. Other CNS effects include tremors, paresthesia, dysarthria, neuromuscular changes, headaches, polyneuropathy, and cerebellar ataxia, as well as ophthalmologic and audiologic impairment.5,16

Upon inhalation exposure, patients with respiratory concerns should be given oxygen. Bronchospasms are treated with bronchodilators; however, if multiple chemical exposures are suspected, bronchial-sensitizing agents may pose additional risks. Corticosteroids and antibiotics have been recommended for treatment of chemical pneumonitis, but their efficacy has not been substantiated.16

Skin reactions associated with skin contact to elemental mercury are rare. However, hives and dermatitis have been observed following accidental contact with inorganic mercury compounds.5 Manifestation in children chronically exposed to mercury includes a nonallergic hypersensitivity (acrodynia),5,17 which is characterized by pain and dusky pink discoloration in the hands and feet, most often seen in children chronically exposed to mercury absorbed from vapor inhalation or cutaneous exposure.16

Renal conditions associated with acute inhalation of elemental mercury vapor include proteinuria, nephrotic syndrome, temporary tubular dysfunction, acute tubular necrosis, and oliguric renal failure.16 Chronic exposure to inorganic mercury compounds also has been reported to cause renal damage.5 Chelation therapy should be performed for any symptomatic patient with a clear history of acute elemental mercury exposure.16 The most frequently used chelation agent in cases of acute inorganic mercury exposures is dimercaprol. In rare cases of mercury intoxication, hemodialysis is required in the treatment of renal failure and to expedite removal of dimercaprol-mercury complexes.16

Cardiovascular symptoms associated with acute inhalation of high levels of elemental mercury include tachycardia and hypertension.16 Increases in blood pressure, palpitations, and heart rate also have been observed in instances of acute elemental mercury exposure. Studies show that exposure to mercury increases both the risk for acute myocardial infarction as well as death from coronary heart and cardiovascular diseases.5

Conclusion

Mercury poisoning presents with varied neuropsychologic signs and symptoms. Our case provides insight into a unique route of exposure for mercury toxicity. In addition to the unusual presentation of a mercury granuloma, our case illustrates how surgical techniques can aid in removal of cutaneous reservoirs in the setting of percutaneous exposure.

- History of mercury. Government of Canada website. Modified April 26, 2010. Accessed March 11, 2021. https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/pollutants/mercury-environment/about/history.html

- Dartmouth Toxic Metals Superfund Research Program website. Accessed March 11, 2021. https://sites.dartmouth.edu/toxmetal/

- Norn S, Permin H, Kruse E, et al. Mercury—a major agent in the history of medicine and alchemy [in Danish]. Dan Medicinhist Arbog. 2008;36:21-40.

- Waldron HA. Did the Mad Hatter have mercury poisoning? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;287:1961.

- Poulin J, Gibb H. Mercury: assessing the environmental burden of disease at national and local levels. WHO Environmental Burden of Disease Series No. 16. World Health Organization; 2008.

- Charcot JM. Clinical lectures of the diseases of the nervous system. In: Kinnier Wilson SA. The Landmark Library of Neurology and Neurosurgery. Gryphon Editions; 1994:186.

- Kinnier Wilson SA. Neurology. In: Kinnier Wilson SA. The Landmark Library of Neurology and Neurosurgery. Gryphon Editions; 1994:739-740.

- Harada M. Minamata disease: methylmercury poisoning in Japan caused by environmental pollution. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1995;25:1-24.

- Mercury and health. World Health Organization website. Updated March 31, 2017. Accessed March 12, 2021. http://www.whoint/mediacentre/factsheets/fs361/en/

- Olson DA. Mercury toxicity. Updated November 5, 2018. Accessed March 12, 2021.http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1175560-overview

- Mercury thermometers. Environmental Protection Agency website. Updated June 26, 2018. https://www.epa.gov/mercury/mercury-thermometers

- Jao-Tan C, Pope E. Cutaneous poisoning syndromes in children: a review. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18:410-416.

- US Department of Health and Human Services: Public Health Service Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Toxicological profile for mercury: regulations and advisories. Published March 1999. Accessed March 23, 2021. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp46.pdf

- US Food and Drug Administration. Mercury levels in commercial fish and shellfish (1990-2012). Updated October 25, 2017. Accessed March 16, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/food/metals-and-your-food/mercury-levels-commercial-fish-and-shellfish-1990-2012

- Hamann CR, Boonchai W, Wen L, et al. Spectrometric analysis of mercury content in 549 skin-lightening products: is mercury toxicity a hidden global health hazard? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:281-287.e3.

- Mercury. Managing Hazardous Materials Incidents. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry website. Accessed March 16, 2021. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/MHMI/mmg46.pdf

- Krohn IT, Solof A, Mobini J, et al. Subcutaneous injection of metallic mercury. JAMA. 1980;243:548-549.

- Lai O, Parsi KK, Wu D, et al. Mercury toxicity presenting acrodynia and a papulovesicular eruption in a 5-year-old girl. Dermatol Online J. 2016;16;22:13030/qt6444r7nc.

- Dolianiti M, Tasiopoulou K, Kalostou A, et al. Mercury bichloride iatrogenic poisoning: a case report. J Clin Toxicol. 2016;6:2. doi:10.4172/2161-0495.1000290

- Broussard LA, Hammett-Stabler CA, Winecker RE, et al. The toxicology of mercury. Lab Med. 2002;33:614-625. doi:10.1309/5HY1-V3NE-2LFL-P9MT

- Byeong-Jin Y, Byoung-Gwon K, Man-Joong J, et al. Evaluation of mercury exposure levels, clinical diagnosis and treatment for mercury intoxication. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2016;28:5.

- History of mercury. Government of Canada website. Modified April 26, 2010. Accessed March 11, 2021. https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/pollutants/mercury-environment/about/history.html

- Dartmouth Toxic Metals Superfund Research Program website. Accessed March 11, 2021. https://sites.dartmouth.edu/toxmetal/

- Norn S, Permin H, Kruse E, et al. Mercury—a major agent in the history of medicine and alchemy [in Danish]. Dan Medicinhist Arbog. 2008;36:21-40.

- Waldron HA. Did the Mad Hatter have mercury poisoning? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;287:1961.

- Poulin J, Gibb H. Mercury: assessing the environmental burden of disease at national and local levels. WHO Environmental Burden of Disease Series No. 16. World Health Organization; 2008.

- Charcot JM. Clinical lectures of the diseases of the nervous system. In: Kinnier Wilson SA. The Landmark Library of Neurology and Neurosurgery. Gryphon Editions; 1994:186.

- Kinnier Wilson SA. Neurology. In: Kinnier Wilson SA. The Landmark Library of Neurology and Neurosurgery. Gryphon Editions; 1994:739-740.

- Harada M. Minamata disease: methylmercury poisoning in Japan caused by environmental pollution. Crit Rev Toxicol. 1995;25:1-24.

- Mercury and health. World Health Organization website. Updated March 31, 2017. Accessed March 12, 2021. http://www.whoint/mediacentre/factsheets/fs361/en/

- Olson DA. Mercury toxicity. Updated November 5, 2018. Accessed March 12, 2021.http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1175560-overview

- Mercury thermometers. Environmental Protection Agency website. Updated June 26, 2018. https://www.epa.gov/mercury/mercury-thermometers

- Jao-Tan C, Pope E. Cutaneous poisoning syndromes in children: a review. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18:410-416.

- US Department of Health and Human Services: Public Health Service Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Toxicological profile for mercury: regulations and advisories. Published March 1999. Accessed March 23, 2021. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp46.pdf

- US Food and Drug Administration. Mercury levels in commercial fish and shellfish (1990-2012). Updated October 25, 2017. Accessed March 16, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/food/metals-and-your-food/mercury-levels-commercial-fish-and-shellfish-1990-2012

- Hamann CR, Boonchai W, Wen L, et al. Spectrometric analysis of mercury content in 549 skin-lightening products: is mercury toxicity a hidden global health hazard? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:281-287.e3.

- Mercury. Managing Hazardous Materials Incidents. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry website. Accessed March 16, 2021. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/MHMI/mmg46.pdf

- Krohn IT, Solof A, Mobini J, et al. Subcutaneous injection of metallic mercury. JAMA. 1980;243:548-549.

- Lai O, Parsi KK, Wu D, et al. Mercury toxicity presenting acrodynia and a papulovesicular eruption in a 5-year-old girl. Dermatol Online J. 2016;16;22:13030/qt6444r7nc.

- Dolianiti M, Tasiopoulou K, Kalostou A, et al. Mercury bichloride iatrogenic poisoning: a case report. J Clin Toxicol. 2016;6:2. doi:10.4172/2161-0495.1000290

- Broussard LA, Hammett-Stabler CA, Winecker RE, et al. The toxicology of mercury. Lab Med. 2002;33:614-625. doi:10.1309/5HY1-V3NE-2LFL-P9MT

- Byeong-Jin Y, Byoung-Gwon K, Man-Joong J, et al. Evaluation of mercury exposure levels, clinical diagnosis and treatment for mercury intoxication. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2016;28:5.

Practice Points

- Chronic mercury granulomas can present as firm, erythematous to bluish gray plaques.

- Accidental skin contact to elemental mercury may cause urticaria and dermatitis.

- Blood mercury concentrations below 20 11µg/L are considered within reference range; once blood and urine concentrations exceed 100 11µg/L, clinical signs of acute mercury poisoning typically manifest.

- Mercury is toxic to the central and peripheral nervous systems, resulting in erethism mercurialis, a constellation of neuropsychologic signs and symptoms including restlessness, irritability, insomnia, emotional lability, difficulty concentrating, and impaired memory.